Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize the reported risk prediction models and identify the most prevalent factors for incident delirium in older inpatient populations (age ≥ 65 years). In the future, these risk factors could be used to develop a delirium risk prediction model in the electronic health record that can be used by the Hospital Elder Life Program to reduce the incidence of delirium.

Methods

A medical librarian customized and conducted a search strategy for all published articles on delirium prediction models using an array of electronic databases and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, a geriatrician and two research associates assessed the quality of the selected studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Results

A total of 4,351 articles were identified from initial literature search. After review, data were extracted from 12 studies. The quality of these studies was assessed using NOS and ranged from 4 to 8. The most common risk factors reported were dementia, decreased functional status, high blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio, infection and severe illness.

Conclusions

The most prevalent factors associated with incidence of delirium in hospitalized older patients identified by this systematic review could be used to develop an electronic health record-generated risk prediction model to identify inpatients at risk of developing delirium.

Keywords: incidence, delirium, Hospital Elder Life Program, inpatient, hospitalized older adults, cognitive impairment, altered mental status, risk factors

Delirium is an acute cognitive impairment in patients 65 years of age or older. It is common in hospitalized older adults and reports of incidence range from 15% to 50%. Delirium is one of the most serious, common and fatal complications during hospitalization, and scientists have not yet properly discerned its pathophysiology.1 Prevention is the most effective strategy, with up to 40% of delirium cases deemed preventable.1,2

The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), a multicomponent evidence-based program to reduce incidence of delirium,3 has been successfully implemented in more than 200 hospitals across the United States and 11 more around the world.4 HELP has proved to be cost-effective in decreasing the incidence of delirium and cognitive decline. The program’s interventional strategy includes therapeutic activities, reorientation, nonpharmacological sleep protocol, reduced usage of psychoactive medications and maintenance of adequate hydration and nutrition.3 If clinicians could identify patients at higher risk of developing delirium using factors noted in the electronic health record (EHR), HELP measures could be applied to these individuals, effectively reducing incidence in older patients.

The purpose of this systematic review was to summarize the reported risk prediction models and identify the most prevalent factors for incident delirium in older inpatient populations (age ≥ 65 years), with the ultimate goal of developing a delirium risk prediction model in the EHR that can be used within the HELP framework to reduce the incidence of delirium.

METHODS

Search Strategy

A medical librarian customized and conducted the search strategy for all published medical articles on delirium prediction models. The electronic databases Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE and PsycINFO were searched using PICO-based inquiries, which include patient problem or population, intervention, comparison and outcomes (Table 1). Controlled vocabulary terms specific to database as well as relevant keywords were used, including variants of delirium, altered mental status, acute confusional state, acute brain syndrome, acute brain failure, metabolic encephalopathy, predict, predictive, prediction, models, modeling, scores, scoring, tests, testing, rules, index and indices. The bibliographies of included studies were examined, and no additional articles were referenced (Online Appendix 1).

Table 1.

PICO Questions

| Population | Older adult patients admitted to a medical service |

| Intervention | Risk prediction models derived and validated in a cohort of medical inpatients |

| Comparator | Studies comparing two or more risk prediction models in a population will be included |

| Outcomes | Incidence delirium |

| Timings | Any time during hospital stay |

| Settings | Exclude disease-specific, non-English, postsurgical and intensive care studies |

Inclusion criteria were: original research articles; non-disease-specific delirium in older patients admitted to the medical ward; patients older than 65 years; and acute medical inpatient population. Exclusion criteria were: review articles, reports, commentary, abstracts and presentations, disease-specific delirium, intensive care unit studies, and studies that included surgical cases.

Relevance and Quality Assessment

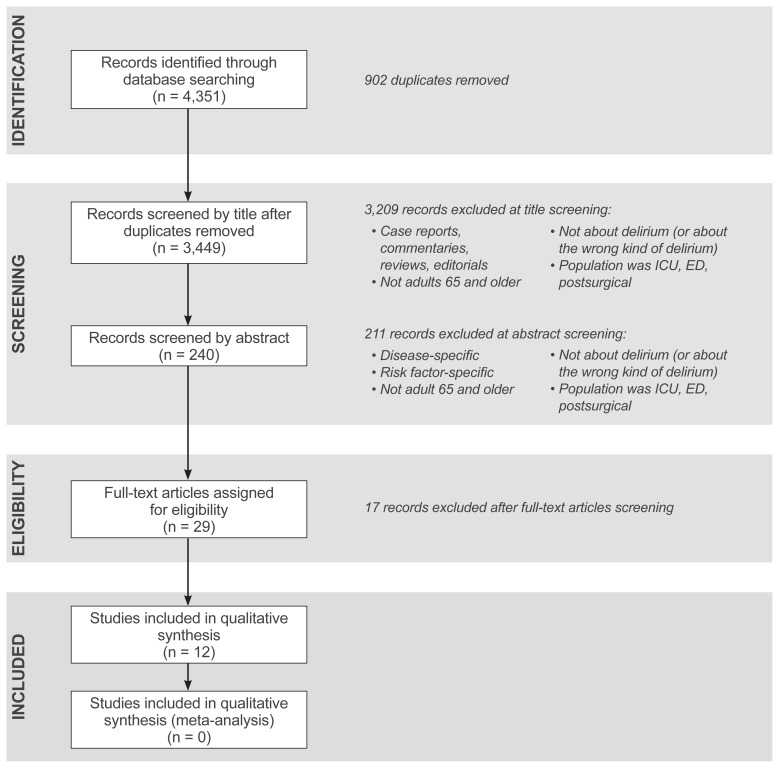

A total of 4,351 articles were identified by literature search. After removing duplicates, 3,449 articles remained. Abstracts from these articles were further reviewed for elimination based on inclusion/exclusion criteria using PRISMA guidelines5 (Figure 1). After this round of elimination, a total of 29 articles were further screened for relevance to the topic by three reviewers (authors AK, SK and WA) (Table 2). The criteria for relevance included: English language studies, older population, primary studies that develop prediction models of delirium risk, and having derivation and/ or validation cohorts. We excluded systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Using these criteria for relevance, 12 articles were included in the final systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Criteria for Relevance of Full-Text Articles

| 1. Is the full text of the article in English? | |

| Yes | Proceed to #2 |

| No | Code X1, STOP |

| 2. Does the study population include older adult patients admitted to a medical service? | |

| Yes | Proceed to #3 |

| No | Code X2, STOP |

| 3. Is the article a primary study that develops or tests prediction models for risk of delirium? | |

| Yes | Proceed to #4 |

| No | Code X3, proceed to # 5 |

| 4. Is this model tested in both a derivation and validation cohort, or is it a validation of a previously developed model? | |

| Yes | Code I4, proceed to #6 |

| No | Code X4, proceed to #6 |

| 5. Is the article a systematic review or meta-analysis of prediction models for delirium? | |

| Yes | Code X5, proceed to #6 |

| No | Proceed to # 6 |

| 6. If article meets none of the above criteria but may be useful for background/discussion, add code B. | |

The quality of the 12 studies was assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) project.6 The purpose of the NOS tool is to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies to be used in a systematic review. Its “star system” assesses studies on three major criteria: selection, comparability of the groups, and study-type outcome (cohort) vs exposure (case-control) study design. The NOS ranges from 1 to 9, with 1 being poor and 9 being excellent (Table 3).6

Table 3.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale6 for Quality Assessment of Cohort Studies on Incident Delirium

| Selection (max: 4 stars) |

1) Representativeness of the exposed cohort

|

2) Selection of the nonexposed cohort

|

3) Ascertainment of exposure

|

4) Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study

|

| Comparability (max: 2 stars) |

1) Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis

|

| Outcome (max: 3 stars) |

1) Assessment of outcome

|

2) Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur

|

3) Was there adequacy of follow-up of cohorts

|

The scoring for quality ranges from 1 to 9 stars, with 1 star indicating poor quality and 9 stars indicating highest quality. A study may be awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the Selection and Outcome categories. A maximum of two stars may be given for Comparability.

Asterisks (*) represent high-quality criteria.

The following parameters were used in the final review of the articles: study description, study population, delirium assessment method, incidence of delirium, and risk factors for delirium. Whenever there was disagreement, the group of three article reviewers made the decision by mutual consensus.

RESULTS

The overall incidence of delirium in the 12 analyzed studies ranged from 4% to 26%. A total of 20 risk factors were identified (Table 4).7–18 The quality of the studies ranged from 4 to 8 (Table 5). The most common issues leading to lower quality scores were lack of documentation of follow-up and blinding.

Table 4.

Summary of Risk Factors for Delirium*

| Risk factor | Inouye (1993)7 | Pompei (1994)8 | Inouye (1996)9 | O’Keeffe (1996)10 | Inouye (1999)11 | Wakefield (2002)12 | Isfandiaty (2012)13 | Martinez (2012)14 | Carrasco (2014)15 | Kobayashi (2013)16 | Rudolph (2015)17 | Pendlebury (2016)†18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive impairment | RR: 2.8 (1.2–6.7) | Adj. OR: 2.14 (1.12–4.12) | – | Adj. OR: 4.7 (1.4–15.2) | – | OR: 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | Adj. HR: 3.12 (1.89–5.13) | – | − OR: 1.86 (1.06–3.28) | OR: 6.3 (2.9–13.7) | X | |

| Severe illness | RR: 3.5 (1.5–8.2) | – | – | Adj. OR: 5.6 (1.7–18.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 3.5 (1.5–8.2) | X |

| Vision impairment | Adj. RR: 3.5 (1.2–10.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 1.57 (1–2.8) | – |

| Comorbidity | – | Adj. OR: 1.68 (1.37–2.07) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Depression | – | Adj. OR: 3.19 (1.65–6.17) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alcoholism | – | Adj. OR: 5.66 (2.07–15.48) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 5.47 (2.02–14.79) | – | – |

| Decreased functional status | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 8.4 (1.1–62.1) | Adj. HR: 1.74 (1.07–2.82) | β: 1.397 (SE: 0.350) | Barthel index: 0.037 (SE: 0.010) | OR: 5.81 (3.16–10.69) | – | X |

| Physical restraints | – | – | RR: 4.4 (2.5–7.9) | – | Adj. RR: 4.4 (2.5–7.9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Malnutrition | – | – | RR: 4 (2.2–7.4) | – | Adj. RR: 4 (2.2–7.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| >3 new medications added | – | – | RR: 2.9 (1.6–5.4) | – | Adj. RR: 2.9 (1.6–5.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Iatrogenic event | – | – | RR: 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | – | Adj. RR: 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Presence of bladder catheter | – | – | RR: 2.4 (1.2–4.7) | – | Adj. RR: 2.4 (1.2–4.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Previous or current smoker | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 0.2 (0.03–1.1) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Infection | – | – | – | – | – | – | Without sepsis Adj. HR: 1.83 (0.82–4.10) With sepsis Adj. HR: 4.86 (2.14–11.04) |

– | – | – | OR: 3 (1.4–6.1) | – |

| Abnormal lab | Renal‡ RR: 2 (0.9–4.6) | – | – | Renal‡ Adj. OR: 5.1 (1.7–14.9) | – | Sodium OR: 11.1 (1.7–74.5) Albium OR: 10.7 (1.5–74.7) |

– | – | Renal‡ β: 0.053 (SE: 0.019) | – | – | – |

| Psychotropic medication at admission | – | – | – | – | – | – | β: 1.515 (SE: 0.443) | – | – | – | – | |

| Malignancy | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 2.34 (1.61–3.41) | – | – |

| History of delirium | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 14.35 (8.41–24.47) | – | – |

| Fracture | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | OR: 6.6 (2.2–19.3) | – |

| Age | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | >84 years β: 1.381 (SE: 0.349) | – | – | >64 years OR: 3 (1.2–7.7) >79 years OR: 5.2 (2.6–10.4) |

X |

All values in parenthesis refer to 95% confidence interval unless otherwise noted.

Odds ratios not available for Pendlebury study.

Renal refers to disturbances in blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio.

Adj., adjusted; β, beta coefficient; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; SE, standard error.

Table 5.

Summary of Included Studies

| Study, year | Study description | Population (n) | Quality | Delirium assessment method | Incidence of delirium, n (%) | Risk factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Derivation cohort | Validation cohort | ||||||

| Kobayashi, 2013 | Retrospective cohort study at community hospital in Japan | Total: 3,570 DC: 2,400 VC: 1,170 |

5 (interview and follow-up) | DSM IV | 142 (4%) | 91 (3.8%, CI: 3.1%–4.6%) CHAID AUC: 0.82 Logistic: 0.78 |

51 (4.4%, CI: 3.3%–5.7%) CHAID AUC: 0.82 Logistic: 0.79 |

Based on CHAID method: history of delirium, underlying malignancy, activities of daily living Based on logistic regression method: history of delirium, underlying malignancy, functional impairment, alcohol, dementia |

| Inouye, 1996 | Two prospective cohort studies in tandem in a university hospital | 508 DC: 196 VC: 312 |

6 (control and follow-up) | CAM | 82 (16%) | 35 (18%) | 47 (15%) | Physical restraints, malnutrition, more than 3 new medications added, presence of bladder catheter, any iatrogenic event |

| Inouye, 1999 | Prospective cohort study | Total: DC: 107 VC: 174 |

6 (control and follow-up) | CAM | 25% | 27 (25%) | 174 (17%) | Physical restraints, malnutrition, more than 3 new medications added, presence of bladder catheter, any iatrogenic event |

| O’Keeffe, 1996 | Prospective study | Total: 225 DC: 125 VC: 100 |

6 (no trained researchers documented and follow-up) | DAS MMSE Physical exam |

53/184 (28.8%) | 28/100 (28%) AUC: 0.79 (Cl: 0.69–0.90) |

25/84 (30%) AUC: 0.75 (Cl: 0.63–0.86) |

History of chronic cognitive impairment, severe illness, urea/Cr disturbance, abnormal sodium level |

| Rudolph, 2015 | Retrospective analysis followed by prospective validation | Retrospective: 27,625 > 65 years old Prospective: 246 > 55 years old |

4 (only veterans population, control, no researcher, follow-up) | Retrospective: Electronic medical records Prospective: Patient interview + DSM IV |

Retrospective: 2,343 (8%) Prospective: 64 (26%) |

NA | Retrospective: 0.81 (Cl: 0.80–0.82) Prospective: 0.69 (Cl: 0.61–0.77) |

Impaired baseline cognition, vision impairment, severity of illness, infections, fracture, age |

| Pendlebury, 2016 | Prospective observational cohort study, U.K. | 308 | 6 (researchers did not do the assessment, prevalence included, follow-up) | CAM DSM IV MMSE AMTS |

28 (9.09%) | NA | 0.73 to 0.83 | Old age, severe illness defined by SIRS ≥ 2, cognitive impairment, functional dependency |

| Isfandiaty, 2012 | Retrospective cohort study, Indonesia | 457 | 5 (study control, researchers did not assess for delirium, follow-up) | Diagnosis made by treating physicians. Presence of acute mental change in previously fully alert patients marked by disorientation, agitation, sleep disturbance |

87 (19%) AUC: 0.82 (CI: 0.78–0.88) |

NA | NA | Infection with or without sepsis, decreased functional status |

| Inouye, 1993 | Two prospective cohort studies | Total 281 DC: 107 VC: 174 |

8 (follow-up no statement) | CAM | 56 (19.92%) | 27 (25.2%) AUC: 0.74 (Cl: 0.63–0.85) |

29 (16.66%) | Vision impairment, severe illness, cognitive impairment, urea/Cr disturbance |

| Carrasco, 2013 | Observational prospective cohort, Chile | Total: 478 DC: 374 VC: 104 |

5 (no controls, assessed by geropsych, follow-up) | CAM | 37 (7.74%) | 25 (6.68) | 12 (11.53) AUC: 0.78 (CI: 0.66–0.90) |

Barthel index, urea/Cr disturbance |

| Wakefield, 2002 | Prospective cohort study | 117 | 3 (no documentation of follow-up and blinding) | NEECHAM confusion scale | 14% | NA | NA | Cognitive impairment, admitted from other than home, functional status, abnormal labs, infection |

| Pompei, 1994 | Two prospective cohort studies | DC: 432 VC: 323 |

6 | DSM-III-R | NA | 15% | 26% | Comorbidity, depression, alcoholism, functional status |

| Martinez, 2012 | Prospective cohort study, Spain | 397 | 5 (no documentation of follow-up) | CAM | NA | 13% | 25% AUC: 0.85 |

Function, age, psychotropic medications at admission |

AMTS, abbreviated mental test score; AUC, area under curve; CAM, confusion assessment method; CHAID, chi-squared automatic interaction detector; CI, 95% confidence interval; Cr, creatinine; DAS, Delirium Assessment Scale; DC, derivation cohort; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; NA, not available; VC, validation cohort.

Three studies were done retrospectively. Nine were prospective. Six studies were done in the United States. Two of the studies were external validation studies (Pendlebury et al and Rudolph et al). Overall, each study was able to identify 2–6 risk factors for delirium. The most commonly reported risk factors for delirium were dementia, decreased functional status, high blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio, infection and severe illness. Other less common variables were alcohol, malignancy, history of delirium, older age, medications, physical restraints, malnutrition, admission from other than home and an iatrogenic event.

Cognitive impairment was the most commonly identified risk factor (noted in eight studies). Each study may have a different test performed to assess for cognition, including Folstein’s Mini-Mental State Examination, Blessed test and retrospective review.

Functional status was the second most common risk factor identified. The test used to measure functional status varied from study to study and included Functional Independence Measure, Barthel index, Katz activities of daily living and retrospective chart review.

DISCUSSION

Strengths and Limitations

In our systematic review, we studied 12 fair- to good-quality articles (as determined by NOS criteria) and were able to identify the most common risk factors of developing delirium in the inpatient setting, namely dementia, decreased functional status, high blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio, infection and severe illness.

We acknowledge a number of limitations in this systematic review. First, there was variation in the assessment of delirium among the original studies, with assessment performed by differing methods and personnel. Second, all the studies lacked follow-up data, one of the quality measures on NOS, thus lowering the quality scores for each study. Third, the incidence of delirium varied among the retrospective and prospective studies. Retrospective chart review may not be accurate for diagnosis of delirium and can miss the diagnosis of delirium in some cases.19

Despite these limitations, this review has strengths. Although the large number of predictors from a relatively small sample of studies –– 20 risk factors from 12 studies –– might seem concerning, our systematic review is consistent with previous research in identifying multiple factors for delirium. Delirium has a multifactorial etiology and is unlikely to be caused by a single factor. In fact, multiple causes may be responsible in most cases. Additionally, it is known that factors can jointly predispose to delirium depending on individual vulnerability.20

Future Direction

In the future, we intend to use this systematic review to develop a delirium predictive tool that can be generated automatically from the EHR. This will enable current delirium prevention programs to focus their efforts on patients who have the risk factors of developing delirium. Our health system has successfully leveraged the EHR to identify vulnerable older adults in a time-efficient manner. Specifically, a “delirium marker” has been developed within our system to aid in the identification of delirium prevalence within inpatient units.21 The delirium marker was derived from variables noted on the Acute Care for the Elders (ACE) Tracker. The ACE Tracker is an innovative, clinical decision support tool focused on older patients that is generated automatically on a daily basis from the EHR. This tool has been established for use in all the hospitals throughout our health system, and has been disseminated to five other health systems. The variables noted on the ACE Tracker are programmed from the EHR to identify high-risk patients.

We were prompted to undertake this systematic review due to some limitations in the EHR data as well as the recognition that the known risk factors for HELP may not be best in predicting delirium via the EHR. First, there is a lack of presence of some known predictors in the EHR record. Second, EHR data are entered by staff nurses while taking care of the patient; it is not research data. Last, there may be missing data. The success of delirium predictive tools in routine clinical practice has not been established but appears promising.22

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review summarizes the most frequently reported risk factors for delirium in hospitalized older patients. This collective information should be used to develop an electronic health record-generated delirium risk prediction model that can identify patients who are at risk of developing delirium, allowing for the application of preventive interventions and thereby reducing the incidence of delirium.

Patient-Friendly Recap.

Delirium is a mental impairment common in older adults, especially those hospitalized. Myriad patient factors contribute to the likelihood of a patient developing delirium.

The authors reviewed past reports of delirium incidence to determine the most common risk factors and possibly assist the creation of a clinically useful risk prediction tool, driven by the electronic health record.

The most common risk factors associated with delirium are presence of dementia, decreased functional ability, abnormal blood test result (ie, high blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio), infection and severe illness.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383:911–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43:326–33. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM., Jr The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hospital Elder Life Program. HELP sites. [Accessed August 11, 2016]. http://www.hospitalelderlifeprogram.org/about/help-sites/

- 5.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Coding manual and scale. [Accessed August 1, 2016]. available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 7.Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Hurst LD, Tinetti ME. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:474–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pompei P, Foreman M, Rudberg MA, Inouye SK, Braund V, Cassel CK. Delirium in hospitalized older persons: outcomes and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:809–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275:852–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530350034031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Keeffe ST, Lavan JN. Predicting delirium in elderly patients: development and validation of a risk-stratification model. Age Ageing. 1996;25:317–21. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inouye SK. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:393–400. doi: 10.1159/000017177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakefield BJ. Risk for acute confusion on hospital admission. Clin Nurs Res. 2002;11:153–72. doi: 10.1177/105477380201100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isfandiaty R, Harimurti K, Setiati S, Roosheroe AG. Incidence and predictors for delirium in hospitalized elderly patients: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Med Indones. 2012;44:290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez JA, Belastegui A, Basabe I, et al. Derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for delirium in patients admitted to a medical ward: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001599. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrasco MP, Villarroel L, Andrade M, Calderόn J, González M. Development and validation of a delirium predictive score in older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:346–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi D, Takahashi O, Arioka H, Koga S, Fukui T. A prediction rule for the development of delirium among patients in medical wards: Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) decision tree analysis model. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:957–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudolph JL, Doherty K, Kelly B, Driver JA, Archambault E. Validation of a delirium risk assessment using electronic medical record information. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pendlebury ST, Lovett N, Smith SC, Cornish E, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Delirium risk stratification in consecutive unselected admissions to acute medicine: validation of externally derived risk scores. Age Ageing. 2016;45:60–5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saczynski JS, Kosar CM, Xu G, et al. A tale of two methods: chart and interview methods for identifying delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:518–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malone ML, Vollbrecht M, Stephenson J, Burke L, Pagel P, Goodwin JS. Acute Care for Elders (ACE) tracker and e-Geriatrician: methods to disseminate ACE concepts to hospitals with no geriatricians on staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:161–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqi N. Predicting delirium: time to use delirium risk scores in routine practice? Age Ageing. 2016;45:9–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.