Abstract

Objectives:

While various short variants of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) have been developed, they have not been compared among each other to determine the most optimal variant for routine use. This study evaluated the comparative performance of the short variants in identifying mild cognitive impairment or dementia (MCI/dementia).

Design:

Baseline data of a cohort study.

Setting:

Alzheimer’s Disease Centers across the United States.

Participants:

Participants aged ≥50 years (n=4,606), with median age 70 (interquartile range 65–76)

Measures:

Participants completed MoCA and were evaluated for MCI/dementia. The various short variants of MoCA were compared in their performance in discriminating MCI/dementia, using areas-under-the-receiver-operating-characteristic-curve (AUC).

Results:

All seven short variants of MoCA had acceptable performance in discriminating MCI/dementia from normal cognition (AUC 87.7–91.0%). However, only two variants by Roalf (2016) and Wong (2015) demonstrated comparable performance (AUC 88.4–88.9%) to the original MoCA (AUC 89.3%). Among the participants with higher education, only the variant by Roalf (2016) had similar AUC to the original MoCA. At the optimal cut-off score of <25, the original MoCA demonstrated 84.4% sensitivity and 76.4% specificity. In contrast, the short variant by Roalf (2016) had 87.2% sensitivity and 72.1% specificity at its optimal cut-off score of <13.

Conclusions and Implications:

The various short variants may not share similar diagnostic performance, with many limited by ceiling effects among participants with higher education. Only the short variant by Roalf (2016) was comparable to the original MoCA in identifying MCI or dementia even across education subgroups. This variant is one-third the length of the original MoCA and can be completed in <5 minutes. It provides a viable alternative when the original MoCA cannot be feasible administered in clinical practice, and can be especially useful in non-specialty clinics with large volume of patients at high-risk of cognitive impairment (such as those in primary-care, geriatric, and stroke-prevention clinics).

INTRODUCTION

Detailed neuropsychological testing plays an essential role in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia.1 However, it can be time-consuming and may not be well-suited for routine use outside of specialized memory clinics. As such, it has often been replaced by brief cognitive tests in the diagnostic evaluation of MCI and dementia, with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)2 being among the most widely-used tests.3 MoCA has many desirable characteristics. Compared to the traditionally popular Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), MoCA is freely available (at www.mocatest.org), has been translated into multiple languages, includes more robust measures of visuospatial and executive function, and has better diagnostic performance than MMSE in detecting MCI.2,3 Nevertheless, its administration time is still less than ideal and can remain prohibitive in many non-specialty clinics with high patient load and limited resources – it requires up to 15 minutes to administer even in the healthy population and can be almost two times longer than the administration time of MMSE.4–8

Consequently, various abbreviated versions of MoCA4–7,9–11 have been developed in the literature to reduce its administration time, by excluding items which contributed minimally to the overall diagnostic performance. As shown in Table 1, at least seven different versions of abbreviated MoCA have been published to date. While most of them have been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of MCI and dementia, they have not been compared among each other. It is uncertain which of these versions is most optimal for routine use, that is, having the least number of items while remaining comparable to the original MoCA in its diagnostic performance. This study sought to provide more conclusive evidence – using a large sample – on the comparative performance of the various short variants of MoCA in the diagnosis of MCI and dementia.

Table 1.

Overview of the short variants of MoCA that were evaluated in this study

| MoCA variant (by author and year) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roalf (2016)5 | Wong (2015)6a | Horton (2015)7 | Bezdicek (2018)4 | Dong (2016)9b | Bocti (2013)10 | Mai (2013)11 | |

| 1. Visuospatial/Executive – Trails | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2. Visuospatial/Executive – Cube | ✓ | ||||||

| 3. Visuospatial/Executive – Clock drawing | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 4. Language – Naming (lion) | |||||||

| 5. Language – Naming (rhinoceros) | ✓ | ||||||

| 6. Language – Naming (camel) | |||||||

| 7. Memory – Registration (first trial) | ✓ | ||||||

| 8. Attention – Digit span forward | |||||||

| 9. Attention – Digit span backward | ✓ | ||||||

| 10. Attention – Tap at letter A | |||||||

| 11. Attention – Serial 7s | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 12. Language – Repetition (John) | |||||||

| 13. Language – Repetition (cat) | ✓ | ||||||

| 14. Language – Fluency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15. Abstraction – Train | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 16. Abstraction – Watch | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 17. Delayed recall | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 18. Orientation – Date | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 19. Orientation – Month | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 20. Orientation – Year | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 21. Orientation – Day | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 22. Orientation – Place | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 23. Orientation – City | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

the items in this variant are scored differently from the original MoCA – Registration (maximum 5 points, based on the first trial), Fluency (maximum 9 points, with 0.5 points for each correct answer), Orientation (maximum 6 points), and Delayed recall (maximum 10 points, with 2 points for each spontaneous recall, and 1 point for cued recall or recognition).

based on the 5-minutes protocol proposed by the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke–Canadian Stroke Network

METHOD

Study population

This study is based on the baseline data of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) cohort.12 It included individuals who: (1) were recruited from the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers across the United States from March 2015 (the date when MoCA was first introduced in the NACC database) to May 2018; (2) age ≥50 years; (3) completed MoCA at baseline; and (4) completed standardized assessments to evaluate for the presence of MCI or dementia. Research using the NACC database was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Measures

MoCA2 is a widely-used cognitive assessment tool. It assesses cognitive functions in the following seven domains: Visuospatial/Executive, Naming, Attention, Language, Abstraction, Delayed recall and Orientation. The test has a maximum score of 30 with higher scores corresponding to better cognition.

The diagnoses of normal cognition, MCI or dementia were made based on all available data, with majority of the diagnoses made via consensus conference (in 88.1% of the participants) and the remainder made by single clinicians. MCI was diagnosed using modified Petersen criteria;13 while dementia was diagnosed with McKhann (2011) criteria14 with further classification into the primary etiologies of Alzheimer’s dementia,14 vascular dementia,15 dementia with Lewy Bodies,16,17 frontotemporal lobar degeneration,18–21 or other etiologies.

Statistical analyses

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was computed to assess the performance of each MoCA variant in discriminating the baseline diagnoses of MCI and dementia from normal cognition. The analysis was conducted for the whole sample, as well as stratified for the education subgroups (≤12 years of education; and >12 years of education). AUC of the MoCA variants were compared to that of the original MoCA via a non-parametric approach,22 with Bonferroni adjustment of the p-values to account for multiple comparisons. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was also conducted to assess the performance of the variants in discriminating dementia from non-dementia. All analyses were conducted in Stata (version 14).

RESULTS

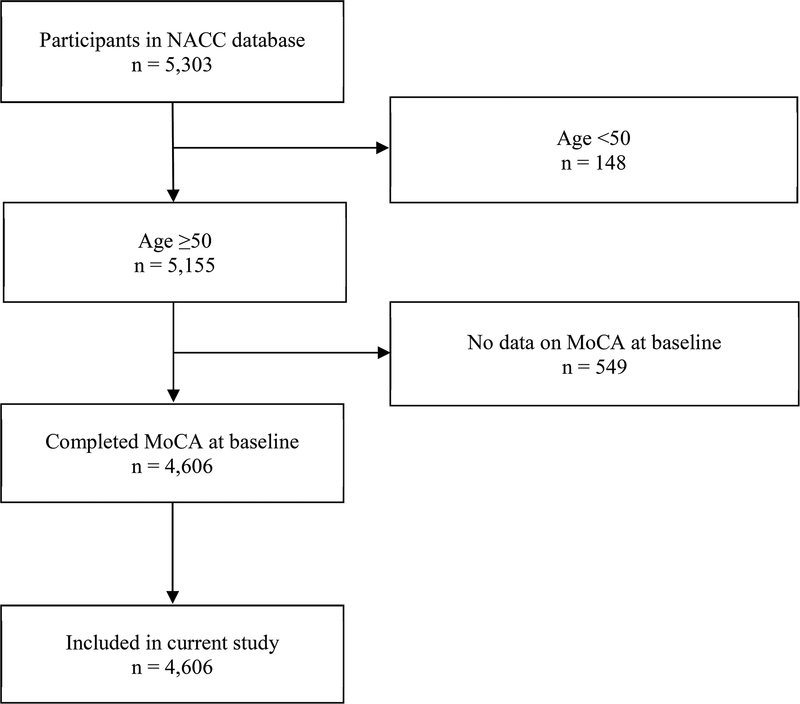

The total sample size was 4,606, comprising 48.7% normal cognition, 24.0% MCI and 27.3% dementia. Among the participants with dementia (n=1,259), 69.3% had the primary etiology of Alzheimer’s dementia, 0.7% had vascular dementia, 5.2% mixed Alzheimer’s/vascular dementia, 5.5% dementia with Lewy Bodies, 16.3% frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and 2.9% due to other or unknown etiology. The flow diagram related to participant selection is presented in Figure 1, while the participant characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. Participant enrolment and exclusion details.

NACC, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study participants at baseline (n=4,606)

| Variable | Overall sample (n=4,606) |

Normal cognition (n=2,240) |

MCI (n=1,107) |

Dementia (n=1,259) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 70 (65–76) | 69 (65–74) | 72 (67–78) | 71 (63–77) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 2,655 (57.6) | 1,456 (65.0) | 546 (49.3) | 653 (51.9) |

| Years of education, median (IQR) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (15–18) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (13–18) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 3,675 (79.8) | 1,681 (75.0) | 881 (79.6) | 1,113 (88.4) |

| African American | 624 (13.5) | 372 (16.6) | 156 (14.1) | 96 (7.6) |

| Others/Unknown | 307 (6.7) | 187 (8.4) | 70 (6.3) | 50 (4.0) |

| MoCA total score, median (IQR) | 24 (19–27) | 27 (25–28) | 23 (20–25) | 15 (11–20) |

IQR, interquartile range; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MoCA, Monteral Cognitive Assessment.

Table 3 shows the diagnostic performance of the MoCA variants in discriminating MCI and dementia from normal cognition (stratified by educational attainment). All the seven short variants of MoCA demonstrated acceptable AUC (ranging from 87.7% to 88.9%). However, only the variants by Roalf (2016)5 and Wong (2015)6 had AUC which were not significantly different from that of the original MoCA in identifying MCI and dementia. Most of the MoCA variants demonstrated comparable AUC (to the original MoCA) among participants with ≤12 years of education, but had poorer AUC among those with >12 years of education. Notably, only the variant by Roalf (2016)5 demonstrated similar AUC to that of the original MoCA in discriminating MCI and dementia among participants with >12 years of education.

Table 3.

Comparison of the performance of the MoCA variants to that of the original MoCA in identifying the baseline diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment or dementia (n=4,606).

| MoCA variant | Overall sample (n=4,606) | ≤12 years of education (n=724) | >12 years of education (n=3,882) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC, % (95% CI) | P-valuea | AUC, % (95% CI) | P-valuea | AUC, % (95% CI) | P-valuea | |||

| Original MoCA | 89.3 (88.4–90.2) | Ref | 87.8 (85.4–90.3) | Ref | 89.5 (88.5–90.5) | Ref | ||

| Roalf (2016) | 88.9 (88.0–89.9) | 0.500 | 87.3 (84.8–90.0) | 1.000 | 89.0 (87.9–90.0) | 0.161 | ||

| Wong (2015) | 88.4 (87.4–89.3) | 0.063 | 88.3 (85.9–90.7) | 1.000 | 88.1 (87.1–89.2) | 0.005 | ||

| Horton (2015) | 88.5 (87.5–89.4) | 0.044 | 87.4 (85.0–89.9) | 1.000 | 88.3 (87.3–89.4) | 0.007 | ||

| Bezdicek (2018) | 88.7 (87.8–89.6) | 0.003 | 86.4 (83.7–89.1) | 0.018 | 88.8 (87.8–89.8) | 0.007 | ||

| Dong (2016) | 88.3 (87.4–89.2) | 0.017 | 88.2 (85.8–90.5) | 1.000 | 88.0 (87.0–89.1) | <0.001 | ||

| Bocti (2013) | 87.7 (86.7–88.7) | <0.001 | 85.9 (86.7–88.7) | 0.107 | 87.8 (86.7–88.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Mai (2013) | 87.7 (86.7–88.6) | <0.001 | 86.2 (83.5–88.9) | 0.373 | 87.5 (86.5–88.6) | <0.001 | ||

MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference.

Bonferroni-adjusted p-values in the comparisons of AUC between the original MoCA and the respective short versions. Bold-faced p-values are ≤0.05 and indicate that the AUC of the respective short variant was significantly different from that of the original MoCA.

Table 4 presents a summary of the optimal cut-off scores for the MoCA variants in identifying MCI and dementia. The original MoCA demonstrated 84.4% sensitivity and 76.4% specificity at the optimal cut-off score of <25. Most of the MoCA variants had acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity (>70%) at their respective optimal cut-off scores. In particular, the short variant by Roalf (2016) had 87.2% sensitivity and 72.1% specificity at its optimal cut-off score of <13 (out of the maximum score of 16). Detailed results on the sensitivity and specificity statistics of each MoCA variant are further presented in Supplementary Material 1.

Table 4.

A summary of the optimal cut-off scores for the MoCA variants in identifying the baseline diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment or dementia (n=4,606).

| MoCA variant | Maximum score | Overall sample | ≤12 years of education | >12 years of education | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal cut-offa | Se, % |

Sp, % |

Optimal cut-offa | Se, % |

Sp, % |

Optimal cut-offa | Se, % |

Sp, % |

||||

| Original MoCA | 30 | <25 | 84.4 | 76.4 | <22 | 81.5 | 78.2 | <25 | 81.7 | 80.3 | ||

| Roalf (2016) | 16 | <13 | 87.2 | 72.1 | <11 | 81.9 | 78.6 | <13 | 85.2 | 75.6 | ||

| Wong (2015) | 30 | <25 | 84.4 | 73.0 | <23 | 85.3 | 73.0 | <25 | 82.4 | 76.0 | ||

| Horton (2015) | 14 | <12 | 86.6 | 70.1 | <11 | 84.5 | 69.0 | <12 | 85.6 | 72.4 | ||

| Bezdicek (2018) | 16 | <12 | 80.4 | 82.6 | <11 | 84.0 | 74.2 | <13 | 85.9 | 73.7 | ||

| Dong (2016) | 12 | <10 | 86.0 | 69.5 | <9 | 83.8 | 72.2 | <10 | 84.7 | 71.8 | ||

| Bocti (2013) | 10 | <7 | 85.8 | 72.2 | <5 | 81.1 | 77.4 | <7 | 84.0 | 75.7 | ||

| Mai (2013) | 10 | <7 | 81.3 | 79.4 | <6 | 81.9 | 76.2 | <7 | 79.2 | 82.2 | ||

MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

The optimal cut-off score is based on a balance between sensitivity and specificity, with a preference for slightly higher sensitivity to reduce the false negative rates.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the performance of the MoCA variants in discriminating dementia from non-dementia. All the short variants of MoCA had significantly lower performance than the original MoCA in discriminating dementia from non-dementia, especially among participants with >12 years of education (Supplementary Material 2). At the optimal cut-off score of <22, the original MoCA demonstrated 83.9% sensitivity and 82.9% specificity in discriminating dementia from non-dementia (Supplementary Material 3). All the MoCA variants maintained the minimally-acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity (>70%) at their respective optimal cut-off scores. Detailed results on the sensitivity and specificity statistics of each MoCA variant in identifying dementia are further presented in Supplementary Material 4.

DISCUSSION

This study provided the confirmatory evidence – using the largest sample to date in the literature related to short variants of MoCA (n=4,606) – on the comparative performance of the various short variants in the diagnosis of MCI and dementia. Although all the short variants of MoCA had acceptable diagnostic performance, only the variant by Roalf (2016)5 had comparable performance to that of the original MoCA in discriminating MCI and dementia from normal cognition even across education subgroups. In contrast, all the short variants had relatively lower performance than the original MoCA in discriminating dementia from non-dementia, albeit by small margins of difference in the AUC.

Overall, the short variant by Roalf (2016)5 presents as a viable alternative for detection of MCI and dementia when the original MoCA cannot be feasible administered in routine clinical practice. This short variant comprises 8 items – which is only one-third the length of the original MoCA – and may be completed in less than 5 minutes.5 It can be especially useful in non-specialty clinics (such as in primary care, geriatric, and stroke prevention clinics), which provide care to large volume of patients at high-risk of cognitive impairment (due to the presence of multiple risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and advancing age) but have comparatively less resources than specialized memory clinics to administer cognitive tests. Potentially, the routine administration of this short variant can have a health-systems impact – it can facilitate early detection of cognitive impairment in non-specialty clinical services and improve patients’ access to timely preventive interventions, such as those related to risk factor modifications23 and cognitive training.24 Such practice is consistent with the recent consensus recommendations by the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics, on the need for active case-finding and timely interventions for early cognitive impairment.25

It is understandable why most of the short variants of MoCA can have poorer diagnostic performance, especially among participants with higher educational attainment. Having fewer test items in the cognitive tests, the short variants may be less sensitive to more subtle changes in cognition, which can result in ceiling effects especially among those with higher education. Notwithstanding this limitation, the short variant by Roalf (2016)5 still maintained similar performance to MoCA in identifying MCI and dementia, which may possibly be explained by how this short variant was previously developed. Compared to the other short variants, the variant by Roalf (2016)5 was developed through more rigorous methods – using item response theory and simulated computerized adaptive testing in a large sample (n=1,850) – and hence allowed the selection of items within the original MoCA which are most discriminative of participants with varying cognitive function.5 Moreover, this short variant by Roalf (2016)5 also has an additional strength where its scores can be mapped to those of MMSE using a recently published conversion table.8 As such, the scores from this short variant may be easily converted to those of MMSE, which can facilitate the comparison of scores across clinical sites that administer the two different tests. Notwithstanding the strengths of this variant, one may still need to apply some caution when using it to discriminate dementia from non-dementia, considering its relatively lower performance in this respect.

Several limitations should be considered. First, the participants in this study involved those who volunteered at the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. Hence, the findings on the optimal MoCA variant are more applicable to the typical healthcare services (where patients often voluntarily present themselves), rather than community settings. Second, most of the participants who volunteered at the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers had higher educational attainment (with half of them having at least a bachelor’s degree, or 16 years of education), compared to patients in the usual clinical settings. To address this limitation, the study analyses had also been stratified by education subgroups; of which the results provided some indication that the choice of the short variant may probably be less consequential among those with lower educational attainment, as the ceiling effects (which are often evident among highly educated individuals) may possibly be less of a problem among those with lower educational attainment. Third, majority of the participants with dementia (69.3%) had the primary etiology of Alzheimer’s dementia. Although such large proportion of Alzheimer’s dementia is consistent with what is expected of the older population with dementia, the findings may not necessarily apply to participants with other primary etiologies of dementia. Fourth, in a small proportion of the participants (11.9%), the diagnoses of MCI and dementia were made primarily by single clinicians. They may not necessarily be as accurate as those made via consensus conference. Fifth, the identified short variant from this study is intended to expand the range of brief cognitive tests that clinicians can choose from in the diagnosis of cognitive impairment, and can be especially useful in clinical services which have already been familiar with the administration of MoCA. It is not intended as a replacement to the other equally-useful brief cognitive tools,25 such as the Mini-Cog26 and the Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUM) examination.27

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In conclusion, the various short variants of MoCA may not share comparable performance to the original MoCA in the diagnosis of MCI and dementia, with many limited by ceiling effects among participants with higher education. Among all, the variant by Roalf (2016)5 may be the best alternative when the original MoCA cannot be feasibly administered in clinical services with high patient load and limited resources for cognitive testing (such as in primary care, geriatric, and stroke prevention clinics).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Funding sources: TML is supported by research grants under the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (grant number NMRC/Fellowship/0030/2016 and NMRC/CSSSP/0014/2017).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacova C, Kertesz A, Blair M, Fisk JD, Feldman HH. Neuropsychological testing and assessment for dementia. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2007;3(4):299–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsoi KF, Chan JC, Hirai HW, Wong SS, Kwok TY. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(9):1450–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bezdicek O, Cervenkova M, Moore TM, et al. Determining a Short Form Montreal Cognitive Assessment (s-MoCA) Czech Version: Validity in Mild Cognitive Impairment Parkinson’s Disease and Cross-Cultural Comparison. Assessment. 2018:1073191118778896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roalf DR, Moore TM, Wolk DA, et al. Defining and validating a short form Montreal Cognitive Assessment (s-MoCA) for use in neurodegenerative disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2016;87(12):1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong A, Nyenhuis D, Black SE, et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment 5-minute protocol is a brief, valid, reliable, and feasible cognitive screen for telephone administration. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2015;46(4):1059–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horton DK, Hynan LS, Lacritz LH, Rossetti HC, Weiner MF, Cullum CM. An Abbreviated Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for Dementia Screening. The Clinical neuropsychologist. 2015;29(4):413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roalf DR, Moore TM, Mechanic-Hamilton D, et al. Bridging cognitive screening tests in neurologic disorders: A crosswalk between the short Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-Mental State Examination. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017;13(8):947–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong Y, Xu J, Chan BP, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is superior to National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke-Canadian Stroke Network 5-minute protocol in predicting vascular cognitive impairment at 1 year. BMC neurology. 2016;16:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bocti C, Legault V, Leblanc N, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment: most useful subtests of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in minor stroke and transient ischemic attack. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2013;36(3–4):154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mai LM, Oczkowski W, Mackenzie G, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in a stroke prevention clinic using the MoCA. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2013;40(2):192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, van Belle G, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Database: an Alzheimer disease database. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2004;18(4):270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen RC, Morris JC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(7):1160–1163; discussion 1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular dementia. Diagnostic criteria for research studies: Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop*. 1993;43(2):250–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litvan I, Bhatia KP, Burn DJ, et al. Movement Disorders Society Scientific Issues Committee report: SIC Task Force appraisal of clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinsonian disorders. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2003;18(5):467–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bensimon G, Ludolph A, Agid Y, Vidailhet M, Payan C, Leigh PN. Riluzole treatment, survival and diagnostic criteria in Parkinson plus disorders: the NNIPPS study. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 1):156–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013;80(5):496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other motor neuron disorders : official publication of the World Federation of Neurology, Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. 2000;1(5):293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang J-H, Xu Y, Lin L, Jia R-X, Zhang H-B, Hang L. Comparison of multiple interventions for older adults with Alzheimer disease or mild cognitive impairment: A PRISMA-compliant network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(20):e10744–e10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang J-H, Li J-Y, Jia R-X, et al. Comparison of Cognitive Intervention Strategies for Older Adults With Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease: A Bayesian Meta-analytic Review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morley JE, Morris JC, Berg-Weger M, et al. Brain health: the importance of recognizing cognitive impairment: an IAGG consensus conference. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015;16(9):731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for Detecting Dementia and Mild Neurocognitive Disorder—A Pilot Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.