Abstract

Background & Aims:

Evaluation and treatment of children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) requires serial endoscopic, visual, and histologic assessment by sedated esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Unsedated transnasal endoscopy (TNE) was reported to be successful in a pilot study of children. We evaluated video goggle and virtual reality-based unsedated TNE in children with EoE, collecting data on rates of completion, adverse events, and adequacy of visual and histologic findings.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective study of 190 children and young adults (ages 3–22 years) who underwent video goggle or virtual reality-based unsedated TNE from January 2015 through February 2018. We analyzed data on patient demographics, procedure completion, endoscope type, adverse events, visual and histologic findings, estimated costs, and duration in facility. Esophageal histology reports from the first 173 subjects who underwent TNE were compared with those from previous EGD evaluations.

Results:

During 300 attempts, 294 TNEs were performed (98% rate of success). Fifty-four patients (ages 6–18 years) underwent multiple TNEs for dietary or medical management of EoE. There were no significant adverse events. Visual and histologic findings were adequate for assessment of EoE. TNE reduced costs by 53.4% compared with EGD (TNE $4393.00 vs EGD $9444.33). TNE was used increasingly from 2015 through 2017, comprising 31.8% of endoscopies performed for EoE. Total time in clinic (front desk check-in to check-out) in 2018 was 71 minutes.

Conclusion:

In a retrospective study of 190 children and young adults (ages 3–22 years) who underwent video goggle or virtual reality-based unsedated TNE, TNE was safe and effective and reduced costs of monitoring of EoE. Advantages of TNE include reduced risk and cost associated with anesthesia as well as decreased in-office time, which is of particular relevance for patients with EoE, who require serial EGDs.

Keywords: Eosinophilic Oesophagitis, Anesthesia, Adverse Events, Transnasal Esophagoscopy, Endoscopy, Transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Monitoring of disease in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is primarily done by visual assessment of esophageal mucosa and by histopathological analysis of biopsies obtained during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), and in pediatrics, with sedation or anesthesia.1, 2 Treatment options for EoE include proton pump inhibitors, topical corticosteroids, and dietary therapy. Empiric elimination diets, the 6-food or 4-food elimination diet, require complete removal of foods for 6–8 weeks, followed by endoscopic and histologic assessment to evaluate response. If responsive to the elimination diet, foods are individually re-introduced to identify food triggers in EoE, which could require 6–8 endoscopies over 2 years.

Repeated EGD can be time consuming, place financial burden on families, increase healthcare costs, and have potential risks related to anesthesia.3, 4 These risks are particularly relevant in pediatrics.3 Repeated use of anesthetics has been of increasing concern to parents, particularly with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration “Drug Safety Communication” issued in December 2016 warning that repeated use of anesthetics “may affect the development of children’s brains” (https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532356.htm). In our clinical experience, many parents have other generalized concerns regarding repeated anesthesia to assess disease activity in EoE.

The technique of unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy or more complete transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy, has been developed over the past several years to assess the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum in adults.5, 6 In contrast to traditional EGD, transnasal endoscopy (TNE) collectively offers several distinct advantages. TNE can obtain GI biopsies to evaluate diseases such as EoE or Barrett’s esophagus without sedation during an outpatient visit, as compared to an ambulatory surgery encounter.6–8 Working with pulmonology and otolaryngology, who routinely use bronchoscopes to intubate nasal passages in children, led to the development of unsedated TNE in pediatrics9. Unsedated TNE was performed successfully in a small pilot-cohort of 21 pediatric patients as an alternative to EGD under anesthesia for EoE surveillance9. The aim of this study was to evaluate the ongoing clinical use of pediatric TNE using pediatric bronchoscopes as esophagoscopes to evaluate the completion rate, adverse events (AEs), and adequacy of visual and histologic findings in EoE. We hypothesized that clinic-based TNE would expand in use, have improved in-office implementation, procure adequate biopsy samples, visualize esophageal mucosa, have minimal AEs, and be a lower-cost, well-tolerated, anesthesia-free method to monitor disease activity in EoE.

Methods:

A retrospective study of children who underwent unsedated TNE at a single academic pediatric medical center between January 2015 and February 2018 was performed using data from the program’s clinical database. Subjects referred by their gastroenterologist for TNE were given a web-based video to watch on the process of TNE (http://www.pediatricendoscopy.com) and received a phone call from the endoscopist. Subjects were asked not to eat or drink for 2-hours prior to TNE. In an outpatient clinic room, subjects sat in a chair designed for outpatient laryngoscopy procedures. Staff were pediatric advanced life support certified and rooms had available oxygen, suction, air, and resuscitation equipment.

Subjects wore video goggles for distraction with Sony HMZ-T3W 3-dimensional movie goggles (Tokyo Japan) or Cinemizer Goggles (Oberkocken, Germany), or Samsung Gear Virtual Reality (VR) System (Seoul, South Korea) and chose a video program associated with the goggles. VR system was used starting November 2016 due to technology availability. Parents remained in the room for the TNE. Based on the size of the patient, 4–6 sprays of topical 4% aerosolized lidocaine or single dose aerosolized benzocaine was administered intranasally and orally.

All TNEs were performed by one gastroenterologist (J.F.) and 3 fellows assisted for their training. TNE was performed with a “small” bronchoscope/endoscope, defined as having 2.8–3.1mm outer diameter (OD) with 1.2mm channel (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan, BF XP160 or BF XP190), or a “large” bronchoscope/endoscope, defined as having a 4.0–4.2mm OD (Olympus BF MP160F, BF P190) or 4.9mm OD (Olympus N180). Size was dictated by current model available and by the endoscopist (J.F.) based on a visual exam of the patient’s nasal passage size and tolerance through the nasal passage. The Olympus FB-56D-1 or Boston Scientific Spybite Forceps (Marlborough, Massachusetts) were used in 1.2mm channel and Boston Scientific Radial Jaw 4 Pediatric Biopsy Forceps with Needle were used in 2.0mm channel. Patients were discharged after completion of procedure and asked to maintain clear liquids for 30 minutes.

Demographics, procedural numbers, completion rate, endoscope type, AEs, charges, and duration in facility were collected. AEs were collected both during and after the procedure to characterize post-procedure events. These were classified per reported pediatric grading structure.10 Briefly, grade 1 AEs require phone management, reassurance and supportive care. Grade 2 AEs result in referral to the emergency department or an unanticipated evaluation by a physician. Grade 3 AEs result in admission or significant intervention such as a blood transfusion or repeat endoscopy. Grade 4 AEs result in significant morbidity and mortality, such as unplanned surgery or ICU admission. Grade 5 AEs are defined as death. Serious AEs are defined as grade 2 or above because further medical intervention is recommended or required.10

A review of esophageal biopsy histology of the first 173 subjects who underwent TNE (TNE with 1.2mm channel, n= 61; TNE with 2.0mm channel, n=112) was performed by a pediatric pathologist blinded to which biopsy forceps used (K.C.). Complete presence of the epithelium and lamina propria (LP) were evaluated. The same subjects’ previous EGD under anesthesia was also evaluated for the same features (n= 125). Subjects had 3–4 biopsies taken from both distal esophagus and proximal esophagus. Some subjects also had gastric or duodenal biopsies when requested by the ordering physician. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #16–1796). Statistical analysis of data was performed by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s Post-hoc test. Data is expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, LaJolla, CA) was used to generate figures.

Results:

Demographics and Clinical Utilization of TNE:

During 300 attempts, from January 2015 through February 2018, 294 TNE (98% success rate) were performed on a total of 190 patients, ages 3–22 years. Six subjects were not able to complete TNE due to patient movement before starting. The TNEs were performed in an outpatient clinic room designated for procedures. Demographics and number of endoscopies done with each channel endoscope are shown in Figure 1. TNE was performed in patients ages 3–22 years with mean and median age of 11.5 years and 11 years, respectively. Age ranges were similar using the 1.2mm TNE channel endoscope and 2.0mm TNE channel endoscope.

Figure 1:

Transnasal endoscopies (TNEs) performed from January 2015- February 2018 and demographics.

The total number of TNEs performed increased every year during this period: 48 in 2015, 91 in 2016, 131 in 2017, and by February 2018, 24 in 2018 (Figure 2A)9. This reflects an increasing percent of TNE of total upper endoscopies performed for EoE from 15.7%in 2015 to 31.8% in 2017 (Figure 2B). Time from subject check-in to discharge improved from 2015 to 2018 (Figure 2C). Fifteen subjects were excluded from the time analysis due to an error in the automated time stamp information. Average time from subject check-in until discharge in 2014, during the initial research study, was 89 minutes.9 In 2015, 2016 and 2017, the average time was 72 minutes, 79 minutes, and 79 minutes, respectively (Figure 2C). In 2018, average time was 71 minutes.

Figure 2:

A) Number of transnasal endoscopies (TNE) performed from 2015–2017. B) Number of TNEs performed compared to all diagnostic upper endoscopic procedures. C) Time from patient front desk check-in to patient discharge from office for TNE (minutes) from 2015–2018. D) Average charge per visit for TNE vs Esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

The average charge, adjusted for inflation in 2018, for TNE with biopsy per visit was $4393.00. Estimated charge for sedated EGD with biopsy under general anesthesia in 2018 was $9444.33 (Figure 2D). This does not include pathologist charges. This was a 53.4% reduction in charges for TNE in 2018 compared to EGD.

TNE Use in Disease Management:

Of 294 TNEs performed, 287 or 97.6% were performed for evaluation of EoE. Fifty-four subjects underwent multiple TNE for assessment of changes in treatment for EoE (Figure 3). A total of 159 TNEs were performed on these subjects. The age range for multiple TNE was 6–18 years (Mean 11.2 years, Median 10 years). TNE was performed to assess changes in treatment (Figure 3), with the majority undergoing multiple TNEs to assess after dietary changes (100 TNEs or 62.8%).

Figure 3:

A) Number of subjects who underwent multiple transnasal endoscopies (TNE) and B) Indication for TNE in the management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE).

One subject, who previously did not undergo EGD due to parental concerns related to anesthesia underwent TNE for dysphagia and was diagnosed with EoE. While the majority of patients underwent TNE for EoE, 7 subjects underwent TNE for other indications including dysphagia, follow up for non- EoE esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. One adolescent subject underwent transnasal EGD, including assessment of the duodenum, for evaluation of celiac disease. Additionally, one subject with history of tracheal esophageal fistula/esophageal atresia (TEF/EA) underwent TNE for monitoring of esophagitis.

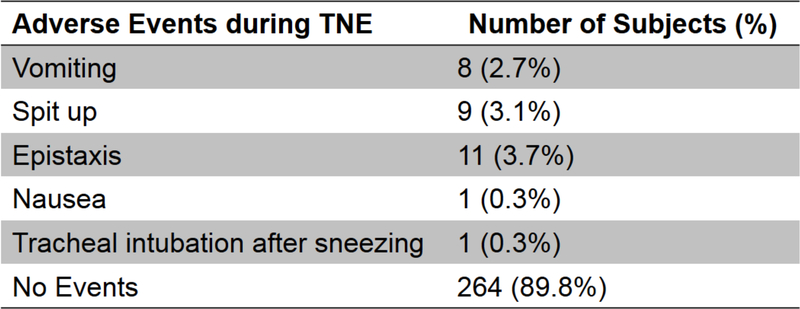

TNE Adverse Events:

All AEs during TNE were grade 1 or lower, requiring no unanticipated medical evaluation or treatment. (Figure 4). Notably, there were no AEs post-procedure. The 3-year-old subject successfully completed TNE but needed to be held during nasal intubation.

Figure 4:

Adverse Events during transnasal endoscopy (TNE).

TNE Findings

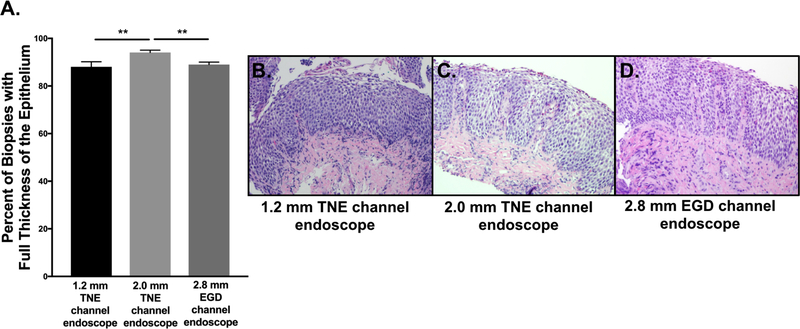

Visual findings of the esophagus are shown in Figure 5. Eighty-eight percent of esophageal biopsies (N=53) obtained with 1.2mm channel TNE endoscope had full thickness of the epithelium while 94% of esophageal biopsies (N=110) obtained with the 2.0mm channel TNE endoscope had full thickness of the epithelium (Figure 6A). Of the available esophageal biopsies from the subject’s previous EGD (2.8mm channel), 89% of esophageal biopsies (N=123) contained full thickness of the epithelium. All biopsy specimens from both endoscope models and forceps were adequate for evaluation defined as including mucosa, with full representation of the epithelial layers from flattened surface epithelium to the basal lamina and submucosa. With TNE, LP was obtained 35% and 40% of the time with the small and large endoscope biopsies, respectively. LP procured in this cohort’s previous EGD was 49%. The evaluation of histological samples also included 18 subjects who had gastric biopsies and 2 subjects that had duodenal biopsies, when requested by the ordering physician, and were also adequate for evaluation.

Figure 5:

A) Visual findings of the esophagus with transnasal endoscopy (TNE). Representative images from TNE including B) normal esophageal mucosa, C) exudate, edema and linear furrows and D) exudate, edema, and linear furrows.

Figure 6:

A) Percent of esophageal biopsies with full thickness of the epithelium obtained by transnasal endoscopy (TNE) with 1.2mm biopsy forceps (2.8–3.1mm TNE), 2.0mm biopsy forceps (4.0–4.9mm TNE), and by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with 2.8mm biopsy forceps. B) Representative images of esophageal biopsies obtained from 1.2mm biopsy forceps, C) 2.0mm biopsy forceps, D) 2.8mm biopsy forceps.

Discussion

Pediatric TNE is a rapidly-expanding, well-tolerated, safe and lower cost clinical tool to monitor disease in EoE in children and young adults that requires no anesthesia. In this study, we showed that TNE is safe as there were no significant AEs. TNE is effective in monitoring disease activity in EoE as it allows for adequate endoscopic visual and histologic assessment of findings in EoE. TNE has become increasingly utilized due to its efficacy, safety, efficiency, and lower cost at our center from the initiation of TNE in 2014 to the time of this publication. We showed that TNE is tolerated in a wide range of children and young adults. Although we performed TNE in a 3-year-old, based on our clinical experience, we would recommend offering it starting at the age of 5 for monitoring of EoE without known esophageal stricture who do not need esophageal dilation. Based on results from a variety of age groups, we provide the following guidance: In children < 5 years old, select children may be able to undergo TNE, therefore we would recommend a detailed discussion. In children ages 5–10, TNE can be performed using the small diameter endoscope. In children >10 years old, TNE can be performed using large diameter endoscope.

One major advantage of TNE is that patients do not require anesthesia for repeated endoscopies in the management of EoE. General anesthesia is more commonly used in pediatric endoscopy, unlike adults who may use conscious IV sedation.4 Repeated use of anesthetics in children has been of increasing concern.3 Several clinical studies are ongoing to better understand these effects in young children.11, 12 This literature, though mostly on children less than 3 years of age, has raised parental awareness and concern surrounding anesthesia for procedures, even in older children3. Additionally, previous pediatric studies have shown risks associated with EGD under general anesthesia and conscious sedation, particularly cardiopulmonary complications in children of all age.4 Pediatric studies evaluating AEs associated with EGD under anesthesia found a total AE rate of 2% and grade 2 or higher AE rate of 1.2%.4, 10 In TNE, there were no AEs grade 2 or higher. Another advantage of TNE is time savings for families, which could also have an effect on adult patients and their providers. Time from check-in to discharge improved over time and in 2018, the average time from check-in to completion of procedure for discharge at 71 minutes. This is shorter than the average 3-hour in hospital time for EGD, not including time needed at home for recovery9.

This is the largest report of in-office, video-goggle and virtual reality based unsedated TNE in pediatrics. It is the first study to use virtual reality goggles as a distraction technique to enable TNE in both children and adults. This technique has the potential to improve the patient experience and expand the use of unsedated TNE in children and adults. The total number of TNEs performed increased every year during this period, encompassing 31.8% of upper endoscopies performed for EoE in 2017. Implementation of TNE over the last 4 years has allowed for a better understanding of utilization and integration into clinical practice. TNE was performed in an outpatient clinic room designated for procedures, not in a day surgery, operating room or procedure center. Because TNE was performed in clinic, it did not hinder anesthesia-based procedures and potentially allowed for expanded procedural opportunity. We showed that TNE is particularly useful in the management of EoE where repeated endoscopies are often necessary for endoscopic and histologic assessment after changes in treatment. The majority of subjects in this study underwent multiple TNEs after the introduction or removal of foods. Dietary therapy is one of the mainstays of treatment in EoE. Studies have shown 75% effectiveness with the 6-food elimination diet.13 Elimination diets require complete removal of these foods for at least 6–8 weeks, followed by endoscopic and histologic assessment with EGD to assess for response to the elimination diet.13, 14 If responsive to the elimination diet, foods are individually reintroduced to identify food triggers in EoE. This could require 6–8 endoscopies over 2 years. In addition, we show that TNE can be used to assess for PPI response. An increasing body of evidence has shown that up to 50% of patients with histologic findings consistent with EoE may respond to PPI therapy and recently published updated consensus recommendations suggest that PPIs may serve as treatment for EoE.15, 16

Alternative methods to measure esophageal inflammation with more favorable risk-benefit profiles compared to EGD under anesthesia could potentially change the practice of long-term surveillance in patients with EoE. While other techniques have been developed to assess mucosal inflammation, including the Cytosponge (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota), esophageal string test (EnteroTrack, Centennial, Colorado), endoluminal functional lumen imaging probe (Crospon, Galway, Ireland) and confocal tethered endomicroscopy, they are currently only available in research settings.17–21 Current guidelines continue to recommend endoscopy with visual and histologic evaluation for monitoring of disease activity.2, 16 TNE, as demonstrated by this study, allows for this assessment with lower cost, greater efficiency, and without the need for anesthesia.

In this study, we found a 53.4% reduction in charges for TNE with biopsy compared to EGD with biopsy. This was mostly due to the lack of anesthesia charges. Patients with EoE have an estimated annual health-care cost of $1.4 billion in the U.S. and that cost is higher in children compared to adults.22 Costs from EoE include off-label medications often not covered by insurance, serial EGDs under anesthesia, food substitutions and elemental formulas that can be more expensive than regular diets.22, 23 TNE allows for cost savings related to decreased anesthesia charges, operating room monitoring and post-anesthesia monitoring, and decreases the overall economic burden to the healthcare system, which will likely continue to rise as the incidence of EoE continues to rise in this chronic disease. Additionally, aside from cost of serial endoscopies under anesthesia, there are direct and indirect costs that are difficult to truly estimate, such as time lost from work and school, and expenses related to travel for the procedure incurred by the caretaker for serial endoscopies under anesthesia.

We show that biopsies from TNE were adequate for epithelial evaluation. Full thickness of the epithelium was obtained 88%, 94%, and 89% of the time using small TNE endoscope, large TNE endoscope, and EGD, respectively. Although there was a statistically significant difference between the groups, the clinical significance of this is difficult to interpret as the biopsies obtained through the 2.0mm channel with TNE had a higher rate of procurement of full epithelium than with EGD. Evaluation of LP has become of increasing interest. In this study, LP yields from TNE were 35% and 40% with endoscopes containing 1.2mm and 2.0mm channel, respectively. LP yield varies significantly, both in pediatric and adult studies, ranging from less than 4% to over 90%.24–26 In this study, procurement of the LP using TNE is consistent with other pediatric literature where 41% and 31% of esophageal biopsies from EGD in patients with and without EoE contained adequate LP, respectively. Adult studies in EoE found LP yields ranging from 55%- 97%, depending on type of biopsy forceps used.26 The type of biopsy forceps may play a role in LP procurement and further studies are needed as LP evaluation becomes increasingly important.26

Although the primary use of TNE in this study was for EoE, it was also used for other indications including evaluation of Barrett’s esophagus, celiac disease, follow-up for esophagitis, and monitoring of pediatric patients with TEF/EA. Recent guidelines for TEF/EA management recommend endoscopy with biopsy for monitoring of GERD in symptomatic patients with TEF/EA.27 Additionally, due to the absence of correlation between symptoms and esophagitis in this high-risk population, guidelines also recommend routine endoscopy 3 times during childhood: after stopping PPI, before the age of 10 years, and at transition to adulthood; therefore, children with TEF/EA may benefit from TNE for this monitoring27. Although Barrett’s esophagus is rare in children, multiple studies document the use of TNE in adults for monitoring of disease, though controversial.7, 8 Further studies evaluating use of TNE for non-EoE pediatric esophageal diseases are needed.

There are limitations to this study. This was a retrospective study performed in a pediatric setting in lower-risk children, who were assessed by their gastroenterologist as capable to undergo TNE to assess EoE. Thus, our findings may not be applicable to all children or adults. This cohort likely represents a highly-motivated group of EoE patients and families that have undergone previous EGD under anesthesia. Pediatric EoE families may have fears around repeated anesthesia events. The lower risk children studied potentially skewed our data towards success and safety, although there are adult studies that document safety in high-risk adults.28 Unsedated TNE has been reported in adults since the 1990’s with high tolerability and efficacy, however, there are is still limited use in pediatric populations and outside Japan and parts of Europe.5, 6, 29, 30 There have been multiple indications reported for unsedated TNE in adults including EoE, reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal varices and first-look GI bleeding.6–8, 30, 31

Conclusion

In summary, video-goggle and virtual reality based unsedated, in-office TNE is safe and effective in monitoring disease activity in EoE in children and young adults ages 3–22 years. Advantages of TNE include decreasing the risk and cost associated with anesthesia and decreasing in-office time, particularly in EoE, where serial EGDs are necessary to monitor disease activity. Mucosal evaluation and histologic sampling obtained from small and large channel endoscopes are adequate to evaluate EoE and potentially other esophageal pathology. Because of its safety profile, further consideration should be given to unsedated TNE in pediatrics, and by extension in adults, to potentially optimize disease monitoring while simultaneously decreasing cost.

What You Need to Know.

Background: Evaluation and treatment of children with eosinophilic esophagitis requires serial endoscopic visual and histologic assessment by sedated esophagogastroduodenoscopy. We evaluated the use of video goggle and virtual reality patient and provider disassociation to enable in-office transnasal endoscopy in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

Findings: Unsedated, video-goggle or virtual reality-assisted, in-office transnasal endoscopy is a safe, effective, cost-saving tool for monitoring the activity of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Mucosal evaluation and biopsies obtained were adequate for evaluation.

Implications for patient care: Inclusion of virtual reality and video goggles could improve patient experience and expand the use of unsedated transnasal endoscopy. Advantages of transnasal endoscopy include reduced risk, cost, and time spent in the office. This is of particular relevance for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, who must undergo serial esophagogastroduodenoscopies for monitoring of disease activity.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Grants from the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2T32DK067009-11 (Nguyen N) and 1K24DK100303 (Furuta GT). The study sponsors played no role in the study design in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Matthew Greenhawt is supported by grant 5K08HS024599-02 from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Manuscript contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Abbreviations:

- (AE)

Adverse Event

- (EoE)

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- (EGD)

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- (GI)

Gastrointestinal

- (LP)

Lamina propria

- (TEF/EA)

Tracheoesophageal Fistula/ Esophageal Atresia

- (TNE)

Transnasal endoscopy

- (VR)

Virtual Reality

Footnotes

Disclosures/ Conflicts of Interest: Joel Friedlander is president, chief medical officer, and co-founder of Triple Endoscopy, Inc. Robin Deterding is Vice President, Consultant, and Co-Founder of Triple Endoscopy, Inc. Emily DeBoer is Secretary, Consultant, and Co-Founder of Triple Endoscopy, Inc. Jeremy Prager is Treasurer, Consultant, and Co-Founder of Triple Endoscopy, Inc. Joel Friedlander, Robin Deterding, Jeremy Prager, and Emily DeBoer are listed inventors on University of Colorado patents pending US 62/732,272, US62/680,798, US 15/853,521, US 15/887,438, CA 2,990,182, AU 2016283112, EU 16815420.1, JP 2017–566710 related to endoscopic methods and technologies. Glenn Furuta is co-founder of EnteroTrack. Matthew Greenhawt has served as a consultant for the Canadian Transportation Agency, Thermo Fisher, Intrommune, and Aimmune Therapeutics; is a member of physician/medical advisory boards for Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, Nutricia, Kaleo Pharmaceutical, Nestle, and Monsanto; is a member of the scientific advisory council for the National Peanut Board; has received honorarium for lectures from Thermo Fisher and Before Brands.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1022–1033 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 2007;133:1342–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ing C, DiMaggio C, Whitehouse A, et al. Long-term differences in language and cognitive function after childhood exposure to anesthesia. Pediatrics 2012;130:e476–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakkar K, El-Serag HB, Mattek N, et al. Complications of pediatric EGD: a 4-year experience in PEDS-CORI. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean R, Dua K, Massey B, et al. A comparative study of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy and conventional EGD. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:422–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, et al. Ultrathin unsedated transnasal gastroscopy in monitoring eosinophilic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:590–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shariff MK, Bird-Lieberman EL, O’Donovan M, et al. Randomized crossover study comparing efficacy of transnasal endoscopy with that of standard endoscopy to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeian K, Staff DM, Vasilopoulos S, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy accurately detects Barrett’s metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:472–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedlander JA, DeBoer EM, Soden JS, et al. Unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy for monitoring therapy in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:299–306 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer RE, Narkewicz MR. Adverse Events Following Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Children: Classifications, Characterizations, and Implications. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;62:828–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner DO, Zaccariello MJ, Katusic SK, et al. Neuropsychological and Behavioral Outcomes after Exposure of Young Children to Procedures Requiring General Anesthesia: The Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) Study. Anesthesiology 2018;129:89–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glatz P, Sandin RH, Pedersen NL, et al. Association of Anesthesia and Surgery During Childhood With Long-term Academic Performance. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:e163470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1097–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Tenias JM, et al. Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Molina-Infante J. Efficacy of Proton Pump Inhibitor Drugs for Inducing Clinical and Histologic Remission in Patients With Symptomatic Esophageal Eosinophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:13–22 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzka DA, Geno DM, Ravi A, et al. Accuracy, safety, and tolerability of tissue collection by Cytosponge vs endoscopy for evaluation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:77–83 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furuta GT, Kagalwalla AF, Lee JJ, et al. The oesophageal string test: a novel, minimally invasive method measures mucosal inflammation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 2013;62:1395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menard-Katcher C, Benitez AJ, Pan Z, et al. Influence of Age and Eosinophilic Esophagitis on Esophageal Distensibility in a Pediatric Cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1466–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo H, Kang D, Katz AJ, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis: a pilot study conducted on biopsy specimens. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2011;140:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen ET, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, et al. Health-care utilization, costs, and the burden of disease related to eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:626–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotton CC, Erim D, Eluri S, et al. Cost Utility Analysis of Topical Steroids Compared With Dietary Elimination for Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:841–849 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta N, Mathur SC, Dumot JA, et al. Adequacy of esophageal squamous mucosa specimens obtained during endoscopy: are standard biopsies sufficient for postablation surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Park JY, Huang R, et al. Obtaining adequate lamina propria for subepithelial fibrosis evaluation in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1207–1214 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bussmann C, Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, et al. Comparison of different biopsy forceps models for tissue sampling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Endoscopy 2016;48:1069–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnan U, Mousa H, Dall’Oglio L, et al. ESPGHAN-NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Esophageal Atresia-Tracheoesophageal Fistula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;63:550–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saeian K, Staff D, Knox J, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy: a new technique for accurately detecting and grading esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2246–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanuma T, Morita Y, Doyama H. Current status of transnasal endoscopy worldwide using ultrathin videoscope for upper gastrointestinal tract. Dig Endosc 2016;28 Suppl 1:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker C, Alexandridis E, Plevris J, et al. Transnasal endoscopy: no gagging no panic! Frontline Gastroenterol 2016;7:246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivory J, Lepilliez V, Gincul R, et al. “First look” unsedated transnasal esogastroduodenoscopy in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding? A prospective evaluation. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2014;38:209–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]