Abstract

Matrilineal systems in sub-Saharan Africa tend to co-occur with horticulture and are rare among pastoralists, with the causal arrow pointing from the introduction of cattle to the loss of matriliny. However, most work on this topic stems from either phylogenetic analyses or historical data. To better understand the shift from matrilineal to patrilineal inheritance that occurred among Bantu populations after the adoption of pastoralism, data from societies that are currently in transition are needed. Himba pastoralists, who practice ‘double descent’, may represent one such society. Using multi-generational ethnography and structured survey data, we describe current norms and preferences about inheritance, as well as associated norms related to female autonomy. We find that preferences for patrilineal inheritance are strong, despite the current practice of matrilineal cattle inheritance. We also find that a preference for patriliny predicts greater acceptance of norm violating behaviour favouring sons over nephews. Finally, we show that there are important generational differences in how men view women's autonomy, which are probably attributable to both changing norms about inheritance and exposure to majority-culture views on women's roles. Our data shed light on how systemic change like the shifts in descent reckoning that occurred during the Bantu expansion can occur.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘The evolution of female-biased kinship in humans and other mammals’.

Keywords: double descent, Bantu expansion, matriliny

1. Introduction

The system of descent is one of the key structural features of any human society. In addition to tracing the socially recognized links between members of a family, descent systems commonly regulate the transfer of status and resources, determine appropriate marriage partners and dictate modes of interpersonal affect and behaviour. Schneider [1] further defines a ‘descent group’ as a unit focused on decision-making, controlling how material and embodied resources are mobilized, managed and passed on, and providing a system of enforcement to ensure conformity. Descent systems then relate not only to the actual practices of its members but to the norms that govern them.

Most societies practice unilineal descent with patrilineal systems greatly outnumbering matrilineal ones [2]. While cross-cultural databases tend to classify cultures as having one form of descent or another, it is generally acknowledged that systems of descent (and its sister systems of postmarital residence) are fluid. Ethnographic, linguistic and phylogenetic data have all been used to trace changes in descent over time [3–6]. While these shifts can occur in any direction, the fragility of matrilineal reckoning in particular has been the subject of great debate for nearly a century [7,8]. While some scholars have focused on economic change, market integration and inequality as important forces in the disintegration of matriliny [7–11], others have pointed to conflict engendered when men are torn between their affinal and consanguineal relations, in other words their roles and obligations as uncles/brothers and as husbands/fathers [1,12].

(a). The special case of double descent

While fundamental criticisms about traditional ways of categorizing kin and clan systems persist, anthropologists have continued to rely on Goody's [13] characterization of double descent, which has three key components: the conscious recognition of matrilineal and patrilineal lines of ancestry, the corporate status of groups based on that recognition and the importance of property passed down both lines [13]. Within Africa, double descent is concentrated in a band of Bantu-speaking populations living across central and southeast Africa. It is marked by highly complex sets of ritual and material property rights and statuses differentially held by and transmitted through matrilineal and patrilineal lines of kin. The clear differences between the rights of these sets of heirs arguably entail a consilience of practice in order to minimize conflicts between them. Anthropologists who have written on these societies have pointed to the political consequences of recognizing two lineages, notably the diffusion of lines of authority and the cross-cutting ties that provide unity and dampen the possibility of conflict [14,15]. All current societies with double descent have virilocal residence, which appears to reinforce the unity of the patrilineages. Beyond that, there are few commonalities [13].

Socio-cultural anthropologists writing about double descent have remarked on the conflicting loyalties fathers experience and the efforts they make to pass their property to their sons in place of rightful heirs by matrilineal kinship. Men's efforts to flout what are seen to be ‘inconvenient’ rules of inheritance have included arranging their sons' marriages to patrilateral (FZD) cross-cousins or more distantly related matrikin—with their grandsons expected to benefit from property obligatorily passed to matrilineal heirs [10]. Notably, the same argument was made about matrilineal societies early in the twentieth century [16]. Another long-standing theme in discussions of societies with double descent is how patrilineal inheritance is gaining priority at the expense of property traditionally accruing to matrilineal heirs in the modern day and that these changes are attributable to new economic opportunities and new state institutions [17,18]. This argument also echoes anthropological observations of the vulnerability of matrilineal institutions to changes owing to economic modernization and political centralization, which have led a number of matrilineal societies to shift to neolocal residence and nuclear family organization. Double descent then represents a particularly important system for studying changes to inheritance norms.

(b). Descent and inheritance among Bantu groups

One of the best documented cases of shifting patterns of residence and descent occurred during the Bantu expansion. Around 5000 years ago, as temperatures warmed and agriculture emerged as a dominant mode of production in west-central Africa, there was a massive demographic shift, with Bantu groups in Cameroon and Nigeria expanding to both the east and the south [19,20]. As they shifted to drier areas and interacted with Nilotic- and Cushitic-speaking groups, some Bantu began relying more heavily on domesticated animals, while others, particularly in the south, became full-time pastoralists [21,22]. Phylogenetic analyses point to several shifts in residence and descent during this period, which coincided with changes in the dominant mode of production [6] from the matrilineality frequently found in connection with horticulture to the patrilineality that characterizes pastoralism. In particular, matriliny and pastoralism rarely co-occur, prompting Aberle to remark that the cow was the ‘enemy of matriliny and the friend of patriliny’ [9, p. 680]. Holden & Mace [23] followed up this observation with a more sophisticated analysis, concurring with the original finding and showing a causal link: that the uptake of cattle led to the loss of matrilineal inheritance in many places.

While most Bantu cultures have unilineal systems of descent, there are a few that are characterized as having double descent. Among those included in Holden & Mace's [23] phylogenetic analysis of the Bantu, three are included: Herero (to whom Himba are genetically and culturally closely related), Ovimbundu and Venda. Venda do not appear to meet the standards for dual descent laid out by Goody, as property is not passed through the maternal line [24]. Ovimbundu and Herero both have classic systems of double descent, with land being passed through the patriline and livestock through the matriline ([14] on Herero and [25] on Ovimbundu). That these groups have cattle that is passed matrilineally is particularly interesting, in the light of Aberle and later Holden and Mace's claims that pastoralism typically leads to a shift towards patrilineality. Coupled with their systems of virilocal residence and increasing integration with mainstream markets, these groups may be vulnerable to shifts in their inheritance structures.

(c). Inheritance, autonomy and the role of women

Systems of inheritance are intimately tied to other cultural norms and affect kin relationships and social hierarchies [26,27]. One of the earliest, and most enduring, associations with matriliny is its link to women's autonomy. It should first be noted that matrilineal descent should not be confused with matriarchy, which has not been documented in human societies [1,28]. However, numerous ethnographies have discussed the concurrence of matrilineal descent with greater freedom and power for women [11,29,30]. Others offer a more tempered view, highlighting the importance of male dominance and control, while still noting that women in matrilineal societies generally fare better than their counterparts in patrilineal societies [31,32].

Cross-cultural analyses have shown matriliny to be associated with greater access to divorce and more sexual freedom for women [33–35] and fewer proscriptions on premarital and extramarital sex [36–39]. Hartung [40], in a cross-tabulation, found that men in matrilineal societies had much lower probability of paternity than men in patrilineal groups. These patterns led researchers to believe that there was a causal relationship between the likelihood of paternity and the resulting inheritance pattern, with matriliny arising as an adaptive response to low probability of paternity. However, the level of non-paternity needed to support this theory is far greater than that seen in most human populations, leading both cultural and evolutionary anthropologists to concur that something more than just low paternity must be driving matrilineal preferences [41,42]. Regardless, the literature on matrilineality and female autonomy suggests that transitions to patrilineality would be accompanied by greater restrictions on women's sexuality.

Increased market integration and exposure to capitalist norms have historically been associated with the decline of matriliny and reduced power and authority for women [8,43]. Horticulture, which often co-occurs with matrilineal inheritance, relies heavily on female labour and cooperation between women, giving them more power in the production system [44]. But in recent years, exposure to globalization has been associated with improvements in women's status [45,46]. Market integration could therefore lead to countervailing effects on women's autonomy. On the one hand, the shift towards patriliny that often occurs with modernizing markets could constrain female autonomy, while, on the other hand, the influences of national and global forces promoting women's rights could lead to increases in their access to resources and decision-making power.

(d). Himba pastoralists in the Omuhonga Basin

The Omuhonga Basin is home to several pastoralist and agro-pastoralist groups including Ovahimba, Ovaherero, Ovatjimba, Ovazemba, Hakaona and Twe. Like much of northern Namibia, the area is dry and mountainous, but the Omuhonga, a tributary of the larger, perennial Kunene River, provides access to enough water that the area has become relatively densely populated, supporting both animal husbandry and seasonal gardens. Himba in Omuhonga reside virilocally in extended family compounds, and while they maintain and use cattle posts, some members of the family are almost always present in the main compound (onganda).

(i). Inheritance practice among Himba pastoralists

Himba and Herero are well known for their classic system of double descent [14,47]. Individuals maintain membership in both a matriclan (eanda) and a patriclan (oruzo), with distinct and complementary forms of inheritance passed through each line. The majority of material wealth, which consists of cattle as well as smaller stock, is passed between male members of the matriline, first from a man to his younger brothers and then to his sister's son (ovasya). Other cattle, which have been deemed sacred, tend to be passed from father to son. Typically, sacred cows make up only a small share of the herd; however, there is variation among Himba and Herero as to the percentage of sacred cattle, which in turn affects the predominance of matrilineal inheritance in a particular area [48]. Among Himba in Omuhonga, the present study area, the vast majority of the livestock is passed to matrilineally related kin, with one main heir (okuhita).

While the majority of cattle are inherited matrilineally, resources necessary to maintain a herd are inherited patrilineally, including access to water and pasture and ownership of compounds and cattle posts [47,48]. Control over ritual rights and political offices also are transferred within the patrilineage, although Bollig [48] notes that this represents a recent shift, with the matriline previously holding more political prominence. Moreover, there are important elements of ritual practice and property that are distinctly feminine [49].

(ii). The role of women

Unlike most pastoralist groups, and in line with many matrilineal societies, Himba women maintain a high level of autonomy in marital and reproductive decision-making. Although arranged marriage is common, women are free to initiate divorce, and many marriages are ‘love matches’. In addition to frequent divorce, concurrent partnerships are very common for both men and women, and there are extensive norms in place to maintain marital harmony in the face of extramarital sex [49–51].

Freedom of mobility is also high among women. Virilocal postmarital residence is practiced, but frequent visits to maternal kin help maintain natal support networks and allow women significant support during critical times, particularly around births. Women also may travel throughout the community for funerals and ceremonies and to care for sick relatives. These frequent trips resulted in 50% of women currently residing with natal kin in one cross-sectional census [52].

Less is known about Himba women's role in household decision-making. The sexual division of labour places many tasks squarely in the female domestic domain, though women have little access to cash or markets (except for pension payments paid to elders) and therefore limited access to make decisions about production. Men and women both report that women are often involved in decisions about household dynamics, such as taking a new co-wife and deciding whom a daughter should marry, and the ability to easily divorce means they can remove themselves from a situation that has become untenable for them. Girls are less likely than boys to be sent to school, especially secondary school, probably because their domestic work is more critical to household production, and they marry about 10 years earlier. One area of domestic production where women have more control than men is in the maintenance of gardens. These gardens are passed matrilineally and are often worked by multiple generations, bringing together mothers and daughters who otherwise reside in separate households.

(iii). Market integration and inter-ethnic influences

Integration with the market economy remains limited in Omuhonga, despite ongoing interactions with colonial powers in the region through most of the twentieth century, and after independence in 1990 with the Namibian government. Most recently, veterinary quarantine regulations limit the ability of local herders to participate in wholesale livestock trade, leading to increased marginalization and reliance on subsistence herding [53,54]. However, smaller cattle markets do exist in surrounding towns, and sale of livestock for cash is feasible and often done in order to purchase maize meal or other goods. The sale of livestock is the main access point for integration in the cash economy. Outside of the limited sale of livestock, there is little engagement in migratory work or outside industry.

While Himba in Omuhonga continue to live a largely traditional lifestyle, exposure to the values and norms of other groups occurs in myriad ways. Large gatherings during funerals and ceremonies bring together individuals from multiple ethnic groups. Traders set up at these gatherings, and on other more regular occasions (e.g. at locales where pension payments are paid out) to sell their goods. Travel to larger towns remains infrequent for most people but brings exposure to media, markets and majority-culture norms and practices. Tourists also occasionally travel through Omuhonga and a few households invite tourists to visit, in exchange for cash or food gifts. Cell phone usage is now common, although these are used mainly to communicate with friends and family, rather than for broader access to social media. Despite these changes, electrical power is unavailable in the community, and access to television and other media is still extremely limited.

Himba maintain ethnic markers that distinguish them from neighbouring ethnic groups and from the majority norms that are predominant in town (e.g. western dress, some spoken English). Himba women in particular maintain traditional dress, with little variation other than the types of jewellery they wear. Most men, on the other hand, have integrated western clothing with their traditional wear, particularly in the younger generation. Still, the cultural distinctiveness of Himba dress affords them a level of cultural status not seen in other populations. Himba have attained national and even international recognition as a symbol of Namibian traditionalism, and are often featured prominently in tourism advertisements. While this recognition affords them little in the way of market access, outside of limited involvement in tourism, it does allow for cultural cachet in larger political and ecological decision-making in the greater Kunene region, such as when Himba have used their traditional identity and lifestyle to protest a potential dam being built in the area [55,56].

(e). Rationale for current study

Given the particular precariousness of inheritance patterns in double descent systems and the multiple interactions between market and inter-ethnic exposure, as well as demographic factors, a micro-level study of norm change was conducted among Himba pastoralists. First, we sought to understand the overall degree of preference for patrilineal versus matrilineal inheritance, and to examine how stable these preferences are when considering age and education. We predicted that owing to increasing intercultural interaction and market integration, both of which are associated with greater patriarchal influence and control, younger men will have a stronger preference for patriliny, and years of education will positively associate with patrilineal preferences. Second, we predicted that a preference for patriliny will lead to greater tolerance for inheritance norm violations, which could further erode social norms. Finally, because of the links between the inheritance system and the role of women in society, we predicted that men's perceptions of female autonomy would be affected by their age, level of education and their inheritance preferences.

2. Methods

(a). Study population

For this study, a stratified sample of 51 men all living in Omuhonga were interviewed (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The first group of men was aged 15–25 (mean age 23, n = 17) and had little to no formal schooling (0.9 years on average). The second group was of similar age (mean age 19.3, n = 20) but all were currently enrolled at Omuhonga School, where they board during the week and return home on the weekends. The third group were men 40 and older (mean age of 60.6, n = 14), chosen to represent the viewpoint of fathers who are currently making decisions about inheritance for their own sons. Our sample size was limited by the size of the population and the availability of men in the area, who are often travelling away from camp, but is not atypical for studies in small-scale populations. We chose to focus on men in this study, as they are the main donors and recipients of wealth, as well as the main sanctioning agents. However, we recognize that women's views on inheritance, and particularly autonomy, would serve as an important complement to this work and will be the subject of a future study.

(b). Ethnographic interviews

We conducted one focus group and several individual interviews to learn about Himba views on double descent, inheritance practices and kin relationships within the matriclan and patriclan. The focus group was conducted with three men aged 23, 42 and 69. While age-matched focus groups are preferable to reduce deference by younger individuals, our focus group was opportunistically constructed. Most of the questions for the focus group were objective (e.g. what are the rules for selling sacred and non-sacred cows?) and therefore less prone to deferential bias than more subjective questions. Individual interviews were conducted with 15 men of various ages (16–78) subsequent to the formal survey that was administered separately as part of a life-history interview.

(c). Measure of inheritance preferences

The inheritance preference measure was designed to ascertain which system of inheritance (patrilineal or matrilineal) participants would prefer if either was an option. We first explained to them that unlike the Himba system, there were other places where cattle were transferred from father to son instead of from uncle to nephew. We then asked them to imagine that they could choose which system the Himba would practice and to tell us which they would prefer. Following this, they were asked to explain their choice and free responses were recorded.

(d). Counterfactual inheritance vignette

Participants were presented with a short counterfactual vignette stating that a Himba man decided to give his cattle to his son instead of to his nephew. They were then asked whether or not this action was acceptable. Following that, they were asked what, if anything, would happen to a man if he did this. These free responses were coded into categories. Finally, participants were asked whether they had ever heard of this happening, and if so to describe the event and its consequences.

(e). Female autonomy measures

Three aspects of female autonomy were measured in this study, under the assumption that autonomy is multi-faceted and that shifts in one type of autonomy will not necessarily correlate to changes in others. Each measure was designed to capture men's perception of norms related to female autonomy, rather than their personal behaviour or preferences. The first measure addresses women's role in household decision-making. We adapted a short survey designed for use with pastoralists [57] modified slightly to address the specific decisions made in Himba households (see the electronic supplementary material for questions). These questions asked about who makes decisions in particular domains. A summary score was calculated, with responses for each of seven items ranging from zero (husband only) to four (wife only). Second, we asked several questions about women's freedom of movement. First, we asked how long a wife could visit her natal household without her husband getting upset. Next, we asked four binary questions about whether a wife should be allowed to travel by herself to her natal compound, to a funeral, to the clinic or to the town of Opuwo. These responses were added together for a summary score of female travel. Finally, we asked one question about concurrent partnerships. Men were asked whether or not it was okay for a married Himba woman to have a boyfriend whom she sees regularly and has sex with.

(f). Demographic and descriptive variables

All participants were aged using the traditional name–year system (see [52] for details on this method). To assess the degree of adherence to traditional cultural ethnic markers, we recorded whether participants wore a traditional hat/headpiece (if married), or ponytail (if unmarried), whether they wore trousers or more traditional skirts and whether they had voluntarily participated in dental avulsion. These acculturation markers were recorded as presence/absence, and a summary score was calculated.

To assess degree of traditionalism, participants were shown a series of digital illustrations of men and women dressed in traditional and western attire (table 1). Using these photos as prompts, participants were asked three questions: (i) which of these women would you prefer to marry, (ii) which of these men would you prefer to look like, and (iii) which of these elder men do you respect more? Additionally, participants were asked if they would prefer to live in the village or in town, and if they would prefer to engage in wage labour or herding. Elder men were asked these questions in reference to their sons (e.g. which of these women would you prefer your son to marry?). Responses were coded as traditional/western, and responses summed for an overall traditionalism score.

Table 1.

Traditionalism scores by group. (Online version in colour.)

| question | school | young | old | graphical prompt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: which of the following types of woman would you prefer (your son) to marry? | traditional = 45% western = 55% |

traditional = 82.4% western = 17.6% |

traditional = 92.9% western = 7.1% |

|

| 2: which of these men would you rather look like? | traditional = 35% western = 65% |

traditional = 58.8% western = 41.2% |

traditional = 85.7% western = 14.3% |

|

| 3: Which of these men do you respect more? | traditional = 50% western = 50% |

traditional = 82.4% western = 17.6% |

traditional = 71.4% western = 28.6% |

|

| 4: which kind of job would you like (your son) to have in the future? | herding = 25% wage labour = 75% |

herding = 70.6% wage labour = 29.4% |

herding = 64.3% wage labour = 35.7% |

n.a. |

| 5: where would you prefer (your son) to be living in 10 years? | Omuhonga = 50% Opuwo = 50% |

Omuhonga = 76.5% Opuwo = 23.5% |

Omuhonga = 78.6% Opuwo = 21.4% |

n.a. |

(g). Analyses

Results for inheritance preferences, results of counterfactuals and associated predictors were compared between the three groups. Differences between the young community sample, and the school sample were used to better understand the effects of education on preference and adherence to social norms. One-way ANOVA's with Tukey post hoc comparisons were used to test for differences in traditionalism and ethnic marker scores between these groups. Where homogeneity of variance assumptions were violated, we instead use Welch one-way tests.

A series of logistic regressions were conducted to assess the influence of age and education on inheritance preferences. As a result of intentional recruitment from three separate groups, age was non-normal, and instead was converted to a binary variable. Participation in formal education was virtually non-existent outside of the participants recruited from school; therefore, education was similarly converted to a binary variable. Ethnic marker and traditionalism summary scores were centred for analysis, and included with age and education as predictors of preference. Similarly, to better understand how matrilineal versus patrilineal preference is associated with tolerance for norm violation, preference was used as a predictor in a series of logistic regressions to predict results of the counterfactual for matrilineal inheritance norm violation, with age, education, ethnic marker and traditionalism scores as predictors. Finally, linear regressions to predict traditionalism, ethnic marker scores and female autonomy scores were similarly conducted, to assess the influence of age and education and inheritance preference on these variables.

3. Results

(a). Descriptive statistics

Age and schooling status were both important distinguishing features in our sample. Results from ANOVA comparisons revealed significant differences in traditionalism and ethnic marker scores between groups (F = 5.851, p = 0.005; F = 180.01, p < 0.005, respectively). The two younger groups differed markedly in their preferences for traditional lifestyles (adjusted p = 0.02) and in their ethnic marker scores (adjusted p < 0.005). The school group was also significantly more likely to prefer wage labour over herding as a future career (p = 0.009, odds ratio = 6.76; table 1). The younger non-educated group was indistinguishable from the older men in their traditionalism scores (adjusted p = 0.94) and in their job preferences (p = 0.99), but did differ significantly in their ethnic marker scores (adjusted p = 0.0021). Similarly, regressions to predict these parameters indicate that education, but not age, significantly predicts both ethnic marker and traditionalism score, while age only predicts the former (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

(b). How do inheritance preferences vary across groups?

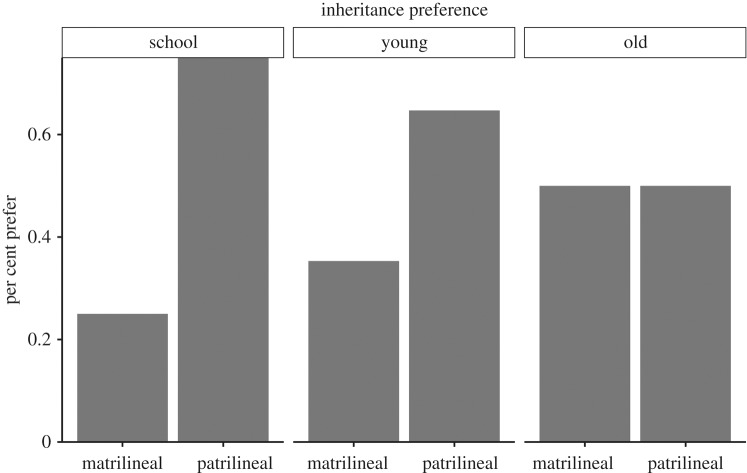

Across the three groups, there were strong preferences for patrilineal inheritance (figure 1). Elder men's preferences were evenly split between the two systems, while the majority of both groups of younger men preferred patriliny (75% for the school youth and 64.7% for those not in school). A logistic regression model was used to determine whether these preferences were affected by participants' traditionalism scores, or by personal motivations linked to their own inheritance prospects (i.e. whether their father or uncle was richer). Neither these, nor age or education, had any significant effect on the preference for patriliny.

Figure 1.

Inheritance preferences by group.

When young men stated a preference for patriliny, they frequently explained their choice as a matter of equity with regard to labour inputs. These men had spent significant time herding the cows of their father, and cited both the emotional and the material connection to the cattle that resulted when explaining why they preferred to inherit patrilineally. As one young man said, ‘The things of your father you worked for and care for, to help him become wealthy. You worked very hard so you should get those cows when he dies’. Another young man referred to the ‘wasted energy’ he put in to caring for his father's cows, because they would be inherited by someone else. Interestingly, these sentiments were shared by both the school group and the non-school group, even though presumably the school group has spent less time actually herding their father's cattle. Another respondent, in explaining why his father was going to give him his cows instead of giving them to the nephew reported, ‘My father said that when he dies I will inherit his compound and he wants to keep the house and the cows together’.

Only 7 of the 51 men explicitly mentioned the stronger kinship link between father and son as an explanation for their patrilineal preference, stating things like, ‘The uncle has his own children who should inherit his things’, and ‘My son is my own blood, so I would prefer to give to him’. By contrast, a few men emphasized the importance of the matriclan in explaining their preference for matrilateral inheritance. One example of such a response is, ‘My father is not my family’.

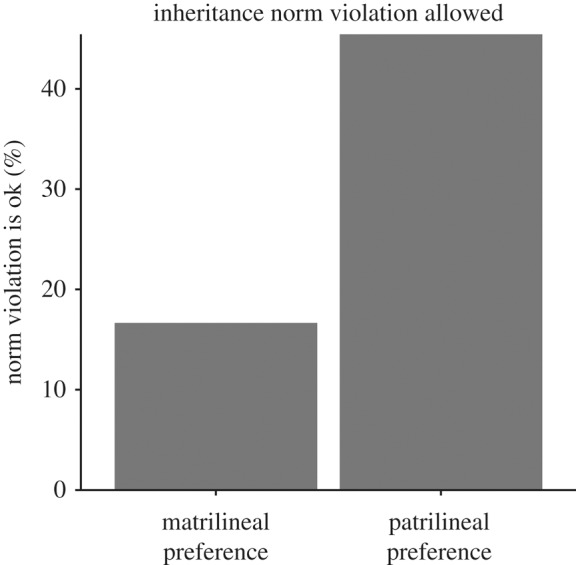

(c). Does inheritance preference predict tolerance for norm violations?

Personal inheritance preference significantly predicted how tolerant men were of norm violations related to inheritance (figure 2). Men who preferred a patrilineal inheritance system were more likely to say that a man giving his cows to his son rather than his nephew was okay in the counterfactual vignette (coef = 1.74, p = 0.025), in a logistic regression with age and education as covariates.

Figure 2.

Inheritance preference predicts tolerance for related norm violations.

(d). What happens when norms are violated?

Sixty-nine per cent of participants reported that they had knowledge of a case where a man diverted his inheritance to his own child, instead of giving to his nephew. Two of the young men in our sample reported that they either had or would be receiving cows from their father and one older man reported that he intended to split his cows 50/50 between his sons and his nephew.

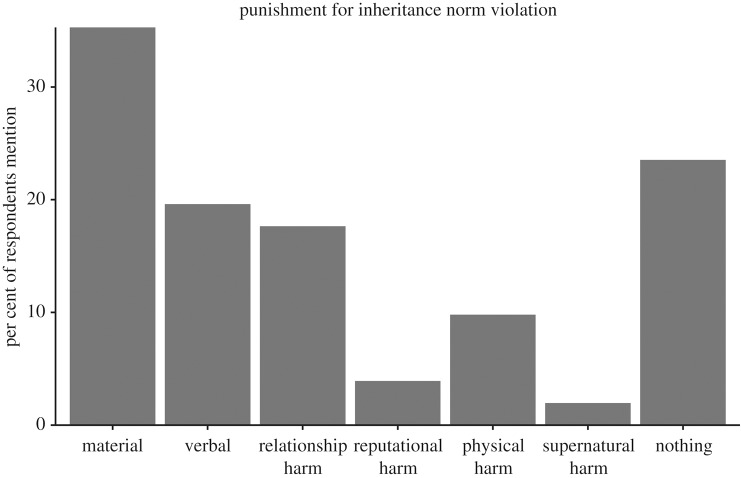

While norm violations appear frequent, sanctioning is also common (figure 3); 76.5% of participants stated that there would be some kind of punishment if a man bequeathed his cows to his son instead of his nephew. The most frequent form of sanction was for the nephew or his family to come and take the cows back from the son (mentioned by 35.3% of participants). Many participants also noted that there would be damage to family relationships, which could sometimes be irreparable.

Figure 3.

Punishment types reported for hypothetical inheritance norm violation.

Despite the frequency with which people reported that inheritance norm violations would be sanctioned, there appears to be considerable flexibility in how cattle are distributed and whether and to what extent, there will be retribution for breaking with the norm. Several men mentioned that before a man dies, it is possible for him to specify that a certain portion of his cattle will go to his children. One man explained, ‘You have to give to both, not just to the son. You could give half to each but the nephew must get some. When you are alive you must decide and tell them [the son and nephew]. Even the cows from the matriclan can be given to the son, some of them. It's up to the person’. Another man told the story of a man who, before he died, gave a cattle post and a portion of his cattle to his son. Because the uncle had a good relationship with the son, he did not try to take them back. In another case, a man explained, ‘A rich man before he died decided his cattle would go to his son. After the funeral the family came to complain because they wanted their share. They agreed to divide them and the son was left with something’.

(e). Are attitudes towards female autonomy related to preferences for patrilineal inheritance?

ANOVA comparison of scores on the female decision-making survey indicate significant differences by group (F = 3.401, p = 0.04), where participants currently in school believe women should have considerably more decision-making power within the household than do the older non-educated group (adjusted p = 0.037). Using regression, age (coef = −0.27, p = 0.049) and education (coef = 0.29, p = 0.0188) independently significantly predict deviation in decision-making scores. However, when both are included in the same model, these predictors fail to reach significance, probably owing to the strong correlation between age and education (electronic supplementary material, table S4). Preference for patriliny does not exert a significant effect on decision-making scores, with or without other predictors.

The length of natal visit allowed was coded into days, and log transformed to correct for extreme outliers. The mean length of natal visit did not differ between groups, nor did age or education predict length of visit (table 2), although older men were most permissive, with an average of 52.4 days allowed compared to 22.8 and 38.4 days, respectively, for the school and young community sample. Likewise neither age nor education predicted the female mobility score, which summed tolerance for different types of female travel. Stated preference for patriliny negatively predicted permissiveness for female travel (coef = −0.46, p = 0.0233).

Table 2.

Female autonomy results by group.

| school | young | old | |

|---|---|---|---|

| decision-making | mean = 11 s.d. = 2.92 range = 4–15 |

mean = 9.44 s.d. = 2.53 range = 5–13 |

mean = 8.43 s.d. = 3.25 range = 4–13 |

| mobility | mean = 2.1 s.d. = 1.52 range = 0–4 |

mean = 1.59 s.d. = 1.58 range = 0–4 |

mean = 2.57 s.d. = 1.5 range = 0–4 |

| extramarital sex norm | ok = 25% not ok = 75% |

ok = 11.8% not ok = 88.2% |

ok = 50% not ok = 50% |

Finally, men were asked about the norm of female concurrent partnerships. Overall, 27.5% of participants said that it was ‘okay’ for a married Himba women to regularly sleep with her boyfriend, but responses were group-specific (table 2). Among the school aged group and young herding group, 25% and 11.8%, respectively, said it was okay, compared with the older group where 50% said it was okay. Using logistic regression, age, but not education or preference for patriliny, predicts responses as to whether female extramarital infidelity is okay (coef = 2.05, p = 0.0279).

4. Discussion

Through our analysis of both structured survey data and ethnographic interviews, we find substantial support for the view that the Himba system of inheritance is in a state of disequilibrium. Whereas the current norm and predominant behaviour is for cattle to be passed matrilineally, men's preferences are for a patrilineal system. Norm violations that favour father to son inheritance are increasingly preferred by the younger generation, and 69% of men in our sample had knowledge of such violations occurring. On the one hand, sanctions remain strong and have a significant impact on the ability of men to subvert the system and shift wealth to their offspring, but workarounds are available and can lead to resolutions that divert at least some wealth from nephews to sons.

(a). Why are preferences shifting towards patrilineal inheritance?

Our study is not the first to presume that Himba inheritance practices are shifting, or that their double decent system is in a transitional state. Malan wrote of the Himba in 1973, ‘…it still appears to be only a temporary stabilized period within a gradual process of change from matrilineality to patrilineality’ [47, p. 103]. Studies of changes to Herero systems of inheritance shed further light. While older works describe a system of double descent very similar to that of Himba, as Herero moved further east and became more integrated with cattle markets and the patriarchal political influences of colonial powers, their norms of inheritance have increasingly favoured patrilineal kin. Vivelo writes, ‘It is not difficult to imagine that when the influence of the elder Herero passes with their deaths, the custom of inheritance by the ZS will soon follow’ [58, p. 177].

Our focus is on understanding shifts in norms and preferences among Himba, whose cultural identity remains strongly grounded in the system of double descent. By comparing three distinct groups of Himba men, we were able to look at the effects of both age and education on inheritance preferences. The school group was markedly different from both the young and old herding men, in terms of both their ties to traditional lifestyles and in their ethnic markers. Despite these differences, the younger groups are remarkably similar in their preference for patrilineal inheritance, and neither group differs significantly from the elder men. Therefore, while we see age- and education-related trends towards an increasing preference for patrilineal inheritance, neither predictor is overwhelmingly convincing as a key driver of change.

An alternative explanation is that the preference for patrilineal inheritance has been relatively stable across generations, and is representative of some of the longer-term conflicts found in both matrilineal and double descent systems. With double descent and virilocal residence, men must raise and care for their children (and in the case of Himba pass down land and customary rights to their sons), while they also bear responsibility and ultimately provide inheritance for, their sister's children.

Where wealth is partible or involves different kinds of resources, men in matrilineal and double descent societies may be able to use inheritance norms strategically to strengthen ties to both their sons and nephews successfully, that is, without engendering resentment or conflicting loyalties [26]. Where cousin marriage is possible, the same results can be obtained. But where one type of lineal heir is consistently advantaged over the other, resentments can mount, criticisms of traditional practices can build and pressures to subvert traditions can culminate in social change. In our data, we see evidence that fathers are making such decisions while they are still alive, allocating particular cattle to their sons and reserving others for their brothers or nephews.

While preferences for patrilineal inheritance may be fairly stable and a result of long-standing conflicts about inheritance in a double descent system, recent economic and social transitions could lead to those preferences manifesting in greater changes in practice in coming generations. Access to education and wage labour have only recently become readily accessible (e.g. the local school opened in 1998), and we do see strong preferences among the school group to work in wage labour rather than herding. In several matrilineal systems, integration with markets and increasing wage labour and wealth inequities have led to the displacement of matrilineal preferences and shifts from large matrilineal grant families to nuclear families [7,59]. Wealth accumulated through wage labour would presumably not be subject to the same rules of inheritance as exist for cattle and traditional lands, and would probably be passed directly to wives and children. Greater engagement with the market economy could then allow young men the freedom to thwart traditional norms and suffer lesser consequences for norm violations. Alternatively, and somewhat counterintuitively, greater dependence on the labour market could free young men to be more agnostic towards the traditional inheritance system, because the stakes are not as high for them.

(b). Are inheritance norms linked to broader perceptions of womens' autonomy?

The Himba system of double descent has features that can both help and hinder female autonomy. Like many matrilineal societies, Himba women enjoy significant sexual freedoms, including the ability to maintain concurrent partnerships, to divorce and to exert partner choice, both in their informal relationships and through ‘love match’ marriages [50]. As descent systems move from matrilineal to either patrilineal or bilateral, reckoning of kinship restrictions on female sexuality tend to arise. Our data show shifts in tolerance for extramarital sex that indicate a change, but we found no direct link between inheritance preference and tolerance for concurrency. We did find that younger men were less tolerant of concurrency than were elders, and there are multiple plausible explanations for this. Younger mens' lower tolerance for concurrency could be the result of exposure to majority-culture norms, which in Namibia largely favour nuclear families and fidelity, particularly for women [60]. In this case, young mens' ideas about the traditional inheritance structure may be less influential to their views on female sexuality than their exposure to the larger cultural complex that comes with market integration. Alternatively, younger men may be less tolerant of concurrency simply because they have more of their reproductive careers ahead of them, making jealousy more profitable to them at this stage of life.

(c). Does a shift in inheritance mean the end of matriliny for Himba?

Early discussions of matriliny discussed it as an adaptation to less intensive forms of production (e.g. horticulture) and abundant and relatively evenly distributed resources. Similar arguments have been made by anthropologists. It has also been argued that matriliny can persist under variable forms of residence, modes of production and sociopolitical systems, even while the strength and form of matrilineal inheritance might be adjusted to fit these new conditions [7–9]. In this way, the overall system of matriliny is malleable and as the system adapts, pieces of it (e.g. descent or residence) might gain or lose strength. This seems to be what we are seeing among Himba. While our data show that there are significant and fairly stable preferences for patrilineal inheritance, and frequent violations of the matrilineal inheritance norm, the importance of matriliny as an overall part of the inheritance system remains strong. When men discussed how norm violations were dealt with, they frequently mentioned that some cows were allocated to sons, but that these transfers involved discussions between the two families to ensure that such arrangements did not irreparably damage their relationships. In our vignette, which did not specify such preconditions, fighting between families was frequently mentioned as a likely response. It should be noted that this represents a shift from Bollig's reports on the same area, as he notes, ‘All Himba however agree on the fact that matters pertaining to inheritance should be addressed only after the death of the person’ [48].

Another way that the double descent system might support continued matrilineal ties in the face of increasing patrilineal wealth inheritance is through levirate marriage. When a man dies, his heir (brother or nephew) has the obligation to care for the orphans of the deceased (e.g. his sons). This often includes cattle loans, effectively maintaining matrilineal inheritance while providing access to the inheritance by the patrilineal heir [48]. It is not hard to see how a system with extensive cattle loans like this could transform from usufruct rights to complete transferral of ownership from the nephew to the son.

5. Conclusion

The literature on matriliny has long been focused on its peculiarities: why it is so rare, what conditions allow it to arise and persist, and what causes the breakdown of particular elements of the system. As such, anthropologists formulated constructs like the ‘matrilineal puzzle’; some highlighting cases where conflicts between affinal and consanguineal kin contributed to the disintegration of matriliny, and others emphasizing its resilience even in the face of widespread economic and sociopolitical change. Double descent, which places even greater emphasis on the maintenance of kin ties along both lines, can be viewed as an extreme form of the matrilineal puzzle, making it an ideal system for understanding how its elements can, synchronously or not, change over time. In providing details on both the norms and the behaviours of Himba men in Omuhonga, we see both elements of the conflict (e.g. strong preferences for patrilineal inheritance across generations) and the ways in which everyday practice manifests to deal with these conflicts. While the Himba system of inheritance does appear to be in a state of disequilibrium, which may in coming years be amplified as market integration and inter-ethnic interactions increase, we expect at least some elements of the double descent system to persist. As the strength of kin ties through one line gains greater prominence, the obligations held by kin related in other ways may diminish. However, this would not mean the elimination of alternative kin ties, only their reformulation in ways that are more consistent with social and economic realities at a given point in time. In the past, in the absence of strong, centralized governments, double descent offered a multiplicity of social connections that enabled the recognition of kin ties across lightly populated regions and a way of mediating conflicts. That may no longer be a priority under modern conditions, but it remains to be seen how these ties of kinship will be conceptualized in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the families living in Omuhonga for their continued support. John Jakurama, Cancy Louis and Gita Louis and Calvin Mukuejuva served as research assistants for the project. We would also like to thank all of the participants of the Matriliny Workshop, held at University of New Mexico in 2017.

Ethics

This research was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (no. 10-000238). All participants provided oral consent.

Data accessibility

Primary data and the R code used for analysis are available at Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/z4eb2/.

Authors' contributions

B.A.S., S.P.P. and N.E.L. all contributed to the conception and design of the study. B.A.S. and S.P.P. collected the data and performed statistical analyses. B.A.S., S.P.P. and N.E.L. all contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

B.A.S. and S.P.P. were funded by NSF-BCS-1534682.

References

- 1.Schneider DM. 1961. The distinctive features of matrilineal descent groups. In Matrilineal kinship (eds Schneider DM, Gough K), pp. 1–29. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murdock GP, White DR. 1969. Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology 8, 329–369. ( 10.2307/3772907) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hage P. 1998. Was proto-oceanic society matrilineal? J. Polyn. Soc. 107, 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lancaster CS. 1971. The economics of social organization in an ethnic border zone: the Goba (northern Shona) of the Zambezi Valley. Ethnology 10, 445–465. ( 10.2307/3773176) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marck J. 2008. Proto Oceanic society was matrilineal. J. Polynesian Soc. 117.4, 345–382. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opie C, Shultz S, Atkinson QD, Currie T, Mace R. 2014. Phylogenetic reconstruction of Bantu kinship challenges main sequence theory of human social evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17 414–17 419. ( 10.1073/pnas.1415744111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gough K. 1961. The modern disintegration of matrilineal descent groups. In Matrilineal kinship (eds Schneider DM, Gough K), pp. 631–652. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglas M. 1969. Is matriliny doomed in Africa. In Man Africa (eds Douglas M, Kaberry PM, Forde CD), pp. 121–135. London, UK: Tavistock Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aberle DF. 1961. Matrilineal descent in cross-cultural perspective. In Matrilineal kinship (eds Schneider DM, Gough K), pp. 655–727. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goody J. 1967. The social organisation of the Lo Wiili. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poewe KO. 1979. Women, horticulture, and society in sub-Saharan Africa: some comments. Am. Anthropol. 81, 115–117. ( 10.1525/aa.1979.81.1.02a00240) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards A. 1950. Some types of family structure amongst the central Bantu. In African systems of kinship and marriage (eds Radcliffe-Brown AR, Forde D.), pp. 206–251. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goody J. 1961. The classification of double descent systems. Curr. Anthropol. 2, 3–25. ( 10.1086/200156) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson GD. 1956. Double descent and its correlates among the Herero of Ngamiland. Am. Anthropol. 58, 109–139. ( 10.1525/aa.1956.58.1.02a00080) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris R. 1962. The political significance of double unilineal descent. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. G. B. Irel. 92, 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuper A. 1988. The invention of primitive society: transformations of an illusion. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forde D. 1950. Double descent among the Yako. In African systems of kinship and marriage (eds AR Radcliff-Brown, D Forde), pp. 85–332. London, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harpending H, Pennington R. 1990. Herero households. Hum. Ecol. 18, 417–439. ( 10.1007/BF00889466) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Filippo C, Bostoen K, Stoneking M, Pakendorf B. 2012. Bringing together linguistic and genetic evidence to test the Bantu expansion. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 3256–3263. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.0318) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden CJ. 2002. Bantu language trees reflect the spread of farming across sub-Saharan Africa: a maximum-parsimony analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 793–799. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.1955) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver R. 1982. The nilotic contribution to Bantu Africa. J. Afr. Hist. 23, 433–442. ( 10.1017/S0021853700021289) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillipson DW. 1977. The later prehistory of eastern and Southern Africa. New York, NY: Holmes & Meier Pub. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden CJ, Mace R. 2003. Spread of cattle led to the loss of matrilineal descent in Africa: a coevolutionary analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 2425–2433. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2535) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuper A. 1979. How peculiar are the Venda? L'Homme. 19, 49–72. ( 10.3406/hom.1979.367928) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCulloch M. 2017. The Ovimbundu of Angola: west Central Africa. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolyanatz A. 1996. Musings on matriliny: understandings and social relations among the Sursurunga of New Ireland. In Gender kinship and power: a comparative interdisciplinary history (eds MJ Maynes, A Waltner, B Sound, U Strasser), p. 81 New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goody J, Goody JR. 1976. Production and reproduction: a comparative study of the domestic domain. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamphere L. 1974. Strategies, cooperation, and conflict among women in domestic groups. In woman culture and society (eds MZ Rosaldo, L Lamphere), pp. 97–112. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dube L. 1993. Who gains from matriliny? Men, women and change on a Lakshadweep island. Sociol. Bull. 42, 15–36. ( 10.1177/0038022919930102) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin MK, Voorhies B. 1975. Female of the species. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlegel A. 1972. Male dominance and female autonomy: domestic authority in matrilineal societies. New Haven, CT: Human Relations Area Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn N. 1977. Anthropological studies on women's status. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 6, 181–225. ( 10.1146/annurev.an.06.100177.001145) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry H. 2007. Customs associated with premarital sexual freedom in 143 societies. Cross-Cult. Res. 41, 261–272. ( 10.1177/1069397107301977) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gluckman M. 1950. Kinship and marriage among the Lozi of Northern Rhodesia and the Zulu of Natal. In African systems of kinship and marriage (eds AR Radcliffe-Brown, D Forde). London, UK: Oxford University Press.

- 35.Hendrix L, Pearson W Jr. 1995. Spousal interdependence, female power and divorce: a cross-cultural examination. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 26, 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barry H, Schlegel A. 1986. Cultural customs that influence sexual freedom in adolescence. Ethnology 25, 151–162. ( 10.2307/3773666) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hua C. 2001. A society without fathers or husbands: the Na of China. New York, NY: Zone Books; (cited 17 June 2014). See http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/society-without-fathers-or-husbands/?cr=reset. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuller CJ. 1976. The Nayars today. CUP Archive. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gough EK. 1959. The Nayars and the definition of marriage. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. G. B. Irel. 89, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartung J. 1985. Matrilineal inheritance: new theory and analysis. Behav. Brain Sci. 8, 661–670. ( 10.1017/S0140525X00045520) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fortunato L. 2012. The evolution of matrilineal kinship organization. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 4939–4945. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.1926) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mattison SM. 2011. Evolutionary contributions to solving the ‘Matrilineal Puzzle’. Hum. Nat. 22, 64 ( 10.1007/s12110-011-9107-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nongbri T. 2000. Khasi women and matriliny: transformations in gender relations. Gend. Technol. Dev. 4, 359–395. ( 10.1177/097185240000400302) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boserup E. 1970. Women's role in economic development. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 53, 536–537. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moghadam VM. 2007. From patriarchy to empowerment: women's participation, movements, and rights in the Middle East, North Africa, and south Asia. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards DL, Gelleny R. 2007. Women's status and economic globalization. Int. Stud. Q. 51, 855–876. ( 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00480.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malan JS. 1973. Double descent among the Himba of south West Africa, vol. 2 Windhoek, Namibia: State Museum. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bollig M. 2005. Meanings of inheritance. In Perspectives on Namibian inheritance practices (ed. R Gordon), p. 45. Windhoek, Namibia: Legal Assistance Centre. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Wolputte S. 2016. Sex in troubled times: moral panic, polyamory and freedom in north-west Namibia. Anthropol. South Afr. 39, 31–45. ( 10.1080/23323256.2016.1147967) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scelza BA. 2011. Female choice and extra-pair paternity in a traditional human population. Biol. Lett. 7, 889–891. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0478) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scelza BA, Prall SP. 2018. Partner preferences in the context of concurrency: what Himba want in formal and informal partners. Evol. Hum. Behav. 39, 212–219. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2017.12.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scelza BA. 2011. Female mobility and postmarital kin access in a patrilocal society. Hum. Nat. 22, 377–393. ( 10.1007/s12110-011-9125-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bollig M. 1998. The colonial encapsulation of the north-western Namibian pastoral economy. Africa 68, 506–536. ( 10.2307/1161164) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bollig M. 2013. Social–ecological change and institutional development in a pastoral community in north-western Namibia. In Pastoralism in Africa: past, present and future (eds H Bollig, M Schnegg, H-P Wotzka), pp. 316–340. New York, NY: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bollig M. 2011. Chieftaincies and chiefs in northern Namibia: intermediaries of power between traditionalism, modernization, and democratization. In Elites and decolonization in the twentieth century (eds J Dülffer, M Frey), pp. 157–176. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meissner R. 2005. Interest groups and the proposed Epupa Dam: towards a theory of water politics. Politeia 24, 354–369. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brunson EK, Shell-Duncan B, Steele M. 2009. Women's autonomy and its relationship to children's nutrition among the Rendille of northern Kenya. Am. J. Hum. Biol. Off. J. Hum. Biol. Assoc. 21, 55–64. ( 10.1002/ajhb.20815) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vivelo FR. 1977 The hero of western Botswana: aspects of change in a group of Bantu-speaking cattle herders, vol 61. Eagan, MN: West Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mattison SM. 2010. Economic impacts of tourism and erosion of the visiting system among the Mosuo of Lugu lake. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 11, 159–176. ( 10.1080/14442211003730736) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mufune P, Kaundjua MB, Kauari L. 2014. Young people's perceptions of sex and relationships in northern Namibia. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 5, 279–295. ( 10.18357/ijcyfs.mufunep.522014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Primary data and the R code used for analysis are available at Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/z4eb2/.