Abstract

This study analyzes trends in physicians’ recommendations for cough and cold medicine for children in the United States between 2002 and 2015.

Respiratory infections are extremely common pediatric illnesses, and families frequently treat children with cough and cold medicines (CCM). In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that children younger than 2 years not use over-the-counter (OTC) CCM given concerns about efficacy and safety.1 Soon thereafter, manufacturers voluntarily relabeled CCM for children 4 years and older,1 and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended avoiding CCM in children younger than 6 years. Subsequent national US utilization studies through 2010 showed equivocal effects on pediatric CCM use.2,3 We studied trends over a broader timeframe in physicians’ recommendations for CCM and, for comparison, antihistamines in the US pediatric population.

Methods

This study was determined to be non–human subjects research by the Rutgers institutional review board, which did not require consent for use of fully deidentified data. We used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (2002-2015) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (2002-2015, outpatient and emergency department), nationally representative surveys of US office-based and hospital-based ambulatory settings, respectively. These yearly surveys contain cross-sectional, visit-level data on demographics, diagnoses, and medications ordered or provided at visits including recommended OTC medications. The study sample consisted of all visits for children younger than 18 years.

We measured all visits with recommendations for CCM (drugs containing antitussives, decongestants, or expectorants), subclassified by the presence of opioid ingredients (codeine or hydrocodone). We included codeine monotherapy for visits with respiratory diagnoses. Separately, we also studied single-agent antihistamines for acute respiratory infections. Single-agent antipyretics were excluded.

We conducted logistic regression analyses, with elapsed time ([Survey Year−2002]/14) as the independent variable, adjusting for covariates (Table). We examined age-specific temporal changes via a 3-way interaction between trend, era (2002-2008 vs 2009-2015), and age group. All analyses incorporated visit weights, clustering, and strata for the complex survey design. Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Table. Physicians' Recommendations of CCM and Antihistamines by Age Group and Era.

| Age, y | 2002-2008 | 2009-2015 | 2009-2015 vs 2002-2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate (95% CI)a | No. | Rate (95% CI)a | aOR (95% CI)b | P Value | |

| Nonopioid CCM | ||||||

| <2 | 649 | 26.1 (21.0-32.5) | 223 | 11.6 (9.0-15.1) | 0.3 (0.1-1.01) | .05 |

| 2-3 | 548 | 41.9 (33.8-49.8) | 298 | 30.2 (23.7-38.3) | 1.04 (0.2-4.9) | .96 |

| 4-5 | 392 | 39.6 (32.8-47.7) | 316 | 37.0 (30.2-45.2) | 1.3 (0.3-5.9) | .70 |

| 6-11 | 764 | 36.8 (31.1-43.4) | 547 | 28.0 (23.6-33.3) | 0.9 (0.2-3.7) | .84 |

| 12-17 | 617 | 26.5 (21.6-32.5) | 490 | 22.1 (18.3-26.5) | 0.7 (0.2-2.9) | .59 |

| Opioid CCM | ||||||

| <4c | 124 | 3.8 (2.6-5.6) | 31 | 0.7 (0.4-1.3) | 0.1 (0.005-1.02) | .05 |

| 4-5 | 68 | 6.7 (3.9-11.8) | 36 | 4.0 (2.1-7.6) | 0.1 (0.002-1.9) | .11 |

| 6-11 | 151 | 6.7 (4.9-9.1) | 83 | 3.1 (2.0-4.7) | 0.4 (0.03-4.6) | .42 |

| 12-17 | 137 | 4.7 (3.3-6.5) | 104 | 3.6 (2.5-5.1) | 1.2 (0.1-16.4) | .90 |

| Single-agent antihistamines | ||||||

| <2 | 314 | 7.2 (5.5-9.4) | 271 | 10.9 (8.4-14.3) | 10.6 (2.0-55.4) | .005 |

| 2-3 | 260 | 17.1 (13.4-21.7) | 227 | 20.3 (16.0-25.8) | 10.3 (1.4-74.9) | .02 |

| 4-5 | 219 | 17.3 (13.6-21.9) | 199 | 19.2 (14.8-24.9) | 5.6 (0.8-44.9) | .10 |

| 6-11 | 317 | 11.9 (9.1-15.4) | 322 | 14.3 (10.4-19.5) | 11.1 (1.2-100.9) | .03 |

| 12-17 | 247 | 8.9 (6.9-11.5) | 214 | 9.8 (7.3-13.1) | 4.0 (0.5-35.1) | .21 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CCM, cough and cold medicine.

Prevalence rates expressed as recommendations per 1000 pediatric visits.

Models compared trends of recommendations in 2009-2015 with trends in 2002-2008 within each age group, adjusted for sex, insurance (private, public, other), race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, or other), setting (ambulatory clinic, hospital-based outpatient clinic, or emergency department), and region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West).

The 2 youngest age groups were combined for analyses of opioid CCM to avoid cell sizes less than 30, which yield unreliable estimates.

Results

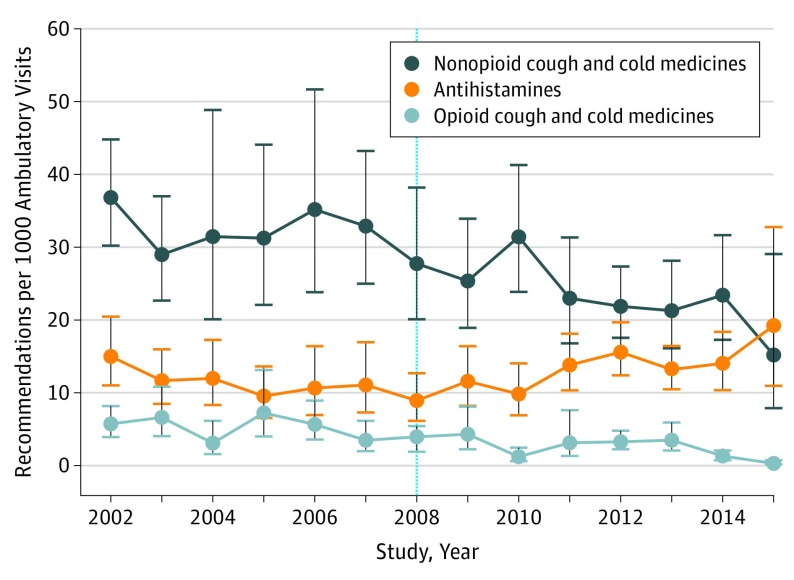

In a sample representing 3.1 billion pediatric visits over 14 years, US physicians ordered approximately 95.7 million CCM, of which 12.0% (sample n = 734 of 5525; 95% CI, 10.0%-14.3%) contained opioids. Recommendations for opioid-containing and nonopioid CCM declined substantially, while recommendations for antihistamines rose (Figure). After 2008, compared with older children, the trend in recommendations for nonopioid CCM appeared to decline more strongly among children younger than 2 years and among children younger than 6 years for opioid-containing CCM (Table). The trend in recommendations for antihistamines increased overall and appeared strongest in children younger than 12 years (Table). Sensitivity analyses moving the analytic cut point 1 year later did not substantively change the results (data not shown).

Figure. Trends in Physicians’ Recommendations of Nonopioid Cough and Cold Medicines (CCM), Opioid CCM, and Antihistamines for Children (2002-2015).

Opioid-containing CCM included codeine monotherapy when prescribed during visits for respiratory conditions. Antihistamine recommendations were limited to visits for acute respiratory infections. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Dotted line indicates the year of the public health advisory and labeling changes for pediatric CCM use.

Discussion

Experts have long questioned the safety and effectiveness of CCM in children; a 2018 review of the evidence4 validates these concerns. Our findings suggest that physicians’ recommendations of these medicines have steadily declined in the United States since 2002. These declines appeared to accelerate in children younger than 2 years after the FDA’s 2008 public health advisory, with possible replacement by increasing recommendations of offlabel antihistamines. Notably, prescriptions for opioid-containing CCM were declining before the FDA’s 2018 recommendations that all children avoid them5; these declines may have accelerated in young children after 2008. However, trends in recommendations of nonopioid CCM for children ages 2 to 6 years did not change after 2008 despite changes in labeling and the American Academy of Pediatrics’ efforts to limit such use.

Our findings are consistent with reported decreases in unintentional pediatric CCM ingestions and associated adverse events after 2008.6 Others suggested declines in CCM prescribed to children younger than 2 years but used a pre/post design without accounting for secular trends.3 Our results also contrast with prior work showing no decreases in recommendations of OTC CCM for children younger than 2 years after 20083 or in cough-associated codeine prescribing in emergency departments after 2006 professional society guidelines.2 Our study was limited by imprecision in age-specific estimates and our inability to assess actual use of CCM and antihistamines, including unfilled prescriptions and OTC drugs not recommended by physicians. Future work should investigate more recent trends in CCM use and related outcomes in pediatric populations.

References

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Use caution when giving cough and cold products to kids. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/SpecialFeatures/ucm263948.htm. Published 2018. Accessed November 13, 2018.

- 2.Kaiser SV, Asteria-Penaloza R, Vittinghoff E, Rosenbluth G, Cabana MD, Bardach NS. National patterns of codeine prescriptions for children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1139-e1147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Rasooly I, Brooks G, Pines J, May L, van den Anker J. The impact of pediatric labeling changes on prescribing patterns of cough and cold medications. J Pediatr. 2014;165(5):1024-8.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Driel ML, Scheire S, Deckx L, Gevaert P, De Sutter A. What treatments are effective for common cold in adults and children? BMJ. 2018;363:k3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration FDA drug safety communication: FDA requires labeling changes for prescription opioid cough and cold medicines to limit their use to adults 18 years and older. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm590435.htm. Published 2018. Accessed November 13, 2018.

- 6.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Reid N, van den Anker J, Litovitz T. Effect of cough and cold medication restriction and label changes on pediatric ingestions reported to United States poison centers. J Pediatr. 2013;163(5):1372-1376. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]