Abstract

Background

Balance impairments are common in patients with infratentorial stroke. Although robot-assisted gait training (RAGT) exerts positive effects on balance among patients with stroke, it remains unclear whether such training is superior to conventional physical therapy (CPT). Therefore, we aimed to investigate the effects of RAGT combined with CPT and compared them with the effects of CPT only on balance and lower extremity function among survivors of infratentorial stroke.

Methods

This study was a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial with a crossover design conducted at a single rehabilitation hospital. Patients (n = 19; 16 men, three women; mean age: 47.4 ± 11.6 years) with infratentorial stroke were randomly allocated to either group A (4 weeks of RAGT+CPT, followed by 4 weeks of CPT+CPT) or group B (4 weeks of CPT+CPT followed by 4 weeks of RAGT+CPT). Changes in dynamic and static balance as indicated by Berg Balance Scale scores were regarded as the primary outcome measure. Outcome measures were evaluated for each participant at baseline and after each 4-week intervention period.

Results

No significant differences in outcome-related variables were observed between group A and B at baseline. In addition, no significant time-by-group interactions were observed for any variables, indicating that intervention order had no effect on lower extremity function or balance. Significantly greater improvements in secondary functional outcomes such as lower extremity Fugl-Meyer assessment (FMA-LE) and scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) were observed following the RAGT+CPT intervention than following the CPT+CPT intervention.

Conclusion

RAGT produces clinically significant improvements in balance and lower extremity function in individuals with infratentorial stroke. Thus, RAGT may be useful for patients with balance impairments secondary to other pathologies.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02680691. Registered 09 February 2016; retrospectively registered.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12984-019-0553-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Robot-assisted gait training, Stroke, Balance, Gait impairment

Background

Balance impairments are common following stroke, often resulting in poor recovery of mobility and inability to perform activities of daily living unassisted. Such impairments represent a major risk factor for falls, which can lead to injury or death [1]. Although various interventions improve balance outcomes following stroke, no such intervention has been established as superior to others [2].

Balance impairments are a major concern in patients with infratentorial stroke, which accounts for 15–20% of all stroke cases [3, 4]. Infratentorial stroke is defined as stroke occurring below the tentorium cerebelli (including the cerebellum and brainstem), which is supplied by the vertebrobasilar artery. Common infratentorial posterior circulation symptoms include visual disturbance, vertigo, and ataxia [5]. The brainstem includes several cranial nuclei and relay pathways associated with eye movement, vestibular and somatosensory functions, and motor execution. The cerebellum plays a well-established role in modulating motor control, and brainstem dysfunction includes ataxia, dysdiadochokinesia, dysmetria, dysarthria, diplopia, and dysphagia [6, 7]. The cerebellum also contributes to the control of equilibrium and interlimb coordination during locomotion [8, 9]. A previous study suggests that the injury of infratentorial areas negatively affect balance functions [10]. Thus, balance impairments are common in patients with infratentorial stroke due to impaired integration of sensory information, postural control, and muscle strength.

Recently, the use of robot-assisted gait training (RAGT) for regaining and improving walking ability has increased among survivors of stroke [11]. During RAGT, the patient is placed in a supportive harness, and a robotic exoskeleton is attached to their lower extremities. The exoskeleton enables the application of guidance force provided by the robotic-orthosis during ambulation, thus allowing patients to engage in repeated practice of complex gait patterns at near-normal speed over a longer period. RAGT may enable practice enough to induce reorganization [12]. In conjunction with conventional physical therapy (CPT), it may result in significantly greater improvements in locomotor function than CPT alone [13].

In addition to providing both visual feedback and motor input for patients with stroke, RAGT is known to exert positive effects on balance [13–21]. However, it remains unclear whether RAGT results in greater improvements in balance than CPT [22]. While subsequent studies confirmed that RAGT results in favorable balance outcomes in patients with supratentorial stroke [23, 24], most studies have excluded patients with infratentorial stroke [16–21]. Because infratentorial stroke involves lesion in the cerebellum and the brainstem, it does not show the typical pattern of a supratentorial stroke. Indeed, to our knowledge, no studies have specifically investigated the effects of RAGT on balance among survivors of infratentorial stroke. Patients with infratentorial stroke often exhibit balance impairment because of eye movement impairment, vestibular functional deficits, vertigo, dizziness, and coordination deficits including ataxia, dysmetria, and dysdiadochokinesia other than motor weakness [25]. The infratentorial region including the cerebellum and brainstem is a pathway of the anterior corticospinal tract, tectospinal tract, vestibulospinal tract, and reticulospinal tract, which plays a role in balance; however, motor planning involving the supplementary motor area and premotor cortex is intact.

Therefore, this study aimed to compare the effects of RAGT combined with CPT and CPT only on balance function among survivors of infratentorial stroke. Given the lack of evidence regarding the use of RAGT in patients with infratentorial stroke, this study aimed to examine the effects of RAGT on balance function in this population. Our main hypothesis was that RAGT combined with CPT would produce clinically greater improvements in balance function than CPT only in individuals with infratentorial stroke.

Methods

This single-blinded, randomized controlled trial with a crossover design was conducted at the National Rehabilitation Center in Korea. Participants were recruited from among patients who had been admitted to the stroke inpatient rehabilitation unit of the hospital from February 2015 to January 2017. Participants were still inpatients at the time of training. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: chief complaint of balance deficits rather than motor weakness following infratentorial stroke, no history of prior stroke, age > 19 years, and an absence of cognitive deficits that would interfere with the patient’s understanding and cooperation with instructions provided by the investigator (i.e., Mini-Mental State Examination score > 26). The exclusion criteria were as follows: contractures limiting range of motion in the lower extremities, lack of ambulation prior to stroke, severe cardiac disease, uncontrolled hypertension despite use of medication (average systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or average diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg measured over 7 days), presence of non-healing ulcers in the lower limbs, and osteoporosis. The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Korea National Rehabilitation Center (IRB no. NRC-2015-01-002).

Participants were randomly allocated to either group A or B using the NCSS-PASS program-generated randomization table, at an allocation ratio of 1:1. A principal investigator generated the random allocation sequence, a researcher enrolled participants, another researcher assigned participants to interventions, and a third-party blinded researcher assessed outcome measures. The randomization assignments were concealed in consecutively numbered, sealed opaque envelopes. The envelopes were opened sequentially after each patient provided written informed consent. Patients in group A underwent an intervention consisting of 4 weeks of RAGT combined with CPT, followed by 4 weeks of CPT. Patients in group B underwent the same interventions in reverse order (i.e., 4 weeks of CPT followed by 4 weeks of RAGT+CPT). The combined RAGT+CPT intervention consisted of 30 min of RAGT and 30 min of CPT (RAGT+CPT), while each intervention during the CPT only period consisted of 60 min of CPT (CPT+CPT). We referred to the former and latter as RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT, respectively. Each intervention consisted of 20 sessions (five sessions each week). All participants were controlled for other gait-related treatments except RAGT and CPT provided in this study.

The Lokomat® robotic-orthosis (Hocoma AG, Zurich, Switzerland) system was used during RAGT. Participants were fitted with a harness so that a portion of their body weight could be supported when walking in the device. Typical initial body-weight support was provided at 70–80%. A minimum of 50% body-weight support was provided to allow participants to focus on the timing of their gait patterns. Typical initial walking speeds were approximately 1.0 km/h. Training difficulty was progressively increased by altering the walking speed and level of body-weight support. For each level of weight support, the speed of the robot-assisted gait was increased in increments of 0.2 km/h per session, up to 3.0 km/h. When the participant could ambulate at a certain level of body-weight support at the highest speed, the level of weight support was reduced by 5–10% per session to a lower limit of 50% (from 70 to 80%). The guidance force provided by the Lokomat was gradually reduced from 100 to 20%. The level of body-weight support and guidance force reduced simultaneously with patient compliance. The participants were requested to “walk with the robot.”

The primary goal of the CPT intervention was to facilitate improvements in static and dynamic balance. CPT consisted of balance-specific activities such as postural stability training, symmetric weight-bearing, general gait training, and trunk control. The structure of the intervention was customized to the functional capacity of each patient. All interventions were performed by skilled and experienced physical therapists. Two physical therapists kept training records that allowed comparison of similarity between therapists to minimize difference. After each intervention, therapists discussed and minimized the differences among the therapists on a daily basis. Each therapist worked with individuals in groups A and B.

Outcome measures were evaluated for each participant at baseline, after 20 intervention sessions (4 weeks), and after 20 sessions of the alternative intervention (8 weeks) by a blinded research therapist. Berg Balance Scale (BBS) scores, which are used to assess balance based on performance during 14 tasks representing common functional movements in daily life, were regarded as the primary outcome measure [26]. Each task is rated on a five-point scale (0–4), with the maximum score of 56 indicating that balance function is within the normal range. The BBS is a representative method for evaluating the balance ability of stroke patients [27]. The BBS measures both static and dynamic aspects of balance and has been demonstrated as good valid, good reliable, and fair to good responsiveness for use in patients with stroke [28–30].

Secondary outcome measures were as follows: (1) Static standing balance as measured using a force plate: Changes in center-of-pressure (COP) were measured to observe more detailed changes in static balance than those that could be captured using BBS scores. For tests of static standing balance, participants were instructed to stand on the force plate and focus on a centrally located spot in front of them, with arms hanging loosely by their sides. Each participant performed the following four tasks resembling those included in the Romberg test: standing with their feet positioned at shoulder-width under eyes-open (FSEO) or eyes-closed (FSEC) conditions, standing with their feet together with eyes-open (FTEO) or eyes-closed (FTEC). Each task was performed for 20 s and repeated three times. A 464 × 508-mm force plate (AMTI Force Platforms, Watertown, MA) was used to obtain a two-dimensional analysis of COP displacements along both the anteroposterior and mediolateral axes of the platform. The force plate was used to record the mean velocity of the COP displacement (mm/s) in the anteroposterior (COP VelAP) and mediolateral (COP VelML) directions, as well as the area of the 90% confidence ellipse enclosing the COP (COP area in mm2). Data were processed and analyzed using Visual 3D™ software (C-Motion, Inc., Rockville, MD). (2) Trunk impairment scale (TIS) scores: The TIS was assessed because trunk control was related to standing balance [31]. The TIS was used to evaluate static sitting balance, dynamic sitting balance, trunk control, and coordination [32]. Scores range from 0 to 23 points, with higher scores indicating better sitting balance or trunk performance. Measures of trunk performance including the TIS have been significantly associated with measures of gait ability [33]. (3) Lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA-LE) scores: The FMA-LE was assessed because improved balance may also contribute to lower extremity function. The 17-item FMA-LE was used to examine motor function and coordination of the affected lower extremity [34]. Total scores on the FMA-LE range from 0 to 34 points, with higher scores indicative of lower levels of impairment. Participants with quadriplegia were evaluated for the more affected side. (4) Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) scores: The FAC was used to assess gait ability, which was rated along six levels (scores ranging from 0 to 5) based on the amount of physical support required, regardless of whether an assistive device was used [35]. Balance function is a significant predictive factor for gait function [36]. A previous systematic review has indicated that balance and gait may share similar components that can be targeted using a single form of therapy [22]. Because gait is a comprehensive function that encompasses balance, RAGT should influence both gait and balance in this patient population. (5) Results of 10-m walk test (10MWT) at self-selected and fast walking speeds: The 10MWT was used to examine gait speed, and the participant was asked to walk on a 14-m walkway while wearing harness, under two conditions: at the fastest speed or at a self-selected, comfortable speed. Measurements were obtained for the 10-m region in the center of the walkway, while the 2-m acceleration and deceleration areas were excluded [37]. The 10MWT was performed three times, and the average value was used. The participants were using their own walking aid during 10MWT. (6) Falls Efficacy Scale (FES) scores: The FES requires participants to rank their confidence in their ability not to fall while performing various activities of daily living. The maximum score on the FES is 100 points [38]. (7) Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) scores: The SARA was a clinical scale that is based on a quantitative assessment of cerebellar ataxia on an impairment level. Only three items related to balance were used: gait, stance, and sitting. A zero score means no ataxia, and a higher score means a more severe ataxia [39].

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for normality test. The baseline homogeneity of groups A and B in BBS, static standing balance, TIS, FMA-LE, FAC, 10MWT, FES, and SARA was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The potential effects of training order were examined by comparing results between groups A and B. Outcomes were thus compared using 2 (Group; group A, B) × 2 (Time; baseline, 8 weeks) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA).

Further comparisons were made for the effect of RAGT combined with CPT and CPT only on balance function among persons with infratentorial stroke. Differences between RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT were compared using 2 (intervention: RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT) × 2 (time: pre- and post-intervention) repeated-measures ANOVA. Post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare pre- and post-intervention results between the RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT interventions.

The likelihood ratio test was used to test the significance of the carry-over effect for treatment effect (), using the following equation: ∆G2 = (−2 log LReduced) − (−2 log LFull) with dfFull degrees of freedom. Outcome variables displaying no carry-over effects were then compared using 2 (group: groups A, B) × 2 (time: baseline, 8 weeks) repeated-measures ANOVA.

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Nineteen participants with infratentorial stroke (16 men, three women; mean ± standard deviation age: 47.4 ± 11.6 years) were included in this study (Tables 1 and 2). Participants were either in the subacute or chronic phases of post-stroke recovery, and the mean time after stroke was 15.3 ± 25.0 months. Of the 10 participants initially recruited in group A and the nine participants recruited in group B, two dropped out during the 4-week intervention, including one in group A (withdrew consent) and one in group B (withdrew consent). Ultimately, 17 participants (group A, n = 9; group B, n = 8) completed the study and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| No. | Sex | Age (year) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Time since stroke (months) | FMA-LE score at baseline | SARA | Diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait | Stance | Sitting | ||||||||

| Group A | ||||||||||

| 1 | M | 47 | 163 | 63 | 11 | 24 | 4 | 2 | 1 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral pontine infarction |

| 2 | F | 39 | 165 | 70 | 111 | 27 | 4 | 3 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral cerebellar infarction |

| 3 | M | 57 | 177 | 67 | 30 | 22 | 6 | 5 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral pontine and cerebellar infarction |

| 4 | M | 56 | 169 | 75 | 30 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral midbrain and pontine hemorrhage |

| 5 | M | 59 | 160 | 59 | 11 | 16 | 5 | 2 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral pontine infarction |

| 6 | M | 44 | 170 | 71 | 3 | 31 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Left hemiplegia d/t right medullary infarction |

| 7 | M | 40 | 174 | 88 | 5 | 21 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Right hemiplegia d/t left pontine hemorrhage |

| 8 | M | 51 | 168 | 70 | 2 | 28 | 7 | 4 | 0 | Right hemiplegia d/t right cerebellar hemorrhage |

| 9 | M | 49 | 173 | 64 | 2 | 33 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Right hemiplegia d/t right medullary infarction |

| 10a | M | 45 | 170 | 56 | 7 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Right hemiplegia d/t Right cerebellar hemorrhage |

| Group B | ||||||||||

| 11 | M | 37 | 170 | 85 | 15 | 30 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t right pontine and cerebellar hemorrhage |

| 12 | M | 67 | 171 | 77 | 3 | 21 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t left pontine and cerebellar infarction |

| 13a | M | 71 | 166 | 65 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 1 | Quadriplegia d/t right hemiplegia d/t right cerebellar hemorrhage |

| 14 | F | 33 | 165 | 62 | 2 | 28 | 5 | 3 | 0 | Right hemiplegia d/t left medullary infarction |

| 15 | M | 48 | 178 | 74 | 12 | 21 | 6 | 4 | 0 | Right hemiplegia d/t left pontine hemorrhage |

| 16 | M | 49 | 171 | 74 | 4 | 25 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t left pontine and bilateral cerebellar infarction |

| 17 | F | 22 | 163 | 63 | 27 | 29 | 6 | 3 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral cerebellar hemorrhage |

| 18 | M | 39 | 170 | 78 | 3 | 29 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral medullary infarction |

| 19 | M | 48 | 167 | 63 | 8 | 29 | 5 | 4 | 0 | Quadriplegia d/t bilateral cerebellar hemorrhage |

aTwo participants withdrew and were not included in the analyses. FMA-LE lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment, SARA Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia

Table 2.

Group demographics

| Group A | Group B | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 9 (90.0%) | 7 (77.8%) | 0.466 |

| Female | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | ||

| Age (year) | 48.70 ± 7.01 | 46.00 ± 15.64 | 0.497 | |

| Height (cm) | 168.90 ± 5.17 | 169.00 ± 4.42 | 0.968 | |

| Weight (kg) | 68.30 ± 9.02 | 71.22 ± 8.24 | 0.497 | |

| Time since stroke (months) | 21.20 ± 33.27 | 10.22 ± 8.54 | 0.842 | |

| FMA-LE score | 25.50 ± 5.02 | 24.67 ± 6.50 | 0.905 | |

| SARA | Gait | 3.60 ± 1.90 | 4.56 ± 2.13 | 0.356 |

| Stance | 2.50 ± 1.20 | 2.67 ± 1.50 | 0.905 | |

| Sitting | 0.10 ± 0.32 | 0.11 ± 0.33 | 0.968 | |

FMA-LE lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment, SARA Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

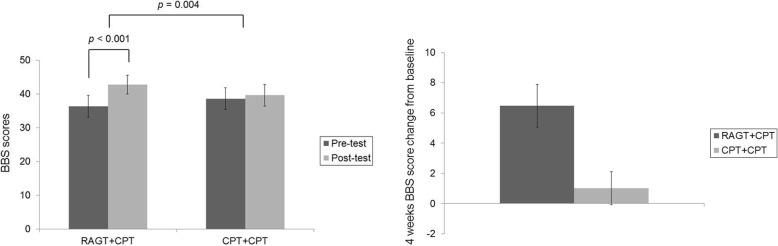

Groups A and B exhibited no significant differences in outcome-related variables at baseline or time-by-group interactions (Table 3, Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2). Therefore, findings were compared between the RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT interventions, rather than between groups A and B. Significantly greater improvements in BBS scores were observed for RAGT+CPT than for CPT+CPT (F = 9.354, df = 1.000, p = 0.004) (Fig. 2). Figure 3 displays the changes in static standing balance throughout the intervention. Significantly greater improvements in COP VelML during FSEC (p = 0.016) and during FTEC (p = 0.018) were observed for RAGT+CPT than for CPT+CPT. In addition, significant improvements were observed in COP VelML during FSEO (p = 0.049), COP VelML during FSEC (p = 0.006), COP VelML during FTEC (p = 0.036), COP VelAP during FSEC (p = 0.049), COP VelAP during FTEC (p = 0.036), and COP area during FSEC (p = 0.015) for RAGT+CPT, but not for CPT+CPT. No significant differences or changes were observed in other variables associated with static standing balance.

Table 3.

Outcome measures pre- and post-intervention in groups A and B

| Group A | Group B | F | P, time effect | P, group-by-time interaction | P, baseline comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8 weeks | Baseline | 8 weeks | ||||||

| BBS | 36.89 ± 14.74 40.00 (27.00–49.00) | 43.11 ± 13.62 48.00 (35.00–53.00) | 33.00 ± 11.99 34.00 (21.00–42.75) | 41.88 ± 9.99 44.50 (31.50–50.75) | 0.444 | 0.002 | 0.515 | 0.423 | |

| FSEO | COP VelML (mm/s) | 11.78 ± 7.78 10.47 (8.04–21.62) | 14.07 ± 8.67 12.60 (7.10–27.70) | 14.69 ± 5.38 14.11 (10.27–18.50) | 9.96 ± 2.56 9.59 (7.74–11.83) | 0.389 | 0.545 | 0.210 | 0.210 |

| COP VelAP (mm/s) | 18.17 ± 11.90 16.27 (12.75–32.74) | 21.17 ± 16.66 20.08 (11.17–53.22) | 25.56 ± 13.29 20.31 (17.38–37.37) | 19.35 ± 10.34 17.78 (10.60–24.02) | 0.931 | 0.793 | 0.175 | 0.175 | |

| COP Area (mm2) | 99.13 ± 26.56102.95 (71.36–125.88) | 105.65 ± 38.55103.11 (66.90–138.71) | 146.28 ± 111.49108.45 (95.65–133.17) | 89.05 ± 19.37 90.18 (69.79–107.19) | 2.074 | 0.104 | 0.442 | 0.442 | |

| FSEC | COP VelML | 12.64 ± 7.21 9.90 (7.00–19.66) | 21.62 ± 30.27 8.28 (7.54–42.37) | 15.09 ± 6.00 14.18 (9.43–21.23) | 11.33 ± 3.37 10.64 (8.56–13.45) | 2.537 | 0.527 | 0.657 | 0.657 |

| COP VelAP | 17.88 ± 5.20 18.30 (13.35–22.19) | 31.29 ± 35.33 14.02 (12.65–58.57) | 30.28 ± 15.61 27.93 (17.86–42.74) | 26.12 ± 10.70 23.31 (16.84–34.60) | 1.798 | 0.494 | 0.600 | 0.600 | |

| COP Area | 124.05 ± 49.10117.75 (92.09–155.72) | 118.82 ± 59.80102.60 (82.21–150.58) | 142.84 ± 78.93134.40 (71.68–218.84) | 112.48 ± 55.39105.98 (81.52–115.11) | 1.337 | 0.262 | 0.574 | 0.574 | |

| FTEO | COP VelML | 39.85 ± 22.22 37.68 (17.42–60.22) | 28.34 ± 13.00 24.82 (17.63–43.52) | 46.24 ± 18.72 43.59 (29.42–64.39) | 37.03 ± 18.07 41.21 (18.18–53.80) | 0.020 | 0.239 | 0.573 | 0.573 |

| COP VelAP | 45.59 ± 27.43 46.26 (19.65–71.78) | 37.46 ± 26.76 28.86 (16.61–63.59) | 44.05 ± 21.02 41.73 (28.07–61.19) | 40.22 ± 23.16 47.37 (16.40–60.47) | 0.028 | 0.650 | 0.755 | 0.755 | |

| COP Area | 173.17 ± 71.37150.60 (114.56–246.49) | 168.70 ± 73.69177.01 (89.24–234.05) | 168.13 ± 77.28132.55 (104.89–249.15) | 131.89 ± 39.47154.40 (89.65–162.88) | 0.926 | 0.446 | 0.876 | 0.876 | |

| FTEC | COP VelML | 46.05 ± 21.08 50.45 (23.12–56.45) | 30.17 ± 22.01 19.84 (15.23–43.75) | 69.20 ± 28.14 78.56 (39.36–89.67) | 62.06 ± 22.64 62.54 (40.13–83.52) | 0.176 | 0.320 | 0.286 | 0.286 |

| COP VelAP | 47.33 ± 29.39 41.97 (20.99–62.94) | 23.18 ± 8.09 19.71 (17.40–19.71) | 62.88 ± 25.69 68.35 (37.23–83.05) | 50.27 ± 13.92 47.81 (38.45–64.55) | 0.265 | 0.162 | 0.413 | 0.413 | |

| COP Area | 284.09 ± 217.10228.70 (112.50–363.87) | 117.79 ± 19.68127.52 (103.87–121.03) | 193.41 ± 67.05224.23 (116.49–246.71) | 134.36 ± 15.12151.82 (125.63–164.56) | 0.648 | 0.175 | 0.786 | 0.786 | |

| TIS | 13.89 ± 4.37 14.00 (11.00–17.50) | 15.44 ± 3.28 16.00 (13.00–18.00) | 13.00 ± 3.16 13.50 (9.50–16.25) | 17.62 ± 1.85 17.50 (16.25–18.75) | 3.935 | 0.001 | 0.066 | 0.606 | |

| FMA-LE | 25.56 ± 5.32 27.00 (21.50–29.50) | 27.11 ± 3.92 28.00 (23.00–30.50) | 26.50 ± 3.70 28.50 (22.00–29.00) | 29.00 ± 3.07 29.00 (26.00–31.25) | 0.422 | 0.014 | 0.526 | 0.673 | |

| FAC | 3.00 ± 1.32 4.00 (1.50–4.00) | 3.56 ± 1.33 4.00 (2.50–4.50) | 2.50 ± 1.20 2.50 (1.25–3.75) | 3.25 ± 0.71 3.00 (3.00–4.00) | 0.205 | 0.008 | 0.657 | 0.423 | |

| 10MWT (m/s) | Self-selected walking speed | 0.49 ± 0.41 0.66 (0.07–0.88) | 0.64 ± 0.42 0.76 (0.23–0.99) | 0.25 ± 0.28 0.19 (0.02–0.49) | 0.37 ± 0.32 0.26 (0.11–0.72) | 0.033 | 0.067 | 0.858 | 0.333 |

| Fast walking speed | 0.68 ± 0.59 0.87 (0.07–1.26) | 0.97 ± 0.67 1.09 (0.26–1.48) | 0.40 ± 0.40 0.22 (0.05–0.78) | 0.51 ± 0.49 0.32 (0.11–1.09) | 0.731 | 0.083 | 0.406 | 0.333 | |

| FES | 59.44 ± 19.66 63.00 (46.50–75.00) | 72.67 ± 25.52 79.00 (55.00–93.00) | 45.88 ± 18.08 44.50 (32.50–59.00) | 58.37 ± 13.36 57.50 (49.00–68.75) | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.937 | 0.139 | |

| SARA | Gait | 3.78 ± 1.92 4.00 (2.00–5.50) | 3.00 ± 1.58 2.00 (2.00–4.00) | 4.13 ± 1.80 5.00 (2.00–5.75) | 3.50 ± 1.78 3.00 (2.00–5.50) | 0.050 | 0.057 | 0.825 | 0.650 |

| Stance | 2.56 ± 1.24 2.00 (2.00–3.50) | 1.89 ± 1.17 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 2.38 ± 1.30 2.50 (1.00–3.75) | 2.00 ± 0.93 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 0.226 | 0.110 | 0.641 | 0.765 | |

| Sitting | 0.11 ± 0.33 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 ± 0.00 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.882 | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.346 | |

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range). BBS Berg Balance Scale, COP center of pressure, FSEO feet separated, eyes open, FSEC feet separated, eyes closed, FTEO feet together, eyes open, FTEC feet together, eyes closed, TIS Trunk Impairment Scale, FMA-LE lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment, FAC Functional Ambulation Category, 10MWT 10-m walking test, FES Falls Efficacy Scale, SARA Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia

Fig. 2.

Left: BBS scores between RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT groups before and after intervention. Right: Four weeks BBS score change from baseline. The error bars means standard errors. BBS: Berg Balance Scale; CPT: conventional physical therapy; RAGT: robot-assisted gait training

Fig. 3.

Left: COP-based variables during FSEO, FSEC, FTEO, and FTEC in the RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT groups. Right: Four weeks COP-based variables change from baseline during FSEO, FSEC, FTEO, and FTEC. (A) COP VelML, (B) COP VelAP, and (C) COP area. The error bars mean standard errors. COP: center of pressure; CPT: conventional physical therapy; FSEC: feet separated, eyes closed; FSEO: feet separated, eyes open; FTEC: feet together, eyes closed; FTEO: feet together, eyes open; RAGT: robot-assisted gait training; VelAP: velocity in the anteroposterior direction; VelML: velocity in the mediolateral direction

Table 4 shows the results for the TIS, FMA-LE, FAC, 10MWT (self-selected walking speed and fast walking speed), FES, and SARA. Significant differences between the RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT conditions were observed for FMA-LE (p = 0.001) scores and SARA gait (p = 0.033) and stance scores (p = 0.002), but not for TIS (p = 0.268), FAC (p = 0.140), FES (p = 0.062), or SARA sitting scores (p = 0.317). RAGT+CPT improved TIS, FMA-LE, FAC, FES, SARA gait, and SARA stance scores, while CPT+CPT improved TIS and SARA gait scores. Neither intervention significantly influenced 10MWT results for self-selected walking speed or fast walking speed.

Table 4.

Secondary outcome measures pre- and post-intervention in the RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT interventions

| RAGT+CPT | CPT+CPT | P, group-by-time interaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | P, within | Pre-test | Post-test | P, within | |||

| TIS | 14.35 ± 3.32 15.00 (12.00–16.50) | 16.18 ± 3.36 17.00 (14.50–18.50) | 0.003 | 14.00 ± 3.62 14.00 (10.50–17.00) | 15.18 ± 2.58 15.00 (14.00–16.50) | 0.040 | 0.268 | |

| FMA-LE | 26.06 ± 4.41 28.00 (22.00–29.00) | 28.41 ± 3.99 29.00 (25.00–32.00) | 0.002 | 27.24 ± 4.24 28.00 (23.00–30.50) | 26.88 ± 3.57 28.00 (23.00–29.50) | 0.477 | 0.001 | |

| FAC | 2.88 ± 1.17 3.00 (2.00–4.00) | 3.41 ± 1.06 4.00 (3.00–4.00) | 0.011 | 3.06 ± 1.35 3.00 (2.00–4.00) | 3.18 ± 1.24 3.00 (2.00–4.00) | 0.157 | 0.140 | |

| 10MWT (m/s) | Self-selected speed | 0.53 ± 0.31 0.62 (0.24–0.82) | 0.61 ± 0.38 0.69 (0.18–0.86) | 0.087 | 0.58 ± 0.39 0.64 (0.19–0.87) | 0.59 ± 0.34 0.60 (0.31–0.80) | 0.433 | 0.603 |

| Fastest speed | 0.71 ± 0.47 0.87 (0.27–1.11) | 0.96 ± 0.55 1.01 (0.45–1.26) | 0.060 | 0.84 ± 0.57 0.81 (0.23–1.22) | 0.85 ± 0.57 0.98 (0.36–1.23) | 0.925 | 0.400 | |

| FES | 56.88 ± 15.55 57.00 (49.50–65.00) | 67.82 ± 21.36 71.00 (50.00–86.50) | 0.018 | 61.94 ± 26.09 63.00 (39.50–86.50) | 63.88 ± 21.41 62.00 (50.00–80.00) | 0.629 | 0.150 | |

| SARA | Gait | 3.76 ± 1.86 4.00 (2.00–5.50) | 3.18 ± 1.63 2.00 (2.00–4.00) | 0.020 | 3.94 ± 1.82 3.00 (2.00–5.00) | 3.29 ± 1.72 2.00 (2.00–5.00) | 0.039 | 0.033 |

| Stance | 2.53 ± 1.18 2.00 (2.00–3.50) | 1.76 ± 0.90 2.00 (1.00–2.50) | 0.006 | 2.47 ± 1.23 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 2.00 ± 1.12 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 0.130 | 0.002 | |

| Sitting | 0.06 ± 0.24 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.06 ± 0.24 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 1.000 | 0.06 ± 0.24 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.06 ± 0.24 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 1.000 | 0.325 | |

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range). 10MWT 10-m walking test, FAC Functional Ambulation Category, FES Falls Efficacy Scale, FMA-LE lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment, CPT conventional physical therapy, RAGT robot-assisted gait training, SARA Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia, TIS Trunk Impairment Scale

Significant carry-over effects were observed for all variables except FAC (G2 = 0.4) and SARA stance scores (G2 = 1.8). FAC (F = 12.775; p = 0.003), and SARA stance (F = 11.029; p = 0.005) scores exhibited significant group-by-time interactions, indicating that RAGT+CPT followed by CPT+CPT was superior with regard to independent walking and stance posture of ataxia.

Discussion

This study is the first clinical trial to demonstrate the effect of RAGT on balance and lower extremity function among patients with infratentorial stroke. Our results indicated that RAGT+CPT resulted in significantly greater improvements in standing balance function than the same duration of CPT+CPT. In addition, improvements in balance confidence were observed following RAGT+CPT, but not following CPT+CPT.

Notably, BBS scores for the RAGT+CPT intervention increased by 6.5 points, exceeding the minimal detectable change of 6 points [40]. To our knowledge, only two studies have reported that RAGT is superior to CPT; however, they failed to achieve clinically meaningful changes in BBS scores [24, 40]. The subjects of Bang and Shin’s [24] study were patients who were already able to walk independently, so there might be a limit to the degree of improvement of balance ability. The treatment group of Yoshimoto et al. [41] underwent robot-assisted gait intervention once a week for 8 weeks (20 min/session), for a total of eight sessions, which may not be sufficient to achieve adequate improvement in balance. Conversely, in our study, RAGT facilitated clinically meaningful changes in balance function among individuals with infratentorial stroke. These results led to the improvement of SARA gait and stance scores in the RAGT+CPT group. This appears to be due to the SARA gait and stance evaluation reflects ataxia properties such as dysmetria and dysdiadochokinesia in individuals with infratentorial stroke.

When compared with CPT+CPT, the FMA-LE score significantly improved by only 2.35 points for RAGT+CPT. This improvement is below the most frequently used minimal clinically significant difference of 6 points recently suggested by Pandian et al. [42]. Similarly, the TIS score improved significantly but subclinically for both groups. Further studies involving larger numbers of patients are therefore required.

The observed effects of RAGT on balance can be explained by several possible mechanisms. First, RAGT may lead to somatosensory facilitation including proprioceptive systems, which should be emphasized among individuals with infratentorial stroke. Such enhancements would be marked in the eyes-closed condition, as patients with infratentorial stroke, who commonly exhibit vestibular or oculomotor dysfunction, may rely heavily on vision for maintaining balance. In our study, a significant difference between RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT was observed for the eyes-closed condition only.

Second, RAGT enables loading and weight-shifting to the affected side, allowing for latero-lateral weight-shifting, resulting in symmetrical gait patterns [43, 44]. Because in quadriplegia weight is mainly supported by the less affected side, it is effective even if it is not hemiplegia. Similarly, RAGT+CPT exerted greater effects on COP VelML than CPT+CPT, and the most prominent change due to RAGT+CPT was also observed for COP VelML. Thus, RAGT may allow for greater improvements in control over COP VelML, thereby decreasing the risk of falls [45].

Third, RAGT may have altered muscle activity in the lower extremities leading to improvements in functional performance. Partial weight-bearing gait training resulted in reduction in the mean burst amplitude of muscles for gastrocnemius and increase in mean burst amplitude of tibialis anterior [46]. These pattern changes resulted in better stability against common activation pattern in stroke patients, that is, higher activation of gastrocnemius and reduced activation of tibialis anterior. RAGT changed muscle coordination pattern with the controlling amount of weight support and stride frequency [47]. Moreover, the RAGT improved the motoneuronal firing rate by increasing motor unit firing without altering muscle force [48]. These muscle activity alterations without muscle force change may have led to an improvement in balance in patients with stroke who have difficulty in improving muscle strength.

In the present study, RAGT+CPT was more likely to result in better lower extremity function than CPT+CPT, as demonstrated by more significant improvement in FMA-LE scores. Within-group significant change was observed in FAC score of the RAGT+CPT group; however, no between-group difference was noted. Previous studies have reported that RAGT or treadmill-supported gait training resulted in greater improvements in lower extremity function compared with conventional gait training [22, 49, 50]. In addition, one systematic review reported that gait training may increase the risk of falls in older adults, while balance training may reduce this risk [51]. Indeed, RAGT may safely facilitate improvements in overall lower extremity function including balance.

However, no significant differences in sitting balance or trunk coordination as indicated by TIS scores were observed between RAGT+CPT and CPT+CPT. This finding suggests task-specific effects of RAGT on balance and biomechanically similar movements, in accordance with the findings of previous studies [52–54]. Our RAGT protocol may have been unable to recruit trunk stabilizers or improve trunk-related proprioception, as the trunk was equipped with a harness when the exoskeleton made large movements of the lower extremity.

On the contrary, most variables exhibited carry-over effects, except for FAC and SARA stance, for which we observed significant group-by-time interactions. Thus, RAGT+CPT followed by CPT+CPT was more effective with regard to independent walking and stance posture compared to intervention conducted in the reverse order. Previous researchers have proposed that proximal trunk control training prior to distal mobility training is essential for proper weight shifting and distal limb control [32]. Thus, prior RAGT may be optimal for improving independent gait and standing balance.

This study has some limitations. First, various evaluations related to balance, such as MiniBESTest or dynamic gait index, was not performed. In addition, we did not measure kinetic or electromyography data, which may be useful for determining the mechanisms underlying the effects of RAGT. This may result in insufficient understanding of the mechanism of RAGT. Second, in this study, the duration and intensity of RAGT could be too low to promote meaningful recovery, and the long-term effects of follow-up were not assessed. This did not confirm the underlying neuroplasticity based on impairment level. Third, the sample size was small, and this clinical trial was performed using a crossover design without a washout period. Moreover, the standard deviation of the static standing balance measure is large because of the gap between each subject’s balance ability, as this is a sensitive assessment. This might cause a type II statistical error. Therefore, there is a limit to the generalization of this result, and attention should be paid to statistical analysis.

Conclusions

RAGT produced clinically significant improvements in static and dynamic balance and FMA-LE function in patients with infratentorial stroke. RAGT+CPT resulted in significantly greater improvements in standing balance and lower extremity motor function than the same duration of CPT. These findings indicate that RAGT may be useful for patients with balance impairments secondary to other pathologies, as infratentorial stroke shares many balance-related components.

Additional files

COP-based variables during FSEO, FSEC, FTEO, and FTEC from baseline to 8weeks in the groups A and B. (A) COP VelML, (B) COP VelAP, and (C) COP area. The error bars means standard errors. COP: center of pressure; FSEC: feet separated, eyes closed; FSEO: feet separated, eyes open; FTEC: feet together, eyes closed; FTEO: feet together, eyes open; VelAP: velocity in the anteroposterior direction; VelML: velocity in the mediolateral direction. (JPG 143 kb)

Secondary outcome measures from baseline to 8weeks in the groups A and B. (A) TIS, (B) FMA-LE, (C) FAC, and (D) FES. The error bars means standard errors. FAC: Functional Ambulation Category; FES: Falls Efficacy Scale; FMA-LE: lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment; TIS: Trunk Impairment Scale. (JPG 60 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Abbreviations

- 10MWT

10-m walk test

- ANOVA

Analyses of variance

- BBS

Berg Balance Scale

- COP

Center of pressure

- CPT

Conventional physical therapy

- FAC

Functional Ambulation Category

- FES

Falls Efficacy Scale

- FMA-LE

Lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment

- FSEC

Feet separated, eyes closed

- FSEO

Feet separated, eyes open

- FTEC

Feet together, eyes closed

- FTEO

Feet together, eyes open

- RAGT

Robot-assisted gait training

- SARA

Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia

- TIS

Trunk Impairment Scale

- VelAP

Velocity in the anteroposterior direction

- VelML

Velocity in the mediolateral direction

Authors’ contributions

HYK carried out the clinical trial sessions, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JS conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. SPY carried out the clinical trial sessions. MAS helped revise the manuscript. SHL helped revise the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant (NRCTR-IN15002, NRCTR-IN16002) from the Translational Research Center for Rehabilitation Robots, Korea National Rehabilitation Center, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Korea.

Availability of data and materials

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Korea National Rehabilitation Center Institutional Review Board (NRC-2015-01-002).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Harris JE, Eng JJ, Marigold DS, Tokuno CD, Louis CS. Relationship of balance and mobility to fall incidence in people with chronic stroke. Phys Ther. 2005;85:150–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery. Stroke. 2016;47:e98–e169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diringer MN. Intracerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology and management. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1591–1603. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199310000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Bos GA, Smits JP, Westert GP, van Straten A. Socioeconomic variations in the course of stroke: unequal health outcomes, equal care? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:943–948. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.12.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emsley HC. Posterior circulation stroke: still a Cinderella disease. BMJ. 2013;346:f3552. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmahmann JD. Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:367–378. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121:561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton SM, Bastian AJ. Cerebellar control of balance and locomotion. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:247–259. doi: 10.1177/1073858404263517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thach WT, Bastian AJ. Role of the cerebellum in the control and adaptation of gait in health and disease. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:353–366. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prosperini L, Kouleridou A, Petsas N, Leonardi L, Tona F, Pantano P, et al. The relationship between infratentorial lesions, balance deficit and accidental falls in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;304:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sale P, Franceschini M, Waldner A, Hesse S. Use of the robot assisted gait therapy in rehabilitation of patients with stroke and spinal cord injury. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48:111–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:S225–S239. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrholz J, Thomas S, Werner C, Kugler J, Pohl M, Elsner B. Electromechanical-assisted training for walking after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD006185. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006185.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong RK, Ng MF, Li LS. Effectiveness of gait training using an electromechanical gait trainer, with and without functional electric stimulation, in subacute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2006;87:1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayr A, Kofler M, Quirbach E, Matzak H, Fröhlich K, Saltuari L. Prospective, blinded, randomized crossover study of gait rehabilitation in stroke patients using the Lokomat gait orthosis. Neurorehab Neural Repair. 2007;21:307–314. doi: 10.1177/1545968307300697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pohl M, Werner C, Holzgraefe M, Kroczek G, Wingendorf I, Hoölig G, et al. Repetitive locomotor training and physiotherapy improve walking and basic activities of daily living after stroke: a single-blind, randomized multicentre trial (DEutsche GAngtrainerStudie, DEGAS) Clinical Rehab. 2007;21:17–27. doi: 10.1177/0269215506071281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornby TG, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, Demott T, Moore JL, Roth HR. Enhanced gait-related improvements after therapist-versus robotic-assisted locomotor training in subjects with chronic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1786–1792. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.504779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hidler J, Nichols D, Pelliccio M, Brady K, Campbell DD, Kahn JH, et al. Multicenter randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Lokomat in subacute stroke. Neurorehab Neural Repair. 2009;23:5–13. doi: 10.1177/1545968308326632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peurala SH, Airaksinen O, Huuskonen P, Jäkälä P, Juhakoski M, Sandell K, et al. Effects of intensive therapy using gait trainer or floor walking exercises early after stroke. J Rehab Med. 2009;41:166–173. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesse S, Bardeleben A, Werner C, Waldner A. Robot-assisted practice of gait and stair climbing in nonambulatory stroke patients. J Rehab Res Devel. 2012;49:613. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2011.08.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taveggia G, Borboni A, Mulé C, Villafañe JH, Negrini S. Conflicting results of robot-assisted versus usual gait training during postacute rehabilitation of stroke patients: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Rehab Res. 2016;39:29–35. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swinnen E, Beckwée D, Meeusen R, Baeyens JP, Kerckhofs E. Does robot-assisted gait rehabilitation improve balance in stroke patients? A systematic review. Topics Stroke Rehab. 2014;21:87–100. doi: 10.1310/tsr2102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SY, Yang L, Park IJ, Kim EJ, Park MS, You SH, et al. Effects of innovative WALKBOT robotic-assisted locomotor training on balance and gait recovery in hemiparetic stroke: a prospective, randomized, experimenter blinded case control study with a four-week follow-up. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehab Eng. 2015;23:636–642. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2015.2404936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang DH, Shin WS. Effects of robot-assisted gait training on spatiotemporal gait parameters and balance in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurorehabilitation. 2016;38:343–349. doi: 10.3233/NRE-161325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cifu DX. Braddom’s physical medicine & rehabilitation, fifth ed. chapter 44 stroke syndromes. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 999–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg KO, Wood-Duaphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83(Suppl 2):S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Oliveira CB, de Medeiros IR, Frota NA, Greters ME, Conforto AB. Balance control in hemiparetic stroke patients: main tools for evaluation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45:1215–1226. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2007.09.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blum L, Korner-Bitensky N. Usefulness of the Berg balance scale in stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2008;88:559–566. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liston RA, Brouwer BJ. Reliability and validity of measures obtained from stroke patients using the balance master. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:425–430. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(96)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao HF, Hsueh IP, Tang PF, Sheu CF, Hsieh CL. Analysis and comparison of the psychometric properties of three balance measures for stroke patients. Stroke. 2002;33:1022–1027. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000012516.63191.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Criekinge Tamaya, Truijen Steven, Schröder Jonas, Maebe Zoë, Blanckaert Kyra, van der Waal Charlotte, Vink Marijke, Saeys Wim. The effectiveness of trunk training on trunk control, sitting and standing balance and mobility post-stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2019;33(6):992–1002. doi: 10.1177/0269215519830159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verheyden G, Nieuwboer A, Mertin J, Preger R, Kiekens C, de Weerdt W. The trunk impairment scale: a new tool to measure motor impairment of the trunk after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:326–334. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr733oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verheyden G, Vereeck L, Truijen S, Troch M, Herregodts I, Lafosse C, et al. Trunk performance after stroke and the relationship with balance, gait and functional ability. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:451–458. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr955oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Stegline S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. A method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7:13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehrholz J, Wagner K, Rutte K, Meissner D, Pohl M. Predictive validity and responsiveness of the functional ambulation category in hemiparetic patients after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1314–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.06.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Hwang SW, Pyo H, Yang SP, Lim MH, et al. Clinical characteristics of proper robot-assisted gait training group in non-ambulatory subacute stroke patients. Ann Rehab Med. 2016;40:183–189. doi: 10.5535/arm.2016.40.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng SS, Ng PC, Lee CY, Ng ES, Tong MH. Walkway lengths for measuring walking speed in stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:43–46. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990;45:239–243. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.P239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitz-Hubsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C, Giunti P, Globas C, Infante J, Kang JS, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66:1717–1720. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219042.60538.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevenson TJ. Detecting change in patients with stroke using the Berg balance scale. Aus J Physiother. 2001;47:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshimoto T, Shimizu I, Hiroi Y, Kawaki M, Sato D, Nagasawa M. Feasibility and efficacy of high-speed gait training with a voluntary driven exoskeleton robot for gait and balance dysfunction in patients with chronic stroke: nonrandomized pilot study with concurrent control. Int J Rehab Res. 2015;38:338–343. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pandian S, Arya KN, Kumar D. Minimal clinically important difference of the lower-extremity Fugl-Meyer assessment in chronic-stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2016;68:233–239. doi: 10.1179/1945511915Y.0000000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banala SK, Kim SH, Agrawal SK, Scholz JP. Robot assisted gait training with active leg exoskeleton (ALEX) IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehab Eng. 2009;17:2–8. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2008.2008280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinovitch SN, Feldman F, Yang Y, Schonnop R, Leung PM, Sarraf J, et al. Video capture of the circumstances of falls in elderly people residing in long-term care: an observational study. Lancet. 2013;381:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61263-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pizzigalli L, Miceheletti Cremasco M, Mulasso A, Rainoldi A. The contribution of postural balance analysis in older adult fallers: a narrative review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finch L, Barbeau H, Arsenault Influence of body weight support on normal human gait: development of a gait retraining strategy. Phys Ther. 1991;71:842–855. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.11.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klarner T, Chan HK, Wakeling JM, andLam T. Patterns of muscle coordination vary with stride frequency during weight assisted treadmill walking. Gait Posture. 2010;31:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chisari C, Bertolucci F, Monaco V, Venturi M, Simonella C, Micera S, et al. Robot-assisted gait training improves motor performances and modifies motor unit firing in poststroke patients. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mudge S, Rochester L, Recordon A. The effect of treadmill training on gait, balance and trunk control in a hemiplegic subject: a single system design. Disability Rehab. 2003;25:1000–1007. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000122320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Combs SA, Dugan EL, Passmore M, Riesner C, Whipker D, Yingling E, et al. Balance, balance confidence, and health-related quality of life in persons with chronic stroke after body weight–supported treadmill training. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2010;91:1914–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Close JC. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatric Society. 2008;56:2234–2243. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winstein CJ, Gardner ER, McNeal DR, Barto PS, Nicholson D. Standing balance training: effect on balance and locomotion in hemiparetic adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70:755–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dean CM, Shepherd RB. Task-related training improves performance of seated reaching tasks after stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:722–728. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bultmann U, Pierscianek D, Gizewski ER, Schoch B, Fritsche N, Timmann D, et al. Functional recovery and rehabilitation of postural impairment and gait ataxia in patients with acute cerebellar stroke. Gait Posture. 2014;39:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

COP-based variables during FSEO, FSEC, FTEO, and FTEC from baseline to 8weeks in the groups A and B. (A) COP VelML, (B) COP VelAP, and (C) COP area. The error bars means standard errors. COP: center of pressure; FSEC: feet separated, eyes closed; FSEO: feet separated, eyes open; FTEC: feet together, eyes closed; FTEO: feet together, eyes open; VelAP: velocity in the anteroposterior direction; VelML: velocity in the mediolateral direction. (JPG 143 kb)

Secondary outcome measures from baseline to 8weeks in the groups A and B. (A) TIS, (B) FMA-LE, (C) FAC, and (D) FES. The error bars means standard errors. FAC: Functional Ambulation Category; FES: Falls Efficacy Scale; FMA-LE: lower extremity Fugl-Meyer Assessment; TIS: Trunk Impairment Scale. (JPG 60 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.