Abstract

This cross-sectional study assesses the growth in the number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses vs randomized clinical trials from 1995 to 2017.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRMAs) and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are considered the most robust and reliable forms of evidence to guide clinical practice. Previous research has demonstrated year-over-year increases in the number of published RCTs between 1950 and 20071 as well as increases in the number of published SRMAs through 2016.2,3 The increase in SRMAs is needed to update cumulative evidence,2 although some investigators speculate that SRMAs may also serve as “easily publishable units or marketing tools.”2,3 Given this context, we sought to compare publication trends overall and across clinical topic areas among SRMAs and RCTs over the past 22 years.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of PubMed-indexed SRMAs and RCTs published from 1995 to 2017 using the UNIX terminal window Entrez Direct (EDirect). EDirect is the primary text search and retrieval system of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The inclusion start period was set to 1995 to account for previous systematic errors in PubMed’s categorization of SRMAs prior to this time period.3 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were searched as a single category because PubMed indexes meta-analyses within systematic reviews, and up to 60% of systematic reviews include meta-analyses (Figure 1).4

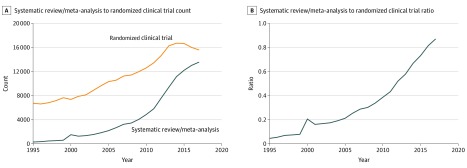

Figure 1. Published Systematic Reviews vs Randomized Clinical Trials, 1995-2017.

The graphs show the total count of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRMAs) and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) per year (A) and the ratio of SRMAs to RCTs per year from 1995 to 2017 (B). A ratio greater than 1 means more SRMAs than RCTs were published, whereas a ratio less than 1 means more RCTs than SRMAs were published.

Medical subject headings (MeSH) were used to define clinical topic areas when the term was a major topic of an article using the following heuristic for MeSH categories: medical specialty, surgical specialty, surgical procedure, disease, and anatomic system where applicable. Searches for SRMAs used the terms Systematic Review[Ptyp] OR Meta-Analysis[Ptyp], whereas RCT searches used Randomized Controlled Trial[Ptyp]. The 18 medical and surgical topic areas included in this study are noted in Figure 2, with an example of a search strategy noted in the legend. Standard identifiers (PubMed identification numbers) indexed across more than 1 specialty were only counted once. The ratio of SRMAs to RCTs was calculated for each year. A ratio greater than 1 indicates that more SRMAs than RCTs were published, whereas a ratio less than 1 indicates that more RCTs than SRMAs were published. Data analysis was performed from February 1 to February 12, 2018, and Stata version 15 (StataCorp) was used for all analyses.

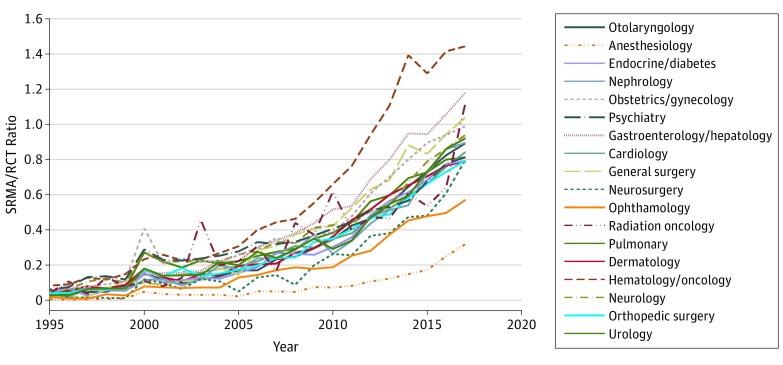

Figure 2. Trends for Publications in Selected Medical and Surgical Specialties, 1995-2017.

The graph shows the ratio of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRMAs) to randomized clinical trials (RCTs) per specialty over time. A ratio of greater than 1 means that more SRMAs than RCTs were published, and a ratio less than 1 means that more RCTs than SRMAs were published. Searches for each specialty used the National Library of Medicine’s medical subject headings for each specialty; for example, obstetrics and gynecology was searched the following phraseology (“Female Urogenital Diseases and Pregnancy Complications”[Majr] OR (“Obstetrics”[Majr] OR “Gynecology”[Majr]) OR (“Obstetric Surgical Procedures”[Majr] OR “Gynecologic Surgical Procedures”[Majr]) OR “Genitalia, Female”[Majr]).

Results

From 1995 to 2017, increases were observed in the absolute number of published SRMAs (435 in 1995 vs 20 774 in 2017) and RCTs (9486 in 1995 vs 22 560 in 2017); however, the rate of growth was significantly greater for SRMAs vs RCTs at 4676% and 138%, respectively (Figure 1). In 1995, the overall ratio (SD) of SRMAs to RCTs was 0.045 (0.02), whereas in 2017 it was 0.871 (0.26). Increases in published SRMAs and RCTs were observed for all 18 clinical topic areas (Figure 2). In 1995, the lowest ratio of SRMAs to RCTs was observed for anesthesiology (0.005) and the highest was observed for hematology/oncology (0.083); in 2017, the lowest ratio was observed for anesthesiology (0.317) and the highest was observed for hematology/oncology (1.443).

Discussion

The number of published SRMAs and RCTs has substantially increased over the last 22 years, although the rate of growth was notably greater for SRMAs. These findings update those of previous studies and are consistent with earlier studies estimating an approximately 2700% increase of SRMA indexed in PubMed.2,3 This increase may be secondary to the incorporation of the larger numbers of RCTs into SRMAs, incorporation of nonrandomized studies in SRMAs,5 and/or the proliferation of SRMAs conducted by researchers in China, who now account for production of more than one-third of all published meta-analyses.3

This study was limited by the use of PubMed, which may not be representative of overall trends in the literature.3 Additionally, our search criteria relied on the National Library of Medicine’s controlled vocabulary thesaurus, MeSH, instead of keywords to extract indexed papers.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses help to synthesize and update the literature using valuable methods for evidence-based medicine. However, an estimated 3% of SRMAs are methodologically sound, nonredundant, and provide useful clinical information.3 Although the optimal SRMA/RCT ratio has yet to be determined, an ever increasing proportion of this literature may provide minimal value, which should precipitate a reappraisal of the foundations, production, and reporting of SRMAs.6

References

- 1.Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siontis KC, Ioannidis JPA. Replication, duplication, and waste in a quarter million systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(12):e005212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioannidis JPA. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94(3):485-514. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Møller MH, Ioannidis JPA, Darmon M. Are systematic reviews and meta-analyses still useful research? we are not sure. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(4):518-520. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5039-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]