Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy and safety of acupuncture adjunctive therapy to antianginal therapies in reducing the frequency of angina attacks?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial that included 404 patients with chronic stable angina found that acupuncture on the acupoints in the disease-affected meridian significantly reduced the frequency of angina attacks compared with acupuncture on the acupoints on the nonaffected meridian, sham acupuncture, and no acupuncture.

Meaning

Adjunctive therapy with acupuncture had a significant effect in alleviating angina within 16 weeks.

This randomized clinical trial investigates the efficacy and safety of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy to antianginal therapies in reducing frequency of angina attacks in patients with chronic stable angina.

Abstract

Importance

The effects of acupuncture as adjunctive treatment to antianginal therapies for patients with chronic stable angina are uncertain.

Objective

To investigate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy to antianginal therapies in reducing frequency of angina attacks in patients with chronic stable angina.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this 20-week randomized clinical trial conducted in outpatient and inpatient settings at 5 clinical centers in China from October 10, 2012, to September 19, 2015, 404 participants were randomly assigned to receive acupuncture on the acupoints on the disease-affected meridian (DAM), receive acupuncture on the acupoints on the nonaffected meridian (NAM), receive sham acupuncture (SA), and receive no acupuncture (wait list [WL] group). Participants were 35 to 80 years of age with chronic stable angina based on the criteria of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, with angina occurring at least twice weekly. Statistical analysis was conducted from December 1, 2015, to July 30, 2016.

Interventions

All participants in the 4 groups received antianginal therapies as recommended by the guidelines. Participants in the DAM, NAM, and SA groups received acupuncture treatment 3 times weekly for 4 weeks for a total of 12 sessions. Participants in the WL group did not receive acupuncture during the 16-week study period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Participants used diaries to record angina attacks. The primary outcome was the change in frequency of angina attacks every 4 weeks from baseline to week 16.

Results

A total of 398 participants (253 women and 145 men; mean [SD] age, 62.6 [9.7] years) were included in the intention-to-treat analyses. Baseline characteristics were comparable across the 4 groups. Mean changes in frequency of angina attacks differed significantly among the 4 groups at 16 weeks: a greater reduction of angina attacks was observed in the DAM group vs the NAM group (difference, 4.07; 95% CI, 2.43-5.71; P < .001), in the DAM group vs the SA group (difference, 5.18; 95% CI, 3.54-6.81; P < .001), and in the DAM group vs the WL group (difference, 5.63 attacks; 95% CI, 3.99-7.27; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Compared with acupuncture on the NAM, SA, or no acupuncture (WL), acupuncture on the DAM as adjunctive treatment to antianginal therapy showed superior benefits in alleviating angina.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01686230

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, causing more than 17.3 million deaths per year and possibly growing to more than 23.6 million deaths annually by 2030.1 With the growth and aging of the Chinese population, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease morbidity continues to rise.2 Chronic stable angina (CSA) is the main symptom of myocardial ischemia and is associated with an increased risk of major cardiovascular events and sudden cardiac death.3 Chronic stable angina affects a mean of 3.4 million people older than 40 years each year.4 The most recent survey reported a prevalence of CSA of 9.6% in China,5 making it a considerable burden on health care and medical costs considering China’s large population.

The current aim of pharmacologic management of CSA is to prevent myocardial ischemia episodes, control symptoms, improve quality of life, and prevent cardiovascular events.6 Because of limited medical resources and lack of obvious improvement to angina with percutaneous coronary intervention,7 Chinese clinicians choose traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture in addition to antianginal treatment for CSA. Acupuncture has been used as nonpharmacologic treatment for several decades, especially to relieve symptoms of myocardial ischemia, improve cardiac function, and prevent recurrence.8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Several animal experiments have validated the protective effect of acupuncture for cardiac ischemia and remodeling.15,16,17,18,19 Several small studies have also shown that acupuncture was beneficial in treating angina,13,20,21,22,23 although others have reported discrepancies concerning the efficacy of true vs sham acupuncture (SA).14,24 The inconsistent findings may result from variations in study design and insufficient sample size.

We conducted a 20-week randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy to antianginal therapies for patients with CSA. Furthermore, we investigated whether acupuncture on the acupoints of the disease-affected meridian (DAM) was more efficacious than acupoints on the nonaffected meridian (NAM), SA, or no acupuncture (wait list [WL]).

Methods

Study Population and Protocol

We recruited patients with CSA from the outpatient and inpatient units of the departments of acupuncture and cardiology at clinical centers in 5 different regions in China. Chronic stable angina was diagnosed according to the classification criteria of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.25 Patients were enrolled in the study from October 10, 2012, to September 19, 2015. Study design and reporting were in accordance with the recommendations of the European and Chinese guidelines for the management of patients with CSA.25,26 The protocol (Supplement 1) was approved by the ethics review board of the Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and was published.27 Patients provided written informed consent.

Participants were enrolled if they fulfilled the following criteria: men or women between 35 and 80 years, presence of angina for more than 3 months with attacks occurring at least twice weekly at baseline, and no significant change in the frequency, extent, nature, and inducing and alleviation factors of angina attacks at baseline. Patients with any of the following conditions were excluded: previous myocardial infarction; severe heart failure; valvular heart disease; severe arrhythmias; atrial fibrillation; primary cardiomyopathy; psychiatric, allergic, or blood disorders; poorly controlled or uncontrolled blood pressure or blood glucose; other severe primary disease not effectively controlled; heart disease treated with acupuncture within the previous 3 months; pregnancy or lactation; or involvement in other clinical trials.

Randomization and Blinding

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in an equal ratio to the DAM, NAM, SA, or WL group via a central randomization system. The randomization sequence was generated in blocks of varying sizes and stratified according to center under the control of a central computer system. Allocation of participants was performed by an independent researcher at each clinical site who was not involved in outcome assessment. Patients in the 3 acupuncture groups were treated in a single treatment room and blinded to which acupuncture method they would receive. The outcome assessors, data collectors, and statisticians were blinded to group allocations during the study.

Interventions

All patients received antianginal therapies for 16 weeks as recommended by the guidelines, including β-blockers, aspirin, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. The choice of pharmacologic treatment was individualized, with consideration of patients’ coexisting conditions and adverse effects to the medications. Patients with an allergy to aspirin could instead be treated with clopidogrel bisulfate. Calcium channel blockers were used when patients could not tolerate or had insufficient improvement with β-blockers.

Acupuncture was performed by licensed acupuncturists with more than 3 years’ experience. Participants in all groups except the WL group received 12 sessions of acupuncture treatment (3 times weekly for 4 weeks); each session lasted 30 minutes. We chose bilateral acupoints PC6 and HT5 in the DAM group and bilateral acupoints LU9 and LU6 in the NAM group (eFigure in Supplement 2) according to traditional Chinese medicine theory based on review of the literature28,29 and consensus meetings with clinical experts. The uses of acupoints other than those prescribed were not allowed. Disposable stainless steel needles were used in acupuncture treatments. Insertion was followed by stimulation performed by lifting and thrusting the needle combined with twirling and rotating the needle sheath to produce the sensation known as deqi (sensation of soreness, numbness, distention, or radiating, which is considered to indicate effective needling). In addition, auxiliary acupuncture needles were inserted 2 mm lateral to each acupoint to a depth of 2 mm without manual stimulation. This method could ensure the electrical stimulation working on the local points. We used a HANS acupoint nerve stimulator (Model LH 200A; HANS Therapy Co) after needle insertion. The stimulation frequency was 2 Hz; intensity varied from 0.1 to 2.0 mA until patients felt comfortable. Two fixed sham acupoints were used in the SA group as in a previous study.30 Acupuncture needles were inserted at bilateral sham points for 30 minutes but without achieving a deqi sensation. The parameters of acupuncture needles and electrical stimulation were identical to those in the DAM and NAM groups. Patients in the WL group did not receive acupuncture but were instructed to schedule 12 sessions of acupuncture treatment free of charge after the 16-week study had concluded.

In case of an acute angina attack, patients were instructed to take rescue medication to relieve discomfort. Cardiologists provided nitroglycerin or nifedipine tablets31 or suxiao jiuxin wan (a traditional Chinese medicine product)32 in accordance with the Chinese guideline for the management of patients with CSA.26 The details of rescue therapies, including name, administration time, and dosage, were documented in the angina diaries. Rescue medications beyond the above 3 were considered to violate the study protocol, for which patients were excluded.

Measures

All patients were instructed to complete an angina diary on paper. At each 4-week follow-up, 2 blinded evaluators at each center reminded patients to take the diary to their outpatient visit. The primary outcome was the change in frequency of angina attacks from baseline to 16 weeks based on the angina diaries over the 4-week baseline through week 16. Secondary outcomes included mean severity of angina as assessed with a visual analog scale (score range, 0-10; higher scores indicate greater pain), the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, and rescue medication intake every 4 weeks for 16 weeks; the 6-minute walk distance test during weeks 1 through 4; and the Zung self-rating anxiety scale and the self-rating depression scale during weeks 1 through 4, 5 through 8, and 13 through 16. Additional secondary outcomes included heart rate variability as recorded by Holter monitor and Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grading at week 4. Reasons for withdrawal and acupuncture-associated adverse events (AEs), including bleeding, subcutaneous hemorrhage, hematoma, fainting, serious pain, and local infection, were recorded during the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from December 1, 2015, to July 30, 2016. A previous study13 reported an angina attack frequency of 6.1 per week in the acupuncture group and 10.6 per week in the placebo group; the clinical effect difference in that study was 4.5 attacks per week. According to the results of that previous study and our pilot study, we anticipated a reduction of 4.2 episodes in the frequency of weekly angina attacks after acupuncture treatment between the DAM and SA groups; the SD for each of the 4 groups was 8.5 episodes. Considering 2-sided P values to be deemed statistically significant at P < .05 and a power of 90%, 88 participants would be required per group (NQuery Advisor, version 4.0; Statistical Solutions). Estimating that 15% of patients might be lost to follow-up, we planned to enroll a total of 404 participants, with 101 in each group.

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes are described on the basis of the intention-to-treat population (n = 398). Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) and categorical variables are described as number and percentage. Missing data of withdrawn participants were replaced with the last-observation-carried-forward method. All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. The difference in frequency of angina attacks between baseline and the 16-week interview was not normally distributed; therefore, the data were subjected to Kruskal-Wallis analysis at a global significance level of P < .05. Secondary outcomes were evaluated with the χ2 test for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous variables. If the global test among the 4 groups was significant, the Nemenyi test or Bonferroni correction was used for post hoc analysis owing to the data distributions. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Participants and Baseline Characteristics

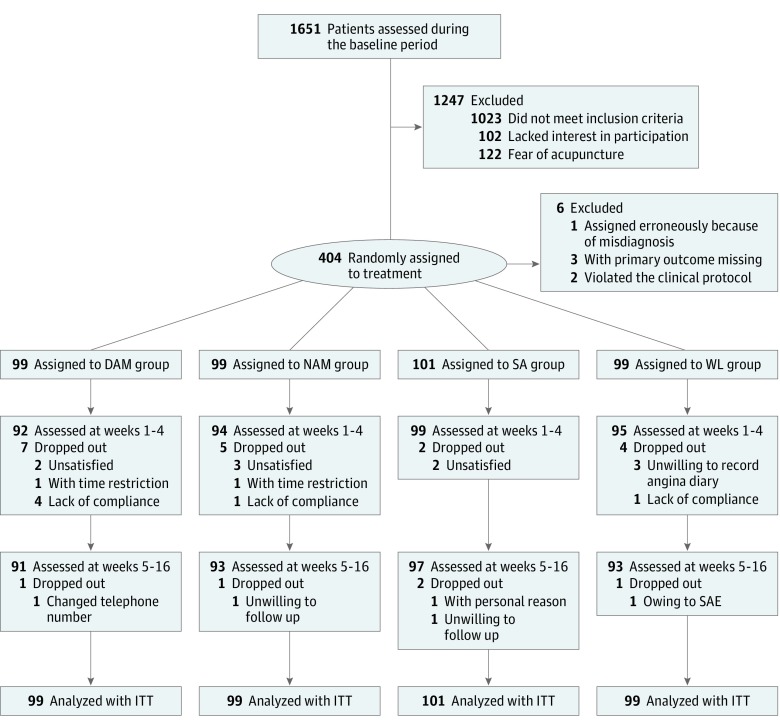

Among 1651 patients screened, 404 were enrolled at baseline. One patient was erroneously enrolled because of misdiagnosis at the end of the baseline period, 3 patients never received a treatment and lost contact after baseline, and another 2 patients violated the clinical protocol during the baseline period. The remaining 398 patients were included in the intention-to-treat population. A total of 381 patients (95.7%) received 12 sessions of acupuncture; 374 of the 404 patients enrolled (92.6%) completed 16 weeks of follow-up (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients at baseline and acupuncture expectations before treatment.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Screening, Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

DAM indicates disease-affected meridian; ITT, intention to treat; NAM, nonaffected meridian; SA, sham acupuncture; SAE, serious adverse effect; and WL, wait list.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients in Intention-to-Treat Analysis.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAM (n = 99) | NAM (n = 99) | SA (n = 101) | WL (n = 99) | All (N = 398) | |

| Women | 64 (64.6) | 67 (67.7) | 62 (61.4) | 60 (60.6) | 253 (63.6) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.5 (9.9) | 61.8 (9.8) | 62.4 (8.9) | 63.4 (10.3) | 62.6 (9.7) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 23.2 (3.0) | 23.2 (3.0) | 24.2 (3.0) | 23.8 (3.0) | 23.6 (3.0) |

| Duration of illness, mean (SD), mo | 46.2 (47.9) | 59.9 (84.3) | 51.3 (51.1) | 61.5 (69.3) | 54.7 (64.8) |

| Family history, yes | 17 (17.2) | 17 (17.2) | 27 (26.7) | 25 (25.3) | 86 (21.6) |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 184.1 (45.2) | 186.0 (36.3) | 180.2 (41.0) | 182.9 (43.3) | 181.7 (41.4) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 142.6 (85.0) | 153.2 (100.1) | 167.4 (136.4) | 142.6 (92.1) | 150.5 (105.4) |

| Resting blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | 126.1 (13.7) | 126.1 (12.0) | 127.7 (13.0) | 126.6 (10.7) | 126.6 (12.4) |

| Diastolic | 75.4 (8.9) | 77.1 (8.1) | 75.4 (9.2) | 75.7 (8.4) | 75.9 (8.7) |

| Fasting blood glucose, mean (SD), mg/dL | 101.3 (19.5) | 98.9 (17.7) | 102.9 (19.8) | 102.0 (25.4) | 101.3 (20.7) |

| Antianginal medications | |||||

| β-Blockers | 89 (89.9) | 92 (92.9) | 87 (86.1) | 91 (91.9) | 359 (90.2) |

| Aspirin or clopidogrel | 99 (100) | 99 (100) | 101 (100) | 99 (100) | 398 (100) |

| Statins | 93 (93.9) | 96 (97.0) | 94 (93.1) | 97 (98.0) | 380 (95.5) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 90 (90.9) | 88 (88.9) | 94 (93.1) | 93 (93.9) | 365 (91.7) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 10 (10.1) | 9 (9.1) | 12 (11.9) | 8 (8.1) | 39 (9.8) |

| Long-lasting nitrates | 5 (5.05) | 4 (4.04) | 7 (6.93) | 3 (3.03) | 19 (4.77) |

| Previous treatment for acute angina attack | |||||

| Nitroglycerin | 25 (25.3) | 32 (32.3) | 24 (23.8) | 27 (27.3) | 108 (27.1) |

| Self-relieved | 47 (47.5) | 49 (49.5) | 49 (48.5) | 50 (50.2) | 195 (49.0) |

| Others | 23 (23.2) | 16 (16.2) | 24 (23.8) | 19 (19.2) | 82 (20.6) |

| Previous use of PCI | 31 (31.0) | 33 (32.7) | 34 (33.7) | 22 (21.8) | 120 (30.2) |

| No previous use of acupuncture for CSA | 99 (100) | 99 (100) | 101 (100) | 99 (100) | 398 (100) |

| Patient expectation of acupuncture success | |||||

| None | 5 (5.1) | 5 (5.1) | 8 (7.9) | 6 (6.1) | 24 (6.0) |

| Slight | 40 (40.4) | 38 (38.4) | 37 (36.6) | 38 (38.4) | 153 (38.4) |

| Some | 27 (27.3) | 34 (34.3) | 34 (33.7) | 32 (32.3) | 127 (31.9) |

| Significant | 27 (27.3) | 22 (22.2) | 22 (21.8) | 23 (23.2) | 94 (23.6) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CSA, chronic stable angina; DAM, disease-affected meridian; NAM, nonaffected meridian; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SA, sham acupuncture; WL, wait list.

SI conversion factors: To convert total cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113; and glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0555.

Primary Outcome

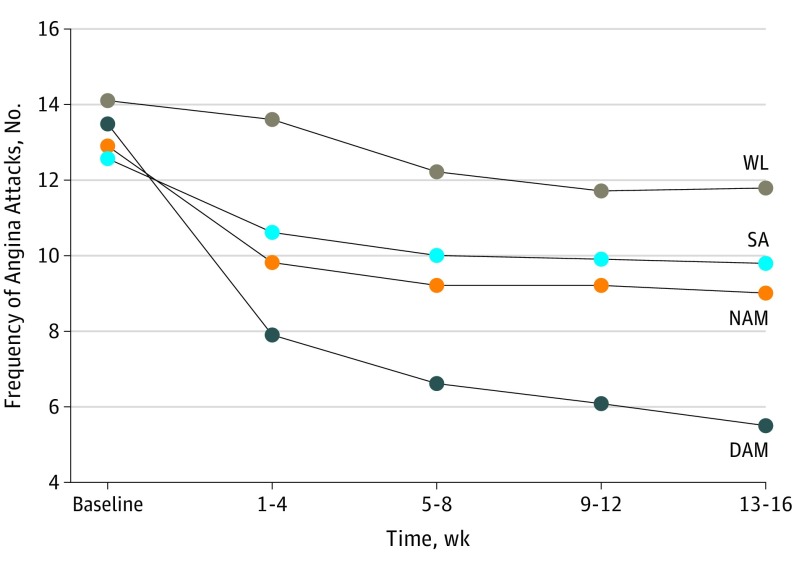

We included patients with CSA who had angina attacks at least twice per week during the baseline period; the mean frequency of angina attacks was 13.31 during the 4-week baseline period. Changes in the frequency of angina attacks over 4-week periods differed significantly among the 4 groups at 16 weeks after randomization (Table 2). The frequency of angina attacks was significantly lower in the DAM group than in the other 3 groups at each interview from weeks 4 to 16 (Figure 2). The frequency decreased by 7.96 attacks in the DAM group, by 3.89 attacks in the NAM group, by 2.78 attacks in the SA group, and by 2.33 attacks in the WL group. A greater reduction was observed in the DAM group than in the other groups: 4.07 fewer attacks than in the NAM group (95% CI, 2.43-5.71; P < .001), 5.18 fewer attacks than in the SA group (95% CI, 3.54-6.81; P < .001), and 5.63 fewer attacks than in the WL group (95% CI, 3.99-7.27; P < .001). The per-protocol analysis showed similar results.

Table 2. Angina Diary–Based Outcome Measurements During the Study.

| Outcome Measure | DAM (n = 99) | NAM (n = 99) | SA (n = 101) | WL (n = 99) | P Value | Value of Pairwise Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAM vs NAM | DAM vs SA | DAM vs WL | |||||||||

| Effect Size (95% CI) | P Valuea | Effect Size (95% CI) | P Valuea | Effect Size (95% CI) | P Valuea | ||||||

| Difference from baseline in frequency of angina attacks, mean (SD), No. | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 13.52 (5.93) | 12.94 (7.28) | 12.62 (5.64) | 14.14 (10.39) | .51 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 5.57 (3.70) | 3.14 (4.07) | 2.00 (4.19) | 0.48 (4.50) | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 6.86 (4.24) | 3.72 (4.71) | 2.55 (4.34) | 1.94 (7.35) | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 |

| 9-12 | 7.32 (4.49) | 3.65 (4.59) | 2.67 (4.99) | 2.38 (7.05) | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 |

| 13-16 | 7.96 (5.04) | 3.89 (4.77) | 2.78 (6.08) | 2.33 (7.27) | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 | NA | <.001 |

| Pain severity of angina, mean (SD), VAS scoreb | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 3.75 (1.31) | 3.66 (1.37) | 3.70 (1.11) | 3.58 (1.18) | .80 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 3.07 (1.33) | 3.26 (1.25) | 3.43 (1.07) | 3.51 (1.23) | .07 | −0.15 (−0.43 to 0.13) | .30 | −0.30 (−0.58 to −0.02) | .04 | −0.34 (−0.62 to −0.06) | .02 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 2.84 (1.40) | 3.02 (1.16) | 3.27 (1.17) | 3.44 (1.33) | .007 | −0.14 (−0.42 to 0.14) | .22 | −0.33 (−0.61 to −0.05) | .009 | −0.44 (−0.72 to −0.16) | .001 |

| 9-12 | 2.52 (1.49) | 3.12 (1.30) | 3.28 (1.27) | 3.42 (1.30) | <.001 | −0.43 (−0.71 to −0.15) | .001 | −0.55 (−0.83 to −0.26) | <.001 | −0.64 (−0.93 to −0.36) | <.001 |

| 13-16 | 2.37 (1.60) | 3.11 (1.40) | 3.17 (1.23) | 3.37 (1.29) | <.001 | −0.49 (−0.77 to −0.21) | <.001 | −0.56 (−0.84 to −0.28) | <.001 | −0.69 (−0.97 to −0.40) | <.001 |

| Use of rescue medicine, No. (%) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 26 (26.0) | 33 (32.7) | 24 (23.5) | 31 (30.7) | .45 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 22 (22.0) | 24 (23.8) | 25 (24.5) | 27 (26.7) | .78 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 14 (14.0) | 20 (19.8) | 21 (20.6) | 25 (24.8) | .50 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 9-12 | 11 (11.0) | 24 (23.8) | 19 (18.6) | 26 (25.7) | .09 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13-16 | 11 (11.0) | 22 (21.8) | 17 (16.7) | 23 (22.8) | .24 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Score of SAS, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 39.97 (7.69) | 41.12 (8.22) | 40.92 (6.96) | 41.14 (7.32) | .67 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 37.66 (7.71) | 39.00 (6.63) | 39.38 (6.55) | 39.97 (7.33) | .15 | −0.19 (−0.46 to 0.09) | .20 | −0.24 (−0.52 to 0.04) | .11 | −0.31 (−0.59 to −0.03) | .03 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 36.79 (7.55) | 37.94 (6.46) | 38.83 (6.42) | 39.10 (7.07) | .10 | −0.16 (−0.44 to 0.12) | .26 | 0.29 (−0.57 to −0.01) | .04 | −0.32 (−0.59 to −0.03) | .02 |

| 13-16 | 35.70 (7.62) | 37.40 (6.64) | 38.22 (6.35) | 38.56 (6.55) | .02 | −0.24 (−0.52 to 0.04) | .09 | −0.36 (−0.64 to −0.08) | .01 | −0.40 (−0.68 to −0.12) | .005 |

| Score of SDS, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 39.83 (8.53) | 41.37 (10.49) | 41.73 (9.05) | 41.26 (8.46) | .48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 38.09 (8.57) | 39.24 (9.65) | 41.13 (9.31) | 40.89 (8.91) | .07 | −0.13 (−0.40 to 0.15) | .39 | −0.34 (−0.62 to −0.06) | .02 | −0.32 (−0.60 to −0.04) | .04 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 36.95 (7.71) | 38.49 (9.30) | 40.34 (8.41) | 39.46 (8.28) | .04 | −0.18 (−0.46 to 0.10) | .21 | −0.42 (−0.70 to −0.14) | .006 | −0.31 (−0.59 to −0.03) | .04 |

| 13-16 | 35.96 (7.41) | 38.46 (9.55) | 39.90 (8.15) | 39.16 (7.60) | .008 | −0.29 (−0.57 to −0.01) | .04 | −0.51 (−0.79 to −0.22) | .001 | −0.43 (−0.71 to −0.14) | .009 |

| 6-Minute walk distance test, mean (SD), m | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 379.50 (68.47) | 394.90 (82.18) | 378.80 (78.89) | 381.0 (83.61) | .42 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 408.60 (65.02) | 415.10 (82.63) | 384.20 (75.91) | 385.0 (77.80) | .006 | −0.09 (−0.37 to 0.19) | .56 | 0.34 (0.06 to 0.62) | .03 | 0.33 (0.05 to 0.61) | .03 |

Abbreviations: DAM, disease-affected meridian; NA, not applicable; NAM, nonaffected meridian; SA, sham acupuncture; SAS, self-rating anxiety scale; SDS, self-rating depression scale; VAS, visual analog scale; WL, wait list.

P value based on the Nemenyi method or Bonferroni adjustment in pairwise comparison based on data distribution. P values based on Kruskal-Wallis analysis between the 4 groups in difference from baseline in frequency of angina attacks. P values based on analysis of variance between the 4 groups in VAS, use of rescue medicine, SAS, SDS, and the 6-minute walk distance test.

Score range is from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater pain.

Figure 2. Frequency of Angina Attacks Over Time During the Study.

DAM indicates disease-affected meridian; NAM, nonaffected meridian; SA, sham acupuncture; and WL, wait list.

Secondary Outcomes

The mean (SD) visual analog scale score was significantly lower in the DAM group than in the others at each time point from weeks 8 to 16 (weeks 5-8: DAM group, 2.84 [1.40]; NAM group, 3.02 [1.16]; SA group, 3.27 [1.17]; and WL group, 3.44 [1.33]; P = .007; weeks 9-12: DAM group, 2.52 [1.49]; NAM group, 3.12 [1.30]; SA group, 3.28 [1.27]; and WL group, 3.42 [1.30]; P < .001; and weeks 13-16: DAM group, 2.37 [1.60]; NAM group, 3.11 [1.40]; SA group, 3.17 [1.23]; and WL group, 3.37 [1.29]; P < .001). There was no difference in the number of patients using rescue medication among the 4 groups during the 16-week study period. Moreover, there were no differences among the 4 groups in Zung self-rating anxiety scale or self-rating depression scale scores at the end of treatment, but the DAM group showed significantly more improvement compared with the SA and WL groups at 5 to 8 weeks (DAM group vs SA group: effect size, 0.29; 95% CI, –0.57 to –0.01; P = .04; DAM group vs WL group: effect size, –0.32; 95% CI, –0.59 to –0.03; P = .02) and at 13 to 16 weeks (DAM group vs SA group: effect size, –0.36; 95% CI, –0.64 to –0.08; P = .01; DAM group vs WL group: effect size, –0.40; 95% CI, –0.68 to –0.12; P = .005) in self-rating anxiety scale (Table 2).

The Seattle Angina Questionnaire was used to assess the physical function of angina (Table 3). Angina stability scores and angina frequency improved significantly more in the DAM group than in other groups at each interview during the treatment and follow-up periods. Compared with other groups, the DAM group had significantly higher mean (SD) treatment satisfaction scores at each follow-up except when compared with the NAM group at 1 to 4 weeks (1-4 weeks: DAM group, 72.25 [12.47]; NAM group, 69.15 [13.69]; SA group, 66.07 [13.34]; and WL group, 59.26 [15.77]; P < .001; 5-8 weeks: DAM group, 73.08 [12. 70]; NAM group, 67.49 [13.03]; SA group, 65.55 [12.56]; and WL group, 61.33 [12.95]; P < .001; 9-12 weeks: DAM group, 72.94 [11.89]; NAM group, 67.68 [12.22]; SA group, 65.73 [12.56]; and WL group, 63.45 [11.92]; P < .001; and 13-16 weeks: DAM group, 74.44 [12.54]; NAM group, 66.62 [12.61]; SA group, 65.68 [13.23]; and WL group, 63.19 [13.77]; P < .001). Significant differences in physical limitation score were found among the 4 groups only at weeks 8 and 16 within the follow-up period. No significant difference was detected among the groups in quality of life score. Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grade was assessed at baseline and at the end of treatment (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). There were significant differences among the 4 groups in the proportion of patients with no change or with deterioration of 1 or more classes. On the 6-minute walk distance test, patients in the DAM group walked longer distances than those in the SA and WL groups at the end of week 4 but not longer than patients in the NAM group.

Table 3. SAQ Measurements During the Entire Study.

| Outcome Measure | DAM (n = 99) | NAM (n = 99) | SA (n = 101) | WL (n = 99) | P Value | Value of Pairwise Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAM vs NAM | DAM vs SA | DAM vs WL | |||||||||

| Effect Size (95% CI) | P Valuea | Effect Size (95% CI) | P Valuea | Effect Size (95% CI) | P Valuea | ||||||

| Physical limitation score, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 54.21 (13.89) | 55.33 (13.51) | 54.63 (12.69) | 54.64 (12.45) | .95 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 58.41 (12.29) | 58.44 (10.87) | 56.54 (12.11) | 55.37 (11.58) | .20 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 60.58 (9.79) | 59.31 (9.73) | 57.26 (11.50) | 56.17 (11.04) | .02 | 0.13 (−0.15 to 0.41) | .41 | 0.31 (0.03 to 0.59) | .03 | 0.42 (0.14 to 0.70) | .005 |

| 9-12 | 60.54 (9.60) | 58.71 (9.95) | 57.07 (11.54) | 56.95 (11.11) | .07 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13-16 | 62.07 (10.11) | 59.20 (9.60) | 57.37 (11.68) | 55.68 (10.61) | <.001 | 0.29 (0.01 to 0.57) | .07 | 0.43 (0.15 to 0.71) | .002 | 0.62 (0.33 to 0.90) | <.001 |

| Angina stability score, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 48.48 (17.06) | 48.48 (19.17) | 49.01 (18.00) | 46.72 (16.62) | .81 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 86.96 (15.50) | 73.67 (23.00) | 64.90 (24.98) | 54.26 (22.49) | <.001 | 0.68 (0.39 to 0.96) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.76 to 1.35) | <.001 | 1.69 (1.36 to 2.01) | <.001 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 72.55 (24.88) | 60.75 (26.94) | 60.97 (23.56) | 56.38 (20.72) | <.001 | 0.46 (0.17 to 0.74) | .001 | 0.48 (0.19 to 0.76) | <.001 | 0.71 (0.42 to 0.99) | <.001 |

| 9-12 | 69.44 (23.64) | 53.49 (24.34) | 56.89 (22.07) | 58.24 (22.42) | <.001 | 0.66 (0.38 to 0.95) | <.001 | 0.55 (0.26 to 0.83) | <.001 | 0.49 (0.20 to 0.77) | .001 |

| 13-16 | 70.83 (23.18) | 55.98 (21.41) | 52.58 (22.39) | 53.23 (20.27) | <.001 | 0.67 (0.38 to 0.95) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.09) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.09) | <.001 |

| Angina frequency score, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 68.89 (9.99) | 67.47 (11.72) | 69.21 (11.20) | 67.68 (11.50) | .61 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 77.61 (8.82) | 74.36 (8.87) | 72.32 (10.77) | 69.26 (11.85) | <.001 | 0.37 (0.09 to 0.65) | .03 | 0.54 (0.25 to 0.82) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.09) | <.001 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 80.54 (9.99) | 75.59 (10.47) | 73.78 (10.80) | 69.79 (12.27) | <.001 | 0.48 (0.20 to 0.76) | .002 | 0.65 (0.36 to 0.93) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.66 to 1.25) | <.001 |

| 9-12 | 83.00 (10.43) | 75.27 (9.04) | 74.49 (11.04) | 70.96 (11.46) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.08) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.08) | <.001 | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.39) | <.001 |

| 13-16 | 84.11 (11.01) | 75.76 (10.40) | 75.36 (11.19) | 70.97 (12.25) | <.001 | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.07) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.50 to 1.07) | <.001 | 1.13 (0.82 to 1.42) | <.001 |

| Treatment satisfaction score, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 57.87 (18.04) | 60.78 (15.99) | 59.70 (15.99) | 58.88 (16.73) | 0.66 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 72.25 (12.47) | 69.15 (13.69) | 66.07 (13.34) | 59.26 (15.77) | <.001 | 0.24 (–0.04 to 0.52) | .13 | 0.48 (0.20 to 0.76) | .002 | 0.91 (0.62 to 1.20) | <.001 |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 73.08 (12.70) | 67.49 (13.03) | 65.55 (12.56) | 61.33 (12.95) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.15 to 0.71) | .003 | 0.60 (0.31 to 0.88) | <.001 | 0.92 (0.62 to 1.21) | <.001 |

| 9-12 | 72.94 (11.89) | 67.68 (12.22) | 65.73 (12.56) | 63.45 (11.92) | <.001 | 0.44 (0.15 to 0.72) | .004 | 0.59 (0.30 to 0.87) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.50 to 1.08) | <.001 |

| 13-16 | 74.44 (12.54) | 66.62 (12.61) | 65.68 (13.23) | 63.19 (13.77) | <.001 | 0.62 (0.33 to 0.90) | <.001 | 0.68 (0.39 to 0.96) | <.001 | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.14) | <.001 |

| QoL score, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 42.42 (17.86) | 43.60 (18.09) | 41.75 (15.92) | 43.10 (14.87) | .87 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment for 1-4 wk | 50.45 (17.00) | 47.43 (18.00) | 45.45 (15.26) | 46.45 (16.28) | .19 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| After treatment, wk | |||||||||||

| 5-8 | 51.90 (16.16) | 47.31 (17.38) | 46.34 (15.51) | 46.28 (15.73) | .06 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 9-12 | 51.20 (16.12) | 48.39 (16.68) | 47.19 (15.69) | 48.14 (15.22) | .36 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13-16 | 52.59 (15.18) | 47.83 (16.66) | 48.20 (16.15) | 48.21 (14.00) | .12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: DAM, disease-affected meridian; NA, not applicable; NAM, nonaffected meridian; QoL, quality of life; SA, sham acupuncture; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; WL, wait list.

Based on the Bonferroni adjustment in pairwise comparison and on analysis of variance.

Holter monitoring was recorded on the first day after enrollment and after 4 weeks of treatment. Heart rate variability recordings were completed for 258 patients from 4 clinical centers. The heart rate variability data at the Yunnan center (69 cases) were recorded by a machine that was different from that used at the other centers, so those data were not included in analysis. There were no differences in the time-domain or frequency-domain values for 24-hour heart rate variability among the groups at the end of treatment except for the low frequency to high frequency ratio (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Safety

A total of 16 patients reported acupuncture-related AEs. Among these, 8 AEs were related to acupuncture treatment, including 5 patients who had subcutaneous hemorrhage in the area where the needle was inserted and 3 patients who experienced a tingling sensation after needle insertion. Eight patients reported sleeplessness during the study period. All AEs were reported as mild or moderate; none required special medical interventions. All patients recovered fully from the AEs and remained in the trial. Only 1 patient in the WL group experienced a serious AE. She died due to acute myocardial infarction during weeks 5 to 8 before receiving acupuncture treatment.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the largest multicenter clinical trial to show the beneficial effect of true acupuncture as adjunctive treatment for CSA within 16 weeks and is the first to explore acupoint specificity in this field. We found that acupuncture on the DAM had superior and clinically relevant benefits in reducing angina frequency and pain intensity to a greater degree than acupuncture on a NAM, SA, or no acupuncture (WL group). Improvements in 6-minute walk distance test results, Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grade, and most metrics of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire were also found. Moreover, compared with SA and no acupuncture, acupuncture on the DAM resulted in better regulation of anxiety and depression within the 12 weeks after treatment than at the end of the treatment period. Acupuncture on the DAM causes autonomic remodeling by improving the balance between the vagus nerve and sympathetic nervous system during treatment.

The findings of the current study demonstrate that adjunctive acupuncture on the DAM was more effective than antianginal therapy alone. Our findings are consistent with those of a previous systematic review22 that examined the effectiveness of combined acupuncture and antianginal treatment vs antianginal medications alone. We also found that acupuncture on the DAM was clinically beneficial and superior to SA for angina treatment. The prior 2 studies found no significant difference between true acupuncture and SA in improving the rate of angina attacks.14,20 This inconsistency may be attributed to several factors. The first is the difference in acupoint prescription. In the present study, we chose PC6, located on the pericardium meridian, and HT5, located on the heart meridian, which are the DAMs based on the traditional Chinese medicine theory of syndrome differentiation. These 2 main acupoints were also used in a Swedish study, which showed that acupuncture had additional beneficial effects in patients with stable angina.13 Second, electroacupuncture was applied in our study because of its advantages compared with manual acupuncture in relieving pain and reducing response times.33 Furthermore, electroacupuncture pretreatment has been used to prevent myocardial injury in patients with coronary artery disease.8 Electroacupuncture results in more reproducible stimulation than manual acupuncture in clinical application. Finally, angina severity and attack frequency during the baseline period might have influenced the therapeutic effects. We included patients with CSA who had angina attacks at least twice per week during the baseline period; the mean frequency of angina attacks was 13.31 during the 4-week baseline period. Ballegaard et al14 had nearly the same requirement for number of angina attacks as our study, but the mean frequency of angina attacks in that study was approximately 20 in the 3 weeks before treatment. In another study of patients with severe, stable, medically resistant angina, the mean frequency of angina attacks was 69.5 per 3 weeks during the baseline period.20 True acupuncture was found to increase cardiac work capacity significantly more than SA in these 2 studies, but no significant difference was observed between true acupuncture and SA either at the end of treatment or during posttreatment follow-up. Patients with mild to moderate angina may benefit most from adjuvant acupuncture therapy.

Compared with acupuncture on the NAM, acupuncture on the DAM showed significant superiority in the primary outcome and in most of the subscales of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire at the end of therapy, effects that lasted to 12 weeks after treatment ended. Acupuncture on the DAM was more effective than on the NAM in alleviating pain severity during the follow-up period, although not at the end of treatment. The LU9 and LU6 acupoints are located on the lung meridian, which is not affected directly by CSA in traditional Chinese medicine. Although results with acupuncture on the NAM were inferior to those with acupuncture on the DAM, the NAM was still associated with clinical improvement in our study. We speculate that the varied efficacy between the DAM and NAM and the benefit of acupuncture on the DAM relate to acupoint specificity.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, we used a standard prescription to evaluate the efficacy of adjunctive acupuncture. We did not use personalized treatment planning based on the acupuncturist’s experience, which might have caused performance bias. Second, we measured the proportion of patients taking rescue medication during episodes of angina attacks, but the dosages were not analyzed because more than 1 type of medication is used in patients with CSA in China. Third, we did not perform subgroup analysis of the effects of acupuncture on patients with angina after percutaneous coronary intervention because of the original purpose of the study. Finally, this study was limited by small study size; patients were healthy at baseline (excluding those with prior myocardial infarction or heart failure), so this finding might not generalize to sicker patients; and long-term relief (beyond 16 weeks) after the intervention was unknown.

Conclusions

Acupuncture was safely administered in patients with mild to moderate CSA. Compared with the NAM, SA, and WL groups, adjunctive acupuncture on the DAM showed superior benefits in CSA treatment within 16 weeks. Acupuncture should be considered as one option for adjunctive treatment in alleviating angina.

Study Protocol

eFigure. Location of Acupoints and Nonacupoints

eTable 1. CCS Angina Grade and 6WMD During the Baseline and at the End of Therapy

eTable 2. HRV During the Baseline and at the End of Therapy

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Gao R, Liu L, et al. Summary of cardiovascular disease report in China—2016. Chin Circ J. 2017;32(6):521-531. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohman EM. Clinical practice: chronic stable angina. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(12):1167-1176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1502240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=26673558&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greaves K, Chen Y, Appadurai V, Hu Z, Schofield P, Chen R. The prevalence of doctor-diagnosed angina in 4314 older adults in China and comparison with the Rose Angina Questionnaire: the 4 Province Study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(2):627-628. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson RA, O’Flynn N; Guideline Development Group . Management of stable angina: summary of NICE guidance. Heart. 2012;98(6):500-507. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi HM, et al. ; ORBITA investigators . Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10115):31-40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32714-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, Liang D, Wang F, et al. Efficacy of electroacupuncture pretreatment for myocardial injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized clinical trial with a 2-year follow-up. Int J Cardiol. 2015;194:28-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bueno EA, Mamtani R, Frishman WH. Alternative approaches to the medical management of angina pectoris: acupuncture, electrical nerve stimulation, and spinal cord stimulation. Heart Dis. 2001;3(4):236-241. doi: 10.1097/00132580-200107000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho FM, Huang PJ, Lo HM, et al. Effect of acupuncture at nei-kuan on left ventricular function in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Chin Med. 1999;27(2):149-156. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X99000197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta PK, Polk DM, Zhang X, et al. A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture in stable ischemic heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(2):367-374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannheimer C, Carlsson CA, Emanuelsson H, Vedin A, Waagstein F, Wilhelmsson C. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in patients with severe angina pectoris. Circulation. 1985;71(2):308-316. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.71.2.308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter A, Herlitz J, Hjalmarson A. Effect of acupuncture in patients with angina pectoris. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(2):175-178. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballegaard S, Pedersen F, Pietersen A, Nissen VH, Olsen NV. Effects of acupuncture in moderate, stable angina pectoris: a controlled study. J Intern Med. 1990;227(1):25-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou W, Ko Y, Benharash P, et al. Cardioprotection of electroacupuncture against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulation of cardiac norepinephrine release. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(9):H1818-H1825. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00030.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma L, Cui B, Shao Y, et al. Electroacupuncture improves cardiac function and remodeling by inhibition of sympathoexcitation in chronic heart failure rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306(10):H1464-H1471. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00889.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao J, Fu W, Jin Z, Yu X. Acupuncture pretreatment protects heart from injury in rats with myocardial ischemia and reperfusion via inhibition of the beta(1)-adrenoceptor signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2007;80(16):1484-1489. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Lu SF, Hu CJ, et al. Electro-acupuncture at neiguan pretreatment alters genome-wide gene expressions and protects rat myocardium against ischemia-reperfusion. Molecules. 2014;19(10):16158-16178. doi: 10.3390/molecules191016158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longhurst J. Acupuncture’s cardiovascular actions: a mechanistic perspective. Med Acupunct. 2013;25(2):101-113. doi: 10.1089/acu.2013.0960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballegaard S, Jensen G, Pedersen F, Nissen VH. Acupuncture in severe, stable angina pectoris: a randomized trial. Acta Med Scand. 1986;220(4):307-313. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb02770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M, Chen H, Lu S, Wang J, Zhang W, Zhu B. Impacts on neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients of chronic stable angina pectoris treated with acupuncture at Neiguan (PC 6) [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2015;35(5):417-421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu C, Ji K, Cao H, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for angina pectoris: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:90. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0586-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballegaard S, Karpatschoff B, Holck JA, Meyer CN, Trojaborg W. Acupuncture in angina pectoris: do psycho-social and neurophysiological factors relate to the effect? Acupunct Electrother Res. 1995;20(2):101-116. doi: 10.3727/036012995816357113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballegaard S, Meyer CN, Trojaborg W. Acupuncture in angina pectoris: does acupuncture have a specific effect? J Intern Med. 1991;229(4):357-362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King SB III, Smith SC Jr, Hirshfeld JW Jr, et al. ; 2005 Writing Committee Members . 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: 2007 Writing Group to review new evidence and update the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention, writing on behalf of the 2005 Writing Committee. Circulation. 2008;117(2):261-295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinese Society of Cardiology, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board, Chinese Journal of Cardiology . Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic stable angina [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2007;35(3):195-206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li D, Yang M, Zhao L, et al. Acupuncture for chronic, stable angina pectoris and an investigation of the characteristics of acupoint specificity: study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:50. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He D, Ren Y, Tang Y, Liang F. Application of data-mining to analyze characteristics of meridians and acupoints selected for acumoxibustion treatment of chest blockage in ancient literatures of different periods of ancient days. Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;40(6):1209-1213. [Google Scholar]

- 29.He D, Ren Y, Tang Y, Liang F. Analysis of characteristics of meridians and acupoints selected for modern acu-moxibustion treatment of angina pectoris based on data mining. Liaoning J Trad Chin Med. 2013;40(11):2195-2197. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao L, Chen J, Li Y, et al. The long-term effect of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):508-515. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; American College of Physicians; American Association for Thoracic Surgery; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons . 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):e44-e164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan X, Zhou L, Wu T, et al. Chinese herbal medicine suxiao jiuxin wan for angina pectoris. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004473. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004473.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schliessbach J, van der Klift E, Arendt-Nielsen L, Curatolo M, Streitberger K. The effect of brief electrical and manual acupuncture stimulation on mechanical experimental pain. Pain Med. 2011;12(2):268-275. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol

eFigure. Location of Acupoints and Nonacupoints

eTable 1. CCS Angina Grade and 6WMD During the Baseline and at the End of Therapy

eTable 2. HRV During the Baseline and at the End of Therapy

Data Sharing Statement