Abstract

Previously, we demonstrated that intratumoral delivery of adenoviral vector encoding single-chain (sc)IL-23 (Ad.scIL-23) was able to induce systemic antitumor immunity. Here, we examined the role of IL-23 in diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Intravenous delivery of Ad.scIL-23 did not accelerate the onset of hyperglycemia but instead resulted in the development of psoriatic arthritis. Ad.scIL-23–treated mice developed erythema, scales, and thickening of the skin, as well as intervertebral disc degeneration and extensive synovial hypertrophy and loss of articular cartilage in the knees. Immunological analysis revealed activation of conventional T helper type 17 cells and IL-17–producing γδ T cells along with a significant depletion and suppression of T cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes. Furthermore, treatment with anti–IL-17 antibody reduced joint and skin psoriatic arthritis pathologies. Thus, these Ad.scIL-23–treated mice represent a physiologically relevant model of psoriatic arthritis for understanding disease progression and for testing therapeutic approaches.—Flores, R. R., Carbo, L., Kim, E., Van Meter, M., De Padilla, C. M. L., Zhao, J., Colangelo, D., Yousefzadeh, M. J., Angelini, L. A., Zhang, L., Pola, E., Vo, N., Evans, C. H., Gambotto, A., Niedernhofer, L. J., Robbins, P. D. Adenoviral gene transfer of a single-chain IL-23 induces psoriatic arthritis–like symptoms in NOD mice.

Keywords: psoriasis, type 1 diabetes, interleukin-23, adenovirus, interleukin-17

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease of the skin that exists in 3% of the world population. Psoriasis vulgaris, or plaque psoriasis, which manifests as raised itchy erythematous plaques in the skin, is the most common form of psoriasis and accounts for nearly 70% of the patients with psoriasis (1). Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is the second most common form of psoriasis and is found in ∼30% of patients with psoriasis (1). Patients with PsA have inflammation and autoimmunity occurring in the spine, the peripheral joints, and the site of attachment of ligament to the bone, as well as skin plaques (2). Patients with psoriasis are also prone to develop metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease.

Symptoms of psoriasis in humans include patches of red, inflamed skin with involved areas of the skin developing lesions, referred to as Koebner’s phenomenon. During the early development of psoriatic skin lesions, dermal changes include the formation of twisted dilated vessels along with papillar edema and an infiltrate mainly consisting of dendritic cells and macrophages (3, 4). Within the fully developed lesion, there is extensive thickening of the epidermis (acanthosis) with elongated epidermal rete ridges and dermal papillae with dilated capillaries. The epidermal layer also undergoes extensive hyperplasia, which leads to thickening of stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis), whereas the stratum granulosum decreases. This increase in the number of cells on the surface of the skin leads to thick, silvery scales, another hallmark of the disease.

PsA is a chronic arthritic disease, ranging in severity from occasional flare-ups to continuous inflammation that can cause joint damage if not treated. PsA typically affects the large joints, especially those of the lower extremities and distal joints of the fingers. PsA also can affect the spine, leading to degeneration of intervertebral discs and the sacroiliac joints of the pelvis. Epidemiologic data show that in 60% of the cases, psoriatic skin lesions precede joint disease (2).

IL-23, a member of the IL-12 cytokine family, is a potent proinflammatory cytokine produced by activated dendritic cells and macrophages. Cytokines in this family exist as heterodimers, and currently there are 4 known members: IL-12, IL-23, IL-27, and IL-35 (5). IL-23 is composed of the IL-12p40 subunit, which it shares with IL-12 and its own subunit, IL-23p19. IL-23 is known to stimulate immune responses and to drive differentiation of CD4+ cells into T helper (Th) type 17 cells. Although the role that IL-12 plays in type 1 diabetes (T1D) has been examined extensively (6–9), the role of IL-23 in diabetes, either directly or indirectly through induction of Th17 cells, is contradictory, depending on the conditions in which Th17 cells are generated. Several studies suggest Th17 cells play a significant role in the etiology of T1D, whereas others suggest Th17 cells are not involved (10–13). However, when Th17 cells do contribute to the etiology of T1D, it appears to rely on cells that can simultaneously produce IL-17 and IFN-γ (13–16). This current study was initially performed to examine whether increasing the expression of IL-23 by adenoviral gene transfer exacerbated or accelerated the establishment and progression of T1D in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. Surprisingly, prediabetic NOD mice injected with adenoviral vector encoding single-chain (sc)IL-23 (Ad.scIL-23) didn’t have accelerated onset of hyperglycemia. Instead, the treated mice developed visible symptoms of psoriasis, and histological analysis demonstrated the skin pathology of the classic features of psoriasis. Importantly, mice treated with Ad.scIL-23 also exhibited signs of psoriatic arthritis with evidence of intervertebral disc degeneration and synovial hyperplasia and erosion of the cartilage of the knee. Treatment with an anti–IL-17 antibody clearly implicated IL-17 in driving pathologies associated with psoriatic arthritis in joints, discs, and skin. These results demonstrated that systemic expression of scIL-23 in NOD mice is sufficient to drive not only psoriasis but also psoriatic arthritis. In addition, this novel mouse model of psoriatic arthritis can be used for analysis of disease progression and testing of novel therapeutics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse models

Eight-week-old NOD ShijL mice (female) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were maintained under pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility at The Scripps Research Institute (Jupiter, Florida). All procedures performed were approved by The Scripps Research Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Adenovirus

Adenoviruses expressing an sc version of IL-23 has been previously described in Reay et al. (17). The scIL-23 cDNA was codon-optimized for expression in mammalian cells using the UpGene codon optimization algorithm (18) and synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, China). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Viruses were propagated on Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells and purified by CsCl banding, followed by dialysis in 3% sucrose solution. Particle titer of purified viruses and multiplicity of infection were determined as previously described in Bilbao et al. (19). Viruses were divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C until use. The expression of scIL-23 from Ad.scIL-23–infected cells was verified by ELISA.

Diabetes study

Eight-week-old NOD mice were infected once with control virus Ad.psi5 (empty vector) or with Ad.scIL-23 (5 × 1010 viral particles per mouse). Viruses were administered through intravenous injection in a total volume of 100 μl sterile saline solution. Blood glucose was tested weekly on restrained, unanesthetized mice through tail-vein bleeds using a FreeStyle Lite glucometer and test strips (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA).

Assessment of skin inflammation

The severity of skin inflammation was scored by adopting for mice the clinical Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) used to diagnose patients, with the exception being that the entire mouse was evaluated as opposed to individual plaques in humans (20). Mice were scored every 2–3 d after intravenous injection with virus for the following parameters of skin inflammation: 1) erythema, 2) scales, and 3) thickness (0, none; 1, slight; 2, moderate; 3, marked; 4, very marked or severe), resulting in a total cumulative score (20). These mice were tracked for 4 wk, at which point the mice were euthanized and tissues harvested and analyzed.

Histology

Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% formalin for at least 24 h, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed following standard procedures on paraffin-embedded tissues, which were cut into 5-μm sections. Knee and disc specimens were stained with Safranin O–Fast Green (SOFG) dye to visualize proteoglycans. Prior to initiating the staining process, specimens containing bone were decalcified. To initiate the SOFG staining, embedded tissues were deparaffinized and rehydrated with distilled water. Next, the slides were stained with hematoxylin solution for 5 min and washed with tap water for 5 min. Slides were quickly destained with acid alcohol (1% hydrochloric acid in 70% ethanol). After washing with tap water twice for 1 min, the slides were stained with Fast Green dye for 5 min. The slides were quickly rinsed with 1% acetic acid solution for 10–15 s. The slides were then stained with 0.1% Safranin O solution for 5 min. Prior to mounting the slides with resinous medium, slides were dehydrated and cleared by sequential immersion in 95% ethanol, absolute ethanol, and xylene twice for 2 min.

Immunohistochemistry

Intervertebral discs embedded in paraffin blocks were cut into 5-µm sections and were baked for an hour prior to staining. To reduce background signals, which result from various chemical modifications, deparaffinized slides underwent an antigen-retrieval procedure to offset backgrounds as a result of such modifications. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked using a 10% normal serum with 1% bovine serum albumin in 1× PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Afterwards, anti-aggrecan primary antibody (1:200 dilution; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) was added and incubated at 10°C overnight. Slides were washed (Tris-buffered saline plus 0.025% Triton X-100) prior to incubation with enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit; Tris-buffered saline with 1% bovine serum albumin) for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were washed and chromogen substrate was added for 10 min at room temperature. Afterward, the slides were rinsed with deionized with H2O and counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min. The slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted with a cover slip.

Intervertebral disc glycosaminoglycan and PicoGreen DNA assay

The intervertebral discs from mice were dissected and the nucleus pulposus (NP) was isolated from the core of the disc using locking forceps under a dissecting microscope (21). After dissection, digestion buffer [50 mM sodium acetate, 5 mM EDTA (pH 7.15), 5 mM l-cystine, 300 μg/ml papain, 55 mM citric acid, and 150 mM sodium chloride] was added to dilute the samples at a 1:10 ratio, and the mixture was incubated at 60°C for 2 h. Afterward, the samples were centrifuged for 30 min at maximum speed and 40 μl of the supernatant was added to 200 μl of dimethyl-methylene blue dye per well in duplicates in a clear 96-well plate (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) with chondroitin 6 sulfate (C-8529; MilliporeSigma) used as a standard. To quantitate the DNA content, each sample was initially diluted (1:20) in 1× Tris-EDTA buffer; 100 μl of diluted sample was transferred to a black 96-well plate (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). An equal volume of PicoGreen (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) solution was then added, mixed well, and the fluorescence of each sample was measured using a Multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) using the following settings: excitation, 485 nm; and emission, 538 nm.

Flow cytometric analysis of spleen and lymph nodes

The spleens (SPLs) and lymph nodes (LNs) were converted into single-cell suspensions and washed with sterile PBS. Red blood cells were depleted with red blood cell lysis buffer (150 mM ammonium chloride, 1 mM sodium bicarbonate, and 0.1 mM EDTA at pH 7.7), and the cells were extensively washed before being passed through a cell strainer. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell-sorter buffer (2% fetal bovine serum, 1× PBS, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.04% sodium azide) at 3.75 × 106 cells/ml. A 200-μl aliquot of each sample was transferred into 96-well polypropylene round-bottom plates (BD Biosciences). FcRs were blocked using anti-CD16/CD32 mAb (1:600 dilution; purchased from BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 10°C. The cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAb (purchased from BD Bioscience or Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at the appropriate titer for 45 min at 10°C. The cells were washed with fluorescence-activated cell-sorter buffer twice and fixed using 2% paraformaldehyde. For intracellular staining, the cells were processed using a cytofix-cytoperm buffer kit purchased from BD Biosciences and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were processed on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

RNA extraction from skin

A small piece of flash-frozen skin (50–150 mg) was placed in a mortar and ground with a pestle in liquid nitrogen until a fine powder formed. The powder was then transferred into a homogenization tube, into which 1 ml of Trizol solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added. The powder was processed using an MP FastPrep instrument (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) set at 6 m/s for 30 s. The homogenate was centrifuged at Vmax for 5 min to pellet the cellular debris. The cleared mixture was transferred into a fresh autoclaved tube, into which 200 μl of chloroform was added and mixed thoroughly. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 min. The samples were then centrifuged at Vmax for 15 min at 4°C. The aqueous layer was pipetted into a fresh microcentrifuge tube. To the aqueous layer 1 ml of isopropyl alcohol was added and thoroughly mixed. The mixture was centrifuged at Vmax at 4°C for 15 min. The isopropyl alcohol was decanted, leaving the small white pellet undisturbed. To the pellet, 1 ml of ice-cold 75% ethanol was added, mixed, and then centrifuged at Vmax for 15 min at 4°C. The ethanol was decanted and the pellet air dried. The extracted RNA was resuspended with 50 μl of water. Extraction of RNA from splenocytes was performed similarly; however, SPLs were converted into a single-cell suspension by mechanical disruption. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions on an Thermo Fisher Scientific StepOnePlus instrument. Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Table 1 (Supplemental Data). Relative expression of each gene was normalized to β-actin from samples derived from Ad.psi5-infected mice.

TABLE 1.

List of RT-PCR primers

| Gene | Primer sequences, 5′–3′ |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| IL-17A | ATCCCTCAAAGCTCAGCGTGTC | GGGTCTTCATTGCGGTGGAGAG |

| IL-22 | ATACATCGTCAACCGCACCTTT | AGCCGGACATCTGTGTTGTTAT |

| IL-6 | CTGATGCTGGTGACAACCAC | AGCCTCCGACTTGTGAAGTG |

| IL-23 | AGCAACTTCACACCTCCCTAC | ACTGCTGACTAGAACTCAGGC |

| TNF-α | TCAAGGACTCAAATGGGCTTTC | TGCAGAACTCAGGAATGGACAT |

| CCR6 | TCCAGGCAACCAAATCTTTC | GATGAACCACACTGCCACAC |

| IL-20 | TTTTAAGGACGACTGAGTCTTTGA | ACCCTGTCCAGATAGAATCTCACTA |

Primers for IFN-γ (PPM03121A) and β-actin (PPM02945B) were purchased from Qiagen (Germantown, MD, USA).

ELISA

Serum concentrations of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) were measured for mouse MCP-1–specific ELISA (Raybiotech, Peachtree Corners, GA, USA). Twenty microliters of serum, obtained at the time of euthanasia, was used for ELISA per manufacturer’s specifications, and absorbance was quantified at 450 nm using a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All standards and samples were measured in duplicate.

Anti–IL-17 antibody treatment

Mice were infected with Ad.scIL-23 virus as previously described. Two days following infection, mice were injected with either isotype-control antibody or with anti-mouse IL-17 A/F monoclonal antibody (100 μg/mouse/injection; IgG2a isotype; Thermo Fisher Scientific) through intraperitoneal injection. The mice were dosed with antibody weekly for up to 3 wk. As previously described, the mice were evaluated and scored using PASI every 2–3 d. At the completion of the experiment, tissues were harvested, and serum was collected and analyzed.

RESULTS

Ad.scIL-23 treatment of NOD mice suppresses the development of diabetes

To determine if IL-23 played a role in the pathogenesis of T1D, 8-wk-old prediabetic NOD mice were injected intravenously with Ad.scIL-23 or control Ad.psi5 virus, and the development of hyperglycemia was monitored. Surprisingly, systemic expression of scIL-23 did not accelerate the rate of onset of diabetes in NOD mice when compared with control mice (Fig. 1A). Instead, although most of the control mice became diabetic by 24 wk, the majority of Ad.scIL-23–treated NOD mice did not develop diabetes until 32 wk. To examine the effect of scIL-23 expression on immune infiltration in the pancreas, 4 wk following the infection with Ad.scIL-23, the islets from these 12-wk-old mice with normal glycemia were scored for insulitis. As shown in Fig. 1B, β-islets from NOD mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 exhibited lower insulitis and contained more healthy islets when compared with control mice.

Figure 1.

NOD mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 experience a significant delay in the development of diabetes and reduction of insulitis. A) Eight-week-old NOD mice were injected once with Ad.psi5 or with Ad.scIL-23 virus through tail-vein injection. Blood glucose was assessed every week. Mice were considered diabetic with 2 consecutive daily readings ≥250 mg/dl. Arrow indicates age of mice at injection with virus. B) Pancreases were fixed in 10% formalin for at least 24 h, and H&E staining was done following standard procedures on paraffin-embedded tissues, which were cut into 5-μm sections. For control mice, 188 islets were scored for insulitis and 170 islets were scored for Ad.scIL-23 mice (1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test; ***P < 0.001). The results shown are from 1 experiment (control mice, n = 17; Ad.scIL-23 mice, n = 8) (A); 2 cumulative independent experiments (10 mice per experiment) are also shown (B).

Ad.scIL-23–treated NOD mice exhibit symptoms of psoriasis

Interestingly, treatment of NOD mice with Ad.scIL-23 did not accelerate the rate of hyperglycemia onset but instead resulted in the mice having a poor coat condition and a scruffy appearance (Fig. 2A, B). The coats of these mice exhibited significant hair loss, particularly in the thoracic trunk area. Furthermore, the ears, tails, and feet of Ad.scIL-23–treated mice exhibited signs of erythema, scaling, and thickening, which are associated with psoriasis (Fig. 2B). The mice also developed increased dorsal kyphosis, indicative of spinal disc degeneration or arthritis. All these symptoms are consistent with psoriasis-like disease. Thus, the Ad.scIL-23–infected mice were scored for symptoms of psoriasis by adopting the PASI. PASI is used in the clinical setting, which was applied here to score the entire mouse, as opposed to patients where plaques are scored individually (20). Mice were scored for erythema (Fig. 2C), scales (Fig. 2D), and skin thickness (Fig. 2E), from which a cumulative score was calculated (Fig. 2F). Ad.scIL-23–infected NOD mice rapidly developed erythema and thickening of the skin, which was evident within 7 d of infection. Scales took more time to develop but were apparent within 10 d on the ears and more so on the tails. The total cumulative score showed that the psoriatic symptoms plateaued between 3 and 4 wk following infection (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

NOD mice treated with Ad.scIL-23 exhibit signs of psoriasis. A, B) Mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 displayed differences in appearance when compared with Ad.psi5 mice, particularly 1) the ears, 2) spine, 3) tail, and 4) feet. C–F) Two days following the injection of virus, and every 2–3 d thereafter, mice were tracked for inflammation by assessing the skin for erythema (C), scales (D), and thickness (E), from which a cumulative score was calculated (F). The depths of these symptoms were scored using the following scale: 0 = none, 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, 3 = marked, 4 = very marked or severe. These mice were tracked for 4 wk. Results shown are cumulative of 2 independent experiments (control, n = 15 mice; Ad.scIL-23, n = 15 mice; experiment 1, n = 10; experiment 2, n = 5).

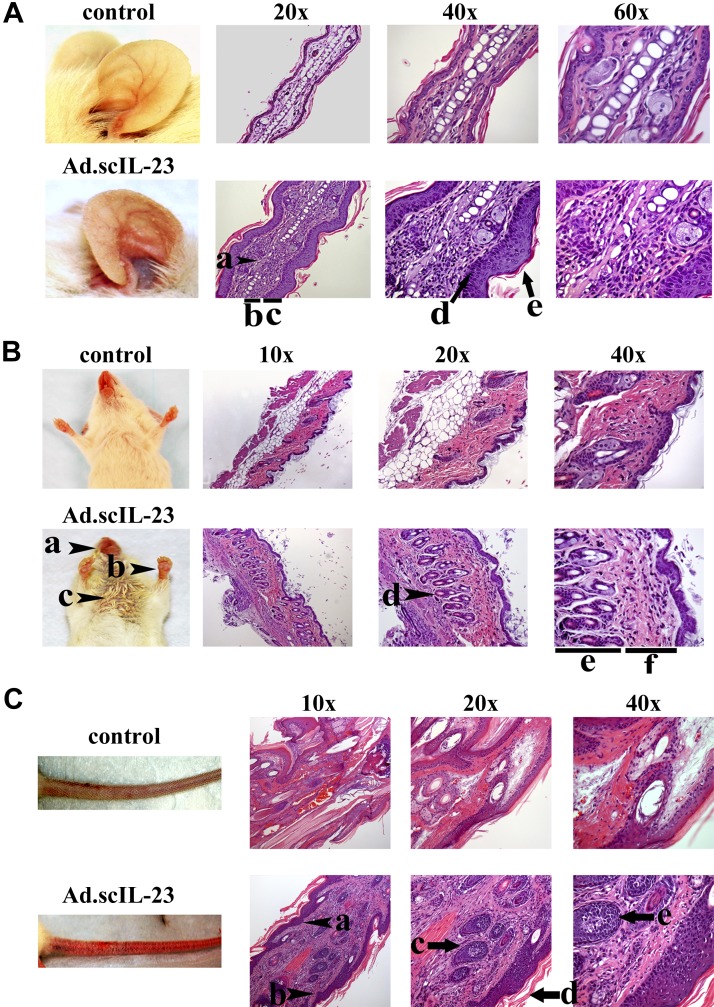

Ad.scIL-23–infected mice develop extensive skin inflammation

In NOD mice infected with Ad.scIL-23, there was a marked thickening of the ear, to the extent that the ears become less translucent and the veins less visible when compared with control mice (Fig. 3A). The ears also gained a reddish scaly appearance. Histological analysis revealed a loss of cartilage and structural integrity of the collagen scaffolding in the center of the ear, and keratinocytes were seen occupying these spaces (Fig. 3A, arrowhead a). Furthermore, Masson’s trichrome staining of the ear showed extensive deposition of keratin in the outer epidermal layer (Supplemental Fig. S1; top 2 panels). The ears also showed marked thickening of both the epidermal and the dermal layers (Fig. 3A, bars b and c). At a higher magnification, parakeratosis was evident along the base of the epidermis (Fig. 3A, arrow d), and extensive hyperkeratosis (Fig. 3A, arrow e) was evident in the ears of Ad.scIL-23–infected mice. Inflammation was not restricted to the ear, because erythema was apparent in the muzzle, paws, and torso of infected mice (Fig. 3B, arrowheads a–c). Furthermore, significant hair loss was seen (Fig. 3B, arrowhead c). Histological analysis of the skin from the torso showed significant loss of fat cells (Fig. 3B; clearly evident at magnification 10×; control vs. Ad.scIL-23 mice) to the extent that Ad.scIL-23–infected mice experienced a significant decrease in body weight, which occurred 3 wk following infection of virus (Supplemental Fig. S2). Like the ear, keratinocyte hyperplasia led to a significant increase in the thickness of the dermal layer between the hair follicle and epidermis (Fig. 3B, all magnifications). The hair follicles appeared inflamed (Fig. 3B, arrow d) and, at higher magnifications, the thickness of the hair follicle and the surrounding dermis were significantly increased (Fig. 3B, bars e and f). Masson’s trichrome staining confirmed the accumulation of collagen and keratin in the outer layer of the epidermis and within the base of the hair follicles (Supplemental Fig. S1; bottom 2 panels). Further analysis of mice treated with Ad.scIL-23 showed that these mice developed a scaly inflamed appearance and exhibited a high degree of erythema on their tails (Fig. 3C). Histological analysis showed a significant increase in hyperplasia in both the dermal and epidermal layers (Fig. 3C, bottom panels, all magnifications). Furrows in the epidermis also extended into the dermal layer, similar to epidermal retes often seen in patients with psoriasis (Fig. 3C, arrowheads a and b). H&E staining also showed inflammation of tendons (Fig. 3C, arrows c and e) within the tails and hyperkeratosis (Fig. 3C, arrow d) outside the tails in these mice.

Figure 3.

Histological analysis of the ears (A), skin (B), and tail (C) of NOD mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 reveals characteristics of psoriasis. A) Loss of cartilage (a); thickening of the dermal (b) and epidermal (c) layers; and keratosis (d) of the epidermis. B) Erythyma of the muzzle (a), paws (b), and torso (c); significant hair loss also indicated by c; and increased thickening of the dermal (e) and epidermal (f) layers. C) Epidermal retes (a, b); inflamed tendons (c, e); and hyperkeratosis (d) outside the tail. Tissue specimens were collected 4 wk following infection and fixed in 10% formalin for at least 4 h, which was followed by incubation in 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight. H&E staining was done following standard procedures on paraffin-embedded tissues, which were cut into 5-μm sections. The results shown are representative of 2 independent experiments (control, n = 15 mice; Ad.scIL-23 n = 15 mice; experiment 1, n = 10; experiment 2, n = 5).

Intervertebral disc degeneration in Ad.scIL-23–infected mice

As previously shown in Fig. 2, mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 appeared to be hunched, indicative of kyphosis or spinal degeneration. Histological analysis of spines from mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 showed an increased deterioration of the intervertebral disc in both the annulus fibrosus and of the nucleus pulposus (NP) (Fig. 4A). To confirm disc degeneration, the NP proteoglycan proteins of these mice were extracted and measured by glycosaminoglycan assay. There was a significant loss of proteoglycan in the discs from Ad.scIL-23–treated mice (Fig. 4B). To further confirm these results, the level of aggrecan, a major proteoglycan and an integral component of the extracellular matrix of cartilaginous tissues (22), was examined by immunohistochemistry. There was considerably less aggrecan present in the NP of mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 (Fig. 4C). In addition, the annulus fibrosus, which surrounds the central pulposus, was disorganized in comparison with the control spinal disc. Also, the matrix in the annulus fibrosus appeared compact, flattened, and disorganized.

Figure 4.

Histological analysis reveals damage to the NP in the spinal discs of NOD mice treated with Ad.scIL-23. A, C) Spines were collected 4 wk following infection, decalcified, embedded in paraffin, and sagittally sliced into 5-μm sections for H&E (A) and aggregan (C) immunohistochemistry staining using standard procedures. The asterisk indicates the NP, whereas the arrow indicates the annulus fibrosus. B) NP tissues were isolated by microdissection using a dissection microscope from 5 lumbar discs of each mouse, pooled and digested with papain at 60°C for 2 h. The DNA concentration of each sample was measured using the PicoGreen assay and used to normalize the glycosaminoglycan values (control, n = 5; Ad.scIL-23, n = 5; Unpaired t test; *P < 0.05). The results shown in C are from 2 independent experiments (control, n = 5 mice; Ad.scIL-23, n = 5 mice; experiment 1, n = 3; experiment 2, n = 2).

Joint degeneration in Ad.scIL-23–infected mice

The knee joints from Ad.scIL-23–infected mice were also analyzed histologically. In the knee joints from Ad.scIL-23–treated mice, there was considerable erosion of cartilage (red staining in SOFG panel) and, in some instances, the presence of fibrotic tissue within the joint space when compared with control mice (Fig. 5). There also was a variable degree of synovitis and synovial thickening (Fig. 5B, D). As indicated by SOFG staining, there was extensive deterioration of the articular cartilage lining of the knee joint (Fig. 5D). In addition, the red arrow indicates loss of proteoglycan in mice infected with Ad.scIL-23, whereas the black arrow indicates a full-thickness cartilage lesion (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, H&E staining shows neovascularization and extensive proliferation in the synovium from knee joints from Ad.scIL-23–infected mice (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of Ad.scIL-23 on the knee joints of NOD mice. Decalcified sections were stained with H&E (A, B) or SOFG (C, D). Knee joints of animals receiving Ad.scIL-23 (bottom panels) showed synovial hypertrophy accompanied by neovascularization and loss of articular cartilage from both tibial and femoral surfaces. D) Red arrow indicates loss of proteoglycan and the black arrow indicates thickness of cartilage lesion. The results shown are representative of 2 independent experiments (both control and Ad.scIL-23, n = 5 mice; experiment 1, n = 2; experiment 2, n = 3).

Induction of Th17 cells in the SPL and depletion of T cells in the pancreatic LN following Ad.scIL-23

IL-23 plays a role in the differentiation of Th17 cells and the induction of IL-17 expression through transcription factors like signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and Retineic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor gamma (ROR-γt) (23–25). To determine the impact that scIL-23 had on the differentiation of T cells in NOD mice, which typically develop a destructive Th1 response (26, 27), the SPLs, peripheral skin-draining lymph nodes (LN) (pLNs; axillary and inguinal LNs), and pancreatic LNs (panLNs) were collected and analyzed 4 wk following infection. We gated on CD3+ cells and then crossgated on CD4+ and CD8+ cells, revealing 3 major subsets (CD4+CD8−, CD4−CD8−, and CD4−CD8+). Splenic CD4−CD8− T cells from Ad.scIL-23–infected mice produced significantly more IFN-γ than control. However, no differences were observed with CD4+CD8− (Supplemental Fig. S5A) or CD8+CD4− subsets (unpublished results), which was similar to the pattern observed for IL-17. In addition, analysis of the pLN showed no differences for either cytokine (Supplemental Fig. S5B). In contrast, a significant decrease in the frequency of both IFN-γ and IL-17 positive cells (Supplemental Fig. S5C) was detected in panLNs, suggesting suppression of the anti–β-islet response in NOD mice, consistent with the delayed onset of hyperglycemia. Interestingly, quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that treatment with Ad.scIL-23 resulted in an increase in the expression of endogenous IL-23 at 4 wk posttreatment in the SPL (Supplemental Fig. S3). There was also a significant increase in the expression of the IL-10 cytokine family member IL-22 in the SPL and skin. Although no IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, TGF-β, and IL-6 were detected in the serum (unpublished results), the treated mice did show elevated levels of MCP-1 and CCL2 (C-C ligand 2) (Supplemental Fig. S4A).

There also were no differences in the expression of activation markers (CD25, PD-1, CD127, and CD44) in either the CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell subsets (Supplemental Fig. S6A, B) between control and treated mice. However, the overall frequency of activated T cells in the pLN of infected mice was greater than control, consistent with a sustained immune response in the skin. In addition, there was a decrease in the frequency of activated T cells in the panLN of Ad.scIL-23 mice, suggesting depletion of the anti–β-islet T cells (Supplemental Fig. S6C).

Anti–IL-17 mAb treatment reduces psoriatic symptoms in Ad.scIL-23–infected mice

To determine if the psoriatic symptoms displayed in mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 were driven through the IL-23–Th17–IL-17 axis, infected mice were treated with anti–IL-17 mAb. Mice received weekly injections of anti–IL-17 mAb or the isotype control beginning a few days after infection with virus. Tracking these mice for clinical features of psoriasis revealed that mice treated with anti–IL-17 mAb had less erythema and thickening of the skin and a lowered cumulative score, although the scales remained unchanged (Fig. 6A). The apparent lack of an effect of anti–IL-17 mAb treatment on the formation of scales may reflect the function of other Th17 cytokines such as IL-22, TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, or scIL-23 itself (28–31). There was also a significant reduction in the hyperplasia or thickening of the epidermal layers in the ear and skin, whereas there was no difference in the tail (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, analysis of the knee joints showed inhibiting IL-17 reduced arthritic symptoms [Fig. 6C (H&E) 8D (SOFG)]. H&E staining (Fig. 6C) revealed reduced skin thickness (short black arrows) and reduced synovial hyperplasia (thin blue arrows) in mice treated with anti–IL-17. Additionally, SOFG staining (Fig. 6D) revealed retention of articular cartilage in mice treated with anti–IL-17. The arrows identify a large cartilagenous lesion in the knee joint of a control animals (Fig. 6D, right panel) that is absent from an animal treated with anti–IL-17 (Fig. 6D, left panel). We also analyzed the serum from these mice, which showed a systemic reduction of the inflammatory response, as evident by reduced levels of MCP-1 (Supplemental Fig. S4B). These results demonstrated that IL-17 plays an important role in driving psoriatic arthritis downstream of IL-23.

Figure 6.

Anti–IL-17 mAb treatment reduces psoriatic symptoms in Ad.scIL-23–infected mice. Eight-week-old mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 were treated with either anti–IL-17 mAb on a weekly basis for up to 3 wk, isotype-control Ab, or left alone. A) Mice were monitored for symptoms of psoriasis utilizing the PASI system (2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). B) Epidermal thickening was determined by measuring the length of the layer from top to bottom as shown in the representative image and reported for the ear, torso skin, and tail in micrometers (unpaired Student’s t test; ****P < 0.0001). C, D) Histological comparison of knee joints from mice treated with anti–IL-17 mAb or control Ab is shown. H&E staining (C) showed reduced skin thickness (short black arrows) and reduced synovial hyperplasia (thin blue arrows) in mice treated with anti–IL-17. SOFG staining (D) reveals retention of articular cartilage in mice treated with anti–IL-17. The arrows identify a large cartilagenous lesion in the knee joint of control animals (right panel) that is absent from animals treated with anti–IL-17 (left panel). The results shown in this figure are from 1 experiment. For both control and Ad.scIL-23, n = 6 mice per group for all tissues analyzed.

DISCUSSION

The IL-12 family of heterodimeric cytokines, consisting of IL-12, IL-23, IL-27, and IL-35, plays important roles in regulating the immune response. IL-12 family members are composed of a heterodimer consisting of the following α and β chains: IL-12 (p40 and p35), IL-23 (p40 and p19), IL-27 [Epstein-Barr virus induced gene 3 (Ebi3) and p28], and IL-35 (Ebi3 and p35) (5). We have examined both the role that members of the IL-12 cytokine family play in health and disease and their utilization as therapeutic agents (17, 32, 33). Previously, we demonstrated that adenoviral-mediated, intratumoral delivery of a cDNA encoding an scIL-23 (Ad.scIL-23) was able to induce systemic antitumor immunity in mouse models (17). In contrast, an adenoviral vector expressing a novel IL-12 family member, termed IL-Y (p40 and p28), an sc molecule, was immunosuppressive, inhibiting the antitumor response as well as delaying the onset of diabetes in NOD mice (34). Here, we examined whether IL-23 plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of T1D, possibly through induction of Th17 cells in NOD mice.

Surprisingly, NOD mice infected with Ad.scIL-23 did not have accelerated onset of hyperglycemia and instead developed symptoms of psoriatic arthritis. NOD mice treated with Ad.scIL-23 have classic features of psoriasis including erythema, scales, and thickening of the skin. The mice also exhibited signs of psoriatic arthritis, as evidenced by degeneration and inflammation in the intervertebral discs and knee joints. In addition, a significant increase in both conventional Th17 cells (Fig. 6) in the SPL were detected. Although there was a preferential activation of IL-17+ T cells, IL-23 did not simply induce activation of T cells across all subsets tested or in all tissues analyzed. Consistent with the observed activation of IL-17+ T cells, we demonstrated a key role for IL-17 in driving psoriatic arthritis downstream of IL-23 using an anti–IL-17 antibody. The depletion and suppression of diabetogenic T cells appears to be specific toward IL-17+ T cells. In fact, the reduction and suppression of diabetogenic T cells in the panLN was a consistent observation in our analysis. We observed not only depletion of T cells but also suppression of IFN-γ and IL-17 in the panLN. Previously, IL-23 was shown to inhibit the development of Th1 responses by antagonizing the effects of IL-12 (35), and this inhibition was most apparent in T cells with an activated and memory phenotype. It also possible that scIL-23 induced exhaustion in diabetogenic T cells (36). Taken together, these results suggest that transient, systemic overexpression of a scIL-23 is sufficient to alter the immune response to reduce the progression of diabetes and induce the development of an IL-17–driven psoriasis with associated psoriatic arthritis–like pathologies.

This key role for IL-23 in driving murine psoriatic arthritis is consistent with clinical results in humans where antibodies targeting the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23 have therapeutic effects. In addition, antibodies against human p40 blocked the spread of psoriasis in a xenotransplant mouse model (37). Furthermore, IL-23 has been implicated in disease pathogenesis by the identification of IL-23R, IL-12 (p40), and IL-23 (p19) as psoriasis susceptibility loci (38).

Currently, there is no murine model of psoriasis that mirrors the human disease, although some murine models develop a psoriasis-like skin disease. These include spontaneous mouse models, such as the Scd1ab-Sc1ab, proliferative dermatitis mutation Scharpincpdm-Scharpincpdm, and the flaky-skin Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7 (Ttc7fsn-Ttc7fsn) mice, among others (39–44), which have histological features of psoriasis but without apparent T-cell infiltrate. A variety of knockout (45, 46), conditional knockout (47, 48), or transgenic models (49–51), including many with inflammatory cytokines and even certain transcription factors expressed in the epidermis from a K14 or K5 promoter, mimic certain aspects of diseases. For example, conditional knockout of Inhibitor of NF-kB kinase subunit beta (IKK-β) and Inhibitor of NF-kB kappa (IkB-α) in the epidermis results in inflammation with some features of psoriasis, serving to identify specific factors that could be involved in human disease (47, 48). In addition, expression of a constitutively active form of STAT3 from the K5 promoter, K5.Stat3C, resulted in psoriasis-like disease. STAT3 is highly expressed and active in human plaque lesions (52). Interestingly, grafting of skin from K5.Stat3C-transgenic mice onto athymic nude mice was not sufficient to induce lesions in grafted skin following wounding. Here, the adoptive transfer of T cells in addition to the skin graft from K5.Stat3.3C mice was required for the induction of psoriatic lesion following wounding. In addition to these transgenic and transplant models, s.c. injections of certain recombinant factors like IL-21 (53) and, in particular, IL-23, results in induction of a psoriasis-like disease in the skin (54–57). Interestingly, overexpression of the p40 subunit of IL-23 in the skin induced some pathologies associated with psoriasis (58, 59) and antibodies targeting p40 have shown clinical efficacy (60, 61). However, although these mouse models develop certain pathologies similar to human disease, none develop psoriatic arthritis with disc and joint pathology. In addition, each of these models is missing or defective in one or more hallmarks of human diseases such as hyperkeratosis, defective keratinocyte differentiation, increases in epidermal T cells and neutrophils, and intradermal microabscesses.

Our mouse model of psoriatic arthritis reflects many aspects of human disease, including the most prominent feature being the pathological thickening of the skin, a common but important feature of mouse models of psoriasis. Consistent with patients with psoriasis, there is extensive thickening of the epidermis (acanthosis) in skin samples from our mice, which in patients is the result of excessive proliferation of keratinocytes. Furthermore, we observed thickening of the stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis) in skin samples from the torso and ear. Also, there was retention of nuclei in the stratum corneum (parakeratosis) in the skin samples. An additional similarity with human disease is the detection of psoriasis-associated cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17 in T cells from the SPL (Fig. 6). This is consistent with data derived from patients in which transcripts for IL-17 (62), along with IL-23 (63), were detected in plaque lesions. Furthermore, xenotransplant studies have shown CD4+ T cells play a crucial role in disease because nonlesioned skin from patients with psoriasis engrafted onto SCID mice develop psoriatic lesions following spontaneous activation of donor CD4+ T cells or following intradermal injection of CD4+ T cells (64, 65). Evidence for roles for IL-17 and Th17 cells in psoriasis was also suggested by a study in which neutralizing antibodies to IL-17 blocks the development of psoriasis in the K5.Stat3C transgenic mouse model (28).

Our mouse model also exhibits clinical features of psoriatic arthritis. PsA in humans is characterized by inflammation of the peripheral joints and enthesis, dactylitis, synovial hyperplasia, cartilage destruction, and intervertebral disc deterioration (66, 67). In the NOD Ad.scIL-23–treated mice, there also was synovial proliferation with extensive loss of cartilage and marked neovascularization of the synovium of knee joints with synovial hyperplasia. Furthermore, we detected evidence of axial arthritis with degeneration of the intervertebral discs of Ad.scIL-23–infected mice with a loss of proteoglycans, including aggrecan, from the NP.

In summary, we have described the development of a mouse model of psoriatic arthritis that encompasses most of the clinical features of the human disease. These results demonstrate that increased systemic levels of IL-23 drive not only plaque psoriasis but psoriatic arthritis as well. Furthermore, our data show that the potent proinflammatory cytokine IL-23 doesn’t accelerate the onset of hyperglycemia in these T1D-susceptible mice. Thus, these mice represent a physiologically relevant model of psoriatic arthritis for understanding disease progress and testing therapeutic approaches.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Biviana Torres (The Scripps Research Institute) for her assistance with flow cytometry and Shannon Howard, Sara McGowan, and Tokio Sano (all from The Scripps Research Institute) for their assistance in collecting and the processing of tissues. The authors acknowledge and extend gratitude to Yuan Yuan Ling (retired, formerly of The Scripps Research Institute) for years of service to science. This work was supported by Grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging (AG024827, AG044376), NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR051456), and a program grant from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation to P.D.R. R.R.F. was supported by a T32 grant from NIH on Autoimmunity and Immunopathology. This project used the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Vector Facilities (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) supported by the University of Pittsburgh’s NIH Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA047904. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Ad.scIL-23

adenoviral vector encoding single-chain IL-23

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- K5.Stat3C

STAT3 from the K5 promoter

- LN

lymph node

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- NOD

nonobese diabetic

- NP

nucleus pulposus

- panLN

pancreatic LN

- PASI

Psoriasis Area Severity Index

- pLN

peripheral skin-draining lymph node

- PsA

psoriatic arthritis

- sc

single chain

- SOFG

Safranin O–Fast Green

- SPL

spleen

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- Th

T helper

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R. R. Flores designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; L. Carbo, E. Kim, M. Van Meter, C. M. L. De Padilla, J. Zhao, D. Colangelo, and M. J. Yousefzadeh helped to performed experiments; and E. Pola, N. Vo, C. H. Evans, A. Gambotto, L. J. Niedernhofer, and P. D. Robbins help to design experiments and write and edit the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schön M. P., Boehncke W. H. (2005) Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 1899–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baraliakos X., Coates L. C., Braun J. (2012) The involvement of the spine in psoriatic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 39, 418–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng Y., Chang C., Lu Q. (2016) The inflammatory response in psoriasis: a comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 50, 377–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowes M. A., Suárez-Fariñas M., Krueger J. G. (2014) Immunology of psoriasis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 227–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vignali D. A., Kuchroo V. K. (2012) IL-12 family cytokines: immunological playmakers. Nat. Immunol. 13, 722–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nitta Y., Kawamoto S., Tashiro F., Aihara H., Yoshimoto T., Nariuchi H., Tabayashi K., Miyazaki J. (2001) IL-12 plays a pathologic role at the inflammatory loci in the development of diabetes in NOD mice. J. Autoimmun. 16, 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson P. B., Mistry M. S., Maki R. A., Yang W., Schwarz D. A., Johnson E. B., Lio F. M., Alleva D. G. (2003) Cuttine edge: diabetes-associated quantitative trait locus, Idd4, is responsible for the IL-12p40 overexpression defect in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. J. Immunol. 171, 3333–3337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trembleau S., Penna G., Gregori S., Giarratana N., Adorini L. (2003) IL-12 administration accelerates autoimmune diabetes in both wild-type and IFN-gamma-deficient nonobese diabetic mice, revealing pathogenic and protective effects of IL-12-induced IFN-gamma. J. Immunol. 170, 5491–5501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alleva D. G., Pavlovich R. P., Grant C., Kaser S. B., Beller D. I. (2000) Aberrant macrophage cytokine production is a conserved feature among autoimmune-prone mouse strains: elevated interleukin (IL)-12 and an imbalance in tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IL-10 define a unique cytokine profile in macrophages from young nonobese diabetic mice. Diabetes 49, 1106–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar P., Subramaniyam G. (2015) Molecular underpinnings of Th17 immune-regulation and their implications in autoimmune diabetes. Cytokine 71, 366–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellemore S. M., Nikoopour E., Schwartz J. A., Krougly O., Lee-Chan E., Singh B. (2015) Preventative role of interleukin-17 producing regulatory T helper type 17 (Treg 17) cells in type 1 diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 182, 261–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellemore S. M., Nikoopour E., Krougly O., Lee-Chan E., Fouser L. A., Singh B. (2016) Pathogenic T helper type 17 cells contribute to type 1 diabetes independently of interleukin-22. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 183, 380–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker L. S., von Herrath M. (2016) CD4 T cell differentiation in type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 183, 16–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirota K., Duarte J. H., Veldhoen M., Hornsby E., Li Y., Cua D. J., Ahlfors H., Wilhelm C., Tolaini M., Menzel U., Garefalaki A., Potocnik A. J., Stockinger B. (2011) Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 255–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honkanen J., Nieminen J. K., Gao R., Luopajarvi K., Salo H. M., Ilonen J., Knip M., Otonkoski T., Vaarala O. (2010) IL-17 immunity in human type 1 diabetes. J. Immunol. 185, 1959–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinert-Hartwall L., Honkanen J., Salo H. M., Nieminen J. K., Luopajärvi K., Härkönen T., Veijola R., Simell O., Ilonen J., Peet A., Tillmann V., Knip M., Vaarala O.; DIABIMMUNE Study Group (2015) Th1/Th17 plasticity is a marker of advanced β cell autoimmunity and impaired glucose tolerance in humans. J. Immunol. 194, 68–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reay J., Gambotto A., Robbins P. D. (2012) The antitumor effects of adenoviral-mediated, intratumoral delivery of interleukin 23 require endogenous IL-12. Cancer Gene Ther. 19, 135–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao W., Rzewski A., Sun H., Robbins P. D., Gambotto A. (2004) UpGene: application of a web-based DNA codon optimization algorithm. Biotechnol. Prog. 20, 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilbao R., Reay D. P., Hughes T., Biermann V., Volpers C., Goldberg L., Bergelson J., Kochanek S., Clemens P. R. (2003) Fetal muscle gene transfer is not enhanced by an RGD capsid modification to high-capacity adenoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 10, 1821–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oji V., Luger T. A. (2015) The skin in psoriasis: assessment and challenges. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 33 (Suppl 93), S14–S19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vo N., Seo H. Y., Robinson A., Sowa G., Bentley D., Taylor L., Studer R., Usas A., Huard J., Alber S., Watkins S. C., Lee J., Coehlo P., Wang D., Loppini M., Robbins P. D., Niedernhofer L. J., Kang J. (2010) Accelerated aging of intervertebral discs in a mouse model of progeria. J. Orthop. Res. 28, 1600–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiani C., Chen L., Wu Y. J., Yee A. J., Yang B. B. (2002) Structure and function of aggrecan. Cell Res. 12, 19–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal S., Ghilardi N., Xie M. H., de Sauvage F. J., Gurney A. L. (2003) Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1910–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho M. L., Kang J. W., Moon Y. M., Nam H. J., Jhun J. Y., Heo S. B., Jin H. T., Min S. Y., Ju J. H., Park K. S., Cho Y. G., Yoon C. H., Park S. H., Sung Y. C., Kim H. Y. (2006) STAT3 and NF-kappaB signal pathway is required for IL-23-mediated IL-17 production in spontaneous arthritis animal model IL-1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 176, 5652–5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivanov I. I., McKenzie B. S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C. E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J. J., Cua D. J., Littman D. R. (2006) The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arif S., Tree T. I., Astill T. P., Tremble J. M., Bishop A. J., Dayan C. M., Roep B. O., Peakman M. (2004) Autoreactive T cell responses show proinflammatory polarization in diabetes but a regulatory phenotype in health. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 451–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz J. D., Benoist C., Mathis D. (1995) T helper cell subsets in insulin-dependent diabetes. Science 268, 1185–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakajima K., Kanda T., Takaishi M., Shiga T., Miyoshi K., Nakajima H., Kamijima R., Tarutani M., Benson J. M., Elloso M. M., Gutshall L. L., Naso M. F., Iwakura Y., DiGiovanni J., Sano S. (2011) Distinct roles of IL-23 and IL-17 in the development of psoriasis-like lesions in a mouse model. J. Immunol. 186, 4481–4489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizzo H. L., Kagami S., Phillips K. G., Kurtz S. E., Jacques S. L., Blauvelt A. (2011) IL-23-mediated psoriasis-like epidermal hyperplasia is dependent on IL-17A. J. Immunol. 186, 1495–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitra A., Raychaudhuri S. K., Raychaudhuri S. P. (2012) Functional role of IL-22 in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14, R65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Y., Danilenko D. M., Valdez P., Kasman I., Eastham-Anderson J., Wu J., Ouyang W. (2007) Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature 445, 648–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gambotto A., Tüting T., McVey D. L., Kovesdi I., Tahara H., Lotze M. T., Robbins P. D. (1999) Induction of antitumor immunity by direct intratumoral injection of a recombinant adenovirus vector expressing interleukin-12. Cancer Gene Ther. 6, 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reay J., Kim S. H., Lockhart E., Kolls J., Robbins P. D. (2009) Adenoviral-mediated, intratumor gene transfer of interleukin 23 induces a therapeutic antitumor response. Cancer Gene Ther. 16, 776–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flores R. R., Kim E., Zhou L., Yang C., Zhao J., Gambotto A., Robbins P. D. (2015) IL-Y, a synthetic member of the IL-12 cytokine family, suppresses the development of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 45, 3114–3125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieve A. N., Meeks K. D., Lee S., Berg R. E. (2010) A novel immunoregulatory function for IL-23: inhibition of IL-12-dependent IFN-γ production. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 2236–2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wherry E. J., Kurachi M. (2015) Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 486–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tonel G., Conrad C., Laggner U., Di Meglio P., Grys K., McClanahan T. K., Blumenschein W. M., Qin J. Z., Xin H., Oldham E., Kastelein R., Nickoloff B. J., Nestle F. O. (2010) Cutting edge: a critical functional role for IL-23 in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 185, 5688–5691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hüffmeier U., Lascorz J., Böhm B., Lohmann J., Wendler J., Mössner R., Reich K., Traupe H., Kurrat W., Burkhardt H., Reis A. (2009) Genetic variants of the IL-23R pathway: association with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis vulgaris, but no specific risk factor for arthritis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atochina O., Harn D. (2006) Prevention of psoriasis-like lesions development in fsn/fsn mice by helminth glycans. Exp. Dermatol. 15, 461–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beamer W. G., Pelsue S. C., Shultz L. D., Sundberg J. P., Barker J. E. (1995) The flaky skin (fsn) mutation in mice: map location and description of the anemia. Blood 86, 3220–3226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gates A. H., Karasek M. (1965) Hereditary absence of sebaceous glands in the mouse. Science 148, 1471–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundberg J. P., Beamer W. G., Shultz L. D., Dunstan R. W. (1990) Inherited mouse mutations as models of human adnexal, cornification, and papulosquamous dermatoses. J. Invest. Dermatol. 95, 625–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sundberg J. P., Dunstan R. W., Roop D. R., Beamer W. G. (1994) Full-thickness skin grafts from flaky skin mice to nude mice: maintenance of the psoriasiform phenotype. J. Invest. Dermatol. 102, 781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sundberg J. P., France M., Boggess D., Sundberg B. A., Jenson A. B., Beamer W. G., Shultz L. D. (1997) Development and progression of psoriasiform dermatitis and systemic lesions in the flaky skin (fsn) mouse mutant. Pathobiology 65, 271–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hida S., Ogasawara K., Sato K., Abe M., Takayanagi H., Yokochi T., Sato T., Hirose S., Shirai T., Taki S., Taniguchi T. (2000) CD8(+) T cell-mediated skin disease in mice lacking IRF-2, the transcriptional attenuator of interferon-alpha/beta signaling. Immunity 13, 643–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shepherd J., Little M. C., Nicklin M. J. (2004) Psoriasis-like cutaneous inflammation in mice lacking interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. J. Invest. Dermatol. 122, 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pasparakis M., Courtois G., Hafner M., Schmidt-Supprian M., Nenci A., Toksoy A., Krampert M., Goebeler M., Gillitzer R., Israel A., Krieg T., Rajewsky K., Haase I. (2002) TNF-mediated inflammatory skin disease in mice with epidermis-specific deletion of IKK2. Nature 417, 861–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stratis A., Pasparakis M., Rupec R. A., Markur D., Hartmann K., Scharffetter-Kochanek K., Peters T., van Rooijen N., Krieg T., Haase I. (2006) Pathogenic role for skin macrophages in a mouse model of keratinocyte-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2094–2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groves R. W., Mizutani H., Kieffer J. D., Kupper T. S. (1995) Inflammatory skin disease in transgenic mice that express high levels of interleukin 1 alpha in basal epidermis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11874–11878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li A. G., Wang D., Feng X. H., Wang X. J. (2004) Latent TGFbeta1 overexpression in keratinocytes results in a severe psoriasis-like skin disorder. EMBO J. 23, 1770–1781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Y. P., Li B., Hylton D., Detmar M., Yancopoulos G. D., Rudge J. S. (2003) Transgenic delivery of VEGF to mouse skin leads to an inflammatory condition resembling human psoriasis. Blood 102, 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sano S., Chan K. S., Carbajal S., Clifford J., Peavey M., Kiguchi K., Itami S., Nickoloff B. J., DiGiovanni J. (2005) Stat3 links activated keratinocytes and immunocytes required for development of psoriasis in a novel transgenic mouse model. Nat. Med. 11, 43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caruso R., Botti E., Sarra M., Esposito M., Stolfi C., Diluvio L., Giustizieri M. L., Pacciani V., Mazzotta A., Campione E., Macdonald T. T., Chimenti S., Pallone F., Costanzo A., Monteleone G. (2009) Involvement of interleukin-21 in the epidermal hyperplasia of psoriasis. Nat. Med. 15, 1013–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mabuchi T., Singh T. P., Takekoshi T., Jia G. F., Wu X., Kao M. C., Weiss I., Farber J. M., Hwang S. T. (2013) CCR6 is required for epidermal trafficking of γδ-T cells in an IL-23-induced model of psoriasiform dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suárez-Fariñas M., Arbeit R., Jiang W., Ortenzio F. S., Sullivan T., Krueger J. G. (2013) Suppression of molecular inflammatory pathways by Toll-like receptor 7, 8, and 9 antagonists in a model of IL-23-induced skin inflammation. PLoS One 8, e84634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedrick M. N., Lonsdorf A. S., Shirakawa A. K., Richard Lee C. C., Liao F., Singh S. P., Zhang H. H., Grinberg A., Love P. E., Hwang S. T., Farber J. M. (2009) CCR6 is required for IL-23-induced psoriasis-like inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2317–2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chan J. R., Blumenschein W., Murphy E., Diveu C., Wiekowski M., Abbondanzo S., Lucian L., Geissler R., Brodie S., Kimball A. B., Gorman D. M., Smith K., de Waal Malefyt R., Kastelein R. A., McClanahan T. K., Bowman E. P. (2006) IL-23 stimulates epidermal hyperplasia via TNF and IL-20R2-dependent mechanisms with implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2577–2587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kopp T., Lenz P., Bello-Fernandez C., Kastelein R. A., Kupper T. S., Stingl G. (2003) IL-23 production by cosecretion of endogenous p19 and transgenic p40 in keratin 14/p40 transgenic mice: evidence for enhanced cutaneous immunity. J. Immunol. 170, 5438–5444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kopp T., Kieffer J. D., Rot A., Strommer S., Stingl G., Kupper T. S. (2001) Inflammatory skin disease in K14/p40 transgenic mice: evidence for interleukin-12-like activities of p40. J. Invest. Dermatol. 117, 618–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griffiths C. E., Strober B. E., van de Kerkhof P., Ho V., Fidelus-Gort R., Yeilding N., Guzzo C., Xia Y., Zhou B., Li S., Dooley L. T., Goldstein N. H., Menter A.; ACCEPT Study Group (2010) Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 118–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reddy M., Torres G., McCormick T., Marano C., Cooper K., Yeilding N., Wang Y., Pendley C., Prabhakar U., Wong J., Davis C., Xu S., Brodmerkel C. (2010) Positive treatment effects of ustekinumab in psoriasis: analysis of lesional and systemic parameters. J. Dermatol. 37, 413–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kryczek I., Bruce A. T., Gudjonsson J. E., Johnston A., Aphale A., Vatan L., Szeliga W., Wang Y., Liu Y., Welling T. H., Elder J. T., Zou W. (2008) Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-gamma: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 181, 4733–4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piskin G., Sylva-Steenland R. M., Bos J. D., Teunissen M. B. (2006) In vitro and in situ expression of IL-23 by keratinocytes in healthy skin and psoriasis lesions: enhanced expression in psoriatic skin. J. Immunol. 176, 1908–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nickoloff B. J., Wrone-Smith T. (1999) Injection of pre-psoriatic skin with CD4+ T cells induces psoriasis. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 145–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boyman O., Hefti H. P., Conrad C., Nickoloff B. J., Suter M., Nestle F. O. (2004) Spontaneous development of psoriasis in a new animal model shows an essential role for resident T cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Exp. Med. 199, 731–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kerschbaumer A., Fenzl K. H., Erlacher L., Aletaha D. (2016) An overview of psoriatic arthritis - epidemiology, clinical features, pathophysiology and novel treatment targets. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 128, 791–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raychaudhuri S. P., Wilken R., Sukhov A. C., Raychaudhuri S. K., Maverakis E. (2017) Management of psoriatic arthritis: early diagnosis, monitoring of disease severity and cutting edge therapies. J. Autoimmun. 76, 21–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.