Abstract

Objective:

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is associated with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and pulmonary hypertension (PH). We sought to determine prevalence, characteristics, treatment, and outcomes for subjects with PH in a SSc-associated ILD (SSc-ILD) cohort.

Methods:

Subjects with SSc-ILD on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) were included in a prospective observational cohort. Subjects had been screened for PH based on a standardized screening algorithm and underwent right heart catheterization (RHC), if indicated. PH classification was based on hemodynamics and extent of ILD on HRCT. Summary statistics and survival using Kaplan Meier method were calculated.

Results:

Ninety-three subjects with SSc-ILD were included; 76% were female, 65.6% had diffuse SSc, mean age was 54.9 years, and mean SSc disease duration was 8 years. Twenty-nine subjects (31.2%) had RHC proven PH; of those 29 subjects, 24.1% had PAH, 55.2% had WHO Group III PH, 34.5% had WHO Group III PH with pulmonary vascular resistance > 3.0 Wood units, 48.3% had PH diagnosis within 7 years of SSc onset, 82.8% were treated with ILD therapy, and 82.8% were treated with PAH therapy. Survival rate at 3 years after SSc-ILD diagnosis for all subjects was 97%. Survival rate for those with SSc-ILD and PH at 3 years after PH diagnosis was 91%.

Conclusion:

In a large SSc-ILD cohort, a significant proportion of patients have coexisting PH, which often occurs early after diagnosis; most patients were treated with ILD and PAH therapies, and survival was good. Patients with SSc-ILD should be evaluated for coexisting PH.

INTRODUCTION:

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) can be a devastating multi-organ system autoimmune disease. It can affect the skin, peripheral vasculature, muscles, joints, tendons, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and heart through fibrosis, vascular damage and immune dysregulation. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) are the leading causes of mortality in SSc [1, 2].

ILD is present in up to 90% of patients with SSc according to high resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and clinically significant ILD is present in approximately 40% of patients with SSc [3, 4]. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is also common in SSc, and patients with SSc can have various types of PH. Three common types of PH in patients with SSc include the following: WHO Group I PH (PAH), WHO Group II PH (PH due to left heart disease), and WHO Group III PH (PH due to ILD). However, in observational cohorts of SSc, which are enriched for at-risk or early PH, the majority of patients are diagnosed with PAH and a lower proportion are being identified as WHO Group II PH or WHO Group III PH [5, 6]. For example, in the PHAROS study, approximately 69% of patients with PH were classified as PAH, 10% of patients were classified as WHO Group II PH, and 21% of patients were classified as WHO Group III PH [5]; and in the DETECT study, which recruited patients at high-risk for PH, approximately 60% of subjects with PH were classified as PAH, 21% of subjects were classified as WHO Group II PH, and 19% of subjects were classified as WHO Group III PH [6].

Although previous studies have analyzed patients with concomitant SSc-ILD and PH, to our knowledge, there is lack of in depth review of the clinical characteristics and management of PH in patients with established SSc-associated ILD (SSc-ILD). This is an essential clinical question as worsening dyspnea in a patient with underlying ILD may represent progressive ILD, new onset PH, or a combination of both. In addition, many ongoing clinical trials are specifically recruiting patients with SSc-ILD, particularly for the evaluation of new and existing pharmacologic therapies for treatment of ILD; hence, it is imperative to recognize the prevalence of PH with concomitant ILD in SSc and its impact on clinical course, outcome measures, such as dyspnea and quality of life, and survival. This prompted us to investigate the prevalence of PH in a well-characterized cohort of SSc-ILD, and to explore the clinical characteristics, pharmacologic therapies, and outcomes of subjects with PH in a well-characterized cohort of SSc-ILD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and Subjects.

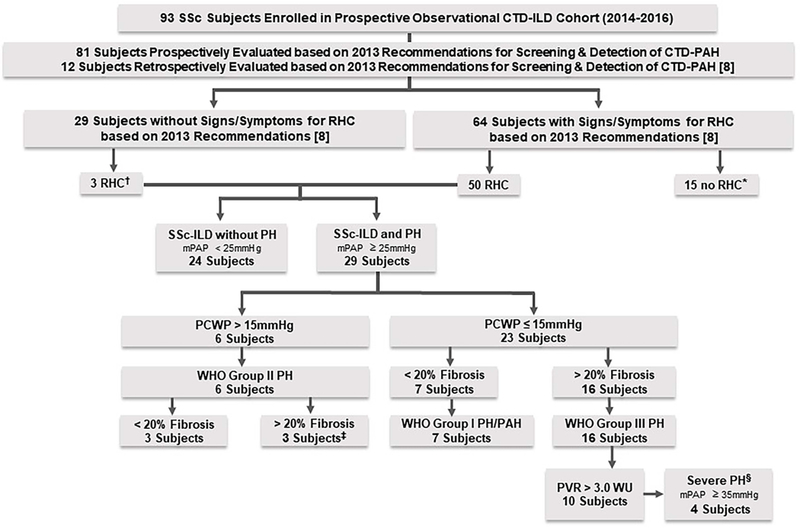

Subjects evaluated in this study were participants in a SSc-ILD prospective observational cohort study (Figure 1). Subjects were recruited from University of Michigan Scleroderma and Connective Tissue Disease (CTD)-ILD clinics starting January 8, 2014 and data was extracted on October 1, 2016. Subjects who were at least 18 years of age, met the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for SSc [7], had ILD on HRCT, and could provide informed consent were consented for the study, which was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All subjects in this study had a baseline HRCT confirming the presence of ILD defined by the presence of bilateral, subpleural, lower lobe predominant distribution of either: 1) reticular and/or ground glass opacity with or without traction bronchiectasis, or 2) honeycombing with the absence of a pattern that is predominantly nodular, cystic, peribronchovascular/central or upper lung predominant, mosaic attenuation, or consolidation. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) were obtained at baseline for each subject; subjects with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio of less than 0.7 were excluded to rule out subjects with concomitant obstructive pulmonary disease. Demographics and additional clinical variables were obtained for each subject.

Figure 1. Study Design and Characterization of PH in SSc-ILD Cohort.

* Seven referred to cardiology, but no RHC as low likelihood of PH based on evidence; 2 refused RHC; 1 lost to follow up; 2 had negative RHC after data analysis; 2 had TTE findings normalize; 1 with stable lower DLCO, normal NTproBNP and no PAH findings on TTE.

†Two underwent RHC due to severe symptoms, which was negative, and 1 underwent RHC due to decline in DLCO and had WHO Group III; none had variables required to calculate DETECT scores.

‡ One subject also had combined post-capillary and pre-capillary PH (PCWP >15mmHg and diastolic PAP – PCWP ≥ 7mmHg) according to Vachiery et al [11] and had features of chronic thromboembolic disease based on pulmonary artery angiogram.

§ SSc-ILD with PH due to ILD who have severe PH based on mPAP ≥ 35mmHg on RHC according to Seeger et al. [12].

PH-pulmonary hypertension; PAH –pulmonary arterial hypertension; SSc-systemic sclerosis; ILD-interstitial lung disease; SSc-ILD-systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease; CTD-connective tissue disease; I/E –inclusion/exclusion; RHC –right heart catheterization; mPAP –mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PCWP-pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; WHO-World Health Organization; PVR –pulmonary vascular resistance; WU-woods units; DLCO-diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide.

All patients in University of Michigan Scleroderma and CTD-ILD clinics undergo screening for PH based on the 2013 recommendations for screening and detection of CTD-associated PAH by Khanna et al., which also includes the DETECT algorithm [8]. Although the DETECT algorithm is validated in patients with a disease duration of > 3 years and DLCO < 60%, we utilize it for all SSc patients with uncorrected DLCO ≤ 80% [6]. We performed a chart review for all subjects in this SSc-ILD cohort to determine which subjects had criteria concerning for PH based on the 2013 recommendations and who had underwent a right heart catheterization (RHC) during their SSc disease course. Within this SSc-ILD cohort, the 2013 recommendations for screening and detection of CTD-associated PAH by Khanna et. al were prospectively applied to 81 subjects during their routine clinical care (Supplementary Table 1), and 12 subjects in this SSc-ILD cohort who had underwent RHC prior to 2013 had the recommendations applied retrospectively (Supplementary Table 2) [8]. A total of 53 subjects within this SSc-ILD cohort had underwent RHC; if subjects had PH on RHC, which was defined as a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) of ≥ 25mmHg, they were described in this study as subjects with “SSc-ILD and PH”, and if subjects did not meet the 2013 recommendations or had a mPAP of < 25mmHg on RHC, they were described in this study as “SSc-ILD without PH.” Those subjects with SSc-ILD and PH had a HRCT reviewed by a chest radiologist (DV) to determine ILD severity based on Goh’s criteria of < 20% extent of ILD on HRCT being considered as minimal ILD and > 20% extent of ILD on HRCT being considered as moderate-to-severe [9, 10]. The HRCT scans chosen for review were the scans closest to the diagnostic RHC (one subject’s HRCT images were not available for review, so a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram was reviewed, and another subject did not have any images available at our institution for review, so ILD type and severity was based on an external radiologist’s initial report).

Classification of PH.

Subjects classified as WHO Group I PH/ PAH had a mPAP ≥ 25mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤ 15mmHg, and < 20% extent of ILD on HRCT [10–12]. Subjects classified as WHO Group II PH had a mPAP ≥ 25mmHg and PCWP > 15mmHg. Subjects classified as WHO Group III PH had a mPAP ≥ 25mmHg, PCWP ≤ 15mmHg, and > 20% extent of ILD on HRCT [10–12]; of those subjects with WHO Group III PH, those with a mPAP ≥ 35mmHg were further classified as severe PH based on the recommendations by Seeger et al [13] (Figure 1).

Statistical Analysis.

Descriptive statistics for the overall SSc-ILD cohort, subjects with SSc-ILD without PH and subjects with SSc-ILD and PH, were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables. The differences between the subject groups without PH and with PH were compared using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate time until patient death in the overall SSc-ILD cohort and in the subset of those with SSc-ILD and PH or censored at October 1, 2016. The log-rank test was used to determine if there was a statistically significant difference in survival time in subjects with SSc-ILD and PH versus those with SSc-ILD without PH. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to determine if race (non-Hispanic white vs non-white) and age predict survival in both subsets.

To evaluate whether there was a significant trend over time in FVC and DLCO for the PFTs collected in the prospective observational cohort, a linear mixed effects model with a fixed effect for time (continuous, in months) and a random effect for the subject was used to predict change from baseline for both FVC and DLCO.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) statistical software and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of Total Cohort

A total of 93 subjects with SSc-ILD were evaluated in this study; subjects within this study had an average of 3.2 (SD ± 3.6) years from ILD diagnosis to study enrollment. Most subjects were white (84.9%), female (76.3%), non-Hispanic (88.2%) and had diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) (65.6%). The overall SSc disease duration for all cohort subjects from initial non-Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) sign/symptom was 7.9 (SD ± 7.2) years. The average diagnosis of ILD after initial non-RP sign/symptom was after 4.7 (SD ± 6.4) years. Mean modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS) was 9.4 (SD ± 9.5). The most common ILD pattern on HRCT was non-specific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP; 90.3%). PFTs at ILD diagnosis revealed a FVC % predicted of 76.2 (SD ± 15.7), TLC % predicted of 83.0 (SD ± 16.3; N=66), DLCO % predicted of 58.3 (SD ± 20.3; N=85) (4 subjects had DLCO attempted without success, 2 patients were ill, and 2 patients did not have DLCO ordered with PFTs at time of ILD diagnosis), and FVC% predicted/ DLCO% predicted of 1.5 (SD ± 0.8; N=85) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of SSc-ILD Cohort

| Baseline Characteristics | All Subjects (N=93) | SSc-ILD without PH (N=64) | SSc-ILD and PH (N=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Initial Non-RP Sign/Symptom, mean ± SD years | 46.9 ± 13.3 | 45.2 ± 13.2 | 50.9 ± 12.8 | 0.054 |

| Age at ILD Diagnosis, mean ± SD years | 51.6 ± 12.2 | 49.7 ± 11.8 | 55.8 ± 12.1 | 0.02 |

| Age at Study Enrollment, mean ± SD years | 54.9 ± 11.5 | 52.9 ± 11.4 | 59.3 ± 10.6 | 0.01 |

| Female, no. (%) | 71 (76.3) | 47 (73.4) | 24 (82.8) | 0.33 |

| Race, no. (%) | 0.02 | |||

| White | 79 (84.9) | 57 (89.1) | 22 (75.9) | |

| African American | 8 (8.6) | 2 (3.1) | 6 (20.7) | |

| Asian/Asian American | 3 (3.2) | 3 (4.7) | 0 | |

| Native American /Alaskan Native | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (3.4) | |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 2 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | 0.51 | |||

| Hispanic | 9 (9.7) | 7 (10.9) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 82 (88.2) | 55 (85.9) | 27 (93.1) | |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 2 (3.1) | 0 | |

| SSc Subtype, no. (%) | 0.34 | |||

| Diffuse | 61 (65.6) | 44 (68.8) | 17 (58.6) | |

| Limited | 32 (34.4) | 20 (31.3) | 12 (41.4) | |

| Disease Duration | ||||

| Time from Initial Non-RP Sign/Symptom to Study Enrollment, mean ± SD years | 7.9 ± 7.2 | 7.7 ± 7.6 | 8.5 ± 6.1 | 0.65 |

| Time from Initial Non-RP Sign/Symptom to ILD Diagnosis, mean ± SD years | 4.7 ± 6.4 | 4.6 ± 6.9 | 4.9 ± 5.4 | 0.80 |

| Time from ILD Diagnosis to Study Enrollment, mean ± SD years | 3.2 ± 3.6 | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 3.5 ± 4.3 | 0.65 |

| ILD Duration, mean ± SD years | 4.7 ± 3.6 | 4.6 ± 3.2 | 4.8 ± 4.3 | 0.74 |

| MRSS (At Enrollment) N=89 | 9.4 ± 9.5 | 9.9 ± 9.8 | 8.4 ± 8.9 | 0.51 |

| Autoantibodies, no. (%) | ||||

| ANA Positivity N=86 | 79 (91.9) | 57 (95) | 22 (84.6) | 0.19 |

| ANA Pattern N=76 | 0.10 | |||

| Nucleolar | 11 (14.5) | 9 (16.4) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Centromere | 6 (7.9) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (19) | |

| Other† | 59 (77.6) | 44 (80) | 15 (71.4) | |

| Scl-70 Positivity N=85 | 24 (28.2) | 20 (33.3) | 4 (16) | 0.12 |

| RNA Polymerase III Positivity N=51 | 11 (21.6) | 9 (25.7) | 2 (12.5) | 0.47 |

| PM-Scl Positivity N=35 | 2 (5.7) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (9.1) | 0.54 |

| ILD (HRCT), no. (%) | 0.13 | |||

| NSIP | 84 (90.3) | 60 (93.8) | 24 (82.8) | |

| UIP | 9 (9.7) | 4 (6.3) | 5 (17.2) | |

| PFTs (near ILD Diagnosis) | ||||

| FVC% Predicted, mean ± SD N=93 | 76.2 ± 15.7 | 77.2 ± 14.3 | 73.9 ± 18.5 | 0.35 |

| TLC % Predicted, mean ± SD N=66 | 83 ± 16.3 | 85.0 ± 14.8 | 78.7 ± 18.8 | 0.14 |

| DLco % Predicted, mean ± SD N=85 | 58.3 ± 20.3 | 63.4 ± 20.1 | 46.8 ± 15.6 | <0.001 |

| FVC % Predicted/DLco % Predicted, mean ± SD N=85 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.007 |

| TTE‡ | ||||

| RV Function, no (%) N=92 | <0.001 | |||

| Normal | 84 (91.3) | 62 (98.4) | 22 (75.9) | |

| Abnormal | 8 (8.7) | 1 (3.0) | 7 (24.1) | |

| RV Enlargement, no (%) N=93 | 0.02 | |||

| No | 80 (86.0) | 59 (92.2) | 21 (72.4) | |

| Yes | 13 (14.0) | 5 (7.8) | 8 (27.6) | |

| RVSP (mmHg), mean ± SD N=63* | 37.8 ± 19.6 | 30.9 ± 8.2 | 49 ± 26.7 | <0.001 |

No tricuspid regurgitation jet observed in 30 subjects.

Any positive ANA by IF pattern other than nucleolar or centromere pattern.

TTE data was captured after enrollment in cohort.

SSc-systemic sclerosis; ILD-interstitial lung disease; SSc-ILD-systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease; PH-pulmonary hypertension; RP-Raynaud’s phenomenon; MRSS-modified Rodnan skin score; ANA-antinuclear antibody; IF-immunofluorescence; HRCT-high resolution computed tomography; NSIP-non-specific interstitial pneumonitis; UIP-usual interstitial pneumonitis; PFTs-pulmonary function tests; FVC-forced vital capacity; TLC-total lung capacity; DLco-diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; TTE-echocardiogram; RV-right ventricular; RVSP-right ventricular systolic pressure.

The study duration for subjects within this SSc-ILD cohort was 16.6 (SD ± 4.3) months. At the time of data analysis, twelve subjects were considered as lost to follow up as they had not followed up in clinic for more than 12 months, two subjects had withdrawn consent, and 3 subjects had died. There was a significant trend over time for both FVC and DLCO post-ILD diagnosis in all 93 subjects with SSc-ILD in this cohort. Each year post-ILD diagnosis, FVC was reduced by an average of 1.23% (SE=0.14) and DLCO% was reduced by an average of 1.22 (SE=0.18). However, there was no significant change in FVC or DLCO since study enrollment for all 93 subjects within this SSc-ILD cohort.

Prevalence and Baseline Characteristics of Subjects with SSc-ILD and PH

Twenty-nine subjects (31.2%) in this SSc-ILD cohort had RHC proven PH, which will be defined as the subgroup with “SSc-ILD and PH.” The average time from initial non-RP signs/symptom to PH diagnosis was 7.0 (SD ± 5.5) years, 75.9% (22/29) of subjects with PH had PH diagnosed prior to enrollment in the ILD cohort. Thirty-one percent (9/29) of subjects with SSc-ILD and PH were diagnosed with PH prior to the development of the 2013 recommendations, 65.5% (19/29) subjects with SSc-ILD and PH were diagnosed with PH according to the 2013 recommendations, and one subject with SSc-ILD and PH did not have signs/symptoms for RHC based on 2013 recommendations but underwent RHC due to progressive symptoms and declining DLCO. The remaining 64 subjects with SSc-ILD will be defined as the subgroup “SSc-ILD without PH.” Twenty-four subjects had negative RHC. The remaining 40 subjects did not have signs/symptoms to proceed for an evaluation for RHC based on the 2013 PAH screening recommendations by Khanna et al. (25 subjects); were felt by PH expert to have low likelihood of PH based on available evidence (7 subjects); had a pending RHC at time of data analysis (2 subjects); refused RHC (2 subjects), were lost to cardiology follow up (1 subject), had normalization of previously abnormal TTE findings (2 subjects), or stability of lower DLCO in setting of normal NT-pro BNP and normal TTE (1 subject) (Figure 1). When compared to subjects with SSc-ILD without PH, subjects with SSc-ILD and PH were older at ILD diagnosis (mean age of 55.8 years vs. 49.7 years; p=0.02), had a greater proportion of African American subjects (20.7% vs. 3.1%, p=0.02), and had lower DLCO% predicted (46.8% vs. 63.4%; p<0.001) and FVC% predicted/DLCO % predicted ratio (1.9 vs 1.3; p=0.007) at ILD diagnosis (Table 1).

On analysis of the diagnosis of PH after the initial non-RP sign/symptom, 37.9%, 44.8%, and 48.3% had a diagnosis of PH within 3, 5, and 7 years, respectively. We also performed analyses to evaluate baseline characteristics, cardiopulmonary characteristics, treatments, and outcomes for those with PH diagnosed < 7 years (N=14) compared to ≥ 7 years (N=15) after the initial non-RP sign/symptom, which was based on recent SSc-ILD clinical trial inclusions of disease duration < 7 years from initial non-RP sign/symptom [14, 15]; however, there were no statistically significant differences between those subjects with early diagnosis of PH (< 7 years from initial non-RP) compared to subjects with late diagnosis of PH (≥ 7 years from initial non-RP) except age at initial non-RP sign/symptom [57.2 (SD ± 12.6) vs 45 (SD ± 10.2) years; p=0.008], Scl-70 positivity [0 vs 4 (33.3%); N=25; p= 0.04]; ILD pattern on HRCT [NSIP 14 (100%) vs. NSIP 10 (66.7%) and UIP 5 (33.3%); p= 0.04], and cardiac output (thermodilution) [5.9 (SD 1.8) vs 4.8 (SD 1.1); p= 0.047] (data not shown).

Cardiopulmonary Characteristics of Subjects with SSc-ILD and PH

All CT scans assessed for ILD severity had been obtained a median of 2.2 (IQR 0.3–6.3) months after the diagnosis of PH based on diagnostic RHC.

Seven subjects (24.1%) with SSc-ILD and PH were classified as PAH. Six subjects (20.7%) were classified as WHO Group II PH; three of those subjects had < 20% fibrosis on HRCT and 3 subjects had > 20% fibrosis on HRCT. One of those subjects with WHO Group II PH with > 20% ILD on HRCT also had features of combined post-capillary and pre-capillary PH based on PCWP > 15mmHg and diastolic PAP -PAWP ≥ 7mmHg according to Vachiery et al. and also had features of chronic thromboembolic disease based on pulmonary artery angiogram [16]. Sixteen subjects (55.2%) were classified as WHO Group III PH. Ten subjects (34.5%) with WHO Group III PH had a PVR > 3.0 WU, and four of those subjects (13.8%) were classified as severe PH based on mPAP ≥ 35mmHg [13] (Figure 1). Cardiopulmonary characteristics are summarized for subjects with SSc-ILD and PH in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cardiopulmonary Characteristics of Subjects with SSc-ID and PH

| Cardiopulmonary Characteristics | SSc-ILD and PH (N=29) |

|---|---|

| WHO PH Group, no. (%) | |

| WHO Group 1 | 7 (24.1) |

| WHO Group 2 | 6 (20.7) |

| WHO Group 3 | 16 (55.2) |

| ILD Involvement on HRCT, no. (%) | |

| > 20% | 19 (65.5) |

| < 20% | 10 (34.5) |

| PFTs (at PH Diagnosis), mean ± SD | |

| FVC% Predicted | 70.3 ± 18.1 |

| TLC % predicted | 84.7 ± 16.5 |

| DLco % Predicted | 43.1 ± 15.8 |

| FVC% Predicted / DLco% Predicted | 2 ± 1.5 |

| TTE (at PH Diagnosis), mean ± SD | |

| RVSP (mmHg) N=27* | 44.9 ± 21.6 |

| RAP (mmHg) N=27* | 7.9 ± 3.2 |

| RA Dilation, no. (%) | 13 (44.8) |

| RV Dilation, no. (%) | 11 (37.9) |

| Abnormal RV Function, no. (%) N=28 | 6 (21.4) |

| RHC, mean ± SD | |

| mPAP mmHg | 33.4 ± 7.2 |

| mPCWP mmHg | 13.2 ± 3.2 |

| mRAP mmHg | 9.9 ± 3.3 |

| CO (Fick) | 5.3 ± 1.5 |

| CO (TD) | 5.3 ± 1.5 |

| PVR (WU) | 4.3 ± 3.3 |

| Ranges of mPAP on RHC, no. (%) | |

| mPAP 25 – 35 mmHg | 20 (69) |

| mPAP 35 – 45 mmHg | 8 (27.6) |

| mPAP > 45 mmHg | 1 (3.4) |

| Ranges of PVR on RHC, no (%) | |

| PVR 0 – 6 WU | 21 (72.4) |

| PVR 6 – 12 WU | 7 (24.1) |

| PVR > 12 WU | 1 (3.4) |

No tricuspid regurgitation jet observed in 2 subjects

SSc- systemic sclerosis; ILD- interstitial lung disease; SSc-ILD- systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease; PH- pulmonary hypertension; WHO - World Health Organization; HRCT- high resolution computed tomography; PFTs- pulmonary function tests; FVC- forced vital capacity; TLC- total lung capacity; DLCO- diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; TTE- transthoracic echocardiography; RVSP- right ventricular systolic pressure; RAP –right atrial pressure; RA- right atrial; RV- right ventricular; RHC – right heart catheterization; mPAP – mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PCWP- pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; CO- cardiac output; TD- thermodilution; PVR – pulmonary vascular resistance on RHC; WU- woods units.

We also applied a previously published definition of clinically significant ILD of >30% disease extent on HRCT or if disease extent on HRCT is 10–30%, subjects had an FVC < 70% to have clinically significant ILD to our subjects with PH [17, 18]. Of 29 subjects, 15 (51.7%) had clinically significant ILD.

Treatment and Outcomes of SSc-ILD and PH

Twenty-four subjects (82.8%) with SSc-ILD and PH underwent ILD treatment during their SSc-ILD disease course. Eleven subjects were treated only with mycophenolate mofetil monotherapy, six subjects received mycophenolate mofetil after treatment with cyclophosphamide, two subjects participated in clinical trials and transitioned to mycophenolate mofetil, and other subjects received mycophenolate mofetil and pirfenidone (1 subject), cyclophosphamide followed by rituximab (1 subject), rituximab followed by mycophenolate mofetil and tocilizumab (1 subject), rituximab only (1 subject), and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (1 subject) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment/Outcomes of Subjects with SSc-ILD and PH

| Treatment/Outcome | SSc-ILD and PH (N=29) |

|---|---|

| History of Treatment with PAH Targeted Therapies, no (%) | 24 (82.8) |

| Initial Treatment with PAH Targeted Therapies, no (%) | |

| None | 5 (17.2) |

| PDE5I | 19 (65.5) |

| PDE5I and ERA | 4 (13.8) |

| Intravenous Prostacyclin | 1 (3.4) |

| Most Recent PAH Targeted Therapy Regimen, no (%) | |

| None | 6 (20.7) |

| PDE5I | 13 (44.8) |

| ERA | 1 (3.4) |

| PDE5I and ERA | 3 (10.3) |

| PDE5I and Inhaled Prostacyclin | 1 (3.4) |

| ERA and IV Prostacyclin | 1 (3.4) |

| PDE5I, ERA and Inhaled Prostacyclin | 2 (6.9) |

| PDE5I, ERA, and IV Prostacyclin | 1 (3.4) |

| PDE5I, ERA and Clinical Trial | 1 (3.4) |

| Use of Single Agent PAH Targeted Therapy, no (%) | 11 (37.9) |

| Use of Dual Agent PAH Targeted Therapy, no (%) | 9 (31) |

| Use of Triple Agent PAH Targeted Therapy, no (%) | 4 (13.8) |

| Requirement of Prostacyclin During PH Therapy, no (%) | 6 (20.7) |

| History of ILD Treatment, no (%) | 24 (82.8) |

| History of ILD Treatment with Mycophenolate Mofetil, no (%) | 21 (72.4) |

| History of ILD Treatment with Pulse IV Cyclophosphamide, no (%) | 8 (27.6) |

| Most Recent ILD Treatment, no (%) | |

| None | 9 (31) |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 15 (51.7) |

| Rituximab | 2 (6.9) |

| Tocilizumab and Mycophenolate Mofetil | 1 (3.4) |

| Pirfenidone and Mycophenolate Mofetil | 1 (3.4) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1 (3.4) |

| History of Supplemental Oxygen Use, no (%) | 9 (31) |

| History of Transplant,* no (%) | 1 (3.4) |

| Alive or Deceased, no (%) | |

| Alive | 27 (93.1) |

| Deceased | 2 (6.9) |

| WHO Functional Class (Prior to PH Diagnosis), no (%) | |

| Class I | 0 (0) |

| Class II | 12 (41.4) |

| Class III | 16 (55.2) |

| Class IV | 1 (3.4) |

| WHO Functional Class (Most Recent), no (%) | |

| Class I | 4 (13.8) |

| Class II | 8 (27.6) |

| Class III | 17 (58.6) |

| Class IV | 0 (0) |

Autologous HSCT

SSc – systemic sclerosis; ILD – interstitial lung disease; SSc-ILD – systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease; PH – pulmonary hypertension; PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension; PDE5i – phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor; ERA – endothelin-receptor antagonist; HSCT – hematopoietic stem-cell transplant; WHO – World Health Organization; IV-intravenous.

During their SSc-associated PH (SSc-PH) disease course, 24 subjects (82.8%) with SSc-ILD and PH were treated with PAH specific therapies; 9 subjects (31%) were treated with dual PAH targeted therapy, of which 1 subject was treated with inhaled prostacyclins and another subject was treated with IV prostacyclins, and 4 subjects (13.8%) were treated with triple PAH targeted therapy, of which 2 subjects were treated with inhaled prostacyclins and 2 subjects were treated with IV prostacyclins. Five subjects (17.2%) with SSc-ILD and PH, three of which were characterized as WHO Group II and two of which were characterized as WHO Group III, were not prescribed PAH specific therapies. The majority (79.2%) of subjects treated with PAH specific therapies were started on PDE5i alone and the majority (45.8%) of subjects treated with PAH specific therapies during their SSc-PH disease course were only treated with single agent therapy (Table 3). Out of 24 subjects who were treated with PAH specific therapies, 7 subjects had PAH, 10 subjects had WHO Group III PH with PVR > 3.0 WU, 1 subject had WHO Group II PH with > 20% extent of fibrosis on HRCT and PVR > 3.0 WU, and 1 subject had combined post-capillary and pre-capillary PH; the remaining 5 subjects had WHO Group II or III PH with PVR < 3.0 and were treated with PAH therapy due to unexplained decline in DLCO, worsening symptoms, and/or severe WHO functional class. Twenty subjects (69%) were on ILD therapies and PAH specific therapies simultaneously. Adverse events due to PAH specific therapies used in subjects with SSc-ILD and PH were known side effects for the PAH specific therapies and no case of worsening V/Q mismatch had been observed based on chart review.

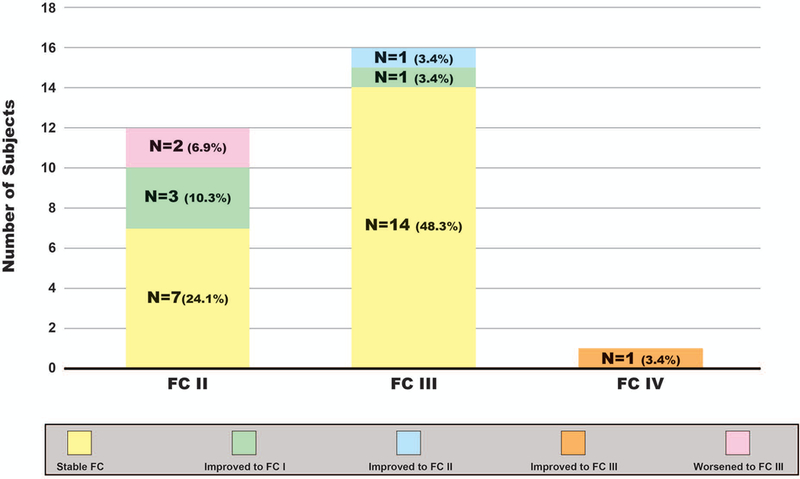

At PH diagnosis and at time of data analysis, most subjects had a WHO functional class of II or III. Five subjects with SSc-ILD and PH, who were on ILD therapies and PAH specific therapies, had improvement in their WHO functional class by at least 1 class from PH diagnosis to time of data analysis; 1 subject with WHO Group III, with hemodynamic features of PAH with PVR > 3.0, who had a PDE5i and ERA added to prior long-term mycophenolate mofetil therapy improved by 2 functional classes from functional class III to I. Sixteen subjects with SSc-ILD and PH on PAH specific therapies, of which four were never treated with ILD therapy, had a stable WHO functional class during their disease course (Figure 2).

Figure 2. SSc-ILD and PH Change in WHO Functional Class.

Histogram depicts FC prior to PH diagnosis for subjects with SSc-ILD and PH (WHO FC II, III, and IV) and the change in FC through time of data analysis. SSc-systemic sclerosis; ILD-interstitial lung disease; SSc-ILD-systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease; PH-pulmonary hypertension; WHO-World Health Organization; FC-functional class

Nine subjects (31%) with SSc-ILD and PH used supplemental oxygen during their PH disease course. No subjects with SSc-ILD and PH underwent heart or lung transplantation during their ILD and/or PH disease course; however, one subject had undergone autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplant 1 year after ILD diagnosis. Two subjects (6.9%) with SSc-ILD and PH died during the study. One subject whose cause of death was due to PH had WHO Group III PH and had been treated with cyclophosphamide followed by mycophenolate mofetil and was not treated with PAH specific therapy. The other deceased subject had PAH and was treated with an ERA and IV prostacyclin and died from a respiratory infection.

Survival Analysis

Overall, 3 subjects in the entire SSc-ILD cohort died (1 from respiratory infection, 1 from pulmonary hypertension, and 1 from an unknown cause due to the patient being lost to follow up). The survival rate at 3 years post SSc-ILD diagnosis for all cohort subjects was 97% (survival standard error = 0.03). Survival analysis for those with SSc-ILD and PH indicated that after diagnosis of PH, 2 subjects died (1 from respiratory infection and the other from PH) resulting in a survival rate at 3 years post PH diagnosis of 91% (survival standard error = 0.06); one of the subjects with SSc-ILD and PH who died had clinically meaningful ILD. For the entire SSc-ILD cohort and those with SSc-ILD and PH, cox proportional hazards regression of time to death was conducted adjusting for current age and race (non-Hispanic white vs. non-white) to account for differences between the cohorts; however, neither of those variables were significant in both survival models.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the prevalence and explored the clinical characteristics, pharmacologic therapies, and outcomes in SSc-ILD. Our results demonstrate that a large proportion of patients with SSc-ILD (31.2%) have co-existing PH, and 37.9% and 48.3% of PH diagnoses occurred within 3 years and 7 years of onset of SSc, respectively. Most subjects with SSc-ILD and PH had WHO group III PH based on > 20% extent of ILD on HRCT (55.2%), and the majority (10/16, 63%) of those subjects with WHO group III PH had hemodynamic features of PAH with PVR > 3.0 WU. Subjects with SSc-ILD and PH were also comprised of a statistically significant proportion of African Americans, which has been referenced in prior SSc studies that have shown African Americans have a higher incidence of PH, and in a recent multicenter African American Cohort, a similar proportion (18%) of subjects had RHC proven PH [19–21]. The majority of subjects who had SSc-ILD and PH had been treated with immunosuppressive therapy for their ILD (82.8%), and 82.8% were treated with PAH therapy. The survival rate for those with SSc-ILD and PH at 3 years after PH diagnosis was 91%, irrespective of ILD and/or PAH specific therapies.

Compared to prior studies that have evaluated SSc subjects with ILD and PH, our cohort is unique as it focused on a cohort of SSc-ILD and assessed prevalence and the clinical course of PH in a prospective fashion, which indicated the co-existence of PH with SSc-ILD is not uncommon. Thus, patients with SSc-ILD may not have cardiopulmonary symptoms solely due to ILD, and may in fact have PH contributing to their abnormal cardiopulmonary symptomatology and physiology. Most studies report PH prevalence only for PAH in subjects without significant lung fibrosis so direct comparison of our results with other study populations is difficult. Also, the high prevalence of PH in our SSc-ILD cohort may reflect some referral bias as our institution is also well known for its PH expertise and our adherence to 2013 recommendations in our population [8]. Our review of original publications identified seven original studies that have discussed RHC-proven SSc-associated PH (SSc-PH) with and without ILD; four studies evaluated SSc-associated PH related to ILD (SSc-PH-ILD), two studies evaluated co-existing ILD in SSc subjects who were initially evaluated for RHC proven PAH, and an additional study by Trad et al. evaluated a cohort of dcSSc subjects, of which 17% had ILD and PAH; although some of those subjects only had TTE proven PAH [17, 18, 22–26]. Thus, future studies need to focus on assessing the prevalence of co-existing PH and ILD in a systematic fashion.

Although the development of PAH is largely thought to be a late complication in SSc, our study indicates a large proportion of patients with SSc-ILD and PH have diagnosis of PH within 5 years of SSc onset [27]. Similar results have been suggested in a study by Mathai et al., which reported a median SSc disease duration of 4 years for all subjects with PH, 3 years for SSc-PH-ILD and 4.5 years for SSc-PAH [23]. Also, in a retrospective multi-center study by Hachulla et al., mean SSc disease duration at PAH diagnosis was 6.3 (SD ± 6.6) years, 55.1% of subjects were classified as early onset PAH based on PAH diagnosis occurring within 5 years of initial non-RP symptom, and over 50% of the population studied had CT evidence of pulmonary fibrosis as well [28]. One possible explanation for the earlier diagnosis of PH being observed may be due to recognition and incorporation of screening algorithms for PH in SSc [6, 8, 12]. This evidence of early development of PH in SSc subjects sheds light on a potential problem that may exist in the current design of SSc-ILD clinical trials, which typically recruit subjects within 5 to 7 years of the initial SSc non-RP sign/symptom and do not require a diagnostic RHC to rule out PH as a cause of cardiopulmonary signs and symptoms.

Clinical trials evaluating PAH therapies typically exclude patients with clinically significant ILD and/or PH due to SSc-PH-ILD; however, according to our experience and other published studies by Launay et al. and Mathai et al., patients with clinically significant ILD and PH are treated with both ILD and PAH therapies [22, 23]. The 5th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension has endorsed the management by expert centers for WHO Group III PH. Their recommendations acknowledge the lack of evidence to use PAH-specific therapies in WHO Group III PH, citing the potential for worsening gas exchange in ILD patients due to ventilation perfusion mismatch. Despite this, our cohort and other cohorts highlight use of PAH-specific therapies in these patients. However, we acknowledge that differentiating WHO Group I PH from WHO Group III PH in this population remains a challenge, and should not be based upon arbitrary cut offs involving FVC and HRCT findings [13]. Patients with SSc-ILD and PH may also have a combination of WHO group I PH and WHO Group III PH, which have different disease mechanisms; PAH is a vasculopathy characterized by vascular remodeling with inflammation, fibrosis, and thrombosis whereas WHO Group III PH is due to vascular destruction from lung fibrosis, vasoconstriction due to chronic hypoxia and/or a vasculopathy similar to that seen in PAH but is “disproportionate” to what is seen in PH due to chronic lung disease [13, 29]. “Out of proportion” PH in some forms of chronic lung diseases has recently been defined by Seeger et al. as severe PH due to chronic lung disease with hemodynamics of mPAP ≥ 35mmHg or mPAP ≥ 25mmHg and a low cardiac index (CI) (< 2.0 L/min/m2) [13]. As evidenced in our cohort, a large proportion of patients with > 20% extent of ILD on HRCT actually have features of both PAH and WHO Group III PH, and individuals within this group were treated with both PAH specific therapies and immunosuppression for ILD on a case-by-case basis. The majority of subjects in our study tolerated PAH specific therapy regardless of simultaneous or prior ILD treatment and had stability in WHO functional class and/or six-minute walk test.

Survival for subjects with coexisting PH in the setting of SSc-ILD has varied across cohorts, but despite the existence of various PAH therapies, survival overall remains poor for both SSc-PAH and SSc-PH-ILD, but tends to be worse if PH is due to ILD. However, our 91% survival rate 3 years after PH diagnosis is higher than survival rates reported in studies by Launay et al., Le Pavec et al, Mathai et al., Michelfelder et al, and Volkmann et al. [17, 18, 22, 23, 25]. Based on our average mPAP and PVR on RHC and use of prostacyclins, our cohort of SSc-ILD and PH appear to have less severe PH than the previously mentioned studies, which is likely due to our aggressive PH screening creating lead time bias and improved survival rates. Our survival rates may also be overestimated due to our small cohort size and infrequent events. We also compared our population of clinically significant ILD (> 30% disease extent on HRCT or if disease extent on HRCT is 10–30%, subjects must have a FVC < 70%) with 51.7% (15/29) of subjects with PH having clinically significant ILD. In comparison, Le Pavec et al. and Volkmann et al. cohorts included SSc subjects with PH and clinically significant ILD with a total of 70 and 71 subjects, respectively, who had 3-year survival estimates of 21% and 50%, respectively [17, 18]. The 3-year survival rate of 91% in our SSc-ILD and PH cohort, of which over 50% of subjects have clinically significant ILD, is likely related to inclusion of HRCT and implementation of 2013 recommendations in all patients seen at the University of Michigan and milder PH based on hemodynamics and use of prostacyclins in our cohort.

Our cohort study also highlights an ongoing dilemma in the classification of SSc-PH as there is lack of a standard definition for what constitutes a significant degree of ILD based on pulmonary physiology and/or radiographic severity to classify subjects as having WHO Group I PH/PAH or WHO Group III PH. Recent data from a single center cohort highlights the lack of specificity of FVC% in the assessment of presence and severity of ILD in SSc [30]. Additional contention regarding the definition of clinically significant ILD is evident when evaluating two recent large clinical trials for PAH targeted therapies; in the PAH trial evaluating combination therapy of ambrisentan and tadalafil and the PAH trial evaluating use of selexipag, patients with moderate to severe restrictive lung disease based on TLC < 60–70% were excluded [31, 32]. Our cohort used a definition for moderate-to-severe ILD to cause WHO Group III PH based on Goh’s criteria with all subjects with features of WHO Group III PH having > 20% extent of ILD on HRCT. Fischer et al., Volkmann et al., and Le Pavec et al. defined SSc-PH-ILD similar to or based on Goh’s criteria; Volkman et al., and Le Pavec et al. specifically used significant ILD as fibrosis extent on HRCT > 30% of lung involvement or if fibrosis extent was 10–30%, FVC had to be < 70% [17, 18, 24]. Launay et al. and Mathai et al. based their SSc-PH-ILD diagnosis on PFTs and HRCT findings [17, 22]. A consensus is urgently needed for the definition of significant ILD to determine whether a patient has SSc-PAH or SSc-PH-ILD.

Our study has many strengths. First, this is a well-characterized prospective SSc-ILD cohort recruited at a single center. Second, all subjects underwent screening for PH with 2013 recommendations by Khanna et al. and those who met criteria underwent a RHC [8].

However, this study is not without limitations. Our results may be skewed as we are a tertiary care center with highly specialized scleroderma, ILD, and PAH clinics. Like other cohorts, the management of PH and ILD was not standardized, which may have impacted the outcomes. Lastly, although we instituted a standardized algorithm screening for PH, we may have missed some patients with mild PH.

CONCLUSION

Patients with SSc-ILD can also develop PH early on in their SSc disease course. These patients with ILD and PH often have dcSSc and often have features of WHO group III due to their ILD but also have hemodynamic features of PAH, which may warrant the use of both immunosuppressive therapies and PAH specific therapies for treatment. The presence of PH early on in SSc-ILD patients is a key factor we must recognize when designing clinical trials for SSc-ILD as PH may be confounding patient-reported outcomes and cardiopulmonary physiology in these patients, which may impact the outcome in clinical trials. Future prospective studies in SSc-ILD should confirm our findings and also explore the impact of the new hemodynamic definition of PH, which was recently proposed at the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension [33, 34].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship:

A. Young is supported by T32-AR007080-38.

D. Khanna is supported by NIH/NIAMS K24 AR063120 and NIH/NIAMS R01 AR-07047.

K. Flaherty is supported by NIH/NHLBI K24 HL111316.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dharshan Vummidi - Consultancies, speaking fees, and honoraria: <$10,000 Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH as member of the Open Source Imaging Consortium. Past royalties from Amirsys for authorship of several chapters in Expert Ddx (relationship ended 4 years ago).

Eric S. White - Consultancies, speaking fees, and honoraria: <$10,000 Boehringer Ingelheim.

Vallerie McLaughlin – Consultant and/or advisor for Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc., Arena, Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Medtronic, Merck, St. Jude Medical, and United Therapeutics Corporation; and the University of Michigan has received research funding from Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc., Arena, Bayer, Gilead, and Sonovie.

Dinesh Khanna - Consultancies, speaking fees, and honoraria: <$10,000 Actelion, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Chemomab, GSK, Medac, Sanofi-Aventis/Genzyme, UCB Pharma; >$10,000 Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Corbus, Cytori, Eicos, EMD Serono, Genentech/Roche. Stock ownership or options: Eicos Sciences, Inc. Employment: University of Michigan and CiviBioPharma, Inc.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent:

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

REFERENCES

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2007;66(7):940–4. 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30933-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Steen VD, Conte C, Owens GR, Medsger TA Jr. Severe restrictive lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37(9):1283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schurawitzki H, Stiglbauer R, Graninger W, Herold C, Polzleitner D, Burghuber OC, et al. Interstitial lung disease in progressive systemic sclerosis: high-resolution CT versus radiography. Radiology 1990;176(3):755–9. 10.1148/radiology.176.3.2389033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinchcliff M, Fischer A, Schiopu E, Steen VD, Investigators P. Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Recognition of Outcomes in Scleroderma (PHAROS): baseline characteristics and description of study population. J Rheumatol 2011;38(10):2172–9. 10.3899/jrheum.101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coghlan JG, Denton CP, Grunig E, Bonderman D, Distler O, Khanna D, et al. Evidence-based detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: the DETECT study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(7):1340–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(11):2737–47. 10.1002/art.38098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna D, Gladue H, Channick R, Chung L, Distler O, Furst DE, et al. Recommendations for screening and detection of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis and rheumatism 2013;65(12):3194–201. 10.1002/art.38172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nihtyanova SI, Schreiber BE, Ong VH, Rosenberg D, Moinzadeh P, Coghlan JG, et al. Prediction of pulmonary complications and long-term survival in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(6):1625–35. 10.1002/art.38390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177(11):1248–54. 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J 2015;46(4):903–75. 10.1183/13993003.01032-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galie N, Simonneau G. The Fifth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(25 Suppl):D1–3. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seeger W, Adir Y, Barbera JA, Champion H, Coghlan JG, Cottin V, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(25 Suppl):D109–16. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354(25):2655–66. 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Khanna D, Kleerup EC, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4(9):708–19. 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vachiery JL, Adir Y, Barbera JA, Champion H, Coghlan JG, Cottin V, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(25 Suppl):D100–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Pavec J, Girgis RE, Lechtzin N, Mathai SC, Launay D, Hummers LK, et al. Systemic sclerosis-related pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease: impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension therapies. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63(8):2456–64. 10.1002/art.30423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volkmann ER, Saggar R, Khanna D, Torres B, Flora A, Yoder L, et al. Improved transplant-free survival in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66(7):1900–8. 10.1002/art.38623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanco I, Mathai S, Shafiq M, Boyce D, Kolb TM, Chami H, et al. Severity of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in African Americans. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93(5):177–85. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reveille JD, Fischbach M, McNearney T, Friedman AW, Aguilar MB, Lisse J, et al. Systemic sclerosis in 3 US ethnic groups: a comparison of clinical, sociodemographic, serologic, and immunogenetic determinants. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism 2001;30(5):332–46. 10.1053/sarh.2001.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan ND, Shah AA, Mayes MD, Domsic RT, Medsger TA Jr., Steen VD, et al. Clinical and serological features of systemic sclerosis in a multicenter African American cohort: Analysis of the genome research in African American scleroderma patients clinical database. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(51):e8980 10.1097/MD.0000000000008980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Launay D, Humbert M, Berezne A, Cottin V, Allanore Y, Couderc LJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival in systemic sclerosis-related pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease. Chest 2011;140(4):1016–24. 10.1378/chest.10-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathai SC, Hummers LK, Champion HC, Wigley FM, Zaiman A, Hassoun PM, et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension associated with the scleroderma spectrum of diseases: impact of interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60(2):569–77. 10.1002/art.24267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer A, Swigris JJ, Bolster MB, Chung L, Csuka ME, Domsic R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease within PHAROS: impact of extent of fibrosis and pulmonary physiology on cardiac haemodynamic parameters. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32(6 Suppl 86): S-109-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michelfelder M, Becker M, Riedlinger A, Siegert E, Dromann D, Yu X, et al. Interstitial lung disease increases mortality in systemic sclerosis patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension without affecting hemodynamics and exercise capacity. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36(2):381–90. 10.1007/s10067-016-3504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trad S, Amoura Z, Beigelman C, Haroche J, Costedoat N, Boutin le TH, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a major mortality factor in diffuse systemic sclerosis, independent of interstitial lung disease. Arthritis and rheumatism 2006;54(1):184–91. 10.1002/art.21538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medsger TA Jr. Natural history of systemic sclerosis and the assessment of disease activity, severity, functional status, and psychologic well-being. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2003;29(2):255–73, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hachulla E, Launay D, Mouthon L, Sitbon O, Berezne A, Guillevin L, et al. Is pulmonary arterial hypertension really a late complication of systemic sclerosis? Chest 2009;136(5):1211–9. 10.1378/chest.08-3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girgis RE, Mathai SC. Pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic respiratory disease. Clin Chest Med 2007;28(1):219–32, 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suliman YA, Dobrota R, Huscher D, Nguyen-Kim TD, Maurer B, Jordan S, et al. Brief Report: Pulmonary Function Tests: High Rate of False-Negative Results in the Early Detection and Screening of Scleroderma-Related Interstitial Lung Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67(12):3256–61. 10.1002/art.39405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, Frey A, Gaine S, Galie N, et al. Selexipag for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015;373(26):2522–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galie N, Barbera JA, Frost AE, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, et al. Initial Use of Ambrisentan plus Tadalafil in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015;373(9):834–44. 10.1056/NEJMoa1413687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frost A, Badesch D, Gibbs JSR, Gopalan D, Khanna D, Manes A, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 53(1). 10.1183/13993003.01904-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 24;53(1). 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.