Abstract

We present the case of a 30-year-old woman with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) as a complication of pre-eclampsia in the early postpartum period. PRES is a rare neurological disorder which causes non-specific neurological symptoms such as headache, seizures and visual disturbances. It generally has a good prognosis, but severe complications can arise. Therefore, early recognition and treatment are paramount. Pre-eclampsia is a multiorgan disease and is associated with both maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. Neurological symptoms occurring in the postpartum period indicate pre-eclampsia until proven otherwise. This case report was written to stress the attention on this rare complication of pre-eclampsia. When a patient in the postpartum period presents with a combination of seizures, disturbed vision and headache, PRES should always be kept in mind.

Keywords: obstetrics and gynaecology, pregnancy

Background

We report a case of a 30-year-old woman with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) caused by pre-eclampsia in the early postpartum period.

PRES is a rare neurological disorder with an unclear pathophysiology.1 The first case of PRES was described in 1996 by Hinchey and Schmutzhard. Since only limited research is executed, the available data on this condition are sparse.2 PRES is characterised by vasogenic oedema causing non-specific neurological signs such as headache, seizures and visual disturbances.1 3 The prognosis is good and most of the patients fully recover without any residual complaints. Since severe complications such as status epilepticus, cerebral ischemia, intracerebral haemorrhage or intracranial hypertension can arise, early recognition and treatment are paramount.1

Pre-eclampsia appears in nearly 5% of pregnancies. It is characterised by gestational hypertension and proteinuria.4 5 Pre-eclampsia is acknowledged to be an important cause of PRES.3 4 The pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia is not fully understood; however, endothelial injury seems to be involved.6 Besides PRES, a myriad of other complications can occur. Therefore, early diagnosis and precautionary actions are important.5 7

Case presentation

A 30-year-old woman, gravida 1 para 0, presented at the delivery room. At the moment of arrival, she was full term and had already dilated to 3 cm. After an uncomplicated labour of 3 hours, she delivered a healthy baby boy. There was no need of epidural analgesia during labour.

The pregnancy was complicated with Hashimoto’s hypothyroid and gestational diabetes. l-Thyroxine was substituted for hypothyroid, with normalisation of thyroid function as result. Glycaemias were within a normal range with a diet, without the need for insulin. Her medical history mentioned hypertension which was efficiently treated with nebivolol. This beta-blocker was discontinued at the beginning of her pregnancy. No other antihypertensive agent was started because the tensions remained stable during the entire gestation period and labour. The family history showed that both her mother and uncle suffered from hypertension.

Four hours after delivery, the midwife noticed neurological deterioration of the patient. All of a sudden, she was somnolent and reacted only to painful stimuli. Her hands were cramped, and she had ptosis of the left eyelid and anisocoria.

Investigations

Her blood pressure was tremendously elevated, up to 220/125 mm Hg. Other vital parameters were within the normal range. A lab panel was normal, except for leucocytosis (19×109/L). An urgent CT of the brain and CT angiography showed no signs of bleeding, dissection or thrombosis. Nevertheless, a spasm of the left internal carotid artery was suspected.

Differential diagnosis

An eclamptic insult was assumed to be most likely. Thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinus and other neurological disorders such as bleeding and ischemia were retained as differential diagnoses.

Treatment

Because of the low Glasgow Coma Scale (4/15) she was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for intubation and sedation. Intravenous nicardipine and magnesium were started for blood pressure control.

Outcome and follow-up

A few hours after transfer to the ICU, the patient could be awakened and extubated. After she woke up, she still had ptosis of the left eyelid and her neurological function was still mildly impaired. The patient indicated a blurred vision of both eyes.

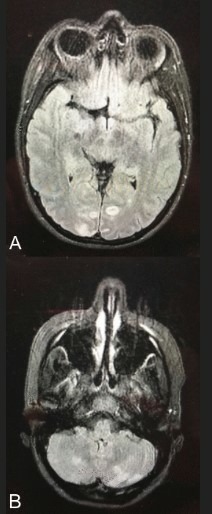

MRI of the brain was performed to further assess brain lesions. The MRI showed hyperintensities on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images at the cerebellum, occipital cortex and thalami, congruent with PRES. (figure 1)

Figure 1.

Brain MRI showing hyperintensities on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images in the occipital cortex (A) and in the cerebellum (B).

On the second day, the lab panel showed low platelets (119×109/L), elevation of the liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) 49 U/L) and haemolysis. Urine analysis demonstrated the presence of proteinuria (310 mg/24 hours). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of PRES and eclampsia due to the haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets syndrome.

Magnesium could be stopped 48 hours after delivery. Tension remained stable after discontinuation of nicardipine and switch to labetalol 100 mg two times a day.

During the first night at the ICU, a short run of ventricle tachycardia was noticed. Cardiological check-up with a 12-lead ECG and echocardiography did not show remarkable findings.

In the course of the following days her neurological and visual functions gradually improved. Ophthalmologic investigations did not show any abnormalities. Progressive mobilisation was provided by a physiotherapist and soon she could start to breastfeed her son. Six days after delivery she could leave the hospital in good health.

A few months after delivery, residual zones of infarction in the posterior circulation were seen on brain MRI. Neurological and neuropsychological re-evaluation showed almost complete remission, except for a mild cognitive and phatic impairment and a mild visual field dysfunction of the right eye. She was referred to a speech therapist for rehabilitation and psychological support was offered.

Discussion

PRES is a rare complication of pre-eclampsia.1 8 It causes non-specific neurological symptoms such as headache, seizures or visual disturbances and is associated with a lot of conditions such as hypertension, renal failure or infections.1 9 10 Pre-eclampsia is known as one of the most important causes of PRES.1 10 11 Pre-eclampsia originates mostly during the second or third trimester of pregnancy, although in 5% of the cases it can also develop during the puerperium.12 13

The pathophysiology of both conditions is not fully understood, but either of them is associated with endothelial injury.1 3 4 11 14 Dysregulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) might be the underlying mechanism leading to abnormal placental development in patients with pre-eclampsia.15–17 miRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules that are involved in several biological pathways such as cell development, differentiation and apoptosis.17 Dysregulation of miRNAs might cause inadequate trophoblast invasion in the spiral arterial wall, leading to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and inadequate placental vascularisation.11 14 17

Generalised endothelial damage, as present in pre-eclampsia, may result in cerebral dysfunction.11 Several mechanisms are conceivable including trans-endothelial leakage and oedema formation, higher local exposure to free radicals, hypoxia and excess excitatory toxins.1 4 18 Accordingly, eclampsia and convulsions will occur if this takes place at the motor cortex, whereas lesions at the level of the occipital cortex are related to PRES.3

When a patient in the postpartum period presents with a combination of seizures, disturbed vision and headache, PRES should always be kept in mind.11 Brain MRI is the most suitable diagnostic tool.1 19 CT, electroencephalography and other diagnostic tests can be used to exclude other disorders.20 Thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinus must be excluded as well since it is the most frequent cerebrovascular disorder in the puerperium.9

Hypertension has to be reversed using antihypertensive drugs and magnesium sulfate should be started to prevent or treat seizures.5 11

The prognosis is good and 75%–90% of the patients fully recover.21 Complications such as status epilepticus, intracranial haemorrhage and cerebral ischemia are rare but have to be feared because they can be life-threatening. The mortality rate amounts to 3%–6% of the patients.22 Pre-eclampsia has a risk for recurrence of 7%–15%; nevertheless, recurrence of PRES is rare.23

Since these conditions are associated with both maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality, early diagnosis and prevention of clinical manifestations must be pursued.4–7 17 A lot of research is aimed at the detection of biomarkers in order to identify women at risk for developing pre-eclampsia. Some serum markers are suggested as biomarkers, including (anti-)angiogenic modulators such as vascular endothelial growth factor, placental growth factor (PlGF), soluble endoglin and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1).24 For example, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio is suggested to be a predictor for the short-term absence of pre-eclampsia in women with suspected pre-eclampsia.25 Other authors suggest endothelial progenitor cells, natural killer cells, neurokinin B and miRNAs as biomarkers for the early detection of pre-eclampsia.17 26–28

Besides early detection and identification of women with pre-eclampsia, preventive measures can be taken. The ASPRE trial showed that the use of low dose aspirin from 11 to 14 until 36 weeks gestation in woman with an increased risk for developing pre-eclampsia might lower the incidence of pre-eclampsia compared with placebo.29 Also the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists advises low dose aspirin at 12 weeks of gestation until delivery in women with previous early onset pre-eclampsia and delivery before 34 weeks of gestation or women with pre-eclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.5 Also supplementation of docosahexaenoic acid is suggested for the prevention of pre-eclampsia but still needs further investigation.30

In conclusion, the emergence of neurological symptoms in the postpartum period indicates pre-eclampsia until proven otherwise. Magnesium sulfate and/or antihypertensive drugs have to be started to prevent further complications. A lot of questions considering the pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of both pre-eclampsia and PRES remain unanswered. Further research is needed to get a comprehensive picture of these conditions.

Learning points.

Neurological symptoms occurring in the postpartum period indicate pre-eclampsia until proven otherwise.

When a patient in the postpartum period presents with a combination of seizures, disturbed vision and headache, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome should always be kept in mind.

Thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinus must be excluded as well because it is the most frequent cerebrovascular disorder during the puerperium.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all persons that were involved in the care of this patient and also the patient for her permission to write this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: For this manuscript, literature search was done by JV, FP and PD. This manuscript was written by JV and FP. The final manuscript was approved by YJ and PD. FP and PD took care of the follow-up of this patient.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Fischer M, Schmutzhard E. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. J Neurol 2017;264:1608–16. 10.1007/s00415-016-8377-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 1996;334:494–500. 10.1056/NEJM199602223340803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:914–25. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00111-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDermott M, Miller EC, Rundek T, et al. Preeclampsia: Association With Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome and Stroke. Stroke 2018;49:524–30. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberts JM. Hypertension in Pregnancy. US: American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roberts JM, Lain KY. Recent Insights into the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Placenta 2002;23:359–72. 10.1053/plac.2002.0819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2017;317:1661–7. 10.1001/jama.2017.3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, et al. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;170:1–7. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang L, Wang Y, Shi L, et al. Late postpartum eclampsia complicated with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a case report and a literature review. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2015;5:909–16. 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.12.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sudulagunta SR, Sodalagunta MB, Kumbhat M, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome(PRES). Oxf Med Case Reports 2017;2017:omx011 10.1093/omcr/omx011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hammer ES, Cipolla MJ. Cerebrovascular dysfunction in preeclamptic pregnancies. Curr Hypertens Rep 2015;17:64 10.1007/s11906-015-0575-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:181–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Al-Safi Z, Imudia AN, Filetti LC, et al. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia and eclampsia: demographics, clinical course, and complications. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:1102–7. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318231934c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou Y, Damsky CH, Fisher SJ. Preeclampsia is associated with failure of human cytotrophoblasts to mimic a vascular adhesion phenotype. One cause of defective endovascular invasion in this syndrome? J Clin Invest 1997;99:2152–64. 10.1172/JCI119388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Sapia F, et al. miRNA expression for early diagnosis of preeclampsia onset: hope or hype? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:817–21. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1296426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vashukova ES, Glotov AS, Fedotov PV, et al. Placental microRNA expression in pregnancies complicated by superimposed pre-eclampsia on chronic hypertension. Mol Med Rep 2016;14:22–32. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jairajpuri DS, Almawi WY. MicroRNA expression pattern in pre-eclampsia (Review). Mol Med Rep 2016;13:2351–8. 10.3892/mmr.2016.4846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mannaerts D, Faes E, Gielis J, et al. Oxidative stress and endothelial function in normal pregnancy versus pre-eclampsia, a combined longitudinal and case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:60 10.1186/s12884-018-1685-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bartynski WS, Boardman JF. Distinct Imaging Patterns and Lesion Distribution in Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2007;28:1320–7. 10.3174/ajnr.A0549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kastrup O, Gerwig M, Frings M, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): electroencephalographic findings and seizure patterns. J Neurol 2012;259:1383–9. 10.1007/s00415-011-6362-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roth C, Ferbert A. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: long-term follow-up. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2010;81:773–7. 10.1136/jnnp.2009.189647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moon S-N, Jeon SJ, Choi SS, et al. Can clinical and MRI findings predict the prognosis of variant and classical type of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)? Acta radiol 2013;54:1182–90. 10.1177/0284185113491252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2011;25:391–403. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Early pregnancy prediction of preeclampsia. 2018. Internet.

- 25. Zeisler H, Llurba E, Chantraine F, et al. Predictive value of the sflt-1:Plgf ratio in women with suspected preeclampsia. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2016;374:13–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salman H, Shah M, Ali A, et al. Assessment of relationship of serum neurokinin-b level in the pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia: A case–control study. Adv Ther 2018;35:1114–21. 10.1007/s12325-018-0723-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laganà AS, Giordano D, Loddo S, et al. Decreased Endothelial Progenitor Cells (EPCs) and increased Natural Killer (NK) cells in peripheral blood as possible early markers of preeclampsia: a case-control analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;295:867–72. 10.1007/s00404-017-4296-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Timofeeva AV, Gusar VA, Kan NE, et al. Identification of potential early biomarkers of preeclampsia. Placenta 2018;61:61–71. 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rolnik DL, Wright D, Poon LCY, et al. ASPRE trial: performance of screening for preterm pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:492–5. 10.1002/uog.18816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou SJ, Yelland L, McPhee AJ, et al. Fish-oil supplementation in pregnancy does not reduce the risk of gestational diabetes or preeclampsia. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1378–84. 10.3945/ajcn.111.033217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]