Abstract

There is a well-established association between suicidal behavior and alcohol misuse. However, few studies have applied relevant theory and research findings in both the areas of alcohol and suicidal behavior to aid in the understanding of why these may be linked. The current study examined whether three variables (problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, and negative urgency) suggested by theory and previous findings in both areas of study help to account for the previously found association of suicidal ideation with drinking to cope and alcohol problems. Participants were 381 college women (60.4%) and men (39.6%) between the ages of 18 and 25 who were current drinkers and had a history of (at a minimum) passive suicidal ideation. Structural equation modeling was used to examine hypothesized associations among problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, drinking to cope (DTC), impulsivity in response to negative affect (i.e., negative urgency), severity of suicidal ideation, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems. Model results revealed that problem-solving skills deficits, avoidant coping, and negative urgency were each directly or indirectly associated with greater severity of suicidal ideation, DTC, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems. The results suggest that the positive association between suicidal ideation and DTC found in this and other studies may be accounted for by shared associations of these variables with problem-solving skills deficits, avoidant coping, and negative urgency. Increasing at risk students’ use of problem-solving skills may aid in reducing avoidance and negative urgency, which in turn may aid in reducing suicidal ideation, DTC, and alcohol misuse.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, depression, alcohol, coping skills, social problem solving

Acute episodes of alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders are positively associated with attempted and completed suicide (Cherpitel, Borges, & Wilcox, 2004; Hawton, Comabella, Haw, & Saunders, 2013; Hufford, 2001; Powell et al., 2001; Wilcox, Conner, & Caine, 2004). The association of suicidal ideation and attempts with alcohol is also demonstrated in college students, a population with high rates of suicidal ideation and attempts as well as alcohol use and problems (Blanco et al., 2008; Brener, Hassan, & Barrios, 1999; Gonzalez, Bradizza, & Collins, 2009; Gonzalez, 2012; Knight et al., 2002). However, research examining potential functional associations between these problems or that integrates theory and findings in both areas of study has been limited.

Social and operant learning theory-based motivational models suggest that for some individuals, alcohol use is motivated by attempts to regulate or avoid negative affect, contributing to a problematic reliance on alcohol to cope with negative affect (Abrams & Niaura, 1987; Catanzaro, Wasch, Kirsch, & Mearns, 2000; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1988; Stasiewicz & Maisto, 1993). Consistent with these models, depression is associated with greater alcohol problems among students and other populations, and both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies show that the relationship between depression and alcohol problems is in part due to the mediational role of drinking to cope (DTC) with negative affect (Gaher, Simons, Jacobs, Meyer, & Johnson-Jimenez, 2006; Gonzalez et al., 2009; Gonzalez, Reynolds, & Skewes, 2011; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2003; Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000; Kenney, Merrill, & Barnett, 2017; Peirce, Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1994; Schuckit, Smith, & Chacko, 2006). Research has also shown that DTC is a significant intervening variable in the association between severity of suicidal ideation and alcohol use and problems among underage college drinkers with a history of suicidal ideation (Gonzalez et al., 2009). While DTC may be one factor linking suicidal ideation with alcohol use and problems, theory and research in the areas of negative affect-related alcohol use and suicidal behavior suggest three other factors that may help to explain why individuals experiencing suicidal ideation may turn to DTC. These factors include avoidant coping, problem-solving skills deficits, and impulsivity.

Role of Problem-Solving and Coping-Skills Deficits

In motivational models of alcohol use, DTC is thought to be a learned behavior by individuals who lack more adaptive means of coping with negative affect (Catanzaro et al., 2000; Cooper et al., 1995), leading to a dependence on alcohol (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000). Adaptive or problem-focused coping, which is coping that is aimed at finding and implementing adaptive solutions to problems, has typically not been found to be associated with DTC or with alcohol use and problems (Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988; Evans & Dunn, 1995; Karwacki & Bradley, 1996; Park & Levenson, 2002). In contrast, the use of maladaptive avoidant coping is more consistently associated with DTC and alcohol problems (Britton, 2004; Cooper, Wood, Orcutt, & Albino, 2003; Evans & Dunn, 1995; Fromme & Rivet, 1994; Johnson & Pandina, 2000). Further, evidence suggests avoidant coping influences alcohol problems only indirectly through its effect on DTC (Cooper et al., 1988; Hasking, Lyvers, & Carlopio, 2011).

Similar to motivational models of alcohol use, cognitive behavioral models note the important role of deficits in problem-solving and adaptive coping skills in contributing to suicidal ideation and attempts (Reinecke, 2006). Research with college students and other populations has found that suicidal ideation and attempts are associated with a deficit in problem-solving skills (Chang, 1998; Clum & Febbraro, 1994; McAuliffe, Corcoran, Keeley, & Perry, 2003; Pollock & Williams, 2001; Pollock & Williams, 2004; Schotte & Clum, 1982), which are deliberate cognitive and behavioral activities to find, evaluate, and implement effective solutions to problems (D’Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 2002). Suicidal ideation and attempts are also associated with greater use of avoidant coping (Edwards & Holden, 2003; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, O’Brien, Klibert, Arata, & Bowers, 2006; Reinecke, Mark A., DuBois, & Schultz, 2001). However, problem-solving skills and avoidant coping have rarely been examined together or in relation to each other. It has been theorized that avoidant reactions to stressful life problems (i.e., avoidant coping) may stem from deficits in problem-solving skills (D’Zurilla & Chang, 1995; D’Zurilla et al., 2002). Consistent with this notion, randomized controlled trials with college students (Chinaveh, 2013) and women undergoing fertility treatment (Ghasemi et al., 2017) have shown significant decreases in avoidant coping and increases in approach coping strategies following problem-solving skills training.

Role of Impulsivity

Negative urgency — acting on behavioral impulses in response to negative affect without regard for consequences — is a facet of impulsivity that is particularly associated with alcohol problems (Magid & Colder, 2007; Verdejo-Garcia, Bechara, Recknor, & Perez-Garcia, 2007; Xiao et al., 2009) and is theorized to underlie the relationship between negative affect and alcohol problems (Anestis, Selby, & Joiner, 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2009), as well as to promote various risky behaviors in an attempt to quickly reduce negative affect (Anestis et al., 2007). It is an important construct in the study of suicidal behavior because it captures impulsivity in response to negative affect, which some suicide theorists suggest is the most likely connection between the established association of impulsivity and suicide attempts (Wenzel, Brown, & Beck, 2009). Negative urgency is associated with suicidal ideation and attempts (Anestis, Bagge, Tull, & Joiner, 2011; Glenn & Klonsky, 2010; Lynam, Miller, Miller, Bornovalova, & Lejuez, 2011) and both directly (Anestis et al., 2007; Settles, Cyders, & Smith, 2010) and indirectly (through its effect on DTC) predicts alcohol consequences (Cyders & Coskunpinar, 2010).

There is some evidence that impulsivity is associated with coping behavior, as populations high in impulsivity tend to be higher in avoidant coping and lower in adaptive coping (Cooper et al., 2003; Kruedelbach, McCormick, Schulz, & Grueneich, 1993; Nower, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2004). It has been suggested that negative urgency as a trait may interfere with the development of adaptive coping skills and lead to less use of adaptive coping strategies over time (Cyders & Smith, 2008). However, research has not examined psychosocial factors that may affect the various facets of impulsivity. This likely is due to impulsivity being conceptualized as a personality trait with a biological underpinning (Fischer, Smith, Spillane, & Cyders, 2005; Fischer & Smith, 2008), thus viewed as being cause rather than consequence and stable over time. However, there is research showing that some facets of impulsivity change significantly over the course of treatment for depression (Corruble & Guelfi, 1999; Corruble, Benyamina, Bayle, & Hardy, 2003) and substance abuse (Littlefield et al., 2015). Among individuals in substance abuse treatment, negative urgency, inhibitory control, and lack of planning improved moderately over the course of a 4-week treatment, while other facets of impulsivity showed little change (i.e., sensation seeking, lack of perseverance, lack of premeditation, and positive urgency; Littlefield et al., 2015). This suggests that some facets of impulsivity may be treatment malleable response tendencies.

Current Study

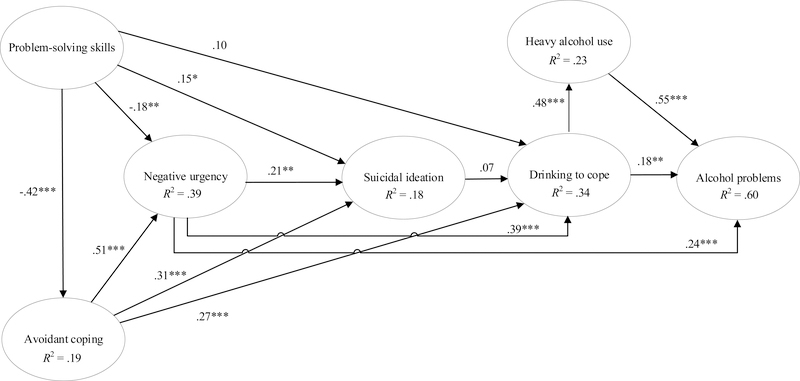

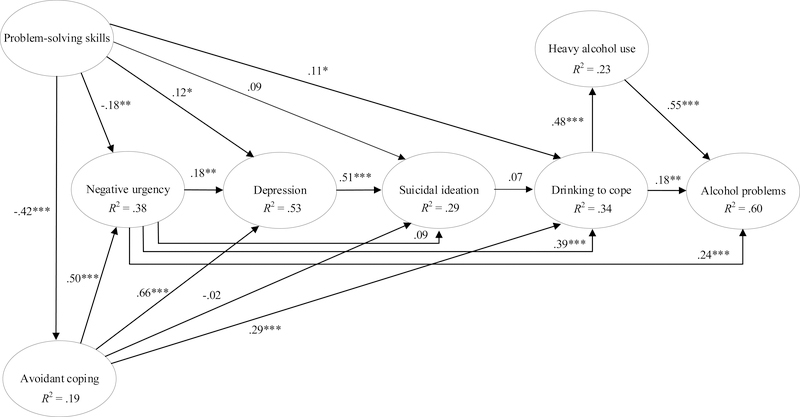

The current study examined whether problem-solving skills deficit, avoidant coping, and negative urgency help to account for the previously found association of suicidal ideation with DTC and alcohol problems (Gonzalez et al., 2009). Specifically, it was hypothesized that fewer problem-solving skills would be associated with greater use of avoidant coping, and that these both would be associated with greater negative urgency, suicidal ideation, and DTC (see Figure 1). Consistent with previous research, it also was hypothesized that negative urgency would directly be associated with DTC as well as alcohol problems (Cyders & Coskunpinar, 2010), and that DTC would be associated with greater alcohol use and consequences (Gonzalez et al., 2011) While the hypothesized relationships of suicidal ideation and DTC with other variables in the model were of primary interest, depression is an important variable to examine relative to the conceptual model given its strong association with suicidal ideation (Gonzalez et al., 2009; Konick & Gutierrez, 2005). Therefore, an additional model that included depression was also examined (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Model A. Standardized coefficients for the structural model are shown, as well as variance accounted (squared multiple correlation) for in each latent variable (R2). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Figure 2.

Model B. Standardized coefficients for the structural model are shown, as well as variance accounted for in each latent variable (R2). *p < .05. **p <.01.***p < .001.

Method

Participants

Participants were 381 emerging adult (18- to 25-year-old) female (60.4%, n = 230) and male (39.6% n = 151) drinkers with a history of, at a minimum, passive suicidal ideation (i.e., thoughts of being better off dead). Participants were recruited from two large, open enrollment universities in Alaska (campus A, n = 261; campus B, n = 120). Participants’ mean age was 21.4 years (SD = 2.1) and 87.1% were single (never married). The sample was 65.6% White/European American, 13.9% American Indian/Alaska Native (including mixed heritage), 10.8% multiethnic, 3.4% Asian American, 3.4% Latino, 1.6% Black/African American, and 1.3% “other.”

Procedures

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both universities where the study was conducted. Participants were recruited via e-mail solicitations directed to 18- to 25-year-old students through their university email; fliers posted on campus; and via advertisements in the school newspapers, websites, and radio stations. Advertisements directed potential participants to a webpage that described the study in general terms (e.g., “a study of college student lifestyle and mood”) and included a questionnaire with items that screened for study eligibility embedded among health and mood-related distractor items.

Eligibility criteria included: (1) having consumed at least four standard alcoholic drinks in the past month, (2) being a full- or part-time university student, (3) being between the ages of 18 and 25 years old, and (4) reporting a history of passive suicidal ideation (endorsement of a single item, “In the past, have you thought it would be better if you were not alive?”). This screening item represents a mild and passive form of suicidal ideation, and was chosen to be minimally distressing to individuals being screened online. This criterion was used to include students with a wide range of suicidal ideation severity. The relatively low level of alcohol consumption in the past month (at least 4 drinks) was used as an eligibility criterion to include students who demonstrate a wide range of drinking behavior and problems.

Those who met eligibility criteria were scheduled for a single in-person data collection session on their respective campus, where study materials were presented in random order on laptop computers. After data collection, all participants were given referral information for free or low-cost mental health services, as well as suicide/crisis hotline phone numbers (see Gonzalez & Neander, 2018 for a more detailed description of the safety protocol used in this study). Participants were compensated with a $50 Visa gift card or cash.

Measures

Problem-solving skills

The Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R; D’Zurilla et al., 2002) is a 52-item self-report measure of responses to problem-solving situations. Life problems are defined as something important and very bothersome to the respondent, for which they do not have an immediate solution or means of making it less bothersome. Items are rated from 0 (not at all true of me) to 4 (extremely true of me). The SPSI-R demonstrates good test-retest reliability, as well as good convergent and divergent validity with young adults (D’Zurilla et al., 2002). The 20-item rational problem solving (RPS) subscale score was used in this study to measure problem-solving skills. The RPS subscale measures engagement in active problem solving, including defining the problem, generating solutions, considering short- and long-term consequences of potential solutions, solution implementation, and evaluation of a solution’s effectiveness in resolving the problem.

Avoidant coping

The COPE (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989) is a 60-item self-report inventory that assesses coping strategies. Participants rate their typical responses to difficult or stressful events in their lives on a 4-point scale (1 = I usually don’t do this at all, 4 = I usually do this a lot). In college students, the COPE subscales demonstrate moderate test-retest reliability (Carver et al., 1989) and convergent validity (Clark, Bormann, Cropanzano, & James, 1995). Following the procedure used in previous coping research, it was initially planned to use three subscale mean scores from the COPE to represent forms of avoidant coping: denial, behavioral disengagement, and mental disengagement (Carver et al., 1989; Catanzaro & Laurent, 2004; Fromme & Rivet, 1994). However, the internal consistency of the mental disengagement subscale was quite low (coefficient alpha = .32) and therefore was not included in the analyses. In addition to subscales from the COPE, the SPSI-R avoidance style (AS) subscale was used as an indicator of avoidant coping in this study. The AS subscale includes seven items that measure avoiding thinking of or acting to solve problems.

Negative urgency

The UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale’s (Cyders et al., 2007; Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) 12-item negative urgency subscale was used in this study. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (1 = agree strongly, 4 = disagree strongly), with higher scores indicating greater impulsivity. This subscale demonstrates good differential and convergent validity (Settles et al., 2011; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005).

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. Items are rated from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II evidences high test-retest reliability as well as criterion and convergent validity among university students (Sprinkle et al., 2002).

Suicidal ideation

The Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ; Reynolds, 1991) is a 25-item self-report measure of suicidal thoughts and behavior experienced during the last month. Items are rated on a 7-point scale (0 = never had the thought, 6 = almost every day). Factor analysis with a college student sample has revealed three factors relating to the anticipated response of others (nine items); serious suicidal ideation, intent, and planning (10 items); and relatively mild suicidal ideation (six items; Reynolds, 1991). The ASIQ demonstrates high test-retest reliability and good convergent validity in college students (Gutierrez, Osman, Kopper, Barrios, & Bagge, 2000; Reynolds, 1991), as well as evidencing predictive validity for suicide attempts (Osman et al., 1999).

Drinking to cope (DTC)

Mean scores from three self-report scales were used to measure DTC: the Drinking Context Scale’s (DCS; O’Hare, 2001) three-item negative coping subscale, the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised’s (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994) five-item coping motives subscale, and Labouvie and Bates’s (2002) 13-item suppression (i.e., coping) reasons subscale. On the DCS, respondents rate each item based on the chances they would find themselves drinking excessively from 5 (extremely high) to 1 (extremely low) in the presented context. On the DMQ-R, respondents rate their relative frequency of consuming alcohol for various motives on a 4-point scale from 1 (never/almost never) to 4 (always/almost always). On Labouvie and Bates’s measure, respondents rate the importance of each reason for drinking item on a 3-point scale from 0 (not at all important) to 2 (very important). Each of these subscales has demonstrated good concurrent and/or convergent validity (Cooper et al., 1995; Labouvie & Bates, 2002; O’Hare, 2001; Stewart & Devine, 2000).

Heavy alcohol use

The Self-Administered Timeline Followback (S-TLFB; Collins, Kashdan, Koutsky, Morsheimer, & Vetter, 2008) is a self-report version of the 30-day TLFB (Sobell, Sobell, Klajner, & Pavan, 1986). In this study, the S-TLFB was used to quantify the number of days on which heavy drinking occurred (≥ 4 standard drinks for women, ≥ 5 standard drinks for men) in the past 30 days. Additionally, typical monthly frequency of heavy episodic drinking (≥ 4 standard drinks for women, ≥ 5 standard drinks for men on one occasion or sitting) in the past year was measured using items modified from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA) alcohol consumption question set (Gonzalez et al., 2011; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2003). For both the S-TLFB and this scale, participants were provided with a handout that defined and depicted a standard drink (e.g., 12 oz. beer, 5 oz. of wine, 8 to 9 oz. of malt liquor, or 1.5 oz. of 80-proof liquor).

Alcohol problems

The Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006) is a 48-item self-report inventory of problems associated with alcohol use, with items rated dichotomously as present or absent in the past year. This scale demonstrates high test-retest reliability, as well as good convergent, concurrent, and predictive validity with college students (Read et al., 2006; Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007).

Analyses

Structural equation modeling, using maximum likelihood estimation, was used to test the model presented in Figure 1 as well as a model that included depression (see Figure 2) using AMOS Version 25 (Arbuckle, 2017). A two-step modeling process was used; first the measurement model was verified and then the structural models (i.e., models of paths between latent variables) were examined (Kline, 2005). Model fit was assessed using the model chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), and standardized root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). The SRMR and RMSEA can be considered “badness of fit” indicators, with smaller scores desirable, while higher CFI scores indicate better model fit. Close model fit is suggested by a CFI > .90, a SRMR < .10, and a RMSEA ≤ .05 (Kline, 2005). In addition to evaluating model fit, the associations among the latent variables were evaluated by examining the path coefficients and indirect effects.

The avoidant coping latent variable had three indicators made up of the SPSI-R AS subscale as well as the COPE’s behavioral disengagement and denial subscales. The problem-solving skills latent variable was formed by parceling the rational problem solving subscale of the SPSI-R into three indicators using a balanced approach, while assigning any correlated residuals to the same parcel (Little, Rhemtulla, Gibson, & Schoemann, 2013). This method was used for all indicators formed by parceling. The suicidal ideation latent variable had three indicators corresponding to its factors (Reynolds, 1991). Depression was formed by parceling items from the BDI-II into three parcels, with the suicidality item omitted to avoid a potential confound with the latent suicidal ideation variable. Negative urgency items from the UPPS-P were parceled into three indicators. DTC had three indicators corresponding to subscale means of the DSC, the DMQ-R, and the Labouvie and Bates’s (2002) reasons for drinking subscale. Heavy alcohol use had two indicators, past 30-day frequency of heavy drinking days (HDD) and typical monthly frequency of heavy episodic drinking (HED) in the past year. The alcohol problems latent variable was formed by parceling YAACQ items into three indicators.

Prior to model testing, data were screened for outliers, non-normal response distributions, and missing data following the procedures outlined in Tabachnick and Fidell (2012). Participant responses were also screened for insufficient effort, as indicated by low personal correlations on measure items that were highly correlated in the sample (i.e., psychometric synonyms, r ≥ .60) and/or low personal reliability (i.e., individual response consistency within measures; DeSimone, Harms, & DeSimone, 2015). Of the 397 students who screened eligible and completed the protocol, 16 individuals were excluded from the study during data screening. Seven participants had markedly low correlations on the study’s psychometric synonyms, indicative of random or markedly careless responding; six were multivariate outliers; and three were missing alcohol use data. The alcohol consumption variables, the ASIQ subscales, and denial were positively skewed and square-root transformed. Age and gender were included as model covariates. Campus and race/ethnicity were considered as covariates; however, these variables were not significantly associated with the model variables and thus were not included in the models.

Results

Descriptive Information

The inclusion criterion of a history of passive suicidal ideation was effective in recruiting a sample with a wide range of suicidal ideation and behavior. The lifetime suicide attempt rate in the sample was 17.6% (n = 67). Mean total score on the ASIQ was 25.13 (SD = 19.50), with 65.6% (n = 250) reporting suicidal ideation in the past month based on ASIQ responses. Additionally, 24.7% (n = 94) were above the clinical cutoff (at or above 31) on the ASIQ, which identifies individuals who are actively thinking about suicide (Reynolds, 1991). Mean score on the BDI-II was 16.15 (SD = 10.13). Participants reported a mean of 4.43 (SD = 4.60) heavy drinking episodes on a typical month in the past year, and 3.13 (SD = 3.48) heavy drinking days in the past month. Mean number of alcohol consequences in the past year, as measured by the YAACQ, was 15.87 (SD = 10.10).

Measurement Model

First, the adequacy of the measurement model that included depression was evaluated, with fit indices suggesting close fit, χ2(202) = 315.07, p <.001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .04 [90% CI .03, .05, pclose = .992], SRMR = .03. Further, an examination of the parameter estimates, modification indices, and standardized residuals revealed there were no significant areas of localized model misfit. See Table 1 for indicator means, standard deviations, and factor loadings, and Table 2 for correlations among the latent variables.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistency, and Factor Loadings of Model Indicators

| Variables | M | SD | Internal consistency | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem solving skills | ||||

| Parcel 1 | 15.03 | 5.56 | .83 | .92 |

| Parcel 2 | 14.32 | 5.67 | .83 | .93 |

| Parcel 3 | 13.85 | 4.62 | .80 | .92 |

| Avoidant coping | ||||

| Deniala | 1.49 (1.20) | .60 (.23) | .76 | .57 |

| Behavioral disengagement | 1.65 | .62 | .79 | .80 |

| Avoidance style | 10.12 | 6.11 | .86 | .75 |

| Negative urgency | ||||

| Parcel 1 | 10.25 | 2.74 | .69 | .85 |

| Parcel 2 | 9.85 | 2.69 | .69 | .89 |

| Parcel 3 | 10.43 | 2.77 | .73 | .77 |

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

| Mild suicidal ideationa | 8.66 (2.72) | 6.42 (1.13) | .90 | .91 |

| Response of othersa | 8.77 (2.70) | 7.18 (1.22) | .87 | .89 |

| Serious suicidal ideationa | 7.70 (2.45) | 7.35 (1.31) | .92 | .91 |

| Depression | ||||

| Parcel 1 | 4.91 | 3.43 | .75 | .86 |

| Parcel 2 | 5.97 | 4.23 | .79 | .89 |

| Parcel 3 | 4.82 | 2.98 | .69 | .87 |

| Drinking to cope | ||||

| Negative coping | 2.16 | 1.01 | .87 | .75 |

| Suppression reasons | .56 | .45 | .90 | .90 |

| Coping motives | 2.13 | .90 | .82 | .89 |

| Heavy alcohol use | ||||

| Heavy drinking daysa | 3.13 (1.44) | 3.48 (1.02) | .80 | |

| Heavy episodic drinkinga | 4.43 (1.80) | 4.60 (1.09) | .91 | |

| Alcohol problems | ||||

| Parcel 1 | 7.12 | 3.96 | .84 | .85 |

| Parcel 2 | 4.82 | 3.57 | .83 | .87 |

| Parcel 3 | 3.93 | 3.54 | .83 | .88 |

Note. All factor loadings of indicators on their respective latent variables were significant (p < .001). Problem-solving skills parcels 1 and 2 were comprised of seven items, and parcel 3 was comprised of six items. Depression parcels 1 and 2 were each comprised of seven items, and parcel 3 was comprised of six items. Each negative urgency parcel was comprised of four items, and alcohol problems parcels each were comprised of 16 items. Specific items included in parcels are shown in supplemental Table 1.

This variable was square-root transformed prior to analyses. Mean and standard deviation shown are for the untransformed variables with the transformed values in parentheses.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Latent Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem-solving skills | — | ||||||

| 2. Avoidant coping | −.43*** | — | |||||

| 3. Negative urgency | −.39*** | .55*** | — | ||||

| 4. Suicidal ideation | −.06 | .39*** | .36*** | — | |||

| 5. Depression | −.23*** | .68*** | .52*** | .60*** | — | ||

| 6. Drinking to cope | −.17** | .46*** | .53*** | .31*** | .46*** | — | |

| 7. Heavy alcohol use | −.12* | .19** | .21*** | −.01 | .07 | .47*** | — |

| 8. Alcohol problems | −.11 | .37*** | .47*** | .12* | .26*** | .57*** | .69*** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Structural Model A

The hypothesized structural model presented in Figure 1 was close fitting, χ2(183) = 329.81, p <.001, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05 [90% CI .04, .05, pclose = .794], SRMR = .04. Most of the hypothesized direct associations among the variables in the model were found to be significant. Problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, and negative urgency were each significantly associated with suicidal ideation and DTC. The associations among these variables were both direct (see Figure 1 for the direct effects) and indirect (see Table 3 for indirect and total effects). Although the direct association of problem-solving skills with suicidal ideation was modest (β = .15, p = .010) and in the opposite direction to that hypothesized (i.e., a positive association), problem-solving skills also showed significant negative indirect effects with suicidal ideation (β = −.21, p =.001) and DTC (β = −.27, p = .001). Problem-solving skills also demonstrated significant negative direct (see Figure 1) and indirect effects through avoidant coping with negative urgency (β = −.21, p = .001), as well as significant negative indirect effects through avoidant coping and DTC with heavy alcohol use (β = −.08, p = .006) and alcohol problems (β = −.17, p = .001). Likewise, avoidant coping demonstrated positive direct effects with negative urgency, suicidal ideation, and DTC, as well as positive indirect effects through negative urgency with suicidal ideation (β = .10, p = .002) and with DTC (β = .23, p < .001). Avoidant coping was also positively indirectly associated with heavy alcohol use (β = .24, p = .001) through negative urgency and DTC. Negative urgency was positively directly associated with DTC and alcohol problems, and positively indirectly associated with heavy alcohol use (β = .19, p = .001) and problems (β = .18, p = .001) through DTC. Although suicidal ideation and DTC latent variables were significantly positively correlated (r = .31, p < .001; see Table 2) prior to parceling out their shared associations with problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, and negative urgency, the direct association between suicidal ideation and DTC was small and non-significant when these associations were accounted for.

Table 3.

Indirect Effects (Lower Diagonal) and Total Effects (Upper Diagonal) for Model A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem-solving skills | — | −.42** | −.39** | −.06 | −.17** | −.08** | −.17** |

| 2. Avoidant coping | — | — | .51** | .42** | .50** | .24** | .34** |

| 3. Negative urgency | −.21** | — | — | .21** | .41** | .19** | .42** |

| 4. Suicidal ideation | −.21** | .10** | — | — | .07 | .04 | .03 |

| 5. Drinking to cope | −.27** | .23** | .02 | — | — | .48** | .45** |

| 6. Heavy alcohol use | −.08** | .24** | .19** | .04 | — | — | .55** |

| 7. Alcohol problems | −.17** | .34** | .18** | .03 | .26** | — | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Structural Model B

The hypothesized structural model presented in Figure 2 was close fitting, χ2(243) = 444.29, p <.001, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05 [90% CI .04, .05, pclose = .782], SRMR = .05. Including depression in the model (see Figure 2), each of the prior reported direct relationships of the model variables with suicidal ideation were no longer significant, and instead, these variables were significantly associated with depression in place of suicidal ideation. Depression was strongly associated with suicidal ideation. Problem solving skills (β = −.14, p = .002), avoidant coping (β = .43, p = .001), and negative urgency (β = .09, p = .007) showed significant indirect effects with suicidal ideation through their associations with each other and depression (see Table 4 for indirect and total effects). Most indirect effects for depression were of a similar magnitude to that found for suicidal ideation in the previous model, except depression had a stronger negative indirect association with problems solving skills (β = −.35, p = .001) and direct association with avoidant coping (β = .66, p < .001) than did suicidal ideation. Although these associations were stronger for depression, no more variance was accounted for in DTC, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems when including depression in the model. These findings suggest that the associations of problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, and negative urgency with suicidal ideation in the prior model were accounted for by suicidal ideation’s association with depression.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects (Lower Diagonal) and Total Effects (Upper Diagonal) for Model B

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem-solving skills | — | −.42** | −.39*** | −.22** | −.06 | −.17** | −.08** | −.17** |

| 2. Avoidant coping | — | — | .50** | .75** | .41** | .51** | .24** | .35** |

| 3. Negative urgency | −.21** | — | — | .18* | .19** | .40** | .19*** | .42** |

| 4. Depression | −.35** | .09** | — | — | .51*** | .03 | .02 | .02 |

| 5. Suicidal ideation | −.14** | .43** | .09** | — | — | .07 | .03 | .03 |

| 6. Drinking to cope | −.28** | .22*** | .01 | .03 | — | — | .48** | .45** |

| 7. Heavy alcohol use | −.08** | .24** | .19*** | .02 | .03 | — | — | .55** |

| 8. Alcohol problems | −.17** | .35** | .18*** | .02 | .03 | .26** | — | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Regarding covariates in the model, women reported greater depression (β = .09, p = .036), negative urgency (β = .12, p = .009), and alcohol problems (β = .10, p = .013) than men. Older participants in this emerging adult sample reported greater negative urgency (β = .19, p < .001) and greater depression (β = .10, p = .026) than did younger participants.

Discussion

Model A results suggest that problem-solving skills deficits, the tendency to respond avoidantly to problems or distressing situations (i.e., avoidant coping), and impulsivity in response to negative affect (i.e., negative urgency), are each associated with greater severity of suicidal ideation, DTC, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems. Consistent with prior research (Gonzalez et al., 2009; Gonzalez & Hewell, 2012), there was a moderate positive association between suicidal ideation and DTC prior to parceling out their shared associations with problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, and negative urgency. However, in Model A, the direct association between suicidal ideation and DTC was small and non-significant when these associations were accounted for. This suggests that the association of suicidal ideation with DTC may be explained by their shared association with problem-solving skills deficits, avoidant coping, and negative urgency.

As hypothesized, less use of problem-solving skills was directly associated with greater avoidant coping and negative urgency. Consistent with prior research examining adaptive or problem-focused coping skills (Cooper et al., 1988; Evans & Dunn, 1995; Karwacki & Bradley, 1996; Park & Levenson, 2002), problem-solving skills were not directly associated with DTC. However, significant indirect associations were found between problem-solving skills deficits and greater DTC, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems. While motivational models of alcohol misuse have suggested that adaptive coping skills deficits contribute directly to a reliance on alcohol use to cope with negative affect (Cooper et al., 1995), the findings of this study suggest that the association of problem-solving skills with DTC and alcohol problems is indirect. Deficits in problem-solving skills potentially play a role in DTC by contributing to the likelihood of using maladaptive avoidant coping in response to distressing situations, as well as to greater negative urgency, and these in turn directly affect DTC.

While Model A may help to provide insights as to why suicidal ideation and DTC are related, Model B suggests that depression was playing a large role in the associations found among the variables in Model A. Consistent with previous research (Gonzalez et al., 2009; Konick & Gutierrez, 2005), depression was strongly associated with suicidal ideation. When included in the model, depression essentially took the place of suicidal ideation. Problem-solving skills, negative urgency, and avoidant coping showed direct and indirect associations with depression that were of a similar magnitude and direction as found in Model A for suicidal ideation. Problem-solving skills, avoidant coping, and negative urgency were no longer associated with suicidal ideation when depression was included in the model. However, like Model A, Model B suggests that these variables are potentially important treatment targets for student drinkers who are at risk for suicidal behavior. Addressing these issues could aid in reducing depression, which in turn could reduce suicidal ideation as well as alcohol problems.

This study hypothesized that problem-solving skill deficits would be associated with greater use of avoidant coping, consistent with this hypothesis these variables were moderately associated. While the current study found that using problem-solving skills was associated with less avoidance, it is important to note that the opposite also is true; avoidance makes the use of an approach strategy, such as the use of problem-solving skills, less likely. However, as has been demonstrated in research examining the effects of problem-solving skills training on coping skills, teaching a client what to do in response to distressing problems provides a means of both increasing this adaptive coping behavior and decreasing the use of maladaptive avoidant coping (Chinaveh, 2013; Ghasemi et al., 2017).

Consistent with the findings of this study, depression and suicidal ideation are often not found to be directly associated with greater alcohol use, despite their association with greater alcohol problems (e.g., Armeli, Conner, Cullum, & Tennen, 2010; Gaher et al., 2006; Gonzalez et al., 2011; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2007; Schuckit et al., 2007). The findings of this study may help to explain this pattern of associations. Specifically, the current findings suggest that depression and suicidal ideation are associated with factors that also are associated with DTC, which in turn was directly associated with greater heavy drinking and alcohol problems. One way that DTC may contribute to drinking problems above and amounts consumed is poor choices of when or where to drink because of a lack of more adaptive means of dealing with distress (e.g., Cooper et al., 1995; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005; Tragesser, Sher, Trull, & Park, 2007). Consistent with the notion of deficits contributing to DTC, in the current study the effects of problem-solving and avoidant coping on alcohol problems were indirect through their effect on DTC; however, negative urgency showed both this indirect effect and a direct effect on alcohol problems. As suggested for DTC, negative urgency may also contribute to poor choices of when and where to drink, exacerbating the potential for negative drinking consequences. Additionally, negative urgency along with poorer problem-solving skills and greater avoidance may lead to poor choices during and after drinking that make negative drinking consequences more likely. For example, engaging in rash behavior that escalates social conflicts associated with drinking rather than engaging in behavior to diffuse such conflicts, or responding to hangovers by missing work or school without considering the long-term consequences of this short-term solution to discomfort.

Several limitations should be considered. This study was cross-sectional, which does not allow inferences to be made regarding directionality of the associations, and a number of the hypothesized relationships explored are best conceptualized as reciprocal (e.g., use of problem-solving skills and avoidant coping). This study also examined factors that may influence negative urgency, which is frequently conceptualized as a personality trait (Fischer et al., 2005; Fischer & Smith, 2008). However, some facets of impulsivity, such as negative urgency, have been shown to change over the course of treatment (Corruble et al., 1999; Corruble et al., 2003; Littlefield et al., 2015). Further, the notion of examining factors that may affect traits that contribute to various forms of psychopathology is not novel, with recent work focusing on neuroticism as clinically malleable and a potentially fruitful psychosocial treatment target in its own right (Sauer-Zavala, Wilner, & Barlow, 2017). By studying factors that affect negative urgency, we may uncover treatment targets to address this generally problematic response tendency that affects a range of risky behaviors. It appears that problem-solving skills may provide a malleable treatment target for reducing impulsivity and severity of suicidal ideation (Eskin et al., 2008; Joiner et al., 2001). However, it is important to note that even when accounting for the effects of problem solving and avoidant coping, negative urgency was a unique predictor of DTC and alcohol problems. This suggests the need for additional strategies to address negative urgency.

Overall, consistent with previous research, emerging adult college students who suffer from depression and suicidal ideation are at risk for experiencing alcohol problems. One clinical implication of this study, not surprisingly, is that to address the suicide risk associated with suicidal ideation it is important to address depression. The findings together suggest that addressing response tendencies that may put students at risk for depression, suicidal ideation, and alcohol misuse may be particularly beneficial for addressing these related problems. Interventions aimed at increasing the use of problem-solving skills and decreasing avoidance may potentially help to reduce negative affect-related impulsivity, which in turn may help to reduce depression and thereby suicidal ideation, as well as DTC, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems among emerging adult drinkers who are at risk for suicidal behavior.

Supplementary Material

Public health significance.

There is a well-established association between suicidal ideation and attempts and alcohol misuse in college students and other populations. The results of this study suggest that interventions that increase problem-solving skills as well as decrease avoidant coping and impulsive behavior in response to negative affect may help to reduce suicidal ideation, drinking to cope with negative affect, and alcohol problems among college drinkers.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R21AA018135, awarded to Vivian M. Gonzalez. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funder had no role in this study other than providing financial support.

Footnotes

The author has no conflicts that may have influenced the research or interpretation of the findings.

References

- Abrams DB, & Niaura RS (1987). Social learning theory In Blane HT, & Leonard KE (Eds.), Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism (pp. 131–172). New York, NY: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Bagge CL, Tull MT, & Joiner TE (2011). Clarifying the role of emotion dysregulation in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in an undergraduate sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, & Joiner TE (2007). The role of urgency in maladaptive behaviors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 3018–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner TS, Cullum J, & Tennen H (2010). A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed.). Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu S, & Olfson M (2008). Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: Results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Hassan SS, & Barrios LC (1999). Suicidal ideation among college students in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 1004–1008. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton PC (2004). The relation of coping strategies to alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences in a college sample. Addiction Research & Theory, 12, 103–114. doi: 10.1080/16066350310001613062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, & Weintraub JK (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, & Laurent J (2004). Perceived family support, negative mood regulation expectancies, coping, and adolescent alcohol use: Evidence of mediation and moderation effects. Addictive Behaviors, 29, 1779–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, Wasch HH, Kirsch I, & Mearns J (2000). Coping related expectancies and dispositions as prospective predictors of coping responses and symptoms. Journal of Personality, 68, 757–788. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC (1998). Cultural differences, perfectionism, and suicidal risk in a college population: Does social problem solving still matter? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 237–254. doi:1018792709351 [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Borges GLG, & Wilcox HC (2004). Acute alcohol use and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 28S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinaveh M (2013). The effectiveness of problem-solving on coping skills and psychological adjustment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KK, Bormann CA, Cropanzano RS, & James K (1995). Validation evidence for three coping measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65, 434–455. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum GA, & Febbraro GAR (1994). Stress, social support, and problem-solving appraisal/skills: Prediction of suicide severity within a college sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 16, 69–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02229066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Kashdan TB, Koutsky JR, Morsheimer ET, & Vetter CJ (2008). A self-administered Timeline Followback to measure variations in underage drinkers’ alcohol intake and binge drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6, 117–128. doi: 10.1037/10403590.6.2.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, & Sheldon MS (2000). A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality, 68, 1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, & George WH (1988). Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 218–230. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Wood PK, Orcutt HK, & Albino A (2003). Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 390–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corruble E, Damy C, & Guelfi JD (1999). Impulsivity: A relevant dimension in depression regarding suicide attempts? Journal of Affective Disorders, 53, 211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00130-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corruble E, Benyamina A, Bayle F, Falissard B, & Hardy P (2003). Understanding impulsivity in severe depression? A psychometrical contribution. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 27, 829–833. doi: 10.1016/S02785846(03)00115-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, & Klinger E (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 168–180. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Coskunpinar A (2010). Is urgency emotionality? Separating urgent behaviors from effects of emotional experiences. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 807–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, & Peterson C (2007). Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment, 19, 107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone JA, Harms PD, DeSimone AJ (2015). Best practice recommendations for data screening. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, 171–181. doi: 10.1002/job.1962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, & Maydeu-Olivares A (2002). Social Problem-Solving InventoryRevised (SPSI-R): Technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla T, & Chang EC (1995). The relations between social problem solving and coping. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19, 547–562. doi: 10.1007/BF02230513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MJ, & Holden RR (2003). Coping, meaning in life, and suicidal manifestations: Examining gender differences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 1133–1150. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskin M, Ertekin K, & Demir H (2008). Efficacy of a problem-solving therapy for depression and suicide potential in adolescents and young adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DM, & Dunn NJ (1995). Alcohol expectancies, coping responses and self-efficacy judgments: A replication and extension of cooper et al.’s 1988 study in a college sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Spillane N, & Cyders MA (2005). Urgency: Individual differences in reaction to mood and implications for addictive behaviors In Clark AV (Ed.), The psychology of mood ( pp. 85–108). New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, & Smith GT (2008). Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, & Rivet K (1994). Young adults’ coping style as a predictor of their alcohol use and response to daily events. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 85–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01537143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaher RM, Simons JS, Jacobs GA, Meyer D, & Johnson-Jimenez E (2006). Coping motives and trait negative affect: Testing mediation and moderation models of alcohol problems among American Red Cross disaster workers who responded to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 1319–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi M, Kordi M, Asgharipour N, Esmaeili H, & Amirian M (2017). The effect of a positive reappraisal coping intervention and problem-solving skills training on coping strategies during waiting period of IUI treatment: An RCT. International Journal of Reproductive Biomedicine, 15(11), 687–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, & Klonsky ED (2010). A multimethod analysis of impulsivity in nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1, 67–75. doi: 10.1037/a0017427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM (2012). Association of solitary binge drinking and suicidal behavior among emerging adult college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 609–614. doi: 10.1037/a0026916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Bradizza CM, & Collins RL (2009). Drinking to cope as a statistical mediator in the relationship between suicidal ideation and alcohol outcomes among underage college drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 443–451. doi: 10.1037/a0015543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, & Hewell VM (2012). Suicidal ideation and drinking to cope among college binge drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 994–997. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, & Skewes MC (2011). Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19, 303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0022720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, & Neander LL (2018). Impulsivity as a mediator in the relationship between problem solving and suicidal ideation. Journal of Clinical Psychology. Advance online publication. 10.1002/jclp.22618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, & Bagge CL (2000). Suicide risk assessment in a college student population. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 403–413. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.4.403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasking P, Lyvers M, & Carlopio C (2011). The relationship between coping strategies, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and drinking behaviour. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Comabella CCI, Haw C, & Saunders K (2013). Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147, 17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, & Randall PK (2003). Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 159–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.1.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford MR (2001). Alcohol and suicidal behavior. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 797–811. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00070-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V, & Pandina RJ (2000). Alcohol problems among a community sample: Longitudinal influences of stress, coping, and gender. Substance use & Misuse, 35, 669–686. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Voelz ZR, & Rudd MD (2001). For suicidal young adults with comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders, problem-solving treatment may be better than treatment as usual. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(3), 278–282. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.32.3.278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karwacki SB, & Bradley JR (1996). Coping, drinking motives, goal attainment expectancies and family models in relation to alcohol use among college students. Journal of Drug Education, 26, 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, & Unrod M (2000). Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61, 332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Merrill JE, & Barnett NP (2017). Effects of depressive symptoms and coping motives on naturalistic trends in negative and positive alcohol-related consequences. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, & Schuckit MA (2002). Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konick LC, & Gutierrez PM (2005). Testing a model of suicide ideation in college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, 181–192. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.2.181.62875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruedelbach N, McCormick RA, Schulz SC, & Grueneich R (1993). Impulsivity, coping styles, and triggers for craving in substance abusers with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 7, 214–222. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1993.7.3.214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E, & Bates ME (2002). Reasons for alcohol use in young adulthood: Validation of a three-dimensional measure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, O’Brien N, Klibert J, Arata C, & Bowers D (2006). Gender specific associations among suicide proneness and coping strategies in college men and women In Landow MV (Ed.), College students: Mental health and coping strategies. ( pp. 247–260). Hauppauge, NY US: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, & Schoemann AM (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy neednt be one. Psychological Methods, 18, 285–300. doi: 10.1037/a0033266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Stevens AK, Cunningham S, Jones RE, King KM, Schumacher JA, & Coffey SF (2015). Stability and change in multi-method measures of impulsivity across residential addictions treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, & Cyders MA (2006). The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior (technical report). Purdue University, West Lafayette: [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Miller DJ, Miller JD, Bornovalova MA, & Lejuez CW (2011). Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: A test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 2, 151–160. doi: 10.1037/a0019978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, & Colder CR (2007). The UPPS impulsive behavior scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1927–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe C, Corcoran P, Keeley HS, & Perry IJ (2003). Risk of suicide ideation associated with problem-solving ability and attitudes toward suicidal behavior in university students. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 24, 160–167. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.24.4.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2003). Task Force on Recommended Questions of the National Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Recommended Sets of Alcohol Consumption Questions, October 15–16, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nower L, Derevensky JL, & Gupta R (2004). The relationship of impulsivity, sensation seeking, coping, and substance use in youth gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 49–55. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T (2001). The Drinking Context Scale: A confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 20, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00158-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Kopper BA, Linehan MM, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, & Bagge CL (1999). Validation of the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire and the Reasons for Living Inventory in an adult psychiatric inpatient sample. Psychological Assessment, 11, 115–123. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.2.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, & Levenson MR (2002). Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63, 486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham J, & Morgan-Lopez A (2007). College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, parental bonds, depression, and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 297–306. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, & Cooper ML (1994). Relationship of financial strain and psychosocial resources to alcohol use and abuse: The mediating role of negative affect and drinking motives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 291–308. doi: 10.2307/2137211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock LR, & Williams JMG (2004). Problem-solving in suicide attempters. Psychological Medicine, 34, 163–167. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock LR, & Williams JM (2001). Effective problem solving in suicide attempters depends on specific autobiographical recall. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31, 386–396. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.386.22041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KE, Kresnow M, Mercy JA, Potter LB, Swann AC, Frankowski RF, . . . Bayer TL (2001). Alcohol consumption and nearly lethal suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32, 30–41. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.30.24208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, & Colder CR (2006). Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, & Strong DR (2007). Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke M (2006). Problem solving: A conceptual approach to suicidality and psychotherapy In Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy (pp. 237–260). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke MA, DuBois DL, & Schultz TM (2001). Social problem solving, mood, and suicidality among inpatient adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 743–756. doi:1012971423547 [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM (1991). Adult Suicide Ideation Questionnaire: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer-Zavala S, Wilner JG, & Barlow DH (2017). Addressing neuroticism in psychological treatment. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8, 191198. doi: 10.1037/per0000224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte DE, & Clum GA (1982). Suicide ideation in a college population: A test of a model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 690–696. doi: 10.1037/0022006X.50.5.690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, & Chacko Y (2006). Evaluation of a depression-related model of alcohol problems in 430 probands from the San Diego prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 82, 194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Pierson J, Trim R, Nurnberger JI, . . . Hesselbrock V (2007). A comparison of factors associated with substance-induced versus independent depressions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Combs JL, Gunn RL, & Smith GT (2011). Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, doi: 10.1037/a0024948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, & Smith GT (2010). Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, & Christopher MS (2005). An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19, 326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, & Pavan D (1986). The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students’ recent drinking history: Utility for alcohol research. Addictive Behaviors, 11, 149–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinkle SD, Lurie D, Insko SL, Atkinson G, Jones GL, Logan AR, & Bissada NN (2002). Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 381–385. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.381 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz PR, & Maisto SA (1993). Two-factor avoidance theory: The role of negative affect in the maintenance of substance use and substance use disorder. Behavior Therapy, 24, 337–356. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80210-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, & Devine H (2000). Relations between personality and drinking motives in young people. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 495–511. doi: 10.1016/S01918869(99)00210-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, & Fidell L (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, & Park A (2007). Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: Cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15, 282–292. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, & Perez-Garcia M (2007). Negative emotion-driven impulsivity predicts substance dependence problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91, 213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel A, Brown GK, & Beck AT (2009). Cognitive therapy for suicidal patients with substance dependence disorders In Wenzel A, Brown GK & Beck AT (Eds.), Cognitive therapy for suicidal patients: Scientific and clinical applications. (pp. 283–310). Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/11862-013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, & Lynam DR (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, & Lynam DR (2009). Understanding the role of impulsivity and externalizing psychopathology in alcohol abuse. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, S(1), 69–79. doi: 10.1037/1949-2715.S.1.69 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, & Reynolds SK (2005). Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality, 19, 559–574. doi: 10.1002/per.556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Conner KR, & Caine ED (2004). Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An empirical review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 76, S19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Bechara A, Grenard LJ, Stacy WA, Palmer P, Wei Y, . . . Johnson CA (2009). Affective decision-making predictive of Chinese adolescent drinking behaviors. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 15, 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.