Abstract

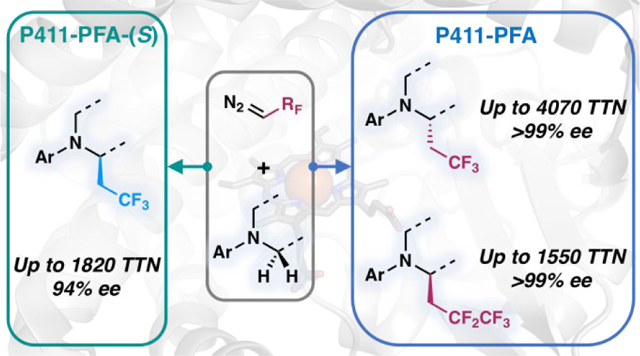

The introduction of fluoroalkyl groups into organic compounds can significantly alter pharmacological characteristics. One enabling but underexplored approach for the installation of fluoroalkyl groups is selective C(sp3)–H functionalization due to the ubiquity of C–H bonds in organic molecules. We have engineered heme enzymes that can insert fluoroalkyl carbene intermediates into α-amino C(sp3)–H bonds and enable enantiodivergent synthesis of fluoroalkyl-containing molecules. Using directed evolution, we engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes to catalyze this abiological reaction under mild conditions with total turnovers (TTN) up to 4,070 and enantiomeric excess (ee) up to 99%. The iron-heme catalyst is fully genetically-encoded and configurable by directed evolution so that just a few mutations to the enzyme completely inverted product enantioselectivity. These catalysts provide a powerful method for synthesis of chiral organofluorine molecules that is currently not possible with small-molecule catalysts.

Graphical abstract

Fluoroalkyl groups are important bioisosteres in medicinal chemistry that can enhance the metabolic stability, lipophilicity, and bioavailability of drug molecules.1 Conversion of C–H bonds into carbon-fluoroalkyl bonds represents one of the most appealing strategies for fluoroalkyl group incorporation.2 Such methods are of high atom economy and provide efficient ways to obtain new organofluorine molecules via late-stage functionalization of complex bioactive molecules.3 Despite the synthetic appeal of this strategy, however, enantioselective C(sp3)–H fluoroalkylation reactions are noticeably lacking. Major obstacles to development of transition-metal catalyzed C–H fluoroalkylation reactions are the inherent challenges associated with carbon-fluoroalkyl bond cross-coupling pathways, such as slow oxidative addition of fluoroalkyl nucleophiles4 and facile fluoride elimination of organometallic species.4b,5

A strategy involving insertion of fluoroalkylcarbene intermediates into C(sp3)–H bonds could potentially circumvent these challenges. Although metal fluoroalkylcarbene intermediates have been utilized for a number of carbene transfer reactions,5b,6 their applications for C–H functionalization have rarely been explored.7 Transition metal catalysts, including those based on rhodium8, iridium,9 copper,10 iron,11 and other metals,12 have been shown to catalyze carbene insertion into C(sp3)–H bonds. Intermolecular stereoselective reactions, however, are typically constrained to dirhodium-based catalysts with carbene precursors bearing both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents at the carbene carbon (referred to as donor-acceptor carbene reagents).8a,12a The electron-donating group is required to attenuate the high reactivity of dirhodium-carbene intermediates and offers better stereo-control of the C–H functionalization/C–C bond forming step.13 Catalysts that can use acceptor-only-type perfluorodiazoalkanes as carbene precursors for direct, enantioselective C(sp3)–H fluoroalkylation have not been reported.

Our group recently disclosed iron-heme enzymes derived from cytochromes P450 that catalyze abiological carbene C–H bond insertion reactions using several acceptor-only diazo compounds.14 Building on this effort, we now show that engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes can adopt C–H fluoroalkylation activity with high efficiency and enantioselectivity, achieving direct C–H fluoroalkylation of substrates that contain α-amino C–H bonds. Given the high prevalence of amines in pharmaceuticals, this simple biocatalytic method provides an efficient route to molecular diversification through selective C–H functionalization.

To identify a suitable starting point for directed evolution of a C–H fluoroalkylation enzyme, we first challenged a panel of 14 heme proteins in clarified Escherichia coli lysate with N-phenylpyrrolidine (1a) and 2,2,2-trifluoro-1-diazoethane (2) as model substrates under anaerobic conditions (Table S1). Several proteins, including Rhodothermus marinus cyt c (Rma cyt c), engineered Rma NOD, and wild-type P450BM3 from Bacillus megaterium, exhibited trace catalytic activities. Reactions with only the heme cofactor (iron protoporphyrin IX) as the catalyst also delivered trace amounts of product 3a. Several serine-ligated cytochromes P450 (P411s),15 however, exhibited promising initial activity for the target trifluoroethylation reaction. The highest activity (1,250 TTN) was obtained with P411-CH-C8. This P411ΔFAD variant, which comprises the heme and FMN but not the FAD domain of P450BM3, was originally engineered for carbene C–H insertion with ethyl diazoacetate (EDA).14

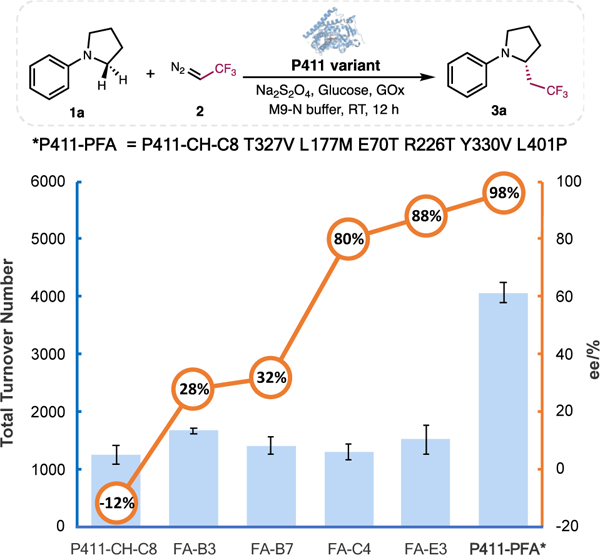

Although P411-CH-C8 exhibited high activity for the fluoroalkylation reaction between 1a and 2, the enantioselectivity of the resulting product 3a was poor (12% ee, (S)-enantiomer, Table S1). We therefore used directed evolution to increase enantioselectivity (Figure 1). We first targeted several amino acid residues in the distal heme pocket for site-saturation mutagenesis and screened for variants with improved enantioselectivity. Many of the sites selected for mutagenesis were previously shown to affect activity and selectivity in abiological carbene-and nitrene-transfer reactions (Table S2). Although none of the mutants tested showed improvement in forming (S)-3a, we discovered that a T327V mutation inverted enantioselectivity and yielded (R)-3a with 28% ee. With the T327V mutant (P411-FA-B3) as the new parent, further rounds of site-saturation mutagenesis and recombination of beneficial mutations yielded variant FA-E3 with five mutations (T327V, E70T, L177M, R226T, and Y330V) compared to P411-CH-C8. This variant exhibited 88% ee for (R)-3a.

Figure 1.

Directed evolution of P411 catalysts for C(sp3)–H fluoroalkylation reaction. Experiments were performed using clarified E. coli lysate overexpressing the P411 variants, 10 mM 1a, 20 mM 2, 25 mM D-glucose, 5 mg/mL sodium dithionite, GOx and 5 vol% EtOH in M9-N buffer at room temperature under anaerobic condition for 12 h.

We next surveyed residues in the enzyme’s proximal loop; residues in this region play an important role in regulating the oxidation activity of cytochromes P450.16 Our lab and others have shown that mutations in this region also affect abiological carbene and nitrene transfer reactivities, mainly by tuning the electron-donating properties of the heme proximal axial ligand.15,17 With FA-E3 as the parent, site-saturation mutagenesis on proximal loop residues and screening revealed the L401P mutation that further improved activity to 4,070 TTN and enantioselectivity to 98% ee (Figure 1). This final variant, named P411-PFA, contains six mutations from P411-CH-C8 (T327V, E70T, L177M, R226T, Y330V, and L401P, Figure S1).

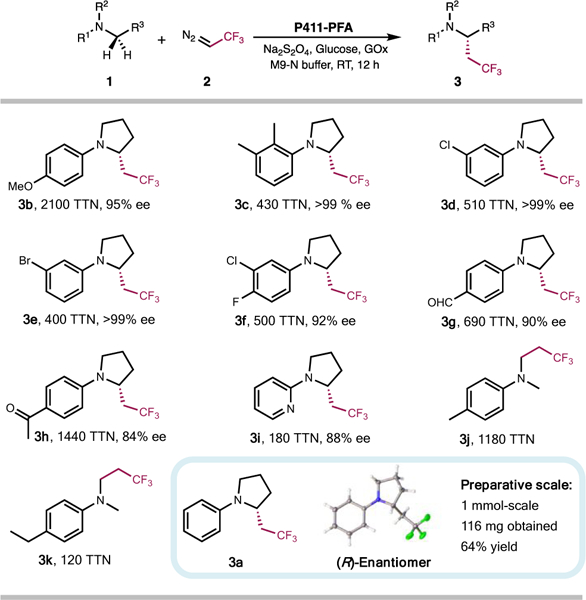

With this laboratory-evolved C–H fluoroalkylation enzyme in hand, we then explored its performance on a diverse set of substrates. As shown in Figure 2, P411-PFA could install a trifluoroethyl group onto various N-aryl pyrrolidine substrates by directly activating the α-amino C–H bonds. High activity and enantioselectivity were achieved for pyrrolidines containing a variety of N-aryl and N-heteroaryl substituents. A range of functional groups including methoxy, halogen, ketone, and aldehyde were well tolerated. The tolerance to the p-methoxylphenyl group (PMP) would enable the facile synthesis of other N-substituted pyrrolidines bearing a trifluoroethyl stereogenic center, as PMP is a well-established protecting group for the nitrogen atom and can be removed under mild conditions.18 Furthermore, given the compatibility of our method with reactive functional groups like halogens and aldehydes, the application could be broadened further by harnessing these functionalities as reaction handles to access a diverse range of structural motifs through well-established cross-coupling and condensation reactions. This enzymatic approach opens possibilities to access a broad range of chiral trifluoroethylated pyrrolidines, whose current construction methods require stepwise, successive radical cross coupling chemistry that is time-consuming and not enantioselective.19

Figure 2.

Substrate scope of P411-PFA-catalyzed C–H trifluoroethylation reaction. Absolute configuration of 3a was determined by X-ray crystallography.

In addition to pyrrolidine-type substrates, this enzymatic method could also functionalize N,N-dialkyl anilines, which is another structural motif prevalent in pharmaceuticals. The enzyme is highly selective toward α-amino C–H bonds. For instance, in compound 3k, the N-methyl is activated exclusively in the presence of weaker benzylic C–H bonds. The preference for C–H bonds at α-amino positions over those at the benzylic and OMe (3b) positions might arise from the strong electron-donating properties of nitrogen, which makes α-amino C–H bonds react more favorably with the electrophilic iron-carbene intermediates.8a,20 To further demonstrate synthetic utility, we performed this enzymatic reaction on preparative scale, where it proceeded smoothly and afforded the chiral trifluoroethylated compound 3a with 64% isolated yield and 98% ee (116 mg). We obtained the crystal structure of compound 3a, and the absolute configuration of the trifluoroethylated chiral center was determined to be R.

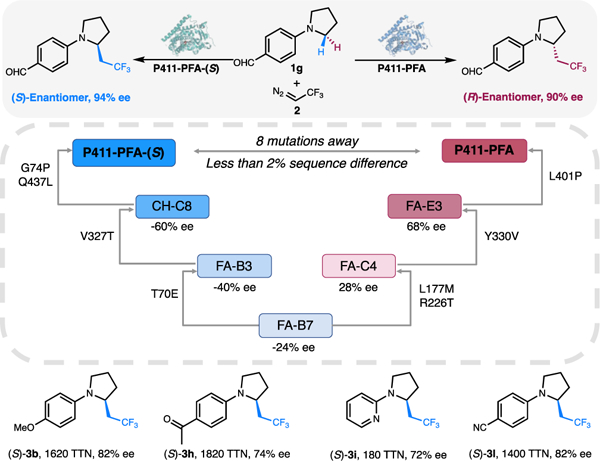

Alternate stereoisomers of a bioactive molecule can have drastically different biological effects and need to be evaluated individually during drug candidate screening.21 This necessitates the synthesis of all possible stereoisomers of a given molecule, preferably via stereo-divergent asymmetric catalysis.22 Thus we developed an enzyme catalyst that could perform the targeted C–H trifluoroethylation with enantioselectivity opposite to that of P411-PFA. To find a suitable starting point for evolving an enzyme that exhibits reversed enantioselectivity, we first evaluated the catalytic performance on various substrates of all the variants along the evolution of P411-PFA. Early variant FA-B7 exhibited moderate reversed enantioselectivity (24% ee for the (S) enantiomer) for functionalization of aldehyde-substituted N-aryl pyrrolidine substrate 1g. Further examination of variants derived from FA-B7 led to the discovery of a quadruple mutant of FA-B7 (T70E, V327T, G74P, Q437L, termed P411-PFA-(S)) that catalyzes the formation of (S)-3g with 92% ee (Figure 3, Figure S4). P411-PFA-(S) is a general catalyst for synthesis of the (S)-enantiomer of trifluoroethylated pyrrolidines, as demonstrated by its high activity and moderate-to-high (S)-enantioselectivity toward a variety of N-aryl and N-heteroaryl pyrrolidine substrates (Figure 3). These results further highlight the facile configurability of the enzymatic system for delivering diverse chiral organofluorine molecules.

Figure 3.

Enantiodivergent C(sp3)–H trifluoroethylation catalyzed by P411-PFA and P411-PFA-(S) and substrate scope of P411-PFA-(S).

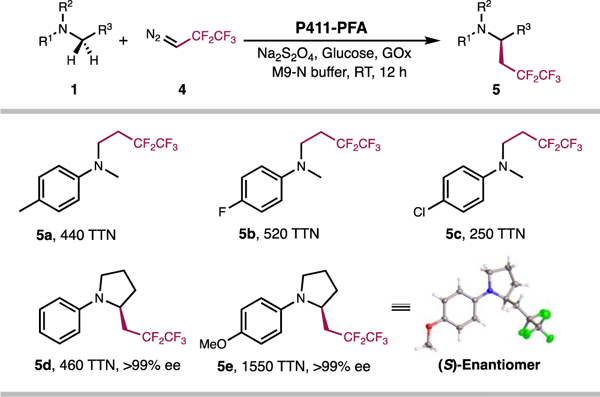

Another advantage of this chemistry is its ability to install other fluoroalkyl groups via the same C–H functionalization process. As a proof of concept, we challenged the protein catalysts with 2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoro-1-diazopropane 4 as the carbene precursor. As shown in Figure 4, P411-PFA can use 4 to introduce pentafluoropropyl groups into the α-amino C–H bonds of both acyclic and cyclic amine substrates with excellent activity and enantioselectivity. We successfully obtained 59.1 mg of the enzymatic product 5e. Intriguingly, subsequent X-ray crystallographic analysis showed that the pentafluoropropylation products obtained by P411-PFA exhibited an opposite absolute configuration to that of the trifluoroethylation ones. Although further investigation is needed to fully elucidate the origin of this inversion of absolute configuration, a potential cause is a conformational change of the corresponding fluoroalkylated heme-carbene intermediates, which alters the orientation of the fluoroalkyl groups and reverts the configuration of the prochiral face accessed by the substrates for C–H bond activation. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that carbene intermediates in heme proteins can adopt different conformations depending on their structural properties.6f,6g

Figure 4.

Substrate scope of P411-PFA-catalyzed C–H pentafluoropropylation. Absolute configuration of 5e was determined by X-ray crystallography.

In summary, we have developed a catalytic platform for insertion of fluoroalkyl-substituted carbenes into C(sp3)–H bonds with high activity and enantioselectivity under mild conditions. With directed evolution, the enantioselectivity of the enzymes can be tuned to achieve enantiodivergent synthesis of organofluorine compounds by this versatile carbene C–H insertion process. This work provides a powerful new approach for addition of fluorine-containing structural motifs prevalent in pharmaceuticals and further expands the reaction scope of new-to-nature enzymatic C–H alkylation. We envision that the enzymes developed in this research will open up new avenues for synthesis of fluorinated bioactive molecules.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences (grant MCB-1513007). X.H. is supported by an NIH pathway to independence award (Grant K99GM129419). R.K.Z. acknowledges support from the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (grant DGE-1144469) and the Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen Bioengineering Center. We thank S. Brinkmann-Chen, K. Chen, Z. Jia, S. B. J. Kan, A. M. Knight, L. J. Schaus, D. J. Wackelin, E. J. Watkins and Y. Yang for helpful discussion and comments. We also thank N. Torian, M. Shahoholi, and the Caltech Mass Spectrometry Laboratory and L. M. Henling and the Caltech X-ray Crystallography Facility for analytical support.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental details, and spectral data for all new compounds. (PDF)

X-ray crystallographic data for 3a (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data for 5e (CIF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a)Meanwell NA Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Muller K; Faeh C; Diederich F Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: Looking beyond intuition. Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Zhou Y; Wang J; Gu Z; Wang S; Zhu W; Aceña JL; Soloshonok VA; Izawa K; Liu H Next generation of fluorine-containing pharmaceuticals, compounds currently in phase II–III clinical trials of major pharmaceutical companies: new structural trends and therapeutic areas. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 422–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)Purser S; Moore PR; Swallow S; Gouverneur V Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a)Fujiwara Y; Dixon JA; O’Hara F; Funder ED; Dixon DD; Rodriguez RA; Baxter RD; Herlé B; Sach N; Collins MR; Ishihara Y; Baran PS Practical and innate carbon-hydrogen functionalization of heterocycles. Nature 2012, 492, 95–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Liang T; Neumann CN; Ritter T Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8214–8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Ma J-A; Cahard D Asymmetric fluorination, trifluoromethylation, and perfluoroalkylation reactions. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6119–6146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)McAtee RC; Beatty JW; McAtee CC; Stephenson CRJ Radical chlorodifluoromethylation: providing a motif for (hetero)arene diversification. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 3491–3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e)Beatty JW; Douglas JJ; Miller R; McAtee RC; Cole KP; Stephenson CRJ Photochemical perfluoroalkylation with pyridine N-oxides: mechanistic insights and performance on a kilogram scale. Chem 2016, 1, 456–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a)Yamaguchi J; Yamaguchi AD; Itami K C–H bond functionalization: Emerging synthetic tools for natural products and pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8960–9009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Hartwig JF Evolution of C–H bond functionalization from methane to methodology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Chu JCK; Rovis T Complementary strategies for directed C(sp3)–H functionalization: A comparison of transition-metal-catalyzed activation, hydrogen atom transfer, and carbene/nitrene transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 62–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)Zhang RK; Huang X; Arnold FH Selective C–H bond functionalization with engineered heme proteins: new tools to generate complexity. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 49, 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e)Cernak T; Dykstra KD; Tyagarajan S; Vachal P; Krska SW The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of drug-like molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 546–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f)Brooks AF; Topczewski JJ; Ichiishi N; Sanford MS; Scott PJH Late-stage [18F]fluorination: new solutions to old problems. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4545–4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a)Culkin DA; Hartwig JF Carbon–carbon bond-forming reductive elimination from arylpalladium complexes containing functionalized alkyl groups. Influence of ligand steric and electronic properties on structure, stability, and reactivity. Organometallics 2004, 23, 3398–3416. [Google Scholar]; (b)Zhao Y; Hu J Palladium-catalyzed 2,2,2-trifluoroethylation of organoboronic acids and esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1033–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a)Uneyama K; Katagiri T; Amii H α-Trifluoromethylated carbanion synthons. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 817–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Argintaru OA; Ryu D; Aron I; Molander GA Synthesis and applications of α-trifluoromethylated alkylboron compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13656–13660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Ferguson DM; Bour JR; Canty AJ; Kampf JW; Sanford MS Stoichiometric and Catalytic Aryl-Perfluoroalkyl Coupling at Tri-tert-butylphosphine Palladium(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11662–11665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a)Morandi B; Carreira EM Synthesis of trifluoroethyl-substituted ketones from aldehydes and cyclohexanones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9085–9088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Morandi B; Carreira EM Iron-catalyzed cyclopropanation with trifluoroethylamine hydrochloride and olefins in aqueous media: in situ generation of trifluoromethyl diazomethane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 938–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Hyde S; Veliks J; Liégault B; Grassi D; Taillefer M; Gouverneur V Copper-catalyzed insertion into heteroatom–hydrogen bonds with trifluorodiazoalkanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3785–3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)Luo H; Wu G; Zhang Y; Wang J Silver(I)-catalyzed N-trifluoroethylation of anilines and O-trifluoroethylation of amides with 2,2,2-trifluorodiazoethane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14503–14507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e)Liu C-B; Meng W; Li F; Wang S; Nie J; Ma J-A A facile parallel synthesis of trifluoroethyl-substituted alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6227–6230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f)Tinoco A; Steck V; Tyagi V; Fasan R Highly diastereo-and enantioselective synthesis of trifluoromethyl-substituted cyclopropanes via myoglobin-catalyzed transfer of trifluoromethylcarbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5293–5296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g)Huang X; Garcia-Borràs M; Miao K; Kan SBJ; Zutshi A; Houk KN; Arnold FH A biocatalytic platform for synthesis of chiral α-trifluoromethylated organoborons. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 270–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Duan YY; Lin JH; Xiao JC; Gu YC Fe-catalyzed insertion of fluoromethylcarbenes generated from sulfonium salts into X–H bonds (X = Si, C, P). Org. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1917–1920. [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a)Davies HML; Morton D Guiding principles for site selective and stereoselective intermolecular C–H functionalization by donor/acceptor rhodium carbenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1857–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Liao KB; Yang YF; Lie YZ; Sanders JN; Houk KN; Musaev DG; Davies HML Design of catalysts for site-selective and enantioselective functionalization of non-activated primary C–H bonds. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 1048–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Fu JT; Ren Z; Bacsa J; Musaev DG; Davies HML Desymmetrization of cyclohexanes by site-and stereoselective C–H functionalization. Nature 2018, 564, 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)Liao KB; Pickel TC; Oyarskikh VB; Acsa JB; Usaev DGM; Davies HML Site-selective and stereoselective functionalization of non-activated tertiary C–H bonds. Nature 2017, 551, 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e)Liao KB; Negretti S; Musaev DG; Bacsa J; Davies HML Site-selective and stereoselective functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds. Nature 2016, 533, 230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a)Suematsu H; Katsuki T Iridium(III) catalyzed diastereo-and enantioselective C–H bond functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14218–14219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Weldy NM; Schafer AG; Owens CP; Herting CJ; Varela-Alvarez A; Chen S; Niemeyer Z; Musaev DG; Sigman MS; Davies HML; Blakey SB Iridium(III)-bis(imidazolinyl)phenyl catalysts for enantioselective C–H functionalization with ethyl diazoacetate. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3142–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Díaz-Requejo MM; Belderraín TR; Nicasio MC; Trofimenko S; Pérez PJ Intermolecular copper-catalyzed carbon–hydrogen bond activation via carbene insertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 896–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a)Griffin JR; Wendell CI; Garwin JA; White MC Catalytic C(sp3)–H alkylation via an iron carbene intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13624–13627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Che C-M; Lo VK-Y; Zhou C-Y; Huang J-S Selective functionalisation of saturated C–H bonds with metalloporphyrin catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1950–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Zhu S-F; Zhou Q-L Iron-catalyzed transformations of diazo compounds. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2014, 1, 580–603. [Google Scholar]; (d)Li Y; Huang J-S; Zhou Z-Y; Che C-M Isolation and X-ray Crystal Structure of an Unusual Biscarbene Metal Complex and Its Reactivity toward Cyclopropanation and Allylic C–H Insertion of Unfunctionalized Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4843–4844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a)Doyle MP; Duffy R; Ratnikov M; Zhou L Catalytic carbene insertion into C–H bonds. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 704–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Wang Y; Wen X; Cui X; Zhang XP Enantioselective radical cyclization for construction of 5-membered ring structures by metalloradical C–H alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4792–4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Caballero A; Despagnet-Ayoub E; Mar Díaz-Requejo M; Díaz-Rodríguez A; González-Núñez ME; Mello R; Muñoz BK; Ojo W-S; Asensio G; Etienne M; Pérez PJ Silver-catalyzed C–C bond formation between methane and ethyl diazoacetate in supercritical CO2. Science 2011, 332, 835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)Gutiérrez-Bonet Á; Juliá-Hernández F; de Luis B; Martin R Pd-catalyzed C(sp3)–H functionalization/carbenoid Insertion: All-carbon quaternary centers via multiple C–C bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6384–6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e)Reddy AR; Zhou C-Y; Guo Z; Wei J; Che C-M Ruthenium–porphyrin-catalyzed diastereoselective intramolecular alkyl carbene insertion into C–H bonds of alkyl diazomethanes generated in situ from N-tosylhydrazones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14175–14180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hansen J; Autschbach J; Davies HML Computational study on the selectivity of donor/acceptor-substituted rhodium carbenoids. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 6555–6563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Zhang RK; Chen K; Huang X; Wohlschlager L; Renata H; Arnold FH Enzymatic assembly of carbon–carbon bonds via iron-catalysed sp3 C–H functionalization. Nature 2019, 565, 67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Coelho PS; Wang ZJ; Ener ME; Baril SA; Kannan A; Arnold FH; Brustad EM A serine-substituted P450 catalyzes highly efficient carbene transfer to olefins in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 485–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a)Poulos TL Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3919–3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Krest CM; Silakov A; Rittle J; Yosca TH; Onderko EL; Calixto JC; Green MT Significantly shorter Fe–S bond in cytochrome P450-I is consistent with greater reactivity relative to chloroperoxidase. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 696–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c)Hammer SC; Kubik G; Watkins E; Huang S; Minges H; Arnold FH Anti-Markovnikov alkene oxidation by metal-oxo-mediated enzyme catalysis. Science 2017, 358, 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d)Onderko EL; Silakov A; Yosca TH; Green MT Characterization of a selenocysteine-ligated P450 compound I reveals direct link between electron donation and reactivity. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e)Vatsis KP; Peng H-M; Coon MJ Replacement of active-site cysteine-436 by serine converts cytochrome P450 2B4 into an NADPH oxidase with negligible monooxygenase activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2002, 91, 542–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Dydio P; Key HM; Nazarenko A; Rha JYE; Seyedkazemi V; Clark DS; Hartwig JF An artificial metalloenzyme with the kinetics of native enzymes. Science 2016, 354, 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Giera DS; Sickert M; Schneider C A straightforward synthesis of (S)-anabasine via the catalytic, enantio-selective vinylogous Mukaiyama-Mannich reaction. Synthesis 2009, 2009, 3797–3802. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kawamura S; Egami H; Sodeoka M Aminotrifluoromethylation of olefins via cyclic amine formation: Mechanistic study and application to synthesis of trifluoromethylated pyrrolidines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4865–4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Salamone M; Bietti M Tuning reactivity and selectivity in hydrogen atom transfer from aliphatic C–H bonds to alkoxyl radicals: role of structural and medium effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2895–2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Shi S-L; Wong ZL; Buchwald SL Copper-catalysed enantioselective stereodivergent synthesis of amino alcohols. Nature 2016, 532, 353–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a)Krautwald S; Carreira EM Stereodivergence in asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5627–5639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b)Knight AM; Kan SBJ; Lewis RD; Brandenberg OF; Chen K; Arnold FH Diverse engineered heme proteins enable stereodivergent cyclopropanation of unactivated alkenes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 372–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.