Abstract

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), a common form of localisation-related epilepsy, is characterised by focal seizures and accompanied by variety of neuropsychiatric symptoms. This form of epilepsy proves difficult to manage as many anticonvulsant and psychotropic medications have little to no effect on controlling the seizure and neuropsychiatric symptoms respectively. The authors, report a patient with TLE and recurrent seizures that were refractory to multiple classes of antiepileptic therapy. Additionally, she exhibited psychosis, depression and irritability that required antipsychotic medication. After several years of poorly controlled seizure disorder, the patient underwent anterior temporal lobectomy and amygdalohippocampectomy, which proved beneficial for seizure control, as well as her neuropsychiatric symptoms. While it is common to treat refractory temporal lobe epilepsy with surgical interventions, there is little literature about it also treating the neuropsychiatric symptoms. This case underscores both the neurological and psychiatric benefits following surgical intervention for patients with TLE.

Keywords: psychiatry, epilepsy and seizures

Background

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), a common form of localisation-related epilepsies, is characterised by focal seizures with impaired awareness and consciousness. While it can arise from metabolic, genetic or infectious causes, mesial TLE is most frequently associated with hippocampal sclerosis. Central nervous system infection, brain injury, tumours, autoimmune encephalitis, vascular and congenital malformations, and perinatal injury are other causes of TLE.1 2

The association between mesial TLE and neuropsychiatric symptoms has been reported for years now. Associated impairments of memory and cognition are reported, and severity of abnormalities in cognition has been correlated with severity and bilateral abnormalities on MRI.1 3 4 Similarly association between mesial TLE and depression, anxiety and other psychiatric comorbidities is reportedly common.5

In a retrospective study of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis, only 24.7% were able to maintain freedom from seizure for more than 1 year after two sequential trials of antiepileptic drugs.6 The current recommendations from the American Academy of Neurology state that patients with epilepsy should be referred to an epilepsy centre after trials of 2 antiepileptic agents fail, and surgery should be considered.7 The effects of surgical management on psychiatric comorbidity is currently unclear.8

Case presentation

A 32-year-old immigrant woman, diagnosed with epilepsy at 14 years of age, presented to the doctor’s office with poorly controlled seizures with a frequency of about 15 seizures per month. Her seizures were characterised as ‘blank staring spell’ lasting for 30 to 60 s followed by generalised, tonic–clonic seizure lasting around 2 to 3 min, followed by a short period (less than 5 min) of postictal confusion. The patient denied aura preceding her seizures. This was the first time the patient was accessing outpatient care for her seizures, as she was new to the USA and mentioned was unable to access regular medical care in her previous country of residence.

The patient denied any other medical comorbidity and denied family history of seizure disorder. She had multiple emergency room visits related to her seizures, but had never been on stable maintenance antiepileptic regimen due to poor access to medical care. She was living with her family and denied smoking, alcohol or recreational drug use. Patient had a normal physical examination, including a normal neurological examination.

Over the next few years, the patient was administered various antiepileptic medication combinations with increased dosing (table 1); however, the patient continued to have seizures 4–5 times a month.

Table 1.

Antiepileptic medication regimens administered to the patient prior to surgical intervention

| Drugs | |

| Visit 1 (0 month) | Phenytoin 400 mg; levetiracetam 750 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 2 (3 month f/u) | Phenytoin 400 mg;levetiracetam 1000 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 3 (5 month f/u) | Oxcarbazepine 600 mg twice daily; levetiracetam 1500 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 4 (8 month f/u) | Oxcarbazepine 900 mg twice daily; levetiracetam 1500 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 5 (14 month f/u) | Oxcarbazepine 1200 mg twice daily; Levetiracetam 1500 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 6 (26 month f/u) | Lacosamide 150 mg twice daily; oxcarbazepine 600 mg twice daily; levetiracetam 750 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 7 (27 month f/u) | Lacosamide 150 mg twice daily; oxcarbazepine 1200 mg twice daily; levetiracetam 1500 mg twice daily. |

| Visit 8 (37 month f/u) | Lacosamide 200 mg twice daily; oxcarbazepine 1200 mg twice daily; levetiracetam 1500 mg twice daily. |

Alongside her epilepsy, she manifested symptoms of depression, irritability and psychosis. Onset of psychiatric symptom mimicked onset of her seizure disorder, and patient did not notice any improvement or worsening while being on the antiepileptic medication regimen. Most commonly described symptoms of depression for the patient included, sadness, poor concentration, insomnia, hopelessness and anhedonia. These symptoms at times were disabling and worsened her quality of life. She had never been on antidepressant therapy in the past and had not accessed psychiatric care in the past. Similarly, the patient experienced paranoid delusions, where she felt that people were constantly monitoring her and trying to harm her. The psychotic symptoms were intermittent and progressively worsening. The patient had noted worsening of her delusions, in association to worsening of her seizure frequency and severity. The patient was started on aripiprazole to target both her psychosis and mood symptoms and titrated to a dose of 15 mg/day, and her psychiatric symptoms showed significant improvement.

Investigations

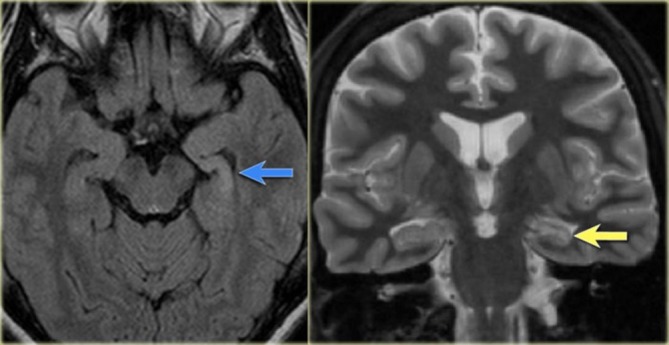

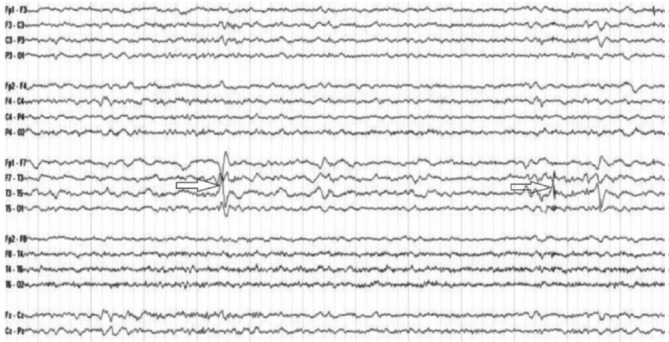

To further investigate her refractory epilepsy, a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study was performed with normal findings. MRI of brain showed significant sclerosis of the left hippocampus (figure 1), without significant changes in the amygdala. The interictal electroencephalogram (EEG) demonstrated epileptiform sharp waves over the left temporal area, pointing towards TLE (figure 2). MRI and the EEG findings confirmed the diagnosis of mesial TLE secondary to sclerosis of the left hippocampus.

Figure 1.

MRI brain demonstrating hyperintensity of the left hippocampus on the axial FLAIR image (blue arrow) and atrophy of the left hippocampus on coronal images (yellow arrow).

Figure 2.

The interictal electroencephalogram demonstrating epileptiform sharp waves over the left temporal area.

Treatment

After several years of poorly-controlled seizure disorders, the patient agreed to surgical intervention. She underwent a left temporal craniotomy with anterior temporal lobectomy and amygdalohippocampectomy. Surgical pathology of the resected portion, demonstrated subcortical gliosis of the left anterior temporal lobe and severe depopulation of the left hippocampus affecting all areas with focal dispersion. The absence of granule cells of the dentate suggested severe hippocampal sclerosis.

Outcome and follow-up

This procedure proved beneficial for the patient as there were no complications and her seizure occurrence resolved. Remarkably, this procedure improved her neuropsychiatric symptoms shortly afterwards. On her psychiatric outpatient appointment, 2 months postsurgery, the patient denied any current psychiatric symptoms. The patient was tapered off aripiprazole and was successfully tapered off her antipsychotic medication with no recurrence of her psychosis 6 months postsurgery. Similarly, the patient tapered off her antiepileptic medications without any recurrence of seizures 12 months postsurgery.

Discussion

The authors report a case of refractory TLE with psychiatric symptoms, where a complete resolution of seizures as well as psychiatric symptoms was obtained by surgical intervention. Surgical management has been shown to be superior to pharmacotherapy in management of seizures in patient with mesial TLE, in both a randomised controlled trial,9 as well as the meta-analysis in the American Academy of Neurology practice parameter for temporal lobe resections for epilepsy.8 Surgical resection of the seizure-generating region is the preferred procedure and most commonly involves anteromedial temporal lobe resection to treat mesial temporal sclerosis. A randomised controlled trial demonstrated that at 1 year postsurgery, the patients in the surgical group had fewer seizures and a significantly better quality of life (p<0.001 for both comparisons) than the patients in the medical group.9 Further, among patients with newly diagnosed mesial TLE failing trials of 2 antiepileptic agents, resective surgery plus antiepileptic therapy resulted in a lower probability of seizures during year 2 of follow-up than continued antiepileptic therapy alone.10 Based on these results, it is recommended that mesial TLE patients, having failed two or more antiepileptic drug regimens, be referred to epilepsy centres and be considered for surgery.10

When approaching cases of TLE, it is important to consider anatomical changes in temporal lobe structures. While hippocampal sclerosis is a classic finding on MRI, amygdala enlargement (AE) with no changes in the hippocampus can also be found. A volumetric study on amygdala done in a group of patients with both TLE and AE, demonstrate that those responsive to medical therapy showed a significant (p<0.01) decrease in amygdala volume post treatment.11 In contrast, those refractory to antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment displayed no volume changes over time.11 The study also highlighted that psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety and depression, are frequently associated with AE, with 90% of patients in this study suffering from one or both.11 Another study that used quantitative MRI measurements of TLE patients with and without psychopathology found a highly significant enlargement of the left and right amygdala in dysthymic patients (right side p<0.000 and left side p=0.001).12 While patients with TLE may be considered ‘imaging-negative,’ because of the absence of hippocampal sclerosis, AE should not be overlooked, particularly in individuals with comorbid psychopathology.

As mentioned earlier, the effects of surgical management on psychiatric comorbidity is currently unclear.8 A longitudinal multicentre study, reported depression and anxiety in 22·1% and 24·7% of patients, respectively, declining gradually postsurgery over 2 years to 11·4% and 12·3%, respectively. The significant reduction in prevalence of depression and anxiety in these patient was further associated with improved seizure control.13 However, the influence of surgery on psychotic symptoms is not well-known. On the contrary, reports of 1%–5% patients developing psychosis and 4%–30% of patients developing new affective disorders post-surgery are also reported.8

Though this report presents a single patient outcome, it still demonstrates benefits of surgical intervention in treatment resistant TLE. The procedure not only resolved the patient’s seizure, but her psychiatric symptoms as well. Resolution of depression and psychosis following temporal lobectomy are not well-documented and thus noteworthy.

Learning points.

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the most common localisation-related epilepsy, and hippocampal sclerosis is the most common underlying aetiology.

Association between mesial TLE and depression, anxiety and other psychiatric comorbidities is commonly reported.

Surgical management has been shown to be superior to pharmacotherapy in management of seizures in patients with mesial TLE.

Surgical interventions have the potential added benefit of treating psychiatric comorbidities as well as managing seizures due to TLE.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors (LS and GC) have contributed towards reviewing the literature and writing this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Soeder BM, Gleissner U, Urbach H, et al. Causes, presentation and outcome of lesional adult onset mediotemporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:894–9. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.165860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harvey AS, Grattan-Smith JD, Desmond PM, et al. Febrile seizures and hippocampal sclerosis: frequent and related findings in intractable temporal lobe epilepsy of childhood. Pediatr Neurol 1995;12:201–6. 10.1016/0887-8994(95)00022-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dabbs K, Jones J, Seidenberg M, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive phenotypes in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009;15:445–51. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Busch RM, Frazier T, Chapin JS, et al. Role of cortisol in mood and memory in patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 2012;78:1064–1068. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8efb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanchez-Gistau V, Sugranyes G, Baillés E, et al. Is major depressive disorder specifically associated with mesial temporal sclerosis? Epilepsia 2012;53:386–392. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pohlen MS, Jin J, Tobias RS, et al. Pharmacoresistance with newer anti-epileptic drugs in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsy Res 2017;137:56–60. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engel J Jr, Wiebe S, French J, et al. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; American Epilepsy Society; American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Practice parameter: temporal lobe and localized neocortical resections for epilepsy: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, in association with the American Epilepsy Society and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Neurology 2003;60:538–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spencer S, Huh L. Outcomes of epilepsy surgery in adults and children. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:525–37. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70109-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, et al. Effectiveness and Efficiency of Surgery for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2001;345:311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Engel J, McDermott MP, Wiebe S, et al. Early surgical therapy for drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy: a randomized trial. JAMA 2012;307:922 10.1001/jama.2012.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lv RJ, Sun ZR, Cui T, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy with amygdala enlargement: a subtype of temporal lobe epilepsy. BMC Neurol 2014;14:194 10.1186/s12883-014-0194-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tebartz van Elst L, Woermann FG, Lemieux L, et al. Amygdala enlargement in dysthymia--a volumetric study of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Biol Psychiatry 1999;46:1614–23. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00212-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology 2005;65:1744–9. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]