Summary:

Higher prevalence of nursing home specialists was associated with regional improvements in two of the six clinical quality measures evaluated, suggesting that these specialists play an important role in nursing home care quality.

Importance:

While the number of prescribing clinicians (physicians and nurse practitioners) who provide any nursing home (NH) care remained stable over the past decade, the number of clinicians who focus their practice exclusively on NH care has increased by over 30%.

Objectives:

To measure the association between regional trends in clinician specialization in NH care and NH quality.

Design:

Retrospective cross-sectional study.

Setting and Participants:

Patients treated in 15,636 NHs in 305 U.S. hospital referral regions (HRRs) between 2013 and 2016.

Measures:

Clinician specialization in NH care for 2012-2015 was measured using Medicare fee-for-service billings. NH specialists were defined as generalist physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, geriatrics, and general practice) or advanced practitioners (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) with at least 90% of their billings for care in NHs. The number of clinicians was aggregated at the HRR level and divided by the number of occupied Medicare-certified NH beds. Nursing Home Compare quality measure scores for 2013-2016 were aggregated at the HHR level, weighted by occupied beds in each NH in the HRR. We measured the association between the number of NH specialists per 1,000 beds and the clinical quality measure scores in the subsequent year using linear regression.

Results:

An increase in NH specialists per 1,000 occupied beds in a region was associated with lower use of long-stay antipsychotic medications and indwelling bladder catheters, higher prevalence of depressive symptoms, and was not associated with urinary tract infections, use of restraints, or short-stay antipsychotic use.

Conclusions and Implications:

Higher prevalence of NH specialists was associated with regional improvements in 2 of 6 quality measures. Future studies should evaluate whether concentrating patient care among clinicians who specialize in NH practice improves outcomes for individual patients. The current findings suggest that prescribing clinicians play an important role in nursing home care quality.

Keywords: nursing home, care quality, specialization, post-acute care, hospitalization

Annually, U.S. nursing homes provide nearly 2.3 million short-stays that offer rehabilitation and skilled nursing services after hospital discharge1 and 1.4 million long-stays for patients requiring custodial care or have long-term rehabilitation or nursing needs.2 As a common discharge destination for elderly hospitalized patients, nursing homes have long been the subject of public and private initiatives that aim to improve quality of care, including stringent regulatory oversight, broad-based public reporting of quality metrics, as well as focused interventions to improve specific processes of care such as those around care transitions and clinician communication.3–6 Despite these efforts, outcomes of patients admitted to nursing homes for short- or long-term care remain highly variable across facilities.1,5,7–9

Despite emerging data suggesting that physician and other prescribing clinicians play an important role in nursing home care quality and outcomes, few interventions evaluated the effects of alternative approaches to medical staff organization within nursing homes on patient outcomes.10,11 Traditionally, community physicians ‘follow’ their patients admitted to the nursing home or contract with the nursing home, typically spending a couple hours a week in the facility,12 while the majority of their practice was spent practicing in other settings (e.g., clinic, hospital, etc). However, increasing regulatory, public reporting, and patient clinical burdens have led to calls for a more specialized physician workforce in the nursing home.13 These calls were in parallel with interventions that introduced specialized advanced practice providers (i.e., nurse practitioners) who focused their practice on the nursing home, with some evidence of a beneficial impact on quality and costs.14–17

While most physicians who see patient in nursing homes still practice under the traditional model, the number of clinicians who focus their practice on nursing home populations has been on the rise. In fact, between 2012-2015, the number of physicians and advanced practitioners who specialized in nursing home care increased by 34%.18 Whether this change in nursing home clinician organization is associated with improvements in quality is unknown. On one hand, specialization in hospital care (i.e., hospitalists) has been associated with lower readmission and mortality rates.19 On other hand, site-specific specialization may worsen outcomes through increased care fragmentation across settings.20

Our objective in this study was to measure the association between regional trends in clinician specialization in nursing home care and nursing home quality as measured by six Nursing Home Compare clinical quality measures. We hypothesized that nursing home patients in regions with more clinicians who specialize in nursing home care have better outcomes compared to patients in regions where fewer clinicians specialize in nursing home care.

Methods

Study Design

Using an ecological approach, we measured the relationship between clinician specialization in nursing home practice and regional performance on nursing home clinical quality scores. We adopted a previously used definition for nursing home specialists,18 which is analogous to the definition for hospitalists used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).21 Nursing home specialists were defined as generalist physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, geriatrics, and general practice) and advanced practitioners (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) with at least 90% of their billings for care in nursing homes. The number of clinicians was aggregated at the hospital referral region level and divided by the number of occupied Medicare-certified nursing home beds. Quality measure data for nursing homes were also aggregated at the hospital referral region level and weighted by nursing home beds. We then measured the association between quality measure rates and the number of nursing home specialists per 1,000 beds in the prior year using linear regression.

Data Sources and Study Sample

Data sources included CMS Provider and Other Supplier Public Use Files and the Nursing Home Compare annual files. The Provider Utilization Files include service-level utilization information for each clinician (including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) in the U.S. Each provider is identified by a unique National Provider Identification (NPI) code. NPIs associated with organizations were excluded from analysis. The database includes clinician information such as name, practice address (including zip code), services performed for 10 or more Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries per year (identified using HCPCS codes), and place of service codes (nursing home vs. skilled nursing facility). For 2012-2015, the Provider Utilization Files were used to measure clinician specialization in nursing home care using Medicare fee-for-service billings. The CMS Nursing Home Compare annual files were used to obtain nursing home scores on six quality measures for 2013-2016 as well as nursing home occupancy rates and Medicare-certified bed counts. The Long Term Care Focus database (ltcfocus.org22) was used to obtain nursing home characteristics (chain status, for-profit ownership status, direct care staff hours per resident day, skilled to total nurse staffing ratio, presence of physician extenders, and patient acuity index). The datasets were aggregated and linked at the hospital referral region level (using the Dartmouth Atlas geographic region definitions for hospital referral regions).

Our sample included 15,636 nursing homes in the 305 U.S. hospital referral regions between 2013 and 2016. One hospital referral region (Alaska) was missing occupancy data and was excluded from analysis.

Outcomes

The Nursing Home Compare database was used to obtain annual nursing home scores on six quality measures between 2013-2016. We selected six measures a priori deemed to be under the influence of prescribing clinicians by conducting an informal focus group composed of nurse practitioners, physicians, and a nursing home administrator. The six quality measures included in the analysis were for patients who: (1) newly received an antipsychotic medication (short-stay measure), (2) had a urinary tract infection (long-stay measure), (3) received an antipsychotic medication (long-stay measure), (4) had a catheter inserted and left in their bladder (long-stay measure), (5) were physically restrained (long-stay measure), and (6) had depressive symptoms (detected either via patient interview or staff assessment during a routine mandated patient evaluation) (long-stay measure). The following clinical measures were excluded because they were thought to relate more closely to direct care staff or rehabilitation services than to physician or advanced practitioner care: residents who self-report moderate to severe pain, new or worsened pressure ulcers, influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations, improvement in locomotion or decline in activities of daily living, and weight loss. The score for each of the six included measures was weighted by the number of occupied Medicare-certified beds in that nursing home and averaged across all nursing homes in the hospital referral region.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted at the level of the hospital referral region. Using linear regression, we modeled the relationship between regional nursing home quality measure performance score and the number of clinicians who specialized in nursing home practice per 1,000 occupied Medicare-certified nursing home beds. The specialization variable was lagged by one year. Each outcome (quality measure) was modeled separately. Other covariates included in the models were identified a priori as factors that may influence regional performance on quality measures. These variables included demographic characteristics of the nursing home resident population (age, race, sex, insurance coverage by Medicare vs. Medicaid), nursing home characteristics (chain status, for-profit ownership status, direct care staff hours per resident day, skilled to total nurse staffing ratio, presence of physician extenders, and patient acuity index), and a market level index of nursing home competition (measured using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index). Patient demographic variables were aggregated at the hospital referral region level by calculating the weighted average across nursing homes in that region, weighted by the number of total occupied beds in each nursing home. Nursing home characteristics were quantified at the hospital referral region level using percentages for categorical characteristics (e.g., chain status) and weighted averages for continuous measures (e.g., direct care staff hours per resident day). The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is a commonly used measure of market concentration, calculated as the sum of squares of occupied beds in each nursing home in the region.23 We also included year fixed effects to account for time trends.

In separate analyses, the average adjusted score for each clinical quality measure was estimated at distinct levels of nursing home clinician specialization that corresponded roughly to the deciles of nursing home clinician specialization. In other words, the performance score for each clinical quality measure was estimated for a population of nursing homes with clinical specialization in the bottom decile, setting all other independent variables to observed values. The calculation was then repeated for a population of nursing homes with clinical specialization in the next decile, 3rd decile, and so on, through the top decile of nursing home clinical specialization. Thus, the estimates were calculated using adjusted predictions at representative values (margins command in Stata).24

Additional Analyses

We performed additional analyses to examine physicians and advanced practitioners (NPs or PAs) separately. To do this, we calculated the number of specialized clinicians per 1,000 nursing home beds in each HRR separately for each of the two subgroups of clinicians. Then, we estimated the association between regional nursing home quality measure performance score and the number of physicians who specialized in nursing home practice per 1,000 occupied Medicare-certified nursing home beds. Lastly, we estimated the association between regional nursing home quality measure performance score and the number of advanced practitioners who specialized in nursing home practice per 1,000 occupied Medicare-certified nursing home beds.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.1 (College Station, TX). The study was exempt from review by the [BLINDED] Institutional Review Board.

Results

In the 305 hospital referral regions in our sample, the median number of nursing home specialists per 1,000 beds was 4.00 (interquartile range, 2.38 to 5.89). We observed 20-fold variation in nursing home clinician specialization between the hospital referral regions in the top vs. bottom deciles of specialization. The median number of nursing home specialists per 1,000 beds in the hospital referral regions in the bottom decile of specialization was 0.54 (interquartile range, 0 to 0.97), whereas the median number of nursing home specialists per 1,000 beds in the hospital referral regions in the top decile of specialization was 10.38 (interquartile range, 8.89 to 14.84).

Table 1 summarizes patient population, nursing home, and market characteristics of the hospital referral regions analyzed. The mean patient age was 79.9 years, 60.1% were female and 81.2% white. The nursing homes in general had a higher proportion of Medicaid-covered patients compared to Medicare (or other payers). On average, 45.6% of the facilities had advanced practitioners present, 56.7% were part of a chain, and 69.0% were for-profit. The average market concentration of nursing homes across the hospital referral regions was relatively low (456.0 on a scale of ~0 to 10,000, where 10,000 is a monopoly).

Table 1.

Patient, Facility, and Market Characteristics of Study Sample

| Characteristic | Mean or % | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Age (Mean) | 79.9 | 79.0 - 80.0 |

| Female (%) | 60.1 | 59.9 - 60.3 |

| White (%) | 81.2 | 80.4 - 82.0 |

| Acuity index (Mean) | 12.1 | 12.1 - 12.2 |

| Medicaid (%) | 62.4 | 62.0 - 62.8 |

| Medicare (%) | 14.7 | 14.4 - 14.9 |

| Facility Characteristics | ||

| Nurse staffing ratio (Mean) | 0.35 | 0.34 - 0.36 |

| Direct care hours per patient day (Mean) | 3.65 | 3.63 - 3.67 |

| Presence of advanced practitioners (%) | 45.6 | 44.6 - 46.7 |

| Part of a chain (%) | 56.7 | 55.8 - 57.7 |

| For-profit ownership status (%) | 69.0 | 68.1 - 70.0 |

| Market Characteristic | ||

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (Mean) | 456.0 | 437.4 - 474.8 |

Table 2 contains regional performance rates on the six clinical quality measures for 2012-2015. Overall, regional performance rates ranged from 1.20% for the use of restraints (95% CI: 1.15-1.25) to 19.09% for long-stay use of anti-psychotic medications (95% CI: 18.84-19.34). However, most of the measures had a relatively low prevalence of the adverse events, with five of the six measures’ average performance rates falling between 1.20% and 5.55%. Regional performance improved on all six measures over this time interval (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regional Performance on Nursing Home Clinical Quality Measures: 2012-2015

| Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Measure | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Overall |

| Use of anti-psychotic medications (long-stay), % | 21.57 (21.06-22.08)* | 19.64 (19.15-20.13) | 18.44 (17.98-18.89) | 16.71 (16.33-17.09) | 19.09 (18.84-19.34) |

| Use of anti-psychotic medications (short-stay), % | 2.67 (2.57-2.78) | 2.45 (2.35-2.55) | 2.30 (2.21-2.39) | 2.13 (2.04-2.21) | 2.39 (2.34-2.44) |

| Use of restraints, % | 1.73 (1.61-1.85) | 1.30 (1.20-1.40) | 1.02 (0.93-1.10) | 0.77 (0.70-0.84) | 1.20 (1.15-1.25) |

| Use of indwelling urinary catheters, % | 3.53 (3.44-3.63) | 3.16 (3.07-3.25) | 3.13 (3.04-3.22) | 2.79 (2.70-2.87) | 3.15 (3.10-3.20) |

| Residents with a urinary tract infection, % | 6.46 (6.29-6.62) | 5.70 (5.54-5.85) | 5.22 (5.07-5.37) | 4.43 (4.31-4.55) | 5.45 (5.36-5.53) |

| Residents with symptoms of depression, % | 6.09 (5.67-6.52) | 5.77 (5.29-6.24) | 5.35 (4.86-5.84) | 4.99 (4.47-5.52) | 5.55 (5.31-5.79) |

95% confidence interval

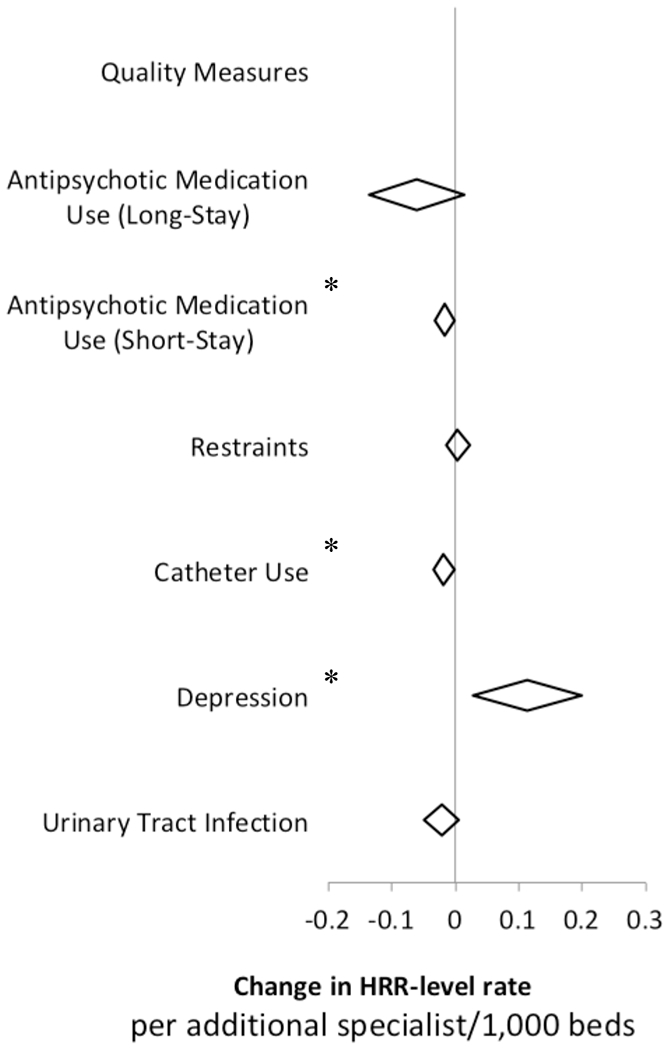

In the six NH quality measures, the presence of an additional specialist per 1,000 beds was associated with lower catheter use and antipsychotic medication use. Specifically, there was a decrease of −0.018 in the regional rate for catheter use (95% CI: −0.034 to −0.001, p=0.03) and a decrease of −0.017 in the regional rate of antipsychotic medication use for short stays (95% CI: - 0.033 to −0.001, p=0.03) (Table 3). There was an increase of 0.114 in the regional rate for residents with symptoms of depression (95% CI: 0.028 to 0.200, p=0.01) (Table 3). The association was not statistically significant for urinary tract infections, use of restraints, or long-stay antipsychotic use (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Association between Nursing Home Clinician Specialization and Regional Performance on Nursing Home Quality Measures

| Quality Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRR-level Variables | Use of anti-psychotic medications (long-term) | Use of anti-psychotic medications (short-term) | Use of restraints | Use of indwelling urinary catheters | Residents with a urinary tract infection | Residents with symptoms of depression |

| NH specialists per 1,000 beds | −0.061 (−0.136 to 0.014) | −0.017* (−0.033 to −0.001) | 0.004 (−0.014 to 0.022) | −0.018* (−0.034 to −0.001) | −0.022 (−0.049 to 0.005) | 0.114* (0.028 to 0.200) |

| Percent of NHs part of chain | 0.007 (−0.004 to 0.019) | −0.002 (−0.004 to 0.003) | −0.006* (−0.009 to −0.003) | −0.004* (−0.007 to −0.002) | 0.002 (−0.185 to 0.666) | −0.030* (−0.043 to −0.017) |

| Percent of NHs that are for-profit | 0.002 (−0.011 to 0.016) | 0.000 (−0.003 to 0.003) | −0.000 (−0.003 to 0.003) | 0.008* (0.005 to 0.011) | 0.001 (−0.005 to 0.005) | −0.040* (−0.056 to −0.024) |

| Percent of stays covered by Medicaid | −0.023 (−0.057 to 0.010) | −0.001 (−0.008 to 0.006) | 0.022* (0.014 to 0.030) | −0.034* (−0.041 to −0.027) | −0.034* (−0.046 to −0.022) | −0.041* (−0.079 to −0.003) |

| Percent of stays covered by Medicare | −0.062* (−0.119 to −0.005) | 0.010 (−0.001 to 0.022) | 0.014 (0.000 to 0.028) | −0.023* (−0.035 to −0.010) | −0.017 (−0.038 to 0.004) | 0.018 (−0.048 to 0.083) |

| Average patient age in years | −0.717* (−0.827 to −0.606) | −0.053* (−0.076 to −0.030) | −0.039* (−0.065 to −0.012) | −0.042* (−0.067 to −0.018) | −0.063* (−0.104 to −0.023) | −0.651* (−0.779 to −0.523) |

| Percent of patients who are white | 0.062* (0.042 to 0.082) | −0.002 (−0.006 to 0.002) | 0.006* (0.001 to 0.011) | 0.014* (0.010 to 0.019) | 0.027* (0.020 to 0.034) | 0.059* (0.036 to 0.082) |

| Percent of patients who are female | −0.091* (−0.169 to −0.012) | 0.010 (−0.007 to 0.026) | 0.041* (0.022 to 0.060) | −0.010 (−0.028 to 0.007) | 0.084* (0.055 to 0.113) | −0.083 (−0.174 to 0.008) |

| RN to total staffing ratio | −0.081* (−0.098 to −0.065) | −0.020* (−0.024 to −0.017) | −0.008* (−0.012 to −0.004) | 0.003 (−0.000 to 0.007) | −0.018* (−0.024 to −0.012) | 0.083* (0.064 to 0.102) |

| Direct care staff hours per patient day | −3.477* (−4.115 to −2.839) | −0.737* (−0.870 to −0.604) | 0.206* (0.052 to 0.359) | 0.016 (−0.125 to 0.158) | −0.302* (−0.535 to −0.069) | −4.861* (−5.595 to −4.127) |

| Percent of NHs with APPs (e.g., NPs) | 0.015* (0.003 to 0.027) | 0.005* (0.002 to 0.007) | 0.002 (−0.001 to 0.005) | −0.008* (−0.011 to −0.005) | 0.004 (−0.001 to 0.008) | 0.005 (−0.008 to 0.019) |

| Average patient acuity index | −0.465* (−0.908 to −0.023) | 0.096* (0.003 to 0.188) | 0.248* (0.141 to 0.354) | 0.016 (−0.083 to 0.011) | 0.437* (0.275 to 0.599) | −0.124 (−0.633 to 0.385) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of NHs in HRR | 1.242 (−4.628 to 7.111) | −0.674 (−1.896 to 0.548) | 2.153* (0.739 to 3.567) | 1.940* (0.639 to 3.241) | 0.849 (−1.298 to 2.997) | −2.500 (−9.256 to 4.256) |

| Year: 2014 | −1.756* (−2.269 to −1.242) | −0.200* (−0.307 to −0.094) | −0.451* (−0.575 to −0.328) | −0.368* (−0.482 to −0.254) | −0.769* (−0.957 to −0.581) | −0.280 (−0.871 to 0.310) |

| Year: 2015 | −2.937* (−3.462 to −2.412) | −0.331* (−0.440 to −0.221) | −0.713* (−0.839 to −0.586) | −0.376* (−0.492 to −0.259) | −1.197* (−1.389 to −1.005) | −0.829* (−1.433 to −0.225) |

| Year: 2016 | −4.832* (−5.373 to −4.291) | −0.516* (−0.629 to −0.404) | −0.940* (−1.070 to −0.810) | −0.704* (−0.824 to −0.584) | −1.983* (−2.181 to 1.785) | −1.314* (−1.936 to −0.691) |

p-value < 0.05

Abbreviations: HHR – Hospital Referral Region, NH – Nursing Home

Figure 1:

Regional Nursing Home Quality Measure Performance for Six Measures under Prescribing Clinician Control

*P<0.05

In subgroup analyses, regions with higher rates of nursing home specialists who were physicians were associated with lower catheter use (coefficient: −0.068, 95% CI: −0.106 to −0.030, p<0.01) and antipsychotic medication use for both long-stay (coefficient: −0.562, 95% CI: −0.730 to - 0.393, p<0.01) and short-stay residents (coefficient: −0.017, 95% CI: −0.033 to −0.001, p<0.01) (Appendix Figure 1 and Table 1). Higher prevalence of nursing home specialists who were advanced practitioners was associated with lower rates of residents with urinary tract infection (coefficient: −0.041, 95% CI: −0.075 to −0.007, p=0.02), but higher rates of residents with symptoms of depression (coefficient: 0.159, 95% CI: 0.051 to 0.266, p<0.01) (Appendix Figure 2 and Table 2).

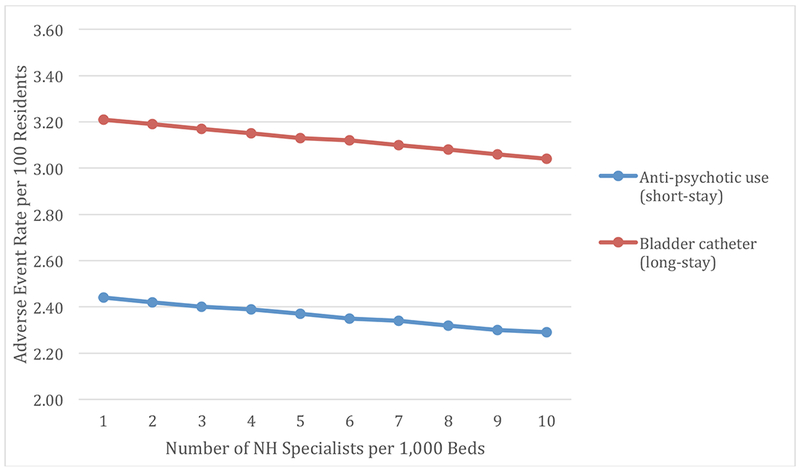

Figure 2 displays the average adjusted adverse event rate per 100 nursing home residents by the regional level of nursing home clinician specialization (in specialists per 1,000 beds). Compared to regions in the highest decile of nursing home clinician specialization (approximately 10 nursing home specialists per 1,000 beds), regions in the bottom decile of nursing home clinician specialization (approximately 1 nursing home specialist per 1,000 beds) had 5% more antipsychotic medication use events for short-stay patients and 6% more long-stay residents with indwelling bladder catheters.

Figure 2:

Adverse Event Rate per 100 Residents by Level of Nursing Flome Clinician Specialization

Discussion

The recent trends in increased physician and advanced practitioner specialization in nursing home practice appear to correlate with improved performance on two of the six the nursing home quality measures evaluated. When comparing regions in the bottom vs. top decile of nursing home clinician specialization, the observed differences represent about 5% fewer short-stay nursing home patients on anti-psychotic medications and 6% fewer patients with indwelling catheters in the regions in the top decile of clinician specialization. Nevertheless, the relative influence of specialization on performance was relatively small compared to some of the other nursing home factors (e.g., direct care staff hours). And it is important to note that the net effect is relatively small for a population of over 3 million nursing home residents annually and may be confounded by other unobserved changes in nursing home medical staff organization or processes of care occurring simultaneously in the regions with more clinician specialization.

Three of the measures were not statistically significantly associated with nursing home clinician specialization. One possible explanation is that baseline prevalence of the adverse events evaluated by the quality measures is relatively low. There may be a “floor effect” with respect to possible improvement in care quality in these areas. Furthermore, estimates of nursing home quality aggregated at the regional level may obscure important variation in performance (e.g., at smaller facilities in regions with many nursing homes). Lastly, we observed a positive association between advanced practitioner specialization and the rate of depressive symptoms. While this clinical quality measure aims to bring attention to residents’ mood and improve treatment of depressive symptoms, it is also possible that poorly performing facilities under-diagnose or under-report depressive symptoms.

One mechanism by which more specialized clinicians may enable nursing homes to achieve better scores on the quality measures could be by being more available to direct care staff and administrators as well as to patients and their families. Our definition of clinician specialization using clinician practice patterns of services performed in nursing homes over all other settings means that these clinicians almost exclusively practice in nursing homes. Previous studies found that unavailability of clinicians to assess patients and discuss options with family was cited as one of the top reasons for hospitalizations of elderly patients from nursing homes for potentially burdensome care.25 Future studies should evaluate whether more specialized clinicians practice in the same nursing home or in multiple facilities. Through closer partnership with nursing homes, specialized clinicians may develop a better understanding of nursing home processes of care, closer working relationships with staff and administrators, and become more skilled at navigating logistics that may be unique to those facilities. These skills may improve patient experience and outcomes of nursing home care. Not surprisingly, qualitative interviews of physicians who practice in the nursing home found that caring for a population with high social needs requires additional time and “good social practice”, meaning close working professional relationships with staff and patients and their families.26

Specialized care in nursing home requires knowledge of setting-specific regulations as well as unique clinical needs and behavioral concerns of this high-risk patient population. For example, a study of U.S. nursing homes found that over half of residents receiving antipsychotics did not have an approved indication for that therapy.27 Unique clinical needs of long-term nursing home patients may include other complex comorbidities such as mental illness requiring custodial care.28 Beyond unique clinical expertise, clinicians practicing in nursing home face time requirements that are greater compared to other settings.29 Many aspects of care provided in the nursing home including goals of care discussions, managing complex behavioral concerns, and dementia care require more face-to-face time with patients and families. Understanding and negotiating patient preferences has been identified in prior research as an important factor in patient satisfaction with nursing home care.30 Future research should evaluate whether patient and caregiver expectations and experiences with care differ under the care of clinicians who specialize in nursing home practice vs. those who do not.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies that found positive effects of clinician specialization, albeit those studies were limited to a small number of facilities, focused on training and certification rather than actual practice patterns, and did not include both physician and nurse practitioners. For example, facilities with certified medical directors had higher quality scores compared to facilities without certified medical directors.31 Other studies reported that an increase in nurse practitioners that exclusively cared for elderly patients was associated with better patient outcomes.32,33 This correlation was also observed when specialized nurse practitioners were substituted for physicians in long-term care.34 Although our main findings appear to be driven by nursing home specialists who are physicians, higher prevalence of advanced practitioners who specialized in nursing home care was associated with better performance on one of the six measures.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the use of an ecologic study design limits inferences regarding causality. Second, there may be unobserved patient, region, market, and nursing home characteristics that confound the relationship between nursing home clinician specialization and regional performance on nursing home quality measures. For example, nursing homes that concentrate the care of their patients among clinicians who specialize in nursing home care may have better work culture. Multiple studies found that work culture among healthcare personnel in nursing homes, including supportive management and leadership style, is associated with improved quality of care.35 Future studies should evaluate the relationship between patient volume and outcomes in this setting.36 In addition, regions with high clinician specialization may be uniquely different from other regions. Third, some of the included measures may not be under prescribing clinician control, whereas some of the excluded measures may be under the control of prescribing clinicians (e.g., vaccinations). However, this measurement error would bias the result toward no effect. Fourth, the Provider and Other Supplier Public Use Files aggregate services provided at the clinician-service code level. Therefore, we were unable to link physician practice information to specific nursing homes which precluded analysis at the level of individual nursing homes rather than HRRs, possibly obscuring variation across facilities.

Conclusions and Implications

Higher prevalence of nursing home specialists was associated with regional improvements in two of six quality measures. Future studies should evaluate whether nursing homes that concentrate patient care among clinicians who specialize in nursing home practice achieve better patient outcomes for individual patients. The current findings suggest that prescribing clinicians play an important role in nursing home care quality and support future experimentation with nursing home care specialists as a strategy to improve post-acute care outcomes by health systems transitioning from fee-for-service to value-based payment models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The findings of this study were presented during the nursing home quality podium session at the annual research meeting of the American Geriatrics Society on May 3, 2018 in Orlando, FL.

Funding: [BLINDED] work on this study was supported by the NIA Career Development Award ([BLINDED]).

APPENDIX Table 1.

Association between Nursing Home Physician Specialization and Regional Performance on Nursing Home Quality Measures: Subgroup Analysis

| Quality Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRR-level Variables | Use of anti-psychotic medications (long-term) | Use of anti-psychotic medications (short-term) | Use of restraints | Use of indwelling urinary catheters | Residents with a urinary tract infection | Residents with symptoms of depression |

| NH specialist physicians/1,000 beds | −0.562* (−0.730 to −0.393) | −0.087* (−0.122 to −0.051) | −0.010 (−0.051 to 0.031) | −0.068* (−0.106 to −0.030) | 0.024 (−0.038 to 0.087) | 0.059 (−0.138 to 0.257) |

| Percent of NHs part of chain | 0.006 (−0.006 to 0.017) | −0.002 (−0.005 to 0.001) | −0.006* (−0.009 to −0.003) | −0.004* (−0.007 to −0.002) | 0.003 (−0.002 to 0.007) | −0.031* (−0.044 to −0.018) |

| Percent of NHs that are for-profit | 0.003 (−0.010 to 0.016) | 0.000 (−0.003 to 0.003) | −0.001 (−0.003 to 0.003) | 0.008* (0.005 to 0.011) | 0.001 (−0.005 to 0.005) | −0.040* (−0.055 to −0.024) |

| Percent of stays covered by Medicaid | −0.018 (−0.051 to 0.015) | −0.000 (−0.007 to 0.007) | 0.022* (0.014 to 0.030) | −0.033* (−0.041 to −0.026) | −0.034* (−0.047 to −0.022) | −0.042* (−0.080 to −0.003) |

| Percent of stays covered by Medicare | −0.057* (−0.112 to −0.002) | 0.010 (−0.001 to 0.022) | 0.015* (0.001 to 0.028) | −0.023* (−0.036 to −0.011) | −0.021 (−0.041 to 0.001) | 0.030 (−0.035 to 0.095) |

| Average patient age in years | −0.708* (−0.817 to −0.599) | −0.053* (−0.075 to −0.030) | −0.038* (−0.065 to −0.011) | −0.043* (−0.067 to −0.018) | −0.067* (−0.107 to −0.026) | −0.639* (−0.767 to −0.511) |

| Percent of patients who are white | 0.057* (0.038 to 0.077) | −0.003 (−0.007 to 0.001) | 0.005* (0.001 to 0.010) | 0.014* (0.010 to 0.019) | 0.028* (0.021 to 0.035) | 0.055* (0.032 to 0.078) |

| Percent of patients who are female | −0.108* (−0.185 to −0.030) | 0.007 (−0.010 to 0.023) | 0.041* (0.022 to 0.060) | −0.013 (−0.030 to 0.004) | 0.083* (0.054 to 0.112) | −0.075 (−0.166 to 0.016) |

| RN to total staffing ratio | −0.068* (−0.085 to −0.052) | −0.019* (−0.022 to −0.015) | −0.007* (−0.011 to −0.003) | 0.004* (0.001 to 0.008) | −0.020* (−0.026 to −0.014) | 0.088* (0.068 to 0.107) |

| Direct care staff hours per patient day | −3.158* (−3.794 to −2.523) | −0.692* (−0.825 to −0.558) | 0.214* (0.058 to 0.369) | 0.049 (−0.094 to 0.192) | −0.329* (−0.566 to −0.093) | −4.837* (−5.582 to −4.091) |

| Percent of NHs with APPs (e.g., NPs) | 0.016* (0.006 to 0.027) | 0.005* (0.002 to 0.007) | 0.002 (−0.001 to 0.005) | −0.009* (−0.011 to −0.006) | 0.002 (−0.002 to 0.006) | 0.013* (0.001 to 0.025) |

| Average patient acuity index | −0.422 (−0.857 to 0.014) | 0.103* (0.011 to 0.194) | 0.248* (0.142 to 0.355) | 0.022 (−0.076 to 0.120) | 0.438* (0.275 to 0.600) | −0.137 (−0.648 to 0.374) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of NHs in HRR | −0.211 (−5.963 to 5.540) | −0.814 (−2.022 to 0.394) | 2.075* (0.666 to 3.484) | 1.882* (0.590 to 3.174) | 1.185 (−0.956 to 3.326) | −3.536 (−10.283 to 3.211) |

| Year: 2014 | −1.769* (−2.274 to −1.264) | −0.203* (−0.309 to −0.097) | −0.451* (−0.575 to −0.328) | −0.371* (−0.484 to −0.257) | −0.771* (−0.959 to −0.583) | −0.267 (−0.860 to 0.325) |

| Year: 2015 | −2.956* (−3.472 to −2.440) | −0.336* (−0.444 to −0.228) | −0.711* (−0.838 to −0.585) | −0.382* (−0.498 to 0.266) | −1.205* (−1.397 to −1.013) | −0.788* (−1.393 to −0.183) |

| Year: 2016 | −4.844* (−5.375 to −4.313) | −0.522* (−0.634 to −0.411) | −0.938* (−1.068 to −0.808) | −0.711* (−0.831 to −0.592) | −1.996* (−2.194 to −1.798) | −1.254* (−1.877 to −0.632) |

p-value < 0.05

APPENDIX Table 2.

Association between Nursing Home Advanced Practitioner Specialization and Regional Performance on Nursing Home Quality Measures: Subgroup Analysis

| Quality Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRR-level Variables | Use of anti-psychotic medications (long-term) | Use of anti-psychotic medications (short-term) | Use of restraints | Use of indwelling urinary catheters | Residents with a urinary tract infection | Residents with symptoms of depression |

| NH specialist APs per 1,000 beds | 0.073 (−0.021 to 0.166) | −0.001 (−0.020 to 0.019) | 0.009 (−0.014 to 0.031) | −0.008 (−0.028 to 0.013) | −0.041* (−0.075 to −0.007) | 0.159* (0.051 to 0.266) |

| Percent of NHs part of chain | 0.008 (−0.003 to 0.020) | −0.002 (−0.004 to 0.001) | −0.006* (−0.009 to −0.003) | −0.004* (−0.007 to −0.002) | 0.002 (−0.002 to 0.007) | −0.030* (−0.044 to −0.017) |

| Percent of NHs that are for-profit | 0.002 (−0.012 to 0.016) | −0.000 (−0.003 to 0.003) | −0.000 (−0.003 to 0.003) | 0.007* (0.004 to 0.011) | 0.001 (−0.005 to 0.005) | −0.040* (−0.056 to −0.024) |

| Percent of stays covered by Medicaid | −0.022 (−0.057 to 0.011) | −0.001 (−0.008 to 0.006) | 0.022* (0.014 to 0.030) | −0.034* (−0.041 to −0.027) | −0.035* (−0.047 to −0.022) | −0.039* (−0.078 to −0.001) |

| Percent of stays covered by Medicare | −0.077* (−0.134 to −0.020) | 0.008 (−0.004 to 0.020) | 0.013 (−0.000 to 0.027) | −0.024* (−0.037 to −0.011) | −0.016 (−0.037 to 0.005) | 0.016 (−0.050 to 0.081) |

| Average patient age in years | −0.731* (−0.842 to −0.620) | −0.055* (−0.078 to −0.032) | −0.039* (−0.066 to −0.012) | −0.044* (−0.068 to −0.019) | −0.062* (−0.103 to −0.022) | −0.652* (−0.780 to −0.525) |

| Percent of patients who are white | 0.066* (0.047 to 0.086) | −0.002 (−0.006 to 0.003) | 0.006* (0.001 to 0.011) | 0.015* (0.011 to 0.019) | 0.027* (0.019 to 0.034) | 0.059* (0.036 to 0.082) |

| Percent of patients who are female | −0.100* (−0.179 to −0.021) | 0.009 (−0.008 to 0.025) | 0.041* (0.022 to 0.060) | −0.011 (−0.028 to 0.007) | 0.086* (0.057 to 0.115) | −0.090 (−0.181 to 0.001) |

| RN to total staffing ratio | −0.087* (−0.103 to −0.070) | −0.021* (−0.025 to −0.018) | −0.008* (−0.012 to −0.004) | 0.002 (−0.001 to 0.006) | −0.018* (−0.024 to −0.012) | 0.085* (0.066 to 0.104) |

| Direct care staff hours per patient day | −3.503* (−4.140 to −2.866) | −0.746* (−0.879 to −0.613) | 0.208* (0.055 to 0.362) | 0.006 (−0.135 to 0.147) | −0.318* (−0.550 to −0.085) | −4.786* (−5.518 to −4.053) |

| Percent of NHs with APPs (e.g., NPs) | 0.006 (−0.006 to 0.018) | 0.004* (0.001 to 0.006) | 0.002 (−0.001 to 0.005) | −0.009* (−0.011 to −0.006) | 0.005* (0.001 to 0.009) | 0.004 (−0.010 to 0.017) |

| Average patient acuity index | −0.449* (−0.892 to −0.006) | 0.097* (0.005 to 0.189) | 0.249* (0.142 to 0.356) | 0.016 (−0.082 to 0.114) | 0.433* (0.271 to 0.595) | −0.109 (−0.619 to 0.400) |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index of NHs in HRR | 2.443 (−3.407 to 8.294) | −0.490 (−1.710 to 0.731) | 2.175* (0.766 to 3.584) | 2.084* (0.785 to 3.383) | 0.793 (−1.344 to 2.931) | −2.608 (−9.337 to 4.120) |

| Year: 2014 | −1.771* (−2.284 to −1.257) | −0.202* (−0.309 to −0.095) | −0.452* (−0.576 to −0.328) | −0.369* (−0.483 to −0.255) | −0.766* (−0.954 to −0.579) | −0.287 (−0.878 to 0.303) |

| Year: 2015 | −2.985* (−3.510 to −2.460) | −0.336* (−0.446 to −0.227) | −0.714* (−0.841 to −0.588) | −0.379* (−0.496 to −0.263) | −1.190* (−1.382 to −0.999) | −0.844* (−1.448 to −0.240) |

| Year: 2016 | −4.901* (−5.443 to −4.360) | −0.525* (−0.638 to −0.412) | −0.942* (−1.073 to −0.812) | −0.710* (−0.830 to −0.590) | −1.974* (−2.172 to −1.776) | −1.332* (−1.955 to −0.709) |

p-value < 0.05

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris-Kojetin LSM, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States: Data From the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Health Stat. 2016;3(38). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colon-Emeric CS, Corazzini K, McConnell ES, et al. Effect of Promoting High-Quality Staff Interactions on Fall Prevention in Nursing Homes: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1634–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane RL, Huckfeldt P, Tappen R, et al. Effects of an Intervention to Reduce Hospitalizations From Nursing Homes: A Randomized Implementation Trial of the INTERACT Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1257–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryskina KL, Konetzka RT, Werner RM. Association Between 5-Star Nursing Home Report Card Ratings and Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018787323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima JC, Intrator O, Wetle T. Physicians in Nursing Homes: Effectiveness of Physician Accountability and Communication. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman M, McHugh J, Gozalo PL, Ackerly DC, Mor V. The Contribution of Skilled Nursing Facilities to Hospitals’ Readmission Rate. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):656–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas KS, Rahman M, Mor V, Intrator O. Influence of hospital and nursing home quality on hospital readmissions. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(11):e523–531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shield R, Rosenthal M, Wetle T, Tyler D, Clark M, Intrator O. Medical staff involvement in nursing homes: development of a conceptual model and research agenda. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33(1):75–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz PR, Karuza J, Intrator O, et al. Medical staff organization in nursing homes: scale development and validation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(7):498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovink MH, van Vught A, Persoon A, Schoonhoven L, Koopmans R, Laurant MGH. Skill mix change between general practitioners, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and nurses in primary healthcare for older people: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz PR, Karuza J, Intrator O, Mor V. Nursing home physician specialists: a response to the workforce crisis in long-term care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):411–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christian R, Baker K. Effectiveness of Nurse Practitioners in nursing homes: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2009;7(30):1333–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurant M, Harmsen M, Wollersheim H, Grol R, Faber M, Sibbald B. The impact of nonphysician clinicians: do they improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care services? Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(6 Suppl):36S–89S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilpatrick K, Reid K, Carter N, et al. A Systematic Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of Clinical Nurse Specialists and Nurse Practitioners in Inpatient Roles. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2015;28(3):56–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin-Misener R, Donald F, Wickson-Griffiths A, et al. A mixed methods study of the work patterns of full-time nurse practitioners in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(9-10):1327–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryskina KL, Polsky D, Werner RM. Physicians and Advanced Practitioners Specializing in Nursing Home Care, 2012-2015. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2040–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P, Showstack J, Baron RB, Goldman L. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willett LL, Landefeld CS. The Costs and Benefits of Hospital Care by Primary Physicians: Continuity Counts. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo YF, Nattinger AB. Association of Hospitalist Years of Experience With Mortality in the Hospitalized Medicare Population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.“Shaping Long Term Care in America Project at Brown University funded in part by the National Institute on Aging (1P01AG027296).”

- 23.Hirschman AO. The Paternity of an Index. The American Economic Review. 1964;54(5):761–762. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams R Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. 2012;12(2):308–331. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen AB, Knobf MT, Fried TR. Avoiding Hospitalizations From Nursing Homes for Potentially Burdensome Care: Results of a Qualitative Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):137–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee A, James R, McGregor M, Lexchin J. Nursing Home Physicians Discuss Caring for Elderly Residents: An Exploratory Study. Can J Aging. 2018;37(2):133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucas JA, Chakravarty S, Bowblis JR, et al. Antipsychotic medication use in nursing homes: a proposed measure of quality. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(10):1049–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman M, Grabowski DC, Intrator O, Cai S, Mor V. Serious mental illness and nursing home quality of care. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(4):1279–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caprio TV, Karuza J, Katz PR. Profile of physicians in the nursing home: time perception and barriers to optimal medical practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(2):93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bangerter LR, Heid AR, Abbott K, Van Haitsma K. Honoring the Everyday Preferences of Nursing Home Residents: Perceived Choice and Satisfaction With Care. Gerontologist. 2017;57(3):479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland FN, Cowles M, Dickstein C, Katz PR. Impact of medical director certification on nursing home quality of care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(6):431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavez KS, Dwyer AA, Ramelet AS. International practice settings, interventions and outcomes of nurse practitioners in geriatric care: A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;78:61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Intrator O, Miller EA, Gadbois E, Acquah JK, Makineni R, Tyler D. Trends in Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Practice in Nursing Homes, 2000-2010. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1772–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lovink MH, Persoon A, Koopmans R, Van Vught A, Schoonhoven L, Laurant MGH. Effects of substituting nurse practitioners, physician assistants or nurses for physicians concerning healthcare for the ageing population: a systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(9):2084–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andre B, Sjovold E, Rannestad T, Ringdal GI. The impact of work culture on quality of care in nursing homes--a review study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(3):449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz PR, Pfeil LA, Evans J, Evans M, Sobel H. Determining the Optimum 430 Physician-to-Resident Ratio in the Nursing Home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(12):1087–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.