Preterm birth, 90% of which occurs between 32 and <37 weeks’ gestation,1 2 is a complex heterogeneous syndrome interlinked with the stillbirth and intrauterine growth restriction syndromes.3 4 Its phenotypes are associated with different gains in neonatal weight,5 morbidity and mortality,6 and perhaps body composition, growth and development. Preterm birth is related to several aetiologies, although nearly 30% of all preterm births are not associated with any maternal/pregnancy conditions or fetal growth restriction.6 This group is, therefore, the target population for constructing postnatal growth standards for preterm infants.7 8 There is disagreement, however, about how best to monitor the postnatal growth of such a heterogeneous group of newborns. In fact, a systematic review identified 61 existing longitudinal charts for preterm infants, many with considerable limitations in gestational age estimation, body measurement, length of follow-up and description of feeding practices and morbidities.9

The problem requires four fundamental issues to be considered.10

First, size at birth measures (eg, birth weight, length and head circumference), which are taken only once per infant, are a retrospective summary of fetal growth reflecting the intrauterine environment and overall efficiency of placental nutrient transfer. Postnatal growth, on the other hand, requires repeated anthropometric measures after birth, complemented by feeding practices and morbidity data. Therefore, the use of size at birth by gestational age, cross-sectional data taken only at birth to evaluate the postnatal growth of preterm infants cannot be justified either physiologically or clinically. Implicit in the concept of growth is the requirement for repeated measures over time, which can obviously not be captured with a single birth measure. Furthermore, fundamental factors determining the postnatal growth of preterm infants that change over time, such as feeding regimens and organ maturity influencing morbidity, are by definition not included in the data used to construct cross-sectional size at birth charts. Hence, calling such charts ‘postnatal growth references’ should be avoided because the terminology misrepresents the nature of the underlying data used for their construction.

Moreover, using newborn cross-sectional data, in an attempt to reconstruct uncomplicated fetal growth patterns retrospectively, and then pretending that those patterns represent the normative postnatal growth for preterm infants is a massive biological jump that requires accepting the concept that preterm infants should grow like fetuses.11 This often-cited concept has not been proven empirically. Fetal growth trajectories are seldom achieved in clinical practice resulting in ‘extra-uterine growth restriction’ being overdiagnosed.12 In addition, the metabolic mechanisms are not equivalent as early fetal growth is mostly related to IGF-2 and its effect on placental size and nutrient delivery,13 while postnatal growth is modulated primarily by the GH/IGR-1 axis.

Feeding regimens for preterm infants that aim to reach ‘fetal growth’ levels (ie, very rapid weight gain during the first few months of life), and that result in both a transient high proportion of body fat by term-corrected age14 and possibly an early childhood adiposity rebound,15 could do more harm than good.16 Such preterm infants may be accumulating long-term, adverse, health effects, including the appearance in adulthood of components of the metabolic syndrome, and increased cardiovascular risk.17 18 Thus, given the limited information available in the literature, it would seem important to implement large, multicentre, randomised trials as a matter of urgency to evaluate feeding strategies for both very preterm and moderate to late preterm infants; the latter group is a rather neglected subpopulation even though it represents close to 80% of all preterms.19

Second, size at birth reference charts are mostly based on routinely collected data, with limited or no standardisation or quality control of anthropometric measures or reliable gestational age estimation, and describe how fetuses have grown at a particular place and time (even decades ago). Conversely, preterm postnatal standard charts, with prospective measures standardised, gestational age estimated by early ultrasound and childhood follow-up, define how preterm infants should grow under optimal conditions considering their degree of maturation.8 20 The terms ‘reference’ and ‘standard’ should not be used interchangeably because they are based on different data and have different objectives.

Third, ‘distance growth’,21 which represents the value attained at specific postnatal ages, is the most robust and commonly used tool in clinical practice. Velocity growth expresses the change in value of an anthropometric measure taken on the same infant between two time periods,22 that is, it requires individual,23 24 repeated data.8 20 Hence, the need for more than one measure across time on the same individual is germane to the growth velocity concept.22 Cross-sectional size at birth data, by definition, cannot estimate velocity growth.

In some clinical settings for practical reasons, velocity fixed rates of 15 g/kg/day, 10–30 g/day for weight or 1 cm/week for length are used. This is problematic because the 15 g/kg/day constant weight gain value is neither biologically plausible nor supported by longitudinal data. An alternative is to evaluate weight gain as g/kg/day25 at different postnatal ages. However, this format provides a misleading picture of newborn growth kinetics by describing an earlier peak of weight gain that has limited contribution to the total weight increase.5 26 The weight velocity of these tiny babies, if it is going to be used, is better described as weight changes in g/day according to postnatal age, which follows a non-linear pattern.5 26 Considering the methodological issues, difficulties with calculation, interpretation at the bedside and that most units routinely just plot anthropometric measures according to age, distance charts are preferable to velocity growth measures.

Lastly, postnatal charts for preterm infants should include weight, length and head circumference taken from the same newborn population. This is a problem for size at birth charts derived from combining studies.11 For example, only two27 28 of the six data sets included in an often employed meta-analysis29 had all three measures taken from the same infant. Therefore, when these charts are used to evaluate a newborn, its weight is compared with one population but its length and head circumference (very relevant for developmental risk) are compared with a different population.

Considering these conceptual issues, the INTERGROWTH-21st Project has produced international standards for the postnatal growth of preterm infants that complement the existing WHO Child Growth Standards, which are only for term newborns. We enrolled, for the first time, ‘healthy’ pregnant women initiating care <14 weeks’ gestation to study, in the same sample, fetal growth,30 newborn size,31 and body composition,32 the postnatal growth of preterm newborns,8 and the follow-up of all these babies up to 2 years of age,33 including neurodevelopmental assessment.34 The project used the same equipment, standardised methodology and feeding practices based on human milk, to produce the first integrated set of international standards for monitoring fetal and newborn growth and development. Detailed descriptions of breast feeding patterns and the introduction of complementary feeding are presented elsewhere.35 The project matches the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study because it adopted the same prescriptive approach in selecting pregnant women at population and individual levels,36 and because the newborn anthropometry overlaps with the WHO Child Growth Standards perfectly.37 38 Exactly the same prescriptive approach was applied to construct7 the longitudinal INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards.8

Finding that healthy pregnant women receiving adequate healthcare can achieve a preterm birth rate as low as 4.9% has established an evidence-based target for perinatal programmes. However, it meant that fewer preterms were born than originally estimated, mostly because of the reduction of very preterm births.8 10 Hence, the international INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards are robust standards from >32 to 64 weeks’ postmenstrual age for >90% of the preterm babies born worldwide. They provide, even at low gestational ages, consistent smooth centiles that follow a logical pattern,8 based on repeated measures directly relevant to how preterm infants should grow. Supporting e-learning courses for the global standardisation of growth monitoring of preterm infants are freely available at: https://globalhealthtrainingcentre.tghn.org/intergrowth-21st-course-maternal-fetal-and-newborn-growth-monitoring/ https://globalhealthtrainingcentre.tghn.org/preterm-infant-feeding-and-growth-monitoring-implementation-intergrowth-21st-protocol/.

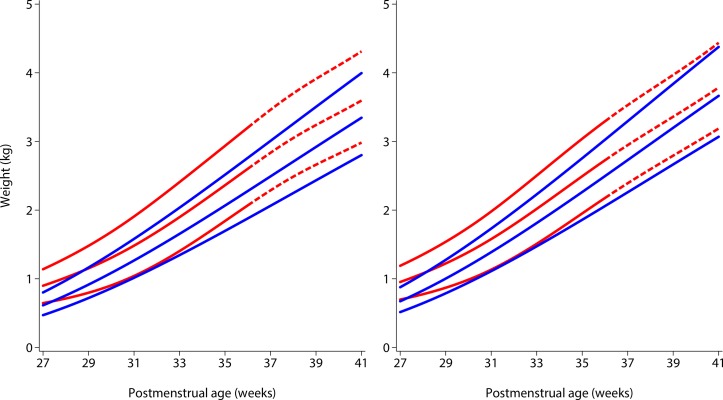

Which type of chart is selected for growth monitoring has a profound effect on the clinical care of all preterm infants. Figure 1 compares the international INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards8 for weight with the Fenton size at birth charts (the latter developed using cross-sectional birth data from studies of newborns without postnatal follow-up) at the 10th, 50th and 90th centiles from 27 to 40 weeks29; a longer and detailed comparison is discussed elsewhere.10

Figure 1.

Comparison of 10th, 50th and 90th centiles of the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards for weight8 (solid blue lines) with the Fenton size at birth charts26 (solid and dashed red lines) according to sex (left, girls; right, boys) from 27+0 to 40+6 postmenstrual weeks. The dashed red lines correspond to the gestational ages at which the Fenton charts were modelled to reach the WHO Child Growth Standards at 50 weeks (figure modified from Villar et al 10).

Despite similar slopes, size at birth charts are consistently higher than the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Standards up to term, that is, preterm infants’ growth is not that of fetuses, which is reflected by Fenton charts. Very reassuringly, the INTERGROWTH-21st centiles have smooth patterns consistent with the remainder of the follow-up period. This is because the centiles in the INTERGROWTH-21st standards are based on 1759 repeated measures (equivalent to a cross-sectional study with double the sample size) taken across the follow-up period up to 64 weeks,8 not just the values at 27 weeks.

These differences have major clinical implications: (1) size at birth charts diagnose more ‘extra-uterine growth restricted preterms’, many of whom are healthy and growing adequately along their centile, yet they now require ‘treatments’ and nutritional support, and (2) if it is expected that preterm infants should reach fetal weight levels, as required by size at birth charts, they must be fed more than the recommended human milk-based strategy because presently they seldom reach such weights. This strategy forces preterm infants to weight and body composition levels disproportionate to their length, that is, they become overweight for length at discharge, which increases the risk for chronic diseases,17 18 but may not improve developmental outcomes.39 Is this the goal for preterm infants at the time of the global obesity epidemic? We do not believe so: the global prevention of obesity, cardiometabolic syndrome and related complications in preterm infants should start at the incubator.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support provided by Drs A Lambert, E Staines-Urias and EO Ohuma.

Footnotes

Contributors: JV and SHK conceptualised and designed the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. FB, EB, FG and ZAB supervised and coordinated the project’s overall undertaking. JV, SHK, JFA and ZAB wrote the report with input from all coauthors. All coauthors read the report and made suggestions on its content.

Funding: This work was supported by the INTERGROWTH-21st grant 49038 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the University of Oxford and by the Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation.

Disclaimer: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Family Larsson- Rosenquist Foundation had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Women participating in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project gave written consent

Ethics approval: Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee ’C' (reference: 08/H0606/139)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Goldenberg RL, Gravett MG, Iams J, et al. . The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:113–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer MS, Papageorghiou A, Culhane J, et al. . Challenges in defining and classifying the preterm birth syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:108–12. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hirst JE, Villar J, Victora CG, et al. . International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st). The antepartum stillbirth syndrome: risk factors and pregnancy conditions identified from the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG 2018;125:1145–53. 10.1111/1471-0528.14463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Victora CG, Villar J, Barros FC, et al. . Anthropometric Characterization of Impaired Fetal Growth: Risk Factors for and Prognosis of Newborns With Stunting or Wasting. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:e151431 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bertino E, Coscia A, Mombrò M, et al. . Postnatal weight increase and growth velocity of very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91:F349–56. 10.1136/adc.2005.090993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barros FC, Papageorghiou AT, Victora CG, et al. . The distribution of clinical phenotypes of preterm birth syndrome: implications for prevention. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:220–9. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Villar J, Knight HE, de Onis M, et al. . Conceptual issues related to the construction of prescriptive standards for the evaluation of postnatal growth of preterm infants. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:1034–8. 10.1136/adc.2009.175067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Villar J, Giuliani F, Bhutta ZA, et al. . Postnatal growth standards for preterm infants: the Preterm Postnatal Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e681–91. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00163-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giuliani F, Cheikh Ismail L, Bertino E, et al. . Monitoring postnatal growth of preterm infants: present and future. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:635S–47. 10.3945/ajcn.114.106310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Villar J, Giuliani F, Barros F, et al. . Monitoring the postnatal growth of preterm infants: a paradigm change. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172467 10.1542/peds.2017-2467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pereira-da-Silva L, Virella D. Is intrauterine growth appropriate to monitor postnatal growth of preterm neonates? BMC Pediatr 2014;14:14 10.1186/1471-2431-14-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tuzun F, Yucesoy E, Baysal B, et al. . Comparison of INTERGROWTH-21 and Fenton growth standards to assess size at birth and extrauterine growth in very preterm infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:2252–7. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1339270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kadakia R, Josefson J. The Relationship of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 to Fetal Growth and Adiposity. Horm Res Paediatr 2016;85:75–82. 10.1159/000443500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang P, Zhou J, Yin Y, et al. . Effects of breast-feeding compared with formula-feeding on preterm infant body composition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2016;116:132–41. 10.1017/S0007114516001720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koyama S, Ichikawa G, Kojima M, et al. . Adiposity rebound and the development of metabolic syndrome. Pediatrics 2014;133:e114–19. 10.1542/peds.2013-0966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cole TJ, Statnikov Y, Santhakumaran S, et al. . Birth weight and longitudinal growth in infants born below 32 weeks' gestation: a UK population study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014;99:F34–40. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parkinson JR, Hyde MJ, Gale C, et al. . Preterm birth and the metabolic syndrome in adult life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1240–63. 10.1542/peds.2012-2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morrison KM, Ramsingh L, Gunn E, et al. . Cardiometabolic Health in Adults Born Premature With Extremely Low Birth Weight. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20160515 10.1542/peds.2016-0515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harding JE, Cormack BE, Alexander T, et al. . Advances in nutrition of the newborn infant. Lancet 2017;389:1660–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30552-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, et al. . WHO Child Growth Standards. Acta Paediatr Suppl 2006;450:1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gasser T, Kneip A, Binding A, et al. . The dynamics of linear growth in distance, velocity and acceleration. Ann Hum Biol 1991;18:187–205. 10.1080/03014469100001522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Onis M, Siyam A, Borghi E, et al. . Comparison of the World Health Organization growth velocity standards with existing US reference data. Pediatrics 2011;128:e18–26. 10.1542/peds.2010-2630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pauls J, Bauer K, Versmold H. Postnatal body weight curves for infants below 1000 g birth weight receiving early enteral and parenteral nutrition. Eur J Pediatr 1998;157:416–21. 10.1007/s004310050842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ehrenkranz RA, Younes N, Lemons JA, et al. . Longitudinal growth of hospitalized very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 1999;104(2 Pt 1):280–9. 10.1542/peds.104.2.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fenton TR, Anderson D, Groh-Wargo S, et al. . An Attempt to Standardize the Calculation of Growth Velocity of Preterm Infants-Evaluation of Practical Bedside Methods. J Pediatr 2018;196:77–83. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bertino E, Coscia A, Boni L, et al. . Weight growth velocity of very low birth weight infants: role of gender, gestational age and major morbidities. Early Hum Dev 2009;85:339–47. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, et al. . New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics 2010;125:e214–24. 10.1542/peds.2009-0913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bertino E, Spada E, Occhi L, et al. . Neonatal anthropometric charts: the Italian neonatal study compared with other European studies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;51:353–361. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181da213e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:59 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papageorghiou AT, Ohuma EO, Altman DG, et al. . International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 2014;384:869–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61490-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villar J, Cheikh Ismail L, Victora CG, et al. . International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 2014;384:857–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Villar J, Puglia FA, Fenton TR, et al. . Body composition at birth and its relationship with neonatal anthropometric ratios: the newborn body composition study of the INTERGROWTH-21st project. Pediatr Res 2017;82:305–16. 10.1038/pr.2017.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Villar J, Cheikh Ismail L, Staines Urias E, et al. . The satisfactory growth and development at 2 years of age of the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards cohort support its appropriateness for constructing international standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:S841–S854.e2. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fernandes M, Stein A, Newton CR, et al. . The INTERGROWTH-21st Project Neurodevelopment Package: a novel method for the multi-dimensional assessment of neurodevelopment in pre-school age children. PLoS One 2014;9:e113360 10.1371/journal.pone.0113360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cheikh Ismail L, Giuliani F, Bhat BA, et al. . Preterm feeding recommendations are achievable in large-scale research studies. BMC Nutr 2016;2:9 10.1186/s40795-016-0047-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Villar J, Altman DG, Purwar M, et al. . The objectives, design and implementation of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG 2013;120(Suppl 2):9–26. 10.1111/1471-0528.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Villar J, Papageorghiou AT, Pang R, et al. . The likeness of fetal growth and newborn size across non-isolated populations in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study and Newborn Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:781–92. 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70121-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Villar J, Papageorghiou AT, Pang R, et al. . Monitoring human growth and development: a continuum from the womb to the classroom. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:494–9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Horta BL, Victora CG, de Mola CL, et al. . Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain in early life with human capital at 30 years of age. J Pediatr 2017;182:85–91. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]