Abstract

Cell division is a highly regulated and carefully orchestrated process. Understanding the mechanisms that promote proper cell division is an important step toward unraveling important questions in cell biology and human health. Early studies seeking to dissect the mechanisms of cell division used classical genetics approaches to identify genes involved in mitosis and deployed biochemical approaches to isolate and identify proteins critical for cell division. These studies underscored that post-translational modifications and cyclin–kinase complexes play roles at the heart of the cell division program. Modern approaches for examining the mechanisms of cell division, including the use of high-throughput methods to study the effects of RNAi, cDNA, and chemical libraries, have evolved to encompass a larger biological and chemical space. Here, we outline some of the classical studies that established a foundation for the field and provide an overview of recent approaches that have advanced the study of cell division.

Keywords: cell cycle, cell division, cancer, chemical biology, computational biology, genomics, proteomics, protein structure, post-translational modification (PTM), classical genetics

Introduction to cell division

Cell division, or mitosis, is the process by which a mother cell divides its nuclear and cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells. Mitosis is divided into four major phases: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Careful regulation of the cell division program is crucial for proper cell growth, development, and gametogenesis. Dysfunction or misregulation of cell division can lead to growth defects (1, 2) and proliferative diseases like cancer (3) and aging-related diseases (4), including Alzheimer's disease (5). Therefore, analyses of the pathways and mechanisms that promote proper cell division are important avenues through which we can understand cell regulation and its misregulation in human disease.

Cell division is driven by two main modes of post-translational modifications. First, protein kinases like cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs)2 (6, 7) and Polo-like kinases (8) phosphorylate their substrates to modify their activity or stability; this modification is opposed by protein phosphatase–mediated dephosphorylation (for example, Cdc25 (9) and various PP2A (10) complexes). Second, E3 ubiquitin ligases like the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) (11) and Cullin 1-based SCF (Skp-Cullin-F box) (12) complexes ubiquitylate their substrates and target them for proteasomal degradation; this modification is opposed by deubiquitylases such as USP37 (13) and Cezanne (14). Spatiotemporal control of when these post-translational modifications occur gives rise to the ordered events of cell division. Our current understanding of key regulators of cell division is founded upon many classical genetic and biochemical studies aimed at understanding the cell cycle. We begin by highlighting some of these seminal studies, transition to discussing modern techniques and approaches used to dissect the mechanisms of cell division, and conclude with future directions and perspectives on the cell division field.

Classical studies of cell division: post-translational regulation

Early cell cycle studies established that phosphorylation was important for cell division. These studies assessed the DNA content, size, and doubling time of mutant strains of the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe to identify genes, termed cell division cycle (cdc) genes (15). One of the first cdc genes to be characterized was cdc9-50, later renamed WEE1 (16). WEE1-mutant yeast divided at a smaller size than their WT counterparts, suggesting that loss of Wee1p activity accelerated mitotic entry and that Wee1p was an inhibitor of mitosis. Later, it was discovered that overexpression of the S. pombe gene cdc25, determined to encode a protein phosphatase (17), led to increased rates of mitotic entry (18). Moreover, Wee1p and Cdc25p worked in opposition to each other, suggesting a balancing act between these two proteins to regulate the initiation of mitosis (19). The cloning of WEE1 indicated that it resembled a protein kinase (20), suggesting that phosphorylation could regulate cell division. This analysis also suggested that a common substrate of Cdc25p and Wee1p was Cdc2p, a protein kinase (21) known to be involved in the initiation of DNA replication (Cdc2p in S. pombe and Cdc28p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, now known as CDK1 in humans) (22). The possibility that Wee1p and Cdc25p worked in opposition to each other at the biochemical level was later confirmed when it was shown that Wee1p phosphorylated and inactivated Cdc2p (23) and that Cdc25p dephosphorylated and activated Cdc2p (17). Thus, the ability of Cdc2p to regulate mitotic entry depended on its phosphorylation state (24), a theme that has now extended to other mitotic kinases.

Meanwhile, parallel studies in frog oocytes demonstrated that a cytoplasmic substance, termed maturation-promoting factor (MPF), regulated the initiation of meiosis (25, 26). Curiously, the levels of MPF seemed to go up and down during the different phases of meiosis (27). Purification of MPF (28) suggested that this protein complex contained two proteins: a protein kinase of ∼32 kDa, later identified to be a homologue of S. pombe Cdc2p (29), and a protein of ∼45 kDa, later identified to be cyclin B (30). The interaction between the kinase Cdc2p and cyclins, a class of proteins named because their protein levels cycled with each mitotic division in sea urchins and clams (31), became a key resource for understanding the mechanisms of cell division. The discovery of CDK2 and CDK2–cyclin A complexes (32, 33) and Cdc2–cyclin A and Cdc2–cyclin B complexes (30, 34) suggested that different cyclin-kinase pairs could regulate different aspects of mitotic entry and progression (32). Subsequent studies in model organisms demonstrated that, among its many substrates, Cdc2 phosphorylated nuclear lamins for nuclear envelope breakdown (35, 36) and cytoskeletal elements for important morphological changes during mitosis (37, 38). The ability of cyclins and their kinases to mediate mitotic entry and progression has become the engine that drives cell division.

Similar to phosphorylation and protein kinases, ubiquitylation and E3 ubiquitin ligases play important roles in cell division (39). For example, the cycling levels of cyclin B were partially explained by the ubiquitination (40, 41) and subsequent degradation of cyclin B by the APC/C (42, 43). Degradation of Emi1 (44) and Wee1 (45) via ubiquitylation of the Cul1-based SCF (Skp-Cullin-F box) complex is necessary for proper mitotic exit. Whereas phosphatases (such as Wee1 or PP2A (10)) have been well studied as antagonizers of cell division kinases, the role of deubiquitinating enzymes and the identification of their substrates remain to be fully explored (46).

Beyond these classical genetic and biochemical studies, modern approaches aimed at dissecting the mechanisms of cell division have greatly advanced our understanding of this dynamic process. Here, we present a broad overview of recent approaches that take a comprehensive and “-omics” view to identify novel components critical for cell division, to understand the function of the cell division machinery, and to analyze the pathways and other novel factors that contribute to cell division.

Genetic dissection of cell division

Although the aforementioned traditional yeast mutagenesis studies were seminal to the field of cell division, in the era of modern genomics, genetic analyses of cell division have become more targeted and efficient. The availability of RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA (47) libraries has made studying gene expression knockdowns a viable option for discovering novel genes involved in cell division (Fig. 1, upper left). Approaches that screen these libraries are usually coupled with a high-throughput method of multiparametric data analysis, such as assessing mitotic progression via microscopy and DNA content or via the HeLa fluorescence ubiquitination cell cycle indicator (FUCCI) cell lines, which change color based on the cell cycle phase (48). As an example, our group performed an siRNA screen to assess the importance of ∼600 mitotic microtubule-associated proteins for their function in cell division and used high content imagers to quantify the mitotic index and apoptotic index of each knockdown (49). Through this approach, we discovered StarD9, a novel protein involved in centrosome cohesion and whose depletion led to a dynamic unstable mitotic arrest (49). Combined with microscopy and computer-aided imaging, siRNA screens have now analyzed the importance of ∼22,000 genes for cell division, uncovering novel proteins critical for this process (50).

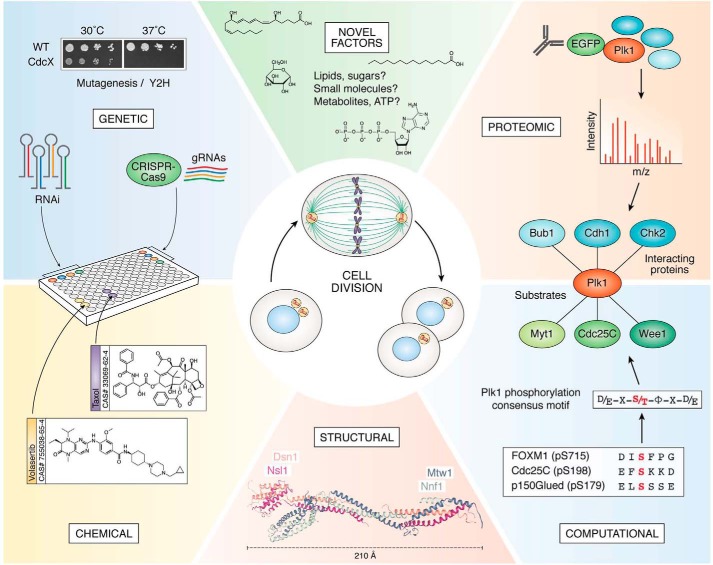

Figure 1.

Overview of approaches used to dissect the mechanisms of cell division. Multiple approaches have been used to dissect the mechanisms of cell division, including genetic, proteomic, chemical, structural, and computational approaches. Figure contains the structure of the MIND complex from Kluyveromyces lactis (84) (Protein Data Bank code 5T58 (127), created using the NGL Viewer (128)). Examples of Plk1-interacting proteins are Bub1 (129), Cdh1 (130), and Chk2 (131). Examples of PLK1 substrates are FOXM1 (8), Cdc25C (132), p150Glued (133), Myt1 (134), and Wee1 (45).

Similarly, expression of fluorescently-tagged fusion proteins, by transfecting vectors encoding cDNAs (51) or bacterial artificial chromosomes containing a gene with its endogenous promoter (52), has enabled the identification of novel cell division proteins. The use of a fluorescently-tagged protein allows for an easy visual analysis for whether the protein has a relevant localization, such as at the kinetochores during mitosis, and is particularly useful when an antibody for the protein of interest is unavailable, either because the protein of interest is novel or because commercially available antibodies could not be validated. Combined with other analyses, such as proteomic data, these approaches have been used to identify novel protein complexes and pathways, such as a subunit of the APC/C (52), the MOZART family of tubulin-associated proteins (52), and the katanin family of microtubule-severing enzymes (53).

Together, these genetic approaches have defined a parts list of the critical factors that are required for proper cell division. Importantly, they have allowed for the dissection of key cell division processes like centrosome homeostasis, early mitotic spindle assembly, spindle assembly checkpoint function, and cytokinesis. These studies have also aided the understanding of human genetic diseases, like developmental disorders and cancers, that have cell division dysregulation at the core of their pathophysiology.

Proteomic dissection of cell division

Classical yeast two-hybrid screens have been used to identify novel protein–protein interactions (54, 55) and to define key domains or amino acids necessary for protein–protein interactions (Fig. 1, upper left) (56). However, modern proteomic approaches have greatly expanded the identification of novel protein–protein interactions and protein complexes involved in cell division. We outline two main approaches to the proteomic mapping of cell division: first, affinity-based purifications, based on the strength of protein–protein interactions; and second, proximity-based purifications, based on the spatiotemporal localization of the protein of interest. In affinity purifications, a tagged protein is expressed within cells, and the protein complexes are immunoprecipitated via antibodies that target the protein tag and are analyzed by MS (Fig. 1, upper right) (51, 57). We have used this approach to study various protein complexes of the cell division machinery, including enzymes that regulate the length of the mitotic spindle (58), ubiquitylation complexes that regulate cytokinesis (59), novel light chains of the dynein machinery (60), and a novel kinesin involved in centrosome cohesion (49, 61, 62). In proximity-based purifications, the protein of interest is tagged with a labeling enzyme such as a BirA biotin-ligase mutant called BioID (135) (or its derivatives BioID2 (136), TurboID, or miniTurboID (63)) or a peroxide-based enzyme APEX (64). Upon addition of the small ligand biotin to the cell culture media, these labeling enzymes modify proximal proteins with biotin via accessible lysine residues. Following the labeling step, the cells are lysed in denaturing conditions, biotinylated proteins are immunoprecipitated by binding to streptavidin beads, and protein complexes are analyzed by MS. Examples of proximity-based approaches include the identification of CDK1 protein interactors (65) and the spatial mapping of protein–protein associations within the centrosome (66).

Our group has been interested not only in defining novel components of the cell division machinery but also how these components interact with each other in a spatiotemporal manner. The mapping of cell division protein–protein interactions has been and will continue to be important for understanding how the cell division machinery coordinates to execute cell division with high fidelity. For example, protein interactors of a mitotic protein kinase could represent components of a protein complex, regulators of its activity or localization, and/or substrates for modification. Therefore, cell division protein–protein interaction networks are critical for defining protein function and more broadly how these proteins affect a specific pathway within the cell division program.

Chemical dissection of cell division

Natural and synthetic small molecules that target the cell division machinery are useful research tools that can be used in an acute and temporal manner to dissect the mechanisms of cell division. They can also serve as lead molecules for the development of therapeutics for treating proliferative diseases like cancer. However, these compounds have shown limited use in clinical trials, emphasizing the need to discover new or improved compounds and/or more viable biological targets. Moreover, many critical regulators of cell division have no specific inhibitors, hindering research to improve our understanding of their function and their potential as disease drug targets. Therefore, much progress needs to be made in the discovery and development of small molecule inhibitors and modulators of cell division proteins.

Recently, we developed a novel cell-based high-throughput chemical screening platform for the discovery of cell cycle phase-specific inhibitors that utilize chemical cell cycle profiling (67, 68). Using this approach we analyzed the cell cycle response of cancer cells to each of ∼80,000 drug-like molecules (Fig. 1, lower left) (67). This screen identified novel inhibitors of each cell cycle phase. Coupled with our computational program CSNAP (Chemical Similarity Network Analysis Pulldown) that relates chemical properties to biological activity (69, 70), this screen presented 266 compounds that impeded cell division and identified many potential biological targets. As an example of the utility of this method, we demonstrated that the novel compound MI-181 was a microtubule destabilizer like colchicine, bound near the colchicine-binding pocket (71), and had a potency and efficacy similar to taxol (67). Recently, we screened more than 180,000 chemical compounds and found a small molecule that arrested leukemia cells in G2 and triggered an apoptotic cell death (72). Similarly, chemical screens have also been used to identify APC/C inhibitors (73) and mitotic kinase inhibitors (for example, Plk1 (74) and Aurora kinases (75)) that have been used to study their corresponding protein's functions in spindle assembly and the spindle-assembly checkpoint (Aurora kinase B (76), Plk1 (77), and APC/C (78)).

Although much work has been done to chemically dissect cell division, much work lies ahead to define inhibitors of the cell division machinery. Importantly, most chemical studies have focused on structure-based approaches, which rely on the prior identification of key cell division enzymes through genetic approaches and an understanding of their 3D structure. High-throughput phenotypic chemical profiling of cell division pathways is still lacking. Additionally, new synthetic and natural chemical libraries with broad chemical space continue to become available and represent opportunities for the discovery of molecules that will enable researchers to interrogate cell division. Finally, much effort has been invested in targeting the active site of mitotic enzymes, but the targeting of key protein–protein interactions with small molecules like peptidomimetics has been lagging.

Structural dissection of cell division

Studies into the structure of key proteins and protein complexes in cell division have elucidated key mechanisms in the assembly and function of the cell division machinery. Although there have been many important structural studies, we focus on Mad2, one of the key regulators of the spindle assembly checkpoint. Structural studies have been particularly useful in elucidating the role of Mad2 within cell division because Mad2 function depends on its structure. Using NMR studies, it was discovered that Mad2 alternates between two main structural conformations, an open (O-Mad2) and a closed (C-Mad2) state, differing mainly at the C-terminal tail (79, 80). Only C-Mad2 is active and able to bind to Mad1 and Cdc20. Conversion of O-Mad2 to C-Mad2 requires the formation of an O-/C-Mad2 heterodimer (81–83). Crystal structures of Mad2–Mad1 complexes demonstrated a flexible C-terminal tail termed the “safety belt” or “hinge loop” (84) involved in regulating C-Mad2 binding to Mad1 (85) and Cdc20 (86) and prohibiting the metaphase–anaphase transition. These structural studies helped elucidate the means by which Mad2 functions within the mitotic checkpoint complex.

Increasing developments in cryo-EM have allowed for more complex structures to be elucidated. For example, cryo-EM studies have solved the structure of the APC/C (87, 88), helping to explain the purpose of both APC/C-binding E2 ubiquitin–conjugating enzymes Ube2c and Ube2s (89) and clarifying the mechanism of Mad2 inhibition of the APC/C (90). Moreover, complex structures like the kinetochores have also been visualized by cryo-EM. Although traditional X-ray crystallography methods have been used to solve the structures of some kinetochore complexes, such as the MIND complex (84) in Fig. 1 (lower middle), cryo-EM structures of yeast kinetochores and kinetochore-associated proteins in situ (91), purified from yeast (92), or reassembled in vitro (93) have elucidated the composition, geometry, and assembly and disassembly of eukaryotic kinetochores. Structural information, particularly of large structures like the kinetochores or centrosomes, is important for understanding the protein complexes formed during mitosis and for developing small molecules that can disrupt these interactions.

Computational dissection of cell division

Computational and mathematical approaches to study cell division have complemented and informed biochemical and biological techniques. One of the earliest attempts toward rationalizing mitotic entry suggested that, because of feedback loops between Cdc2, its activator Cdc25, and its inhibitor Wee1, Cdc2 activity should oscillate within the cell cycle as a function of cyclin concentration (94). These models were later confirmed by experiments that revealed Cdc2 exhibited hysteresis and bistability: regulation of Cdc2 prevents premature mitotic exit because a higher concentration of cyclin B is needed to enter mitosis than to maintain a mitotic state (95, 96). A mathematical model that assessed cell growth as a function of protein kinase activity (97) suggested that an unknown phosphatase might regulate Nek1, a phosphatase later identified to be PP2A–Cdc55 (98). Other mathematical models have taken similar approaches to assess the roles of the spindle assembly checkpoint components relative to checkpoint function (99, 100) and to model the mitotic spindle as a function of biophysical forces (101) and microtubule dynamics and cell size (102).

Computational techniques to glean information from time-lapse imaging of cell division have also been developed. With the advent of advanced imaging software and fluorescently-tagged proteins, researchers have generated spatiotemporal data about protein localization and concentration, resulting in information about protein complex assembly and disassembly (103). Combining datasets from different proteins allowed for the prediction of protein complexes and for the assessment of protein stoichiometry within a complex. Among other results, this imaging technique enabled the quantification of the number of cohesion molecules on DNA during mitosis, confirmed a 1:1 stoichiometry of Aurora kinase B and Borealin, and visualized Aurora kinase B localization to the cytokinetic bridge (103).

Beyond microscopy, computational approaches have also been used to discover novel substrates of mitotic protein kinases. The basic structure of these algorithms is to use sequence information of known phosphorylation sites to identify a consensus phosphorylation motif and predict novel substrates, as outlined in Fig. 1 (lower right) for Plk1. Many computational tools that expand on this basic approach have been published (104, 105); we highlight a recent study that identified SPICE1 as an Aurora kinase A substrate via a computational algorithm and validated the interaction via biochemistry (106).

Given the wealth of information generated by chemical, proteomic, and genetic screens and cheminformatics and bioinformatics analyses, there is a pressing need to develop computational methods to integrate and analyze these data. In regard to this, our group recently used computational cell cycle profiling for prioritizing Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs with the potential for repurposing as anticancer therapies (68). Methods like this that combine and synthesize data sets from multiple sources into multiparametric analyses will become increasingly critical for developing a comprehensive view of cell division and how best to target it for therapeutic purposes.

Future perspectives

Although much has been discovered about the mechanisms that drive cell division, many novel factors that play a role in cell division are still being discovered. For example, endogenous RNA interference (RNAi) has been shown to regulate the expression of cell division proteins like Plk1 (107, 108), Mad1 (109), Bub1 (110), and Aurora kinase B (111). Many other RNAi have been shown to affect at least one aspect of cell division (112–116), and some have no identified targets (117). Given the clinical importance of these RNAi and the therapeutic potential of exogenous RNAi, a systematic understanding of how different forms of RNAi influence the proteins involved in cell division may help uncover novel levels of regulation for cell division.

In addition to RNAi, small molecules and reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to play critical roles in mitotic progression. For example, folate deficiency leads to replicative stress during DNA replication and consequently to mis-segregation defects during mitosis (118). Similarly, the lipid family of phosphoinositides was shown to directly influence mitotic progression through proteins like NuMA (119) or phosphatases (120) and by regulating cytoskeletal elements (121, 122). Sterols have also been shown to play a role in cell division: cells deprived of cholesterol have difficulty undergoing cytokinesis (123), and the cholesterol derivative pregnenolone localizes to the spindle poles, binds Shugoshin 1, and promotes centriole cohesion (124). In S. pombe, intracellular concentrations of glucose affect Wee1 activity and thus cell size at mitotic entry (125). Whether glucose or other metabolites serve roles during mitosis in human cells is largely unexplored. Interestingly, in cancer cells, ROS levels are elevated during mitosis, leading to an increased oxidation of biomolecules, but the functional implications of this oxidation, if any, are unknown (126). Thus, comprehensive metabolomic, lipidomic, and nucleic acid studies of cell division are likely to yield interesting and previously underappreciated biological aspects of cell division (Fig. 1, upper middle).

Concluding remarks

Methods to dissect the mechanisms that govern cell division have progressed rapidly over the last few decades. The strategies discussed here allow for a genome- or proteome-wide assessment of proteins, drugs, and small molecules involved in cell division. In addition, advances in structural biology and computation have aided the study of cell division, particularly with regard to complex structures that are difficult to study with traditional biochemical techniques. Altogether, these approaches have allowed for the discovery and study of the ensemble of proteins and other factors necessary for proper cell division.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Journal of Biological Chemistry for artistic help in constructing Fig. 1.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health NIGMS Grant R01GM117475 (to J. Z. T.), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Institutes of Health NRSA Award GM007185 (UCLA Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Program), and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1650604 (to J. Y. O.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- APC/C

- anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome

- MPF

- maturation-promoting factor

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species.

References

- 1. Tomkins D. J., and Sisken J. E. (1984) Abnormalities in the cell-division cycle in Roberts syndrome fibroblasts: a cellular basis for the phenotypic characteristics? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 36, 1332–1340 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hung C. Y., Volkmar B., Baker J. D., Bauer J. W., Gussoni E., Hainzl S., Klausegger A., Lorenzo J., Mihalek I., Rittinger O., Tekin M., Dallman J. E., and Bodamer O. A. (2017) A defect in the inner kinetochore protein CENPT causes a new syndrome of severe growth failure. PLoS ONE 12, e0189324 10.1371/journal.pone.0189324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanahan D., and Weinberg R. A. (2011) Hallmarks of Cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Macedo J. C., Vaz S., Bakker B., Ribeiro R., Bakker P. L., Escandell J. M., Ferreira M. G., Medema R., Foijer F., and Logarinho E. (2018) FoxM1 repression during human aging leads to mitotic decline and aneuploidy-driven full senescence. Nat. Commun. 9, 2834 10.1038/s41467-018-05258-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang Y., Varvel N. H., Lamb B. T., and Herrup K. (2006) Ectopic cell cycle events link human Alzheimer's disease and amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models. J. Neurosci. 26, 775–784 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3707-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peter M., Nakagawa J., Dorée M., Labbé J. C., and Nigg E. A. (1990) Identification of major nucleolar proteins as candidate mitotic substrates of cdc2 kinase. Cell 60, 791–801 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90093-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bischoff J. R., Friedman P. N., Marshak D. R., Prives C., and Beach D. (1990) Human p53 is phosphorylated by p60-cdc2 and cyclin B-cdc2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 4766–4770 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fu Z., Malureanu L., Huang J., Wang W., Li H., van Deursen J. M., Tindall D. J., and Chen J. (2008) Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of FoxM1 regulates a transcriptional programme required for mitotic progression. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1076–1082 10.1038/ncb1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lammer C., Wagerer S., Saffrich R., Mertens D., Ansorge W., and Hoffmann I. (1998) The cdc25B phosphatase is essential for the G2/M phase transition in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2445–2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Torres J. Z., Ban K. H., and Jackson P. K. (2010) A specific form of phosphoprotein phosphatase 2 regulates anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome association with spindle poles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21, 897–904 10.1091/mbc.e09-07-0598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davey N. E., and Morgan D. O. (2016) Building a regulatory network with short linear sequence motifs: lessons from the Degrons of the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol. Cell 64, 12–23 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu Z. K., Gervais J. L., and Zhang H. (1998) Human CUL-1 associates with the SKP1/SKP2 complex and regulates p21(CIP1/WAF1) and cyclin D proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11324–11329 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang X., Summers M. K., Pham V., Lill J. R., Liu J., Lee G., Kirkpatrick D. S., Jackson P. K., Fang G., and Dixit V. M. (2011) Deubiquitinase USP37 is activated By CDK2 to antagonize APCCDH1 and promote S phase entry. Mol. Cell 42, 511–523 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bonacci T., Suzuki A., Grant G. D., Stanley N., Cook J. G., Brown N. G., and Emanuele M. J. (2018) Cezanne/OTUD7B is a cell cycle-regulated deubiquitinase that antagonizes the degradation of APC/C substrates. EMBO J. 37, e98701 10.15252/embj.201798701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hartwell L. H., Mortimer R. K., Culotti J., and Culotti M. (1973) Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast: V. genetic analysis of cdc mutants. Genetics 74, 267–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nurse P. (1975) Genetic control of cell size at cell division in yeast. Nature 256, 547–551 10.1038/256547a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee M. S., Ogg S., Xu M., Parker L. L., Donoghue D. J., Maller J. L., and Piwnica-Worms H. (1992) cdc25+ encodes a protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates p34cdc2. Mol. Biol. Cell 3, 73–84 10.1091/mbc.3.1.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Russell P., and Nurse P. (1986) cdc25+ functions as an inducer in the mitotic control of fission yeast. Cell 45, 145–153 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90546-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fantes P. (1979) Epistatic gene interactions in the control of division in fission yeast. Nature 279, 428–430 10.1038/279428a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Russell P., and Nurse P. (1987) Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog. Cell 49, 559–567 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hindley J., and Phear G. A. (1984) Sequence of the cell division gene CDC2 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe; patterns of splicing and homology to protein kinases. Gene 31, 129–134 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90203-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conrad M. N., and Newlon C. S. (1983) Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc2 mutants fail to replicate approximately one-third of their nuclear genome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 1000–1012 10.1128/MCB.3.6.1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lundgren K., Walworth N., Booher R., Dembski M., Kirschner M., and Beach D. (1991) mik1 and wee1 cooperate in the inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of cdc2. Cell 64, 1111–1122 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90266-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gould K. L., and Nurse P. (1989) Tyrosine phosphorylation of the fission yeast cdc2+ protein kinase regulates entry into mitosis. Nature 342, 39–45 10.1038/342039a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hara K., Tydeman P., and Kirschner M. (1980) A cytoplasmic clock with the same period as the division cycle in Xenopus eggs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 462–466 10.1073/pnas.77.1.462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Masui Y., and Markert C. L. (1971) Cytoplasmic control of nuclear behavior during meiotic maturation of frog oocytes. J. Exp. Zool. 177, 129–145 10.1002/jez.1401770202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gerhart J., Wu M., and Kirschner M. (1984) Cell cycle dynamics of an M-phase-specific cytoplasmic factor in Xenopus laevis oocytes and eggs. J. Cell Biol. 98, 1247–1255 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lohka M. J., Hayes M. K., and Maller J. L. (1988) Purification of maturation-promoting factor, an intracellular regulator of early mitotic events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3009–3013 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dunphy W. G., Brizuela L., Beach D., and Newport J. (1988) The Xenopus cdc2 protein is a component of MPF, a cytoplasmic regulator of mitosis. Cell 54, 423–431 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90205-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Draetta G., Luca F., Westendorf J., Brizuela L., Ruderman J., and Beach D. (1989) cdc2 protein kinase is complexed with both cyclin A and B: evidence for proteolytic inactivation of MPF. Cell 56, 829–838 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90687-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Evans T., Rosenthal E. T., Youngblom J., Distel D., and Hunt T. (1983) Cyclin: a protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell 33, 389–396 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90420-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pines J., and Hunter T. (1990) Human cyclin A is adenovirus E1A-associated protein p60 and behaves differently from cyclin B. Nature 346, 760–763 10.1038/346760a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsai L.-H., Harlow E., and Meyerson M. (1991) Isolation of the human cdk2 gene that encodes the cyclin A- and adenovirus E1A-associated p33 kinase. Nature 353, 174–177 10.1038/353174a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Labbé J. C., Capony J. P., Caput D., Cavadore J. C., Derancourt J., Kaghad M., Lelias J. M., Picard A., and Dorée M. (1989) MPF from starfish oocytes at first meiotic metaphase is a heterodimer containing one molecule of cdc2 and one molecule of cyclin B. EMBO J. 8, 3053–3058 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08456.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dessev G., Iovcheva-Dessev C., Bischoff J. R., Beach D., and Goldman R. (1991) A complex containing p34cdc2 and cyclin B phosphorylates the nuclear lamin and disassembles nuclei of clam oocytes in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 112, 523–533 10.1083/jcb.112.4.523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peter M., Nakagawa J., Dorée M., Labbé J. C., and Nigg E. A. (1990) In vitro disassembly of the nuclear lamina and M phase-specific phosphorylation of lamins by cdc2 kinase. Cell 61, 591–602 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90471-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chou Y. H., Ngai K. L., and Goldman R. (1991) The regulation of intermediate filament reorganization in mitosis. p34cdc2 phosphorylates vimentin at a unique N-terminal site. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 7325–7328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamashiro S., Yamakita Y., Hosoya H., and Matsumura F. (1991) Phosphorylation of non-muscle caldesmon by p34cdc2 kinase during mitosis. Nature 349, 169–172 10.1038/349169a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ong J. Y., and Torres J. Z. (2019) E3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer and their pharmacological targeting 10.5772/intechopen.82883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hershko A., Ganoth D., Pehrson J., Palazzo R. E., and Cohen L. H. (1991) Methylated ubiquitin inhibits cyclin degradation in clam embryo extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16376–16379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glotzer M., Murray A. W., and Kirschner M. W. (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature 349, 132–138 10.1038/349132a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. King R. W., Peters J. M., Tugendreich S., Rolfe M., Hieter P., and Kirschner M. W. (1995) A 20S complex containing CDC27 and CDC16 catalyzes the mitosis-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to cyclin B. Cell 81, 279–288 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sudakin V., Ganoth D., Dahan A., Heller H., Hershko J., Luca F. C., Ruderman J. V., and Hershko A. (1995) The cyclosome, a large complex containing cyclin-selective ubiquitin ligase activity, targets cyclins for destruction at the end of mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 185–197 10.1091/mbc.6.2.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Margottin-Goguet F., Hsu J. Y., Loktev A., Hsieh H. M., Reimann J. D., and Jackson P. K. (2003) Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF (βTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev. Cell. 4, 813–826 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00153-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watanabe N., Arai H., Nishihara Y., Taniguchi M., Watanabe N., Hunter T., and Osada H. (2004) M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFβ-TrCP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4419–4424 10.1073/pnas.0307700101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mapa C. E., Arsenault H. E., Conti M. M., Poti K. E., and Benanti J. A. (2018) A balance of deubiquitinating enzymes controls cell cycle entry. Mol. Biol. Cell. 29, 2821–2834 10.1091/mbc.E18-07-0425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McKinley K. L., and Cheeseman I. M. (2017) Large-scale analysis of CRISPR/Cas9 cell-cycle knockouts reveals the diversity of p53-dependent responses to cell-cycle defects. Dev. Cell 40, 405–420.e2 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sakaue-Sawano A., Kurokawa H., Morimura T., Hanyu A., Hama H., Osawa H., Kashiwagi S., Fukami K., Miyata T., Miyoshi H., Imamura T., Ogawa M., Masai H., and Miyawaki A. (2008) Visualizing spatiotemporal dynamics of multicellular cell-cycle progression. Cell 132, 487–498 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Torres J. Z., Summers M. K., Peterson D., Brauer M. J., Lee J., Senese S., Gholkar A. A., Lo Y.-C., Lei X., Jung K., Anderson D. C., Davis D. P., Belmont L., and Jackson P. K. (2011) The STARD9/Kif16a kinesin associates with mitotic microtubules and regulates spindle pole assembly. Cell 147, 1309–1323 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neumann B., Walter T., Hériché J.-K., Bulkescher J., Erfle H., Conrad C., Rogers P., Poser I., Held M., Liebel U., Cetin C., Sieckmann F., Pau G., Kabbe R., Wünsche A., et al. (2010) Phenotypic profiling of the human genome by time-lapse microscopy reveals cell division genes. Nature 464, 721–727 10.1038/nature08869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Torres J. Z., Miller J. J., and Jackson P. K. (2009) High-throughput generation of tagged stable cell lines for proteomic analysis. Proteomics 9, 2888–2891 10.1002/pmic.200800873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hutchins J. R., Toyoda Y., Hegemann B., Poser I., Hériché J.-K., Sykora M. M., Augsburg M., Hudecz O., Buschhorn B. A., Bulkescher J., Conrad C., Comartin D., Schleiffer A., Sarov M., Pozniakovsky A., et al. (2010) Systematic analysis of human protein complexes identifies chromosome segregation proteins. Science 328, 593–599 10.1126/science.1181348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheung K., Senese S., Kuang J., Bui N., Ongpipattanakul C., Gholkar A., Cohn W., Capri J., Whitelegge J. P., and Torres J. Z. (2016) Proteomic analysis of the mammalian Katanin family of microtubule-severing enzymes defines Katanin p80 subunit B-like 1 (KATNBL1) as a regulator of mammalian Katanin microtubule-severing. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 15, 1658–1669 10.1074/mcp.M115.056465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jeong A. L., Lee S., Park J. S., Han S., Jang C.-Y., Lim J.-S., Lee M. S., and Yang Y. (2014) Cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (CIP2A) protein is involved in centrosome separation through the regulation of NIMA (never in mitosis gene A)-related kinase 2 (NEK2) protein activity. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 28–40 10.1074/jbc.M113.507954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hwang L. H., Lau L. F., Smith D. L., Mistrot C. A., Hardwick K. G., Hwang E. S., Amon A., and Murray A. W. (1998) Budding yeast Cdc20: a target of the spindle checkpoint. Science 279, 1041–1044 10.1126/science.279.5353.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vidal M., Braun P., Chen E., Boeke J. D., and Harlow E. (1996) Genetic characterization of a mammalian protein–protein interaction domain by using a yeast reverse two-hybrid system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 10321–10326 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bradley M., Ramirez I., Cheung K., Gholkar A. A., and Torres J. Z. (2016) Inducible LAP-tagged stable cell lines for investigating protein function, spatiotemporal localization and protein interaction networks. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 10.3791/54870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xia X., Gholkar A., Senese S., and Torres J. Z. (2015) A LCMT1-PME-1 methylation equilibrium controls mitotic spindle size. Cell Cycle 14, 1938–1947 10.1080/15384101.2015.1026487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gholkar A. A., Senese S., Lo Y.-C., Vides E., Contreras E., Hodara E., Capri J., Whitelegge J. P., and Torres J. Z. (2016) The X-linked-intellectual-disability-associated ubiquitin ligase Mid2 interacts with astrin and regulates astrin levels to promote cell division. Cell Rep. 14, 180–188 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gholkar A. A., Senese S., Lo Y.-C., Capri J., Deardorff W. J., Dharmarajan H., Contreras E., Hodara E., Whitelegge J. P., Jackson P. K., and Torres J. Z. (2015) Tctex1d2 associates with short-rib polydactyly syndrome proteins and is required for ciliogenesis. Cell Cycle 14, 1116–1125 10.4161/15384101.2014.985066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Senese S., Cheung K., Lo Y.-C., Gholkar A. A., Xia X., Wohlschlegel J. A., and Torres J. Z. (2015) A unique insertion in STARD9's motor domain regulates its stability. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 440–452 10.1091/mbc.E14-03-0829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Torres J. Z. (2012) STARD9/Kif16a is a novel mitotic kinesin and antimitotic target. Bioarchitecture 2, 19–22 10.4161/bioa.19766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Branon T. C., Bosch J. A., Sanchez A. D., Udeshi N. D., Svinkina T., Carr S. A., Feldman J. L., Perrimon N., and Ting A. Y. (2018) Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 880–887 10.1038/nbt.4201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rhee H.-W., Zou P., Udeshi N. D., Martell J. D., Mootha V. K., Carr S. A., and Ting A. Y. (2013) Proteomic mapping of mitochondria in living cells via spatially restricted enzymatic tagging. Science 339, 1328–1331 10.1126/science.1230593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schopp I. M., Amaya Ramirez C. C., Debeljak J., Kreibich E., Skribbe M., Wild K., and Béthune J. (2017) Split-BioID a conditional proteomics approach to monitor the composition of spatiotemporally defined protein complexes. Nat. Commun. 8, 15690 10.1038/ncomms15690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Firat-Karalar E. N., Rauniyar N., Yates J. R. 3rd., Stearns T., and Stearns T. (2014) Proximity interactions among centrosome components identify regulators of centriole duplication. Curr. Biol. 24, 664–670 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Senese S., Lo Y. C., Huang D., Zangle T. A., Gholkar A. A., Robert L., Homet B., Ribas A., Summers M. K., Teitell M. A., Damoiseaux R., and Torres J. Z. (2014) Chemical dissection of the cell cycle: probes for cell biology and anti-cancer drug development. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1462 10.1038/cddis.2014.420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lo Y.-C., Senese S., France B., Gholkar A. A., Damoiseaux R., and Torres J. Z. (2017) Computational cell cycle profiling of cancer cells for prioritizing FDA-approved drugs with repurposing potential. Sci. Rep. 7, 11261 10.1038/s41598-017-11508-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lo Y.-C., Senese S., Li C.-M., Hu Q., Huang Y., Damoiseaux R., and Torres J. Z. (2015) Large-scale chemical similarity networks for target profiling of compounds identified in cell-based chemical screens. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004153 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lo Y.-C., Senese S., Damoiseaux R., and Torres J. Z. (2016) 3D chemical similarity networks for structure-based target prediction and scaffold hopping. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 2244–2253 10.1021/acschembio.6b00253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McNamara D. E., Senese S., Yeates T. O., and Torres J. Z. (2015) Structures of potent anticancer compounds bound to tubulin. Protein Sci. 24, 1164–1172 10.1002/pro.2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Xia X., Lo Y.-C., Gholkar A. A., Senese S., Ong J. Y., Velasquez E. F., Damoiseaux R., and Torres J. Z. (2019) Leukemia cell cycle chemical profiling identifies the G2-phase leukemia specific inhibitor leusin-1. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 994–1001 10.1021/acschembio.9b00173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Verma R., Peters N. R., D'Onofrio M., Tochtrop G. P., Sakamoto K. M., Varadan R., Zhang M., Coffino P., Fushman D., Deshaies R. J., and King R. W. (2004) Ubistatins inhibit proteasome-dependent degradation by binding the ubiquitin chain. Science 306, 117–120 10.1126/science.1100946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Steegmaier M., Hoffmann M., Baum A., Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Krssák M., Gürtler U., Garin-Chesa P., Lieb S., Quant J., Grauert M., Adolf G. R., Kraut N., Peters J.-M., and Rettig W. J. (2007) BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr. Biol. 17, 316–322 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ditchfield C., Johnson V. L., Tighe A., Ellston R., Haworth C., Johnson T., Mortlock A., Keen N., and Taylor S. S. (2003) Aurora B couples chromosome alignment with anaphase by targeting BubR1, Mad2, and Cenp-E to kinetochores. J. Cell Biol. 161, 267–280 10.1083/jcb.200208091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gadea B. B., and Ruderman J. V (2005) Aurora kinase inhibitor ZM447439 blocks chromosome-induced spindle assembly, the completion of chromosome condensation, and the establishment of the spindle integrity checkpoint in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1305–18 10.1091/mbc.e04-10-0891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lénárt P., Petronczki M., Steegmaier M., Di Fiore B., Lipp J. J., Hoffmann M., Rettig W. J., Kraut N., and Peters J.-M. (2007) The small-molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of polo-like kinase 1. Curr. Biol. 17, 304–315 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zeng X., Sigoillot F., Gaur S., Choi S., Pfaff K. L., Oh D.-C., Hathaway N., Dimova N., Cuny G. D., and King R. W. (2010) Pharmacologic inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex induces a spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest in the absence of spindle damage. Cancer Cell 18, 382–395 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Luo X., Tang Z., Rizo J., and Yu H. (2002) The Mad2 spindle checkpoint protein undergoes similar major conformational changes upon binding to either Mad1 or Cdc20. Mol. Cell 9, 59–71 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00435-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Luo X., Tang Z., Xia G., Wassmann K., Matsumoto T., Rizo J., and Yu H. (2004) The Mad2 spindle checkpoint protein has two distinct natively folded states. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 338–345 10.1038/nsmb748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hara M., Özkan E., Sun H., Yu H., and Luo X. (2015) Structure of an intermediate conformer of the spindle checkpoint protein Mad2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 11252–11257 10.1073/pnas.1512197112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yang M., Li B., Liu C.-J., Tomchick D. R., Machius M., Rizo J., Yu H., and Luo X. (2008) Insights into Mad2 regulation in the spindle checkpoint revealed by the crystal structure of the symmetric Mad2 dimer. PLoS Biol. 6, e50 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hewitt L., Tighe A., Santaguida S., White A. M., Jones C. D., Musacchio A., Green S., and Taylor S. S. (2010) Sustained Mps1 activity is required in mitosis to recruit O-Mad2 to the Mad1–C-Mad2 core complex. J. Cell Biol. 190, 25–34 10.1083/jcb.201002133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dimitrova Y. N., Jenni S., Valverde R., Khin Y., and Harrison S. C. (2016) Structure of the MIND complex defines a regulatory focus for yeast kinetochore assembly. Cell 167, 1014–1027.e12 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sironi L., Mapelli M., Knapp S., De Antoni A., Jeang K.-T., and Musacchio A. (2002) Crystal structure of the tetrameric Mad1-Mad2 core complex: implications of a “safety belt” binding mechanism for the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 21, 2496–2506 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chao W. C., Kulkarni K., Zhang Z., Kong E. H., and Barford D. (2012) Structure of the mitotic checkpoint complex. Nature 484, 208–213 10.1038/nature10896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chang L. F., Zhang Z., Yang J., McLaughlin S. H., and Barford D. (2014) Molecular architecture and mechanism of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 513, 388–393 10.1038/nature13543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Chang L., Zhang Z., Yang J., McLaughlin S. H., and Barford D. (2015) Atomic structure of the APC/C and its mechanism of protein ubiquitination. Nature 522, 450–454 10.1038/nature14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Brown N. G., VanderLinden R., Watson E. R., Weissmann F., Ordureau A., Wu K.-P., Zhang W., Yu S., Mercredi P. Y., Harrison J. S., Davidson I. F., Qiao R., Lu Y., Dube P., Brunner M. R., et al. (2016) Dual RING E3 architectures regulate multiubiquitination and ubiquitin chain elongation by APC/C. Cell 165, 1440–1453 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Yamaguchi M., VanderLinden R., Weissmann F., Qiao R., Dube P., Brown N. G., Haselbach D., Zhang W., Sidhu S. S., Peters J.-M., Stark H., and Schulman B. A. (2016) Cryo-EM of mitotic checkpoint complex-bound APC/C reveals reciprocal and conformational regulation of ubiquitin ligation. Mol. Cell 63, 593–607 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ng C. T., Deng L., Chen C., Lim H. H., Shi J., Surana U., and Gan L. (2019) Electron cryotomography analysis of Dam1C/DASH at the kinetochore-spindle interface in situ. J. Cell Biol. 218, 455–473 10.1083/jcb.201809088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gonen S., Akiyoshi B., Iadanza M. G., Shi D., Duggan N., Biggins S., and Gonen T. (2012) The structure of purified kinetochores reveals multiple microtubule-attachment sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 925–929 10.1038/nsmb.2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hinshaw S. M., and Harrison S. C. (2019) The structure of the Ctf19c/CCAN from budding yeast. Elife 8, e44239 10.7554/eLife.44239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Novak B., and Tyson J. J. (1993) Numerical analysis of a comprehensive model of M-phase control in Xenopus oocyte extracts and intact embryos. J. Cell Sci. 106, 1153–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pomerening J. R., Sontag E. D., and Ferrell J. E. (2003) Building a cell cycle oscillator: hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 346–351 10.1038/ncb954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sha W., Moore J., Chen K., Lassaletta A. D., Yi C.-S., Tyson J. J., and Sible J. C. (2003) Hysteresis drives cell-cycle transitions in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 975–980 10.1073/pnas.0235349100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Chen K. C., Calzone L., Csikasz-Nagy A., Cross F. R., Novak B., and Tyson J. J. (2004) Integrative analysis of cell cycle control in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3841–3862 10.1091/mbc.e03-11-0794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Queralt E., Lehane C., Novak B., and Uhlmann F. (2006) Downregulation of PP2ACdc55 phosphatase by separase initiates mitotic exit in budding yeast. Cell 125, 719–732 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Henze R., Dittrich P., and Ibrahim B. (2017) A dynamical model for activating and silencing the mitotic checkpoint. Sci. Rep. 7, 3865 10.1038/s41598-017-04218-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mistry H. B., MacCallum D. E., Jackson R. C., Chaplain M. A., and Davidson F. A. (2008) Modeling the temporal evolution of the spindle assembly checkpoint and role of Aurora B kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 20215–20220 10.1073/pnas.0810706106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Civelekoglu-Scholey G., Sharp D. J., Mogilner A., and Scholey J. M. (2006) Model of chromosome motility in Drosophila embryos: adaptation of a general mechanism for rapid mitosis. Biophys. J. 90, 3966–3982 10.1529/biophysj.105.078691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lacroix B., Letort G., Pitayu L., Sallé J., Stefanutti M., Maton G., Ladouceur A.-M., Canman J. C., Maddox P. S., Maddox A. S., Minc N., Nédélec F., and Dumont J. (2018) Microtubule dynamics scale with cell size to set spindle length and assembly timing. Dev. Cell 45, 496–511.e6 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Cai Y., Hossain M. J., Hériché J.-K., Politi A. Z., Walther N., Koch B., Wachsmuth M., Nijmeijer B., Kueblbeck M., Martinic-Kavur M., Ladurner R., Alexander S., Peters J.-M., and Ellenberg J. (2018) Experimental and computational framework for a dynamic protein atlas of human cell division. Nature 561, 411–415 10.1038/s41586-018-0518-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ayati M., Wiredja D., Schlatzer D., Maxwell S., Li M., Koyutürk M., and Chance M. R. (2019) CoPhosK: a method for comprehensive kinase substrate annotation using co-phosphorylation analysis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006678 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Song J., Wang H., Wang J., Leier A., Marquez-Lago T., Yang B., Zhang Z., Akutsu T., Webb G. I., and Daly R. J. (2017) PhosphoPredict: a bioinformatics tool for prediction of human kinase-specific phosphorylation substrates and sites by integrating heterogeneous feature selection. Sci. Rep. 7, 6862 10.1038/s41598-017-07199-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Deretic J., Kerr A., and Welburn J. P. I. (2019) A rapid computational approach identifies SPICE1 as an Aurora kinase substrate. Mol. Biol. Cell. 30, 312–323 10.1091/mbc.E18-08-0495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wang Z.-D., Shen L.-P., Chang C., Zhang X.-Q., Chen Z.-M., Li L., Chen H., and Zhou P.-K. (2016) Long noncoding RNA lnc-RI is a new regulator of mitosis via targeting miRNA-210–3p to release PLK1 mRNA activity. Sci. Rep. 6, 25385 10.1038/srep25385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Shi W., Alajez N. M., Bastianutto C., Hui A. B., Mocanu J. D., Ito E., Busson P., Lo K.-W., Ng R., Waldron J., O'Sullivan B., and Liu F.-F. (2010) Significance of Plk1 regulation by miR-100 in human nasopharyngeal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 126, 2036–2048 10.1002/ijc.24880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Bhattacharjya S., Nath S., Ghose J., Maiti G. P., Biswas N., Bandyopadhyay S., Panda C. K., Bhattacharyya N. P., and Roychoudhury S. (2013) miR-125b promotes cell death by targeting spindle assembly checkpoint gene MAD1 and modulating mitotic progression. Cell Death Differ. 20, 430–442 10.1038/cdd.2012.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Luo M., Weng Y., Tang J., Hu M., Liu Q., Jiang F., Yang D., Liu C., Zhan X., Song P., Bai H., Li B., and Shi Q. (2012) MicroRNA-450a-3p represses cell proliferation and regulates embryo development by regulating Bub1 expression in mouse. PLoS ONE 7, e47914 10.1371/journal.pone.0047914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Mäki-Jouppila J. H., Pruikkonen S., Tambe M. B., Aure M. R., Halonen T., Salmela A.-L., Laine L., Børresen-Dale A.-L., and Kallio M. J. (2015) MicroRNA let-7b regulates genomic balance by targeting Aurora B kinase. Mol. Oncol. 9, 1056–1070 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Hwang W.-L., Jiang J.-K., Yang S.-H., Huang T.-S., Lan H.-Y., Teng H.-W., Yang C.-Y., Tsai Y.-P., Lin C.-H., Wang H.-W., and Yang M.-H. (2014) MicroRNA-146a directs the symmetric division of Snail-dominant colorectal cancer stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 268–280 10.1038/ncb2910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Roy S., Hooiveld G. J., Seehawer M., Caruso S., Heinzmann F., Schneider A. T., Frank A. K., Cardenas D. V., Sonntag R., Luedde M., Trautwein C., Stein I., Pikarsky E., Loosen S., Tacke F., et al. (2018) microRNA 193a-5p regulates levels of nucleolar- and spindle-associated protein 1 to suppress hepatocarcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 155, 1951–1966.e26 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Takacs C. M., and Giraldez A. J. (2016) miR-430 regulates oriented cell division during neural tube development in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 409, 442–450 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Pruikkonen S., and Kallio M. J. (2017) Excess of a Rassf1-targeting microRNA, miR-193a-3p, perturbs cell division fidelity. Br. J. Cancer 116, 1451–1461 10.1038/bjc.2017.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Kriegel A. J., Terhune S. S., Greene A. S., Noon K. R., Pereckas M. S., and Liang M. (2018) Isomer-specific effect of microRNA miR-29b on nuclear morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 14080–14088 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Stein P., Rozhkov N. V., Li F., Cárdenas F. L., Davydenko O., Vandivier L. E., Gregory B. D., Hannon G. J., Schultz R. M., and Schultz R. M. (2015) Essential role for endogenous siRNAs during meiosis in mouse oocytes. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005013 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Bjerregaard V. A., Garribba L., McMurray C. T., Hickson I. D., and Liu Y. (2018) Folate deficiency drives mitotic missegregation of the human FRAXA locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 13003–13008 10.1073/pnas.1808377115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kotak S., Busso C., and Gönczy P. (2014) NuMA interacts with phosphoinositides and links the mitotic spindle with the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 33, 1815–1830 10.15252/embj.201488147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sierra Potchanant E. A., Cerabona D., Sater Z. A., He Y., Sun Z., Gehlhausen J., and Nalepa G. (2017) INPP5E preserves genomic stability through regulation of mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 37, e00500–16 10.1128/MCB.00500-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Zheng P., Baibakov B., Wang X.-H., and Dean J. (2013) PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is constitutively synthesized and required for spindle translocation during meiosis in mouse oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 126, 715–721 10.1242/jcs.118042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Tuncay H., Brinkmann B. F., Steinbacher T., Schürmann A., Gerke V., Iden S., and Ebnet K. (2015) JAM-A regulates cortical dynein localization through Cdc42 to control planar spindle orientation during mitosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 8128 10.1038/ncomms9128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Fernández C., Lobo, Md Mdel V., Gómez-Coronado D., and Lasunción M. A. (2004) Cholesterol is essential for mitosis progression and its deficiency induces polyploid cell formation. Exp. Cell Res. 300, 109–120 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Hamasaki M., Matsumura S., Satou A., Takahashi C., Oda Y., Higashiura C., Ishihama Y., and Toyoshima F. (2014) Pregnenolone functions in centriole cohesion during mitosis. Chem. Biol. 21, 1707–1721 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Allard C. A. H., Opalko H. E., and Moseley J. B. (2019) Stable Pom1 clusters form a glucose-modulated concentration gradient that regulates mitotic entry. Elife 8, e46003 10.7554/eLife.46003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Patterson J. C., Joughin B. A., van de Kooij B., Lim D. C., Lauffenburger D. A., and Yaffe M. B. (2019) ROS and oxidative stress are elevated in mitosis during asynchronous cell cycle progression and are exacerbated by mitotic arrest. Cell Syst. 8, 163–167.e2 10.1016/j.cels.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., and Bourne P. E. (2000) The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 10.1093/nar/28.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Rose A. S., Bradley A. R., Valasatava Y., Duarte J. M., Prlic A., and Rose P. W. (2018) NGL viewer: web-based molecular graphics for large complexes. Bioinformatics 34, 3755–3758 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Jia L., Li B., and Yu H. (2016) The Bub1–Plk1 kinase complex promotes spindle checkpoint signalling through Cdc20 phosphorylation. Nat. Commun. 7, 10818 10.1038/ncomms10818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Bassermann F., Frescas D., Guardavaccaro D., Busino L., Peschiaroli A., and Pagano M. (2008) The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell 134, 256–267 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. van Vugt M. A., Gardino A. K., Linding R., Ostheimer G. J., Reinhardt H. C., Ong S.-E., Tan C. S., Miao H., Keezer S. M., Li J., Pawson T., Lewis T. A., Carr S. A., Smerdon S. J., Brummelkamp T. R., and Yaffe M. B. (2010) A mitotic phosphorylation feedback network connects Cdk1, Plk1, 53BP1, and Chk2 to inactivate the G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoint. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000287 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., and Nishida E. (2002) Plk1 promotes nuclear translocation of human Cdc25C during prophase. EMBO Rep. 3, 341–348 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Li H., Liu X. S., Yang X., Song B., Wang Y., and Liu X. (2010) Polo-like kinase 1 phosphorylation of p150Glued facilitates nuclear envelope breakdown during prophase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14633–14638 10.1073/pnas.1006615107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Nakajima H., Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., and Nishida E. (2003) Identification of a consensus motif for Plk (Polo-like kinase) phosphorylation reveals Myt1 as a Plk1 substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25277–25280 10.1074/jbc.C300126200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Roux K. J., Kim D. I., Raida M., and Burke B. (2012) A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 196, 801–810 10.1083/jcb.201112098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Kim D. I., Jensen S. C., Noble K. A., Kc B., Roux K. H., Motamedchaboki K., and Roux K. J. (2016) An improved smaller biotin ligase for BioID proximity labeling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 27, 1188–1196 10.1091/mbc.E15-12-0844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]