Abstract

13C-hyperpolarized carboxylates, such as pyruvate and acetate, are emerging molecular contrast agents for MRI visualization of various diseases, including cancer. Here we present a systematic study of 1H and 13C parahydrogen-induced polarization of acetate and pyruvate esters with ethyl, propyl and allyl alcoholic moieties. It was found that allyl pyruvate is the most efficiently hyperpolarized compound from those under study, yielding 21% and 5.4% polarization of 1H and 13C nuclei, respectively, in CD3OD solutions. Allyl pyruvate and ethyl acetate were also hyperpolarized in aqueous phase using homogeneous hydrogenation with parahydrogen over water-soluble rhodium catalyst. 13C polarization of 0.82% and 2.1% was obtained for allyl pyruvate and ethyl acetate, respectively. 13C-hyperpolarized methanolic and aqueous solutions of allyl pyruvate and ethyl acetate were employed for in vitro MRI visualization, demonstrating the prospects for translation of the presented approach to biomedical in vivo studies.

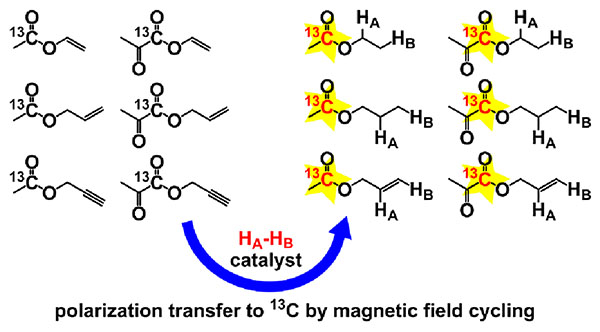

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

Hyperpolarization of nuclear spins allows to enhance NMR signal by several orders of magnitude at magnetic fields of a few tesla.1–4 The obtained hyperpolarized (HP) molecules can be used as contrast agents for metabolic studies and molecular imaging.5,6 Currently, in this context the most important HP compound is pyruvate which is metabolized to lactate in vivo.7 In tumor tissues, the rates of aerobic glycolysis and reduction of pyruvate to lactate are usually significantly higher compared to normal tissue (the so-called Warburg effect8). Thus, HP Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI) quantification of lactate-to-pyruvate ratio can be used for cancer diagnosis using the intravenous injection of HP pyruvate, which significantly improves the sensitivity of this approach, allowing tumor diagnosis6,9,10 as well as monitoring of tumor grading11 and the response to cancer treatment.12,13 The use of HP pyruvate has been already approved for the imaging of prostate cancer in clinical trials.14,15 Another HP compound, which attracts significant research (and future clinical) interest is acetate which can be utilized for studying metabolism in the brain,16,17 liver,18 kidney19 and muscle.20 It should be mentioned that for biomedical applications hyperpolarization of 13C nuclei in these compounds is strongly preferable, due to significantly longer relaxation times and negligible in vivo background signal compared to those of protons.21

Currently, dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization (d-DNP) technique is the most developed one for the production of HP molecules in solution for biomedical applications.22–24 However, the high cost and complexity of d-DNP equipment limit its widespread use in research and in future clinical use. A promising alternative is the use of significantly more affordable parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP) technique.25–29 PHIP is based on the pairwise addition of a parahydrogen (p-H2) molecule to an unsaturated substrate. Here pairwise addition means that the molecule of a reaction product contains two H atoms that came from the same p-H2 molecule. Pairwise addition of p-H2 allows to convert singlet spin order of parahydrogen into enhanced Zeeman magnetization of 1H nuclei of the hydrogenation product.30 The resultant hyperpolarization can be transferred to heteronuclei, including 13C, either spontaneously31,32 or by the use of magnetic field cycling (MFC)33,34 or radiofrequency (RF) pulse sequences.35–39 The possibility of the utilization of 13C-PHIP-hyperpolarized compounds as in vivo contrast agents for MRI was recently demonstrated in the laboratory animals.40–46 However, there are two major limitations that currently prevent PHIP from implementation in clinic. First of all, pairwise p-H2 addition requires the use of a hydrogenation catalyst. Usually, PHIP experiments are performed with homogeneous catalysts which represent transition metal complexes dissolved in organic solvent.47 The toxicity of these catalysts demands their separation from the obtained HP compound before the injection into a patient. A possible solution of this problem is the use of heterogeneous catalysts48 which can be easily filtered out49,50 or employed in continuous flow hydrogenation of unsaturated substrate vapors with subsequent dissolution of HP reaction product,51 though improving of polarization levels provided by these catalysts is highly desirable. Another approach is to perform hydrogenation of an unsaturated precursor with p-H2 over a homogeneous catalyst in an organic solvent, and then to chemically transform the resulting HP reaction product into a water-soluble form, which can be separated into an aqueous phase by extraction.52 The second limitation of PHIP is the availability of an unsaturated precursor which could be hydrogenated into the product of interest. This requirement makes it challenging to hyperpolarize such molecules as pyruvate or acetate by PHIP directly. PHIP side-arm hydrogenation (PHIP-SAH) approach,53–55 recently introduced by Reineri and co-workers, allows one to overcome this problem and to produce 13C HP carboxylates by PHIP. The idea of PHIP-SAH is based on hydrogenation of a 13C containing unsaturated ester (e.g., 1-13C-propargyl pyruvate) with p-H2 with subsequent polarization transfer from protons to 13C carboxyl nucleus followed by hydrolysis of the hydrogenated ester to form 13C HP carboxylate. The combination of PHIP-SAH with aqueous phase extraction after hydrolysis allows one to obtain pure aqueous solution of 13C HP pyruvate which has been already demonstrated useful for metabolic studies.56,57 When polarization transfer was performed with the use of magnetic field cycling, 13C polarization up to ~5% for 1-13C-pyruvate in aqueous phase was demonstrated.55 Korchak et al. showed that up to ~19% 13C polarization can be obtained for 1-13C-acetate-d3 with the use of fully deuterated vinyl acetate precursor as a substrate and ESOTHERIC RF pulse sequence for polarization transfer.58 Importantly, in order to obtain the maximum 13C polarization in PHIP-SAH experiments one needs to optimize all parameters, including the choice of unsaturated moiety, hydrogenation reaction conditions and polarization transfer procedure. Though several different unsaturated esters were employed in PHIP-SAH studies before,53,54,59 the effect of unsaturated moiety nature on the obtained polarization was not reported. In this work, we present a systematic study of 1H and 13C PHIP-SAH hyperpolarization of acetate and pyruvate esters with ethyl, propyl and allyl moieties. These esters were obtained by homogeneous hydrogenation of corresponding unsaturated precursors (vinyl, allyl and propargyl esters, respectively) with p-H2 in organic and aqueous phases.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

Commercially available bis(norbornadiene)rhodium(I) tetrafluoroborate ([Rh(NBD)2]BF4, NBD = norbornadiene, Strem 45–0230), 1,4-bis(diphenylphosphino)butane (dppb, Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), (norbornadiene)[1,4-bis(diphenylphosphino)butane]rhodium(I) tetrafluoroborate ([Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4, Sigma-Aldrich) and ultrapure hydrogen (>99.999%) were used as received. Unsaturated precursors (vinyl acetate, allyl acetate, propargyl acetate, vinyl pyruvate, allyl pyruvate and propargyl pyruvate, see Chart 1) were synthesized according to procedures reported elsewhere.60 In this study, we used propargyl and allyl esters with both natural abundance of 13C nuclei (1.1%) and ~98% 13C enrichment in the carboxyl group. Vinyl acetate was used with ~98% 13C enrichment only, because detailed homogeneous PHIP-SAH investigation of this substrate was reported previously.61 In contrast, vinyl pyruvate was used only with ~1.1% 13C content because the 13C labeled precursor was not available to us (see previous paper60 for details).

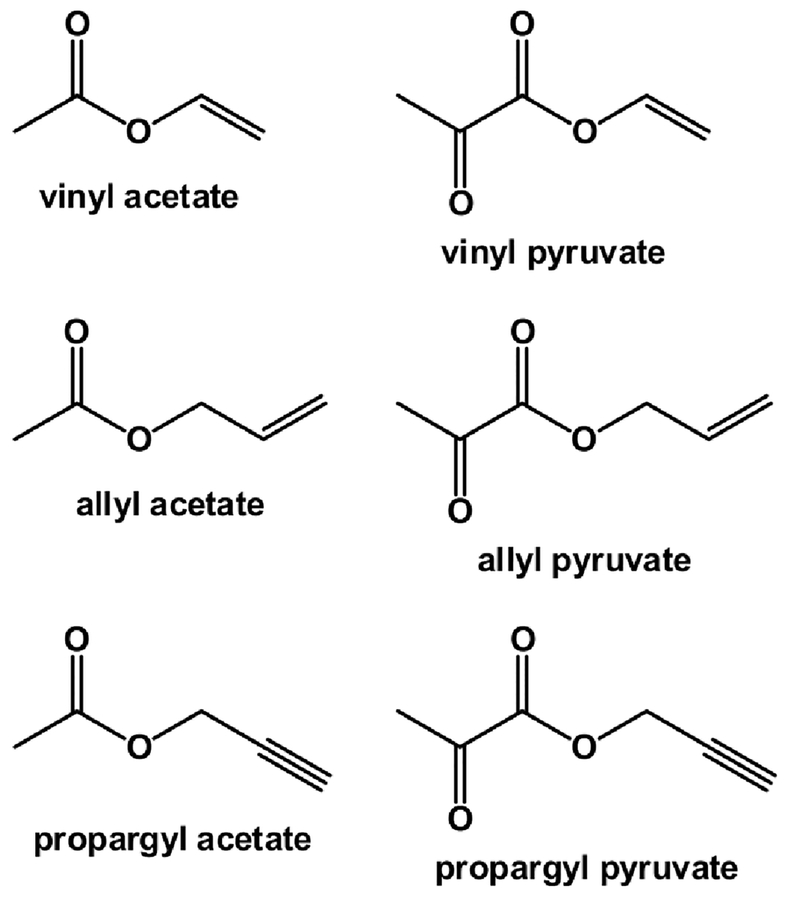

Chart 1.

Structures of unsaturated precursors used for PHIP-SAH experiments in this study. Structures of all compounds employed in this study (including unsaturated precursors, reaction products, ligands, products of ligand hydrogenation, etc.) are presented in Chart S1.

PHIP experiments.

In most of the experiments H2 gas was enriched with parahydrogen using custom-built p-H2 generator based on cryocooler module (SunPower, P/N 100490, CryoTel GT; a more detailed description of the generator was published elsewhere60). For the work presented here, the generator was operated at 43−66 K, resulting in approximately 85−60% p-H2 enrichment. The 1H NMR data for hyperpolarization of ethyl acetate was obtained with 88.5% parahydrogen produced using Bruker Parahydrogen Generator BPHG 90. The samples for homogeneous PHIP experiments were prepared as follows. For hydrogenation in CD3OD, [Rh(NBD)2]BF4, dppb and unsaturated precursor (in 1:1:16 molar ratio) were dissolved in a required amount of CD3OD and mixed using a vortex mixer to obtain a solution with 5 mM concentration of the catalyst and the ligand and 80 mM concentration of the substrate. The obtained solutions were placed in the standard 5 mm Wilmad NMR tubes tightly connected with 1/4 in. outer diameter PTFE tubes (the sample volume was 0.7 mL). The exception was the case of 13C MRI experiments where medium-wall 5 mm NMR tubes were used (Wilmad glass P/N 503-PS-9; the sample volume was 0.5 mL). For hydrogenation in D2O, a previously described procedure was employed for the preparation of aqueous catalyst solution (~5.3 mM or 10 mM concentration) in D2O.62 In brief, the solution of disodium salt of 1,4-bis[(phenyl-3-propanesulfonate)phosphine]butane in H2O was degassed with a rotary evaporator. Then solution of [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 in acetone was added dropwise with subsequent degassing. Next, the required amount of unsaturated precursor was added resulting in ~80 mM concentration. The obtained solutions were placed in medium-wall 5 mm NMR tubes (Wilmad glass P/N 503-PS-9; the sample volume was 0.5 mL), tightly connected with 1/4 in. outer diameter PTFE tubes. All glassware was flushed with argon right before the addition of any solution inside.

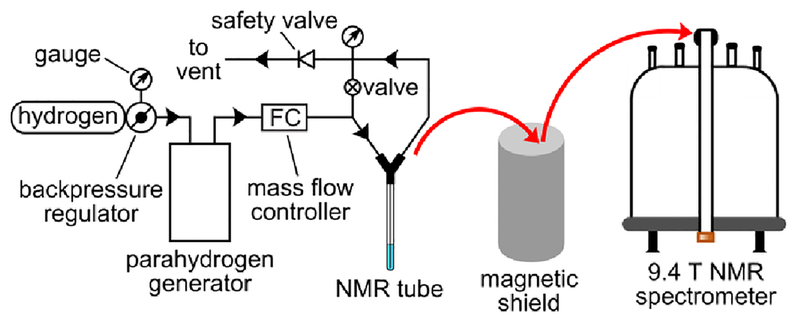

The overall scheme of experimental setup is presented in Figure 1. In case of PHIP experiments with methanolic solutions, the samples were pressurized up to 40 psig and preheated up to 40 °C using NMR spectrometer temperature control unit (except the 1H NMR data for hyperpolarization of ethyl acetate that was obtained at 35 psig pressure). Hydrogen gas flow rate (40 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm)) was regulated with a mass flow controller (SmartTrak 50, Sierra Instruments, Monterey, CA). After termination of p-H2 bubbling, the samples were placed either directly inside the probe of the NMR spectrometer (in case of ALTADENA63 experiments) or inside the MuMETAL magnetic shield described in detail elsewhere61 (in case of MFC experiments). The magnetic field inside the shield was adjusted using additional solenoid placed inside the previously degaussed three-layered MuMETAL shield (Magnetic Shield Corp., Bensenville, IL, P/N ZG-206). This previously calibrated solenoid was powered by a direct current (DC) power supply (GW-Instek, GPR-30600), and the DC current was attenuated by a resistor bank (Global Specialties, RDB-10) to achieve the desired magnetic field inside the MuMETAL shield. The mu-metal shield provides an isolation of approximately 1,200 according to the manufacturer’s specification; therefore, the use of the shield in the Earth’s magnetic field results in the minimum residual magnetic field of approximately 40 nT. After placing inside the magnetic shield the samples were slowly (~1 s) pulled out of the shield and quickly placed inside the probe of the NMR spectrometer. The total sample transfer time was ~8 s after the termination of H2 gas bubbling. Experiments with aqueous solutions were carried out using the same experimental procedure except that higher pressure (70 or 80 psig), temperature (55–95 °C) and hydrogen gas flow rate (140 sccm) were used. Heating to temperatures higher than 60 °C was performed using a beaker with hot water. Also in case of aqueous solutions PASADENA25 experiments were performed in addition to ALTADENA and MFC experiments. In this case, the samples were residing inside the NMR spectrometer probe during all operations. In MFC experiments with MRI detection also higher pressure (70 psig), temperature (80–95 °C) and hydrogen gas flow rate (140 sccm) were used. After pulling the samples out of the shield they were depressurized, the NMR tube was disconnected from the setup, and the solution was injected into an imaging phantom (~2.8 mL hollow spherical plastic ball) located inside the RF coil of an MRI scanner using a syringe. The sample transfer time to an MRI scanner was ~20 s.

Figure 1.

The diagram of experimental setup for 13C hyperpolarization and NMR spectroscopic detection of acetate and pyruvate esters. Adopted with permission from references60,64. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

NMR spectra were acquired on a 9.4 T Bruker NMR spectrometer (except the 1H NMR data for hyperpolarization of ethyl acetate that was obtained on a 7.05 T Bruker AV 300 NMR spectrometer) using a 90° RF pulse, except PASADENA25 experiments which were performed using a 45° RF pulse. The 1H ALTADENA and 13C PHIP spectra were acquired as pseudo-two-dimensional (2D) sets consisting of 64 1D NMR spectra (acquisition time 1 s) to avoid delays between placing the sample into the probe and starting the acquisition. The acquisition always started before placing the sample inside the NMR probe. MR images were obtained on a 15.2 T small-animal Bruker MRI scanner using 15 mm outer diameter round surface RF coil and true steady state precession (true-FISP) RF pulse sequence. The excitation pulse angle was optimized on a thermally polarized phantom containing 2.8 mL of 3 M solution of sodium 1-13C-acetate in D2O. For 3D imaging experiments, the isotropic field of view (FOV) was 48 mm and imaging matrix of 64×64×8 resulting in 0.75×0.75×6 mm3 spatial resolution. The repetition time (TR) was ~5 ms, and echo time (TE) was ~2.5 ms. The total acquisition time was ~2.5 s. For 2D MRI experiments, FOV of 48×48 mm2 was used with the slab thickness of 48 mm resulting in effectively no slice selection with respect to the phantom depth. The TR and TE parameters were the same.

Calculation of NMR Signal Enhancement and Nuclear Spin Polarization

1H NMR signal enhancement factors (ε1H) were calculated using NMR signals of thermally polarized reaction product molecules as a reference, according to the following equation:

where I1H-PHIP is the intensity of PHIP signal of a particular group of protons, I1H-thermal is the averaged signal per proton in a thermally polarized molecule. The I1H-thermal values were calculated as follows:

where M is the number of different groups of protons in a molecule, Ii is the intensity of the NMR signal for the group of protons with index i, Ni is the number of protons in this group. The overlapping NMR signals (for example, signals of CH3 groups of carboxyl moieties) were omitted from these calculations. It should be noted that, in principle, hydrogenation reaction may continue during the delay between acquisition of PHIP and thermal NMR spectra, leading to underestimation of NMR signal enhancements. It was found that in our conditions this effect does not have a significant impact on the obtained ε values. Figure S1 in the Supporting Information presents two thermal 1H NMR spectra acquired after bubbling of p-H2 for 4 s through the solution of propargyl pyruvate and [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst in CD3OD with a 30-min delay between them. These two spectra were found to be almost identical despite the facts that (i) conversion of propargyl pyruvate was only ~16%, i.e. there is significant amount of reactant left; (ii) there is a significant amount of dissolved hydrogen manifested in the NMR signal of ortho-H2 at 4.52 ppm; (iii) propargyl pyruvate is the most reactive substrate from those under study, see Results and Discussion section. Therefore, it is concluded that hydrogenation reaction proceeds to significant extent only under conditions of hydrogen bubbling when the solution is intensely agitated.

In experiments with substrates containing 13C nuclei at natural abundance, 13С NMR signal enhancement factors (ε13С) were calculated using the NMR signal of 740 mM solution of 1-13C-vinyl acetate (with 98% 13C enrichment) in CD3OD as an external reference, according to the following equation:

where I13C-PHIP is the intensity of 13C PHIP NMR signal, I13C-ref is the intensity of 13C NMR signal of the reference sample, Cref = 740 mM is the concentration of vinyl acetate in the reference sample, Creactant = 80 mM is the initial concentration of the reactant before hydrogenation, X (%) is the chemical conversion of the reactant estimated using 1H NMR spectra acquired after relaxation of polarization, φref = 0.98 is 13C enrichment of vinyl acetate in the reference sample, φreactant = 0.011 is the 13C enrichment of the substrate. The use of external reference was necessary because it was not possible to acquire thermal 13C NMR signals for the hydrogenated samples in reasonable time.

In experiments with 13C-enriched substrates, 13С NMR signal enhancement factors (ε13С) were calculated using 13C NMR signals of thermally polarized reaction product molecules as a reference:

where I13C-PHIP is the intensity of 13C PHIP NMR signal, I13C-thermal is the intensity of 13C NMR signal of thermally polarized sample, RGthermal = 203 or 1 is the receiver gain used for acquisition of thermal signal, RGPHIP = 1 is the receiver gain used for acquisition of PHIP signal, NSthermal = 1, 2, 4 or 8 and NSPHIP = 1 are the number of signal accumulations used for the acquisition of thermal and PHIP NMR spectra, respectively. The use of different receiver gain values was necessary because it usually was not possible to obtain thermal 13C NMR signals for the hydrogenated samples with RG = 1 in reasonable time. On the other hand, acquisition of PHIP spectra with RG = 203 led to signal overflow. According to vendor specifications, there is a linear dependence between the observed NMR signal and RG. The deviation of RG function from linearity is expected to be less than 10%,65 which we consider satisfactory for our purposes. In most of the experiments, thermal 13C NMR spectra were acquired with several signal accumulations in order to obtain signal which can be integrated with sufficient accuracy.

Nuclear spin polarizations P1H and P13C were calculated using the formula

where P0 is the equilibrium nuclear spin polarization of 1H or 13C at the 9.4 T magnetic field (at 313 K, P0 = 3.1×10–3% for 1H and P0 = 7.7×10–4% for 13C). Because experiments were performed with broadly varied p-H2 fraction (60–85%), the observed polarizations were also recalculated to the highest utilized p-H2 fraction (85%) for the sake of comparison using the following equation:29

where P85% is the polarization recalculated to 85% p-H2 fraction and χp is the p-H2 fraction employed in a particular experiment. Polarization transfer efficiency η was calculated as a ratio of the maximum obtained P13C and P1H values for each HP compound:

Since the samples were manually transferred from the low to the high magnetic field and the duration of p-H2 bubbling was also manually controlled, the reproducibility test was carried out. For this, hyperpolarization of ethyl acetate was followed using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Ten repetitions of p-H2 addition to vinyl acetate have been performed and yielded relative standard errors of 6% or less for the vinyl acetate conversion, 1H ALTADENA signal intensities, signal enhancements and 1H polarization (see Table S1). Therefore, we expect the numerical data presented in this work to have standard errors on the order of ~6% due to shot-to-shot reproducibility in most cases.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General considerations.

The PHIP experiments were generally performed according to the following scenario. First, 1H ALTADENA experiments with various duration of p-H2 bubbling were carried out. Then the duration of p-H2 bubbling, which was optimal in terms of the resultant 1H ALTADENA signal, was used for MFC experiments with magnetic field variation. Generally, these experiments were first performed with unsaturated precursors with natural abundance of 13C nuclei for the optimization of experimental parameters, and then MFC experiments were repeated with isotopically labeled precursors. This screening of substrates was performed in CD3OD solutions at 40 psig hydrogen pressure. Then the two precursors that provided the highest 1H and 13C polarizations were used in aqueous phase hydrogenation and for MRI demonstration in vitro.

PHIP of ethyl 1-13C-acetate.

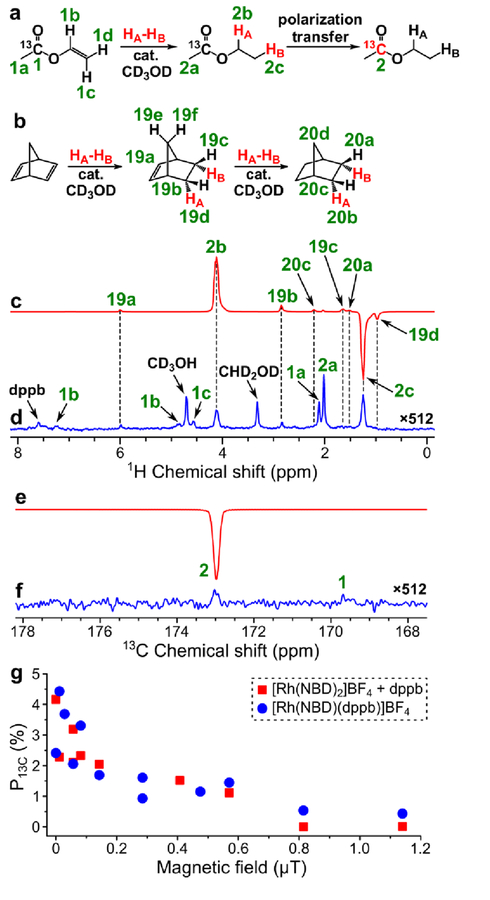

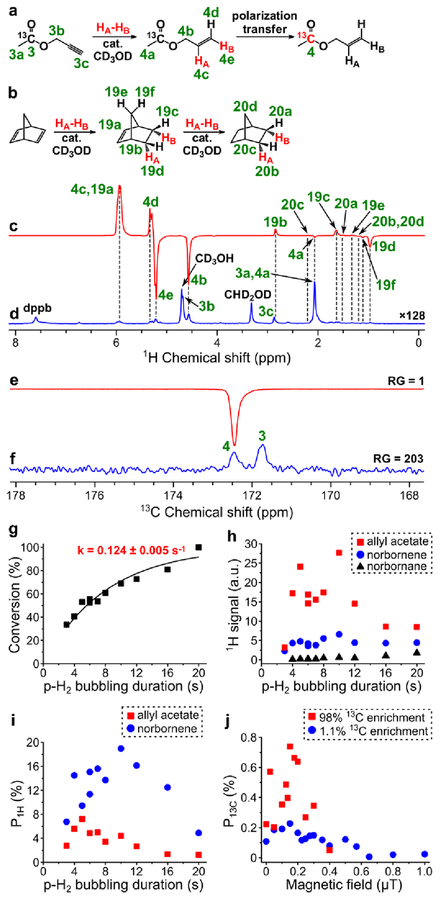

PHIP of ethyl 1-13C-acetate produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of vinyl 1-13C-acetate with p-H2 in CD3OD was reported previously.61 In that study, P1H = 3.3% and P13C = 1.8% were demonstrated at 50% p-H2 enrichment and 90 psig pressure. At 85% p-H2 enrichment, these polarizations would be 2.4 times higher,29 resulting in P1H = 7.9% and P13C = 4.3%. Similar polarization values were obtained in this work in a hyperpolarization protocol reproducibility test (average P1H = 7.5%, maximum P1H = 8.1%, recalculated to 85% p-H2 enrichment; see Figure 2c, Figure 2d and Table S1). Because vinyl acetate hydrogenation was studied in detail before,61 here we used this substrate to test the alternative experimental protocol for the sample preparation. Previous experiments employed commercially available [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst. In the alternative experimental protocol, the [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]+ species were formed during the sample preparation procedure from commercially available [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb in 1:1 ratio, and the resultant solution was used for PHIP experiments without any purification. Therefore, in the alternative experimental protocol the solution contains 2 equivalents of norbornadiene instead of 1 equivalent in the solution prepared from the commercially available [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 complex. On the other hand, the reactants required for the alternative experimental protocol are several times cheaper. The obtained results are presented in Figure 2. It was found that both variants of the experimental protocols have similar efficiency (see Figure 2g). Therefore, in further experiments reported here the catalyst was prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb. The maximum obtained P13C was 4.4% (at 85% p-H2 fraction), which is in a good agreement with the previously reported61 value despite the use of lower hydrogen pressure (40 psig instead of 90 psig; the polarization values are recalculated to 85% p-H2 enrichment).

Figure 2.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to vinyl 1-13C-acetate in CD3OD followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule, cat. = [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4). (b) Reaction scheme of the competing process of norbornadiene hydrogenation with p-H2. (c) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of ethyl acetate with 15 s p-H2 bubbling duration. (d) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 512). ε1H = 3750, P1H = 8.6% (8.1% at 85% p-H2 fraction). Note that spectra (c) and (d) were acquired on a 7.05 T NMR spectrometer. (e) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of ethyl 1-13C-acetate using MFC at near 0 μT magnetic field. (f) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 512). ε13C = 3560, P13C = 2.75% (4.2% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (g) Dependence of P13C (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of ethyl 1-13C-acetate on magnetic field used in MFC experiments (red squares – data points obtained with the [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb, blue circles – data points obtained with the commercial [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst).

PHIP of propyl 1-13C-acetate.

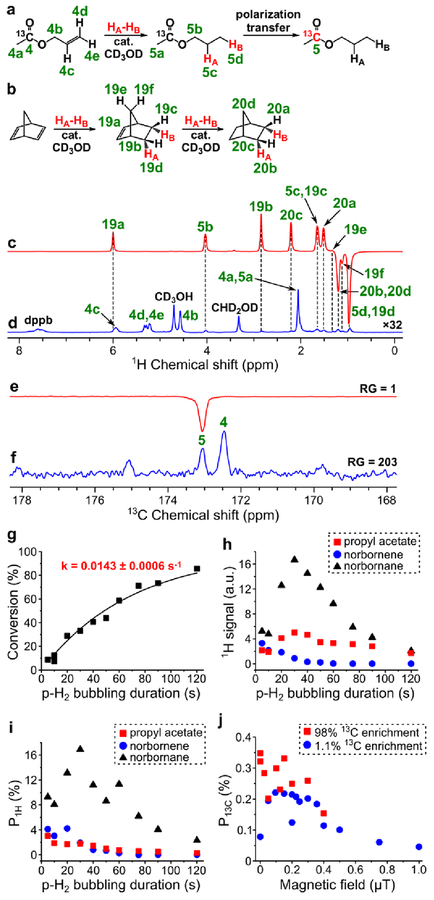

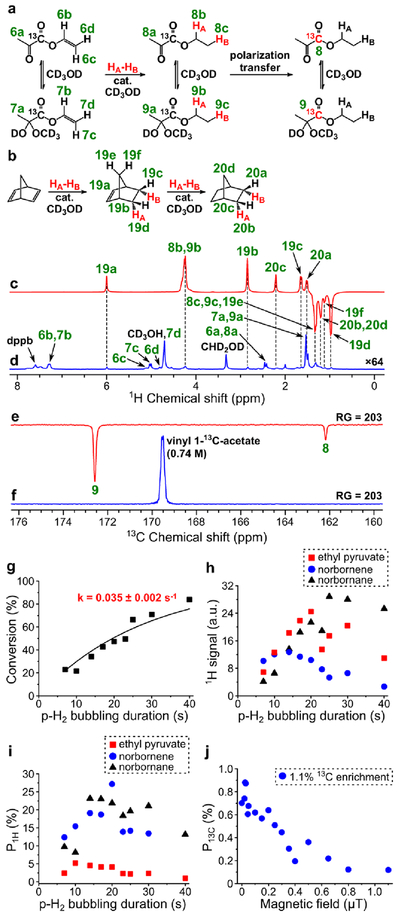

HP propyl acetate was produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of allyl acetate in methanol over [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb. According to 1H NMR, the catalyst activity was quite low, since 50% conversion of allyl acetate was reached only after ~50 s of hydrogen bubbling at 40 psig pressure (see Figure 3g). The estimation of 1H polarization values for propyl acetate was complicated, because 1H NMR signals 5c and 5d of propyl acetate overlapped with signals 19c and 19d of norbornene, respectively (see Figure 3c). Since it was not possible to reliably estimate the relative contribution of propyl acetate and norbornene protons to the observed ALTADENA signals, 1H polarization of propyl acetate was calculated on the basis of NMR signal 5b. The maximum obtained ALTADENA P1H of the corresponding protons of propyl acetate was 3.0% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 3i). Next, MFC experiments with magnetic field variation were performed at 30 s duration of p-H2 bubbling (at which the maximum 1H ALTADENA signal was observed). The maximum obtained P13C was 0.35% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 3e, Figure 3f, Figure 3j).

Figure 3.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to allyl 1-13C-acetate in CD3OD followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule, cat. = [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4). (b) Reaction scheme of the competing process of norbornadiene hydrogenation with p-H2. (c) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of propyl 1-13C-acetate with 5 s p-H2 bubbling duration. (d) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 32). ε1H = 630, P1H = 1.9% (3.0% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (e) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of propyl 1-13C-acetate using MFC at near 0 μT magnetic field with RG = 1. (f) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization with RG = 203. ε13C = 350, P13C = 0.27% (0.35% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (g) Dependence of conversion of allyl acetate to propyl acetate on p-H2 bubbling duration (estimated pseudo-first order rate constant k = 0.0143 ± 0.0006 s–1). (h) Dependence of 1H ALTADENA signal (absolute value) of HP propyl acetate (signal 5b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19b, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (i) Dependence of P1H (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of propyl acetate (signal 5b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19b, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (j) Dependence of P13C (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of propyl 1-13C-acetate on magnetic field used in MFC experiments (red squares – data points obtained with the 98% 13C-enriched precursor, blue circles – data points obtained with the 1.1% 13C-enriched precursor).

PHIP of allyl 1-13C-acetate.

HP allyl acetate was produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of propargyl acetate in methanol over [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb. The catalyst was significantly more active in hydrogenation of this compound than in hydrogenation of allyl acetate at the same conditions: 50% conversion of propargyl acetate was achieved after ~5.5 s of hydrogen bubbling at 40 psig pressure (see Figure 4g). Due to overlapping of 1H NMR signal 4c of allyl acetate with signal 19a of norbornene (see Figure 4c), 1H polarization of allyl acetate was calculated on the basis of NMR signal 4e. The maximum obtained ALTADENA P1H of the corresponding protons of allyl acetate was 7.2% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 4i). Next, MFC experiments with magnetic field variation were performed at 5 s duration of p-H2 bubbling (at which the maximum 1H ALTADENA signal was observed). The maximum obtained P13C was 0.74% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 4e, Figure 4f, Figure 4j).

Figure 4.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to propargyl 1-13C-acetate in CD3OD followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule, cat. = [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4). (b) Reaction scheme of the competing process of norbornadiene hydrogenation with p-H2. (c) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of allyl 1-13C-acetate with 5 s p-H2 bubbling duration. (d) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 128). ε1H = 2090, P1H = 6.4% (7.2% at 85% p-H2 fraction) (calculated using signal 4e). (e) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of allyl 1-13C-acetate using MFC at 0.15 μT magnetic field with RG = 1. (f) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization with RG = 203. ε13C = 580, P13C = 0.45% (0.74% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (g) Dependence of conversion of propargyl acetate to allyl acetate on p-H2 bubbling duration (estimated pseudo-first order rate constant k = 0.124 ± 0.005 s–1). (h) Dependence of 1H ALTADENA signal (absolute value) of HP allyl acetate (signal 4e, red squares), norbornene (signal 19d, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (i) Dependence of P1H (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of allyl acetate (signal 4e, red squares) and norbornene (signal 19d, blue circles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. P1H for norbornane is not presented because it cannot be estimated reliably due to low conversion of norbornadiene to norbornane. (j) Dependence of P13C (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of allyl 1-13C-acetate on magnetic field used in MFC experiments (red squares – data points obtained with the 98% 13C-enriched precursor, blue circles – data points obtained with the 1.1% 13C-enriched precursor).

PHIP of ethyl 1-13C-pyruvate.

HP ethyl pyruvate was produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of vinyl pyruvate in methanol over [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb. Importantly, both vinyl and ethyl pyruvate esters are present in two forms in methanolic solution (see Figure 5a). Hemiketal form is prevalent, while the contribution of ketone form is also quite substantial. However, because these two forms have similar 1H NMR chemical shifts for the protons of alcoholic moiety, calculations of conversion and P1H can be performed in the same way as for acetates using the total amounts of both forms of pyruvate esters. The catalyst activity was moderate: 50% conversion of vinyl pyruvate was achieved after ~20 s of hydrogen bubbling at 40 psig pressure (see Figure 5g). The maximum obtained ALTADENA P1H of ethyl pyruvate was 5.2% (at 85% p-H2 fraction), estimated on the basis of signal 8b+9b (Figure 5i). Since we do not have 13C-labeled vinyl pyruvate, MFC experiments were performed only with the substrate with natural abundance of 13C nuclei. For calculations of P13C for ethyl pyruvate, the sum of intensities of 13C PHIP NMR signals of ketone and hemiketal forms was used as the PHIP signal intensity I13C-PHIP, because it was not possible to estimate the ratio of these two forms of ethyl pyruvate using 1H NMR. The maximum obtained P13C was 0.88% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 5e, Figure 5f, Figure 5j). It should be noted that HP ethyl pyruvate is the only HP ester obtained in this study that was previously employed for metabolic imaging directly without preliminary hydrolysis.66 The use of HP ethyl pyruvate is especially advantageous for brain imaging due to its faster transport from blood to brain compared to HP pyruvate.66 The fact that ethyl pyruvate is used as a food additive and also has been studied as an anti-inflammatory compound makes it a promising HP molecule for the future use in clinic, despite the fact that it did not demonstrate high levels of polarization in our studies.

Figure 5.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to vinyl 1-13C-pyruvate in CD3OD followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule, cat. = [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4). (b) Reaction scheme of the competing process of norbornadiene hydrogenation with p-H2. (c) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of ethyl 1-13C-pyruvate with 10 s p-H2 bubbling duration. (d) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 64). ε1H = 1650, P1H = 5.1% (5.2% at 85% p-H2 fraction) (calculated using signal 8b+9b). (e) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of ethyl pyruvate (1.1% 13C enrichment) using MFC at 0.025 μT magnetic field with RG = 203 (p-H2 bubbling duration = 20 s). (f) 13C NMR spectrum of 0.74 M solution of vinyl 1-13C-acetate used as an external reference acquired with RG = 203. ε13C = 900, P13C = 0.70% (0.88% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (g) Dependence of conversion of vinyl pyruvate to ethyl pyruvate on p-H2 bubbling duration (estimated pseudo-first order rate constant k = 0.035 ± 0.002 s–1). (h) Dependence of 1H ALTADENA signal (absolute value) of HP ethyl pyruvate (signal 8b+9b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19d, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (i) Dependence of P1H (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of ethyl pyruvate (signal 8b+9b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19d, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (j) Dependence of P13C (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of ethyl pyruvate on magnetic field used in MFC experiments (data obtained with the 1.1% 13C-enriched precursor).

PHIP of propyl 1-13C-pyruvate.

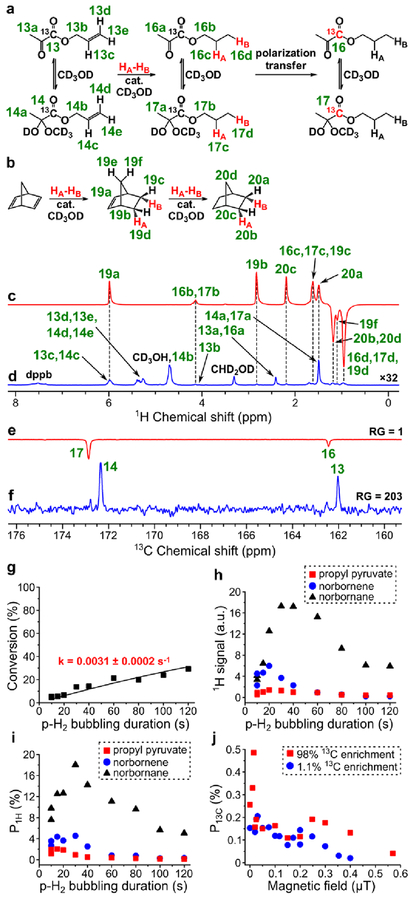

HP propyl pyruvate was produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of allyl pyruvate in methanol over [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb. Similar to vinyl and ethyl pyruvates, allyl and propyl pyruvates were present in hemiketal and ketone forms in methanolic solution with the prevalence of hemiketal form (see Figure 6a). These two forms also had similar 1H NMR chemical shifts for the protons of alcoholic moiety except protons 13b and 14b. Therefore, calculations of conversion and P1H were carried out using the total amounts of these two forms of pyruvates. The catalyst activity was very low: after 2 minutes of hydrogen bubbling at 40 psig pressure, the conversion of allyl pyruvate was only ~30% (see Figure 6g). Due to overlapping of 1H NMR signals 16c+17c and 16d+17d of propyl pyruvate with signals 19c and 19d of norbornene, respectively (see Figure 6c), 1H polarization of propyl pyruvate was calculated on the basis of NMR signal 16b+17b. The maximum obtained ALTADENA P1H of the corresponding protons of propyl pyruvate was 2.0% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 6i). Next, MFC experiments with magnetic field variation were performed at 20 s duration of p-H2 bubbling (at which the maximum 1H ALTADENA signal was observed). For calculations of P13C for propyl pyruvate with 13C nuclei at natural abundance, the sum of intensities of 13C PHIP NMR signals of ketone and hemiketal forms was used as the PHIP signal intensity I13C-PHIP, because it was not possible to estimate the ratio of these two forms of propyl pyruvate using 1H NMR. For calculations of P13C for 98% 13C-enriched propyl pyruvate we used the 13C PHIP NMR signals of the prevalent hemiketal form, because it was not possible to detect thermally polarized ketone form using 13C NMR in reasonable time (and sometimes it was also not possible to detect 13C PHIP NMR signals of ketone form). The maximum obtained P13C was 0.49% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 6e, Figure 6f, Figure 6j).

Figure 6.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to allyl 1-13C-pyruvate in CD3OD followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule, cat. = [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4). (b) Reaction scheme of the competing process of norbornadiene hydrogenation with p-H2. (c) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of propyl 1-13C-pyruvate with 15 s p-H2 bubbling duration. (d) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 32). ε1H = 480, P1H = 1.5% (2.0% at 85% p-H2 fraction) (calculated using signal 16b+17b). (e) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of propyl 1-13C-pyruvate using MFC at 0.015 μT magnetic field with RG = 1. (f) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization with RG = 203. ε13C = 610, P13C = 0.47% (0.49% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (g) Dependence of conversion of allyl pyruvate to propyl pyruvate on p-H2 bubbling duration (estimated pseudo-first order rate constant k = 0.0031 ± 0.0002 s–1). (h) Dependence of 1H ALTADENA signal (absolute value) of HP propyl pyruvate (signal 16b+17b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19b, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (i) Dependence of P1H (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of allyl acetate (signal 16b+17b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19b, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (j) Dependence of P13C (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of propyl 1-13C-pyruvate on magnetic field used in MFC experiments (red squares – data points obtained with the 98% 13C-enriched precursor, blue circles – data points obtained with the 1.1% 13C-enriched precursor).

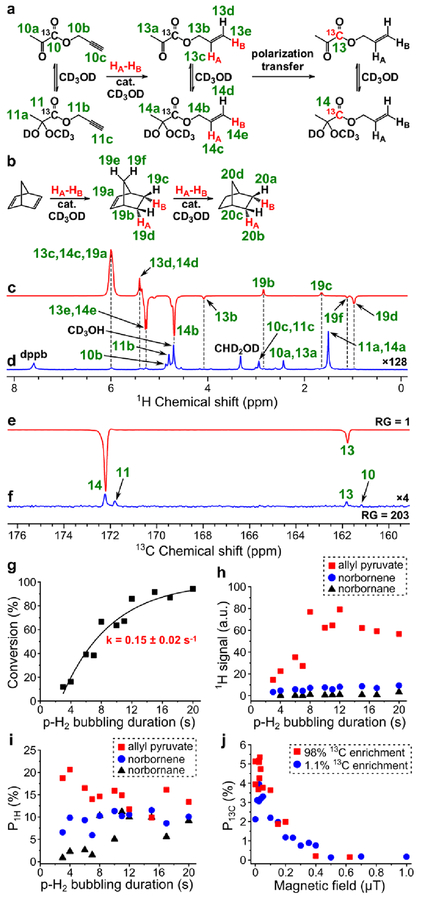

PHIP of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate.

HP allyl pyruvate was produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of propargyl pyruvate in methanol over [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4 catalyst prepared from [Rh(NBD)2]BF4 and dppb. Similar to other pyruvate esters, propargyl and allyl pyruvates were present in hemiketal and ketone forms in methanolic solution with the prevalence of hemiketal form (see Figure 7a). These two forms also had similar 1H NMR chemical shifts for the protons of alcoholic moiety except protons 13b and 14b. Therefore, calculations of conversion were carried out using the total amounts of these two forms of pyruvates. The catalyst demonstrated high activity: 50% conversion of propargyl pyruvate was achieved after ~7 s of p-H2 bubbling at 40 psig pressure (see Figure 7g). Due to overlapping of 1H NMR signal 13c+14c of allyl pyruvate with signal 19a of norbornene (see Figure 7c), 1H polarization of allyl pyruvate was calculated either on the basis of the NMR signal 13e+14e or on the basis of sum of NMR signals 13b and 14b, depending on what signals yielded the highest ε1H. The sum of signals 13b and 14b was used due to the fact that it was not possible to reliably estimate the ratio of hemiketal and ketone forms of allyl pyruvate using thermal spectra (signal 14b overlaps with the signal of the solvent and signal 13b is too weak). The maximum obtained ALTADENA P1H of the corresponding protons of allyl pyruvate was 21% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 7i). Next, MFC experiments with magnetic field variation were performed at 10 s duration of p-H2 bubbling. For calculations of P13C for allyl pyruvate with 13C nuclei at natural abundance, the sum of intensities of 13C PHIP NMR signals of ketone and hemiketal forms was used as the PHIP signal intensity I13C-PHIP, because it was not possible to estimate the ratio of these two forms of allyl pyruvate using 1H NMR. For calculations of P13C for 98% 13C-enriched allyl pyruvate we used the 13C PHIP NMR signals of the prevalent hemiketal form; the estimated ε13C values for ketone form were on average 1.5 times lower. The maximum obtained P13C was 5.4% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 7e, Figure 7f, Figure 7j).

Figure 7.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to propargyl 1-13C-pyruvate in CD3OD followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule, cat. = [Rh(NBD)(dppb)]BF4). (b) Reaction scheme of the competing process of norbornadiene hydrogenation with p-H2. (c) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate with 4 s p-H2 bubbling duration. (d) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 128). ε1H = 4320, P1H = 13% (21% at 85% p-H2 fraction) (calculated using sum of signals 13b and 14b). (e) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate using MFC at 0.030 μT magnetic field with RG = 1. (f) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization with RG = 203 (multiplied by a factor of 4). ε13C = 4340, P13C = 3.3% (5.4% at 85% p-H2 fraction). (g) Dependence of conversion of propargyl pyruvate to allyl pyruvate on p-H2 bubbling duration (estimated pseudo-first order rate constant k = 0.15 ± 0.02 s–1). (h) Dependence of 1H ALTADENA signal (absolute value) of HP allyl pyruvate (signal 14b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19d, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (i) Dependence of P1H (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of allyl pyruvate (signal 13e+14e or the sum of NMR signals 13b and 14b, red squares), norbornene (signal 19d, blue circles) and norbornane (signal 20b+20d or signal 20a, black triangles) on p-H2 bubbling duration. (j) Dependence of P13C (at 85% p-H2 fraction) of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate on magnetic field used in MFC experiments (red squares – data points obtained with the 98% 13C-enriched precursor, blue circles – data points obtained with the 1.1% 13C-enriched precursor).

PHIP of ethyl 1-13C-acetate and allyl 1-13C-pyruvate in aqueous phase.

In CD3OD solutions, the highest polarizations were observed for ethyl 1-13C-acetate and allyl 1-13C-pyruvate (for example, for these compounds P13C = 4.4% and 5.4%, respectively, were obtained while for other esters P13C were less than 1%). Therefore, these compounds were chosen as targets for hyperpolarization experiments in aqueous phase. These experiments employed water-soluble [Rh(NBD)(Ph((CH2)3SO3–)P–(CH2)4–PPh((CH2)3SO3–))]BF4 complex as a homogeneous hydrogenation catalyst. Due to generally lower efficiency of hydrogenation in aqueous phase,60 we used harsher experimental conditions (70–80 psig H2 pressure, 60–85 °C temperature and 140 sccm gas flow rate). Hydrogenation of vinyl acetate at 70 psig and 60 °C was highly efficient since 100% conversion of the reactant was achieved just after 7 s of p-H2 bubbling (see Table S2). The maximum obtained ALTADENA P1H of ethyl 1-13C-acetate was 5.7%, while P13C was 2.1% (both at 85% p-H2 fraction) (Figure 8). Hydrogenation of propargyl pyruvate was quite slow since after 20 s of p-H2 bubbling at 70 psig and 80 °C the conversion was only ~7% (see Table S3). ALTADENA P1H was lower than in case of vinyl acetate hydrogenation in aqueous phase (the maximum P1H = 3.6% at 85% p-H2 fraction, see Table S3). However, at 80 psig, 85 °C and ~10 mM catalyst concentration (instead of ~5.3 mM concentration used in other experiments in aqueous phase) P1H = 6.0% was obtained (at 85% p-H2 fraction) (see Figure 9). Moreover, PASADENA experiments were performed yielding P1H = 1.7% (at 85% p-H2 fraction) for HP allyl 1-13C-pyruvate (Figure S2). In MFC experiments with HP allyl 1-13C-pyruvate the maximum P13C was only 0.82% (at 85% p-H2 fraction), which is ~2.5 times lower than that obtained for ethyl 1-13C-acetate (Figure 9). Magnetic field profile of P13C for allyl 1-13C-pyruvate is presented in Figure S3. Thus, we demonstrate the feasibility of obtaining HP ethyl acetate and allyl pyruvate in aqueous solution using water-soluble hydrogenation catalyst.

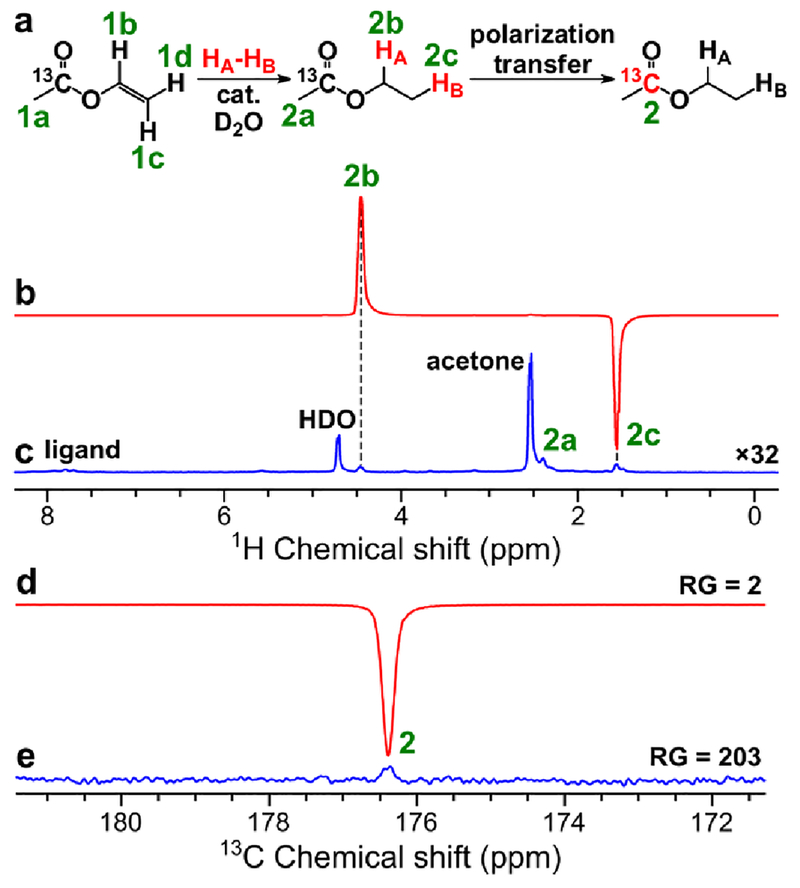

Figure 8.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to vinyl 1-13C-acetate in D2O over water-soluble Rh catalyst followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule). (b) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of ethyl 1-13C-acetate with 7 s p-H2 bubbling duration at 70 psig and 60 °C. (c) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 32). Acetone was used during sample preparation step.62 ε1H = 1680, P1H = 5.2% (5.3% at 85% p-H2 fraction) (calculated using signal 2b). (d) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of ethyl 1-13C-acetate using MFC at near 0 μT magnetic field with RG = 2 (p-H2 bubbling duration = 7 s at 70 psig and 60 °C). (e) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization with RG = 203. ε13C = 1550, P13C = 1.2% (2.1% at 85% p-H2 fraction).

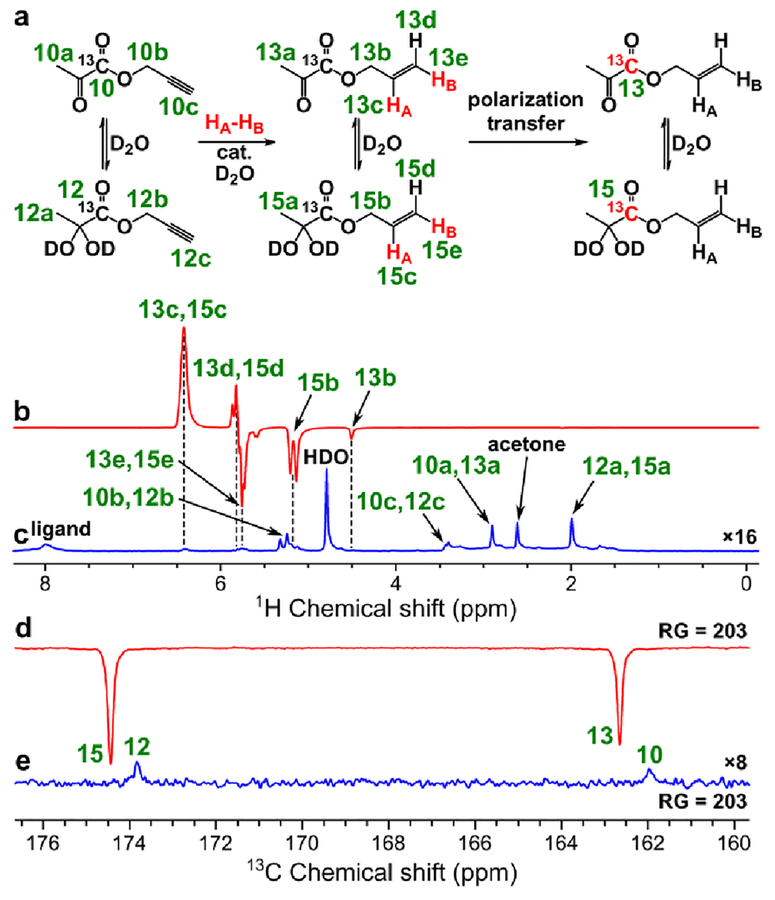

Figure 9.

(a) Reaction scheme of pairwise addition of p-H2 to propargyl 1-13C-pyruvate in D2O over water-soluble Rh catalyst followed by polarization transfer to 13C nuclei (HA and HB are two atoms from the same p-H2 molecule). (b) 1H NMR spectrum acquired after 1H ALTADENA hyperpolarization of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate with ~10 mM catalyst concentration and 30 s p-H2 bubbling duration at 80 psig and 85 °C. (c) Corresponding thermal 1H NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization (multiplied by a factor of 16). Acetone was used during sample preparation step.62 ε1H = 1090, P1H = 3.2% (6.0% at 85% p-H2 fraction) (calculated using signal 13c+15c). (d) 13C NMR spectrum acquired after 13C hyperpolarization of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate using MFC at 0.025 μT magnetic field with ~5.3 mM catalyst concentration and 20 s p-H2 bubbling duration at 70 psig and 80 °C. (e) Corresponding thermal 13C NMR spectrum acquired after relaxation of hyperpolarization. ε13C = 760, P13C = 0.55% (0.82% at 85% p-H2 fraction).

Efficiency of homogeneous PHIP of acetate and pyruvate esters.

The summary of PHIP results for the six esters under study is presented in Table 1. Propyl acetate and propyl pyruvate were found to be the two least efficiently hyperpolarized compounds. From acetate esters, ethyl acetate was found to be the most efficiently hyperpolarized one, with up to 4.4% 13C polarization in methanol. In contrast, allyl pyruvate hyperpolarization was more efficient than that of ethyl pyruvate, with up to 21% 1H and up to 5.4% 13C polarization in methanol. The attainable 1H and 13C polarizations clearly qualitatively correlate well with the hydrogenation rate constants (see Table 1). The highest polarizations were obtained in cases when unsaturated precursors are hydrogenated faster. This result can be explained by the fact that the observed PHIP signal is proportional to both concentration and nuclear spin polarization of the hydrogenation product. While concentration increases with reaction time, polarization decreases simultaneously because of the nuclear spin relaxation. This means that the dependence of PHIP signal intensity on reaction time should have a maximum. The slower is hydrogenation reaction, the longer is the reaction time at which PHIP signal intensity reaches this maximum,67 and the lower are polarization and PHIP signal intensity at this maximum due to disproportionately greater relaxation effects of 1H HP state depolarization. Future catalyst development is certainly warranted for the compounds that react too slowly. The alternative approach is the employment of reaction conditions with elevated temperature and p-H2 pressure, which can be achieved by the use of more efficient PHIP polarizer setups.68,69 It should be noted that 1H relaxation is significantly faster than 13C relaxation – T1 at 9.4 T is on the order of several seconds for 1H and on the order of several tens of seconds for 13C nuclei (for example, for protons of allylic CH2 group of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate (signal 13b in Figure 7) T1 = 7.8 ± 0.4 s, while for 13C nuclei of the same compound T1 = 35 ± 1 s in case of ketone form and T1 = 38 ± 4 s in case of hemiketal form). Since the time required for transfer of the sample to the NMR spectrometer after the field cycling was relatively short (~2 s), 13C relaxation has a minor effect on the observed P13C. On the other hand, the effect of 1H relaxation is dramatic, since the reaction time was on the order of relaxation time or several times larger depending on the substrate.64 Therefore, minimization of reaction time is certainly warranted for achieving higher 13C polarizations. Another factor that is important to optimize is the polarization transfer efficiency. In our experiments, polarization transfer efficiency did not exceed 54%, which is ~1.3 times lower than that achieved by Cavallari et al. for allyl pyruvate using MFC approach.55 Therefore, design of a better MFC hardware is also warranted for achieving higher 13C polarizations.33

Table 1.

Summary of the Results Obtained in Homogeneous PHIP of Acetate and Pyruvate Esters: Pseudo-First Order Rate Constants, Maximal 1H and 13C PHIP Signal Intensities and Polarizations (at 85% p-H2 fraction), and Polarization Transfer Efficiency (η).

| HP ester | Solvent | k, s–1 | maximal 1H PHIP signal, a.u. | maximal 13C PHIP signal, a.u.a | maximal P1H, % | maximal P13C, % | η, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl acetate | CD3OD | not estimated | not estimated | 34 | 8.1 | 4.4 | 54 |

| Propyl acetate | CD3OD | 0.0143 ± 0.0006 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 0.35 | 12 |

| Allyl acetate | CD3OD | 0.124 ± 0.005 | 19 | 6.4 | 7.2 | 0.74 | 10 |

| Ethyl pyruvate | CD3OD | 0.035 ± 0.002 | 17 | 27 | 5.2 | 0.88 | 17 |

| Propyl pyruvate | CD3OD | 0.0031 ± 0.0002 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.49 | 24 |

| Allyl pyruvate | CD3OD | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 64 | 96 | 21 | 5.4 | 26 |

| Ethyl acetate | D2O | not estimated | 9.6 | 8.4 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 36 |

| Allyl pyruvate | D2O | not estimated | 3.6 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 0.82 | 23 |

These values were calculated taking into account the differences in 13C enrichment and NMR acquisition parameters used in different experiments.

13C MRI in vitro.

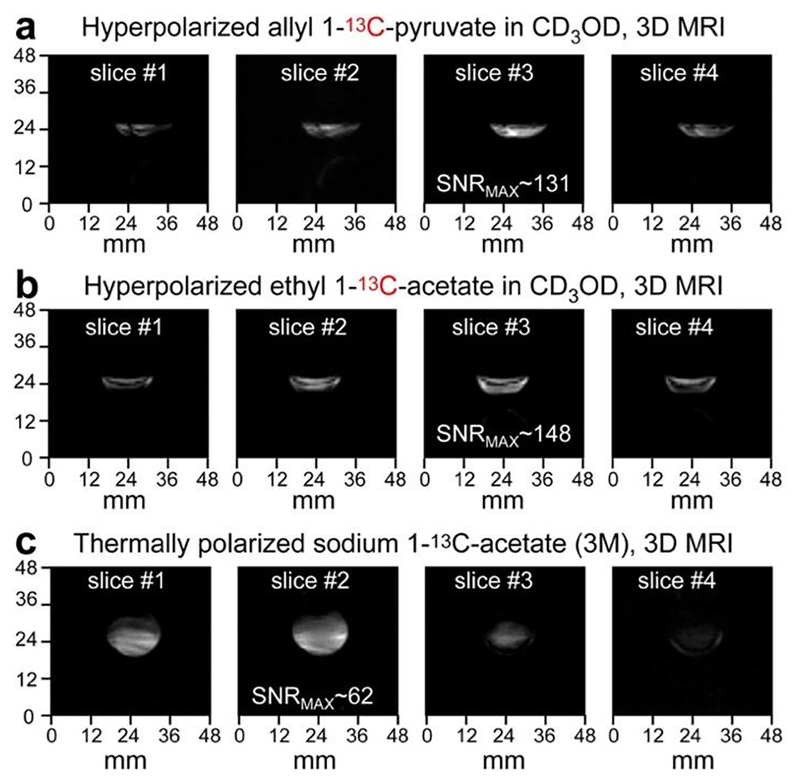

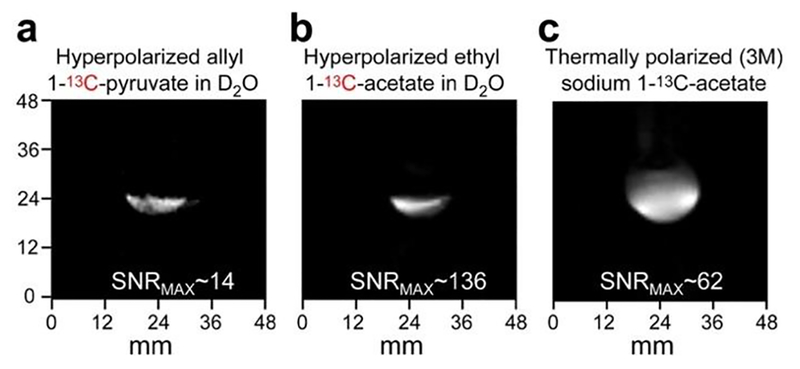

Feasibility of the utilization of obtained HP acetates and pyruvates for 13C MRI was demonstrated on the example of ethyl 1-13C-acetate and allyl 1-13C-pyruvate, which showed the highest levels of polarization. 2D projections of 3D 13C MR images of the 80 mM methanolic solutions of these compounds in a hollow spherical phantom are presented in Figure 10. The maximum SNR values in these images were more than 2 times higher than that obtained in MRI of 3 M solution of thermally polarized sodium 1-13C-acetate in the same phantom despite the ~40-fold difference in concentrations. We have also performed 2D 13C MRI of aqueous solutions of HP ethyl 1-13C-acetate and allyl 1-13C-pyruvate produced by homogeneous hydrogenation of corresponding unsaturated precursors with p-H2 over water-soluble rhodium catalyst (see Figure 11). As expected from data presented in Table 1, SNR for allyl 1-13C-pyruvate in aqueous solution was significantly lower than that obtained for the same compound in methanol. On the other hand, SNR for ethyl 1-13C-acetate were similar for both solvents. These results clearly show the prospects for utilization of 13C HP ethyl 1-13C-acetate and allyl 1-13C-pyruvate as molecular contrast agents for in vivo use and ultimately clinical MRI use. Moreover, the obtained 13C HP esters can be cleaved using alkaline hydrolysis, resulting in formation of 13C HP carboxylates.53 Though we did not perform such experiments in this work, we do not anticipate significant challenges with removal of sidearm in any of the molecules studied here, based on the work of others and our own experience. For example, Reineri et al. successfully obtained hyperpolarized acetate and pyruvate by removing sidearm in ethyl acetate and allyl pyruvate, respectively.53 Later the same team has obtained HP lactate by hydrolysis of HP allyl lactate ester.54 Moreover, Korchak et al. used the same approach to cleave cinnamyl acetate and cinnamyl pyruvate.59 Given these multiple examples, the ester structure does not significantly influence the possibility of successful ester hydrolysis on the desired time scale for preserving 13C HP state. Furthermore, our own experience with hydrolysis of ethyl acetate is that this reaction proceeds rapidly and quantitatively.51 Therefore, we expect that removal of side arm in ethyl pyruvate, propyl acetate, propyl pyruvate and allyl acetate should also be feasible and efficient.

Figure 10.

2D projections of 3D 13C MR images of: (a) HP allyl 1-13C-pyruvate solution in CD3OD produced via pairwise addition of p-H2 to propargyl 1-13C-pyruvate (80 mM), (b) HP ethyl 1-13C-acetate in CD3OD produced via pairwise addition of p-H2 to vinyl 1-13C-acetate (80 mM), (c) 3 M aqueous solution of thermally polarized sodium 1-13C-acetate (signal reference phantom). The phantoms represented hollow spherical balls (~2.8 mL volume) with solutions located in the bottom. The double image in display (a) is due to two HP species present with two distinctly different chemical shifts (see Figure 7 for more details).

Figure 11.

2D 13C MR images of: (a) HP allyl 1-13C-pyruvate produced via pairwise addition of p-H2 to propargyl 1-13C-pyruvate in D2O, (b) HP ethyl 1-13C-acetate produced via pairwise addition of p-H2 to vinyl 1-13C-acetate in D2O, (c) 3 M solution of thermally polarized sodium 1-13C-acetate (signal reference phantom). The double image in display (a) is due to two HP species present with two distinctly different chemical shifts (see Figure 9 for more details).

CONCLUSIONS

Acetate and pyruvate esters with ethyl, propyl and allyl alcoholic moieties were successfully hyperpolarized using homogeneous hydrogenation of the corresponding unsaturated precursors in CD3OD with parahydrogen. Polarization transfer from 1H to 13C nuclei was performed using magnetic field cycling. It was found that the polarization of obtained HP state strongly depends on the rate of hydrogenation. The highest polarizations (21% for 1H and 5.4% for 13C nuclei) were obtained for allyl pyruvate produced by hydrogenation of propargyl pyruvate, the most readily hydrogenated compound among those under study. Allyl pyruvate and ethyl acetate were also hyperpolarized using hydrogenation with parahydrogen in the aqueous phase over water-soluble homogeneous rhodium catalyst, yielding 0.82% and 2.1% 13C polarization, respectively. Feasibility of utilization of the obtained 13C-hyperpolarized compounds for MRI was demonstrated on the example of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate and ethyl 1-13C-acetate. 3D 13C MR images with SNR ~131 and ~148, respectively, were obtained for methanolic solutions of these compounds. 2D 13C MRI visualization of aqueous solutions of allyl 1-13C-pyruvate and ethyl 1-13C-acetate was also carried out. This systematic study will guide the future development of the PHIP-SAH hyperpolarization in terms of the optimization of catalysts, hyperpolarization hardware and experimental protocols.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

K.V.K., O.G.S. and N.V.C. thank RSF (17-73-20030) for the support of synthesis of labeled compounds. I.V.K. thanks the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education for financial support. US team thanks the following support for funding: by NSF under grants CHE-1416268, and CHE-1836308, by the National Cancer Institute under 1R21CA220137, and by DOD CDMRP under BRP W81XWH-12-1-0159/BC112431 and under W81XWH-15-1-0271, and by RFBR under grant 17-54-33037 OHKO_a.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Structures of all compounds employed in this study, additional tables, graphs and NMR spectra (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Nikolaou P; Goodson BM; Chekmenev EY NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques for Biomedicine. Chem. - Eur. J 2015, 21, 3156–3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kovtunov KV; Pokochueva EV; Salnikov OG; Cousin SF; Kurzbach D; Vuichoud B; Jannin S; Chekmenev EY; Goodson BM; Barskiy DA, et al. Hyperpolarized NMR Spectroscopy: d-DNP, PHIP, and SABRE Techniques. Chem. - Asian J 2018, 13, 1857–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Dumez J-N Perspectives on Hyperpolarised Solution-State Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry. Magn. Reson. Chem 2017, 55, 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Barskiy DA; Coffey AM; Nikolaou P; Mikhaylov DM; Goodson BM; Branca RT; Lu GJ; Shapiro MG; Telkki V-V; Zhivonitko VV, et al. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques of Gases. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 725–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Skinner JG; Menichetti L; Flori A; Dost A; Schmidt AB; Plaumann M; Gallagher FA; Hövener J-B Metabolic and Molecular Imaging with Hyperpolarised Tracers. Mol. Imaging Biol 2018, 20, 902–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Golman K; in ‘t Zandt R; Thaning M Real-Time Metabolic Imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 11270–11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Harrison C; Yang C; Jindal A; DeBerardinis RJ; Hooshyar MA; Merritt M; Sherry AD; Malloy CR Comparison of Kinetic Models for Analysis of Pyruvate-to-Lactate Exchange by Hyperpolarized 13C NMR. NMR Biomed. 2012, 25, 1286–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Liberti MV; Locasale JW The Warburg Effect: How Does It Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem. Sci 2016, 41, 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Golman K; in’t Zandt R; Lerche M; Pehrson R; Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH Metabolic Imaging by Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Imaging for In Vivo Tumor Diagnosis. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10855–10860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Brindle KM; Bohndiek SE; Gallagher FA; Kettunen MI Tumor Imaging Using Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med 2011, 66, 505–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Albers MJ; Bok R; Chen AP; Cunningham CH; Zierhut ML; Zhang VY; Kohler SJ; Tropp J; Hurd RE; Yen Y-F, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C Lactate, Pyruvate, and Alanine: Noninvasive Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Detection and Grading. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8607–8615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Day SE; Kettunen MI; Gallagher FA; Hu D-E; Lerche M; Wolber J; Golman K; Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH; Brindle KM Detecting Tumor Response to Treatment Using Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy. Nat. Med 2007, 13, 1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Park I; Bok R; Ozawa T; Phillips JJ; James CD; Vigneron DB; Ronen SM; Nelson SJ Detection of Early Response to Temozolomide Treatment in Brain Tumors Using Hyperpolarized 13C MR Metabolic Imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2011, 33, 1284–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Nelson SJ; Kurhanewicz J; Vigneron DB; Larson PEZ; Harzstark AL; Ferrone M; van Criekinge M; Chang JW; Bok R; Park I, et al. Metabolic Imaging of Patients with Prostate Cancer Using Hyperpolarized [1–13C]Pyruvate. Sci. Transl. Med 2013, 5, 198ra108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kurhanewicz J; Vigneron DB; Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH; Bankson JA; Brindle K; Cunningham CH; Gallagher FA; Keshari KR; Kjaer A; Laustsen C, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI: Path to Clinical Translation in Oncology. Neoplasia 2019, 21, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lai M; Gruetter R; Lanz B Progress towards in Vivo Brain 13C-MRS in Mice: Metabolic Flux Analysis in Small Tissue Volumes. Anal. Biochem 2017, 529, 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Morris P; Bachelard H Reflections on the Application of 13C-MRS to Research on Brain Metabolism. NMR Biomed. 2003, 16, 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Jensen PR; Peitersen T; Karlsson M; in ‘t Zandt R; Gisselsson A; Hansson G; Meier S; Lerche MH Tissue-Specific Short Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism and Slow Metabolic Recovery after Ischemia from Hyperpolarized NMR in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem 2009, 284, 36077–36082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mikkelsen EFR; Mariager CØ; Nørlinger T; Qi H; Schulte RF; Jakobsen S; Frøkiær J; Pedersen M; Stødkilde-Jørgensen H; Laustsen C Hyperpolarized [1–13C]-Acetate Renal Metabolic Clearance Rate Mapping. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 16002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bastiaansen JAM; Cheng T; Mishkovsky M; Duarte JMN; Comment A; Gruetter R In Vivo Enzymatic Activity of AcetylCoA Synthetase in Skeletal Muscle Revealed by 13C Turnover from Hyperpolarized [1–13C]Acetate to [1–13C]Acetylcarnitine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 4171–4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kurhanewicz J; Vigneron DB; Brindle K; Chekmenev EY; Comment A; Cunningham CH; DeBerardinis RJ; Green GG; Leach MO; Rajan SS, et al. Analysis of Cancer Metabolism by Imaging Hyperpolarized Nuclei: Prospects for Translation to Clinical Research. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 81–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ardenkjær-Larsen JH; Fridlund B; Gram A; Hansson G; Hansson L; Lerche MH; Servin R; Thaning M; Golman K Increase in Signal-to-Noise Ratio of >10,000 Times in Liquid-State NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2003, 100, 10158–10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH On the Present and Future of Dissolution-DNP. J. Magn. Reson 2016, 264, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Niedbalski P; Kiswandhi A; Parish C; Wang Q; Khashami F; Lumata L NMR Spectroscopy Unchained: Attaining the Highest Signal Enhancements in Dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2018, 9, 5481–5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bowers CR; Weitekamp DP Parahydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 5541–5542. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Eisenschmid TC; Kirss RU; Deutsch PP; Hommeltoft SI; Eisenberg R; Bargon J; Lawler RG; Balch AL Para Hydrogen Induced Polarization in Hydrogenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 8089–8091. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hövener J-B; Pravdivtsev AN; Kidd B; Bowers CR; Glöggler S; Kovtunov KV; Plaumann M; Katz-Brull R; Buckenmaier K; Jerschow A, et al. Parahydrogen-Based Hyperpolarization for Biomedicine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 11140–11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Green RA; Adams RW; Duckett SB; Mewis RE; Williamson DC; Green GGR The Theory and Practice of Hyperpolarization in Magnetic Resonance Using Parahydrogen. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc 2012, 67, 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bowers CR Sensitivity Enhancement Utilizing Parahydrogen. eMagRes 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bowers CR; Weitekamp DP Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical Reaction and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett 1986, 57, 2645–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Barkemeyer J; Haake M; Bargon J Hetero-NMR Enhancement via Parahydrogen Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 2927–2928. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kuhn LT; Bommerich U; Bargon J Transfer of Parahydrogen-Induced Hyperpolarization to 19F. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 3521–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Jóhannesson H; Axelsson O; Karlsson M Transfer of Para-Hydrogen Spin Order into Polarization by Diabatic Field Cycling. C. R. Physique 2004, 5, 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Boi T; Aime S; Reineri F Effects of Magnetic Field Cycle on the Polarization Transfer from Parahydrogen to Heteronuclei through Long-Range J-Couplings. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 10035–10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bär S; Lange T; Leibfritz D; Hennig J; von Elverfeldt D; Hövener J-B On the Spin Order Transfer from Parahydrogen to Another Nucleus. J. Magn. Reson 2012, 225, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Haake M; Natterer J; Bargon J Efficient NMR Pulse Sequences to Transfer the Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization to Hetero Nuclei. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 8688–8691. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Stevanato G Alternating Delays Achieve Polarization Transfer (ADAPT) to Heteronuclei in PHIP Experiments. J. Magn. Reson 2017, 274, 148–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Stevanato G; Eills J; Bengs C; Pileio G A Pulse Sequence for Singlet to Heteronuclear Magnetization Transfer: S2hM. J. Magn. Reson 2017, 277, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pravdivtsev AN; Yurkovskaya AV; Lukzen NN; Ivanov KL; Vieth H-M Highly Efficient Polarization of Spin-1/2 Insensitive NMR Nuclei by Adiabatic Passage through Level Anticrossings. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2014, 5, 3421–3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Golman K; Axelsson O; Jóhannesson H; Månsson S; Olofsson C; Petersson JS Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Imaging: Subsecond 13C Angiography. Magn. Reson. Med 2001, 46, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Bhattacharya P; Harris K; Lin AP; Mansson M; Norton VA; Perman WH; Weitekamp DP; Ross BD Ultra-Fast Three Dimensional Imaging of Hyperpolarized 13C in Vivo. MAGMA 2005, 18, 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Olsson LE; Chai C-M; Axelsson O; Karlsson M; Golman K; Petersson JS MR Coronary Angiography in Pigs With Intraarterial Injections of a Hyperpolarized 13C Substance. Magn. Reson. Med 2006, 55, 731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bhattacharya P; Chekmenev EY; Perman WH; Harris KC; Lin AP; Norton VA; Tan CT; Ross BD; Weitekamp DP Towards Hyperpolarized 13C-Succinate Imaging of Brain Cancer. J. Magn. Reson 2007, 186, 150–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Bhattacharya P; Chekmenev EY; Reynolds WF; Wagner S; Zacharias N; Chan HR; Bünger R; Ross BD Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization (PHIP) Hyperpolarized MR Receptor Imaging in Vivo: A Pilot Study of 13C Imaging of Atheroma in Mice. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zacharias NM; Chan HR; Sailasuta N; Ross BD; Bhattacharya P Real-Time Molecular Imaging of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolism in Vivo by Hyperpolarized 1–13C Diethyl Succinate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Schmidt AB; Berner S; Braig M; Zimmermann M; Hennig J; von Elverfeldt D; Hövener J-B In Vivo 13C-MRI Using SAMBADENA. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0200141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Buljubasich L; Franzoni MB; Münnemann K Parahydrogen Induced Polarization by Homogeneous Catalysis: Theory and Applications. Top. Curr. Chem 2013, 338, 33–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Kovtunov KV; Zhivonitko VV; Skovpin IV; Barskiy DA; Koptyug IV Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Catalytic Processes. Top. Curr. Chem 2013, 338, 123–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Kovtunov KV; Barskiy DA; Shchepin RV; Salnikov OG; Prosvirin IP; Bukhtiyarov AV; Kovtunova LM; Bukhtiyarov VI; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY Production of Pure Aqueous 13C-Hyperpolarized Acetate Via Heterogeneous Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization. Chem. - Eur. J 2016, 22, 16446–16449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kovtunov KV; Barskiy DA; Salnikov OG; Shchepin RV; Coffey AM; Kovtunova LM; Bukhtiyarov VI; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY Toward Production of Pure 13C Hyperpolarized Metabolites Using Heterogeneous Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization of Ethyl [1–13C]Acetate. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 69728–69732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Salnikov OG; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV Production of Catalyst-Free Hyperpolarised Ethanol Aqueous Solution via Heterogeneous Hydrogenation with Parahydrogen. Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 13930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Reineri F; Viale A; Ellena S; Boi T; Daniele V; Gobetto R; Aime S Use of Labile Precursors for the Generation of Hyperpolarized Molecules from Hydrogenation with Parahydrogen and Aqueous-Phase Extraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 7350–7353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Reineri F; Boi T; Aime S ParaHydrogen Induced Polarization of 13C Carboxylate Resonance in Acetate and Pyruvate. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Aime S; Reineri F 13C MR Hyperpolarization of Lactate by Using ParaHydrogen and Metabolic Transformation in Vitro. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 1200–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Aime S; Reineri F Studies to Enhance the Hyperpolarization Level in PHIP-SAH-Produced C13-Pyruvate. J. Magn. Reson 2018, 289, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Sorge M; Bonne G; Muchir A; Aime S; Reineri F The 13C Hyperpolarized Pyruvate Generated by ParaHydrogen Detects the Response of the Heart to Altered Metabolism in Real Time. Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 8366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Aime S; Reineri F Metabolic Studies of Tumor Cells Using [1–13C] Pyruvate Hyperpolarized by Means of PHIP-Side Arm Hydrogenation. ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Korchak S; Mamone S; Glöggler S Over 50% 1H and 13C Polarization for Generating Hyperpolarized Metabolites—A Para-Hydrogen Approach. ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 672–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Korchak S; Yang S; Mamone S; Glöggler S Pulsed Magnetic Resonance to Signal-Enhance Metabolites within Seconds by Utilizing Para-Hydrogen. ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Chukanov NV; Salnikov OG; Shchepin RV; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY Synthesis of Unsaturated Precursors for Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization and Molecular Imaging of 1–13C-Acetates and 1–13C-Pyruvates via Side Arm Hydrogenation. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6673–6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Shchepin RV; Barskiy DA; Coffey AM; Manzanera Esteve IV; Chekmenev EY Efficient Synthesis of Molecular Precursors for Para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization of Ethyl Acetate-1–13C and Beyond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 6071–6074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Cai C; Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Chekmenev EY; Waddell KW Efficient Transformation of Parahydrogen Spin Order into Heteronuclear Magnetization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 1219–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Pravica MG; Weitekamp DP Net NMR Alignment by Adiabatic Transport of Parahydrogen Addition Products to High Magnetic Field. Chem. Phys. Lett 1988, 145, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Salnikov OG; Shchepin RV; Chukanov NV; Jaigirdar L; Pham W; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY Effects of Deuteration of 13C‑Enriched Phospholactate on Efficiency of Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization by Magnetic Field Cycling. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 24740–24749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Mo H; Harwood JS; Raftery D Receiver Gain Function: The Actual NMR Receiver Gain. Magn. Reson. Chem 2010, 48, 235–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Hurd RE; Yen Y-F; Mayer D; Chen A; Wilson D; Kohler S; Bok R; Vigneron D; Kurhanewicz J; Tropp J, et al. Metabolic Imaging in the Anesthetized Rat Brain Using Hyperpolarized [1–13C] Pyruvate and [1–13C] Ethyl Pyruvate. Magn. Reson. Med 2010, 63, 1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Barskiy DA; Salnikov OG; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV NMR Signal Enhancement for Hyperpolarized Fluids Continuously Generated in Hydrogenation Reactions with Parahydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 996–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Truong ML; Wilkens K; Pham W; Chekmenev EY Open-Source Automated Parahydrogen Hyperpolarizer for Molecular Imaging Using 13C Metabolic Contrast Agents. Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 8279–8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Waddell KW; Coffey AM; Chekmenev EY In Situ Detection of PHIP at 48 mT: Demonstration Using a Centrally Controlled Polarizer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.