Abstract

Fungal infections as a result of freshwater exposure or trauma are fortunately rare. Etiologic agents are varied, but commonly include filamentous fungi and Candida. This narrative review describes various sources of potential freshwater fungal exposure and the diseases that may result, including fungal keratitis, acute otitis externa and tinea pedis, as well as rare deep soft tissue or bone infections and pulmonary or central nervous system infections following traumatic freshwater exposure during natural disasters or near-drowning episodes. Fungal etiology should be suspected in appropriate scenarios when bacterial cultures or molecular tests are normal or when the infection worsens or fails to resolve with appropriate antibacterial therapy.

Keywords: mycoses, freshwater, eye infections, fungal, keratitis, otitis externa

In previous publications, we have discussed fungal infections resulting from exposure to soil as well as home and yard environments.1,2 In this third article of the series, we will review the much less common occurrence of human fungal infections resulting from freshwater exposure. These infections often involve immunocompromised hosts, but may occur following water-associated trauma (either in freshwater or in the presence of freshwater such that associated organisms may enter the body).3 Some are more common diseases, such as tinea pedis, while others are rare “niche” infections.3,4

As with our previous two articles, this narrative review is not intended to relate detailed diagnostic or treatment information for the diseases discussed. Rather, it is meant to provide the clinician with awareness of freshwater as a potential exposure site for certain fungal infections such that appropriate exposure histories are taken and important diagnoses and etiologies are considered. There are examples of nosocomial water-related fungal infections, particularly in patients with immunodeficiency,cf.5,6 or those specifically involving household plumbing (covered previously).2 However, we will restrict this report to diseases acquired from freshwater sources in the natural environment or more generally from tap water. Additionally, while water-related fungal infections from developing nations may be used as examples, this review will focus on diseases that would potentially occur in developed nations like the United States.

Freshwater Microbiology

Terrestrial freshwater includes groundwater, lakes, rivers, streams and wetlands (and ice, which generally does not serve as a source of infection).7–9 Only the first four entities contribute to private and municipal sources of drinking water. All except groundwater afford opportunities for exposure to infectious microorganisms through recreational and occupational activities. Freshwater microbiomes are complex, interdependent and affected by various gradients within the particular bodies of water; these include oxygen, sunlight, temperature, nutrients, pH and other gradients.8,9

It is noteworthy that ecologist E. C. Pielou, in her popular book on freshwater, fails to mention fungi as members of the microscopic communities.7 Indeed, fungal microorganisms are much less common in freshwater biomes predominated by bacteria (often in biofilms), cyanobacteria, archaea, algae, viruses and protozoa (the latter two important limiters of the bacterial and algal populations).7,9 Nonetheless, microscopic fungi are present in freshwater communities, although they exist in relatively lower concentrations, are rarely planktonic (free-living) and are even more rarely pathogenic.4,9,10 Most are parasitic of planktonic algae or rotifers or are surface colonizers.9

Like Legionella pneumophila and other bacteria, fungi may be associated with or be harbored by free-living amoebas in freshwater, including tap and potable water. The importance of this association is still being elucidated.11 In addition to adjacent soil, one source of freshwater fungi is atmospheric dust (dispersed by wind, excavation and other soil-disturbing activities). One would expect regional variations in species diversity, as documented for dust-associated fungi by external surface cultures.12 A variety of potentially pathogenic fungi may be found in various bodies of water (Figure 1), sometimes as the result of runoff or sewage contamination.cf.13–15

Figure 1.

Representative surface body of freshwater. New fungi may enter the water from upstream, from adjacent shoreline, from atmospheric dust and from animal contact.

Tap water is a potential site of pathogenic fungal contamination and may be a particular concern even in urban areas of developing nations.cf.16 Depending on the municipality, or private water source owner, a variety of methods may be used to remove potentially harmful microorganisms from the water supply.17 In the United States, where drinking water is considered “among the safest in the world,”17 the most common methods to treat community water supplies (particularly when the source is surface water, which is generally more prone to significant contamination then groundwater)10 include coagulation and flocculation (positively charged chemicals are added to bind with negatively charged dirt and other particulate matter), sedimentation of these now larger particles, filtration using natural and artificial filters, and disinfection with chemicals such as chlorine or chloramine (often done as the final step in water purification).17 Nevertheless, pathogenic fungi can still enter drinking water in developed nations, including all types of treated tap and bottled water.10

Pathogenic fungi generally associated with tap water or that have the potential for concern include Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Exophiala dermatitidis and microsporidia.10,18 Chaetomium species have been found frequently in tap water; however, potentially serious infections of immunocompromised patients likely originated from a source other than drinking water.19 The presence of some fungal contaminants in drinking water may be related to their establishment of biofilms in portions of the water distribution system upstream from household or commercial establishment plumbing systems.10 Hageskal et al. provided an informative review of the methodological challenges and difficulty in interpretation of microbiological assessments for drinking water contamination by fungi.10

There are several examples of isolations of potentially pathogenic fungi from municipal water, including sites in Portugal,20 Norway,21,22 Brazil6 and the Netherlands.23 Genera included Penicillium, Aspergillus, Acremonium, Trichoderma, Cladosporium, Paecilomyces and Mycelia.6,20–23 A study of Fusarium in a Houston, Texas, hospital’s water supplies following an outbreak in cancer patients revealed frequent culture of this organism from hospital showers and drains, but no free-living organisms from the hospital drinking water.24 It was believed the source of the organism was from the external environment.24

Eye Infections from Freshwater

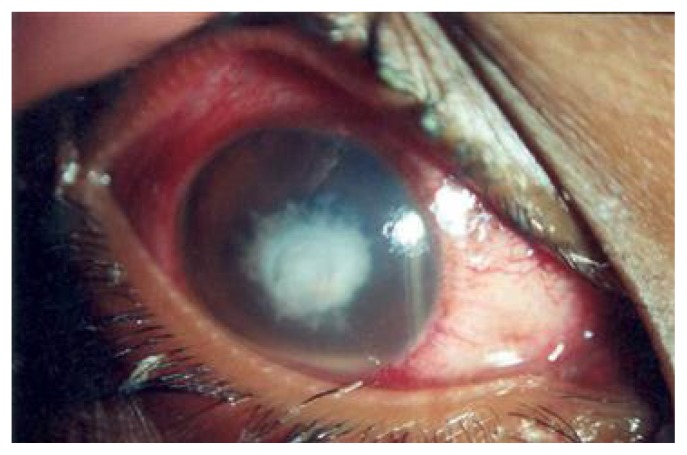

Fungal eye infections acquired directly from freshwater appear to be rare. Those with fungal keratitis present with pain, redness, decreased visual acuity, photophobia, and increased tearing and discharge from the affected eye.25 Eyelids also may be infected and demonstrate blepharospasm, and the cornea may be hazy or have an area of opacification (Figure 2).25 Presumptive keratitis should be confirmed through a slit lamp examination. Identification of the causative organism is generally through culture with or without biopsy,25 but perhaps more appropriately with molecular techniques.26 Ophthalmological treatment generally includes a topical antifungal (typically 5% natamycin) with or without topical amphotericin B or systemic antifungals.25,26 Debridement or more extensive surgery may be required.25 Therefore, all cases should be managed by an ophthalmologist trained in the diagnosis and treatment of these difficult infections.

Figure 2.

Fungal keratitis. (Republished with permission of Macmillan Publishers Ltd., from Thomas PA. Fungal infections of the cornea. Eye. 2003;17(8):852–62.)

Trauma is the inciting factor in approximately half of fungal keratitis cases.25 Predisposing factors include immunosuppression (including that caused by acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS]), diabetes mellitus, preexisting ulceration or other ocular surface disease, lid margin notches, inability to close eyelids (e.g. Bell’s palsy), decreased lacrimation, decreased lacrimal immunoglobulin-A levels, refractive keratotomy and other procedures, and use of contact lens, especially with extended-wear lenses.25,27 Fungal keratitis is much more common in developing countries.25,26 There is significant geographic variation, even within the same country, regarding the proportion of keratitis that is fungal and the proportional distribution of the various fungal genera as etiologic agents.26,27 Filamentous fungi, especially Fusarium and Aspergillus, are the primary causes of fungal keratitis in most parts of the world.25 The former is especially predominant in tropical and subtropical regions.26 Other agents include dematiaceous (dark-pigmented) fungi, Scedosporium apiospermum (discussed in more detail on page 36) and other molds.28

In the United States, Candida species were the predominant causes of fungal keratitis in a New York series and were much more common than Fusarium or Aspergillus.27 A single institution study, 1999–2008, from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, documented an increase in the number of fungal keratitis cases from 2004 to 2008,29 perhaps in association with an outbreak associated with a particular contact lens solution.30 In this series, contact lens-related cases outnumbered those due to trauma, and Fusarium was the dominant genus.29 Four of the 28 contact lens-related fungal keratitis cases had specific water exposure (two from lakes and one each from well water exposure and swimming while wearing contact lenses),29 illustrating the difficulty of sorting out potential etiologic factors such as aqueous lens solution processing, other water exposure and lens trauma. A recent genetic study of 75 clinical and 156 environmental isolates of Fusarium keratoplasticum revealed that clinical and plumbing biofilm isolates were indistinguishable; upstream water sources of contamination were not identified.31

Microsporidia, a diverse group of several genera that are intracellular spore-forming microorganisms recently reclassified as fungi, may be emerging as causes of fungal keratoconjunctivitis in immunocompromised and normal hosts (often in contact lens users).32,33 A large outbreak of microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis occurred following heavy rain during a rugby tournament in Singapore, and a potential association with muddy water exposure was made.34 An outbreak of acute conjunctivitis with episcleritis and anterior uveitis in Brazil was epidemiologically and microscopically linked to freshwater exposure to Emmonsia species (adiaspiromycosis). Risk factors included diving underwater and visiting a particular beach.35

Exogenous endophthalmitis follows penetrating ocular trauma in about 5% of cases; 10% or more of these cases may have a fungal etiology.25 Fusarium and Candida are common causes among the variety of implicated species.25,36 Risks of such infection include neutropenia, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS and intravenous drug abuse. Symptoms include pain, redness and decreased or blurred vision. Common signs are global surface hyperemia and occasional hypopyon.25 Diagnosis and treatment should be performed by an experienced ophthalmologist.

Fungal Acute Otitis Externa

There is reasonable evidence for acute otitis externa (AOE) occasionally being caused by fungi from freshwater. This entity is generally characterized by symptoms of ear pain, typically worsened by manipulation of the tragus or pinna; itching, often as a preceding symptom; and sometimes hearing loss or sense of fullness or blockage in the ear.37 Signs include ear canal erythema and edema, with varying amounts of debris or otorrhea.37 Studies suggest that the aforementioned symptoms, hearing loss and lack of fetid discharge may particularly characterize fungal otitis externa.38,39

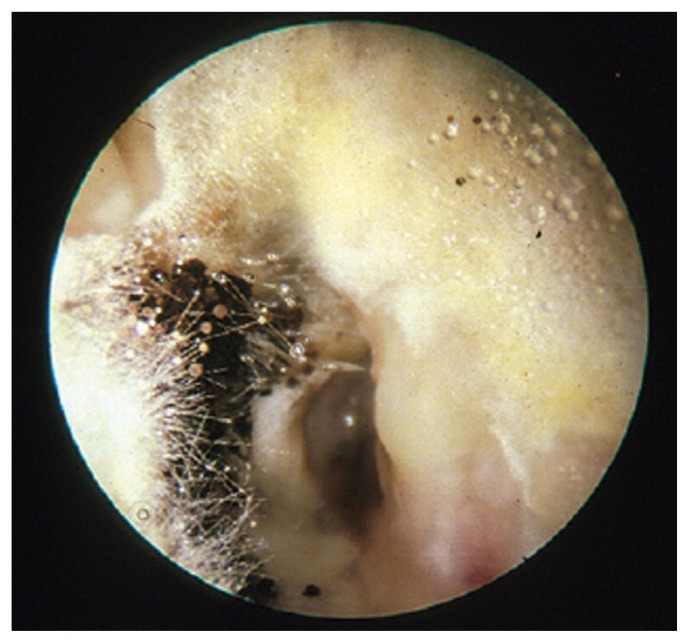

A comprehensive microbiological study in the United States indicated that fungi cause 1%–2% of AOE, with no significant geographical differences in proportion.40 The predominant fungal isolates from AOE are Candida and Aspergillus (Figure 3).38,40 Exposure to water, especially polluted water, and swimming are well-recognized risk factors for AOE.37,41 In one study, the most frequent predisposing factors for candidal otitis externa were swimming in public pools/baths and diabetes mellitus.42 Diagnosis is made by culture41 or perhaps by polymerase chain reaction assay.43 Uncomplicated cases may be treated with 2% acetic acid in propylene glycol or 1% clotrimazole solution.41

Figure 3.

Fungal otitis externa from Aspergillus niger. (Republished with permission of Royal College of General Practitioners, from Dannatt et al. Management of patients presenting with otorrhoea: diagnostic and treatment factors. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(607):e168–70.)

Fungi are occasionally the etiologic agents in malignant otitis externa. It is generally seen in diabetics or immunocompromised persons following prolonged antibiotic treatment for bacterial malignant otitis externa (without a reported link to freshwater exposure).44

Other Specific Infections Occasionally Linked to Freshwater

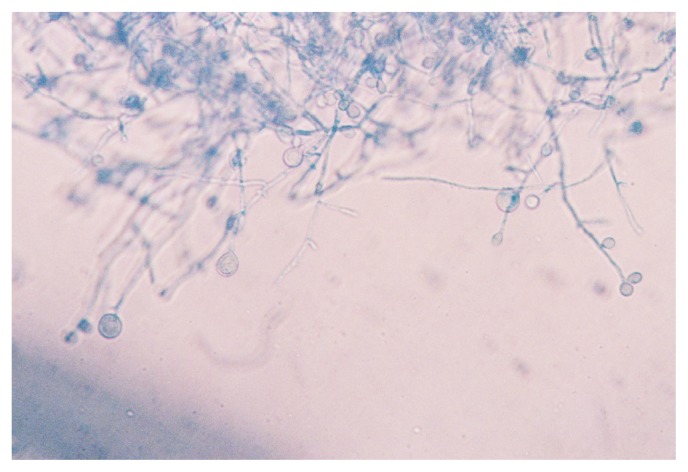

Several other specific diseases may rarely be caused by fungi of freshwater origin. These are typically documented as single case reports or small case series. Traumatic freshwater exposures following natural disasters, near-drowning episodes or significant aspiration may result in deep infections by fungi.3,45 These infections include deep soft tissue or bone infections, central nervous system infections (including meningitis and brain abscess) and pulmonary infections, generally occurring in immunocompetent hosts.45–49 Such infections are often delayed in onset, as compared to bacterial infections, following the traumatic episode.45 Causative agents include fungi in the family Mucoraceae, Cladophialophora, Fusarium, Aspergillus, Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium.28,45–48 The latter, while primarily found in soil, may be found in muddy water, sewage, and polluted, brackish and other freshwater.28,49 Scedosporium apiospermum (Figure 4) also may cause colonization and infection of the respiratory tract in persons with predisposing conditions, systemic invasive disease (usually in immunocompromised hosts) and keratitis, and has rarely been associated with otitis externa.28,50

Figure 4.

Lactophenol aniline blue-stained appearance of Scedosporium apiospermum grown on liquid media at 37°C, pH 7.2.

Common superficial fungal infections also may rarely result from freshwater exposure. Dermatophytes and other keratinophilic fungi have been reported in freshwater and sources of drinking water.13–15,51 The presence of these fungi in superficial waters does not necessarily equate with the level of pollution or contamination, as temperature and other natural properties of the bodies of water may promote their growth.51 These microorganisms also have been identified in public baths and swimming pools.4,52,53 However, freshwater exposure is an unusual cause of fungal infection of skin or nails, such as tinea pedis.4 Occasionally, epidemiologic evidence suggests an association between sources such as swimming pools and dermatophyte infections such as tinea pedis.53

Prevention

General measures for all persons to reduce the risk of freshwater-acquired fungal disease include community guidelines for the prevention and detection of waterborne fungal infection, issued in conjunction with prevention of bacterial and parasitic infections.5,10 Specific individual preventive measures include use of earplugs while swimming (and, in those with recurrent infection, gently rinsing the ear canals after swimming with equal portions of vinegar and rubbing alcohol) to prevent AOE,37 and washing feet thoroughly after public swimming or bathing.53

Additionally, one should ensure proper use of contact lenses (including therapeutic lenses) and contact lens solution (avoiding tap water),26 wash all wounds thoroughly and take care not to aspirate potentially contaminated freshwater. Special care for the immunocompromised may include enhanced monitoring of hospital water supplies, avoidance of hospital (and sometimes domestic) tap water and showers and rigorous handwashing by all patients and personnel.5,10

Conclusions

Potentially pathogenic fungal microorganisms are found in a variety of freshwater sources, including surface waters, drinking water and public bathing and swimming facilities. Fortunately, fungal infections as a result of freshwater exposure or trauma are rare. The most common entities appear to be fungal keratitis, otitis externa and tinea pedis. Well-documented reports describe deep fungal infections resulting from freshwater exposures following natural disasters or near-drowning episodes. As with most cryptic fungal infections, freshwater-related or otherwise, this etiology should be suspected when bacterial cultures or molecular tests are normal or when the infection inexplicably worsens or fails to resolve with appropriate antibacterial therapy.

Patient-Friendly Recap.

Infections caused by fungi from freshwater sources are uncommon but can prove harmful if undiagnosed or left untreated.

The author reviewed diseases caused by exposure to freshwater fungi, identifying potential risk factors and describing means of prevention such as use of ear plugs, thorough washing after swimming and storage of contact lenses in proper solution, not tap water.

Clinicians should suspect fungal causation when bacterial cultures or tests are normal or when the infection fails to resolve with appropriate antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the librarians of Aurora Health Care for retrieving many articles referenced in this review.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Note Added in Proof

For additional context, the reader is referred to the recent case report of a patient with disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection following kidney-liver transplantation, with possible transmission from a donor following near-drowning: Leek R, Aldag E, Nadeem I, et al. Scedosporiosis in a combined kidney and liver transplant recipient: a case report of possible transmission from a near-drowning donor. Case Rep Transplant. 2016; 2016:1879529.

References

- 1.Baumgardner DJ. Soil-related bacterial and fungal infections. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:734–44. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.110226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgardner DJ. Disease-causing fungi in homes and yards in the midwestern United States. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2016;3:99–110. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dworzack DL, Clark RB, Padgitt PJ. New causes of pneumonia, meningitis, and disseminated infections associated with immersion. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1987;1:615–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitlik S, Berger SA, Huminer D. Nonenteric infections acquired through contact with water. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:54–63. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anaissie EJ, Penzak SR, Dignani MC. The hospital water supply as a source of nosocomial infections: a plea for action. Arch Int Med. 2002;162:1483–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.13.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesquita-Rocha S, Godoy-Martinez PC, Gonçalves SS, et al. The water supply system as a potential source of fungal infection in paediatric haematopoietic stem cell units. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pielou EC. Fresh Water. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barton LL, Northrup DE. Microbial Ecology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 107–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandrin TR, Dowd SE, Herman DC, Maier RM. Aquatic environments. In: Maier RM, Pepper IL, Gerba CP, editors. Environmental Microbiology. Second Edition. Burlington, MA: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hageskal G, Lima N, Skaar I. The study of fungi in drinking water. Mycol Res. 2009;113:165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cateau E, Delafont V, Hechard Y, Rodier MH. Free-living amoebae: what part do they play in hospital-associated infections? J Hosp Infect. 2014;87:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barberán A, Ladau J, Leff JW, et al. Continental-scale distributions of dust-associated bacteria and fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5756–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420815112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdullah SK, Hassan DA. Isolation of dermatophytes and other keratinophilic fungi from surface sediments of the Shatt Al-Arab River and its creeks at Basrah, Iraq. Mycoses. 1995;38:163–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1995.tb00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiziewicz B, Czeczuga B. Occurrence of keratinophilic fungus Lagenidium humanum Karling in the surface waters of Podlasie. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst. 2002;47:194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulfig K, Plaza G, Terakowski M, Staszewski T. A study of keratinolytic fungi in mountain sediments. I. Hair-baiting data. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 1998;49:469–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Bahry SN, Elshafie AE, Mahmoud IY, Al-Hinai JA. Opportunistic pathogens relative to physiochemical factors in water storage tanks. J Water Health. 2011;9:382–93. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community water treatment. [Accessed Feb. 16, 2016]. http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/drinking/public/water_treatment.html.

- 18.Ashbolt NJ. Microbial contamination of drinking water and human health from community water systems. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2:95–106. doi: 10.1007/s40572-014-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubka V. Chaetomium. In: Russell R, Paterson M, Lima N, editors. Molecular Biology of Food and Water Borne Mycotoxigenic and Mycotic Fungi. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2015. p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonçalves AB, Paterson RRM, Lima N. Survey and significance of filamentous fungi from tap water. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2006;209:257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hageskal G, Knutsen AK, Gaustad P, de Hoog GS, Skaar I. Diversity and significance of mold species in Norwegian drinking water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7586–93. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01628-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warris A, Gaustad P, Meis JF, Voss A, Verweij PE, Abrahamsen TG. Recovery of filamentous fungi from water in a paediatric bone marrow transplantation unit. J Hosp Infect. 2001;47:143–8. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Wielen PWJJ, van der Kooij D. Nontuberculous mycobacteria, fungi, and opportunistic pathogens in unchlorinated drinking water in the Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:825–34. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02748-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raad I, Tarrand J, Hanna H, et al. Epidemiology, molecular mycology, and environmental sources of Fusarium infection in patients with cancer. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:532–7. doi: 10.1086/502102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javey G, Zuravleff JJ, Yu VL. Fungal infections of the eye. In: Anaissie EJ, McGinnis MR, Pfaller MA, editors. Clinical Mycology. Second Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 623–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kredics L, Narendran V, Shobana CS, et al. Filamentous fungal infections of the cornea: a global overview of epidemiology and drug sensitivity. Mycoses. 2015;58:243–60. doi: 10.1111/myc.12306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritterband DC, Seedor JA, Shah MK, Koplin RS, McCormick SA. Fungal keratitis at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary. Cornea. 2006;25:264–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000177423.77648.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:157–97. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yildiz EH, Abdalla YF, Elsahn AF, et al. Update on fungal keratitis from 1999 to 2008. Cornea. 2010;29:1406–11. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181da571b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang DC, Grant GB, O’Donnell K, et al. Multistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution. JAMA. 2006;296:953–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Short DP, O’Donnell K, Geiser DM. Clonality, recombination, and hybridization in the plumbing-inhabited human pathogen Fusarium keratoplasticum inferred from multilocus sequence typing. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg P. Microsporidia infection of the cornea – a unique and challenging disease. Cornea. 2013;32(Suppl 1):S33–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182a2c91f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramanan P, Pritt BS. Extraintestinal microsporidiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3839–44. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00971-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan J, Lee P, Lai Y, et al. Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis after rugby tournament, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1484–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1909.121464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendes MO, Moraes MA, Renoiner EI, et al. Acute conjunctivitis with episcleritis and anterior uveitis linked to adiaspiromycosis and freshwater sponges, Amazon region, Brazil, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:633–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.081282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vilela RC, Vilela L, Vilela P, et al. Etiologic agents of fungal endophthalmitis: diagnosis and management. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:707–21. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9854-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beers SL, Abramo TJ. Otitis externa review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:250–6. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000121246.99242.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pontes ZB, Silva AD, Lima Ede O, et al. Otomycosis: a retrospective study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:367–70. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942009000300010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurnatowski P, Filipiak J. Otitis externa: the analysis of relationship between particular signs/symptoms and species and genera of identified microorganisms. Wiad Parazytol. 2008;54:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1166–77. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vennewald I, Klemm E. Otomycosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorko E, Jenca A, Orencák M, Virágová S, Pilipcinec E. Otomycosis of candidal origin in eastern Slovakia. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2004;49:601–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02931541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gruber M, Roitman A, Doweck I, et al. Clinical utility of a polymerase chain reaction assay in culture-negative necrotizing otitis externa. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:733–6. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamzany Y, Soudry E, Preis M, et al. Fungal malignant external otitis. J Infect. 2011;62:226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diaz JH. Superficial and invasive infections following flooding disasters. Am J Disaster Med. 2014;9:171–81. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2014.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leroy P, Smismans A, Seute T. Invasive pulmonary and central nervous system aspergillosis after near-drowning of the child: case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e509–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimizu J, Yoshimto M, Takebayashi T, Ida K, Tanimoto K, Yamashita T. Atypical fungal vertebral osteomyelitis in a tsunami survivor of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E739–42. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen SC, Blyth CC, Sorrell TC, Slavin MA. Pneumonia and lung infections due to emerging and unusual fungal pathogens. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2011;32:703–16. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rainer J, De Hoog GS. Molecular taxonomy and ecology of Pseudallescheria, Petriella and Scedosporium prolificans (Microascaceae) containing opportunistic agents on humans. Mycol Res. 2006;110:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guarro J, Kantarcioglu AS, Horré R, et al. Scedosporium apiospermum: changing clinical spectrum of a therapyrefractory opportunist. Med Mycol. 2006;44:295–327. doi: 10.1080/13693780600752507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulfig K. The occurrence of keratinolytic fungi in waste and waste-contaminated habitats. In: Kushwaha RKS, Guarro J, editors. Biology of Dermatophytes and other Keratinophilic Fungi. Bilbao, Spain: Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia; 2000. pp. 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brandi G, Sisti M, Paparini A, et al. Swimming pools and fungi: an environmental epidemiology survey in Italian indoor swimming facilities. Int J Environ Health Res. 2007;17:197–206. doi: 10.1080/09603120701254862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamihama T, Kimura T, Hosokawa JI, Ueji M, Takase T, Tagami K. Tinea pedis outbreak in swimming pools in Japan. Public Health. 1997;111:249–53. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(97)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]