Abstract

Background

Active surveillance (AS) attempts to avoid overtreatment of clinically insignificant prostate cancer (PCa), however patient selection remains controversial. Multiparametric prostate MRI (MP-MRI) may help better select AS candidates.

Methods

We reviewed a cohort of men who underwent MP-MRI with MRI/US fusion-guided prostate biopsy and selected potential AS patients at entry using the Johns Hopkins criteria. MP-MRI findings were assessed including number of lesions, dominant lesion diameter/volume, total lesion volume, prostate volume, and “lesion density” (calculated as total lesion volume/prostate volume). Lesions were assigned a suspicion score for cancer by MRI. AS criteria was reapplied based on the confirmatory biopsy and accuracy of MP-MRI in predicting AS candidacy was assessed. Logistic regression modeling and chi-square statistics were used to assess associations between MP-MRI interpretation and biopsy results.

Results

Eighty-five patients qualified for AS with a mean age of 60.2 years and mean PSA of 4.8 ng/ml. Of these, 25 patients (29%) were reclassified as not meeting AS criteria based on confirmatory biopsy. Number of lesions, lesion density, and highest MRI lesion suspicion were significantly associated with confirmatory biopsy AS reclassification. These MRI-based factors were combined to create a nomogram that generates a probability for confirmed AS candidacy.

Conclusion

As clinicians counsel patients with PCa, MP-MRI may contribute to the decision-making process when considering AS. Three MRI-based factors (number of lesions, lesion suspicion, and lesion density) were associated with confirmatory biopsy outcome and reclassification. A nomogram using these factors has promising predictive accuracy for which future validation is necessary.

Keywords: prostate neoplasms, active surveillance, magnetic resonance imaging, early detection of cancer

Introduction

At least 50–60% of individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer (PCa) ultimately die of other causes.1 In attempts to mitigate overtreatment of indolent PCa, active surveillance (AS) was introduced to identify those individuals with clinically insignificant disease and defer treatment until objective evidence of disease progression. This approach has been reported from several centers and has resulted in acceptable intermediate-term outcomes.2 Both the American Urologic Association clinical guidelines and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network advocate AS as a management option for low-risk PCa.3, 4

The challenge remains in differentiating those men who harbor indolent disease from those with clinically significant cancer that may progress if managed without definitive treatment.5 Common selection criteria for AS include a combination of clinical and pathologic factors, the latter of which are based on prostate biopsy.2 Unfortunately, the current standard-of-care template prostate biopsy results in pathologic undergrading in roughly one-third of cases when compared to the prostatectomy pathology.6, 7 Furthermore, some patients may have low grade PCa diagnosed with standard sextant biopsy, but could be harboring more aggressive PCa in areas more prone to be undersampled by standard biopsy (i.e. anterior prostate or transition zone). Due to the concern that biopsy inaccurately reflects true pathology, many urologists fear they will miss the window of opportunity to treat a curable cancer and therefore, are hesitant to proceed with enrolling patients in an AS protocol.8

To reduce the understaging of prostate biopsy, it has been suggested that prostate MRI be included in the selection criteria for AS.9–11 Our group and others have previously shown that multiparametric prostate MRI (MP-MRI) correlates with pathologic grade at surgery and can differentiate patients with low and high-risk PCa.12–15 Adding imaging factors to the typical management algorithm and criteria for AS may be justified with further validation. In this study, we evaluate the utility of MP-MRI in the selection and stratification of patients for AS.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

A retrospective review was performed of an Institutional Review Board-approved study with appropriate informed consent at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Study enrollment was initiated in August 2007 and continued through August 2012. Traditional template pathology was reviewed by a single pathologist and patients were included in this study if they met the Johns Hopkins AS criteria (PSA density ≤ 0.15, ≤ 2 positive cores, ≤ 50% tumor in any core, Gleason score ≤ 6, and stage T1c).16 All patients underwent baseline pre-biopsy MP-MRI. If targetable lesions were identified on MP-MRI, the patients subsequently underwent confirmatory 12-core TRUS-guided systematic extended prostate biopsy and targeted MRI/US fusion-guided biopsies with electromagnetic tracking, as previously described.17, 18 Candidacy for continued active surveillance was based on repeat biopsy results using the Johns Hopkins criteria. The targeted biopsy results were also incorporated into the assessment of continued candidacy with the criteria of ≤ 50% tumor in any core, Gleason score ≤ 6.

MP-MRI Data Acquisition and Analysis

MP-MRI was performed using the combination of an endorectal coil (BPX-30, Medrad, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) tuned to 127.8 MHz and a cardiac coil (16-channel) (SENSE, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH) on a 3T magnet (Achieva, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH). The endorectal coil was inserted using a semi-anesthetic gel (Lidocaine 2%, AstraZeneca, USA) while the patient was in the left lateral decubitus position. The balloon surrounding the coil was distended with perfluorocarbon (3 mol/L-Fluorinert, 3M, St. Paul, MN, USA) to a volume of approximately 50 mL to reduce susceptibility artifacts induced by air in the coil’s balloon. MRI sequence parameters were detailed in a prior study, and included triplanar T2 weighted (T2W) turbo-spin-echo (TSE), diffusion weighted (DW) MRI, 3 dimensional MR Spectroscopic Imaging, axial pre-contrast T1 weighted (T1W) MRI, and axial 3D fast field echo dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI.19

For multi-parametric MRI analysis on T2W MR and ADC maps of DW MRI, the criterion for a “visible” lesion was a well circumscribed, round-ellipsoid low-signal-intensity region within the prostate gland.19 The 3D-MR spectroscopy analysis evaluated choline/citrate (Cho/Cit) ratios. Voxels were considered abnormal when the (Cho/Cit) ratio was 3 or more standard deviations (SD) above the mean healthy Cho/Cit ratio value (≥0.373), which was defined as 0.13+/−0.081 based on prior results.19 DCE MR images were evaluated by direct visual interpretation of raw dynamic enhanced T1W images and the diagnostic criteria for prostate cancer included a focus of asymmetric, early and intense enhancement with rapid wash out compared to the background.19 The MP-MRI score assigned to each lesion is based on the number of positive sequences (e.g. positive T2W, Diffusion weighted, MR spectroscopy and DCE-MRI is indicative of a high score). In this non-weighted scoring system, lesion scores are categorized as low, moderate and high (Table 1).11 When compared to the prostatectomy pathology, the degree of suspicion has been shown to correlate with the D’amico risk stratification system, particularly in patients with low-risk disease.11, 14 The largest diameter of each lesion was calculated manually on a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) workstation (Carestream, Inc, USA). Again, each visible lesion was manually segmented on a research software platform (iCAD, Nashua, NH, USA) blinded to the clinical and histopathologic data. The tumor volume was determined with the same software after manual segmentation on MRI. For segmenting tumors on MRI, T2W MRI, ADC maps of DW MRI and DCE MRI sequences were used in conjunction although final ROIs were drawn on T2W MRI for targeting during fusion biopsy. Total prostate volumes were manually obtained for each patient using a semi-automated software, which was previously validated in a cohort of 500 patients.20

Table 1.

The National Cancer Institute MP-MRI evaluation score chart

| Findings of MRI Sequence | MP-MRI Suspicion Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2W MRI | ADC Map of DW- MRI | MR Spectroscopy | DCE MRI | |

| − | − | − | − | Negative |

| + | − | − | − | Low |

| + | + | − | − | Low |

| − | + | − | − | Low |

| − | − | + | − | Low |

| − | − | − | + | Low |

| + | − | + | − | Moderate |

| + | − | − | + | Moderate |

| − | + | + | − | Moderate |

| − | + | − | + | Moderate |

| + | + | + | − | Moderate |

| + | + | − | + | Moderate |

| − | − | + | + | Moderate |

| + | + | + | + | High |

Statistical Analysis

We sought to identify predictors of confirmed AS candidacy on repeat biopsy based on MP-MRI generated factors, including: total prostate volume; largest lesion diameter; largest lesion volume; total lesion volume; total lesion density (total lesion volume divided by total prostate volume); number of lesions; mean lesion suspicion; and highest lesion suspicion.

The Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine differences between normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively. The Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Patients were stratified according to AS candidacy based on the confirmatory biopsy results. Logistic regressions models were fitted for the prediction of confirmed AS candidacy. Multivariable logistic regression models were fitted also incorporating total biopsy number to control for this as a possible confounding variable.

Parameters significantly associated with continued AS candidacy were then combined to generate a predictive model using logistic regression analysis. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated and area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess for discriminative ability of the derived equation. A nomogram was generated utilizing the R software package (http://www.r-project.org/, rms package: http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/rms). The rms package was also used for logistic regression analyses. The JMP Pro 10.0 (SAS Institute Inc, 2012) package was utilized for all remaining statistical analysis.

To further evaluate the model’s performance, the nomogram-generated probability was calculated for every patient in the cohort. Cutpoints were then assessed for the nomogram-generated probability of disqualification from AS candidacy based on repeat biopsy. Negative predicted values (NPV) and positive predicted values (PPV) were calculated by comparing the nomogram-generated recommendation against the “standard-of-care” recommendation, based on the confirmatory biopsy results. Leave-one-out cross-validation analyses of the logistic regression model development were performed to evaluate potential data over-fitting.

Results

Table 2 shows the demographics of the AS cohort in this study. The cohort included 85 patients with a mean age of 60.2 years (range 40 to 79). Mean PSA was 4.8 ng/ml, which is reflective of the low risk nature of this study population. Table 3 demonstrates the differences between patients that remained AS candidates compared to those who no longer qualified based upon the confirmatory biopsy. A total of 25 patients no longer qualified for AS on confirmatory biopsy, of which 15 were due to Gleason score upgrading and the other 10 due to percent core length or number of positive 12-core biopsies. Smaller total prostate volume, increased numbers of MRI-identified lesions, higher MRI lesion suspicion, and increased lesion density were all significantly associated with disqualification from AS. The mean number of cores obtained per patient was higher in those patients who were subsequently disqualified from AS, and this difference approached statistical significance (although the absolute difference was only 1.2 biopsy cores). A separate analysis (not shown) was performed to assess for association of MRI suspicion with AS candidacy controlling for the total number of biopsies. MRI suspicion continued to demonstrate a statistically significant association with AS candidacy even when accounting and controlling for the number of biopsies performed. We also investigated factors associated with lesion density and found a significant association with MRI suspicion (mean 1.5% for low suspicion, 1.9% for moderate suspicion, and 4.1% for high suspicion, p < 0.001), but not with prostate volume.

Table 2.

Demographics

| Characteristic | Mean ± standard deviation (range) |

|---|---|

| Number of men | 85 |

| Age (years) | 60.2 ± 7.4 (40–79) |

| PSA (ng/ml) | 4.8 ± 2.2 (0.2 – 10.9) |

| Prostate volume (cm3) | 51.5 ± 18.9 (24 – 161) |

| PSA density (ng/ml cm3) | 0.09 ± 0.03 (0.01 – 0.15) |

| Race | 84% White, 14% African American, 2% other |

Table 3.

MRI Findings (reported as mean ± standard deviation)

| AS Candidate | Not AS Candidate | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of men | 60 | 25 | |

| Age | 60.5 ± 7.3 | 59.6 ± 7.6 | 0.6 |

| Prostate volume (cm3) | 54.3 ± 19.8 | 45.0 ± 15.0 | 0.03 |

| # lesions on MRI | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 0.03 |

| Largest lesion diameter (cm) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Largest lesion volume (cm3) | 0.65 ± 0.57 | 0.87 ± 1.1 | 0.2 |

| Sum all lesion volumes (cm3) | 0.90 ± 0.75 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 0.1 |

| Lesion density (% of total volume) | 1.7% ± 1.5% | 2.7% ± 2.4% | 0.03 |

| # of total biopsy cores | 17.6 ± 2.7 | 18.8 ± 2.7 | 0.054 |

| MRI Suspicion: | 0.021 | ||

| Low | 24 (40%) | 3 (12%) | |

| Medium | 32 (53%) | 17 (68%) | |

| High | 4 (7%) | 5 (20%) |

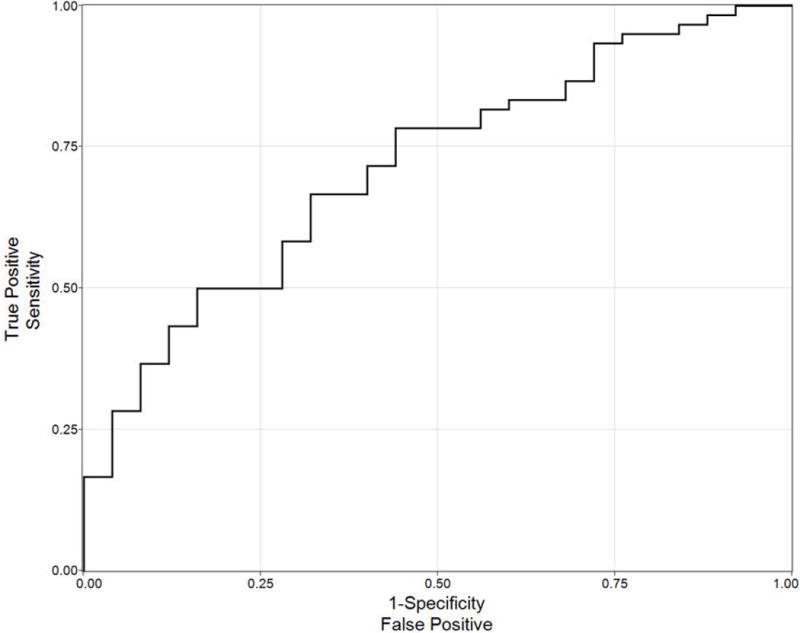

In order to generate a predictive model, we included three parameters from the univariate analysis in Table 3 that demonstrated significant associations with AS candidacy. These factors (number of lesions on MRI, lesion density, and highest MRI suspicion) were chosen not only because of their statistical association with confirmed AS candidacy, but also because these parameters are plausible indicators of tumor burden that could feasibly be followed serially over time by MRI. A logistic regression model was used to derive an equation relating AS candidacy to number of lesions on MRI, lesion density, and highest lesion suspicion seen on MRI. The fit demonstrated a significant association with AS candidacy (p = 0.02) and the ROC curve for the resultant equation can be seen in Figure 1 with an associated AUC = 0.71.

Figure 1.

ROC curve of logistic model incorporating number of lesions, suspicion, and lesion density

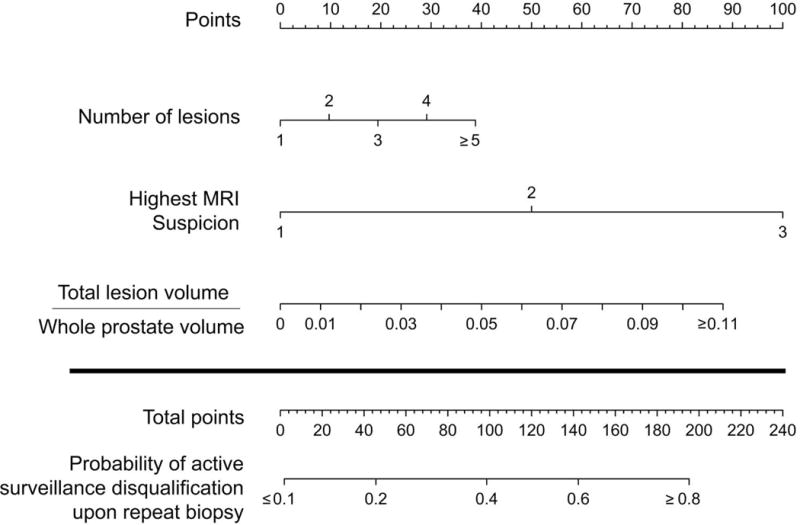

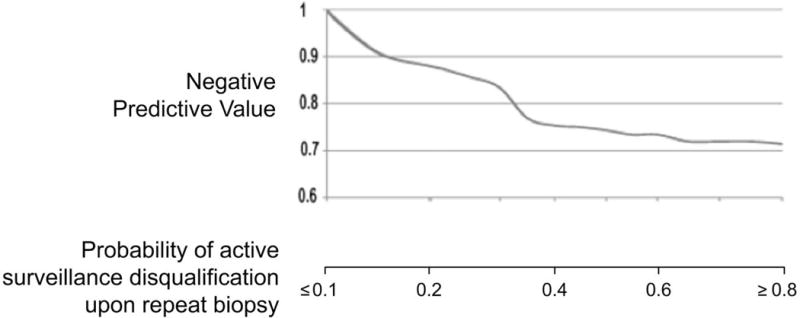

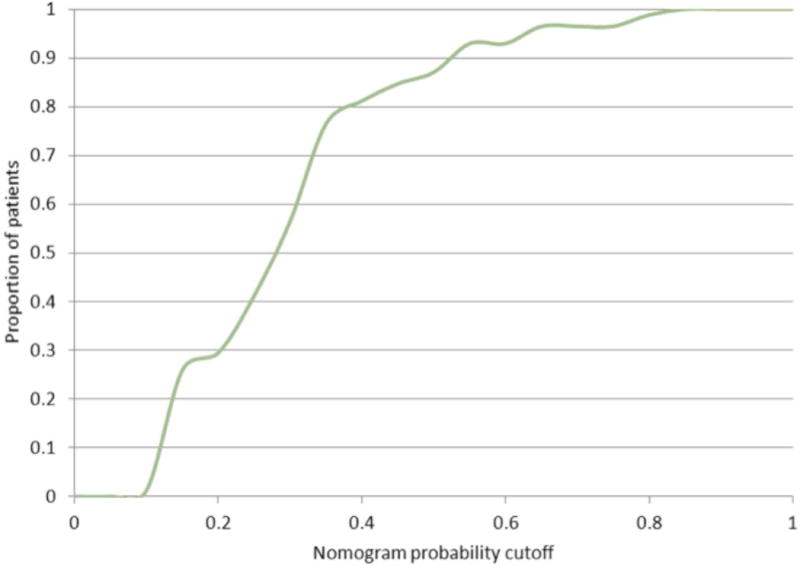

A nomogram was then generated using this logistic regression analysis (Figure 2a). The performance of the nomogram on the original dataset was determined by examining nomogram-generated AS candidacy versus confirmatory biopsy-derived AS candidacy. The NPV and PPV at all possible cutoffs were calculated. Of note, the nomogram did not perform well in regards to PPV (range 30–70%), but did perform well in regards to NPV (Figure 2b). In this way, the nomogram performs best as a diagnostic test in determination of patients that should remain on AS. Figure 3 shows the percent of patients that would not require a confirmatory biopsy for each corresponding nomogram percent cutoff. “Leave-one-out” cross-validation analyses were performed of the logistic regression prediction model on which the nomogram was based, and of a full model developed without selecting the variables that were univariately correlated with biopsy result. These analyses gave AUC values for the cross-validated ROC curves very similar to that reported above, providing little indication of data over-fitting.

Figure 2a.

Nomogram using MP-MRI findings alone to predict the probability of confirming active surveillance candidacy in patients who would otherwise qualify for active surveillance based on initial prostate biopsy.

Figure 2b.

Nomogram-generated probability with negative predictive values for each potential cutoff probability.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients who would hypothetically be spared a confirmatory biopsy for a given nomogram-generated cutoff probability.

Discussion

The foundation of AS of PCa rests on the ability to identify cancer that is of sufficiently low grade, stage, and/or volume to predict a low likelihood of future progression. While the principle is fundamentally intuitive, understaging significant disease and delaying potentially beneficial treatment remains a challenge. Selection criteria for AS is based on risk stratification to identify those men who are unlikely to be affected by their cancer based on their individual clinical features (age, associated comorbidities, etc.) and “tumor metrics” (stage, grade, PSA).8 Unfortunately, the ability of extended template prostate biopsies to reflect the true pathology obtained from the prostatectomy specimen is less than perfect. A meta-analysis of 15 studies including 14,839 patients who underwent prostatectomy revealed that Gleason grade on initial biopsy is upgraded in 30% of surgeries.6 Perhaps MRI/US fusion-guided prostate biopsy may be better on a core-by-core analysis, but this technology also remains imperfect due to sampling error, registration error, and the nature of representative sampling.

Even amongst patients who would have been considered ideal candidates for AS by standard criteria, many patients harbor more aggressive disease. This observation is demonstrated by several series of patients meeting AS criteria who underwent radical prostatectomy, revealing Gleason score upgrading in 23–56%.7 Moreover, inferences of tumor volume are currently based on surrogate factors from the prostate biopsy pathology (i.e. number of cores involved with cancer and percentage of cancer within any given core involved with cancer), which have been shown to correlate with final pathologic cancer volume on the prostatectomy specimen.21, 22 Because these predictors were identified on varying biopsy schemas, the applicability of these factors in the era of extended and template-mapping biopsies is unclear and can further complicate the selection of AS candidates. To help overcome these shortcomings, most centers now recommend confirmatory prostate biopsy, especially if the initial biopsy was not performed with an extended template.2, 23 While a confirmatory biopsy may help to reduce understaging of the initial biopsy, it too is subject to the same shortcomings as the initial biopsy. One study of 124 men on AS compared confirmatory biopsy to template prostate mapping and concluded that confirmatory prostate biopsy can miss up to 80% of clinically significant tumors with associated NPVs between 23% and 60%.24

MP-MRI has emerged as a potentially useful modality in the diagnosis and staging of PCa. As the technology has improved, MP-MRI can now identify abnormal lesions throughout the prostate, including anterior lesions that are often missed by traditional TRUS biopsy.25 To help reduce inter-observer variability, our group has reported a high, moderate, and low suspicion grading system based upon objective findings from the various MP-MRI sequences, which accurately correlate with D’Amico risk categories.11, 14 Specifically, low suspicion lesions that have undergone targeted fusion biopsy tend to be either low-grade prostate cancer or bear non-cancerous pathology.26 The volume of the prostate and individual lesions can also be easily calculated with MP-MRI and accurately reflect the actual volumes of cancerous lesions observed on whole mount prostate histopathology.27 These measurements were used in the current study to calculate composite lesion density, which we propose as a surrogate for tumor burden.

The use of MP-MRI has recently been proposed as a modality to help in the selection and monitoring of AS patients. Vargas and colleagues reported on 388 patients with low-risk PCa who subsequently underwent endorectal MRI before confirmatory biopsy (standard 12-core biopsy and 2 additional cores obtained from the transition zone); each MRI was given a score using a 5-point scale that corresponded to the degree of suspicion of tumor presence.28 Low scores had a high NPV for pathologic upgrading on the confirmatory biopsy, while the highest score predicted clinically significant disease that would disqualify the patient from AS. Shukla-Dave and colleagues developed a nomogram incorporating clinical factors (clinical stage, pre-treatment PSA, and prostate volume) and suspicion score based on limited T2W MRI with spectroscopy only to predict the probability of clinically insignificant disease.29 This nomogram was of limited clinical utility with a NPV of the MRI ranging between 56–75%, depending on the radiologist and whether spectroscopy was included in the radiologic interpretation. Moreover, only up to 7% of the cohort had findings suggestive of “definitely insignificant PCa” or “probably insignificant PCa” on MRI, which may not be reflective of the true prevalence of clinically insignificant PCa.

Among a cohort of patients who met the Johns Hopkins AS criteria based on initial clinicopathologic biopsy data and subsequently underwent MP-MRI, we found that the number of MRI-identified lesions, highest MRI suspicion, and lesion density were significant predictors of AS candidacy based on confirmatory biopsy. The JHU criteria was chosen due to its rigor in inclusion of patients with low grade, low volume lesions, which we felt would be helpful for development of a predictive model that focuses on the identification of such patients. These MRI-based factors were combined to create a nomogram that predicts the probability of confirming AS candidacy with high NPV. Our intention was to create a predictive model based on variables derived from the MRI alone in an attempt to avoid the subjectivity associated with clinical staging and the variation in serum PSA values that are often seen in clinical practice.

We further modeled implications of using cutoff probabilities, below which the likelihood of disease progression (as determined by confirmatory biopsy) was low enough to obviate the need for a confirmatory biopsy. Based on our analysis, the nomogram performed very well with a NPV between 80–90% for confirming AS candidacy depending on the cutpoint used. Utilization of the nomogram has the potential to reduce the number of confirmatory biopsies performed on AS patients who likely have low-risk disease based on MP-MRI, which would eliminate the morbidity of these serial biopsies and the associated medical costs.

In practice, the clinician would vary his use of the MRI nomogram based on the mutual comfort level of the clinician and patient; this balance would certainly depend on other clinical factors (i.e. age, associated co-morbidities, estimated life expectancy, etc.). For a higher threshold probability on the nomogram below which AS is pursued without pathologic confirmation, more patients are spared confirmatory biopsies, but the corresponding NPV of the MP-MRI for confirming AS candidacy on repeat biopsy is reduced. For example, if a cutoff probability of 0.15 is used, this nomogram provides a corresponding NPV of approximately 91% (Figure 2b). Using Figure 3, we see that 26% of patients in this AS cohort would be spared a confirmatory biopsy using a cutoff probability of 0.15. Alternatively, if a cutoff of 0.3 is used, the NPV decreases to 83%, but 56% of patients would be spared a confirmatory biopsy. These estimates, however, are subject to sampling variability and patient selection bias; larger confirmation studies are needed to increase the precision of the nomogram and the estimated relationship between nomogram cutpoint and NPV.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Although the subjects were enrolled prospectively into a trial investigating the use of MP-MRI and MR/US fusion-guided prostate biopsy, the subset analysis of AS patients was retrospective in nature and subject to the inherent biases of such studies. Current MR scoring systems are not standardized and may make our model difficult to apply to a center that uses a different radiologic lesion suspicion score. A recent report from the European Society of Urogenital Radiology proposes a scoring system (PI-RADS classification) to allow for consistent reporting of MP-MRI results worldwide.30 At the time of this report, we are beginning to use the PI-RADS classification and will be prospectively comparing the predictive accuracy of this system to the NCI suspicion scoring system. Furthermore, the confirmatory biopsy that was performed on the study population used a MR/US fusion-guided platform, which has registration and tracking errors. Fusion biopsy is a cluster of emerging technologies that is becoming more widely available, but still lacks consensus on a standardized technique. Our methodology introduces bias since subjects without targetable lesions on MP-MRI were not considered in the validation. Moreover, the average number of cores at confirmatory biopsy was 18 (standard plus fusion) and thus, our results may not mirror the outcomes of clinicians performing standard 12-core confirmatory biopsies alone. Although the model performed well with internal validation using bootstrap analysis, external validation of this nomogram is also necessary to determine its general applicability to potential AS patients. Until such validation is published, this tool should be considered strictly a research tool to aid multi-institutional assessment of the use of MP-MRI in men with PCa on AS and not currently a clinical decision making tool. Finally, while we intentionally attempted to create a predictive model based on imaging-only variables, we acknowledge that incorporation of other classically relevant data (PSA, clinical stage, age, comorbidity indices, etc.) may help to build a stronger nomogram with better predictive capability. We hope to confirm our model with external datasets with subsequent plans to create a more comprehensive model with such additional variables that could further predict AS candidacy.

Conclusions

As urologists counsel patients with newly diagnosed PCa, MP-MRI may contribute to the decision-making process when considering AS. Number of MRI-identified lesions, highest MRI suspicion, and lesion density were associated with confirmatory biopsy outcome. A nomogram using these three MRI-based factors was formulated to calculate a probability for confirmed AS candidacy in patients with lesions identified by MP-MRI. If validated, such a model may help obviate the need for confirmatory prostate biopsy in certain candidates for AS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. NIH and Philips Healthcare have a cooperative research and development agreement. NIH and Philips share intellectual property in the field. This research was also made possible through the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from Pfizer Inc, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, as well as other private donors. For a complete list, please visit the Foundation website at http://www.fnih.org/work/programs-development/medical-research-scholars-program.

We wish to thank Kelly Holliday and Georgia Shaw of the Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research for assisting with the manuscript review and submission processes.

Footnotes

p-value reflects association with MRI-suspicion score globally with AS candidacy

References

- 1.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Outcomes of localized prostate cancer following conservative management. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1202–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27):3669–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCC Network. Prostate Cancer (Version 1.2013) Available from URL: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf[accessed December 18, 2012.

- 4.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2106–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooperberg MR, Broering JM, Kantoff PW, Carroll PR. Contemporary trends in low risk prostate cancer: risk assessment and treatment. J Urol. 2007;178(3 Pt 2):S14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MS, Hanley RS, Kurteva T, et al. Comparing the Gleason prostate biopsy and Gleason prostatectomy grading system: the Lahey Clinic Medical Center experience and an international meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2008;54(2):371–81. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti SL, Dall’era M, Fradet V, Cowan JE, Simko J, Carroll PR. Pathological outcomes of candidates for active surveillance of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2009;181(4):1628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.107. discussion 33–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter HB. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: an underutilized opportunity for reducing harm. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(45):175–83. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ukimura O. Evolution of precise and multimodal MRI and TRUS in detection and management of early prostate cancer. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2010;7(4):541–54. doi: 10.1586/erd.10.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer EA, Kaushal A, Turkbey B, Couvillon A, Pinto PA, Parnes HL. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: past, present and future. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24(3):243–50. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283527f99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O, et al. Prostate Cancer: Can Multiparametric MR Imaging Help Identify Patients Who Are Candidates for Active Surveillance? Radiology. 2013 doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittencourt LK, Barentsz JO, de Miranda LC, Gasparetto EL. Prostate MRI: diffusion-weighted imaging at 1.5T correlates better with prostatectomy Gleason Grades than TRUS-guided biopsies in peripheral zone tumours. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(2):468–75. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turkbey B, Shah VP, Pang Y, et al. Is apparent diffusion coefficient associated with clinical risk scores for prostate cancers that are visible on 3-T MR images? Radiology. 2011;258(2):488–95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rastinehad AR, Baccala AA, Jr, Chung PH, et al. D’Amico risk stratification correlates with degree of suspicion of prostate cancer on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;185(3):815–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hambrock T, Somford DM, Huisman HJ, et al. Relationship between apparent diffusion coefficients at 3.0-T MR imaging and Gleason grade in peripheral zone prostate cancer. Radiology. 2011;259(2):453–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11091409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Landis P, et al. Active surveillance program for prostate cancer: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(16):2185–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto PA, Chung PH, Rastinehad AR, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy improves cancer detection following transrectal ultrasound biopsy and correlates with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. J Urol. 2011;186(4):1281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turkbey B, Xu S, Kruecker J, et al. Documenting the location of prostate biopsies with image fusion. BJU Int. 2011;107(1):53–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkbey B, Pinto PA, Mani H, et al. Prostate cancer: value of multiparametric MR imaging at 3 T for detection–histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2010;255(1):89–99. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turkbey B, Huang R, Vourganti S, et al. Age-related changes in prostate zonal volumes as measured by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): a cross-sectional study in over 500 patients. BJU Int. 2012;110(11):1642–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochiai A, Troncoso P, Chen ME, Lloreta J, Babaian RJ. The relationship between tumor volume and the number of positive cores in men undergoing multisite extended biopsy: implication for expectant management. J Urol. 2005;174(6):2164–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181211.49267.43. discussion 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noguchi M, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Yemoto CM. Relationship between systematic biopsies and histological features of 222 radical prostatectomy specimens: lack of prediction of tumor significance for men with nonpalpable prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;166(1):104–9. discussion 09–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamy A, Yee DS, Matsushita K, et al. Role of prostate specific antigen and immediate confirmatory biopsy in predicting progression during active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;185(2):477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barzell WE, Melamed MR, Cathcart P, Moore CM, Ahmed HU, Emberton M. Identifying candidates for active surveillance: an evaluation of the repeat biopsy strategy for men with favorable risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188(3):762–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vourganti S, Rastinehad A, Yerram NK, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound fusion biopsy detect prostate cancer in patients with prior negative transrectal ultrasound biopsies. J Urol. 2012;188(6):2152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yerram NK, Volkin D, Turkbey B, et al. Low suspicion lesions on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging predict for the absence of high-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O, et al. Correlation of magnetic resonance imaging tumor volume with histopathology. J Urol. 2012;188(4):1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargas HA, Akin O, Afaq A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for predicting prostate biopsy findings in patients considered for active surveillance of clinically low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188(5):1732–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shukla-Dave A, Hricak H, Akin O, et al. Preoperative nomograms incorporating magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy for prediction of insignificant prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109(9):1315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(4):746–57. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]