Abstract

Purpose of Review

Moderate hypertriglyceridemia is exceedingly common in diabetes, and there is growing evidence that it contributes to residual cardiovascular risk in statin-optimized patients. Major fibrate trials yielded inconclusive results regarding the cardiovascular benefit of lowering triglycerides, although there was a signal for improvement among patients with high triglycerides and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL)—the “diabetic dyslipidemia” phenotype. Until recently, no trials have examined a priori the impact of triglyceride lowering in patients with diabetic dyslipidemia, who are likely among the highest cardiovascular-risk patients.

Recent Findings

In the recent REDUCE IT trial, omega-3 fatty acid icosapent ethyl demonstrated efficacy in lowering cardio-vascular events in patients with high triglycerides, low HDL, and statin-optimized low-density lipoprotein (LDL). The ongoing PROMINENT trial is examining the impact of pemafibrate in a similar patient population.

Summary

Emerging evidence suggests that lowering triglycerides may reduce residual cardiovascular risk, especially in high-risk patients with diabetic dyslipidemia.

Keywords: Hypertriglyceridemia, Type 2 diabetes, Diabetic dyslipidemia, Medications

Introduction

Compared to patients without diabetes, individuals with diabetes are at 2–4 times the risk of stroke and death from heart disease [1]. Elevated triglyceride levels are common in patients with type 2 diabetes. Discussions regarding the cardio-vascular risk associated with moderate hypertriglyceridemia are escalating. While low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is a well-established risk factor in diabetes, and statins remain first-line therapy for cardiovascular risk reduction, it has become apparent that “residual risk” exists for cardiovascular disease, despite attainment of at-goal LDL-C levels [2••].

In the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial, on-statin triglycerides of ≥ 150 mg/dL were independently associated with increased risk of recurrent coronary heart disease [3]. However, in 2010, ACCORD Lipid demonstrated no significant cardiovascular benefit with the use of fenofibrate to target triglycerides in statin-treated patients [4]. While major fibrate trials have yielded conflicting results regarding the cardiovascular benefit of lowering triglycerides [4–10], a systematic review and meta-analysis of these trials suggests benefit in patients with a pattern of high triglycerides and low high-density lipopro-tein (HDL) [11]—a classic lipid phenotype in diabetes referred to as “diabetic dyslipidemia” or “atherogenic dyslipidemia.” In addition to clinical and epidemiologic studies [12–14], genetic [15–19] and Mendelian randomization studies [20–22] have more recently highlighted triglycerides as a modifiable risk factor in cardiovascular disease. Therefore, there is renewed interest in targeting triglycerides to reduce “residual” cardiovascular risk, particularly in patients with diabetes who exhibit a high-risk lipid phenotype and are at baseline heightened risk of cardiovascular events. Here, we review moderate hypertriglyceridemia in diabetes, including a proposed approach to management based on updated evidence.

Triglyceride Metabolism and Diabetic Dyslipidemia

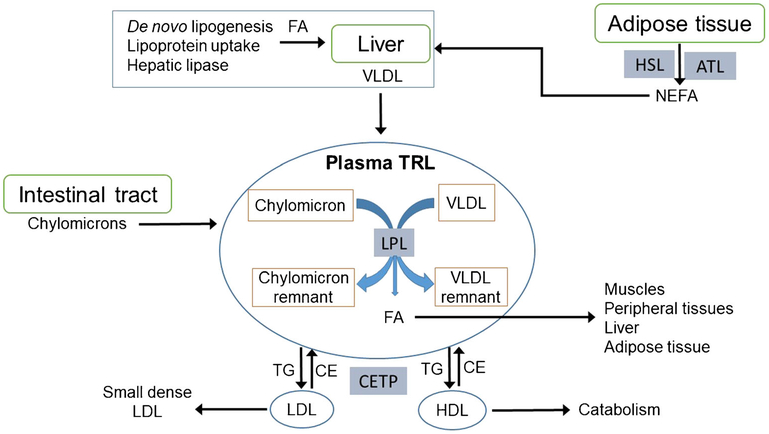

Fatty acids and glucose both have major roles in supplying energy to body tissues during cycles of feeding and fasting. In addition to energy storage within adipocytes and other cells, triglycerides provide bulk transport of esterified fatty acids in circulating chylomicrons, very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), and their remnants. Collectively, these are called triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL). See Fig. 1 for a schematic of TRL metabolism, specifically how plasma TRL interact with organ systems and other lipoprotein particles.

Fig. 1.

Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism. TRL, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; FA, fatty acids; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; TG, triglycerides; CE, cholesterol esters; CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; HSL, hormone sensitive lipase; ATL, adipocyte triglyceride lipase

Fatty acids from the diet are largely incorporated into triglycerides in intestinal mucosal cells and secreted in chylomicrons, which bypass the liver and enter the systemic circulation via intestinal lymph through the thoracic duct.

Chylomicrons then deliver dietary fatty acids to peripheral tissues through the action of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which hydrolyzes chylomicron triglyceride to release free fatty acids, generating chylomicron remnants in the process.

The liver receives some fatty acids from additional lipolysis and uptake of remnant lipoproteins. Other important sources of hepatic fatty acids are (1) de novo hepatic lipogenesis and (2) uptake of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) which circulate in plasma bound to albumin. NEFA are released by adipocytes through the action of hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) and adipocyte triglyceride lipase. Access of these intracellular enzymes to adipocyte triglyceride is suppressed by insulin and activated when insulin levels are very low [23]. Excessive release of NEFA by adipocytes under conditions of insulin resistance and/or deficiency appears to be a major driver of dyslipidemia in diabetes, as well as in insulin-resistant states such as obesity [24].

Circulating VLDL undergo progressive lipolysis by LPL in peripheral tissues, delivering fatty acids for energy use by muscle and other tissues, and for energy storage as triglyceride in adipocytes. LPL activity also produces VLDL remnant particles, called intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL). IDL return to the liver, where they are partly internalized and partly processed at the cell surface by hepatic lipase to become LDL. Insulin also stimulates the function of LPL, so insulin resistance contributes suboptimal metabolism of VLDL particles.

Hypertriglyceridemic states can arise from excess VLDL production and/or inefficient lipolysis. In either case, TRL participate in heteroexchange of neutral lipids (triglycerides and cholesteryl esters) with LDL and HDL via cholesteryl ester transfer protein, which in turn leads to triglyceride en-richment of LDL and HDL particles. Through subsequent action of hepatic lipase, LDL particles become small, dense, and more atherogenic. With similar lipolysis, HDL particles lose some of their apolipoproteins which desorb from the shrinking HDL surface and undergo catabolism in the kidney. Overall, this leads to the classic triad of elevated triglyceride, low HDL, and small dense LDL that characterizes the dyslip-idemia associated with diabetes and insulin resistance [24], known as diabetic dyslipidemia.

Secondary Causes of Hypertriglyceridemia

Prior to starting pharmacotherapy, it is important to consider and address secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia. While not an exhaustive list, Table 1 includes several secondary, nongenetic causes of hypertriglyceridemia. Efforts should be made to optimize lifestyle habits and medical conditions as a means of lowering triglycerides, and if possible, culprit medications should be discontinued.

Table 1.

Secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia

| Lifestyle |

| High glycemic index diet |

| High fructose or sucrose intake |

| Physical inactivity |

| Excess alcohol intake |

| Tobacco abuse |

| Medical conditions |

| Type 2 diabetes |

| Obesity or overweight status |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Nephrotic syndrome |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Cushing’s syndrome |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) |

| Lipodystrophy |

| Acromegaly |

| Pregnancy |

| Medications |

| Oral estrogens |

| Steroids |

| Tamoxifen |

| Atypical antipsychotics |

| Antiretroviral therapy |

| Bile acid sequestrants |

| Thiazides |

| Beta-blockers |

| Cyclosporine |

| Sirolimus |

| Retinoic acid derivatives |

Diabetes is a common and important contributor to dyslipidemia. Poorly controlled diabetes can represent a medical emergency requiring urgent insulin therapy when it leads to extreme hypertriglyceridemia and risk of pancreatitis. However, when one moves from modest to tight glycemic control, say, from hemoglobin A1c of 8.5 to 6.5%, the dyslipidemic triad tends to persist. Dietary measures such as elimination of sugar-sweetened or naturally sweet beverages should be a priority in any patient with hypertriglyceridemia.

Glucose-Lowering Medications and Triglycerides

Glucose-lowering medications have varying effects on tri-glycerides. As mentioned above, insulin lowers circulating triglycerides by a number of mechanisms, including induction of LPL and suppression of HSL. Metformin is a modest insulin sensitizer that can lower triglycerides, an effect that appears independent of its effects on weight and glycemic control [25, 26•, 27, 28•, 29]. A systematic review of 37 studies revealed a decrease in serum triglycerides averaging 11.5 mg/dL with metformin use, although higher doses (> 1700 mg per day) are required to achieve this [25].

Pioglitazone is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-ϒ (PPAR-ϒ) agonist; a strong insulin sensitizer with potent effect on triglycerides. Pioglitazone can reduce triglycerides by up to 50 mg/dL and raise HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) by 5 mg/dL [26•, 27, 28•, 29], although LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) also rises. However, it is important to note that a rise in LDL-C does not necessarily impart higher cardiovascular risk. In fact, LDL particle number (LDL-P) better captures the exceptional atherogenicity of small, dense LDL particles which carry less cholesterol than large, buoyant LDL [30, 31]. Pioglitazone reduces dense atherogenic LDL particles [32]; therefore, it is plausible that this observed rise in LDL-C reflects an increase in LDL particle size rather than particle number (LDL-P). Unlike pioglitazone, rosiglitazone is a PPAR-ϒ agonist with less favorable impact on lipids, as some studies report a neutral effect, while others note increase in triglycerides [26•, 27, 28•, 29].

Sulfonylureas, which act by augmenting beta cell insulin release, have not demonstrated a consistent effect on lipids [29, 33].

Newer glucose-lowering agents have demonstrated benefit in their ability to improve triglycerides. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists improve both fasting and postprandial hypertriglyceridemia with a mean reduction up to 27 mg/dL, but with no consistent effect on HDL levels [26•, 28•, 34, 35••, 36]. Unlike GLP-1 receptor agonists which provide supraphysiological levels of circulating GLP-1, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors increase endogenous GLP-1 levels. Thus, DPP-4 inhibitors generally exert a more modest effect on triglycerides [26•, 29], although mean triglyceride reductions as high as 26 mg/dL have been reported [28•]. For unclear reasons saxagliptin is an exception to the typical DPP-4 inhibitor effect, as it consistently appears lipid-neutral [26•, 29]. Aside from weight loss (GLP-1 receptor agonists only) and glycemic control, incretin-based therapies may lower triglycerides by promoting GLP-1-mediated delay in gastric emptying, reduction of intestinal triglyceride absorption, and subsequent decrease in chylomicron synthesis [37]. Additional mechanisms likely mediate the effects of GLP-1 on lipid metabolism, though they have yet to be fully elucidated.

Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors increase HDL and lead to a 10% reduction in triglycerides, but also raise LDL-C [26•, 28•]. Despite the concern of increasing LDL-C, SGLT2 inhibitors have cardioprotective effects in type 2 diabetes [38•], and similar to pioglitazone, they reduce small, dense LDL particles with a consequent shift towards large, buoyant, less atherogenic LDL [39•].

Established Methods of Lowering Triglycerides

Diet and Lifestyle

Lifestyle modification remains the mainstay of therapy for hypertriglyceridemia. Combining dietary regulation, exercise, and moderation of alcohol intake can reduce triglycerides by up to 60% [40]. In addition, weight loss of 5–10% of initial body weight reduces triglycerides by 25% and increases HDL-C by 8% [40]. A number of dietary approaches may be effective in reducing triglycerides; however, a key theme is avoidance of high glycemic index foods, which is equally important from a diabetes standpoint. A very low fat diet becomes important only when LPL activity is severely impaired, such as in patients with familial chylomicronemia syndrome, or simply when triglycerides are very elevated (e.g., > 1000 mg/dL). When LPL is severely deficient or functionally impaired, there can be rapid accumulation of TRL with contribution of dietary fat [41•], hence the rationale for reducing fat intake. However, for patients with functioning LPL and less than severe hypertriglyceridemia (< 1000 mg/dL), weight loss and low glycemic diet are more effective at lowering triglycerides than low fat diet [42], via reductions of circulating NEFA and of de novo hepatic lipogenesis [43].

Statins

Statins are the cornerstone of treatment for LDL and cardiovascular risk reduction in diabetes. Patients with baseline hypertriglyceridemia experience a 22–45% reduction in levels with statin therapy [44]; however, hypertriglyceridemia may persist. Other available medication classes for the management of hypertriglyceridemia include fibrates, niacin, and omega-3 fatty acids.

Fibrates

Fibrates are often considered first-line adjuncts to manage hypertriglyceridemia if lifestyle modifications and statin therapy fail to achieve goals. Fibrates work by activating PPAR-a, which in turn enhances expression of LPL and other lipid-modifying genes [45]. Currently there are two fibrates approved in the USA: fenofibrate and gemfibrozil. Fibrates are potent triglyceride-lowering agents, reducing plasma levels by 30–50% [46]. Fibrates are generally well tolerated, although risk of muscle toxicity increases when combined with statin therapy. One should avoid gemfibrozil in statin-treated patients for this reason, but fenofibrate can be used safely with some caution [47].

There are mixed data concerning fibrates and cardiovascular outcomes. In the Helsinki Heart Study, gemfibrozil reduced the rate of incident coronary heart disease by 32% [5]. Similarly, VA HIT (Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group) found that gemfibrozil reduced the combined outcome of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and stroke by 24% compared to placebo [8]. Subsequently, the FIELD (Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes) study specifically examined patients with type 2 diabetes (of which there was poor representation in previous studies) and failed to demonstrate a decrease in their composite cardiovascular outcome, although fewer nonfatal myocardial infarctions and revascularizations occurred in the fenofibrate-treated group [6]. High statin initiation in the placebo arm and drop outs in the intervention arm render FIELD a difficult study to interpret, as benefits of fenofibrate may have been masked by these occurrences. ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) Lipid was the first study to examine the cardiovascular benefit of fibrates as add-on therapy to statins [4]. This study did not demonstrate cardiovascular benefit with fenofibrate beyond that already conferred by statins; however, subgroup analysis suggested that patients with high triglycerides (≥ 204 mg/dL) and low HDL-C (≤ 34 mg/dL) may have been the most likely to derive benefit [4]. Additional studies are ongoing to evaluate the impact of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk patients. PROMINENT (Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular OutcoMes by Reducing Triglycerides IN patiENts With diabeTes) is a multicenter phase III trial which will examine major cardiovascular outcomes with pemafibrate versus placebo in 10,000 patients with diabetes and dyslipidemia (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: ). In short-term trials, pemafibrate has shown good lipid efficacy and superior tolerability compared to fenofibrate [48••, 49••].

Dual PPAR-a/ϒ agonists were developed with the expectation that they could lower triglycerides similarly to fibrates (PPAR-a activity), and improve insulin sensitivity similarly to thiazolidinediones (PPAR-ϒ activity). While these agents produce favorable lipid and glycemic changes [50], robust evidence of cardiovascular benefit is lacking, and safety concerns have limited their use [51]. For instance, aleglitazar is a dual PPAR-a/ϒ agonist that did not demonstrate benefit in cardiovascular outcomes, and also caused a significant increase in gastrointestinal bleeding and renal dysfunction [51]. New PPAR agonists are under investigation for dyslipidemia [52], and elafibrinor is a dual PPAR-a/δ agonist which is also in phase III trials for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: ).

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Omega-3 fatty acid preparations containing eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and/or docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) reduce fasting and postprandial triglycerides through suppression of hepatic VLDL production [53–55]. Omega-3 fatty acids are typically used as an adjunct to diet and other therapies. Over the counter preparations have variable proportions of EPA and DHA, so prescribed capsules are preferable for triglyceride reduction as their omega-3 fatty acid content is consistently ≥ 85%. Doses of 3–4 g per day of EPA ± DHA are required to reduce triglycerides by up to 45% [56, 57]. Available preparations in the USA include combination EPA/DHA in varying proportions (Epanova, Lovaza) [58, 59], and ≥ 95% icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) [60], an ethyl ester of EPA [58–61]. EPA/DHA and icosapent ethyl are equally effective in reducing triglycerides, though the EPA/DHA formulation Lovaza may raise LDL-C modestly, and icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) has no significant effect on LDL-C [56, 57]. Epanova is the most recent EPA/DHA preparation approved by the Food and Drug Administration (2014), and it may also increase LDL-C by up to 19% [62]. The clinical relevance of this LDL-C rise with EPA/DHA formulations is unclear, and it is not accompanied by a rise in non-HDL or ApoB, which are better indicators of cardiovascular risk [63].

Outcomes trials yielded mixed results for cardiovascular benefit with the use of omega-3 fatty acids [64–66]. However, doses used in initial studies were much lower than currently recommended for hypertriglyceridemia (1 g instead of 3–4 g), and these low doses were examined on background statin therapy [64, 65]. Additionally, patients with hypertriglyceridemia were not targeted, and mean baseline triglyceride levels were ≤ 150 mg/dL among participants [64, 65]. A subsequent landmark study in Japan utilized a moderate dose of EPA ethyl esters (1.8 g) in conjunction with low-dose statin therapy versus statin therapy alone, and observed a 19% reduction in major coronary events in those receiving EPA [67]. Furthermore, the REDUCE IT trial (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl Intervention Trial) recently demonstrated a significant 25% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events in patients receiving 4 g of icosapent ethyl daily with statin therapy versus statin alone [68••]. It is worth noting that (1) most patients in REDUCE IT had diabetes (> 57%); (2) mean baseline triglycerides were 216 mg/dL; (3) mean baseline LDL-C levels were low at 74–76 mg/dL; and (4) reduction in the primary endpoint was most prominent in patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia; a pattern of high triglycerides (≥ 200 mg/dL) and low HDL-C (≤ 35 mg/dL) [68••]. REDUCE IT therefore supports the concept that while treating all patients with moderate hypertriglyceridemia may not be useful, targeting high-risk patients with diabetic dyslipidemia despite statin-optimized LDL may be of benefit.

It is important to keep in mind that cardiovascular benefit of omega-3 fatty acids may not only be mediated by triglyceride reduction, but also by their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiarrhythmic properties [69]. It remains to be determined whether other methods of triglyceride lowering will have a similar impact on cardiovascular outcomes, and the results of PROMINENT will be particularly informative in this regard.

Additional ongoing trials are investigating the effects of moderate- and high-dose omega-3 fatty acids on cardiovascular outcomes. These studies include RESPECT-EPA (Randomized trial for Evaluation in Secondary Prevention Efficacy of Combination Therapy—statin and EPA; clinical trials registry no. UMIN000012069), a secondary prevention trial in Japan exploring the combination of statin and EPA (1.8 g daily), and EVAPORATE (Effect of Vascepa on Improving Coronary Atherosclerosis in People with High Triglycerides Taking Statin Therapy; clinicalTrials.gov number, ) which will be investigating the effects of Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa), 4 g daily, on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with hypertriglyceridemia on-statin therapy. STRENGTH (Outcomes study to assess STatin Residual risk reduction with EpaNova in hiGh cardiovascular risk patienTs with Hypertriglyceridemia) is a trial that will be exploring residual cardiovascular risk reduction with 4 g daily of EPA/DHA (Epanova) and statin therapy, versus corn oil with statin therapy (clinicalTrials.gov number, ). Finally, icosabutate is a synthetic omega-3 fatty acid under development, and emerging evidence suggests that in addition to lowering triglycerides, it has antifibrotic properties which may prove beneficial in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [70•, 71•].

Niacin

Niacin, or nicotinic acid, reduces triglyceride levels and increases HDL by up to 30% when doses of 1.5–3 g daily are used [72]. Niacin can lead to a 15% reduction in LDL-C and 25% reduction in lipoprotein(a) levels [72, 73]. Fibrates are utilized more often than niacin to lower triglycerides as they are more potent and are better tolerated. Concerns have been raised regarding niacin’s tendency to worsen glycemic control [74–76], although patients with diabetes who have moderate-to-good glycemic control can use niacin safely at moderate dosages [77, 78]. Other adverse effects which may deter use of niacin include flushing and less frequently eczema-like skin rash, acanthosis nigricans, and gastrointestinal distress.

Because it lowers triglycerides, raises HDL, and decreases lipoprotein(a), which is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis not impacted by statins [79], niacin might be expected to improve patient outcomes. In older niacin trials of secondary cardiovascular prevention before the advent of statin therapy, absolute mortality reductions of 6.2 and 7.8% were demonstrated, compared to the best absolute mortality reduction of 3.5% with a statin in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study [80]. However, evidence does not suggest improved outcomes with niacin for patients on background statin therapy. The AIM-HIGH trial did not demonstrate incremental cardiovascular benefit of niacin therapy (1.5–2 g) for patients already on simvastatin ± ezetimibe. However, interpretation of this study is difficult, as it was terminated early and HDL levels in the “placebo” arm (who still received 100–200 mg niacin daily) increased more than initially anticipated, which may have masked a true benefit from niacin therapy [81]. The subsequent HPS2-THRIVE (Heart Protection Study 2-Treatment of HDL to Reduce the Incidence of Vascular Events) study of 25,673 patients was also conducted on background simvastatin ± ezetimibe therapy, and the trial examined the impact of niacin 2 g daily plus laropiprant (to reduce flushing), versus double placebo [76]. After a median follow-up of 3.9 years, the primary endpoint of first major vascular event was not significantly lower in niacin-treated patients. Patients on niacin experienced more serious adverse events including myopathy, gastrointestinal effect, rash, and an increase in infections and bleeding. This study also demonstrated unfavorable glycemic effects, with an increase in both new cases of diabetes and significant worsening of glycemic control in patients with established diabetes [76].

A possible pharmacophysiologic flaw in both AIM-HIGH and HPS2-THRIVE was bedtime niacin administration, as bedtime dosing may lead to a catecholamine surge (plausibly increasing cardiovascular risk). This possibility was circumvented by mealtime dosing utilized in earlier trials [80]. Nevertheless, these studies argue against niacin as a first-line adjunct to lower triglycerides in patients already on-statin therapy. They do not answer the question of whether niacin may improve outcomes in nonstatin-treated patients (e.g., in the case of statin intolerance).

Approach to Moderate Hypertriglyceridemia in Diabetes

Guidelines

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), fasting triglycerides of > 150, > 200, and > 500 mg/dL are seen in 31%, 16.2%, and 1.1% of US adults, respectively [82]. Many organizations have published guidelines for the diagnosis and categorization of hypertriglyceridemia, including the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) [83•]; the National Lipid Association (NLA) [84, 85•]; the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (NCEP) [86]; and the Endocrine Society (TES) [87]. These organizations agree that normal fasting triglycerides should be defined as < 150 mg/dl. Table 2 summarizes the categorization of triglyceride levels across lipid guidelines.

Table 2.

Categorization of triglyceride levels by lipid guidelines

| Categorization | AACE | NLA | NCEP | TES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | < 150 | < 150 | < 150 | < 150 |

| Borderline high (TES: Mild) | 150–199 | 150–199 | 150–199 | 150–199 |

| High (TES: Moderate) | 200–499 | 200–499 | 200–499 | 200–999 |

| Very high (TES: severe) | ≥500 | ≥500 | ≥500 | 1000–1999 |

| Very severe | N/A | N/A | N/A | ≥2000 |

Triglyceride levels are in mg/dL

AACE American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, NLA National Lipid Association, NCEP National Cholesterol Education Program, TES the Endocrine Society

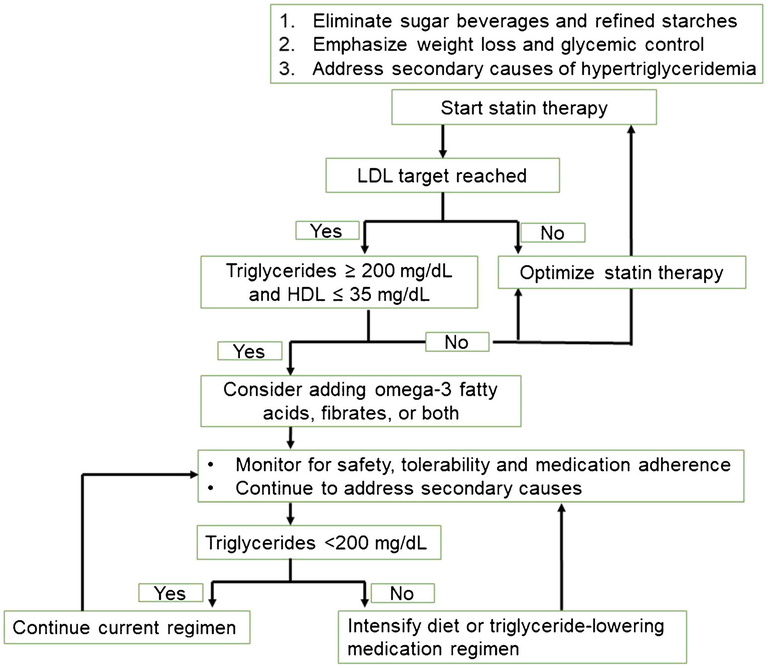

All guidelines recommend screening adults for hypertriglyceridemia as part of a complete lipid panel at least every 5 years [83•, 84, 85•, 86, 87], and AACE further advises annual screening for dyslipidemia in patients with type 1 or 2 diabetes [83•]. It is generally accepted that patients with very high/severe hypertriglyceridemia warrant both lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy due to the likelihood of unrecognized increases in triglycerides and associated pancreatitis risk [83•, 84, 85•, 86, 87]. While recent guidelines recognize heightened cardiovascular risk with moderate triglyceride elevations (typically considered 200–499 mg/dL) [85•], there remains a gap in guidance regarding approaches to modifying this risk in patients with diabetes who have sustained moderate hypertriglyceridemia despite appropriate lifestyle modifications and statin-optimized LDL. Based on recent evidence, Fig. 2 proposes an approach to managing patients with diabetes in this scenario.

Fig. 2.

Proposed approach to management of triglycerides in diabetic dyslipidemia. LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein

Triglyceride-Lowering Therapies in Development

In addition to pemafibrate, dual PPAR agonists and icosabutate mentioned above, a number of other triglyceride-lowering agents are under investigation.

Apolipoprotein CIII Inhibitors

Apolipoprotein (apo) CIII increases triglyceride levels by inhibiting LPL and reducing hepatic uptake of remnant lipoproteins [88]. Mendelian randomization studies demonstrate that variants with loss of apoCIII have lower triglyceride levels, higher HDL, and a 40% risk reduction of coronary heart disease [17, 19]. Antisense oligonucleotides, such as volanesorsen, have been developed to decrease apoCIII expression. In phase II trials of patients with type 2 diabetes and baseline hypertriglyceridemia (triglycerides 201–499 mg/dL), volanesorsen reduced apoCIII levels by 88%, triglycerides by 69%, and raised HDL by 42% compared to placebo. Volanesorsen also improved insulin sensitivity as measured by the insulin sensitivity index, and reduced glycated albumin (− 1.7%), glycated hemoglobin (− 0.44%), and fructosamine (− 38.7 μmol/L) [89•]. The ability of volanesorsen to target both dyslipidemia and insulin resistance renders it a promising agent for diabetic dyslipidemia, but thrombocytopenia and serious bleeding are concerning side effects which have so far prevented its approval by the Food and Drug Administration [90•].

Angiopoietin-Like 3 Protein Inhibitors

Angiopoietin-like 3 protein (ANGPTL3) is an endogenous inhibitor of LPL. Similar to apoCIII, loss-of-function variants have lower triglyceride and LDL levels. Evinacumab is a monoclonal antibody against ANGPTL3 which can lower fasting triglyceride levels by up to 76% and LDL by 23% in a dose-dependent manner [91•]. An antisense oligonucleotide against ANGPTL3 has also demonstrated similar results in phase I trials [92•]. So far, ANGPTL3 appears to be a promising therapeutic target, although additional phase II and III data are needed to push these therapies forward.

Conclusion

Hypertriglyceridemia is exceedingly common among patients with diabetes, and there is growing evidence that moderate triglyceride elevations are a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. While addressing glycemic control, diet, and other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia are key steps in management, there is sufficient evidence to support the addition of triglyceride-lowering therapies (particularly omega-3 fatty acids) in patients with persistently elevated triglycerides (> 200 mg/dL) and low HDL despite statin therapy. However, it is important to consider that patients with diabetes are at risk of polypharmacy, so the benefit of initiating new medications should be weighed against the risk of declining adherence to existing regimens. Ongoing studies may determine the value of lowering triglycerides and improving diabetic dyslipidemia using various pharmacotherapies, and future studies will continue to inform our approach to moderate hypertriglyceridemia in this high-risk population.

Funding Information

MJC is supported by a Career Development Award from VHA Health Services Research & Development (CDA 13–261) and acknowledges support from the Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (CIN 13–410). Additionally, research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award No. T32DK007012 (ASA).

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Macrovascular Complications in Diabetes

Conflict of Interest John R. Guyton has received research support from Sanofi, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Amarin Pharmaceuticals.

Anastasia-Stefania Alexopoulos, Ali Qamar, Kathryn Hutchins, Matthew J. Crowley, Bryan C. Batch, and John R. Guyton declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf 2011. [Accessed 12/10/2019].

- 2.••.Nichols GA, Philip S, Reynolds K, Granowitz CB, Fazio S. Increased cardiovascular risk in hypertriglyceridemic patients with statin-controlled LDL cholesterol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(8):3019–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A longitudinal cohort study demonstrating higher cardiovascular risk in statin-controlled patients with moderate triglyceride elevations.

- 3.Miller M, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Qin J, Ray KK, Braunwald E, et al. Impact of triglyceride levels beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol after acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(7):724–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, Crouse JR 3rd, Leiter LA, Linz P, et al. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1563–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, Heinonen OP, Heinsalmi P, Helo P, et al. Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(20):1237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, Best J, Scott R, Taskinen MR, et al. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9500):1849–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koskinen P, Manttari M, Manninen V, Huttunen JK, Heinonen OP, Frick MH. Coronary heart disease incidence in NIDDM patients in the Helsinki Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 1992;15(7):820–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, Fye CL, Anderson JW, Elam MB, et al. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs high-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(6):410–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott R, O’Brien R, Fulcher G, Pardy C, D’Emden M, Tse D, et al. Effects of fenofibrate treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in 9,795 individuals with type 2 diabetes and various components of the metabolic syndrome: the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(3):493–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Study. Secondary prevention by raising HDL cholesterol and reducing triglycerides in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000;102(1):21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruckert E, Labreuche J, Deplanque D, Touboul PJ, Amarenco P. Fibrates effect on cardiovascular risk is greater in patients with high triglyceride levels or atherogenic dyslipidemia profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57(2):267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toth PP, Granowitz C, Hull M, Liassou D, Anderson A, Philip S. High triglycerides are associated with increased cardiovascular events, medical costs, and resource use: a real-world administrative claims analysis of statin-treated patients with high residual cardiovascular risk. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(15):e008740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasai T, Miyauchi K, Yanagisawa N, Kajimoto K, Kubota N, Ogita M, et al. Mortality risk of triglyceride levels in patients with coronary artery disease. Heart. 2013;99(1):22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Wareham N, Bingham S, et al. Triglycerides and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158 incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29 Western prospective studies. Circulation. 2007;115(4):450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Do R, Stitziel NO, Won HH, Jorgensen AB, Duga S, Angelica Merlini P, et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature. 2015;518(7537):102–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do R, Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Gao C, Peloso GM, et al. Common variants associated with plasma triglycerides and risk for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(1):32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myocardial Infarction G, Investigators CAEC, Stitziel NO, Stirrups KE, Masca NG, Erdmann J, et al. Coding variation in ANGPTL4, LPL, and SVEP1 and the risk of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(12):1134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tg, Hdl Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project NHL, Blood I, Crosby J, Peloso GM, Auer PL, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(1):22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes MV, Asselbergs FW, Palmer TM, Drenos F, Lanktree MB, Nelson CP, et al. Mendelian randomization of blood lipids for coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(9):539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomsen M, Varbo A, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Low nonfasting triglycerides and reduced all-cause mortality: a mendelian randomization study. Clin Chem. 2014;60(5):737–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated remnant cholesterol causes both low-grade inflammation and ischemic heart disease, whereas elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol causes ischemic heart disease without inflammation. Circulation. 2013;128(12):1298–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampidonis AD, Rogdakis E, Voutsinas GE, Stravopodis DJ. The resurgence of Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL) in mammalian lipolysis. Gene. 2011;477(1–2):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginsberg HN. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(4):453–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wulffele MG, Kooy A, de Zeeuw D, Stehouwer CD, Gansevoort RT. The effect of metformin on blood pressure, plasma cholesterol and triglycerides in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Intern Med. 2004;256(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.•.Rosenblit PD. Common medications used by patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: what are their effects on the lipid profile? Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A focused review on the impact of antihyperglycemic medications on lipid profiles, including newer agents such as GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors.

- 27.Ovalle F Cardiovascular implications of antihyperglycemic therapies for type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2011;33(4):393–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.•.Szalat A, Durst R, Leitersdorf E. Managing dyslipidaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;30(3):431–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A helpful review of diabetic dyslipidemia and the impact of lifestyle and medication interventions on lipid profiles.

- 29.Chaudhuri A, Dandona P. Effects of insulin and other antihyperglycaemic agents on lipid profiles of patients with diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(10):869–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otvos JD, Mora S, Shalaurova I, Greenland P, Mackey RH, Goff DC Jr. Clinical implications of discordance between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and particle number. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(2):105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aday AW, Lawler PR, Cook NR, Ridker PM, Mora S, Pradhan AD. Lipoprotein particle profiles, standard lipids, and peripheral artery disease incidence - prospective data from the Women’s Health Study. Circulation. 2018;138(21):2330–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winkler K, Konrad T, Fullert S, Friedrich I, Destani R, Baumstark MW, et al. Pioglitazone reduces atherogenic dense LDL particles in nondiabetic patients with arterial hypertension: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(9):2588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen YH, Du L, Geng XY, Peng YL, Shen JN, Zhang YG, et al. Effects of sulfonylureas on lipids in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(3):134–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizzo M, Rizvi AA, Spinas GA, Rini GB, Berneis K. Glucose lowering and anti-atherogenic effects of incretin-based therapies: GLP-1 analogues and DPP-4-inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(10):1495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.••.Hjerpsted JB, Flint A, Brooks A, Axelsen MB, Kvist T, Blundell J. Semaglutide improves postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism, and delays first-hour gastric emptying in subjects with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(3):610–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A randomized controlled trial demonstrating reduction in both fasting and postprandial triglycerides in patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide versus placebo.

- 36.Edwards KL, Minze MG. Dulaglutide: an evidence-based review of its potential in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Core Evid. 2015;10:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farr S, Adeli K. Incretin-based therapies for treatment of postprandial dyslipidemia in insulin-resistant states. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23(1):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.•.d’Emden M, Amerena J, Deed G, Pollock C, Cooper ME. SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular benefits: transforming clinical care in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;136:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive review of SGLT2 inhibitors and their performance in cardiovascular outcomes trials.

- 39.•.Hayashi T, Fukui T, Nakanishi N, Yamamoto S, Tomoyasu M, Osamura A, et al. Dapagliflozin decreases small dense low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and increases high-density lipoprotein 2-cholesterol in patients with type 2 diabetes: comparison with sitagliptin. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A study demonstrating that while SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin may raise LDL-C, it suppresses small dense, atherogenic LDL.

- 40.Watts GF, Ooi EM, Chan DC. Demystifying the management of hypertriglyceridaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10(11):648–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.•.Williams L, Rhodes KS, Karmally W, Welstead LA, Alexander L, Sutton L, et al. Familial chylomicronemia syndrome: bringing to life dietary recommendations throughout the life span. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(4):908–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; While this paper is geared towards patients with LPL deficiency, it provides a good overview of dietary approaches to lowering triglycerides.

- 42.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):229–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faeh D, Minehira K, Schwarz JM, Periasamy R, Park S, Tappy L. Effect of fructose overfeeding and fish oil administration on hepatic de novo lipogenesis and insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes. 2005;54(7):1907–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein EA, Lane M, Laskarzewski P. Comparison of statins in hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81(4A):66B–9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenson RS, Davidson MH, Hirsh BJ, Kathiresan S, Gaudet D. Genetics and causality of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23): 2525–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro MD, Fazio S. From lipids to inflammation: new approaches to reducing atherosclerotic risk. Circ Res. 2016;118(4):732–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenson RS. Current overview of statin-induced myopathy. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):408–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.••.Araki E, Yamashita S, Arai H, Yokote K, Satoh J, Inoguchi T, et al. Effects of pemafibrate, a novel selective PPAR alpha modulator, on lipid and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertriglyceridemia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(3):538–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important phase III trial of pemafibrate in patients with T2DM and hypertriglyceridemia which demonstrated good efficacy of this new fibrate in lowering triglycerides.

- 49.••.Arai H, Yamashita S, Yokote K, Araki E, Suganami H, Ishibashi S, et al. Efficacy and safety of pemafibrate versus fenofibrate in patients with high triglyceride and low HDL cholesterol levels: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25(6):521–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important phase III trial of pemafibrate, examining the effiacy and safety of this new agent in patients with the atherogenic dyslipidemia; alongside ref 47, this trial has set the stage for the ongoing PROMINENT study.

- 50.Henry RR, Lincoff AM, Mudaliar S, Rabbia M, Chognot C, Herz M. Effect of the dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha/gamma agonist aleglitazar on risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes (SYNCHRONY): a phase II, randomised, dose-ranging study. Lancet. 2009;374(9684):126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lincoff AM, Tardif JC, Schwartz GG, Nicholls SJ, Ryden L, Neal B, et al. Effect of aleglitazar on cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the AleCardio randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong F, Xu P, Zhai Y. The opportunities and challenges of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors ligands in clinical drug discovery and development. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):E2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nestel PJ, Connor WE, Reardon MF, Connor S, Wong S, Boston R. Suppression by diets rich in fish oil of very low density lipoprotein production in man. J Clin Invest. 1984;74(1):82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris WS, Connor WE, Illingworth DR, Rothrock DW, Foster DM. Effects of fish oil on VLDL triglyceride kinetics in humans. J Lipid Res. 1990;31(9):1549–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durrington PN, Bhatnagar D, Mackness MI, Morgan J, Julier K, Khan MA, et al. An omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrate administered for one year decreased triglycerides in simvastatin treated patients with coronary heart disease and persisting hypertriglyceridaemia. Heart. 2001;85(5):544–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris WS, Ginsberg HN, Arunakul N, Shachter NS, Windsor SL, Adams M, et al. Safety and efficacy of Omacor in severe hypertriglyceridemia. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1997;4(5–6):385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bays HE, Ballantyne CM, Kastelein JJ, Isaacsohn JL, Braeckman RA, Soni PN. Eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in patients with very high triglyceride levels (from the Multi-center, plAcebo-controlled, Randomized, double-blINd, 12-week study with an open-label Extension [MARINE] trial). Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(5):682–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals. Epanova prescribing information. 2014.

- 59.GlaxoSmithKline. Lovaza prescribing information. 2015.

- 60.Amarin Corporation. Vascepa prescibing information. 2017.

- 61.Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJ, Stein E, Isaacsohn JL, Braeckman RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in statin-treated patients with persistent high triglycerides (from the ANCHOR study). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(7):984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kastelein JJ, Maki KC, Susekov A, Ezhov M, Nordestgaard BG, Machielse BN, et al. Omega-3 free fatty acids for the treatment of severe hypertriglyceridemia: the EpanoVa fOr Lowering Very high triglyceridEs (EVOLVE) trial. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8(1):94–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Backes J, Anzalone D, Hilleman D, Catini J. The clinical relevance of omega-3 fatty acids in the management of hypertriglyceridemia. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Investigators OT, Bosch J, Gerstein HC, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Dyal L, et al. n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with dysglycemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(4):309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Risk and Prevention Study Collaborative Group, Roncaglioni MC, Tombesi M, Avanzini F, Barlera S, et al. n-3 fatty acids in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1800–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manson JE, Cook NR, Christen W, Bassuk SS, Mora S, Gibson H, et al. Marine n-3 fatty acids and prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(1):23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, Ishikawa Y, et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 2007;369(9567):1090–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.••.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;380:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A recent and impactful study which showed cardiovascular benefit with icosapent ethyl in a high-risk population with moderate hypertriglyceridemia and at-goal LDL levels.

- 69.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Mehra MR, Ventura HO. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(7):585–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.•.Fraser DA, Wang X, Alonso C, Lek S, Skjaeret T, Schuppan D. Icosabutate, a novel structurally engineered fatty-acid, exhibits potent anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects in a dietary mouse model resembling progressive human NASH. [Poster]. In press 2018.; Preliminary evidence demonstrating that icosabutate may have anti-fibrotic properties.

- 71.•.Fraser DA, Thorbek DD, Allen B, Thrane SW, Skjaeret T, Friedman SL, Feigh M. A liver-targeted structurally engineered fatty acid, icosabutate, potently reduces hepatic pro-fibrotic gene expression and improves glycemic control in an obese diet-induced mouse model of NASH. [Poster]. In press 2018.; Preliminary evidence demonstrating that icosabutate may improve glycemic control as well as reduce pro-fibrotic gene expression.

- 72.Chapman MJ, Redfern JS, McGovern ME, Giral P. Niacin and fibrates in atherogenic dyslipidemia: pharmacotherapy to reduce cardiovascular risk. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126(3):314–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stein EA, Raal F. Future directions to establish lipoprotein(a) as a treatment for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30(1):101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gray DR, Morgan T, Chretien SD, Kashyap ML. Efficacy and safety of controlled-release niacin in dyslipoproteinemic veterans. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(4):252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garg A, Grundy SM. Nicotinic acid as therapy for dyslipidemia in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1990;264(6):723–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Group HTC, Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC, Parish S, Aung T, et al. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grundy SM, Vega GL, McGovern ME, Tulloch BR, Kendall DM, Fitz-Patrick D, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of once-daily niacin for the treatment of dyslipidemia associated with type 2 diabetes: results of the assessment of diabetes control and evaluation of the efficacy of niaspan trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(14):1568–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elam MB, Hunninghake DB, Davis KB, Garg R, Johnson C, Egan D, et al. Effect of niacin on lipid and lipoprotein levels and glycemic control in patients with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease: the ADMIT study: a randomized trial Arterial Disease Multiple Intervention Trial. JAMA. 2000;284(10):1263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Willeit P, Ridker PM, Nestel PJ, Simes J, Tonkin AM, Pedersen TR, et al. Baseline and on-statin treatment lipoprotein(a) levels for prediction of cardiovascular events: individual patient-data meta-analysis of statin outcome trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1311–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Superko HR, Zhao XQ, Hodis HN, Guyton JR. Niacin and heart disease prevention: engraving its tombstone is a mistake. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(6):1309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Investigators A-H, Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(24):2255–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohen JD, Cziraky MJ, Cai Q, Wallace A, Wasser T, Crouse JR, et al. 30-year trends in serum lipids among United States adults: results from the National Health and nutrition examination surveys II, III, and 1999–2006. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(7):969–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.•.Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(Suppl 2):1–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Updated AACE guidelines on the management of dyslipidemia.

- 84.Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, Orringer CE, Bays HE, Jones PH, et al. National lipid association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: part 1–full report. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(2):129–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.•.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. [Google Scholar]; Updated cardiology guidelines on the management of dyslipidemia.

- 86.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, Goldberg IJ, Sacks F, Murad MH, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2969–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ooi EM, Barrett PH, Chan DC, Watts GF. Apolipoprotein C-III: understanding an emerging cardiovascular risk factor. Clin Sci (Lond). 2008;114(10):611–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.•.Digenio A, Dunbar RL, Alexander VJ, Hompesch M, Morrow L, Lee RG, et al. Antisense-mediated lowering of plasma apolipoprotein C-III by volanesorsen improves dyslipidemia and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(8):1408–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A phase II trial in patients with diabetes and hypertriglyceridemia which showed improvements in dyslipidemia and insulin sensitivity with the use of apoCIII inhibitor volanesorsen.

- 90.•.Gaudet D, Alexander V, Arca M, Jones A, Stroes E, Bergeron J, et al. The APPROACH study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study of volanesorsen administered subcutaneously to patients with familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS). Atherosclerosis. 2017;283:e10 Abstracts. [Google Scholar]; Early evidence revealing safety concerns with the use of volanesorsen.

- 91.•.Dewey FE, Gusarova V, Dunbar RL, O’Dushlaine C, Schurmann C, Gottesman O, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of ANGPTL3 and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):211–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important phase I study highlighting the triglyceride-lowering potential of evinacumab (mAb to ANGPTL3), and its potential to decrease atherosclerosis in mice.

- 92.•.Graham MJ, Lee RG, Brandt TA, Tai LJ, Fu W, Peralta R, et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of ANGPTL3 antisense oligonucleotides. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):222–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A phase I study which demonstrated that targeting ANGPTL3 using mRNA leads to a reduction in both triglycerides, and LDL-C.