Abstract

Effective tumor diagnosis and therapy have always been a significant but challenging issue. Although nanomedicine has shown great potential for improving the outcomes of tumor diagnosis and therapy, the nonspecial targeted distribution of nanomedicine agents in the whole body causes a low diagnosis signal-to-noise ratio and a potential risk of systemic toxicity. Recently, the development of smart nanomedicine agents with diagnosis and therapy functions that can only be activated by the tumor microenvironment (TME) is regarded as an effective strategy to improve the theranostic sensitivity and selectivity, as well as reduce the potential side effects during treatment. This article will introduce and summarize the latest achievements in the design and fabrication of TME-responsive smart nanomedicine agents, and highlight their prospects for enhancing tumor diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: tumor microenvironment, smart nanomedicine agents, theranostic agents, smart nanoprobes, smart nanocarriers

Introduction

Malignant tumor is one of the key diseases leading to mortality around the word. Owing to the limited outcomes and undesirable side effects of conventional therapy (such as surgery and chemotherapy), many efforts from various fields have been devoted to exploring effective and safe therapeutic modalities and agents.1–3 In the past two decades, a number of imaging technology and therapeutic modalities of minimally invasive nature have shown great promise toward this goal.4–7 For example, photodynamic therapy, which employed a photosensitizer to generate cytotoxic singlet oxygen to kill tumor cells in the specified position irradiated by excitation light, displays high treat selectivity and leaves little or no scarring.8,9 These promising imaging technologies and therapeutic modalities are boosted by the unceasing emergence of nanomedicine agents that possess versatile physiochemical properties, such as fluorescence,10 magnetism,11 near-infrared (NIR) absorption,12 and porous structures.13 For instance, gold nanoparticles with strong NIR absorption can be utilized for photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy.14 Porous silicon and metal–organic frameworks with high porosity and large surface area can be used as carriers for delivering anticancer drugs.15,16

One of the major concerns for nanomedicine agents in practical application is their nonspecial targeted distribution in the body.17 Although nanoparticles are preferred to accumulate in the tumor area (because of the EPR effect) and the accumulated benefits can be further improved through decorating tumor-specific targeting moieties (eg, peptides, aptamers, and antibodies) on the surface of the nanoparticles, still only a very small amount (about 0.7%) of administered materials can reach the tumor.18 Indeed, most of the nanoparticles are sequestered by the reticuloendothelial system. As a result, the diagnosis signals and therapeutic functions appear in the whole body, especially in the reticuloendothelial-system-rich organs (eg, liver and kidney), leading to a low diagnosis signal-to-noise ratio and risk of systemic toxicity.19,20

To overcome these challenge, great research interest has recently been focused on exploring stimulus-responsive/smart nanomedicine agents, whose diagnosis and therapy functions can only be activated at the target site by special exogenous stimuli (eg, light, magnetism, ultrasound) or endogenous stimuli (eg, pH, redox, enzyme).17,21–24 Because of the abnormal growth and metabolism of the tumor cells, the tumor tissues are usually involved in a variety of unique physicochemical microenvironments, including acidic pH, hypoxia, high level of glutathione (GSH) and H2O2, as well as overexpressed enzymes and proteins, etc.25 These unique microenvironments are undesirable because they are usually beneficial for tumor proliferation, invasion, adhesion, and antitherapy,26,27 while, on the other hand, they can be regarded as endogenous stimuli for designing tumor-specific smart nanomedicine agents.17,28 Typically, the theranostic functions of these smart nanomedicine agents are in “closed” state in normal tissues, but become “on” state when taken up by tumor cells, giving high theranostic sensitive and selectivity, as well as low side effects.29 Furthermore, the diagnosis signals activated by the tumor microenvironment (TME) may in turn reflect the change of the physiological parameters of the tumor cells/tissues, providing valuable information for doctors to alter the theranostic strategy in real time.30

Up to now, a great number of TME-responsive smart nanomedicine agents have been explored, and many of them showed great potential for application in tumor diagnosis and treatment.1,31 Based on the functions of these smart nanomedicine agents, they can be mainly divided into three types: 1) smart nanoprobes for specific tumor imaging and detection; 2) smart nanocarriers for antitumor drug delivery and controlling release; and 3) smart therapy/theranostic agents that possess functions of treatment or combine both functions of diagnosis and treatment. In this review article, we will introduce and discuss recent developments in the design and fabrication of smart nanomedicine agents for enhancing tumor diagnosis and treatment by exploiting the TME, including acidic pH and overexpressed GSH, H2O2, and H2S (Table 1).

Table 1.

Paradigms of smart nanomedicine agents for cancer

| Nanomedicine type | Function | Targeted TEM | Imaging method | Therapeutic strategy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-thiophene-4 | pH-responsive nanoprobe | Mild acidity | FL | / | 41 |

| Fe3O4-ZIF-8 | pH/GSH-responsive nanoprobe | Mild acidity and GSH | MRI | / | 42 |

| C–HSA–BOPx–IR825 | pH-responsive nanoprobe | Mild acidity | PAI | / | 43 |

| iNGR-lPNs@DOX | pH-responsive smart nanocarriers | Mild acidity | / | Chemotherapy | 46 |

| DOX@ZIF-8 | pH-responsive smart nanocarriers | Mild acidity | / | Chemotherapy | 47 |

| HA/Ara-IR820@ZIF-8 | pH-responsive smart nanocarriers | Mild acidity | FL | PDT/chemotherapy | 48 |

| PU/CAP | pH-responsive smart nanocarriers | Mild acidity | FL | Chemotherapy | 51 |

| AA-Azo-EG6 | pH-responsive smart nanocarriers | Mild acidity | / | Chemotherapy | 52 |

| PEG-PBLA-Ce6 | pH-responsive nanotheranostic agents | Mild acidity | MRI/FL | PDT | 54 |

| SPB@POM | pH-responsive nanotheranostic agents | Mild acidity | PAI | PTT | 55 |

| CyA-cRGD | GSH-responsive nanomedicine agents | GSH | FL | / | 63 |

| MnO2 nanosheets | GSH-responsive nanomedicine agents | GSH | FL/MRI | / | 64 |

| OEG-2S-SN38 | GSH-responsive smart nanocarriers | GSH | / | Chemotherapy | 68 |

| PEG/Mn-HMSNs | GSH/pH-responsive smart nanocarriers | GSH/mild acidity | MRI | Chemotherapy | 69 |

| MnMoOX-PEG | GSH-responsive nanotheranostic agents | GSH | MRI/PAI | PTT | 75 |

| Au@SiO2 | GSH-responsive nanotheranostic agents | GSH | MRI/PAI | PTT | 76 |

| PEG-PUSeSe-PEG | H2O2-responsive smart nanocarriers | H2O2/GSH | / | Chemotherapy | 86 |

| Ag@MSNs | H2O2-responsive smart nanocarriers | H2O2 | / | Chemotherapy | 87 |

| HAOPs | In situ O2 producer for improving PDT | H2O2 | / | PDT | 92 |

| PCN-224-Pt | In situ O2 producer for improving PDT | H2O2 | / | PDT | 93 |

| FeS2-PEG | H2O2 for chemodynamic therapy | H2O2 and mildly acidic | MRI | CDT | 96 |

| WO3-x@-poly-L-glutamic acid | H2O2 for chemodynamic therapy | H2O2 | PAI | PTT/CDT | 98 |

| MS@MnO2 NPs | H2O2 for chemodynamic therapy | H2O2/GSH | MRI | CDT | 99 |

| BODIPY | H2S-responsive smart nanoprobes | H2S | FL | / | 109 |

| NIR-II@Si | H2S-responsive smart nanoprobes | H2S | FL | / | 110 |

| Si@BODPA | H2S-responsive smart nanoprobes | H2S | PAI | / | 111 |

| Copper–zinc mixed MOF NP-1 | H2S-responsive theranostic agents | H2S | FL | PDT | 116 |

| Cu2O | H2S-responsive theranostic agents | H2S | PAI | PTT | 117 |

Abbreviations: CAP, cellulose acetate phthalate; CDT, chemodynamic therapy; FL, fluorescence imaging; GSH, glutathione; MOF, metal–organic framework; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NP, nanoparticle; PAI, photoacoustic imaging; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PTT, photothermal therapy; PU, polyurethane; DPP, diketopyrrolopyrrole; ZIF, Zeolitic imidazole frameworks; BPOx, benzo[ a ]phenoxazine; HAS, human serum albumin; DOX, doxorubicin; iNRG, CRNGRGPDC; Ara, Cytarabine; HA, hyaluronic acid; PU, polyurethane; AA, amino acid; Azo, azobenezene; EG6, oligoehtyleneglycol; PBLA, poly(β-benzyl-Laspartate); Ce6, chlorin e6; SPB@PON, semiconducting polymer brush and polyoxometalate cluster; CYA, cyanine; RGD, a tumor-targeting unit; OEG, oligo(ethylene glycol); SN38, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxyl-camptothecin; HMSNs, hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticals; MSNs, mesoporous silica nanoparticals; HAOP NP, H2O2-activatable and O2-evolving PDT nanoparticle; PCN-224, porous coordination network-224; MS, mesoporous silica; BODIPY, boron dipyrromethene; NIR‐II, the second near‐infrared window; BODPA, semi-cyanine-BODIPY hybrid dyes.

pH-responsive nanomedicine agents

In tumor tissues, because the growth rate of tumor cells is usually much faster than that of normal cells, the existing nutrients and blood oxygen content cannot meet the growth needs.32 As a result, tumor cells produce energy for survival through anaerobic glycolysis, which is different from that of oxidative phosphorylation for normal cells. With such metabolisms, tumor cells would generate a large amount of lactic acid and adenosine triphosphate hydrolysate, as well as some excess carbon dioxide and protons, which results in increased acidity of the tumor site and lower pH value than that of normal tissue.33 Generally, the pH value in the normal human tissue cells and normal cell lysosomes is about 7.4 and 5.0–6.5, respectively, while that of the tumor tissue and tumor cell lysosomes is about 6.0–7.0 and 4.0–5.0, respectively.34 To explore this special acidic TME for improving tumor diagnosis and treatment, a number of pH-sensitive nanomedicine agents have been developed.35

pH-responsive smart nanoprobes

Many researchers have utilized the difference pH between tumor tissue and normal tissue to design smart nanoprobes, which display significantly different/varying signals in these two tissues, giving a high diagnosis signal-to-noise ratio.36,37 To date, a number of pH-responsive smart nanoprobes have been explored on the basis of various imaging techniques, including fluorescence imaging,38 photoacoustic imaging,39 and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).40 For instance, Liu et al41 designed a pH-responsive nanoassembly based on DPP-thiophene-4 (diketopyrrolopyrrole) for fluorescent images of numbers of different malignant tumors (Figure 1A). With pH>7.0, the fluorescence molecules of DPP-thiophene-4 (diketopyrrolopyrrole) self-assemble into nanoassemblies with very weak fluorescent emission, while when the pH is lower than 6.8 the assemblies disassemble into individual fluorescence molecules, associating with strong fluorescent emission, as shown in Figure 1B. Besides, with every 0.2 pH unit change, the signal of fluorescent emission increased by about 10-fold, which makes this pH-responsive nanoassembly a promising probe for precisely imaging different malignant tumors in vivo (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of the pH-switchable DPP-thiophene-4-based probe for fluorescence imaging of malignant tumor. (B) TEM images of DPP-thiophene-4 at either pH 6.8 or 7.0. (C) Fluorescence imaging and corresponding signal changes of six malignant tumor-bearing mice before and after injection of DPP-thiophene-4 (10 μg/mL) at tumor tissue (red dotted cycle) and nontumor area (blue dotted cycle). Figures A to C reprinted with permission from Liu Y, Qu Z, Cao H, et al. pH switchable nanoassembly for imaging a broad range of malignant tumors. ACS Nano. 2017; 11(12):12446–12452.41 Copyright © 2017, American Chemical Society. (D) Illustration of the Fe3O4-ZIF-8 assembly as pH and glutathione (GSH)-responsive T2–T1 switching magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent. (E) Relaxivity of Fe3O4@ZIF-8 after incubation with different pH and concentrations of GSH in PBS for 3 h. (F) In vivo T1 MRI images and (G) corresponding T1 signals of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice before and after intravenous injection of Fe3O4@ZIF-8. Figures D to G are reprinted with permission from Lin J, Xin P, An L, et al. Fe3O4-ZIF-8 assemblies as pH and glutathione responsive T2–T1 switching magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent for sensitive tumor imaging in vivo. Chem Commun. 2019;55(4):478–481.42 Copyright © 2019, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Abbreviations: DPP, diketopyrrolopyrrole; ZIF, Zeolitic imidazole frameworks; GSH, glutathione.

Lin et al42 developed a pH and GSH-responsive T2–T1 switching MRI contrast agent (Fe3O4-ZIF-8 assembly) for highly sensitive tumor imaging (Figure 1D). The Fe3O4-ZIF-8 assembly was built using the zeolitic-imidazole framework (ZIF-8) as a matrix to assemble the small Fe3O4 nanoparticles (T1 contrast agent) into Fe3O4 aggregation (T2 contrast agent). In the acidic environment and the presence of GSH, the ZIF-8 matrix is unstable, resulting in disassembly of the Fe3O4-ZIF-8 assembly and release of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, consequently leading to the T2–T1 switching contrast (Figure 1E). In vivo T1-weighted images of mice-bearing 4T1 tumor showed that Fe3O4@ZIF-8 was able to provide darkening contrast enhancement for the liver site and darkening to brightening contrast enhancement for the tumor site (Figure 1F and G), giving remarkably different MRI signals for improving the distinction between normal tissue and tumor tissue.

Using the ratio method or code equation to analyze the imaging signal of the responsive probe at different pH, correspondence between the imaging signal and the pH value can be established, which can in turn be used to detect the tumor pH in real time. For example, Chen et al43 reported a pH-responsive nanoprobe (C–HSA–BOPx–IR825) for detecting the pH of the TME. The nanoprobe was designed on the basis of the pH-inert NIR dye IR-825 (as internal reference) and the pH-responsive NIR dye benzo[a]phenoxazine (BOPx, as indicator) with photoacoustic imaging analysis; the ratios of signal intensity for C–HSA–BOPx–IR825 at 680 nm (from BOPx) and 825 nm (from IR825) were decreased with the increase of pH value, and exhibited a linear relationship in the pH range of 4.5–7.0, making this nanoprobe have great potential for application in the detection of tumor pH.

pH-responsive smart nanocarriers

Because traditional molecule antitumor drugs have significant side effects for normal organs, enormous interest has been focused on the development of a smart nanocarrier that can deliver and control the release of molecular drug.44 The low pH value of the TME makes it possible to design a pH-responsive smart nanocarrier for tumor-specific chemotherapy. Theoretically, a pH-sensitive nanocarrier would deliver and control the release of the antitumor drug upon encountering the acid microenvironment of tumor, while exhibiting very low or zero drug release in the normal tissue, thus reducing the damage to normal tissue during treatment.45 Ye et al46 designed a pH-sensitive lipid-polypeptide hybrid nanoparticle (iNGR-lPNs) loaded with the antitumor drug doxorubicin (DOX) to address cellular uptake and intracellular drug release for tumor treatment. Likely a pH-sensitive switch, this smart nanoparticle undergoes a first phase transition at pH 7.0–6.5 with the surface potential transformed from negative charge to neutral charge for increasing cellular uptake, and a second phase transition at pH 6.5–4.5 with disassembly of the skeleton to induce endolysosome escape and release the DOX into the cytoplasm. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that this two-step pH-responsive delivery can promote cell uptake and control the release of drug in the acidic environment, consequently leading to more potent antitumor efficacy and less systemic toxicity.

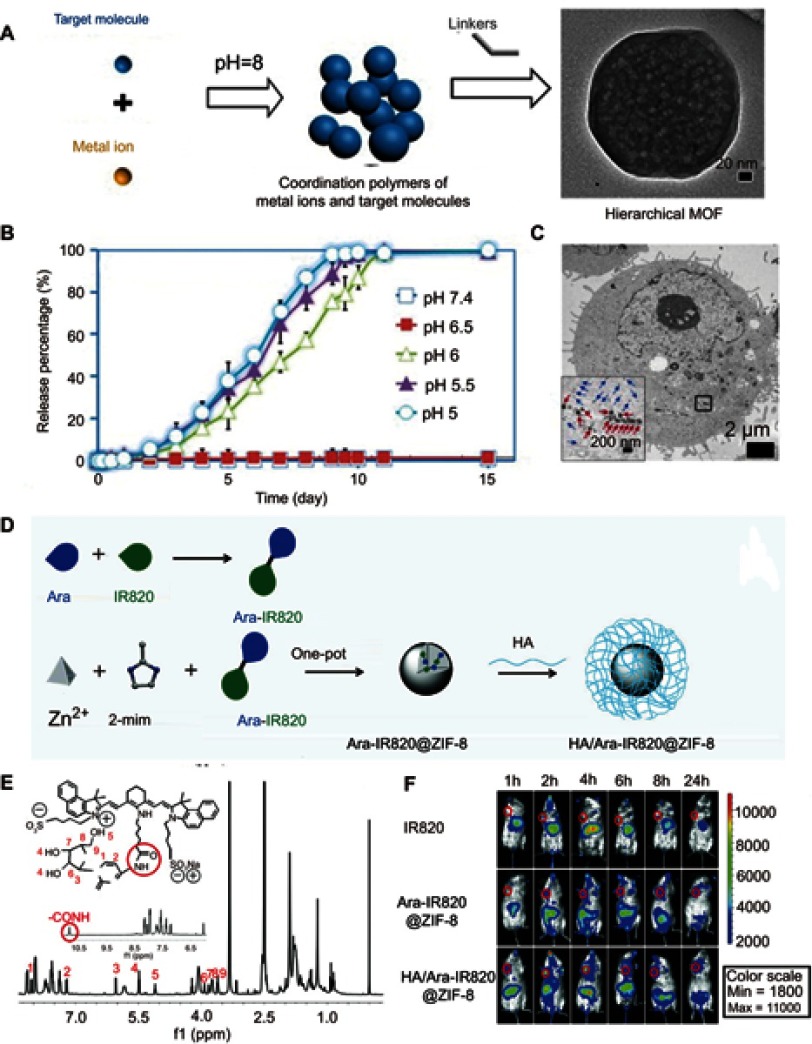

For the design of smart nanocarriers, metal–organic frameworks have attracted great attention because of their designable structures and unique porous frameworks for high drug loading. Zhou et al reported one-pot synthesis of a metal–organic framework (ZIF-8) with high encapsulation of DOX (Figure 2A).47 Because the ZIF-8 is stable in the neutral condition, but decomposes in the acid environment, the release of DOX molecules that loaded in the ZIF-8 matrix can be controlled by pH (Figure 2B and C). Zhang et al48 developed a versatile prodrug strategy to further increase the amount of drug loading within the pH-responsive metal–organic framework carrier (ZIF-8) (Figure 2D). As a proof of concept, a drug molecule (cytarabine, Ara) was bonded to a fluorescence molecule (indocyanine green, Ara-IR820) to form a prodrug Ara-IR820 (Figure 2E), which was then embedded into the ZIF-8 matrix (Ara-IR820@ZIF-8) with high loading owing to the strong interaction between sulfonic groups (from IR820) and ZIF-8. At the same time, a tumor targeting molecular HA was bound to the ZIF-8 to improve the tumor targeting ability. Upon entering the tumor tissues/cells, the low pH triggered the HA/Ara-IR820@ZIF-8 to disassemble and release Ara-IR820, which subsequently hydrolyzed (the amide bond) to form the individual molecule of IR820 for fluorescence imaging and Ara for chemotherapy. In vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that this pH-sensitive HA/Ara-IR820@ZIF-8 with good tumor targeting capability exhibited excellent pH-triggered fluorescence imaging-guided chemotherapy and photodynamic dual treatment against cancers (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic illustration of the pH-induced one-pot fabrication of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) with encapsulated target molecules. (B) Release profiles of doxorubicin (DOX) from DOX@ZIF-8 trigged by different pH. (C) TEM image of an MDA-MB-468 cell incubated with DOX@ZIF-8. Figures A to C reprinted with permission from Zheng H, Zhang Y, Liu L, et al. One-pot synthesis of metal–organic frameworks with encapsulated target molecules and their applications for controlled drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(3):962–968.47 Copyright © 2016, American Chemical Society. (D) Schematic illustration of the construction of prodrug-loaded HA/Ara-IR820@ZIF-8. (E) 1H NMR spectra of the synthesized prodrug Ara-IR820 in DMSO-d6. (F) Fluorescence imaging of the tumor-bearing mice at different times after intravenous injection with IR820, Ara-IR820@ZIF-8, and HA/Ara-IR820@ZIF-8, respectively. Figures D to F reprinted with permission from Zhang H, Li Q, Liu R, et al. A versatile prodrug strategy to in situ encapsulate drugs in MOF nanocarriers: a case of cytarabine-IR820 prodrug encapsulated ZIF-8 toward chemo-photothermal therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(35):1802830.48 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; ZIF, Zeolitic imidazole frameworks; Ara, Cytarabine; HA , hyaluronic acid; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Because of their unique viscoelastic and biomimetic properties, hydrogels assembled by small-molecular or polymeric networks/fibers are also promising materials for designing smart drug delivery.49,50 For instance, Hua et al51 designed pH-responsive core-hell nanofibers for intravaginal drug delivery. The core-hell nanofibers composed of polyurethane (PU) and cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) exhibited significantly improved tensile strength compared with the existing CAP. These coaxial fibers were stable in the acidic environment (pH 4.2), while dissolving very rapidly in the neutral environment and released the loading rhodamine fluorescent molecules. Besides, they exhibited low cytotoxicity, giving great potential for use as pH-responsive drug delivery. Xiong et al52 reported a novel multiresponsive hydrogel assembled by an amine acid gelator AA-Azo-EG6. Owing to the coexistence of different functional groups (including amino acid head, azobenzene, and oligoethylene glycol), this hydrogel has responsive behavior upon triggering by pH, ultraviolet–visible light, and temperature, showing great potential use in tissue engineering and drug delivery.

pH-responsive nanotheranostic agents

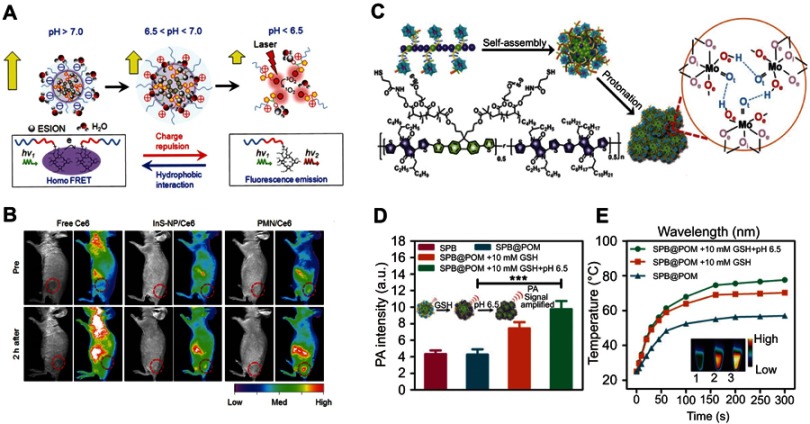

By utilizing the low pH in the TME, it is possible to design smart nanodiagnostic agents with diagnosis and treat functions simultaneously activated by the change of pH values.53 For example, Ling et al54 developed a pH-responsive magnetic nanotherapeutic agent (termed pH-sensitive magnetic nanogrenades, PMNs) for MRI imaging and fluorescence imaging guiding photodynamic therapy of resistant heterogenous tumors (Figure 3A). This nanotherapeutic agent was built by self-assembly of Ce6-grafted-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(β-benzyl-L-aspartate) (PEG-PBLA-Ce6) and ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles. In a neutral environment (pH 7.4), the surface charge of the PMN is negative, and the Ce6 encapsulated in the PMN loses its fluorescence because of the fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Once it reaches a slightly acidic environment, the whole body of the PMN becomes positively charged and expands to promote cell uptake. When the pH is below 6.5, excessive H+ in the solution causes the monomers in the PMN to repel each other, leading to cracking of the PMN and the release of iron oxide nanoparticles for T1-weighted contrast and Ce6 for fluorescent imaging and generation of 1O2. In vivo experiments with colon cancer tumors have shown that PMNs exhibited excellent activated dual-mode imaging and photodynamic therapy effects (Figure 3B), demonstrating that such pH-responsive PMNs have great potential for early tumor detection and specific treatment.

Figure 3.

(A) pH-induced structural transformation of pH-sensitive magnetic nanogrenades (PMNs) and change of magnetism and photoactivity. (B) In vivo near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent imaging of HCT116 tumor-bearing mice before and after intravenous injection of different materials. Figures A and B reprinted with permission from Ling D, Park W, Park SJ, et al. Multifunctional tumor pH-sensitive self-assembled nanoparticles for bimodal imaging and treatment of resistant heterogeneous tumors. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(15):5647–5655.54 Copyright © 2014, American Chemical Society. (C) Schematic of the structure of semiconducting polymer brush (SPB), and fabrication of SPB@POM, as well as mechanism for the acidity-triggered aggregation of SPB@POM. (D) Photoacoustic intensities of SPB and SPB@POM under different conditions. (E) Time-dependent temperature rise curves and IR thermal image (insets) for SPB@POM under different conditions. Figures C to E reprinted with permission from Yang Z, Fan W, Tang W, et al. Near-infrared semiconducting polymer brush and pH/GSH-responsive polyoxometalate cluster hybrid platform for enhanced tumor-specific phototheranostics. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2018; 57(43):14101–14105.55 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; PMNs, pH sensitive magnetic nanogrenades; SPB@PON, semiconducting polymer brush and polyoxometalate cluster.

Yang et al55 designed an acidity/reducibility dual-responsive assembly (SPB@POM) contained a semiconducting polymer brush (SPB) and a polyoxometalate cluster (POM) (Figure 3C). In the acidic microenvironment, the small assembly will self-assemble into big aggregate through proton-induced hydrogen bonding self-assembly. This self-assembly could not only enhance the retention and accumulation of assembly in the tumor, but also enhance the NIR absorption of the assembly, consequently leading to remarkable improvement in the contrast of photoacoustic imaging and the efficacy of photothermal therapy (Figure 3D and E). Yang et al56 chose to combine pH-sensitive polyaniline polymer with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to synthesize a biocompatible pH-responsive agent for photothermal therapy of tumors. In a neutral environment, polyaniline with the structure of an emeralidine base exhibited the main absorbance peak at about 580 nm, while in the acidic environment its structure was changed to emeralidine salt with absorbance red-shifted to the NIR region, which could be used as NIR photothermal therapy.

GSH-responsive nanomedicine agents

Due to the different potential between the internal and external environments of tumor cells, tumor cells can overproduce some reducing substances.57 One of the typical overexpressed reducing substances is GSH.58 Generally, the concentration of GSH in tumor cytoplasm can reach 2–10 mmol/L,59 which is 100–1000 times higher than that of the extracellular fluid and blood. Therefore, GSH has been identified as an ideal stimulating element for designing tumor-specific smart nanomedicine agents.

GSH-responsive smart nanoprobes

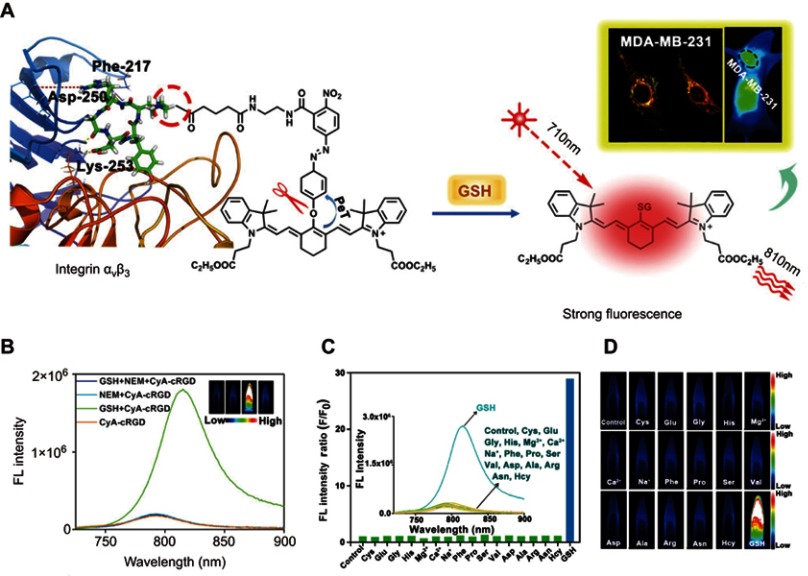

For the design of a GSH-responsive organic molecule probe or nanoprobe, several reducible bonds, including the disulfide bond,60 diselenium bond,61 and nitroazo-aryl-ether,62 have attracted great attention. In the presence of GSH, these reducible bonds can be cleaved, thus leading to the activation of the probe. For example, Yuan et al63 reported a GSH turn-on NIR fluorescent probe (CyA-cRGD), composed of a NIR fluorescence unit (CyA) binding with a fluorescence quenching unit (nitroazo aryl ether group) and a tumor-targeting unit (cRGD) (Figure 4A). With the presence of GSH, the nitroazo aryl ether group connecting the fluorescence unit and the fluorescence quenching unit will be cleaved, leading to the turn-on of the fluorescence (Figure 4B). Competition experiments revealed that this GSH-responsive CyA-cRGD probe has high selectivity along different amino acids and metal ions (Figure 4C and D). Moreover, with excellent tumor targeting capability, this probe displays a high fluorescence signal-to-noise ratio for distinguishing the tumor tissue and normal tissue, making it highly promising for application in early tumor diagnosis.

Figure 4.

(A) Proposed glutathione (GSH)-mediated activation mechanism of CyA-cRGD probe. (B) Fluorescence spectra of CyA-cRGD probe with and without NEM or GSH. (C) Relative fluorescence (FL) intensity ratios of CyA-cRGD in the presence of different amino acids or metal ions. (D) Fluorescence images of CyA-cRGD in the presence of different amino acids and metal ions detected by the near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging system. Figures A to D reprinted with permission from Yuan Z, Gui L, Zheng J, et al. GSH-activated light-up near-infrared fluorescent probe with high affinity to αvβ3 integrin for precise early tumor identification. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(37):30994–31007.63 Copyright © 2018, American Chemical Society.

Abbreviations: CYA, cyanine; RGD, a tumor-targeting unit; GSH, glutathione.

Besides organic materials, many inorganic materials, such as MnO2, gold nanoparticles, and polyoxometalate cluster, have also been widely used for designing GSH-responsive nanoprobes. For instance, Yuan et al64 developed a GSH-responsive probe combining fluorescence and MRI dual imaging on the basis of MnO2 nanosheets. The fluorescence unit of aptamer was bound to the MnO2 nanosheets, which serves as a fluorescence quencher. Upon endocytosing by tumor cells, the MnO2 nanosheets react with the overexpressed GSH to generate abundant Mn2+ ions and release the primers, consequently leading to simultaneousl turn-on of the signals for MRI and fluorescence imaging, which in turn can be used to detect the cellular GSH.

GSH-responsive smart nanocarriers

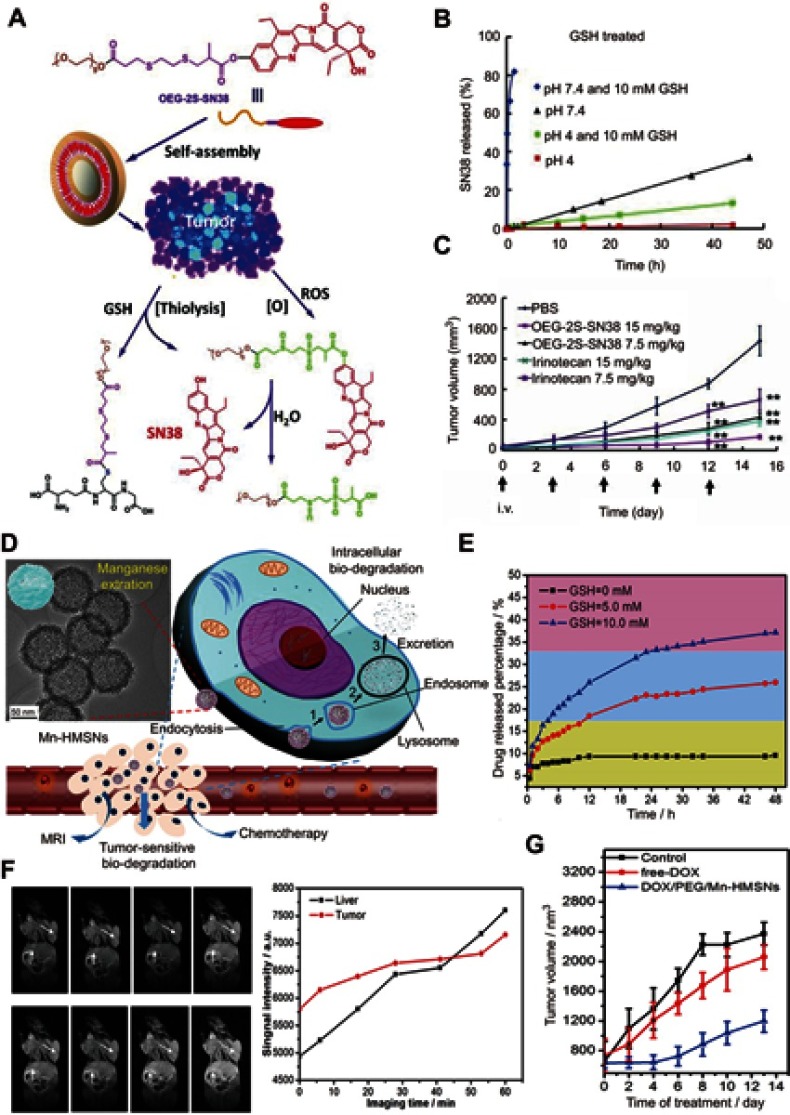

For the design of GSH-responsive drug nanocarriers, two common strategies have been widely used. The first strategy is directly connecting the drug molecule to another molecule or polymer through clearable bonds (such as a disulfide bond), and then self-assembly into a nanoparticle or lipidosome.65 The second strategy is loading the drug molecule into GSH-responsive or non-GSH-responsive porous matrixes such as mesoporous silicon and metal–organic frameworks.66 For the porous matrixes without GSH-responsive ability, their aperture can be sealed after the adsorption of the drug using small molecules that contain clearable bonds or using nanoparticles that can be degraded by GSH.67 For example, Wang et al68 designed a GSH and ROS heterogeneity-responsive prodrug nanocapsule (OEG-2S-SN38) through self-assembly of a polymer, composed of a chemotherapy drug SN38 and an oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) chain linked by a thioether chain with ester groups (Figure 5A). Upon encountering GSH/ROS, the nanoparticle would be disassembled owing to the thiolysis triggered by GSH (Figure 5B) and enhanced hydrolysis of the linker triggered by the ROX oxidation, leading to the release of the parent drug SN38 for anticancer therapy (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

(A) The self-assembly and redox triggered the SN38 releasing mechanism of the OEG-2S-SN38 nanocapsule. (B) SN38 releasing curves in PBS with or without glutathione (GSH) (10 mM) at pH 7.4 or 4 at 37 °C. (C) The changes of tumor volume for different treatment groups. Figures A to C reprinted with permission from Wang J, Sun X, Mao W, et al. Tumor redox heterogeneity-responsive prodrug nanocapsules for cancer chemotherapy. Adv Mater. 2013;25(27):3670–3676.68 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. (D) Schematic illustration of the GSH/acid-responsive polyethylene glycol (PEG)/Mn-HMSN drug carrier designed through a “manganese extraction” strategy for enhancing theranostic functions. (E) Accumulated releasing curves of Mn elements in the neutral SBF with GSH concentrations of 0, 5.0, and 10.0 mM. (F) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of tumor-bearing mice and corresponding T1 signal intensity of the tumor and liver sites before and after intravenous injection of PEG/Mn-HMSNs with a dose of 5 mg/kg. (G) Tumor-growth inhibition effect for different treatment groups. Figures D to G reprinted with permission from Yu L, Chen Y, Wu M, et al. “Manganese extraction” strategy enables tumor-sensitive biodegradability and theranostics of nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2016; 138(31):9881–9894.69 Copyright © 2016, American Chemical Society.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; i.v., intravenous; OEG, oligo(ethylene glycol); SN38, 7-ethyl-10-hydroxyl-camptothecin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; GSH, glutathione; HMSNs, Hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticals; PEG, polyethylene glycol; MR, magnetic resonance.

Recently, Yu et al69 reported a “manganese extraction” strategy for design of GSH/acid-responsive mesoporous silica drug carrier (PEG/Mn-HMSNs) with good biodegradation and theranostic functions (Figure 5D). The doping of Mn ions into the mesoporous silica means the introduction of the –Mn–O– bonds into the –Si–O–Si– skeleton. Because –Mn–O– bonds can be easily broken in the reducing or acidic conditions, the –Mn–O– bond-doped skeleton of the mesoporous silica exhibited fast disintegration and biodegradation in the TME (Figure 5E). Besides, the degradation of the Mn-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticles trigged by GSH led to activation of the release of abundant Mn2+ ions for MRI and drug for chemotherapy (Figure 5F and G).

GSH-responsive nanotheranostic agents

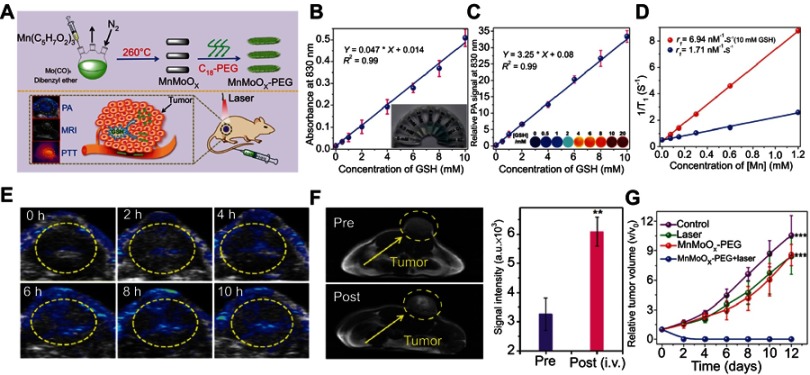

Besides smart probes and drug carriers, the design of GSH-responsive smart nanotheranostic agents that combine both functions of diagnosis and therapy is also a hot research topic in the field of nanomaterial and nanomedicine.70 To date, many kinds of nanomaterials, including organic polymer,71 metal oxide,72 gold nanoparticles,73 and polyoxometalate clusters,74 have been utilized to design GSH-responsive nanotheranostic agents. For example, Gong et al75 successfully synthesized a bimetallic oxide MnMoOX nanorod as a GSH-responsive smart nanotheranostic agent (Figure 6A). The original PEG-modified MnMoOX nanorods exhibited almost no NIR absorption. However, once interacted with GSH, the MoVI ions in MnMoOx were reduced to MoV ions, making the nanorods possess strong NIR absorption that can be utilized for photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy (Figure 6B and C). Besides, the change of the charge of Mn ions leads to increased r1 relaxivity with improved MRI (Figure 6D). In vivo experiments demonstrated that this MnMoOX nanorod possessed good biodegradability and excellent GSH-triggered photoacoustic imaging and MRI for guiding photothermal therapy (Figure 6E–G).

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of the glutathione (GSH)-responsive MnMoOX nanorod for tumor theranostic application. (B) Ultraviolet–visible absorption spectra and (C) PA signal intensities of MnMoOX-PEG after incubation with different concentrations of GSH. (D) T1 relaxation rates of different concentrations of MnMoOX-PEG before and after incubation with 10 mM GSH. (E) In vivo photoacoustic imaging of tumors, and (F) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of tumor-bearing mice and corresponding T1 signal intensity of the tumor sites before and after intravenous injection of MnMoOX-PEG. (G) Tumor growth curves of mice for different treatment groups. Figures A to G reprinted with permission from Gong F, Cheng L, Yang N, et al. Bimetallic oxide MnMoOX nanorods for in vivo photoacoustic imaging of GSH and tumorspecific photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 2018;18(9):6037–6044.75 Copyright © 2018, American Chemical Society.

Abbreviations: i.v., intravenous; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PTT, photothermal therapy; GSH, glutathione; PA, photoacoustic.

Recently, Liu et al76 designed a GSH-responsive magnetic gold nanowreath by layer-by-layer self-assembly of gold nanowreath-coated SiO2 with small magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. In the TME, the overproduced GSH would trigger disassembly of iron oxide nanoparticles, resulting in turn-on of T1-weighted MRI for determining the best time point for therapy. Besides, the gold nanowreath in this agent also endows it with excellent functions of photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy of tumor. Therefore, combining turn-on T1 contrast imaging and innate photoacoustic imaging can effectively guide photothermal therapy.

H2O2-responsive nanomedicine agents

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is another overproducing metabolite in most common tumors.77 Accumulating evidence suggests that H2O2 in normal tissues is usually at a low level, while that in the tumor tissues is much higher at 100 μM–1 mM,78 which may attributed to the overproduction of oxide dismutase (SOD) for catalyzing the conversion of superoxide anion radicals to H2O2 and O2.79–81 An increased level of H2O2 may play a significant role, directly or indirectly, in the development of the cancer cells, but can also induce apoptosis of cancer cells when increased to a much higher level. For chemists, the characteristic high level of H2O2 for the tumor environment can be explored to design H2O2-responsive drug carriers,77 endogenous O2 producers,82 and chemodynamic therapy agents83 for tumor-specific diagnosis and treatment.84

H2O2-responsive smart nanocarriers

For the design of H2O2-responsive drug nanocarriers, oxidation-responsive polymers have attracted considerable attention. For example, poly(propylene sulfide) is a hydrophobic polymer, but it can transform to a hydrophilic polymer (poly(propylene sulfphone)) upon oxidative conversion.85 The hydrophobic poly(propylene sulfide) can self-assemble into nanoparticles with a hydrophilic block such as poly(ethylene glycol) and a hydrophobic drug molecule such as DOX. Upon encountering H2O2, the hydrophobic poly(propylene sulfide) would be oxidized into hydrophilic poly(propylene sulfphone), resulting in disassembly of the nanoparticles and release of the DOX molecule for chemotherapy.

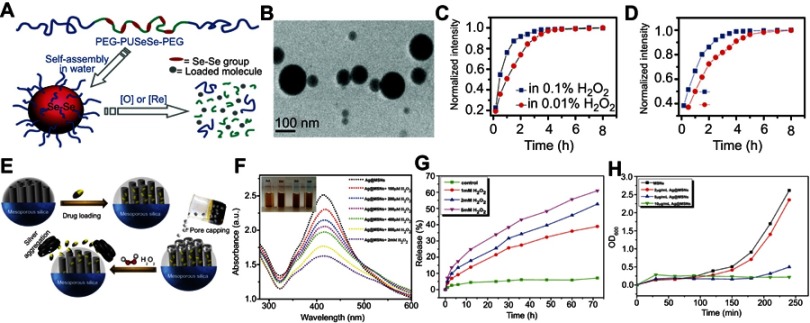

Ma et al86 reported a redox dual-responsive assembly containing diselenide block copolymers as a potential drug carrier (Figure 7A). The diselenide bonds (Se–Se) in the block copolymers can be cleaved and oxidized into seleninic acid in the oxidation environment and reduced into selenol in the presence of reductants. Therefore, the micelles formed by such diselenide block copolymers will disassemble upon encountering oxidants such as H2O2 or reductants such as GSH, and simultaneously release the cargo loading in the micelles (Figure 7B–D).

Figure 7.

(A) Schematic illustration of the redox-trigged disassembly of PEG-PUSeSe-PEG micelles. (B) Cryo-TEM image of PEG-PUSeSe-PEG micelles. Releasing profiles of rhodamine B from PEG-PUSeSe-PEG micelles triggered by (C) H2O2 and (D) glutathione. Reproduced with permission. Figures A to D reprinted with permission from Ma N, Li Y, Xu H, et al. Dual redox responsive assemblies formed from diselenide block copolymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2010; 132(2):442–443.86 Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society. Copyright © 2010, American Chemical Society. (E) Schematic illustration of the synthetic procedure and H2O2-triggered drug release from Ag@MSN carrier. (F) Absorbance spectra of Ag@MSNs in the presence of various concentrations of H2O2. (G) Releasing profiles of ibuprofen from Ag@IBU@MSNs in the presence and absence of H2O2. (H) Growth profiles of bacteria in LB media with different concentrations of Ag@MSNs. Figures E to H reprinted with permission from Muhammad F, Wang A, Miao L, et al. Synthesis of oxidant prone nanosilver to develop H2O2 responsive drug delivery system. Langmuir. 2015;31(1):514–521.87 Copyright © 2014, American Chemical Society.

Abbreviations: PEG, polyethylene glycol; PU, polyurethane; Se-Se, diselenide bonds; MSNs, mesoporous silica nanoparticals.

Besides blocking copolymer micelles, porous materials such as mesoporous silica have also been widely utilized to design H2O2-responsive drug carriers. Using H2O2-responsive ultrasmall Ag nanoparticles as nanolids for sealing the drug in the channel of mesoporous silica nanoparticles, Muhammad et al87 developed a H2O2-responsive silica-based drug delivery system (Figure 7E). In the TME, overexpressed H2O2 triggered the Ag nanoparticles to leave from the cap of the channel of mesoporous silica and to aggregate, followed by release of the therapeutic drug (Figure 7F–H).

In situ O2 producer for improving photodynamic therapy

Hypoxia is a state referring to the low level of oxygen, which is a typical characteristic of most solid tumors.88 The origins of tumor hypoxia can be mainly traced to abnormal vascularization raised by the fast growth of the tumor. Compared with the normal cells that have an oxygen concentration of about 2–9%, the oxygen concentration of the TME is usually down to about 0.02–2%.89 The hypoxia not only provides an environment that is beneficial for the spread of the cancer stem cells, but also increases the multidrug-resistant proteins and decreases the therapeutic efficacy of many anticancer drugs and oxygen-dependent invasive therapy, such as photodynamic therapy.81 To date, a number of strategies have been used to increase the concentration of oxygen in the tumor tissue, including directly delivering oxygen by nanocarriers, and in situ catalysis of the decomposition of H2O2 to generate O2.

With the presence of a catalyst, such as natural catalase,83 MnO2,90 or Pt and Au nanoparticles,91 the overproduced H2O2 in the tumor site can be utilized as an in situ O2 generator for improving the efficacy of photodynamic therapy. For example, Chen et al92 reported a PDT nanoparticle that activated H2O2 and continuously generated O2 for efficient hypoxic tumor therapy (Figure 8A). This nanoparticle was self-assembled by PLGA, combined with methylene blue as photosensitizer, catalase as H2O2 catalyst, black hole quencher-3 as quencher of the photosensitizer, and RGDfK as tumor targeting ligand. Upon being taken up by the tumor cells, the H2O2 would penetrate into the core of the nanoparticle and self-decompose to generate O2 under catalysis by catalase. The generated O2 would trigger the crack of the nanoparticles, followed by the release of the photosensitizer (Figure 8B). Upon irradiation by a 635-nm laser, the released photosensitizer can generate sufficient 1O2 to effectively destroy the cancer cells owing to the self-sufficiency of O2 in the hypoxia tumor site (Figure 8C and D). Therefore, this design not only uses H2O2 as a trigger for activating the generation of 1O2 with high region selectivity, but also as an O2 generator for improving the efficacy of photodynamic therapy in the hypoxia tumor.

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic illustration of the mechanism of H2O2-triggered O2 generation and photosensitizer release for enhanced photodynamic therapy (PDT). (B) Releasing curves for MB from HAOP nanoparticles (NPs) with and without H2O2 (100 μM). (C) Tumor growth curves of mice upon different treatments. (D) H&E staining of tumors for different groups at 24 h post treatment. Figures A to D reprinted with permission from Chen H, Tian J, He W, et al. H2O2-activatable and O2-evolving nanoparticles for highly efficient and selective photodynamic therapy against hypoxic tumor cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(4):1539–1547.92 Copyright © 2015, American Chemical Society. (E) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of PCN-224-Pt. (F) Ultraviolet–visible spectra of remainding H2O2 after catalysis by PCN-224-Pt for different times at pH 7.4. (G) Degradation rates of DPBF after treatment with PCN-224 or PCN-224-Pt in the absence and presence of H2O2 under light irradiation in a N2 atmosphere at pH 7.4. (H) Photographs of mice bearing H22 tumor before and on day 14 after various treatments. (I) Relative tumor volume for different treatment groups. Figures E to I reprinted with permission from Zhang Y, Wang F, Liu C, et al. Nanozyme decorated metal–organic frameworks for enhanced photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12(1):651–661.93 Copyright © 2018, American Chemical Society.

With Pt nanoparticles as nanozymes, and a porphyrin based metal–organic framework (PCN-224) as photosensitizer, Zhang et al93 reported a versatile strategy for enhanced photodynamic therapy in the hypoxia tumor (Figure 8E). The Pt nanoparticles decoded on the PCN-224 can effectively catalyze the decomposition of endogenous H2O2 to continuously generate O2 for PCN-224 to transform into 1O2 under laser irradiation (Figure 8F and G). As a result, this PCN-224-Pt photosensitizer exhibited much better photodynamic therapy efficacy in both in vitro and in vivo therapy experiments, as compared with that of PCN-224 (Figure 8H and I).

H2O2 for chemodynamic therapy

Besides as an O2 producer, utilizing the overproduction of H2O2 in the tumor site to trigger chemodynamic therapy has also recently received tremendous interest. Chemodynamic therapy is an emerging therapeutic strategy using the hydrogen radical (OH), generated through the Fenton reaction or a Fenton-like reaction in the presence of Fenton agents and H2O2, as a toxic reactive oxygen species to kill tumor cells.94 This therapeutic strategy was recently proposed by Bu et al.45 Because it is activated via two endogenous stimulating elements, including sufficient H2O2 and mildly acidic conditions (to dissolve ferrous ions from the nanomaterials), chemodynamic therapy has advantages of high logicality and selectivity, as compared with many other therapy methods such as chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and radiotherapy. Up to now, a number of inorganic and inorganic–organic hybrid nanomaterials, including Fe3O4,95 FeS2,96 and Cu/Fe complex nanoparticles,97 have been explored as H2O2 catalysts for chemodynamic therapy on the basic principles of the Fenton reaction.

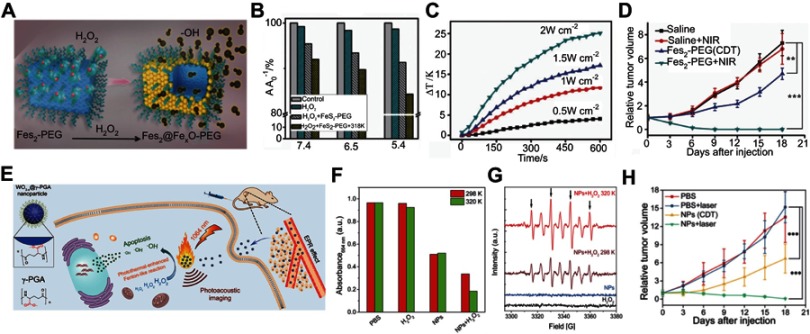

Utilizing the high content of H2O2 in the tumor, Tang et al96 designed an antiferromagnetic pyrite nanocube decorated with polyethylene glycol (FeS2-PEG) for self-enhanced MRI and chemodynamic therapy. In the tumor site, the FeS2-PEG catalyzed the endogenous H2O2 to generate OH effectively through the Fenton reaction (Figure 9A). Besides, the localized heat from the photothermal properties of the pyrite can accelerate the Fenton reaction, making it more effective for chemodynamic therapy (Figure 9B and C). Furthermore, upon surface oxidation by H2O2, the valence state of the ferrous ion was changed, leading to enhancement of the T1 and T2 MRI signals for guiding chemodynamic therapy (Figure 9D).

Figure 9.

(A) Schematic illustration of H2O2-triggered surface oxidation of FeS2-PEG with the generation of OH. (B) MB decolorization for investigating the efficiency of the Fenton reaction under different experimental conditions. (C) Temperature curve upon irradiation by different laser intensities. (D) Relative tumor volume change after different treatments. Figures A to D reprinted with permission from Tang Z, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. Antiferromagnetic pyrite as the tumor microenvironment-mediated nanoplatform for self-enhanced tumor imaging and therapy. Adv Mater. 2017;29(47):1701683.96 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. (E) Mechanism of the photoacoustic imaging guiding photothermal-enhanced chemodynamic therapy. (F) MB absorbance for evaluating the efficiency of Fenton-like reaction under various conditions. (G) ESR spectra with different experimental conditions. (H) Change of relative tumor volume after different treatments. Figures E to H reprinted with permission from Liu P, Wang Y, An L, et al. Ultrasmall WO3–x@γ-poly-l-glutamic acid nanoparticles as a photoacoustic imaging and effective photothermal-enhanced chemodynamic therapy agent for cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(45):38833–38844.98 Copyright © 2018, American Chemical Society.

Abbreviations: CDT, chemodynamic therapy; NIR, near-infrared; NP, nanoparticle; PEG, polythylene glycol; MB, Methylene blue; ESR, Electron spin resonance.

Liu et al98 reported photothermal-enhanced chemodynamic therapy using ultrasmall WO3-x@-poly-L-glutamic acid nanoparticles (Figure 9E).98 Upon encountering H2O2, the WO3-x@-poly-L-glutamic acid nanoparticles exhibit a Fenton-like reaction to generate OH, and the generated rate can be effectively enhanced by increasing the surrounding reaction temperature through effective photothermal conversion (Figure 9F and G). Besides, the good photoacoustic performance can be used to guide this synergistic treatment (Figure 9H), making WO3-x@-poly-L-glutamic acid nanoparticles promising H2O2-responsive theranostic agents.

In the TME, there is not only H2O2 but also a large amount of the reducing substance GSH, which can significantly deteriorate the diagnosis and treatment effect of H2O2-responsive theranostic agents. To overcome this obstacle, Lin et al99 designed a MnO2-based nanoagent with simultaneous Fenton-like Mn2+ ion delivery and GSH depletion for enhanced chemodynamic therapy. After being taken up by cancer cells, the MnO2 decorating the mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MS@MnO2 NPs) reacts with the GSH in the acidic TME to generate glutathione disulfide and Mn2+ ions. The resulting Mn2+ ions serve as Fenton-like ions to trigger the H2O2 to form OH for killing cancer cells, and simultaneously as activity T1-weighted contrast agents for MRI. The properties of simultaneous acid-controlled Mn2+ ionrelease and GSH depletion endow MS@MnO2 NPs with intensified chemodynamic therapy and activatable MRI functions for monitoring therapy, demonstrating the great potential of MnO2 as a TME-responsive multifunctional theranostic agent.

H2S responsiveness

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a key signal molecule in the human body and plays an important role in health and disease.100,101 Accordingly, in mammalian systems, endogenous H2S is primarily synthesized from cysteine or cysteine derivatives in the presence of enzyme catalyst, such as cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate thiotransferase (3-MST).102–104 It has been suggested that many diseases such as Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, cirrhosis, diabetes, and cancer are associated with an abnormal concentration of endogenous H2S.104 Therefore, research on endogenous H2S, including the detection of H2S and utilizing H2S to develop specific nanotheranostic agents, has attracted considerable interest in the areas of medical, nanomaterial, and chemical science.

H2S-responsive smart nanoprobes

Given the key role of the H2S molecule in vivo, detection of this signaling molecule accurately is of great important.ance To date, many interests have been focused on the design of intelligent nanoprobes owing to their high sensitivity, high signal-to-noise ratio, real-time imaging, and simple operation features.105,106 Particularly, smart fluorescent probes with high sensitivity have attracted great attention. Generally, intelligent fluorescent probes were designed based on fluorescent molecules that can react with the H2S molecule, leading to the change of the fluorescent emission.107,108 Nevertheless, because of the low concentration of endogenous H2S and large amounts of interference molecules such as GSH and cysteine (Cys) in the complex biological systems, the design of H2S-responsive fluorescent probes with high sensitivity and chemical selectivity still remains a formidable challenge.

Zhao et al109 developed a boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY)-based fluorescence micelle as an H2S-responsive probe for detecting H2S. This probe micelle contained a semi-cyanine-BODIPY dye (BODInD-Cl) as the H2S interaction molecule, and BODIPY as a complementary energy donor of BODInD-Cl. The main feature of this nanoprobe is that the absorption of the energy acceptor BODInD-Cl will shift from 540 nm to 738 nm after the H2S trigger to reduce the efficiency of Förster resonance energy transfer, leading to the simultaneous “turn-on” of the fluorescent signal of energy donor BODIPY1 and “turn-off” of the fluorescent signal of energy acceptor BODInD-Cl. As a result, this probe can be used to quickly detect and track H2S using a fluorescence ratio. Besides, competition experiments showed that the red shift of the absorption peak of BODInD-Cl can only be mainly triggered by H2S, while the influence of other small molecules is very weak, demonstrating the high detecting selectivity of this probe. Zhang et al93 also designed a sulfoxide-functionalized BODIPY-based fluorescent probe for selectively detecting endogenous H2S by confining sulfoxide-functionalized BODIPY within the interior of porous silica matrix. The other influencing molecules with size larger than the aperture of the porous silica are unable to react with sulfoxide-functionalized BODIPY. Therefore, this common fluorescence molecule can only react with the small H2S molecule with a substantial red shift in absorption and emission, giving high chemical selectivity and sensitivity.

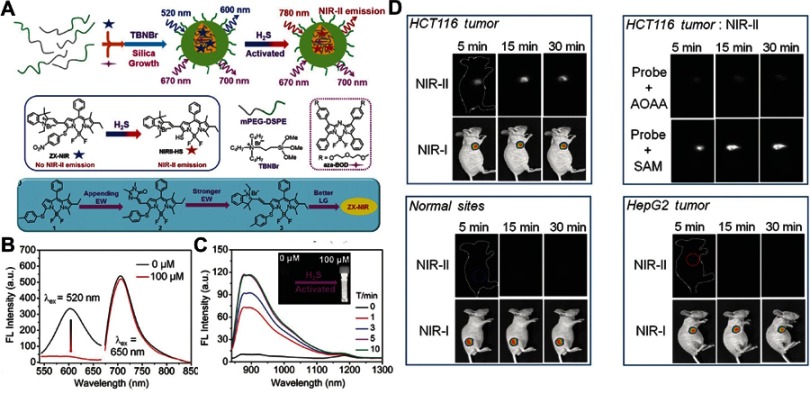

Given that NIR fluorescent probes have high resolution with deep-tissue penetration, Xu et al110 developed an H2S-activated NIR-II nanoprobe (NIR-II@Si) for visualizing colorectal cancers (Figure 10A). NIR-II@Si is composed of a covalently cross-linked silica shell with two organic chromophores in its cavity, in which a boron-dipyrromethene (ZX-NIR) dye serves as an H2S-responsive chromophore to generate NIR-II emission, and an H2S-inert aza-BODIPY (aza-BOD) dye with strong emission at 700 nm emission serves as internal reference. Upon reaction with H2S, ZX-NIR was transformed to NIRII-HS accompanied by maximum emission shifting from 600 to 900 nm, while aza-BOD keeps maximum emission at 700 nm with similar intensity, forming ratiometric fluorescence with high signal-to-background ratios (Figure 10B and C). This H2S-responsive ratiometric fluorescence nanoprobe with excellent targeting capability exhibits excellent performance for selectively identifying the H2S-rich colon cancer cells. Moreover, the merits of NIR-II imaging at depth and spatial resolution enable this H2S-responsive probe to accurately identify colorectal tumors in animal models (Figure 10D).

Figure 10.

(A) Schematic illustration of the design of the ratiometric NIR-II fluorescence nanoprobe (NIR-II@Si) and its H2S-responsive mechanism. (B) Fluorescence (FL) spectra of NIR-II@Si in PBS (pH 7.4) before and after addition of 100 μm NaHS. (C) Time-dependent fluorescence spectra of NIR-II@Si under the presence of 100 μm NaHS. (D) In vivo fluorescence imaging of different tumor-bearing mice using an H2S-activated NIR-II@Si nanoprobe. Figures A to D reprinted with permission from Xu G, Yan Q, Lv X, et al. Imaging of colorectal cancers using activatable nanoprobes with second near-infrared window emission. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2018;57(14):3626–3630.110 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: NIR, near-infrared; PEG, polythylene. glycol.

Because of the high spatial resolution and deep tissue imaging penetration of photoacoustic imaging, enormous interest has recently been devoted to designing a smart photoacoustic nanoprobe for H2S detection. Shi et al111 developed an H2S-activated photoacoustic imaging nanoprobe Si@BODPA for in vivo H2S detection. Si@BODPA was fabricated using biocompatible silica as a core shell to encapsulate semi-cyanine-BODPA into its interior.111 In the presence of H2S, a nucleophilic substitution reaction between H2S and BODPA caused BODPA to convert into BOD-HS, which displayed strong NIR absorption at 780 nm for photoacoustic imaging. Furthermore, Si@BODPA has excellent biocompatibility since the surface is modified by PEG. In the mode of HCT116 tumor-bearing mice, this Si@BODPA can provide real-time photoacoustic imaging of the endogenous H2S generated in the HCT116 tumor, demonstrating the high activating effect and great application potential of this smart nanoprobe.

H2S-responsive theranostic agents

H2S is also an overproduced molecule in some cancer cells, such as colon cancer.112 Currently, the maindiagnosis and therapy methods for colon cancer are colonoscopy diagnosis and surgical treatment, but there still remain some serious problems, such as missed diagnosis, misdiagnosis, recurrence, and metastasis.113 Using endogenous H2S to activate the diagnosis and therapy functions of smart theranostic agents has been considered an effectively strategy to reduce the rate of misdiagnosis and improve the treatment efficacy of colon cancer. To date, several nanomaterials, including a Cu-based metal–organic framework114 and CuO,115 have been explored for designing H2S-responsive theranostic agents.

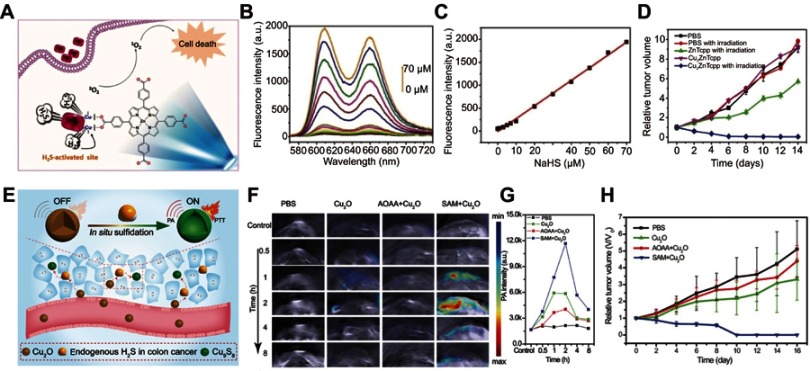

Ma et al prepared a colon cancer antitumor agent based on H2S-responsive photodynamic diagnosis (Figure 11A). They synthesized a copper-zinc mixed metal organic skeleton nanoparticle (NP-1), constructed of zinc metalated porphyrin (ZnTcpp) as ligand and Cu2+ ions as building blocks.116 In NP-1, ZnTcpp served as photosensitizer, while Cu2+ served as fluorescence quencher. Before activation, the fluorescence of ZnTcpp was quenched by Cu2+ ions, resulting in a low yield of singlet oxygen. Upon encountering H2S, the Cu2+ ions would react with H2S, followed by recovering the original fluorescence and singlet oxygen generation functions of NP-1 (Figure 11B and C). Cell and mouse tumor model treatment experiments demonstrated that NP-1 has excellent photodynamic efficiency upon triggering by endogenous H2S (Figure 11D).

Figure 11.

(A) Simple structure of copper–zinc mixed metal–organic framework NP-1 and proposed H2S-activated 1O2 generation for cancer therapy. (B) Fluorescence spectra of NP-1 after reaction with different concentrations of NaHS. (C) The linear releationship between the fluorescence intensity of NP-1 and the added concentration of NaHS. (D) Relative tumor volume change after different treatments. Figures A to D reprinted with permission from Ma Y, Li X, Li A, et al. H2S-activable MOF nanoparticle photosensitizer for effective photodynamic therapy against cancer with controllable singlet-oxygen release. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2017;56(44):13752–13756.116 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. (E) Schematic illustration of in situ reaction between endogenous H2S and Cu2O for activating photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy (PTT). (F) In vivo photoacoustic imaging and (G) corresponding signal intensity of tumor-bearing mice for different groups. (H) Time-varying relative tumor volume after different treatments. Figures E to H reprinted with permission from An L, Wang X, Rui X, et al. The in situ sulfidation of Cu2O by endogenous H2S for colon cancer theranostics. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2018;57(48):15782–15786.117 Copyright © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Abbreviations: NP, nanoparticle; ZnTcpp, zinc metalated porphyrin.

An et al117 designed a simultaneous turn-on photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy agent based on in situ reaction of cuprous oxide (Cu2O) with endogenous H2S at colon tumor sites (Figure 11E). The original agent of Cu2O exhibited no obvious absorption in the NIR region before reaction with H2S, giving a weak photoacoustic signal and photothermal effect at the normal tissue (Figure 11F and G). When Cu2O entered the tumor site, the endogenous H2S would trigger sulfidation of Cu2O to form copper sulfide (Cu9S8), accompanied by strong absorption in the NIR region. This activated NIR absorption can be used for photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy of colon cancer tumor with high diagnosis sensitivity and minimal damage (Figure 11H).

Summary and outlook

In summary, this article presents recent advances in the design and fabrication of pH, GSH, H2O2, and H2S-responsive nanomedicine agents, and their application in tumor diagnosis and treatment. Because the diagnosis and treatment functions of smart nanomedicine were designed to be silenced before activation, while turned “on” upon triggering by the TME, they exhibited higher theranostic sensitive and selectivity with lower harmful side effects, as compared with traditional nanomedicine agents. These merits make them highly promising for improving tumor diagnosis and therapy. In fact, in addition to pH, H2O2, GSH, and H2S, there are many other TME-stimulating elements (eg, hypoxia, immune, enzyme, and protein) and exogenous elements (eg, light, magnetism, and ultrasound) that can be utilized to design smart nanomedicine agents.45 Furthermore, these elements can be merged together to explore multiresponsive nanomedicine agents.23 In this case, it is possible to activate the synergistic theranostic functions (eg, control the release of different drugs) at expected time points, further improving the tumor theranostic efficacies and mitigating the side effects. Besides, the permeable barriers for nanodrugs to effectively enter the tumor cells are also possible to overcome through multiresponsive steps. Despite these promising results, there are still many challenges to overcome for TME-responsive nanomedicine agents toward the clinical translation. Firstly, the safety issues of nanomedicine agents need to be thoroughly investigated. Secondly, the triggering efficiency of nanomedicine agents needs to be improved since the concentration of overproduced substances and the accumulation of nanoparticles in the tumor site are very limited. Finally, but not the least, the activated selectivity of nanomedicine agents needs to be further improved because most of the tumor-overexpressed substances also exist in the normal organs/tissues. Nevertheless, it is believed that with the continuous development of science and technology, these problems will be overcome, and these TME-responsive nanomedicine agents will facilitate the improvement of tumor diagnosis and therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21601124, 21671135, and 21701111), Shanghai Sailing Program (17YF1413700), Ministry of Education of China (PCSIRT_IRT_16R49), and International Joint Laboratory on Resource Chemistry.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in regard to this work.

References

- 1.Wang L, Huo M, Chen Y, et al. Tumor microenvironment-enabled nanotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7(8):1701156. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201701156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt AP, Redinbo MR, Bultman SJ. The role of the microbiome in cancer development and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):326–344. doi: 10.3322/caac.21398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin SY, Zhang AQ, Cheng SX, et al. Drug self-delivery systems for cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2017;112:234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong H, Dong Z, Liu Y, et al. Engineering of multifunctional nano-micelles for combined photothermal and photodynamic therapy under the guidance of multimodal imaging. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24(41):6492–6502. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201401451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim C, Favazza C, Wang LV. In vivo photoacoustic tomography of chemicals: high-resolution functional and molecular optical imaging at new depths. Chem Rev. 2010;110(5):2756–2782. doi: 10.1021/cr900266s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Zerda A, Kim J-W, Galanzha EI, et al. Advanced contrast nanoagents for photoacoustic molecular imaging, cytometry, blood test and photothermal theranostics. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6(5):346–369. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maji SK, Sreejith S, Joseph J, et al. Upconversion nanoparticles as a contrast agent for photoacoustic imaging in live mice. Adv Mater. 2014;26(32):5633–5638. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian C, Feng P, Yu J, et al. Anaerobe-inspired anticancer nanovesicles. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2017;56(10):2588–2593. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C, Bu W, Ni D, et al. Synthesis of iron nanometallic glasses and their application in cancer therapy by a localized Fenton reaction. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2016;55(6):2101–2106. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu W, Gao Y, Jiao Y, et al. Carbon nano-dots as a fluorescent and colorimetric dual-readout probe for the detection of arginine and Cu2+ and its logic gate operation. Nanoscale. 2017;9(32):11545–11552. doi: 10.1039/c7nr02336g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Mendoza-Garcia A, Li Q, et al. Organic phase syntheses of magnetic nanoparticles and their applications. Chem Rev. 2016;116(18):10473–10512. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian Q, Tang M, Sun Y, et al. Hydrophilic flower-like CuS superstructures as an efficient 980 nm laser-driven photothermal agent for ablation of cancer cells. Adv Mater. 2011;23(31):3542–3547. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Shi J. Hollow-structured mesoporous materials: chemical synthesis, functionalization and applications. Adv Mater. 2014;26(20):3176–3205. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Li C, Liu Y, et al. Gold nanoclusters-based nanoprobes for simultaneous fluorescence imaging and targeted photodynamic therapy with superior penetration and retention behavior in tumors. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(8):1314–1325. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201403095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Shi J. Chemistry of mesoporous organosilica in nanotechnology: molecularly organic–inorganic hybridization into frameworks. Adv Mater. 2016;28(17):3235–3272. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun C-Y, Qin C, Wang C-G, et al. Chiral nanoporous metal-organic frameworks with high porosity as materials for drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2011;23(47):5629–5632. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Y, Xu C, Sun X, et al. Nanoparticle design strategies for enhanced anticancer therapy by exploiting the tumour microenvironment. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(12):3830–3852. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00592f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm S, Tavares AJ, Dai Q, et al. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:16014. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torchilin V. Tumor delivery of macromolecular drugs based on the EPR effect. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(3):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogbomo SM, Shi W, Wagh NK, et al. 177Lu-labeled HPMA copolymers utilizing cathepsin B and S cleavable linkers: synthesis, characterization and preliminary in vivo investigation in a pancreatic cancer model. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40(5):606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang C, Soenen SJ, Rejman J, et al. Magnetic electrospun fibers for cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22(12):2479–2486. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201102171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv D, Wang R, Tang G, et al. Ecofriendly electrospun membranes loaded with visible-light-responding nanoparticles for multifunctional usages: highly efficient air filtration, dye scavenging, and bactericidal activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(13):12880–12889. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b01508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma B, Wang S, Liu F, et al. Self-assembled copper–amino acid nanoparticles for in situ glutathione “and” H2O2 sequentially triggered chemodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(2):849–857. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y, Aimetti AA, Langer R, et al. Bioresponsive materials. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;2:16075. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Wu W, Li R-Q, et al. Peptide-based multifunctional nanomaterials for tumor imaging and therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(50):1804492. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201804492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reina-Campos M, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco M. Metabolism shapes the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;48:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Liu X, Yuan H, et al. Therapeutic remodeling of the tumor microenvironment enhances nanoparticle delivery. Adv Sci. 2019;6(5):1802070. doi: 10.1002/advs.201802070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R, Yan F, Chen Y. Exogenous physical irradiation on titania semiconductors: materials chemistry and tumor-specific nanomedicine. Adv Sci. 2018;5(12):1801175. doi: 10.1002/advs.v5.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ju E, Dong K, Liu Z, et al. Tumor microenvironment activated photothermal strategy for precisely controlled ablation of solid tumors upon NIR irradiation. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(10):1574–1580. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201403885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang K, Zhu L, Nie L, et al. Visualization of protease activity in vivo using an activatable photo-acoustic imaging probe based on CuS nanoparticles. Theranostics. 2014;4(2):134–141. doi: 10.7150/thno.7217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma T, Zhang P, Hou Y, et al. “Smart” nanoprobes for visualization of tumor microenvironments. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7(20):1800391. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201800391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swietach P, Vaughan-Jones RD, Harris AL. Regulation of tumor pH and the role of carbonic anhydrase 9. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(2):299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9064-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thews O, Gassner B, Kelleher DK, et al. Impact of extracellular acidity on the activity of P-glycoprotein and the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs. Neoplasia. 2006;8(2):143–152. doi: 10.1593/neo.05697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du JZ, Du X-J, Mao CQ, et al. Tailor-made dual pH-sensitive polymer–doxorubicin nanoparticles for efficient anticancer drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(44):17560–17563. doi: 10.1021/ja207150n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Zhou K, Huang G, et al. A nanoparticle-based strategy for the imaging of a broad range of tumours by nonlinear amplification of microenvironment signals. Nat Mater. 2013;13:204. doi: 10.1038/nmat3819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longo DL, Sun PZ, Consolino L, et al. A general MRI-CEST ratiometric approach for pH imaging: demonstration of in vivo pH mapping with iobitridol. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(41):14333–14336. doi: 10.1021/ja5059313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wencel D, Kaworek A, Abel T, et al. Optical sensor for real-time pH monitoring in human tissue. Small. 2018;14(51):1803627. doi: 10.1002/smll.201803627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi W, Li X, Ma H. A tunable ratiometric pH sensor based on carbon nanodots for the quantitative measurement of the intracellular pH of whole cells. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2012;51(26):6432–6435. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Ni D, Liu Y, et al. Magnesium silicide nanoparticles as a deoxygenation agent for cancer starvation therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:378. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu J, Sun J, Li F, et al. Highly sensitive diagnosis of small hepatocellular carcinoma using pH-responsive iron oxide nanocluster assemblies. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(32):10071–10074. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Qu Z, Cao H, et al. pH switchable nanoassembly for imaging a broad range of malignant tumors. ACS Nano. 2017;11(12):12446–12452. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b06483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin J, Xin P, An L, et al. Fe3O4–ZIF-8 assemblies as pH and glutathione responsive T2–T1 switching magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent for sensitive tumor imaging in vivo. Chem Commun. 2019;55(4):478–481. doi: 10.1039/C8CC08943D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Q, Liu X, Chen J, et al. A self-assembled albumin-based nanoprobe for in vivo ratiometric photoacoustic pH imaging. Adv Mater. 2015;27(43):6820–6827. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin T, Wang L, Yin L, et al. Co-delivery of hydrophobic paclitaxel and hydrophilic AURKA specific siRNA by redox-sensitive micelles for effective treatment of breast cancer. Biomaterials. 2015;61:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mo R, Gu Z. Tumor microenvironment and intracellular signal-activated nanomaterials for anticancer drug delivery. Mater Today. 2016;19(5):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.11.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye G, Jiang Y, Yang X, et al. Smart nanoparticles undergo phase transition for enhanced cellular uptake and subsequent intracellular drug release in a tumor microenvironment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(1):278–289. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b15978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng H, Zhang Y, Liu L, et al. One-pot synthesis of metal–organic frameworks with encapsulated target molecules and their applications for controlled drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(3):962–968. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H, Li Q, Liu R, et al. A versatile prodrug strategy to in situ encapsulate drugs in MOF nanocarriers: a case of cytarabine-IR820 prodrug encapsulated ZIF-8 toward chemo-photothermal therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(35):1802830. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201802830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang C, Soenen SJ, Rejman J, et al. Stimuli-responsive electrospun fibers and their applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(5):2417–2434. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00181c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao S, Tang G, Hua D, et al. Stimuli-responsive bio-based polymeric systems and their applications. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(5):709–729. doi: 10.1039/C8TB02491J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hua D, Liu Z, Wang F, et al. pH responsive polyurethane (core) and cellulose acetate phthalate (shell) electrospun fibers for intravaginal drug delivery. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;151:1240–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong W, Zhou H, Zhang C, et al. An amino acid-based gelator for injectable and multi-responsive hydrogel. Chin Chem Lett. 2017;28(11):2125–2128. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2017.09.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reshetnyak YK, Andreev OA, Lehnert U, et al. Translocation of molecules into cells by pH-dependent insertion of a transmembrane helix. Pans. 2006;103(17):6460–6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601463103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ling D, Park W, Park SJ, et al. Multifunctional tumor pH-sensitive self-assembled nanoparticles for bimodal imaging and treatment of resistant heterogeneous tumors. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(15):5647–5655. doi: 10.1021/ja4108287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang Z, Fan W, Tang W, et al. Near-infrared semiconducting polymer brush and pH/GSH-responsive polyoxometalate cluster hybrid platform for enhanced tumor-specific phototheranostics. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2018;57(43):14101–14105. doi: 10.1002/anie.201808074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Choi J, Bang D, et al. Convertible organic nanoparticles for near-infrared photothermal ablation of cancer cells. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2011;50(2):441–444. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng F, Hennink WE, Zhong Z. Reduction-sensitive polymers and bioconjugates for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2009;30(12):2180–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao W, Hu J, Gao W. Glucose oxidase–polymer nanogels for synergistic cancer-starving and oxidation therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(28):23528–23535. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b06814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Cai X, Yu A, et al. Redox-sensitive self-assembled nanoparticles based on alpha-tocopherol succinate-modified heparin for intracellular delivery of paclitaxel. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;496:311–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Liu H, Shu X, et al. A reduction-degradable polymer prodrug for cisplatin delivery: preparation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Colloid Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015;136:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duda F, Kieke M, Waltz F, et al. Highly biocompatible behaviour and slow degradation of a LDH (layered double hydroxide)-coating on implants in the middle ear of rabbits. J Mater Sci-Mater Med. 2015;26(1):9. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5334-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baldwin AD, Kiick KL. Reversible maleimide–thiol adducts yield glutathione-sensitive poly(ethylene glycol)–heparin hydrogels. Polym Chem. 2013;4(1):133–143. doi: 10.1039/C2PY20576A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan Z, Gui L, Zheng J, et al. GSH-activated light-up near-infrared fluorescent probe with high affinity to αvβ3 integrin for precise early tumor identification. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(37):30994–31007. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b09841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan D, Ding L, Sun Z, et al. MRI/Fluorescence bimodal amplification system for cellular GSH detection and tumor cell imaging based on manganese dioxide nanosheet. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1747. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20110-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gaspar VM, Baril P, Costa EC, et al. Bioreducible poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)–PLA–PEI-SS triblock copolymer micelles for co-delivery of DNA minicircles and doxorubicin. J Control Release. 2015;213:175–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo Z, Cai K, Hu Y, et al. Redox-responsive molecular nanoreservoirs for controlled intracellular anticancer drug delivery based on magnetic nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2012;24(3):431–435. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shao N, Jin J, Wang H, et al. Design of bis-spiropyran ligands as dipolar molecule receptors and application to in vivo glutathione fluorescent probes. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(2):725–736. doi: 10.1021/ja908215t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang J, Sun X, Mao W, et al. Tumor redox heterogeneity-responsive prodrug nanocapsules for cancer chemotherapy. Adv Mater. 2013;25(27):3670–3676. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu L, Chen Y, Wu M, et al. “Manganese extraction” strategy enables tumor-sensitive biodegradability and theranostics of nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(31):9881–9894. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Townsend DM, Tew KD, Tapiero H. The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57(3):145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matsui H, Oaki Y, Imai H. Tunable photochemical properties of a covalently anchored and spatially confined organic polymer in a layered compound. Nanoscale. 2016;8(21):11076–11083. doi: 10.1039/c6nr02368a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deng R, Xie X, Vendrell M, et al. Intracellular glutathione detection using MnO2-nanosheet-modified upconversion nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(50):20168–20171. doi: 10.1021/ja2100774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cai W, Wang J, Liu H, et al. Gold nanorods@metal-organic framework core-shell nanostructure as contrast agent for photoacoustic imaging and its biocompatibility. J Alloy Compd. 2018;748:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.03.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee H, Shin T-H, Cheon J, et al. Recent developments in magnetic diagnostic systems. Chem Rev. 2015;115(19):10690–10724. doi: 10.1021/cr500698d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gong F, Cheng L, Yang N, et al. Bimetallic oxide MnMoOX nanorods for in vivo photoacoustic imaging of GSH and tumor-specific photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 2018;18(9):6037–6044. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu Y, Yang Z, Huang X, et al. Glutathione-responsive self-assembled magnetic gold nanowreath for enhanced tumor imaging and imaging-guided photothermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12(8):8129–8137. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li J, Ke W, Wang L, et al. Self-sufficing H2O2-responsive nanocarriers through tumor-specific H2O2 production for synergistic oxidation-chemotherapy. J Control Release. 2016;225:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Y, Zhen W, Jin L, et al. All-in-one theranostic nanoagent with enhanced reactive oxygen species generation and modulating tumor microenvironment ability for effective tumor eradication. ACS Nano. 2018;12(5):4886–4893. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]