Abstract

Sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland is a rare occurrence. Parathyroid sarcoidosis is usually associated with parathyroid adenomas, and, therefore, hypercalcaemia is a common presentation of this entity. We present a case of parathyroid sarcoidosis and review the world literature regarding this rare condition. A woman with a history of diffuse large B cell lymphoma underwent a surveillance positron emission tomography scan that showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in multiple thoracic and abdominal lymph nodes and in a left upper extremity soft tissue mass. Biopsy of the soft tissue mass showed non-caseating granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis. Blood work showed a serum calcium of 11.1 mg/dL with an intact serum parathyroid hormone of 92 pg/dL. Primary hyperparathyroidism was suspected. A neck ultrasound and sestamibi parathyroid scintigraphy demonstrated a parathyroid nodule. She underwent surgical resection, and the histopathology revealed a parathyroid adenoma and non-caseating granulomata consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Keywords: endocrine system; respiratory system; ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology; calcium and bone

Background

Sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland is extremely rare and usually associated with the presence of a parathyroid adenoma. Because of this association, hypercalcaemia is a common presentation of sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland. The clinician may mistakenly attribute the hypercalcaemia to the much more frequent cause, sarcoidosis-induced vitamin D dysregulation. We present a patient with sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland and review the medical literature concerning this condition.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old white woman had been previously diagnosed with diffuse large B cell lymphoma 7 years prior for which she underwent chemotherapy resulting in a complete response. She subsequently underwent a surveillance positron emission tomography scan that showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in mediastinal, pericardial and abdominal lymph nodes, a soft tissue mass in the left upper extremity, and in the left ventricular myocardium. Biopsy of the soft tissue mass showed discrete non-caseating granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis (figure 1). She was placed on 30 mg of prednisone daily for presumed cardiac sarcoidosis and referred to our clinic.

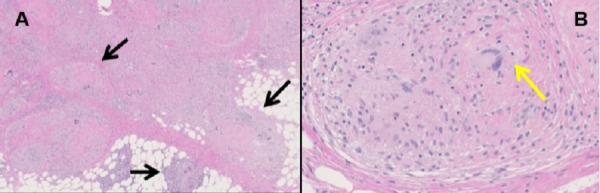

Figure 1.

Sarcoidosis involving the soft tissue. (A) Soft tissue (H&E stain, 40×) with a confluent nodular mass aggregate of multiple discrete non-caseating granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis (black arrows). The granulomas are bridged by dense eosinophilic hyaline fibrosis with intermixed chronic inflammation. (B) High-power image of soft tissue granuloma (200×) showing a discrete micronodular aggregate of epithelioid histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells (yellow arrow) and sparse admixed lymphocytes cuffed by dense laminated eosinophilic hyaline fibrosis. Acid-fast and Grocott-Gomori’s methamine silver stains were negative for mycobacterial and fungal organisms.

She denied shortness of breath, orthopnea, palpitations, syncope, haematuria, kidney stones, atraumatic bone fractures, voice changes, excessive thirst or urination, abdominal pain, constipation or bone pain. She had no history of tuberculosis or tuberculosis exposure and was a lifetime non-smoker. Physical examination was normal.

Investigations

Initial laboratory data demonstrated normal complete blood count. Electrolytes and liver function tests were also normal. Her serum creatinine and calcium level were elevated at 1.4 and 11.1 mg/dL, respectively. Based on these results, the patient had the following additional serum levels determined: 25(OH) vitamin D 22.7 ng/mL (normal: 30–50 ng/mL), 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D 53 pg/mL (normal: 18–78 pg/mL) and intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) 92 pg/mL (normal: 12–88 pg/mL). Urinary protein creatinine ratio was minimally elevated, and 24-hour urinary excretion of calcium was high, 307 mg (normal: 100–250 mg/24 hours). These blood and urine test results were consistent with primary hyperparathyroidism and not with sarcoidosis-induced vitamin D dysregulation. For these reasons, she underwent a neck ultrasound that revealed a 1 cm hypoechoic nodule inferior to the lower pole of the right thyroid lobe. Sestamibi parathyroid scintigraphy demonstrated a focus of increased radiotracer activity at the same location, highly suspicious for a parathyroid adenoma. A preoperative assessment of bone mineral density (BMD) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was not performed.

Differential diagnosis

The aetiology for hypercalcaemia in this patient was parathyroid adenoma, as evidenced by elevated PTH, 24-hour urinary calcium excretion and a sestamibi parathyroid scintigraphy demonstrating increased radiotracer activity. However, possibility of an underlying malignancy should always be considered, especially in a patient with history of lymphoma. Unlike primary hyperparathyroidism, serum PTH level is low in hypercalcaemia associated with malignancy as well as vitamin D dysregulation.

Treatment

She underwent surgical resection of the parathyroid adenoma with intraoperative PTH monitoring showing normalisation of the PTH level. The histopathology confirmed a parathyroid adenoma with degenerative atypia and non-caseating granuloma consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland (figure 2). Stains for fungal and mycobacterial pathogens were negative.

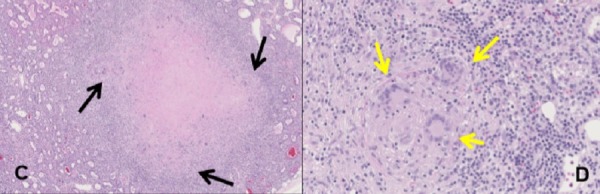

Figure 2.

Granulomatous involvement of the parathyroid gland in a sarcoidosis patient with a parathyroid adenoma. (A) Hypercellular parathyroid, consistent with parathyroid adenoma (40×), with a nodular aggregate of discrete non-necrotising granulomas (black arrows) bridged by dense hyaline fibrosis. (B) High-power image of parathyroid granuloma (200×) showing a discrete micronodular aggregate of epithelioid histiocytes with admixed multinucleated giant cells (yellow arrows) and admixed lymphocytes.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s hypercalcaemia resolved after parathyroidectomy.

Discussion

We have described a patient with sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland presenting with primary hyperparathyroidism. Including the present case, we have identified seven confirmed cases of sarcoid involvement of the parathyroid gland in the medical literature (table 1). All these patients presented with hypercalcaemia. Parathyroid adenomas were histologically confirmed in six of these seven cases, and in the remaining case, the serum PTH was elevated, and hyperplasia of the parathyroid gland was demonstrated without evidence of an adenoma.1–5 Histologic examination revealed non-caseating granulomas within the adenoma in five cases,1 3–5 adjacent to the adenoma in one case2 and within the hyperplastic parathyroid tissue in the one case in which no adenoma was found.2 In all cases that reported laboratory data, the serum calcium level was increased, serum 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D was elevated or at the upper limits of normal, serum 25(OH) vitamin D was low and the serum PTH level was elevated. Most patients were women, and all were aged older than 55 years.

Table 1.

Sarcoid granulomas in the parathyroid gland, literature review.

| Case report | Age (years) | Sex | Race | Calcium level | 25(OH) vitamin D | 1,25(OH)2vitamin D | PTH level | Parathyroid adenoma present |

| Robinson et al1 | 56 | F | NS | Elevated | NS | NS | Elevated | Yes |

| Schweitzer et al2 | 74 74 |

F M |

Caucasian Caucasian |

Elevated Elevated |

NS NS |

NS NS |

Elevated Elevated |

Yes No |

| Taguchi et al3 | 55 | F | Japanese | Elevated | Low | NS | Elevated | Yes |

| Chaychi et al4 | 67 | M | Caucasian | Elevated | Low | High | Elevated | Yes |

| Balasanthiran et al5 | 70 | F | NS | Elevated | Low | NS | Normal | Yes |

| Present Case | 74 | F | Caucasian | Elevated | Low normal | High normal | Elevated | Yes |

F, female; M, male; NS, not specified in the article; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Vitamin D dysregulation is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in sarcoidosis, occurring in 5%–10% of patients.6 Such vitamin D dysregulation is the result of increased 1α hydroxylase activity in activated macrophages of the sarcoid granuloma, which converts 25(OH) vitamin D to 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, the active form of vitamin D.7 The resulting elevated 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D levels suppresses PTH levels.8 Similar to sarcoidosis-induced vitamin D dysregulation, primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with hypercalcaemia, low 25(OH) vitamin D levels and high 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D levels. However, the serum PTH is suppressed in sarcoidosis-associated vitamin D dysregulation, whereas it is elevated in primary hyperparathyroidism. Therefore, the workup of hypercalcaemia in patients with sarcoidosis should always include a measurement of PTH to distinguish these two entities. Hypercalcaemia due to sarcoidosis-induced vitamin D dysregulation is usually responsive to corticosteroid therapy, whereas hypercalcaemia secondary to primary hyperparathyroidism is managed by parathyroidectomy.

Malignancy is a common cause of severe hypercalcaemia in clinical practice. Most common malignancies associated with hypercalcaemia include lymphoma, squamous cell lung cancer and multiple myeloma. Although the pathophysiological basis of hypercalcaemia is different in different cancers, they are all associated with a low serum PTH level. Persistent hypercalcaemia can result in nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis and, even, renal failure. Evaluation of BMD by DEXA and detailed assessment of kidney function is necessary in patients with hypercalcaemia. It is crucial to emphasise that even in patients with sarcoidosis, hypercalcaemia should prompt a stepwise approach for the identification of the aetiology to avoid misdiagnosis and mismanagement.

The incidence and natural history of sarcoidosis involving the parathyroid gland are currently unknown. There are several postulations that could explain the association of parathyroid sarcoidosis involvement and primary hyperparathyroidism. First, it is possible that the adenoma or hyperplasia may develop secondary to chronic granulomatous inflammation. Second, the granulomas may represent reactive changes secondary to adenoma formation, similar to a sarcoidosis-like reaction adjacent to malignant tissue.9 Finally, it is also possible that these entities are independently present in the parathyroid gland without any causal association, as possibly only patients with sarcoidosis and evidence of parathyroid adenomas undergo parathyroid biopsy/resection.

Learning points.

Sarcoidosis of the parathyroid gland is almost always associated with hypercalcaemia and the presence of a parathyroid adenoma.

The clinician should be aware of this condition, as it can be confused with sarcoidosis-induced vitamin D dysregulation and delay a timely diagnosis and effective management.

Distinguishing these two entities requires vigilance and a detailed evaluation of vitamin D metabolism that should include obtaining a serum parathyroid hormone level.

Parathyroid adenoma is unresponsive to systemic steroid therapy.

More than one aetiology of hypercalcaemia might be present in a patient, and a stepwise approach is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis and mismanagement.

Footnotes

Contributors: BKS and MAJ were involved in direct patient care. BKS, SLB and LAF prepared the manuscript, and MAJ supervised and oversaw the preparation on the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Robinson RG, Kerwin DM, Tsou E. Parathyroid adenoma with coexistent sarcoid granulomas. A hypercalcemic patient. Arch Intern Med 1980;140:1547–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schweitzer VG, Thompson NW, Clark KA, et al. Sarcoidosis, hypercalcemia and primary hyperparathyroidism. The vicissitudes of diagnosis. Am J Surg 1981;142:499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taguchi K, Makimoto K, Nagai S, et al. Cystic parathyroid adenoma with coexistent sarcoid granulomas. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1987;243:392–4. 10.1007/BF00464649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chaychi L, Chaidarun S, Golding A, et al. Unusual recurrence of hypercalcemia due to concurrent parathyroid adenoma and parathyroid sarcoidosis with lymph node involvement. Endocr Pract 2010;16:463–7. 10.4158/EP09325.CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balasanthiran A, Sandler B, Amonoo-Kuofi K, et al. Sarcoid granulomas in the parathyroid gland - a case of dual pathology: hypercalcaemia due to a parathyroid adenoma and coexistent sarcoidosis with granulomas located within the parathyroid adenoma and thyroid gland. Endocr J 2010;57:603–7. 10.1507/endocrj.K10E-028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Conron M, Young C, Beynon HL. Calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis and its clinical implications. Rheumatology 2000;39:707–13. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.7.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell NH, Stern PH, Pantzer E, et al. Evidence that increased circulating 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D is the probable cause for abnormal calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis. J Clin Invest 1979;64:218–25. 10.1172/JCI109442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Papapoulos SE, Clemens TL, Fraher LJ, et al. 1, 25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in the pathogenesis of the hypercalcaemia of sarcoidosis. Lancet 1979;1:627–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)91076-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chopra A, Judson MA. How are cancer and connective tissue diseases related to sarcoidosis? Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21:517–24. 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]