Abstract

Therapeutic embolization of blood vessels is a minimally invasive, catheter-based procedure performed with solid or liquid emboli to treat bleeding, vascular malformations, and vascular tumors. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) affects about half a million people per year. When unresectable, HCC is treated with embolization and local drug therapy by transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). For TACE, drug eluting beads (DC Bead®) may be used to occlude or reduce arterial blood supply and deliver chemotherapeutics locally to the tumor. Although this treatment has been shown to be safe and to improve patient survival, the procedure lacks imaging feedback regarding the location of embolic agent and drug coverage. To address this shortcoming, herein we report the synthesis and characterization of image-able drug eluting beads (iBeads) from the commercial DC Bead® product. Two different radiopaque beads were synthesized. In one approach, embolic beads were conjugated with 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl alcohol in the presence of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazol (CDI) to give iBead I. iBead II was synthesized with a similar approach but instead using a trimethylenediamine spacer and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid. Doxorubicin was loaded into the iBeads II using a previously reported method. Size and shape of iBeads were evaluated using an upright microscope and their conspicuity assessed using a clinical CT and micro-CT. Bland and Dox-loaded iBeads II visualized with both clinical CT and microCT. Under microCT, individual bland and Dox loaded beads had a mean attenuation of 7904±804 HU and 11873.96±706.12 HU, respectively. These iBeads have the potential to enhance image-guided TACE procedures by providing localization of embolic-particle and drug.

Keywords: Image-able Beads, TACE, HCC, DC/LC Bead, CT, Image-guided drug delivery

Introduction

Embolization is a minimally invasive, catheter-based procedure used to mechanically occlude blood vessels feeding a tumor or other target tissue to obtain therapeutic benefit [1, 2]. There are numerous pathologies that can be treated with embolization therapy, including bleeding [3–6], vascular malformations [7–12], and renal and hepatic tumors (both benign and malignant) [13–15]. Embolizing agents rely on mechanical obstruction to occlude vessels and the choice of a given therapy depends on the material properties and the desired clinical outcomes.

The first embolic agent in clinical use was autologous blood clots which were readily available and biocompatible [16], however, quick lysis of the clot limited the durability of the occlusion and utility. There are currently numerous types of embolic agents available including coils (pushable, injectable or detachable), solid synthetic polymers in the form of particles and microspheres (e.g., PVA hydrogels, trisacryl gelatin (TGA), poly(d-l-lactide), polymethylmethacrylate-based (PMMA) hydrogels), natural polymers (e.g., gelatin sponge, wax, starch, alginate and albumin microspheres) and liquids (e.g., cyanoacrylate glue, alcohol, ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer solutions) [16–25]. PVA, TGA, and PMMA microspheres are symmetrical, smooth and available in precisely calibrated size ranges [12, 19, 26–29]. PVA microspheres with sulfonate groups (DC Bead®) or sodium acrylate groups (HepaSphere® and Tandem®), respectively, are commonly used as drug carriers for chemoembolization to treat patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [30–32] and generically known as drug-eluting beads (DEBs).

HCC affects approximately 500,000 people worldwide, every year [33]. It is the second most common cause of cancer mortality [34]. The curative options that are currently available in clinics depend upon the stage of the disease. For example, surgical resections, liver transplant, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and vascular occlusion followed by RFA are options for early stage tumors and yield improved survival [33, 35–42]. When these options fail, transarterial embolization (TAE), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE; i.e., infusion of a chemotherapeutic followed by embolization), or the use of drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (DEB-TACE) [35, 43–46] are typical choices for palliative treatment [33]. Since the early 1970s, TAE and later TACE have become common clinical practice [1, 27, 33, 44, 47–62] and have improved the survival of patients with unresectable HCC [44, 53–55]. For instance, Yamada, et al. reported TAE with gelatin foam treatment for 120 unresectable hepatoma patients resulted in a cumulative one-year survival rate of 44% compared to 7% with conventional chemotherapy alone [63]. Similarly, Konno et al., in the early 1980s, introduced anticancer drug (SMANCS) in combination with Ethiodol® as image-guided TACE, which resulted in 10–99% tumor size reduction in 90% of patients with unresectable HCC [64]. Recently, uniformly sized microspheres with high drug loading capacity have emerged in the clinic as DEBs. These microspheres can be used in bland embolotherapy or more commonly loaded with chemotherapeutics to create a drug delivery device [31, 32, 59, 65–69]. For example, DEBs can simultaneously occlude arterial blood supply and deliver chemotherapeutics locally to the tumor (DEB-TACE) [56, 59, 61, 67, 68, 70, 71] providing theoretical benefit in limiting recurrence or time to tumor progression. One major drawback, however, with the current therapies is the lack of imaging feedback regarding the embolic bead location and drug coverage. Such information could inform and optimize therapy. To address this shortcoming, herein we report the synthesis and characterization of image-able drug eluting beads (iBeads) for real-time localization of embolic particles and drug during DEB-TACE.

The embolic particles used in this work are based upon sulfonate-modified PVA microspheres (DC Bead®) which have been used clinically as embolization devices for the treatment of hypervascular lesions and vascular malformations [57]. Chemically, these PVA microspheres contain abundant chemically modifiable and reactive alcohol groups. Some of the free alcohol groups of the PVA chains have been modified to attach sulfonic acid bearing moieties and are used to sequester positively charged drugs (e.g., doxorubicin, irinotecan, topotecan) [58, 72–74]. In this study, a portion of the hydroxyl groups of the PVA chain was modified with a radio-dense species to make the microsphere detectable by X-ray.

Materials and Methods

Materials

DC Bead® intermediate (Acrylamido Polyvinyl Alcohol-co-Acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonate microspheres, dried to a free-flowing powder and untainted) was obtained from Biocompatibles UK Ltd, a BTG International group company, Camberley, UK. Anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 1,1′-Carbonyldiimidazol (CDI), 2,3,5-Triiodobenzyl alcohol, 2,3,5-Triiodobenzoic acid, N,N′-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt), 4-(Dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP), Trimethylenediamine, Triethylamine (Et3N), and anhydrous Dichloromethane (DCM) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Doxorubicin (Dox) was obtained from Bedford Laboratories® (Bedford, OH). De-ionized water (DI water) was obtained from in house filtration system (Hydro Inc. Rockville, MD).

General methods

Evaluation of iBeads with microscopy

The size and appearance of beads during various steps of synthesis and Dox loading were examined and imaged in a chamber slide (Electron Microscopy Sciences; ~150 ul bead and DI water suspension). Bright field images were acquired with a 5× objective on an upright microscope (Zeiss Axioimager M1, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a color CCD camera (AxioVision, Zeiss).

Phantom preparation

In order to assess the radiopacity, beads were suspended in an agarose matrix at bead concentrations (sediment bead volume percent) that is relevant for in vivo applications. Bead containing agarose phantoms (0.5% w/v) with various concentrations (sedimented bead volume percent ranging from 0, 3.1, 6.2 and 12.5%) were prepared by adding a 1% agarose (w/v, in DI water) solution (at 55 °C) to an equal volume of bead suspension in DI water. The solutions were mixed while allowing the agarose to slowly gel (over ice), resulting in a homogeneous distribution of beads. [Note: The bead volume percent is sedimented bead volume due to gravity alone and does not account for aqueous solution between the packed beads or altered bead packing efficiency].

In vitro evaluation of radiopacity of iBeads with clinical and Micro CT

Clinical CT

Clinical CT imaging and analysis of iBead containing phantoms was performed on a 256 Slice CT (Philips, Andover, MA) with the following settings to determine the attenuation: 465 mAs tube current, 80 keV tube voltage, 1 mm slice thickness, 0.5mm overlap. The average attenuation of an 80 mm2 rectangular region in the middle slice of a given phantom was measured using OsiriX Software (V.5.02 64-bit).

MicroCT

MicroCT imaging and analysis of iBead containing phantoms was performed with a SkyScan 1172 high-resolution micro-CT (SkyScan, Konitch, BE) to evaluate the radiopacity of each individual bead, as well as, intra-bead distribution of iodine. The radiopaque microspheres were imaged at 5 μm resolution, 78 kV, 127 micro-Amps, using a 0.5 mm Aluminum filter. The average attenuation of individual beads was measured and reported as the mean and standard error (n=10).

Doxorubicin loading into iBeads and elution

iBeads were loaded with Doxorubicin (Dox) according to previously reported method [57, 58]. Briefly, 250 μl of thoroughly washed iBeads was immersed into 0.5 ml of Dox (20 mg/ml DI water) solution and shaken for 3 hours at room temperature. The Dox-loaded iBeads were used for subsequent experiments. Dox elution kinetics from iodinated beads (100–300μm and 300–500μm) were measured with a previously reported technique [58].

Experimental procedures

Method I: Conjugation of 2,3,5-Triiodobenzyl alcohol on to DC Beads (iBead I)

After washing the beads (1) (200 mg) with DMSO (3X 5 ml), the beads were allowed to swell in DMSO (20 ml) for 30 minutes at 50 °C. A portion of the beads hydroxyl group were activated by stirring the suspended beads with CDI (800 mg) (CDI: OH =~1.2:1) in the presence of catalytic amount of triethylamine (0.12 equivalent) at 50 °C for 24 hours. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and washed quickly with a cocktail of DMSO and DCM (1:1) and finally with DMSO alone. The washed beads were immediately transferred into a reaction flask containing a solution of 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl alcohol (971.7 mg) in DMSO (10 ml) and stirred for 24 hours at 50 °C (Scheme 1). The resulting product cooled to room temperature and was washed thoroughly with DMSO: DCM (1:1), followed by DMSO alone. Finally, the DMSO was exchanged with DI water (under continuous agitation) and the image-able beads thoroughly washed with saline and DI water consecutively. The clean beads (iBead I) were suspended in DI water until further analysis.

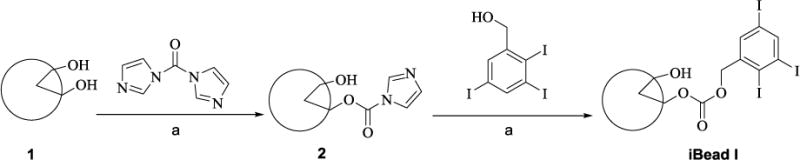

Scheme 1.

Mild activation of beads (1) with CDI and conjugation with 2,3,5-Triiodobenzyl alcohol. a) DMSO and DIEA, t=50 °C

Method II: Conjugation of 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid on to DC Beads through trimethylenediamine spacer

Methods II a: Grafting a spacer on to the DC Beads (4)

The beads were activated as described in method I above (200 mg of beads and 1.3 g of CDI) and reacted with excess 1,3-diaminopropane at 50 °C for 24 hours (Scheme 2). The reaction mixture was cooled and washed thoroughly as mentioned in method I to give the intermediate (4). Conjugation of the trimethylenediamine was confirmed by the Kaiser test [75].

Scheme 2.

Grafting the trimethylenediamine onto CDI activated beads (2) and conjugation of 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid, a) DMSO and DIEA, t=50 °C, b) DMSO, DIC, HOBt and DMAP or c) DMSO and CDI.

Methods II b: Conjugation of 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid with trimethylenediamine grafted beads (iBead II)

A solution of 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (2.4 g) in DMSO (20 ml) was activated with DIC (604.5 mg), HOBt (634.2 mg) and DMAP (586.4 mg) for 30 minutes at room temperature and the trimethylenediamine grafted beads (4) were added (Scheme 3). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 24 hrs. After cooling, the beads (iBead II) were thoroughly washed as described in method I. Alternatively, iBead II was synthesized first by activating the 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) with CDI as follows: 40 g of 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) was dissolved in 100 ml of anhydrous DMSO. The compound was activated by adding 13 g of CDI powder under magnetic stirring. The solution gradually became turbid and viscous after about 30 to 60 min. The mixture was then added into the trimethylenediamine grafted bead suspension in 100 ml of DMSO. The suspension was stirred at 50 °C, over 24 hr and was protected from light. The beads were washed with diethyl ether and DMSO mixture, then by deionized water.

Results

Synthesis and radiopacity

Method I

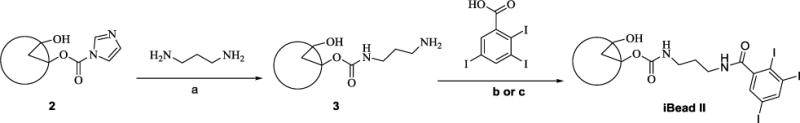

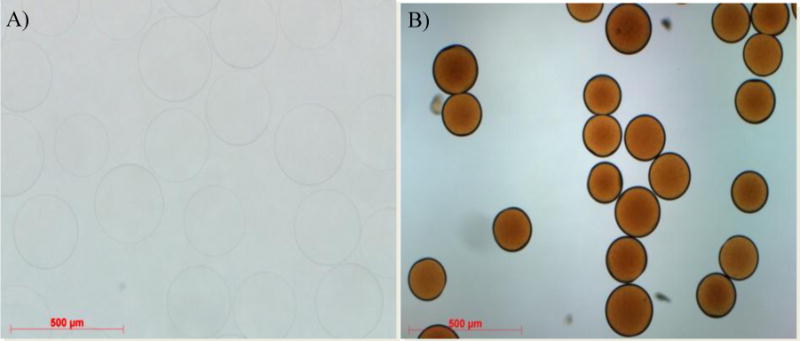

The beads were successfully activated with CDI under very mild conditions and conjugated with 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl alcohol (Scheme 1). Microscopic image comparison of raw and 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl alcohol conjugated beads (iBeads) revealed that the bead size was slightly reduced (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Size and appreance comprison of (A) raw bead and (B) iBead II under light micoroscopy.

Note: conjugation of 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl acid reduces the size and changes the appearance of the beads.

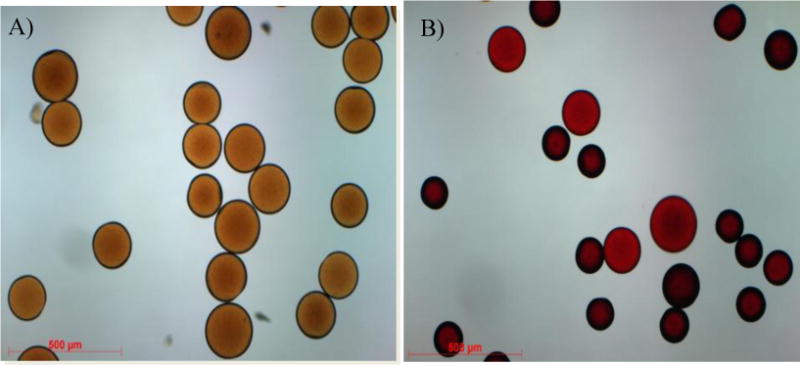

The 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl alcohol conjugated bead radiopacity was assessed both in clinical and microCT. With clinical CT, visualization is based on radiopacity of the beads in an agarose phantom per a given bead volume. A 3.1% packed bead volume showed a mean attenuation of 26±15 HU and increased to 41±16 HU and 74±25 HU as the packed bead volume increased to 6.2 and 12.5 %, respectively. With micro CT, individual beads had a mean attenuation of 619.96 ± 605.08 HU (n= 10).

Method II a

Trimethylenediamine was successfully grafted onto PVA beads as confirmed with Kaiser Test.

Method II b

The 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid was conjugated on the beads (iBead II) as confirmed by the disappearance of the bluish color upon performing the Kaiser Test. Alternatively, the reaction progress was monitored with HPLC by measuring the residual diamine in the reaction mixture after converting into N-(3-aminopropyl)-2-phenylacetamide with benzoyl chloride. Trimethylenediamine concentration gradually decreased over a period of 15 hours.

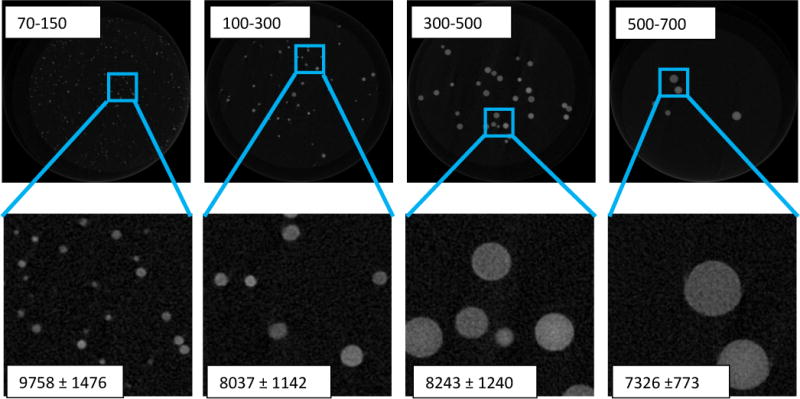

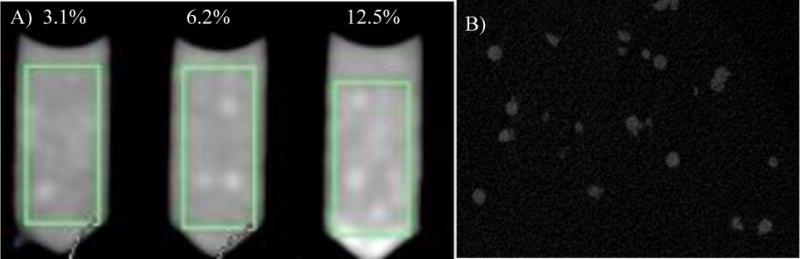

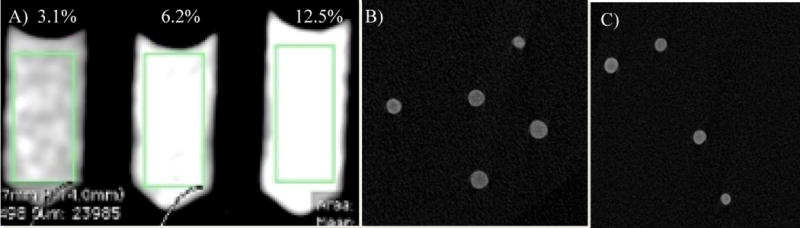

Clinical and microCT

The radiopacity was assessed with both clinical and micro CT. With the clinical CT, visualization is based on radiopacity of the beads per a given bead volume. A 3.1% packed bead volume showed a mean radiopacity of 129±33 HU and increased to 269±53 HU and 444±83 HU as the (iBead II) packed bead volume increased to 6.2 and 12.5 %, respectively. Using micro CT, individual bland and Dox loaded beads showed a mean attenuation of 7903±804 HU and 11873.96 ± 706.12, respectively (n= 10). Different bead size showed different iodine content and attenuation under microCT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Solid content, iodine content and μCT attenuation of iBeads II with different sizes

| Bead size (μm) | Solid content of hydrated beads (%) | Iodine content of dry beads (%) | MicroCT Attenuation (HU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70–150 | 27.2 | 41.9 | 9758 ± 1476 |

| 100–300 | 24.8 | 44.3 | 8037 ± 1142 |

| 300–500 | 23.7 | 45.1 | 8243 ± 1240 |

| 500–700 | 23.0 | 45.6 | 7326 ± 773 |

Microscopic comparison of raw beads (Figure 1A) and beads yielded from Method II b (Figure 3A) and thereafter Dox-loaded (Figure 3B) suggests that the conjugated hydrophobic moiety (phenyl group) results in a decreased bead size.

Figure 3.

Size comprison of raw (A) and Dox loaded (B) iBead II under Light microscopy. Note: Dox loading reduces the size of the beads.

Doxorubicin loading and elution

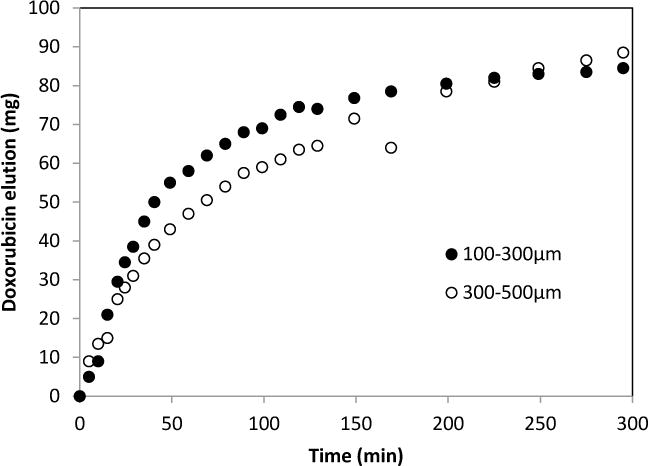

The bright red colored Dox solution was depleted within 3 hours of incubating with the radiopaque beads giving reddish beads with a Dox concentration of 40–80 mg/ml of beads similar to previously published for the raw beads [57, 58]. Dox elution profiles for iodinated beads with two different size populations (100–300 μ and 300–500 μ) and the smaller sized beads (100–300 μm) exhibited slightly more release as previously reported (Figure 6) [58].

Figure 6.

Doxorubicin elution from iodinated beads (100–300μm and 300–500μm).

Discussion

In this study, we present a successful methodology for the synthesis of radiopaque PVA based microspheres (iBeads). The radiopacity of the microspheres was confirmed both by clinical CT and MicroCT. The hydroxyl functional group of the PVA microspheres were mildly activated with CDI and coupled with either 2,3,5-triiodobenzyl alcohol or trimethylenediamine. Diamine conjugated beads were iodinated with 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (iBead II, Scheme 2) under both DIC and CDI conditions. The diamine was used as spacer between the PVA bead hydroxyl group and the conjugating 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid. The completeness of the conjugation was monitored by the Ninhydrin test as well as by elemental analysis for iodine content. Under both conditions, on average the iodine content of iodinated beads achieved 45.6% in dried state according to elemental analysis results. Direct conjugation of the triiodobenzyl alcohol on the activated beads resulted in low conspicuity compared to the triiodobenzoic acid which is conjugated through a trimethylenediamine spacer. The spacer may provide less steric hindrance between the bulky activating reagent (carbonylimidazole) and the triiodobenzoic acid so that more trimethylenediamine spacer reacts with the activated bead thereby providing a suitable environment for more triiodobenzoic acid to conjugate to the beads. Therefore, the individual radiopaque beads made of triiodobenzoic acid through a trimethylenediamine spacer had ~13 times greater attenuation under microCT than radiopaque beads made from the corresponding benzyl alcohol.

To examine the effect of bead size on iodine content and attenuation, the beads were sieved into different sizes (Table 1 & Figure 5) and were tested for solid content, iodine content and microCT attenuation, respectively. Although the iodine content in dry beads decreased with decreasing bead size, the attenuation was greater due to high density of the smaller bead size. Overall, the size of the iBead was smaller than the raw beads due to the hydrophobicity of the triiodobenzoic moiety which reduces the interaction of water molecules with the iBead [76].

Figure 5.

Comparison of iodinated bead size with their attenuation. The 70–150 μm beads have high attenuation than all other bead sizes (p<0.05)

Ideally, a chemoembolization agent is capable of providing occlusion of target vessels, high capacity drug loading, selective delivery of the drug to the tumor, and real-time imaging feedback of the embolic particle and drug location with 2D and 3D X-ray imaging [77, 78]. Since all clinically available embolic agents are radiolucent, complications like non-target embolization may occur undetected with the embolic agent alone. For this reason, chemoembolization procedures currently rely on the injection of a mixture of the embolizing agent with X-ray contrast medium [79, 80]. However, due to inadequate dispersion of the embolic material in the contrast media, the liquid media can traverse to the distal blood vessels more so than the embolic materials and as a result the fluoroscopic feedback this soluble contrast material provides misleading information about the location of the embolic material [81]. Instead, if the chemoembolic material has X-ray contrast property, the localization of embolic during and post embolization can be monitored and assessed in real-time with X-ray techniques. Such radiopaque embolic materials have been reported in the literature [6, 77, 78, 82–88], however, usually without drug loading capability. Recently, radiopaque beads and radiopaque Dox-eluting beads by mixing iodinated oil (Lipiodol®) with lyophilized PVA hydrogel beads were reported by our team and their use to chemoembolize swine liver and kidney was demonstrated [56, 70]. However, due to the lack of off-the-shelf availability, this approach might have limited clinical use.

In summary, we report the synthesis of iBeads based on a commercial embolization microsphere (DC Bead) after mild activation of the bead with CDI and conjugating the activated bead with 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid using 1,3-diaminopropane as a spacer to alleviate steric hindrance. This radiopaque bead may be visualized under clinical CT and can load a similar level of Dox as the bland beads. It may be noted however, that the Dox loading capability is highly compromised when this radiopaque bead is subjected to high sterilization temperature. We speculate that the high sterilization temperature may cause the hydrophobic moiety to orient itself in such a way that to obscure the sulfonate group responsible for driving Dox into the bead. Therefore, alternative chemistry or sterilization technique is required to solve this problem.

Conclusion

Radiopaque drug-eluting beads were successfully synthesized by direct chemical conjugation of a radio-dense triiodobenzyl species on the commercial bead. These image-able embolic beads are visible under clinical imaging conditions which enable real-time feedback of bead location and drug localization during and after DEB-TACE.

Figure 2.

Clinical CT (A) and Micro CT images (B) of iBead I

Figure 4.

A) Clinical CT image of bland iBeads II (the green rectangle shows the measured area, 0.8 cm2), B) Micro CT images of bland and Dox loaded (C) iBeads II. For micro CT, 3.1%, 6.2% and 12.5% (v/v) iBeads II pack phantom was used.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Center for Interventional Oncology in the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH and Biocompatibles UK Ltd, a BTG International group company have a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. C.G.J. was supported by the Imaging Sciences Training Program of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Belhu Metaferia, for his advice and useful discussions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Ayele H. Negussie, Carmen Gacchina Johnson, Gert Storm, Karun V. Sharma and Bradford J. Wood do not have any forms of conflicts of interest. The mention of commercial products, their source, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the National Institutes of Health. The authors alone are responsible for the content and opinions of the paper. NIH and Biocompatibles UK Ltd, a BTG International group company have a cooperative research and development agreement.

Contributor Information

Ayele H. Negussie, Email: negussiea@mail.nih.gov.

Matthew R. Dreher, Email: matthew.dreher@gmail.com.

Carmen Gacchina Johnson, Email: carmengacchina@gmail.com.

Yiqing Tang, Email: Yiqing.Tang@btgplc.com.

Andrew L. Lewis, Email: Andrew.Lewis@btgplc.com.

Gert Storm, Email: G.Storm@uu.nl.

Karun V. Sharma, Email: KVSharma@childrensnational.org.

Bradford J. Wood, Email: bwood@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Chuang VP, Wallace S. CURRENT STATUS OF TRANSCATHETER MANAGEMENT OF NEOPLASMS. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 1980;3(4):256–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02552737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loffroy R, et al. Endovascular Therapeutic Embolisation: An Overview of Occluding Agents and their Effects on Embolised Tissues. Current Vascular Pharmacology. 2009;7(2):250–263. doi: 10.2174/157016109787455617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosch J, Antonovi R, Dotter CT. SELECTIVE VASOCONSTRICTOR INFUSION IN MANAGEMENT OF ARTERIO-CAPILLARY GASTROINTESTINAL HEMORRHAGE. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1972;116(2):279–&. doi: 10.2214/ajr.116.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prochask Jm, Flye MW, Johnsrud Is. LEFT GASTRIC ARTERY EMBOLIZATION FOR CONTROL OF GASTRIC BLEEDING - COMPLICATION. Radiology. 1973;107(3):521–522. doi: 10.1148/107.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum S, Nusbaum M. CONTROL OF GASTROINTESTINAL HEMORRHAGE BY SELECTIVE MESENTERIC ARTERIAL INFUSION OF VASOPRESSIN. Radiology. 1971;98(3):497–&. doi: 10.1148/98.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartling SH, et al. First Multimodal Embolization Particles Visible on X-ray/Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Investigative Radiology. 2011;46(3):178–186. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318205af53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newton TH, Adams JE. ANGIOGRAPHIC DEMONSTRATION AND NONSURGICAL EMBOLIZATION OF SPINAL CORD ANGIOMA. Radiology. 1968;91(5):873–&. doi: 10.1148/91.5.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luessenh Aj, et al. CLINICAL EVALUATION OF ARTIFICIAL EMBOLIZATION IN MANAGEMENT OF LARGE CEREBRAL ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATIONS. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1965;23(4):400–&. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang SD, et al. Multimodality treatment of giant intracranial arteriovenous malformations (Reprinted from Archival article vol 53, pg 1, 2003) Neurosurgery. 2007;61(1):432–442. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000279235.88943.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luessenhop AJ, Mujica PH. EMBOLIZATION OF SEGMENTS OF THE CIRCLE OF WILLIS AND ADJACENT BRANCHES FOR MANAGEMENT OF CERTAIN INOPERABLE CEREBRAL ARTERIOVENOUS-MALFORMATIONS. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1981;54(5):573–582. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.5.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doppman JL, Dichiro G, Ommaya AK. PERCUTANEOUS EMBOLIZATION OF SPINAL CORD ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATIONS. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1971;34(1):48–&. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.34.1.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaujeux R, et al. Trisacryl gelatin microspheres for therapeutic embolization .2. Preliminary clinical evaluation in tumors and arteriovenous malformations. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1996;17(3):541–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rand T, et al. Arterial embolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with use of microspheres, lipiodol, and cyanoacrylate. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2005;28(3):313–318. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0153-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshburn PB, Matthews ML, Hurst BS. Uterine artery embolization as a treatment option for uterine myomas. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2006;33(1):125–+. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manelfe C, et al. TRANSFEMORAL CATHETER EMBOLIZATION IN INTRACRANIAL MENINGIOMAS. Revue Neurologique. 1973;128(5):339–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krysl J, Kumpe DA. Embolization agents: A review. Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2000;3(3):4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaidya S, Tozer KR, Chen J. An Overview of Embolic Agents. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25:12. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirchhoff TD, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization using degradable starch microspheres and iodized oil in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation of tumor response, toxicity, and survival. Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International. 2007;6(3):259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurent A, et al. Trisacryl gelatin microspheres for therapeutic embolization .1. Development and in vitro evaluation. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1996;17(3):533–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stampfl S, et al. Biocompatibility and recanalization characteristics of hydrogel microspheres with Polyzene-F as polymer coating. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2008;31(4):799–806. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao VRK, et al. HYDROLYZED MICROSPHERES FROM CROSS-LINKED POLYMETHYL METHACRYLATE (HYDROGEL) - A NEW EMBOLIC MATERIAL FOR INTERVENTIONAL NEURORADIOLOGY. Journal of Neuroradiology. 1991;18(1):61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayakrishnan A, et al. HYDROGEL MICROSPHERES FROM CROSSLINKED POLY(METHYL METHACRYLATE) - SYNTHESIS AND BIOCOMPATIBILITY STUDIES. Bulletin of Materials Science. 1989;12(1):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducmauger A, Benoit JP, Puisieux F. PREPARATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF CROSS-LINKED HUMAN-SERUM ALBUMIN MICROCAPSULES CONTAINING 5-FLUOROURACIL. Pharmaceutica Acta Helvetiae. 1986;61(4):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benita S, Zouai O, Benoit JP. 5-FLUOROURACIL - CARNAUBA WAX MICROSPHERES FOR CHEMOEMBOLIZATION - AN INVITRO EVALUATION. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1986;75(9):847–851. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600750905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spenlehauer G, Veillard M, Benoit JP. FORMATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF CISPLATIN LOADED POLY(D,L-LACTIDE) MICROSPHERES FOR CHEMOEMBOLIZATION. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1986;75(8):750–755. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600750805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodiek SO, Stolzle A, Lumenta CB. Preoperative embolization of intracranial meningiomas with Embosphere((R)) microspheres. Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery. 2004;47(5):299–305. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chun HJ, et al. An experimental study for syndiotactic polyvinyl alcohol spheres as an embolic agent: Can it maintain spherical shape in vivo? Bio-Medical Materials and Engineering. 2014;24(4):1743–1750. doi: 10.3233/BME-140986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SG, et al. Preparation of novel syndiotactic poly(vinyl alcohol) microspheres through the low-temperature suspension copolymerization of vinyl pivalate and vinyl acetate and heterogeneous saponification. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2005;95(6):1539–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stampfl U, et al. Experimental Liver Embolization with Four Different Spherical Embolic Materials: Impact on Inflammatory Tissue and Foreign Body Reaction. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2009;32(2):303–312. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malagari K, et al. Transcatheter chemoembolization in the treatment of HCC in patients not eligible for curative treatments: midterm results of doxorubicin-loaded DC bead. Abdominal Imaging. 2008;33(5):512–519. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grosso M, et al. Transarterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Drug-Eluting Microspheres: Preliminary Results from an Italian Multicentre Study. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2008;31(6):1141–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan O, et al. Comparative Study of Chemoembolization Loadable Beads: In vitro Drug Release and Physical Properties of DC Bead and Hepasphere Loaded with Doxorubicin and Irinotecan. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2010;21(7):1084–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forman D, Ferlay J. World Cancer Report in The global and regional burden of cancer. In: Stewart BW, Wild CP, editors. IARC: 150 Cours. Albert Thomas; 69372 Lyon CEDEX 08, France: 2014. pp. 16–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forner A, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology. 2006;60(2):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varela M, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: is there an optimal strategy? Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2003;29(2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(02)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruix J, et al. Focus on hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(3):215–219. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin SM. Recent advances of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;22:A74–A74. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Padhya KT, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Recent advances in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2013;29(3):285–292. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835ff1cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singal AG, Marrero JA. Recent advances in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2010;26(3):189–195. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283383ca5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Himoto T, et al. Recent Advances in Radiofrequency Ablation for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatitis Monthly. 2012;12(10) doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minami Y, Kudo M. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma:Current status. World Journal of Radiology. 2010;2(11):8. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i11.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruix J, et al. New aspects of diagnosis and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25(27):3848–3856. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Llovet JM, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sikander A, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization in a patient with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis - A case report and review of the literature. American Journal of Clinical Oncology-Cancer Clinical Trials. 2005;28(6):638–639. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000158488.36371.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Toole D, Ruszniewski P. Chemoembolization and other ablative therapies for liver metastases of gastrointestinal endocrine tumours. Best Practice & Research in Clinical Gastroenterology. 2005;19(4):585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allison DJ, Modlin IM, Jenkins WJ. TREATMENT OF CARCINOID LIVER METASTASES BY HEPATIC-ARTERY EMBOLIZATION. Lancet. 1977;2(052):1323–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuang VP, Wallace S, Gianturco C. A NEW IMPROVED COIL FOR TAPERED-TIP CATHETER FOR ARTERIAL-OCCLUSION. Radiology. 1980;135(2):507–509. doi: 10.1148/radiology.135.2.7367647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gianturco C, Anderson JH, Wallace S. MECHANICAL DEVICES FOR ARTERIAL-OCCLUSION. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1975;124(3):428–435. doi: 10.2214/ajr.124.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace S, et al. THERAPEUTIC VASCULAR OCCLUSION UTILIZING STEEL COIL TECHNIQUE - CLINICAL APPLICATIONS. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1976;127(3):381–387. doi: 10.2214/ajr.127.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson JH, et al. MINI GIANTURCO STAINLESS-STEEL COILS FOR TRANSCATHETER VASCULAR OCCLUSION. Radiology. 1979;132(2):301–303. doi: 10.1148/132.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allison DJ, Jordan H, Hennessy O. THERAPEUTIC EMBOLIZATION OF THE HEPATIC-ARTERY - A REVIEW OF 75 PROCEDURES. Lancet. 1985;1(8429):595–599. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Meta-analysis of arterial embolization. Radiology. 2004;230(1):300–301. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301030753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Llovet JM, Bruix J, G. Barcelona Clin Liver Canc Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37(2):429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lo CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35(5):1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dreher MR, et al. Radiopaque Drug-Eluting Beads for Transcatheter Embolotherapy: Experimental Study of Drug Penetration and Coverage in Swine. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2012;23(2):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis AL, et al. Doxorubicin eluting beads-1: Effects of drug loading on bead characteristics and drug distribution. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 2007;18(9):1691–1699. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lewis AL, et al. DC bead: In vitro characterization of a drug-delivery device for transarterial chemoembolization. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2006;17(2):335–342. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000195323.46152.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewis AL, Holden RR. DC Bead embolic drug-eluting bead: clinical application in the locoregional treatment of tumours. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2011;8(2):153–169. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.545388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewis AL, Dreher MR. Locoregional drug delivery using image-guided intra-arterial drug eluting bead therapy. Journal of Controlled Release. 2012;161(2):338–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lewandowski RJ, et al. Transcatheter Intraarterial Therapies: Rationale and Overview. Radiology. 2011;259(3):641–657. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liapi E, Geschwind JFH. Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization for Liver Cancer: Is It Time to Distinguish Conventional from Drug-Eluting Chemoembolization? Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2011;34(1):37–49. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-0012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamada R, et al. HEPATIC-ARTERY EMBOLIZATION IN 120 PATIENTS WITH UNRESECTABLE HEPATOMA. Radiology. 1983;148(2):397–401. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.2.6306721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Konno T, et al. EFFECT OF ARTERIAL ADMINISTRATION OF HIGH-MOLECULAR-WEIGHT ANTI-CANCER AGENT SMANCS WITH LIPID LYMPHOGRAPHIC AGENT ON HEPATOMA - A PRELIMINARY-REPORT. European Journal of Cancer & Clinical Oncology. 1983;19(8):1053–&. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stampfl U, et al. Midterm Results of Uterine Artery Embolization Using Narrow-Size Calibrated Embozene Microspheres. Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology. 2011;34(2):295–305. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sadick M, et al. Application of DC Beads in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Clinical and Radiological Results of a Drug Delivery Device for Transcatheter Superselective Arterial Embolization. Onkologie. 2010;33(1–2):31–37. doi: 10.1159/000264620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aliberti C, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) of liver metastases (LM) from colorectal carcinoma (CRC) adopting drug eluting beads preloaded with irinotecan (DEBIRI): Results of a phase II study on 82 patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(15) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fiorentini G, et al. Intra-arterial Hepatic Chemoembolization (TACE) of Liver Metastases from Ocular Melanoma with Slow-release Irinotecan-eluting Beads. Early Results of a Phase II Clinical Study. In Vivo. 2009;23(1):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eichler K, et al. First human study in treatment of unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer with irinotecan-loaded beads (DEBIRI) International Journal of Oncology. 2012;41(4):1213–1220. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharma KV, et al. Development of “Imageable” Beads for Transcatheter Embolotherapy. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2010;21(6):865–876. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fiorentini G, et al. TRANS-ARTERIAL CHEMOEMBOLIZATION OF METASTATIC COLORECTAL CARCINOMA (MCRC) TO THE LIVER ADOPTING POLYVINYL ALCOHOL MICROSPHERES (PAM) LOADED WITH IRINOTECAN COMPARED WITH FOLFIRI (CT): EVALUATION AT TWO YEARS OF A PHASE III CLINICAL TRIAL. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21:191–191. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonzalez MV, et al. Doxorubicin eluting beads - 2: methods for evaluating drug elution and in-vitro : in-vivo correlation. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 2008;19(2):767–775. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang Y, et al. Evaluation of irinotecan drug-eluting beads: A new drug-device combination product for the chemoembolization of hepatic metastases. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;116(2):E55–E56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taylor RR, et al. Irinotecan drug eluting beads for use in chemoembolization: In vitro and in vivo evaluation of drug release properties. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;30(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaiser E, et al. COLOR TEST FOR DETECTION OF FREE TERMINAL AMINO GROUPS IN SOLID-PHASE SYNTHESIS OF PEPTIDES. Analytical Biochemistry. 1970;34(2):595–&. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mawad D, et al. Synthesis and characterization of radiopaque iodine-containing degradable PVA hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(1):263–268. doi: 10.1021/bm700754m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okamura M, et al. Synthesis and properties of radiopaque polymer hydrogels: polyion complexes of copolymers of acrylamide derivatives having triiodophenyl and carboxyl groups and p-styrene sulfonate and polyallylamine. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2000;554(1):35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jayakrishnan A, et al. PREPARATION AND EVALUATION OF RADIOPAQUE HYDROGEL MICROSPHERES BASED ON PHEMA IOTHALAMIC ACID AND PHEMA IOPANOIC ACID AS PARTICULATE EMBOLI. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1990;24(8):993–1004. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820240803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bendszus M, et al. Efficacy of trisacryl gelatin microspheres versus polyvinyl alcohol particles in the preoperative embolization of meningiomas. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2000;21(2):255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bendszus M, et al. MR imaging- and MR spectroscopy-revealed changes in meningiomas for which embolization was performed without subsequent surgery. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2000;21(4):666–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gaba RC, et al. Ethiodized Oil Uptake Does Not Predict Doxorubicin Drug Delivery after Chemoembolization in VX2 Liver Tumors. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2012;23(2):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Okamura M, et al. Synthesis and properties of radiopaque polymer hydrogels II: copolymers of 2,4,6-triiodophenyl- or N-(3-carboxy-2,4,6-triiodophenyl)-acrylamide and p-styrene sulfonate. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2002;602:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thanoo BC, Jayakrishnan A. BARIUM SULFATE-LOADED P(HEMA) MICROSPHERES AS ARTIFICIAL EMBOLI - PREPARATION AND PROPERTIES. Biomaterials. 1990;11(7):477–481. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(90)90061-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jayakrishnan A, Knepp WA, Goldberg EP. CASEIN MICROSPHERES - PREPARATION AND EVALUATION AS A CARRIER FOR CONTROLLED DRUG-DELIVERY. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1994;106(3):221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thanoo BC, Sunny MC, Jayakrishnan A. TANTALUM-LOADED POLYURETHANE MICROSPHERES FOR PARTICULATE EMBOLIZATION - PREPARATION AND PROPERTIES. Biomaterials. 1991;12(5):525–528. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Horak D, et al. HYDROGELS IN ENDOVASCULAR EMBOLIZATION .3. RADIOPAQUE SPHERICAL-PARTICLES, THEIR PREPARATION AND PROPERTIES. Biomaterials. 1987;8(2):142–145. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(87)90104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thanoo BC, Jayakrishnan A. RADIOPAQUE HYDROGEL MICROSPHERES. Journal of Microencapsulation. 1989;6(2):233–244. doi: 10.3109/02652048909098026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hagit A, et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Dual Modality (CT/MRI) Core-Shell Microparticles for Embolization Purposes. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(6):1600–1607. doi: 10.1021/bm100251s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]