Abstract

In most mammalian species, females regularly interact with kin, which is expected to reduce aggressive competitive behaviour among females. It may thus be difficult to understand why infanticide by females has been reported in numerous species and is sometimes perpetrated by groupmates. Here, we investigate the evolutionary determinants of infanticide by females by combining a quantitative analysis of the taxonomic distribution of infanticide with a qualitative synthesis of the circumstances of infanticidal attacks in published reports. Our results show that female infanticide is widespread across mammals and varies in relation to social organization and life history, being more frequent where females breed in groups and have intense bouts of high reproductive output. Specifically, female infanticide occurs where the proximity of conspecific offspring directly threatens the killer's reproductive success by limiting access to critical resources for her dependent progeny, including food, shelters, care or a social position. By contrast, infanticide is not immediately modulated by the degree of kinship among females, and females occasionally sacrifice closely related infants. Our findings suggest that the potential direct fitness rewards of gaining access to reproductive resources have a stronger influence on the expression of female aggression than the indirect fitness costs of competing against kin.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘The evolution of female-biased kinship in humans and other mammals’.

Keywords: social competition, sexual selection, phylogenetic comparison, sociality, kinship

1. Introduction

Recent work has emphasized that competitive strategies of female mammals are often strikingly symmetrical to those observed in males, including displays and ornaments, fighting and weaponry, dominance hierarchies and reproductive suppression [1–3]. However, while interactions among conspecific male mammals are often contextual and temporally limited to competition over access to mating partners [4,5], interactions among females tend to occur across extended periods and multiple settings [6,7]. Females may thus compete over a diversity of resources—including food, resources necessary to breed (burrows, home-range) or offspring care [8]. In addition, because female mammals are typically philopatric, they may often compete with kin. It has, therefore, proven difficult to identify the determinants of overt female–female competition, in particular in societies that are structured around female kinship. The challenge has been to understand how the direct benefits of competition may be balanced with the indirect fitness costs of competing against kin, especially in the case of extremely harmful behaviour such as infanticide [9,10].

The killing of rivals’ offspring represents one violent manifestation of intrasexual competition, and a significant source of offspring mortality in some populations [11], with adults of both sexes committing infanticide. It has been intensely studied in male mammals, where 50 years of field research have shown that it has evolved as a sexually selected strategy over access to mating partners [12]. In cases where the presence of a dependent offspring prevents the mother from becoming pregnant again, committing an infanticide allows the killer to create extra reproductive opportunities. This strategy is particularly common in polygynous societies where one or a few alpha male(s) monopolize mating opportunities over short periods before losing dominance to others [13–15]. Because in most instances, infanticide is committed by males who recently joined the group, they are unlikely to kill any related offspring [16]. By contrast, as for other forms of female competition, little is known about the determinants and consequences of infanticide by females other than the mother, although it could possibly be more prevalent than infanticide by males, both within and across taxa [17–19]. Unlike males, female killers do not benefit from extra mating opportunities [18,20], because male mammals generally do not invest into offspring care to the extent that it would prevent them from mating with other females [21]. If anything, killing a dependent offspring may exacerbate female mating competition by speeding-up the resumption to fertility for the mother of the victim.

The occurrence of infanticide by females has been more difficult to understand than that by males because mammalian females are often philopatric and therefore frequently encounter kin. As a result, females could be expected to refrain from committing infanticide owing to the risk of indirect fitness costs associated with killing related offspring. However, they might be able to exclusively target unrelated offspring, or the benefits of competition in any or all circumstances might be high enough to outweigh any potential indirect fitness costs. The potential adaptive benefits of female infanticide have been structured around two main hypotheses. The first, suggesting predation for nutritional gains (H1: ‘exploitation’ hypothesis), may not provide a general explanation for female infanticide as killers have relatively rarely been observed to consume victims partially or entirely (e.g. [19,22]), symmetrically to the patterns observed for male infanticide. Instead, killings might facilitate access to resources that are critical to successful reproduction (H2: ‘resource competition’ hypotheses) [18]. Female killers might be defending access to an exclusive territory or shelter, or attempting to expand their breeding space when they target victims outside their home-range (H2.1: ‘breeding space’ hypothesis) (as in black-tailed prairie dogs [23] or Belding's ground squirrels [24]). In species where females only associate temporally to breed, killers may defend access to their own milk, by discouraging attempts to suckle from unrelated infants (H2.2: ‘milk competition’ hypothesis) (as in northern elephant seals: [25]). In species that breed cooperatively, killers may defend access to extra offspring care by group mates other than the mother by altering the helper-to-pup ratio in their own group (H2.3: ‘allocare’ hypothesis) (as in meerkats [9,10], banded mongooses [26,27] or marmoset [28]). Finally, in species that live in stable groups, killers may defend their offspring's future social status (in species with stable hierarchies) or group membership (in species with forcible evictions) by eliminating future rivals (H2.4: ‘social status’ hypothesis) (as in some Old World primates [17,18]).

Here, we present an investigation of the distribution and circumstances of infanticide by female mammals, based on data from 289 species from across 14 different orders collected from the primary literature. The combination of a quantitative synthesis of the taxonomic distribution of infanticide with a qualitative analysis of the circumstances of infanticidal attacks (including traits of the killer and victim) can contribute to reveal the ecological, life history or social determinants of female reproductive competition across mammalian societies, and their relevance to the occurrence of female associations and interactions within and among matrilines. Our aim is to provide a starting point for the investigation of the likely causes and situations under which female infanticide occurs, bearing in mind that our analytical framework suffers from several caveats. First, infanticide is uncommon and difficult to observe, so that some species might wrongly be classified as ‘non-infanticidal’. Second, the analyses rely on a rough categorization of the circumstances of infanticide and may oversimplify its determinants, which could be influenced by multiple factors in a given species. We perform phylogenetic analyses to test the core hypothesis that infanticide in female mammals is predicted by the intensity of resource competition, which might either be mitigated by, or outweigh any potential indirect fitness costs. To do so, we first summarize the social organization and life histories of species in which infanticide by females has been observed, in order to evaluate the conditions under which infanticide is most common (table 1). We predict that the frequent mammalian pattern of female–female kin association will be associated with a reduced risk of infanticide from females, and therefore investigate whether philopatry and higher average relatedness among groups of interacting females reduce the occurrence of female infanticide. Next, we test core predictions generated by each hypothesis for the potential adaptive benefits across species and investigate population-level information on the traits of killers and victims to assess whether females have been observed to commit infanticide when they are most likely to benefit from such killings. All our predictions and tests are summarized in table 2. We first show that, across all species, the distribution and occurrence of infanticide by females is better explained by resource competition than by exploitation. We next test support for each for the four resource-competition hypotheses. We assess whether: (i) instances where females kill offspring in neighbouring ranges (breeding space hypothesis) are most likely explained by competition over breeding space; (ii) instances where females kill offspring born in the same breeding association are most likely explained by competition over milk (milk competition hypothesis); (iii) instances where females kill offspring in groups where usually only a single female reproduces are most likely explained by competition over offspring care (allocare hypothesis); and (iv) instances where females kill offspring born in groups with multiple breeders are most likely explained by competition over social status or group membership (social status hypothesis).

Table 1.

The social and life-history conditions associated with the distribution of infanticide by females. (Females are more likely to commit infanticide in group-living species, but whether breeding females are philopatric or disperse does not appear to be associated with the distribution of infanticide. In general, species with infanticide by females are characterized by high maternal investment, which is either expressed as females having large litters, short lactational and interbirth periods, and/or relatively large offspring.)

| sample of species | all | all | associated breeders | pair breeders | social breeders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| type of infanticide | any |

extraterritorial |

within-group |

within-group |

within-group |

|||||

| infanticide is | absent | present | absent | present | absent | present | absent | present | absent | present |

| sample size | 200 | 89 | 253 | 33 | 34 | 19 | 29 | 16 | 92 | 20 |

| females solitary (% species) | 38% | 16% | 39% | 76% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| female philopatric (% species) | 73% | 68% | 70% | 70% | 65% | 100% | 48% | 31% | 64% | 63% |

| maternal investment (per year relative to bodyweight) | 39% | 118% | 47% | 150% | 48% | 86% | 110% | 169% | 29% | 45% |

| litter size | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| inter-birth interval (days) | 365 | 180 | 340 | 104 | 308 | 212 | 308 | 181 | 453 | 522 |

| age at weaning (days) | 127 | 61 | 113 | 35 | 107 | 59 | 105 | 42 | 229 | 273 |

| offspring weight (relative to bodyweight) | 3.6% | 3.9% | 3.9% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 5.9% | 5.1% | 2.8% | 5.1% | 3.0% |

Table 2.

Testing the core predictions generated by the different hypotheses proposed to explain the distribution of infanticide by females. (For each of the main hypotheses, we tested two core predictions in phylogenetic comparisons and two predictions about the individual traits from the field observations. For the comparisons, we list the sample of species included.)

| hypothesis | type of infanticide/sample of species | core prediction(s) | support? | predictions of individuals' characteristics | support? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: exploitation | any form of infanticide | primarily in carnivores | no | killer: any reproductive state | no |

| across all species | infanticide also by males | no | victim: any age | no | |

| H2: resource competition | any form of infanticide | harsher environments | yes | killer: gestating/lactating | yes |

| across all species | higher maternal investment | yes | victim: dependent on care | yes | |

| H2.1: over breeding space | extraterritorial infanticide | more burrow use | yes | killer: gestating/lactating | yes |

| across all species | exclusive home-ranges | yes | victim: unweaned | yes | |

| H2.2: over milk | within group infanticide | higher energetic milk content | no | killer: lactating | yes |

| across associated breeders | faster offspring growth | no | victim: attempting to nurse | yes | |

| H2.3: over allomaternal care | within group infanticide | allocarers present | yes | killer: gestating/lactating | yes |

| across pair breeders | more helpers/competitors present | yes | victim: dependent on care | yes | |

| H2.4: over social status | within group infanticide | nepotistic hierarchy present | yes | killer: high social rank | yes |

| across social breeders | evictions occur | yes | victim: any age | yes |

2. Material and methods

Following Digby [18], we use a broad definition of infanticide as an act by one or more non-parents that makes a direct or significant contribution to the immediate or imminent death of conspecific young. This definition excludes instances where mothers kill their own offspring (which are considered to result from parent-offspring conflict [29] rather than from intrasexual competition) and includes cases where infants die as the result of the physical aggression (direct infanticide) as well as cases where the enforced neglect of an infant, such as kidnapping, ultimately causes death (indirect infanticide). Although the latter cases are often excluded from studies of infanticide owing to their proximate form of ‘overzealous’ allomaternal care [17], their ultimate consequence—infant death—contributes to shape their evolution as infanticidal behaviour. We included infanticide records from both wild and captive populations for which the killer was unambiguously identified as an adult female. For each species, we recorded whether observations occurred in a captive setting or under natural conditions. Species for which no case of infanticide has ever been observed were included only if detailed observations on individual females and offspring were available, either from repeated captive observations or from field studies occurring across at least three reproductive seasons, to minimize the risk of misclassifying them as ‘non-infanticidal’. Given that infanticide is difficult to observe, we focused on studies that were performed in circumstances under which it could be expressed and detected (co-housing of multiple females; detailed observations of specific females from before birth until weaning) or on studies that followed the fate of one or more offspring cohort(s) and recorded the causes of offspring mortality. Data were collected from searches through the scientific literature, starting with major reviews on the topic of female infanticide [3,4,18,20,30–32] and performing backward and forward citation searches to identify relevant observations. While we might not have included all species in which the status of infanticide by females is documented (i.e. known to be either absent or present), we believe that this search strategy should not lead to systematic biases with regards to the tested hypotheses. We repeated all analyses excluding the 42 species for which we only found observations in captive settings (27 species with and 15 species without female infanticide), which did not change any of the results.

For the comparative analyses, we extracted data for each species on variables linked to the different hypotheses (table 2). From published databases, we obtained information on: social organization (classified as: solitary breeders (breeding females have exclusive ranges in which they do not tolerate any other breeding individual), pair breeders (home-ranges contain a single breeding female and a single breeding male but may contain additional non-breeding individuals), associated breeders (females share the same space for breeding but associations are unstable and tend not to last beyond the breeding season), or social breeders (several breeding females share the same home-range across multiple breeding seasons)) [33]; female philopatry and dispersal (whether most breeding females have been born in their current locality/group or elsewhere) [34]; carnivory (whether the diet of a species includes meat or not) [35]; infanticide by males (whether males have been observed to kill conspecific young) [14]; environmental climatic harshness (a principal component derived by the authors of the original publication, with high values indicating that rainfall is low and temperatures are cold and unpredictable across the known range of a species) [36]; maternal investment (mean body size of offspring at weaning multiplied by the mean number of offspring per year, divided by mean body mass of adult females) [37]; the use of burrows or nest holes for breeding (information was taken from the papers used to extract information on the absence or presence of infanticide by females); litter size (number of offspring per birth); offspring mass at birth (grams); weaning age (age at which offspring are independent, in days); inter-birth interval (time between consecutive births, in days) [38]; energetic value of milk (MJ ml−1 based on the protein, sugar and fat composition) [39–41]; and offspring care by fathers and/or non-parental group members (whether offspring receive milk or food from or are being regularly carried by group members who are not the mother) [33]. In addition, we completed information obtained from these databases by collecting extra data from the primary literature on dominance hierarchies and mechanisms of rank acquisition in social groups (whether all adult females can be arranged in a dominance hierarchy and if so, whether an individual's rank is influenced by age and/or nepotism); and forcible evictions (whether females use aggression to exclude other females from their own social group). For each species in which females had been observed to kill conspecific young, we used the primary literature to record as much information as possible regarding the characteristics of the killer (age and reproductive state) and of the victim (age, sex and relatedness to killer) to test specific predictions. The full dataset is provided in the electronic supplementary material, tables S1 (comparative data) and S2 (individual characteristics data), with all references for data specifically collected here in the electronic supplementary material, File S1.

In addition to performing comparisons assessing contrasts in the presence or absence of infanticide across all species in our sample, we classified species into different types according to each of the four resource competition hypotheses (table 2). This classification also aimed at controlling for a potential confounding effect of social organization, as our analysis might otherwise detect factors associated with the evolution of sociality if females are more likely to have been observed to commit infanticide in some social systems. For the breeding space hypothesis, we only included instances of infanticide in which females did not share a home-range with the mother of the victims; for the milk competition hypothesis, we restricted the sample to associated breeders; for the allocare hypothesis, we only included pairs; and for the social competition hypothesis, we only looked at social breeders.

For the comparative analyses, the phylogenetic relatedness between species was inferred from the updated mammalian supertree [42]. We fitted separate phylogenetic models using MCMCglmm [43] to identify the extent to which each of the predicted variables (table 2) explains the presence of infanticide by females across species (binary response, assuming a categorical family of trait distribution). Following the recommendations of Hadfield [44], we set the priors using an uninformative distribution (with variance, V, set to 0.5 and belief parameter, nu, set to 0.002). Each model was run three times for 100 000 iterations with a burn-in of 20 000, visually checked for convergence and for agreement between separate runs.

3. Results

(a). Social organization and infanticide by females

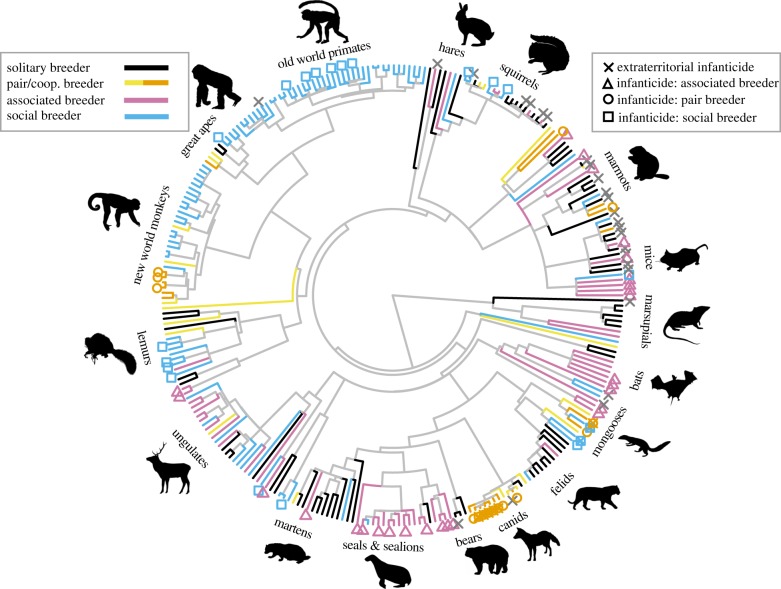

Infanticide by females has been observed in 89 (31%) of the 289 mammalian species in our sample (table 1). Female infanticide (of any type) varies with the social organization and is more frequent when females breed in groups (figure 1): it has been observed in 43% of associated breeders, in 36% of pair breeders and in 30% of social breeders, but only in 18% of solitary breeders. Across all species, females are equally likely to kill offspring when they are philopatric (47 of 135 species, 34%) than when they disperse to breed (17 of 59 species, 29%) (effect of female dispersal on the presence of infanticide by females: −10.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) −39.3–11.3, p = 0.34) but there are differences for two types of social organization: across associated breeders infanticide only occurs in philopatric species; while across pair breeders infanticide is more likely to occur in species in which females disperse (table 1). Across all group-living species (associated breeders, pair breeders with helpers, social breeders), there is no relationship between levels of average relatedness among female group members and whether infanticide by females of offspring born in the same group does (median levels of average relatedness across 10 species 0.09, range 0.01–0.38) or does not occur (median levels of average relatedness across 24 species 0.21, range −0.03–0.52) (effect of levels of average relatedness on the presence of infanticide by females: −21.1, 95% CI −81.4–10.1, p = 0.18). Across species in which groups are stable (i.e. excluding associated breeders where groups are sometimes difficult to define and can be very large), levels of average relatedness are slightly higher when infanticide occurs (see also [45]). The population-level information show instances of killers being close kin of the victim in 33% of species (22 of 65), with either grandmothers killing their grandchildren or aunts killing their nieces, with kin being common victims in cooperative breeders (8 of 12 cooperative breeders) but also in several social breeders (14 of 51 social breeders).

Figure 1.

The distribution of the different forms of infanticide by females in relation to the social organization across the mammalian species in our sample (pictures are from phylopic.org, for full credit see the electronic supplementary material, File S2).

(b). Life histories and infanticide by females

Energetic investment into reproduction by mothers is higher in species with any form of infanticide by females compared to the remaining species (table 1). However, these patterns do not reflect a uniform association between infanticide and all of the energetic investment variables, but rather that infanticide is associated with specific measures of investment in each breeding system. Among species with a single breeding female per home range (extraterritorial infanticide and infanticide in pair breeders), infanticide occurs in those with larger litters (table 1). Species in which females kill offspring in a breeding association are characterized by fast-growing offspring, while offspring are relatively small at birth in species in which females kill offspring in stable groups (table 1).

(i). H1: Exploitation

We find no support for predictions suggesting that females kill conspecific offspring primarily for exploitation (table 2). Across species, infanticide by females is as likely to occur in the absence of infanticide by males (44 of 147 species, 30%) as in its presence (43 of 135 species, 32%) (effect of the presence of male infanticide on the presence of female infanticide 2.1, 95% CI −13.5–16.9, p = 0.74). Similarly, carnivorous species are not more likely to show infanticide by females (18 of 56 species, 32%) than species in which meat does not constitute an important part of the diet (59 of 192 species, 31%) (effect of carnivory on the presence of female infanticide −0.7, 95% CI −11.2–10.0, p = 0.89). The age of victims varies from birth to beyond independence across species, but is more homogeneous within each type of infanticide (see below), so that killings do not appear simply opportunistic.

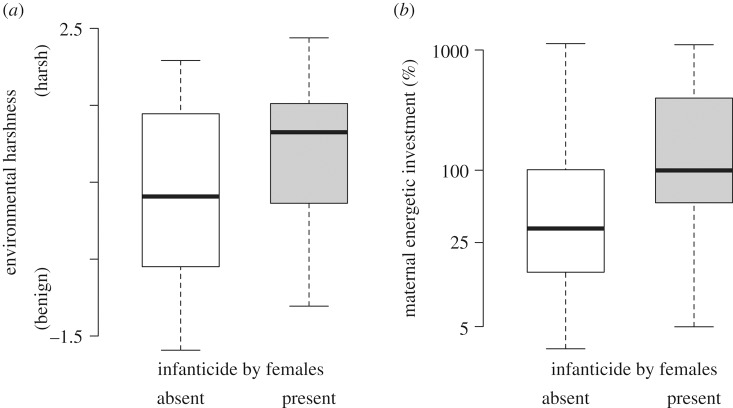

(ii). H2: Resource competition

Infanticide by females appears more likely to occur where competition over resources is expected to be more intense (table 2). The climatic environments of species in which females commit infanticide are harsher (as estimated by a principal component reflecting the exposure to drier environments with colder and less predictable annual temperatures) than the environments of species in which infanticide has not been observed (effect of environmental harshness on the presence of female infanticide 7.0, 95% CI −0.2–14.7, p = 0.03, 54 species with infanticide and 193 without) (figure 2a). In species where females commit infanticide, they invest substantially more energy into the production of offspring, being able to produce the equivalent of 1.0 times their own body mass in offspring mass per year (number of offspring times mass of weaned offspring; median across 41 species, range 0.05–12.1 times) compared to 0.33 times in species in which infanticide has not been observed (median across 77 species, range 0.03–11.1) (effect of maternal energetic investment on the presence of female infanticide 25.8, 95% CI 1.5–58.7, p < 0.001) (figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Factors associated with female competition and the distribution of infanticide by females. Species in which female infanticide is present are, on average, characterized by (a) living in harsher environments (lower and more unpredictable rainfall and temperatures) and by (b) higher maternal energetic investment (total mass of weaned offspring produced per year relative to maternal mass). Black lines indicate the median across the species in the sample, boxes contain 75% of the values, and whiskers extend to the extremes.

(iii). H2.1: Competition over breeding space

Thirty-two of the 33 species in which females kill offspring outside their own home-range keep their offspring in burrows or holes, compared to 93 of the 163 species in which infanticide by females appears absent (effect of burrow use on the presence of infanticide by females 14.4, 95% CI 6.0–22.9, p < 0.001). The exception is Semnopithecus entellus, where ‘females occasionally steal infants from a neighbouring troop’ [17,46]. In most species in which females kill offspring in neighbouring home-ranges (25 of 33), females generally appear not to tolerate other breeding females close by and most home-ranges only contain a single breeding female (solitary or cooperatively breeding species), while in most other species females form associations or groups (home-ranges contain a single breeding female in 105 of 268 species) (effect of the presence of a single breeding female per home-range on the presence of infanticide by females 12.4, 95% CI 0.3–30.1, p = 0.007). In all cases, the killer was either pregnant or had dependent young of her own (17 species with observations), and all offspring that were killed were not yet weaned (17 species).

(iv). H2.2: Competition over milk

Among associated breeders, those species with infanticide are not characterized by higher milk energy content (2.8 MJ 100 ml−1, median across eight species, range 1.2–4.7) than those in which killings have not been observed (2.1 MJ 100 ml−1, median across seven species, range 0.8–5.7) (mean effect of milk energy on the presence of infanticide by females 2.0, 95% CI −66.3–83.1, p = 0.97). In associated breeders with female infanticide, offspring do not seem to have greater growth rates (they gain on average 0.28% of their adult body mass per day until weaning, median across nine species, range 0.04–1.72%) than in species in which females have not been observed to kill offspring (offspring gain on average 0.17% of their adult body mass per day until weaning, median across 11 species, range 0.05–0.73%) (effect of the presence of infanticide by females on offspring growth rate 6.1, 95% CI −16.2–35.4, p = 0.59). Killers are either pregnant or have dependent young (21 of 21 species) and are not primiparous. All victims were reported to be unweaned (22 of 22 species). In 7 of 14 infanticide reports from associated breeders, victims were killed as they attempted to suckle from the killer.

(v). H2.3 Competition over allomaternal care

Infanticide by females in pair breeders occurs only when fathers provide care (all 16 species) while fathers care for offspring in only 16 of the 39 pair breeding species in which this form of infanticide is absent. In 15 of the 16 pair breeders with female infanticide, additional helpers are present (cooperative breeders), while there are only a further seven cooperatively breeding species in which females have not been observed to kill offspring from their own group (female infanticide occurs in 68% (15 of 22) of cooperative breeders versus in 4% (1 of 23) of pair breeders in which there are no other helpers). Across species in which offspring receive allocare, the number of potential allocarers is higher in species with, compared to species without female infanticide (infanticide present: three allocarers per group, median across 15 species, range 2–23; infanticide absent: two allocarers per group, median across 13 species, range 1–20; effect of number of allocarers on the presence of infanticide 25.3, 95% CI 1.9–48.6, p = 0.02). The killer was usually the dominant breeder (as was regularly the case in 9 of 12 species) and was pregnant or with dependent infants in all cases. In most instances the killer and the victim belonged to the same group (11 of 14 species) and were consequently related (10 out of 13 species). Victims were often a few days old and all were dependent.

(vi). H2.4: Competition over social status

Of the 27 social breeders with female philopatry (and available data), female group members do not form social hierarchies in three species, hierarchical rank is determined by age in five species, and rank is influenced by nepotism in 19 species. Females have been observed to kill offspring born to other group members in eight of these latter 19 species, but in none of the species where nepotism does not influence female rank (effect of presence of nepotistic rank acquisition on the presence of infanticide by females 134.1, 95% CI 28.8–238.1, p < 0.001). Females are more likely to kill offspring born to other females in social breeders in which they also aggressively evict other females from their group (infanticide has been observed in 6 of 10 species with evictions and 7 of 35 without evictions) (effect of occurrence of evictions on the presence of infanticide by females 7.8, 95% CI −0.2–14.4, p = 0.02). In all 12 social breeders in which infanticide events have been observed, killers were old and high-ranking. Killers were never pregnant, but in all cases had dependent young of their own. Victims were not yet weaned, and victims might be related to the killer in 5 of 12 species. There is only one species where the data suggest that females might preferentially kill offspring of one sex: in Macaca radiata (a species with female philopatry), female offspring appear to be the predominant victims.

4. Discussion

Our findings establish that female infanticide is widespread across mammals and our comparative analyses support the idea that this behaviour is adaptive, even when the target may be related. Infanticide is more likely to occur in species in which multiple adult females live or breed together than where females breed solitarily, and infanticide appears most frequent in species where females only associate temporarily to breed. Because infanticidal behaviour is relatively rare and may be difficult to detect, this association may reflect the fact that opportunities to commit and to observe infanticides may be greater where females live or breed together. Within each type of social organization, we do however find that females, like males, appear to commit infanticide when the presence of the victim might otherwise limit their own reproductive success. While infanticide by males has evolved primarily in response to mate competition across mammals [14,15], the evolutionary determinants of infanticide by females are apparently more complex, as females may compete over multiple resources.

Several lines of evidence indicate that female infanticide is adaptive, with females killing conspecific offspring in response to competition over resources that are critical for successful reproduction. First, infanticide appears associated with variation in ecology and life-history. Specifically, it is most frequently observed in species facing harsh climatic conditions and making the greatest reproductive efforts; it is unlikely that such associations are owing to variations in opportunities to observe or commit infanticides across species. Rather, the potential costs of sharing critical resources might outweigh the risks associated with committing infanticide in such circumstances.

Second, specific determinants of female infanticide identified at the population level by field studies also seem to predict its distribution across species. Extraterritorial infanticides were found to be most frequent in solitary species where females use burrows to give birth and territories to raise offspring, allowing killers to free-up reproductive space for their own offspring. Anecdotal reports suggest that mothers of victims in these species frequently move away after the loss of their offspring [24]. The strong association with burrow use might occur because burrows represent a clear defendable resource, because offspring kept in burrows tend to be altricial [47] and unable to flee or defend themselves, or because infanticide is more easily observed if researchers know where offspring are. Our findings further show that female infanticide occurs in pair breeders where helpers—fathers or additional group mates—are present. A lower number of helpers per offspring reduces their weight and their chances to survive at independence, such that females might even kill offspring born to close kin, such as their grandchildren [48,49]. Finally, patterns are slightly more complex in social breeders. There, infanticide preferentially occurs in species where aggressive competition among females leads to the eviction of some individuals—generally young adults—from the group, especially at times when group size increases (e.g. [50]). In such cases, killing unrelated infants may limit future competition and the related risk of being evicted for the killer's offspring. In addition, in social breeders where females are philopatric, infanticide was only found to occur where female rank acquisition is nepotistic, a hierarchical system where each additional offspring may contribute to strengthen the social status of a matriline—and where infanticide may consequently weaken competing matrilines on the long term. Given that field reports appear to include cases where the victim and the killer might have been related, future studies could usefully document the kinship ties between killers and victims to confirm or refute this scenario.

Anecdotal reports of female pinnipeds killing orphans as they attempted to suckle from them inspired the hypothesis that females compete over milk in species where they only associate to breed [18]. While our comparative analyses did not reveal any difference in the energy content of milk of associated breeders in which infanticide is present versus absent, associated breeders nevertheless comprise the species with the highest energy content of milk and the fastest growth rates, and we further found that offspring are larger at birth and weaned at an earlier age in associated breeders with infanticide compared to those without it. The lack of support for the milk competition hypothesis in our analyses may be explained by a noisy dataset, where the absence of infanticide in some species may be owing to the fact that it goes undetected if it is hard to observe, or to the evolution of counter-adaptations that protect offspring against infanticide. Alternatively, milk is not the only resource over which these females compete. For example, in the large breeding colonies of pinnipeds, space is sometimes very restricted [51], especially in the immediate vicinity of the harem leaders. These bulls often protect their females and calves from attacks by younger males, and may represent another source of competition for lactating females.

It is likely that, in any given species, infanticide may be triggered by more than one determinant—including some that may not be considered here. A killer may accordingly get multiple benefits from one infanticide event, but may also commit infanticides in more than one context. For example, half of the species of pair breeders committing intra-group infanticides also commit extraterritorial infanticides. It is, therefore, possible that different types of female infanticide—following our classification—have followed a common evolutionary path. Specifically, it is possible that infanticidal behaviour initially emerged in response to one particular pressure (e.g. competition over access to allocare) in a given species, which subsequently started to express it in other competitive contexts (e.g. competition over breeding territories). However, the limited number of species for which observational data on infanticide are available, as well as heterogeneities in the sample—such as an over-representation of group-living species—introduce uncertainty when attempting to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the trait. It is consequently hard to infer the ancestral state, whether each infanticide type has evolved independently, or how many times infanticidal behaviour has emerged across mammals. Similar difficulties limit causal inferences regarding the association between infanticide and social organization. In some lineages, the risk of infanticide might prevent breeding females from forming groups, while in others the evolution of infanticide might be favoured by the constraints or opportunities of a specific social system, in line with patterns observed in males [14].

Many female mammals live with related groupmates, suggesting that the threat of within-group infanticide should be low. However, the lack of association between female infanticide and philopatry across species (table 1), as well as a synthesis of observations revealing that killers and victims are commonly related in some contexts, such as in pair breeders where reproductive suppression is common [45], suggest that matrilineality and subsequent increases in average kinship among associated females does not necessarily lead to a reduction in competition among females. Some previous work suggested that mammalian females might be predisposed to behave positively and cooperatively with kin [52], such that species with female philopatry would be characterized by stable social bonds [53]. However, the factors leading to limited dispersal and the spatial association of kin frequently also result in high local competition [54] which can overcome the potential benefits of cooperation among kin [55]. Studies of competition among males in such circumstances have shown that contrasts in levels of aggression can be explained by variation in the potential direct fitness benefits of winning [56], and it is likely that this also applies to the observed pattern of infanticide by females—where the direct benefits of infanticide in terms of increased access to a critical resource might outweigh its costs, including the indirect fitness costs associated with killing related offspring.

Our study compiles five decades of behavioural data across species and within populations to elucidate the determinants of infanticide by mammalian females, which are less well understood than those of male infanticide. Our analyses suggest that the distribution of female infanticide across species reflects contrasts in social organization; infanticide is most frequent in species that breed in groups, which probably have more opportunities for killings and also face greater breeding competition. Female infanticide occurs where the proximity of conspecific offspring directly threatens the killer's reproductive success by limiting access to critical resources for her dependent progeny, including food, shelters, care or a social position. Finally, these data support the idea that female killers occasionally sacrifice related young conspecifics and may therefore actively harm their indirect fitness in order to maximize their direct fitness.

Supplementary material

This submission includes all data in the electronic supplementary material, tables S1 (comparative data) and S2 (population observations), with references for observations on infanticide by females in the electronic supplementary material, File S1, and credits for the animal drawings used in figure 1 in the electronic supplementary material, File S2.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Clutton-Brock, Peter Kappeler, Oliver Höner and Eve Davidian for useful discussions. We are grateful to the editor and two reviewers for constructive feedback and to the organizers of this special issue for inviting us to participate. Contribution ISEM 2019-001.

Data accessibility

All data are provided in the electronic supplementary material and are deposited at the Knowledge Network for Biocomplexity: https://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1ZG6QFR.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, collected and interpreted the data, wrote the article and gave final approval; the analyses were done by D.L. with input from E.H.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

D.L. was supported by the European Research Commission (grant no. 294494-THCB2011 to Prof. T. Clutton-Brock) and the Max Planck Society. E.H. was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (grant no. NE/RG53472 to Prof. T. Clutton-Brock) and during the writing-up of this manuscript funded by the CNRS and ANR (grant no. ANR-17-CE02–0008).

References

- 1.Clutton-Brock T. 2007. Sexual selection in males and females. Science 318, 1882–1885. ( 10.1126/science.1133311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clutton-Brock T, Huchard E. 2013. Social competition and its consequences in female mammals. J. Zool. 289, 151–171. ( 10.1111/jzo.12023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clutton-Brock TH, Huchard E. 2013. Social competition and selection in males and females. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130074 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0074) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stockley P, Bro-Jørgensen J. 2011. Female competition and its evolutionary consequences in mammals. Biol. Rev. Camb. Phil. Soc. 86, 341–366. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00149.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emlen ST, Oring LW. 1977. Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science 197, 215–223. ( 10.1126/science.327542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor RC, Krützen M. 2015. Male dolphin alliances in Shark Bay: changing perspectives in a 30-year study. Anim. Behav. 103, 223–235. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.02.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gowaty PA. 2004. Sex roles, contests for the control of reproduction, and sexual selection. In Sexual selection in primates: new and comparative perspectives (eds Kappeler P, van Schaik C), pp. 37–54. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clutton-Brock TH. 2016. Mammalian societies. New York, NY: Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young AJ, Clutton-Brock T. 2006. Infanticide by subordinates influences reproductive sharing in cooperatively breeding meerkats. Biol. Lett. 2, 385–387. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clutton-Brock TH, et al. 2001. Cooperation, control, and concession in meerkat groups. Science 291, 478–481. ( 10.1126/science.291.5503.478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palombit R. 2012. Infanticide: male strategies and female counter-strategies. In The evolution of primate societies (eds Mitani JC, Call J, Kappeler PM, Palombit RA, Silk JB), pp. 432–468. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hrdy SB. 1974. Male-male competition and infanticide among the langurs (Presbytis entellus) of Abu, Rajasthan. Folia Primatol. 22, 19–58. ( 10.1159/000155616) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Schaik CP, Janson CH. 2000. Infanticide by males and its implications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukas D, Huchard E. 2014. The evolution of infanticide by males in mammalian societies. Science 346, 841–844. ( 10.1126/science.1257226) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palombit RA. 2015. Infanticide as sexual conflict: coevolution of male strategies and female counterstrategies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a017640 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a017640) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hrdy SB. 1979. Infanticide among animals: a review, classification, and examination of the implications for the reproductive strategies of females. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1, 13–40. ( 10.1016/0162-3095(79)90004-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hrdy SB. 1976. Care and exploitation of nonhuman primate infants by conspecifics other than the mother. In Advances in the study of behavior (eds Rosenblatt JS, Hinde RA, Shaw E, Beer C), pp. 101–158. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Digby L. 2000. Infanticide by female mammals: implications for the evolution of social systems. In Infanticide by males and its implications (eds van Schaik CP, Janson CH), pp. 423–446. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumstein D. 2000. The evolution of infanticide in rodents: a comparative analysis, In Infanticide by males and its implications (eds van Schaik CP, Janson CH), pp. 178–197, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrell J, Wolff JO, Ylönen H. 1998. Counter-strategies to infanticide in mammals: costs and consequences. Oikos 83, 507–517. ( 10.2307/3546678) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleiman DG, Malcolm J.. 1981. The evolution of male parental investment in mammals. In Parental care in mammals (eds Gübernick DJ, Klopfer PH), pp. 347–387. Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodall J. 1986. The chimpanzees of Gombe: patterns of behavior. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoogland JL. 1985. Infanticide in prairie dogs: lactating females kill offspring of close kin. Science 230, 1037–1040. ( 10.1126/science.230.4729.1037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman P. 1981. Reproductive competition and infanticide in Belding's ground squirrels and other animals. In Natural and social behavior: recent research and New theory (eds Alexander RD, Tinkle DW), pp. 311–331. New York, NY: Chiron Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Boeuf BJ, Whiting RJ, Gantt RF. 1973. Perinatal behavior of northern elephant seal females and their young. Behaviour 43, 121–156. ( 10.1163/156853973X00508) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilchrist JS. 2006. Female eviction, abortion, and infanticide in banded mongooses (Mungos mungo): implications for social control of reproduction and synchronized parturition. Behav. Ecol. 17, 664–669. ( 10.1093/beheco/ark012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cant MA, Nichols HJ, Johnstone RA, Hodge SJ. 2014. Policing of reproduction by hidden threats in a cooperative mammal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 326–330. ( 10.1073/pnas.1312626111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Digby L. 1995. Infant care, infanticide, and female reproductive strategies in polygynous groups of common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 37, 51–61. ( 10.1007/BF00173899) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Connor RJ. 1978. Brood reduction in birds: selection for fratricide, infanticide and suicide? Anim. Behav. 26, 79–96. ( 10.1016/0003-3472(78)90008-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasser SK, Barash DP. 1983. Reproductive suppression among female mammals: implications for biomedicine and sexual selection theory. Quart. Rev. Biol. 58, 513–538. ( 10.1086/413545) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebensperger LA. 1998. Strategies and counterstrategies to infanticide in mammals. Biol. Rev. 73, 321–346. ( 10.1017/S0006323198005209) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebensperger LA, Blumstein DT. 2007. Nonparental infanticide. In: Rodent societies: an ecological and evolutionary perspective (eds Wolff JO, Sherman P), pp. 267–279. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukas D, Clutton-Brock T. 2017. Climate and the distribution of cooperative breeding in mammals. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160897 ( 10.1098/rsos.160897) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lukas D, Clutton-Brock TH. 2011. Group structure, kinship, inbreeding risk and habitual female dispersal in plural-breeding mammals. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 2624–2630. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02385.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilman H, Belmaker J, Simpson J, de la Rosa C, Rivadeneira MM, Jetz W.. 2014. EltonTraits 1.0: species-level foraging attributes of the world's birds and mammals. Ecology 95, 2027 ( 10.1890/13-1917.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Botero CA, Dor R, McCain CM, Safran RJ. 2014. Environmental harshness is positively correlated with intraspecific divergence in mammals and birds. Mol. Ecol. 23, 259–268. ( 10.1111/mec.12572) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sibly RM, Grady JM, Venditti C, Brown JH. 2014. How body mass and lifestyle affect juvenile biomass production in placental mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20132818 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.2818) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones KE, et al. 2009. PanTHERIA: a species-level database of life history, ecology, and geography of extant and recently extinct mammals. Ecology 90, 2648 ( 10.1890/08-1494.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langer P. 2008. The phases of maternal investment in eutherian mammals. Zoology 111, 148–162. ( 10.1016/j.zool.2007.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barton RA, Capellini I. 2011. Maternal investment, life histories, and the costs of brain growth in mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6169–6174. ( 10.1073/pnas.1019140108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hinde K, Milligan LA. 2011. Primate milk: proximate mechanisms and ultimate perspectives. Evol. Anthropol. 20, 9–23. ( 10.1002/evan.20289) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rolland J, Condamine FL, Jiguet F, Morlon H. 2014. Faster speciation and reduced extinction in the tropics contribute to the mammalian latitudinal diversity gradient. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001775 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001775) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hadfield JD, Nakagawa S. 2010. General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 494–508. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01915.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadfield J. 2010. MCMCglmm: Markov chain Monte Carlo methods for generalized linear mixed models. See cran.uvigo.es/web/packages/MCMCglmm/vignettes/Tutorial.pdf.

- 45.Lukas D, Clutton-Brock T. 2018. Social complexity and kinship in animal societies. Ecol. Lett. 21, 1129–1134. ( 10.1111/ele.13079) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohnot SM. 1980. Intergroup infant kidnapping in Hanuman langur. Folia Primatol. 34, 259–277. ( 10.1159/000155958) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kappeler PM. 1998. Nests, tree holes, and the evolution of primate life histories. Am. J. Primat. 46, 7–33. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clutton-Brock TH, Russell AF, Sharpe LL, Brotherton PNM, McIlrath GM, White S, Cameron EZ. 2001. Effects of helpers on juvenile development and survival in meerkats. Science 293, 2446–2449. ( 10.1126/science.1061274) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodge SJ, Manica A, Flower TP, Clutton-Brock TH. 2008. Determinants of reproductive success in dominant female meerkats. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 92–102. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01318.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kappeler PM, Fichtel C. 2012. Female reproductive competition in Eulemur rufifrons: eviction and reproductive restraint in a plurally breeding Malagasy primate. Mol. Ecol. 21, 685–698. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05255.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baldi R, Campagna C, Pedraza S, Le Boeuf BJ.. 1996. Social effects of space availability on the breeding behaviour of elephant seals in Patagonia. Anim. Behav. 51, 717–724. ( 10.1006/anbe.1996.0075) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Fiore A, Rendall D.. 1994. Evolution of social organization: a reappraisal for primates by using phylogenetic methods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9941–9945. ( 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9941) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silk JB. 2007. Social components of fitness in primate groups. Science 317, 1347–1351. ( 10.1126/science.1140734) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frank SA. 1998. Foundations of social evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 55.West SA, Pen I, Griffin AS. 2002. Cooperation and competition between relatives. Science 296, 72–75. ( 10.1126/science.1065507) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.West SA, Murray MG, Machado CA, Griffin AS, Herre EA. 2001. Testing Hamilton's rule with competition between relatives. Nature 409, 510–513. ( 10.1038/35054057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided in the electronic supplementary material and are deposited at the Knowledge Network for Biocomplexity: https://knb.ecoinformatics.org/view/doi:10.5063/F1ZG6QFR.