Abstract

Non-typhoidal Salmonella spp.are Gram-negative bacilli, which typically cause a clinical picture of gastroenteritis and, less commonly, patients may become a chronic carrier of the pathogen within their gallbladder. We describe a rare clinical presentation of a non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. infection as acute calculus cholecystitis in an adult patient. Salmonella enterica subsp. Salamae (ST P4271) was grown from cholecystostomy fluid, and the patient subsequently underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy that demonstrated a necrotic gallbladder fundus. We advise that microbiological sampling of bile is essential, especially in the context of foreign travel, to detect unusual pathogens as in this case or common pathogens that may have unusual antimicrobial resistance. Given the necrotic gallbladder as in this case, we also advise that early cholecystectomy should be strongly considered in these patients.

Keywords: general surgery, pancreas and biliary tract, infectious diseases

Background

Salmonella spp. are Gram-negative bacilli that may cause gastroenteritis or enteric (typhoid) fever following consumption of contaminated food or water.1 2 Complications are usually limited to dehydration and electrolyte disturbances although less commonly toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, distant seeding or more systemic effects may occur.1 2 Following infection with Salmonella enterica serovar typhi or Paratyphi (S. typhi or S. paratyphi), patients may become an asymptomatic chronic carrier within their gallbladder,2 which has long-term sequelae such as gallbladder malignancy.3 This paper describes a rare clinical presentation of a non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. infection as acute calculus cholecystitis in an adult patient.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old man presented the day after returning from a prolonged stay in Guinea with a 5-day history of severe epigastric and right upper quadrant pain associated with fevers, vomiting and loose stools. His only medical history was of reflux for which he took esomeprazole 40 mg once daily. On examination, he was tachycardic at 117 bpm, tender in the right upper quadrant and was Murphy’s sign positive. His blood tests showed total white cell count 16.5×109/L (4.2–10.6×109/L), C reactive protein 323 mg/L, bilirubin 22 (0–21 µmol/L), alanine aminotransferase 106 (0-45 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase 97 (30-130 IU/L) and amylase 131 (0-90 IU/L). Erect chest and abdominal radiographs were unremarkable. The clinical impression was of acute cholecystitis, and the patient was commenced on intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanate.

Investigations

An ultrasound scan demonstrated a thick-walled (1.3 cm) gallbladder with pericholecystic fluid and a solitary 1.7 cm gallstone at the neck of the gallbladder. The patient’s antimicrobials were escalated to gentamicin and piperacillin-tazobactam after persisting fever. The patient had a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography on day 3, which confirmed calculus cholecystitis with no biliary duct dilatation or filling defect within the common bile duct.

Outcome and follow-up

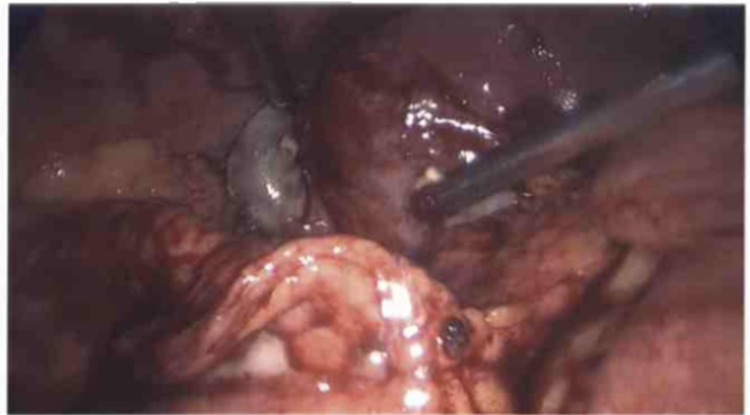

After 4 days of persisting sepsis, the patient underwent a cholecystostomy for source control. The bile grew Salmonella enterica subsp. Salamae (sequence type P4271), and on day 7, the patient’s antibiotics were switched to ceftriaxone and metronidazole. On day 9, the patient underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which demonstrated a necrotic gallbladder fundus (figures 1 and 2). The patient recovered and was discharged postoperative day 4 on oral ciprofloxacin.

Figure 1.

Necrotic fundus of gallbladder visualised during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Figure 2.

Dissection of necrotic fundus of gallbladder during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Discussion

Salmonella spp. are endemic in many areas worldwide and are responsible for significant mortality and morbidity. While deaths from salmonellosis are infrequent in the UK, it is a not uncommon cause of enteritis. Salmonellosis typically presents as either an enteric (typhoid) fever (S. typhi or S. paratyphi) or gastroenteritis (non-typhoidal Salmonella spp.).1 2 Up to 5% of acute enteric (typhoid) fever infections will go on to develop chronic carriage of S. typhi or S. paratyphi within their gallbladder.4 However, it is very rare for non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. to present as an acute calculus Salmonella spp. cholecystitis.

Acute acalculus cholecystitis occurring in association with enteric (typhoid) fever may occur as a secondary event complicating the predominating endotoxin-mediated sepsis.5 Calculus cholecystitis caused by enteric (typhoid) fever is only slightly more common yet just 5 in a series of 6250 cases of salmonellosis presented in this manner.6 For non-typhoidal Salmonella spp., acute calculus cholecystitis (as in this case) is a much rarer clinical picture and has only been reported in a young child7 and in an Intensive Therapy Unit (ITU) patient.8 While S. typhi and S. paratyphi have been cultured from between 0.6% and 5.8% of gallbladders following cholecystectomy/biliary drainage,4 the epidemiology of non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. from these sample types is not clear.

Current evidence and guidelines advocate acute cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis within 1 week of symptom onset.9 Conservative management followed by delayed cholecystectomy is appropriate if there is a longer delay to surgery, in view of the development of significant inflammatory sequelae. In this case, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed 14 days after symptom onset, and given the gallbladder necrosis seen intraoperatively (figure 1), this likely avoided further complications.

Learning points.

In the context of foreign travel, microbiological sampling of bile from cholecystostomies or intraoperatively is essential.

Detecting unusual pathogens, or common pathogens with unusual antimicrobial resistance, necessitates alternate antimicrobial regimes that can avert significant morbidity and mortality.

The higher chance of necrotic complications in Salmonella spp. cholecystitis means early cholecystectomy should be strongly considered.

Acknowledgments

LSPM acknowledges support from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (HPRU) in Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance at Imperial College London in partnership with Public Health England.

Footnotes

FJ and JJC contributed equally.

Contributors: FJ and JJC conducted the literature search and drafted the initial manuscript. HG and LSPM wrote sections relevant to their areas of expertise and reviewed redrafts of the manuscript. All authors agreed the final submitted version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health.

Competing interests: LSPM has consulted for bioMerieux (2013), DNAelectronics (2015) and Dairy Crest (2017–2018); received speaker fees from Profile Pharma (2018) and Pfizer (2018-2019); received research grants from the NIHR (2013–2018) and Leo Pharma (2016); and received educational support from Eumedica (2016–2017).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Hohmann EL. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:263–9. 10.1086/318457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, et al. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1770–82. 10.1056/NEJMra020201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Di Domenico EG, Cavallo I, Pontone M, et al. Biofilm producing salmonella typhi: chronic colonization and development of gallbladder cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:1887 10.3390/ijms18091887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gunn JS, Marshall JM, Baker S, et al. Salmonella chronic carriage: epidemiology, diagnosis, and gallbladder persistence. Trends Microbiol 2014;22:648–55. 10.1016/j.tim.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan FY, Elouzi EB, Asif M. Acute acalculous cholecystitis complicating typhoid fever in an adult patient: a case report and review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis 2009;7:203–6. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lalitha MK, John R. Unusual manifestations of salmonellosis--a surgical problem. Q J Med 1994;87:301–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beiler HA, Kuntz C, Eckstein TM, et al. Cholecystolithiasis and infection of the biliary tract with Salmonella Virchow--a very rare case in early childhood. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1995;5:369–71. 10.1055/s-2008-1066246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mofredj A, Danon O, Cadranel JF, et al. Acute cholecystitis and septic shock due to salmonella virchow. QJM 2000;93:389–90. 10.1093/qjmed/93.6.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gallstone disease. The National institue for health and care excellence clinical guideline. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg188 (Accessed 27 Sep 2018).