Abstract

In medical device design, there is a vital need for a coating that promotes treatment of the patient and simultaneously prevents fouling by biomacromolecules which in turn can progress to infections, thrombosis, and other device-related complications. In this work, hydrophobin SC3 (SC3), a self-assembling amphiphilic protein, was coated on a nitric oxide (NO) releasing medical grade polymer to provide an antifouling layer to work synergistically with NO’s bactericidal and antiplatelet activity (SC3-NO). The contact angle of SC3 samples were ~30% lesser than uncoated control samples and was maintained for a month in physiological conditions, demonstrating a stable, hydrophilic coating. NO release characteristics were not adversely affected by the SC3 coating and samples with SC3 coating maintained NO release. Fibrinogen adsorption was reduced over tenfold on SC3 coated samples when compared to non-SC3 coated samples. The viable cell count of adhered bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus) on SC3-NO was 79.097 ±7.529% lesser than control samples and 49.533 ±18.18% lesser than NO samples. Platelet adherence on SC3-NO was reduced by 73.407 ±14.59% when compared to control samples and 53.202 ±25.67 when compared to NO samples. Finally, the cytocompatibility of SC3-NO was tested and proved to be safe and not trigger a cytotoxic response. The overall favorable results from the physical, chemical and biological characterization analyses demonstrate the novelty and importance of a naturally-produced antifouling layer coated on a bactericidal and antiplatelet polymer, and thus will prove to be advantageous in a multitude of medical device applications.

Keywords: nitric oxide, antifouling, hydrophobin, antimicrobial, coating

1. Introduction

In the biomaterials field, there is an increasing focus on the development of antifouling coatings to improve the biocompatibility of medical implants and devices (vascular stents and grafts, catheters, biosensors, extracorporeal circuits, etc.).1–4 Surface fouling is triggered during the first stage of the foreign body response (FBR), when non-specific proteins absorb onto the foreign surface and form a layer of extrapolymeric substance (EPS).5 This surface EPS layer provides adhesion receptors for inflammatory cells,5 bacterial cells,6 and, in blood-contact devices, platelet cells to attach to the foreign surface.7 Adhesion of these cells to the device surface can lead to device failure due to fibrous encapsulation by the FBR,8 sepsis as a result of bacteria biofilm formation,9 and occlusion of blood-contact devices from thrombus formation7 (respectively). Consequences from these various biological processes can quickly turn lethal as fouling of medical devices is a major contributor to the annual 99,000 deaths from hospital-associated infections (HAIs) in the U.S.,10 which in turn contributes to an annual expenditure of $28.4 to $33.8 billion in direct medical costs.11 In the case of blood-contact devices, occlusive thrombus formation can result in surgical complications, local tissue necrosis, or a lethal cardiovascular complication due to thrombus embolism.12–15 These severe ramifications of EPS formation is the motivation behind the research of versatile “one-for-all” materials that combine both antifouling and antimicrobial actions, which not only prevent physiological responses through prevention of protein absorption and platelet activation but can also actively kill bacteria.

Commonplace strategies to prevent surface fouling of polymer surfaces are steric repulsion,16, 17 electrostatic repulsion,18, 19 or increasing surface hydrophilicity through PEGlaytion or zwitterionic coating.19–21 These antifouling methods prevent the adsorption of foulants by increasing the thermodynamic energy needed for foulants to bind to the surface of device polymers.22, 23 While there have numerous promising publications, these methods of antifouling are mostly confined to the research setting as high cost, difficult operating procedure, and usage of environmental pollutants in the production process has made commercial scaling difficult.19 Additionally, these materials have no bioactive component and their durability in long-term biological applications has been called into question.1, 24, 25 Despite the advances in research of antifouling materials, natural biological surfaces still exhibit excellent antifouling characteristics in comparison to current commercially available medical-grade polymers.25–27 Thus investigation into alternative antifouling methods is warranted, and at the foremost of these efforts should be biomimetic mechanisms which take advantage of the strategies evolved by nature over billions of years.

Since the discovery of nitric oxide (NO) as the endothelium-derived relaxing factor, there has been a great deal of research into mimicking the physiological release of NO from the endothelium as a means of improving in vivo medical device biocompatibility.28 In the cardiovascular system, healthy endothelial cells release a low, continuous flux of NO into the bloodstream (0.5–4 × 10−10 mol cm−2min−1)29 to maintain blood vessel homeostasis by controlling blood vessel vasodilation30,31 and inhibiting platelet activation.31, 32 Additionally, white blood cells are capable of generating high fluxes of NO, which creates a highly nitrosative and oxidative microenvironment, to prevent bacterial infection.33 Numerous NO donors, such as diazeniumdiolates34, 35 and S-nitrosothiols,36, 37 have been produced and successfully integrated into various polymers in order to mimic physiological levels of NO release, thus circumventing the FBR by tricking the body into thinking NO-releasing materials are a part of the natural in vivo environment.28, 38, 39 The main limitation of these NO-releasing materials is that NO release has been shown to encourage the surface fouling of non-specific, physiological proteins.40 Once adsorbed onto the surface of medical devices, these proteins provide attachment points for cells to bind to the device surface; however, despite the increase in attachment points, NO-releasing materials have still been shown to inhibit medical device encapsulation by the FBR38, 39 and significantly reduce formation of both thrombi41–43 and biofilms in vivo.44–47

To account for this limitation, utilization of an antifouling surface coating can provide a synergistic improvement in the biocompatibility of NO-releasing materials by passively preventing surface fouling of physiological proteins while actively averting biofilm and thrombus formation. Recent studies combining NO-releasing materials with various antifouling strategies have shown a significant reduction in both biofilm formation and platelet aggregation over NO-releasing control groups;48–52 however, as previously mentioned, these various antifouling methods all have their own limitations. Thus, investigation into a biomimetic, complementing antifouling mechanism in combination with NO-releasing materials is warranted.

Hydrophobins, a type of protein produced exclusively by filamentous fungi, are considered the most surface-active class of known proteins.53, 54 An essential part of fungal growth and development,55, 56 hydrophobin proteins form self-assembled, amphiphilic monolayers at hydrophilic-hydrophobic interfaces, which alters the wettability of surfaces (changing a hydrophobic surface to hydrophilic and vice versa).54, 57–59 Of the two known classes of hydrophobins, class I hydrophobins adsorb onto surfaces in an extremely stable monolayer that can only be broken apart by high concentrations of very strong acids.58–61 The amphiphilic layer formed by class I hydrophobins has been shown to block secondary protein absorption,62 reduce adherent material on polyethylene stents,63 lower nanoscale surface friction of polymer surfaces,64 and reduce biofilm formation on polystyrene surfaces.65 Considering the ease of hydrophobin monolayer assembly, lack of harsh chemical processing, and potential for application-specific genetic or post-translational modification, the antifouling potential of hydrophobin protein, as a customizable, ecofriendly antifouling option, in combination with NO-releasing materials warrants study.

In this work, we verified the effect of hydrophobin SC3 (mentioned as SC3) concentration on surface wettability of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-incorporated silicone-base films, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and CarboSil® 2080A (Scheme 1). SC3 is a class I hydrophobin that is obtained from the wood-rotting fungus Schizophyllum commune and it is considered the most widely studied hydrophobin53, 60, 66–70. S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) was chosen as the NO donor due to its low toxicity and high retainability/storage of NO when blended or swollen into polymers.43, 46, 52, 71 PDMS is a commonly used biocompatible silicone polymer that can be cured at lower temperatures to form a crosslinked polymer capable of sustainable release of NO when swelled with SNAP,43, 71 and CarboSil® 2080A (mentioned in this work as CarboSil) is a biocompatible thermoplastic silicone-based polycarbonate urethane that can be blended with SNAP to achieve sustained NO release.49, 50 CarboSil was initially used for surface characterization measurements as it is more easily spin coated for ellipsometric and contact angle measurements. After confirming an increase in surface hydrophilicity, an SC3 concentration of 100 µg mL−1 was used to test the antifouling efficacy of self-assembled SC3 monolayers. Fibrinogen, the protein involved in thrombus formation, was used as the model protein for adhesion tests performed using spectroscopic ellipsometry measurements. Following this, SC3 was then adsorbed onto the surface of SNAP-swelled PDMS at the same 100 µg mL−1 concentration. These PDMS samples were then used to measure SC3’s effect on NO-donor behavior, through analysis of NO-release kinetics and leaching of SNAP from the polymer, to test anti-bacterial efficacy against the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), and to test the antiplatelet activity of samples incubated in platelet rich porcine plasma.

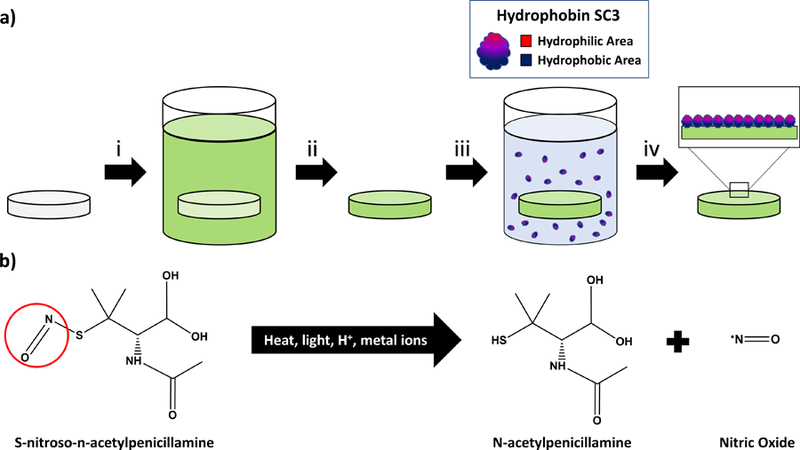

Scheme 1.

a) Fabrication of SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples. i) SNAP is swelled within PDMS using a THF solution ii) THF is evaporated out of PDMS overnight at room conditions iii) SNAP-PDMS is placed within a SC3 solution for 24 h at room conditions. iv) Samples are dried and stored for testing. b) SNAP NO-release mechanism. The SNAP nitroso group is easily broken by several catalysts to create surface NO flux.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Hydrophobin SC3 (SC3) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Steinheim, Germany). N-acetyl-d-penicillamine (NAP), sodium nitrite, concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4), tetrahydrofuran (THF), sodium phosphate monobasic (NaH2PO4), sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), potassium chloride, sodium chloride, fibrinogen from bovine plasma, and ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Luria Agar (LA) and Luria broth (LB) were purchased from Fischer BioReagents (Fair Lawn, NJ). Concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) and methanol were purchased from Fisher-Scientific (Hampton, NH). Potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4) was purchased from BDH Chemicals–VWR International (West Chester, PA). CarboSil® 2080A (mentioned as “CarboSil” hereon) was obtained from DSM Biomedical Inc. (Berkeley, CA). Milli-Q filter was used to obtain de-ionized (DI) water for the aqueous solution preparations. Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538, S. aureus) was used for all bacterial experiments. Mouse fibroblast cells (ATCC 1658) was used as the model mammalian cell for cytotoxicity assays.

2.2. Synthesis of NO donor SNAP

Synthesis of SNAP was carried out using a previously reported method.36 To summarize, a solution of 1:1 NAP in methanol and sodium nitrite was poured into an Erlenmeyer flask. After the solution was mixed, an equimolar ratio of water, 2M HCl and H2SO4 was added to the flask and stirred for 30 minutes. Once the solution was sufficiently mixed, the reaction vessel was placed in an ice bath and blown with an air stream to precipitate SNAP crystals. After 8 hours of reaction, the SNAP crystals were collected by vacuum filtration, washed with DI water, dried overnight at room temperature in a vacuum desiccator. All reagents and crystals were protected from light throughout the reaction process. After synthesis, SNAP crystals were tested for purity and stored at −20°C until their use in the experiment.

2.3. Preparation of NO-Releasing Polydimethylsiloxane

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was chosen to perform the NO release kinetics measurements and bacteria adhesion assessment due to its wide use as a biomedical polymer. A previously developed method was used to impregnate the NO donor, SNAP, into the PDMS samples.36, 43

SNAP swelling solution was prepared by dissolving SNAP in THF at a concentration of 125 mg mL-1. 0.79375 cm diameter, 0.3175 cm thick PDMS pieces were soaked in the SNAP swelling solution for 24 h on a test tube rocker. The PDMS pieces were removed, dried for 24 h in a vacuum desiccator to allow excess THF to evaporate, and then briefly sonicated for 10 minutes in PBS with EDTA buffer to remove any non-swelled SNAP present on the surface. The swelling solution and PDMS pieces were protected from light throughout the swelling process. PDMS samples were used for NO release, SNAP leaching, and bacteria studies.

2.4. Preparation of NO-Releasing CarboSil® Films

CarboSil®, a copolymer marketed by DSM Biomedical as a combination of silicone elastomers and thermoplastic polycarbonate-urethanes was chosen to be the NO-releasing base for the contact angle measurements and protein adhesion assessments. This is a copolymer that is easily spin-coated on silicon wafers and hence avoids the incorrect readings that the thinnest PDMS spin coated films (usually upwards of 200 nm thickness compared to 50 nm thickness of CarboSil® thin films) can produce on ellipsometry measurements. A thin layer of CarboSil®, with and without SNAP, was deposited on silicon wafers by spin coating. The spin coating solution was prepared by dissolving CarboSil® in THF to achieve a concentration of 1 mg mL-1. After the CarboSil® was completely dissolved, 10 wt.% of SNAP was added to the CarboSil®-THF solution. This mixture was protected from light and stirred until the SNAP crystals were dissolved completely. Using a CHEMAT Technology KW-4A spin coater, films were spin coated at 2500 rpm for 30 seconds. The resulting films formed were highly uniform with a surface thickness of 40–50 nm. These thin films were used for contact angle measurements using a Krüss DSA100 Drop Shape Analyzer (sessile drop method with deionized water) and for studying protein adhesion using an M-2000 spectroscopic ellipsometer (J.A. Woollam Co., Inc.)

2.5. Surface adsorption of Hydrophobin SC3

Solutions of hydrophobin SC3 (SC3) were prepared by sonication of SC3 in DI water. With limited hydrophobin availability, only DI water was investigated as a solvent and low concentrations of SC3 (10–100 µg) were investigated. SC3 was adsorbed onto the surface of CarboSil®-SNAP wafers and the PDMS-SNAP samples by completely covering the samples with a 100 µL aliquot of SC3 solution for 24 hours at room temperature. The thickness of the adsorbed SC3 layers for the CarboSil®-SNAP wafers were measured using an M-2000 spectroscopic ellipsometer (J.A. Woollam Co., Inc.) with a white light source at three angles of incidence (65°, 70°, and 75°) to the silicon wafer normal. This was used as a validation to ensure adsorption of SC3 to the samples as PDMS-SNAP samples were too thick and undefined in the model to be used for ellipsometric measurements.

2.6. Contact Angle Measurements

The static contact angle of CarboSil®-SNAP silicon wafers, with and without an adsorbed SC3 layer, were measured using a Krüss DSA100 Drop Shape Analyzer (sessile drop method with deionized water). Care was taken to measure the same area of the films as measured before to avoid any inconsistency in data collection. The durability of SC3 monolayer surface hydrophilicity in physiological conditions (37°C in the dark) was measured by taking the contact angle of films over a month period.

2.7. SEM

To check for hydrophobin adsorption on the surface of the materials and incorporation of the NO donor, SNAP, in the samples, scanning electron micrograph equipped with a large detector Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford Instruments) system was performed. An accelerating voltage of 5kV was applied to image the surface. All the samples were sputter coated with gold-palladium (10 nm thickness, Leica sputter coater).

2.8. Fibrinogen Adsorption Test

The thicknesses of spin-coated CarboSil® films were measured using an M-2000 spectroscopic ellipsometer (J. A. Woollam Co., Inc.) with a white light source at three angles of incidence (65°, 70°, and 75°) to the silicon wafer normal. Three replicates were used for each measurement. After the initial thickness of each film was measured, a non-saline, 7.41 pH phosphate buffer solution was prepared from 1 M sodium phosphate dibasic and 1 M potassium phosphate monobasic. Samples were incubated in the non-saline phosphate buffer (PBS) for 30 minutes at 37°C. A solution of fibrinogen from bovine plasma and non-saline PBS was prepared to achieve a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 once added to the initial non-saline PBS. After the fibrinogen solution was added, the samples were allowed to incubate at 37°C for 90 minutes. After incubation, each sample was washed with 5 mL of non-saline PBS five consecutive times followed by 5 mL of DI water five consecutive times. The slides were then dried gently with air. The thickness of the wafers after submersion in the protein solution was measured again by spectroscopic ellipsometry. Care was taken to measure the same area of the films as previously measured to avoid any inconsistency in data collection.

2.9. Nitric Oxide release measurements

Release of NO from SNAP-swelled PDMS samples was measured using a Sievers chemiluminescence Nitric Oxide Analyzer (NOA), model 280i (Boulder, CO). Prior to NO release measurements, SNAP-loaded samples with no SC3 layer were soaked in DI water at room temperature for 24 h to mimic the 24 h SC3 incubation step. PDMS samples were placed in 3 mL PBS buffer with EDTA at 37°C. NO released from the sample was constantly cleared from the buffer and headspace of the sample cell by purging the buffer with a nitrogen gas stream and bubbler. This nitrogen gas stream is then fed into the chemiluminescence detection chamber where NO levels are measured and plotted. The nitrogen flow rate was set to 200 mL min−1 with a chamber pressure of 6 Torr and an oxygen pressure of 6.2 psi. The NO release from samples was normalized by the surface area to obtain a flux unit for NO release rate (×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1).

2.9. SNAP Leaching

The weight percentage of SNAP leached from swelled PDMS samples were measured by recording the absorbance of buffer solution in time intervals of 0.5 h, 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h at 340 nm. PDMS samples were soaked in 2 mL of PBS with EDTA at 37°C. A UV-vis spectrophotometer (Thermo-Scientific Genesys 10S UV-Vis) was used to measure the absorbance of the buffer solutions at the previously mentioned time points. Absorbance measurements were taken at an optical density of 340 nm to match the UV-Vis absorbance maxima spectra for SNAP. A calibration curve of SNAP in PBS with EDTA was used to interpolate the absorbance measurements recorded from the study and convert them to concentrations of SNAP. This concentration was converted to percentage of SNAP leached by dividing the total amount of SNAP loaded in each sample used. The total SNAP in samples used was measured by placing the samples in excessive THF to leach out all remaining SNAP. The absorbance of SNAP in THF at 340nm was recorded and results were interpolated into SNAP concentrations using a calibration graph of SNAP in THF. Care was taken to make sure that buffer solution amount for each sample was maintained at the same amount throughout the experiment to avoid any inconsistent readings and three replicates were used for each measurement.

2.10. In vitro analysis of inhibition of bacteria adhesion on polymer surface

The anti-bacterial efficacy of absorbed hydrophobin SC3 was assessed using a previously used method.49 This protocol, based off E2180 American Society for Testing and Materials protocol, is designed to test the antimicrobial efficacy of hydrophobic polymers. The Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus, one of the most common causes of HAIs, was used as the model organism to test anti-bacterial efficacy of the fabricated samples.

Bacterial culture preparation:

Luria Broth (LB) medium and agar was prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions and was autoclaved prior to use in the study. Using the LB medium, S. aureus was cultured overnight in suspension at 37°C and 150 rpm in a shaker incubator. To confirm that the bacteria were in an active growth phase, the optical density (O.D.) of the culture was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Thermo-Scientific Genesys 10S UV-Vis). The culture was then centrifuged at 4400 rpm for 7.5 min and the supernatant was discarded. S. aureus cells were then washed with fresh sterile PBS (pH 7.4), by centrifuging at 4400 rpm for 7.5 min. The supernatant was discarded and fresh PBS was added to resuspend the cells. Optical density of the resuspended cells was adjusted to get a bacterial density of 106-108 CFU mL−1 of cell suspension.

Bactericidal activity analysis:

Control, SC3, NO, and SC3-NO samples were exposed to 1 mg mL−1 of fibrinogen from bovine plasma for 1 hour. After 1 h of protein exposure, the samples were exposed to S. aureus cells (106–108 CFU mL−1) at 37°C for 24 hours at a speed of 150 rpm in a shaker incubator. After 24 hours, the samples were washed with sterile PBS, to remove any unbound bacteria from the sample surface, and moved to fresh PBS. The samples were then homogenized (to remove adhered cells) for 45 seconds, vortexed (to mix cells in the solution) for 20 seconds and S. aureus was plated in the LB agar medium after preparing serial dilutions in the range of 10−1–10−5. Plated S. aureus cultures were then incubated at 37 °C for 20 hours. After 20 hours, the CFUs were counted with dilutions factored in using Equation 1, and the percentage of bacteria reduction between control groups was calculated using Equation 2. Five replicates of each sample type were used.

Following was the formula used to calculate average number of cells present on each sample per cm2.

| Equation 1) |

| Equation 2) |

2.11. Platelet adhesion assay

In order to measure the effects of surface treatment on platelet adhesion, control samples were exposed to blood plasma with a known quantity of platelets. The handling of blood was approved by the University Office of Biosafety, which oversees the University’s commitment to ethics and oversees compliance with local, state and federal regulations. All the authors received appropriate training and approval before the handling of biological materials used in this study. Freshly drawn porcine blood (Lampire Biological) with 3.9% sodium citrate at a ratio of 9:1 (blood:citrate) was used. The anticoagulated blood was centrifuged at 300 rcf for 12min using a Beckman Coulter Allegra X-30R Centrifuge. The platelet rich plasma (PRP) portion was collected carefully with a pipet as to not disturb the buffy coat. The remaining samples were then spun again at 4000 rcf for 20 min to collect platelet poor plasma (PPP). Total platelet counts of both the PRP and PPP fractions were determined using a hemocytometer (Fisher). The PRP and PPP were combined in a ratio to give a final platelet concentration 2×108 platelets mL−1. Calcium chloride (CaCl2) was added to the final platelet solution to reverse the anticoagulant (Na-citrate). The samples were placed in blood tubes and exposed to approximatively 4 mL of the calcified PRP. The tubes were then incubated at 37°C for 90min with mild rocking (25 rpm) on a Medicus Health blood tube rocker. Following the incubation, the tubes were infinitely diluted with 0.9% saline solution. The degree of platelet adhesion was determined using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released when the adherent platelets were lysed with a Triton-PBS buffer (2% v/v Triton-X-100 in PBS) using a Roche Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH). The directions were followed according to the kit’s manual. A calibration curve was constructed using known dilutions of the final PRP, and the platelet adhesion on the various tubing samples was determined from the calibration curve.

2.12. Cytocompatibility assay

The ability of SC3-NO films to generate a cytotoxic response (if any) was tested on mouse fibroblast cells using cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay in accordance with ISO 10993 standard. The CCK-8 assay is based on the reduction of highly water-soluble tetrazolium salt. WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium monosodium salt] (the tetrazolium salt) dehydrogenases in viable mammalian cells to give formazan (an orange color product) in direct proportion to the number of viable cells when detected at a wavelength 450 nm. Mouse fibroblast cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C in 75 cm2 T-flask containing premade DMEM medium (Thermo Fischer) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. After the confluency reached 80–90%, cells were removed from the flask using 0.18% trypsin and 5 mM EDTA, counted using bromophenol blue in a hemocytometer, and then 100 μL of 5000 cells mL−1 were seeded in 96 well plates. The leachates from each sample (PDMS, NO, SC3 and SC3-NO) were obtained by soaking each sample in 2mL DMEM medium for 24h at 37°C. 10μL of the CCK-8 solution was added to each well containing fibroblast cells and were incubated for 4 h. Controls cultures containing 5000 cells ml−1 were grown in 8 separate wells for reference to compare with the cells treated with leachates. Absorbance values were measured at 450 nm and the relative cell viability of mammalian cells exposed to the respective leachates were compared. 100 μL of the DMEM medium without cells was added in 3 of the wells and used as blank to adjust the background interference from DMEM media. Results were reported as percentage cell viability difference between the leachate treated cells relative to the negative control (without leachate treatment) using Equation 3.

| Equation 3) |

2.13. Statistical analysis

All data were calculated as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to calculate p values. Population standard deviation calculation was used in bacterial, platelet, and cytocompatibility analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of adsorbed surface layer of SC3

During self-assembly onto hydrophobic surfaces, SC3 undergoes an intermediate α-helical state before forming the more stable β-sheet state.59, 60 Transition to the β-sheet state can be induced by heating the sample in the presence of detergent or low pH, presence of schizophyllan in solution (a polysaccharide also produced by S. commune), or a large enough concentration of SC3 in solution for long incubation periods (≥16 h). 59, 60, 69, 70 In this study, formation of the β-sheet state was accomplished by the last listed method as it avoids high-heat processing, which causes NO release by degradation of the SNAP reservoir, and does not require extra reagents.

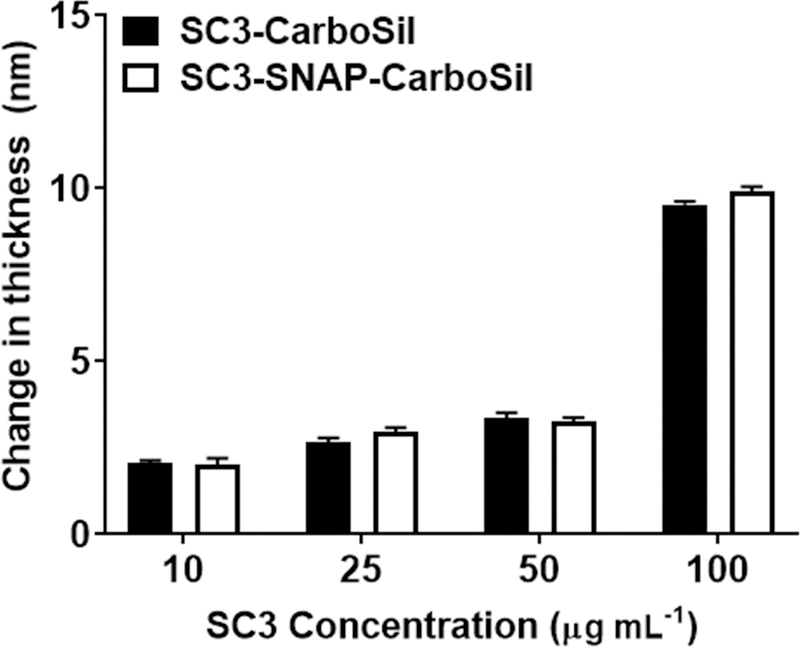

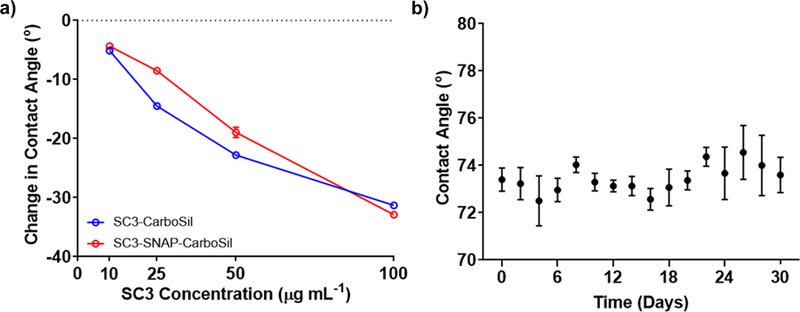

CarboSil and SNAP-blended CarboSil (SNAP-CarboSil) samples were incubated in SC3 concentrations of 10, 25, 50 and 100 µg mL−1 for 24 h at room temperature. In its spherical, α-helical state SC3 has a diameter of ~3 nm, which elongates to a length of 7–10 nm upon formation of the cylindrical, β-sheet state.53, 60, 65, 69, 70 Therefore, any change in thickness detected by ellipsometry that is greater than 7 nm signals formation of the β-sheet state. As shown in Figure 1, all SC3 concentrations less than 100 µg mL−1 failed to elongate to the β-sheet state (thicknesses between 2.00 ± .205 nm and 3.36 ± .152 nm); whereas SC3 at a concentration of 100 µg mL−1 exhibited a significant increase in surface thickness on both CarboSil and SNAP-CarboSil samples (thicknesses of 9.54 ± .286 for CarboSil and 9.91 ± .156 nm for SNAP-CarboSil), which indicates successful formation of the β-sheet state. Thereafter, the contact angle of all samples was recorded in order to validate an increase in surface hydrophilicity (Figure 2a). Non-SC3 surfaces exhibited hydrophobic behavior (106.9 ± 0.74o and 107.6 ± 1.18o for CarboSil and SNAP-CarboSil surfaces, respectively), which was altered to a hydrophilic surface upon incubation with 100 µg mL−1 SC3 (74.2 ± 0.81o and 76.12 ± 0.93o for SC3-CarboSil and SC3-SNAP-CarboSil, respectively). After confirmation of the formation of the β-sheet state and an increase in surface hydrophilicity established, an SC3 concentration of 100 µg mL−1 was used in all remaining studies. Additionally, the ability of adsorbed SC3 to retain its hydrophilicity in physiological conditions over a month period was measured by taking contact angle measurements every other day (Figure 2b). Over this month period, the SC3 layer showed no significant loss of hydrophilicity.

Figure 1.

Thickness of SC3 layers after incubation in varying concentrations of SC3 for 24 hours. A thickness of 7–10 nm suggests the formation of the β-sheet state. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Wettability after SC3 coating and storage for one month. a) Change in contact angle after incubation in varying SC3 concentration. Data shown represent mean ± SD (SD too small to be depicted for most data points, n = 3). b) Contact angle measurements of SC3 covered surface at 100 µg mL-1 for 1 month in physiological conditions (37oC in a humid environment). Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3)

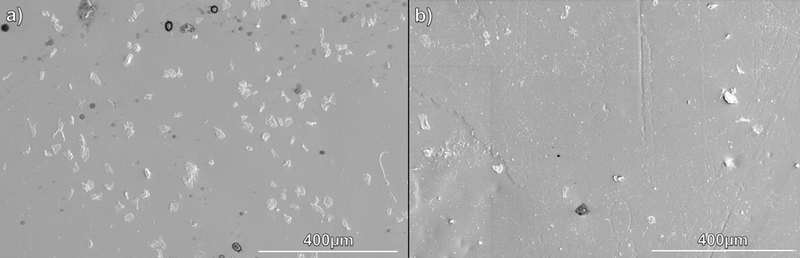

SEM images of the surface of SNAP-swelled PDMS (SNAP-PDMS) and SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples (Figure 3) were used to verify the surface coating of the SC3 on samples. From these images, it can be inferred that the SC3 coating was successfully able to coat the PDMS surface without adversely affecting the surface roughness of samples. This is a benefit of SC3 monolayer assembly as it’s known that SC3 is able to lower the friction of polymeric surfaces, and that smoother surfaces adsorb less proteins than rougher surfaces.64, 72

Figure 3.

SEM images to show the morphology of the SNAP-swelled PDMS surface uncoated and coated with SC3. A) SNAP-PDMS B) SC3-SNAP-PDMS.

3.2. SC3 effect on NO-releasing kinetics

Before testing the antifouling ability of SC3 monolayers, the effect of SC3 on NO-kinetics of SNAP-PDMS samples was measured. Previously reported methods of increasing surface hydrophilicty of NO-releasing materials has shown an increase in both NO-release and NO-donor leaching,45 which can limit application due to depeletion of the NO-donor reservoir. This increase in release and leaching is due to the fact that hydration layer formed can swell the underlying polymer. Therefore, the ideal hydrophilic coating for NO-releasing materials should have no major impact on either NO-release behavior or NO-donor leaching.49

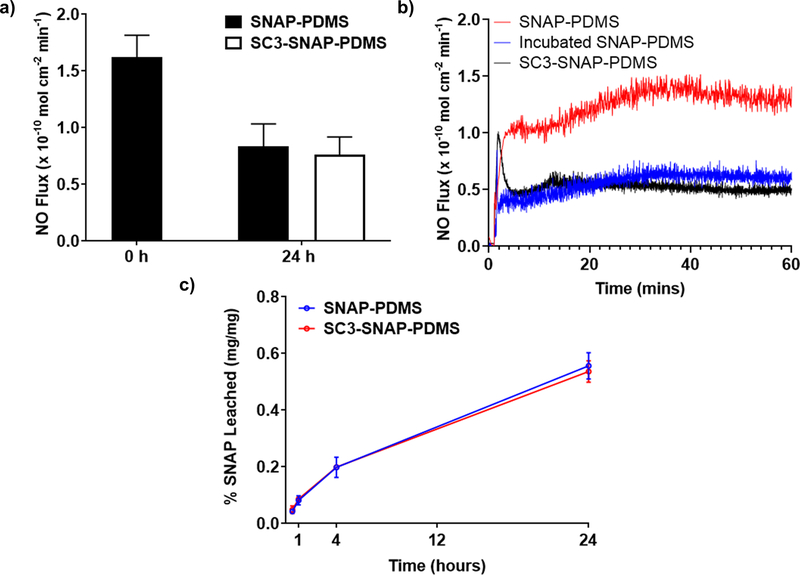

As depicted in Figure 4a & b, untreated SNAP-PDMS displayed a NO flux of 1.63 ±.233 (×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1). Thereafter, samples were placed in either DI water or a 100 µg mL−1 SC3 solution for 24 hours at room temperature. After the 24 hours, incubated SNAP-PDMS control samples exhibited a NO flux of 0.836 ± .198 (×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1), while SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples with an adsorbed SC3 layer had a slightly lower flux at 0.763 ± .155 (×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1). This data shows that the prescence of SC3 does not have a significant impact on the release of NO. After NO release measurements, a SNAP leaching study was performed to determine if the presence of adsorbed SC3 has any effect on the SNAP reservoir. The NO samples were placed in a PBS-EDTA buffer at 37°C. Figure 4c shows that, over the course of 24 h, no significant difference of SNAP leaching between SNAP-PDMS samples with and without adsorbed SC3 could be observed. These results support the notion that presence of a SC3 monolayer, despite the increase in surface hydrophilicity, has no significant effect on NO kinetics, which is a favorable quality in the design of NO-releasing materials. Similar results were observed by Liu et al., which immobilized a zwitterionic coating on an NO-releasing silicone elastomer.50 The author noted that the zwitterionic coating, which drastically increased surface hydrophilicity, was too thin to effect the overall hydrophilicity of the bulk polymer, so increase in SNAP leaching was observed.

Figure 4.

NO donor leaching and NO Release Characteristics a) NO-release before and after adsorption of SC3 under physiological conditions (soaked in PBS with EDTA buffer at 37 °C in the dark). Data represents mean ± SD (n = 4). b) 60-minute NO release profile of freshly made SNAP-PDMS, incubated SNAP-PDMS control, and SC3-SNAP-PDMS. c) SNAP content in PBS buffer due to leaching from NO-releasing polymer. Calculated as a percentage of SNAP leached into the PBS buffer from the polymer compared to total SNAP loaded. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

3.3. Assessment of physiological conditions

Fibrinogen is a glycopotein found in the blood of all vertebrates and is the precursor to the fibrin mesh that holds together platelet cells in thrombi.73, 74 Because of its high surface affinity, fibrinogen is able to replace other proteins (e.g. albumin) already adsorbed onto the surface of materials through the Vroman effect.75 Once adsorbed onto a foreign surface, fibrinogen undergoes a conformational change that results in a dramatic increase in exposure of adhesion receptors.73, 74 These adhesion receptors provide binding sites for inflammation,5 platelet,7, 74 and bacteria cells6, 76 to latch onto the device surface. Respectively, the resulting celluar attachment leads to device failure by either FBR encapsulation8 or thrombus formation7, 74 while increasing the risk severe infection due to biofilm formation.76, 77 Fibrinogen’s implication in medical device failure and biofilm formation is the reasoning behind its selection as the model protein to measure the anti-fouling capabilites of adsorbed SC3 monolayers.

CarboSil, SNAP-CarboSil, SC3-CarboSil, and SC3-SNAP-CarboSil samples were incubated in a non-saline buffer solution of fibrinogen (1 mg mL−1) for 90 minutes at 37°C to mimic the physiological environment. An incubation time of 90 minutes was chosen as the majority of proteins adsorb to medical devices surfaces within the first few minutes of exposure to physiological fluids.26 After incubation, any unattached proteins were rinsed off from the polymer surfaces by sequential washing with non-saline buffer and DI water. The change in thickness of the films was measured with a spectroscopic ellipsometer at the nanometer scale. Previous microscopic measurements of fibrinogen reveal that it is a very narrow protein with dimensions of 5–6.5 nm in diameter and 47.5 nm in length.73, 78 Therefore, for this ellipsometric study, any change in surface thickness above 5 nm would be considered adsorption of fibrinogen.

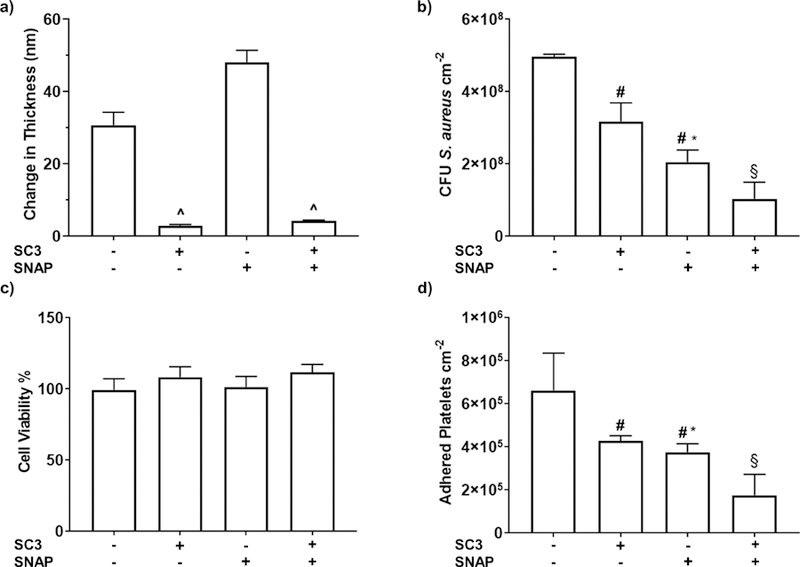

The data shown in Figure 5a shows the change in the thickness of the spin coated films after incubation in the fibrinogen solution. CarboSil samples without SC3 displayed typical in vivo polymeric medical device behavior26 with a change in surface thickness of 30.78 ± 3.53 nm for the CarboSil group and 48.15 ± 3.34 nm for the SNAP-CarboSil group, which indicates high levels of fibrinogen adsorption to the polymer surface to both. The significantly larger change in thickness seen in the SNAP-CarboSil samples over the Control group confimed the previously reported notion that NO-releasing materials adsorb more proteins.40 In comparison, SC3-CarboSil and SC3-SNAP-CarboSil samples with an adsorbed SC3 layer exhibited excellent antifouling behavior with a thickness change of 2.97 ± .299 nm and 4.24 ± .285 nm (respectively), which are both lower than the 5 nm diameter of fibrinogen. The over ten-fold decrease in fibrinogen adsorption can be attributed to three phenomena: 1) The stability of the formed SC3 monolayer due to the surface affinity of SC3’s hydrophobic portion and hydrophobic:hydrophobic/hydrophilic:hydrophilic interactions between neighboring SC3 proteins 2) The formation of a hydration layer with the surrounding environment on SC3’s hydrophilic side which increases the thermodynamic requirement for foulants to adsorb onto the surface 3) The decrease in surface roughness caused by SC3 monolayer assembly over SNAP crystals which lowers the available surface area for foulants to attach onto (Figure 3). All of these interactions combine to prevent the removal of SC3 and subsequent adsorption of fibrinogen through the Vroman effect. The slight increase in thickness observed on adsorbed SC3 surfaces could be the result of either slight swelling of the CarboSil due to the formation of a hydration layer or prescence of dust particles which, despite obest efforts, could have settled on the surface during handling.

Figure 5.

Biological characterization of SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples. a) The thickness of the EPS layer after exposure to 1 mg mL−1 fibrinogen from bovine serum for 90 minutes. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). b) Antimicrobial adhesion assay conducted with S. aureus. Calculated as a log of the colony forming units (CFU) per cm2 of surface material. Data represents mean ± SD (n = 5). c) Cytocompatibility assay exposing material leachates to mouse fibroblast cells. Reported as percent viability compared to control cells not exposed to any material leachates (n=6). d) Adhered platelet counts of samples incubated in porcine platelet-rich plasma. Data represented mean ± SD (n = 6). ^ = p < .01 vs CarboSil and SNAP-CarboSil. # = p < .05 vs PDMS. * = p <.05 vs SC3-PDMS. § = p <.01 vs PDMS, SC3-PDMS, & SNAP-PDMS.

With confirmation of SC3’s antifouling ability, the next step is to test the feasibility of the SC3-SNAP-PDMS as a medical device coating. One of the most fundamental and important antimicrobial evaluation of polymers involves the exposure of the polymer to a specific microbe for a certain period of time followed by plating of the microbial adhesion/growth extracted from the polymer. Previous studies using NO-releasing materials in combination with hydrophilic coatings have shown significant decrease in bacteria adhesion over control groups.49, 50 Thus, for this study, it was expected that SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples would also exhibit greater antibacterial efficacy over controls. This antimicrobial test was performed with S. aureus, one of the most commonly found nosocomial pathogens76, 79 with an exposure time of 24 hours. The initial exposure time is important to consider because this is when bacteria start to release exopolymeric substrates to attach to the surface of the biomaterials. From Figure 5b we can see that there was a reduction of bacteria among all the materials when compared to the untreated control group.

When compared to control PDMS samples, bacteria adhesion reduced by 36.129 ±8.510% vs. SC3-PDMS, 58.581 ±5.429% vs. SNAP-PDMS and 79.097 ±7.529% vs. SC3-SNAP-PDMS (Table 1). This result was expected as we normally see bacterial/biofilm growth in polymers with no antibacterial or antifouling polymer within 24 h. This decrease is important to establish the antimicrobial efficacy of all the fabricated surfaces when compared to the control surface. In addition to this reduction compared to control PDMS samples, significant difference in bacterial growth between the SC3-PDMS, SNAP-PDMS, and SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples were also observed. The demonstrated hydrophilic activity of the SC3 coating from previous studies (Figure 2) was validated by the reduced adhesion of bacteria on the SC3 coated samples. The hydration layer formed on the SC3 monolayer surface acted as a passive repulsion layer making it harder for bacteria to attach to the material’s surface. Hence, an initial reduction was seen when compared to control PDMS samples. However, since NO is an antibacterial agent, the bacterial adhesion reduced by 35.152 ±8.499% when comparing SNAP-PDMS to SC3-PDMS samples.

Table 1.

Comparison of bacterial adhesion in terms of percentage reduction.

| Reduction (%) ± SD | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Control vs. SC3 | 36.129 ±8.510 | 0.003 |

| Control vs. NO | 58.581 ±5.429 | 1 × 10−4 |

| Control vs. SC3-NO | 79.097 ±7.529 | 4 × 10−6 |

| SC3 vs. NO | 35.152 ±8.499 | 0.005 |

| SC3 vs. SC3-NO | 67.273 ±11.79 | 1 × 10−4 |

| NO vs. SC3-NO | 49.533 ±18.18 | 0.005 |

The most significant results are seen by combining the antifouling properties of SC3 monolayers with the bactericidal activity of NO release. The synergistic combination of SC3 monolayers and NO release in SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples significantly reduced bacteria adhesion when compared to both SC3-PDMS (67.273 ±11.788%) and SNAP-PDMS (49.533 ±18.178%) groups. This indicates and further establishes the pattern of increased antimicrobial efficacy of NO-releasing materials when combined with antifouling surfaces.

After 24 hours of exposure to S. aureus in physiological conditions, NO release measurements were taken and revealed SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples had a slightly higher flux (.476 ± .069 ×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1) compared to SNAP-PDMS samples (.445 ± .041 ×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1). While not stastically significant, considering NO-only samples had a higher NO flux than SC3-NO samples before the bacteria study (Figure 4a), this suggests presence of SC3 monolayer does not negatively affect the NO-release characteristics in the prescense of biological foulants. Therefore, it can be concluded from the aforementioned results that we were able to demonstrate a more potent antimicrobial surface with the combination of SC3 and NO release.

While it has been demonstrated that SC3-SNAP-PDMS reduces unwanted bacterial adhesion, it is of equal importance to establish that the combination does not induce a cytotoxic response when placed inside the physiological environment. To test the combination’s cytocompatibility, a CCK-8 assay was deployed utilizing mouse fibroblast cells as the model mammalian cell. Control PDMS, SC3-PDMS, SNAP-PDMS, and SC3-SNAP-PDMS leachates were collected in DMEM media and exposed to fibroblast cells. As shown in Figure 5c, there was no significant cytotoxic response observed from any of the control groups, suggesting that the SC3-SNAP-PDMS combination is safe to use in the physiological environment. It should be noted that, while not significant, SC3-PDMS and SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples exhibited a slightly proliferative effect compared to control PDMS (9.086 ±7.254% and 12.36 ±5.715% increase) and SNAP-PDMS samples (7.281 ±7.134% and 10.51 ±5.621% increase). Results are reported as a percentage compared to control cultures (not exposed to leachates).

With verification of SC3-SNAP-PDMS’s cytocompatibility in physiological environments, it is important to also assess the adhesion of physiological cells. Platelet cell adhesion to the surface of blood-contact medical devices, in combination with the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, results in the formation of thrombi.7, 73, 74 Once initiated, thrombi can rapidly form a completely occlusive clot, which can result in a multitude of severe consequences such as tissue necrosis12 or a cardiovascular event (heart attack, stroke, arrhythmia, etc.) due to an embolism of the thrombus.15 In order to prevent thrombus formation on blood-contact devices, the systemic administration of the anticoagulant heparin is standardly used; however, due to stripping the blood of its ability to clot, there are a number of complications with the systemic administration heparin that has led to heparinization as the leading cause of clinical drug-related deaths in the United States.80 Therefore, in order to reduce the risk of device failure and clinical complications, a versatile “one-for-all” biomedical material must be able to not only to prevent the adhesion of bacteria but to also prevent the adhesion of platelet cells.

Control PDMS, SC3-PDMS, SNAP-PDMS, and SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples were exposed to fresh porcine platelet rich plasma for 90 mins at 37°C under mild rocking. Thereafter, the number of adhered platelets were detached using a lysing buffer and quantified using a Roche LDH assay (Figure 5d). Similar to the results seen in the bacterial adhesion study, the hydration layer formed on the SC3-PDMS samples and antiplatelet activity of SNAP-PDMS reduced platelet adhesion compared to control samples (35.326 ±3.701% and 43.176 ±5.581%, respectively) (Table 2); however, a significant improvement is seen with the combination of mechanisms as SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples showed a significant reduction of adhered platelets compared to control PDMS samples (73.407 ±14.59%), SC3-PDMS samples (58.882 ±22.55%), and SNAP-PDMS samples (53.202 ±25.67%).

Table 2.

Comparison of platelet adhesion in terms of percentage reduction.

| Reduction (%) ± SD | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Control vs. SC3 | 35.326 ±3.701 | .03 |

| Control vs. NO | 43.176 ±5.851 | .02 |

| Control vs. SC3-NO | 73.407 ±14.59 | 3 × 10−4 |

| SC3 vs. NO | 12.138 ±9.047 | .03 |

| SC3 vs. SC3-NO | 58.882 ±22.55 | .001 |

| NO vs. SC3-NO | 53.202 ±25.67 | .003 |

4. Conclusion

In summary, the fabrication of a medical device coating containing a natural antifouling protein with NO-releasing base polymer was described for the first time. This work was able to establish the significant synergistic effects of combining passive with active strategies for antimicrobial properties. SC3 was surface coated using a simple physical strategy to provide a green alternative for antifouling method and prevent the drawbacks of NO-releasing medical device coatings. Contact angle measurements and SEM imaging verified the coating and stability of the SC3 surface for a one-month period. 100 µg/mL of SC3 coating was found to be ~9 nm in thickness and hence confirmed the formation of the more stable β-sheet state of SC3. The resulting SC3 monolayer reduced the contact angle of CarboSil samples by ~30° and was maintained for a period of 30 days in physiological conditions which indicates a durable coating. A protein adsorption test with 1 mg/mL of fibrinogen was performed in order to establish the antifouling capability of SC3 coated samples. Negligible thickness change (≤5 nm) in the films with SC3 indicated the antifouling property important for increasing bactericidal efficacy whereas samples with no SC3 showed a thickness change of as much as ~48 nm. NOA characteristics revealed that, despite the layer of hydrophilic SC3 coating, no significant effect on NO kinetics was observed, which is a favorable quality in the design of NO-releasing materials. Next, the bactericidal and antiplatelet properties were demonstrated to be superior for the SC3-SNAP-PDMS combination compared to control samples. When comparing SC3-SNAP-PDMS samples to control PDMS, SC3-PDMS, and SNAP-PDMS, bacterial adhesion was reduced by 79.097 ±7.529%, 67.273 ±11.788%, and 49.533 ±18.178% and platelet adhesion was reduced by 73.407 ±14.59%, 58.882 ±22.55%, and 53.202 ±25.67% respectively. Finally, a cytocompatibility test was performed to demonstrate that the leachates from the SC3-NO combination do not induce a cytotoxic response in mammalian cells and is safe to use for in vivo applications.

The steady physiological level of NO-release characteristics along with enhanced protein-resistance, bactericidal, antiplatelet, and cytocompatibility properties indicate a possibility of future application of this facile strategy in all medical device coatings. As SC3 is just one protein in the hydrophobin family, this study should serve as a proof-of-concept in using ecofriendly, biologically-derived surface proteins as a means of antifouling. Thus, the results of this study warrant future investigation into SC3 robustness in long-term in-vivo applications along with investigation into the antifouling nature other hydrophobin proteins.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was supported by National Institutes of Health, USA grant K25HL111213 and R01HL134899.

References

- 1.Damodaran VB and Murthy NS, Biomaterials research, 2016, 20, 18–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee I, Pangule RC and Kane RS, Advanced Materials, 2011, 23, 690–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaszykowski C, Sheikh S and Thompson M, Trends in Biotechnology, 2014, 32, 61–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Q, Zhang Y, Wang H, Brash J and Chen H, Acta Biomater, 2011, 7, 1550–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A and Chang DT, Seminars in immunology, 2008, 20, 86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart PS and Franklin MJ, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2008, 6, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorbet MB and Sefton MV, Biomaterials, 2004, 25, 5681–5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson GS and Gifford R, Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 2005, 20, 2388–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donlan RM and Costerton JW, Clinical microbiology reviews, 2002, 15, 167–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA and Cardo DM, Public Health Reports, 2007, 122, 160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott RD, 2009.

- 12.Bittl JA, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 1996, 28, 368–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D. M. J., F. W. F. M. and R. W. B., The Journal of Pathology, 1979, 127, 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies MJ and Thomas A, New England Journal of Medicine, 1984, 310, 1137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon W, Melton L and Iii, Archives of Internal Medicine, 1998, 158, 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang G, Liu M, Lin B, Cao Y and Yuan Q, Polymer, 2007, 48, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrino C, Lee S, Choi SW, Maruyama A and Spencer ND, Langmuir, 2008, 24, 8850–8856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alpert AJ, Analytical Chemistry, 2008, 80, 62–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang G.-d. and Cao Y.-m., Water Research, 2012, 46, 584–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inutsuka M, Yamada NL, Ito K and Yokoyama H, ACS Macro Letters, 2013, 2, 265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He M, Gao K, Zhou L, Jiao Z, Wu M, Cao J, You X, Cai Z, Su Y and Jiang Z, Acta Biomaterialia, 2016, 40, 142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostuni E, Chapman RG, Holmlin RE, Takayama S and Whitesides GM, Langmuir, 2001, 17, 5605–5620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Zheng J, Li L and Jiang S, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2005, 127, 14473–14478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlenoff JB, Langmuir, 2014, 30, 9625–9636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rana D and Matsuura T, Chemical Reviews, 2010, 110, 2448–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statz AR, Barron AE and Messersmith PB, Soft Matter, 2008, 4, 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Y, Liao S-C, Higuchi A, Ruaan R-C, Chu C-W and Chen W-Y, Langmuir, 2008, 24, 5453–5458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wo Y, Brisbois EJ, Bartlett RH and Meyerhoff ME, Biomaterials Science, 2016, 4, 1161–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughn MW, Kuo L and Liao JC, American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 1998, 274, H2163–H2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundberg JO, Gladwin MT and Weitzberg E, Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2015, 14, 623–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emerson M, Momi S, Paul W, Francesco PA, Page C and Gresele P, Thromb Haemost, 1999, 81, 961–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salvemini D, Currie MG and Mollace V, The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1996, 97, 2562–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akaike T and Maeda H, Immunology, 2000, 101, 300–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds MM, Hrabie JA, Oh BK, Politis JK, Citro ML, Keefer LK and Meyerhoff ME, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Z and Meyerhoff ME, Biomaterials, 2005, 26, 6506–6517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brisbois EJ, Handa H, Major TC, Bartlett RH and Meyerhoff ME, Biomaterials, 2013, 34, 6957–6966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broniowska KA, Diers AR and Hogg N, Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013, 1830, 3173–3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hetrick EM, Prichard HL, Klitzman B and Schoenfisch MH, Biomaterials, 2007, 28, 4571–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nichols SP, Koh A, Brown NL, Rose MB, Sun B, Slomberg DL, Riccio DA, Klitzman B and Schoenfisch MH, Biomaterials, 2012, 33, 6305–6312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lantvit SM, Barrett BJ and Reynolds MM, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2013, 101, 3201–3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saavedra JE, Southan GJ, Davies KM, Lundell A, Markou C, Hanson SR, Adrie C, Hurford WE, Zapol WM and Keefer LK, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 1996, 39, 4361–4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Handa H, Major TC, Brisbois EJ, Amoako KA, Meyerhoff ME and Bartlett RH, Journal of materials chemistry. B, 2014, 2, 1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brisbois EJ, Major TC, Goudie MJ, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME and Handa H, Acta biomaterialia, 2016, 37, 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nablo BJ, Prichard HL, Butler RD, Klitzman B and Schoenfisch MH, Biomaterials, 2005, 26, 6984–6990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brisbois EJ, Bayliss J, Wu J, Major TC, Xi C, Wang SC, Bartlett RH, Handa H and Meyerhoff ME, Acta biomaterialia, 2014, 10, 4136–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wo Y, Brisbois EJ, Wu J, Li Z, Major TC, Mohammed A, Wang X, Colletta A, Bull JL, Matzger AJ, Xi C, Bartlett RH and Meyerhoff ME, ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 2017, 3, 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brisbois EJ, Major TC, Goudie MJ, Meyerhoff ME, Bartlett RH and Handa H, Acta Biomaterialia, 2016, 44, 304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goudie MJ, Singha P, Hopkins SP, Brisbois EJ and Handa H, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b16819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singha P, Pant J, Goudie MJ, Workman CD and Handa H, Biomaterials Science, 2017, 5, 1246–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q, Singha P, Handa H and Locklin J, Langmuir, 2017, 33, 13105–13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Storm WL, Youn J, Reighard KP, Worley BV, Lodaya HM, Shin JH and Schoenfisch MH, Acta Biomaterialia, 2014, 10, 3442–3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goudie MJ, Pant J and Handa H, Scientific Reports, 2017, 7, 13623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Shi F, Wösten HAB, Hektor H, Poolman B and Robillard GT, Biophysical Journal, 2005, 88, 3434–3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linder MB, Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science, 2009, 14, 356–363. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wösten HAB and Wessels JGH, Mycoscience, 1997, 38, 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wessels JGH, Mycologist, 2000, 14, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ren Q, Kwan AH and Sunde M, Biopolymers, 2013, 100, 601–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piscitelli A, Cicatiello P, Gravagnuolo AM, Sorrentino I, Pezzella C and Giardina P, Biomolecules, 2017, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wösten HAB and Scholtmeijer K, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99, 1587–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scholtmeijer K, de Vocht ML, Rink R, Robillard GT and Wösten HAB, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2009, 284, 26309–26314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lo V, Ren Q, Pham C, Morris V, Kwan A and Sunde M, Nanomaterials, 2014, 4, 827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.von Vacano B, Xu R, Hirth S, Herzenstiel I, Ruckel M, Subkowski T and Baus U, Anal Bioanal Chem, 2011, 400, 2031–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weickert U, Wiesend F, Subkowski T, Eickhoff A and Reiss G, Adv Med Sci, 2011, 56, 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Misra R, Li J, Cannon GC and Morgan SE, Biomacromolecules, 2006, 7, 1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Artini M, Cicatiello P, Ricciardelli A, Papa R, Selan L, Dardano P, Tilotta M, Vrenna G, Tutino ML, Giardina P and Parrilli E, Biofouling, 2017, 33, 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Permentier HP, Rink R, Kruijtzer JA, Liskamp RM, Wosten HA, Poolman B and Robillard GT, Biophys J, 2004, 87, 1919–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Janssen MI, van Leeuwen MB, van Kooten TG, de Vries J, Dijkhuizen L and Wosten HA, Biomaterials, 2004, 25, 2731–2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zykwinska A, Guillemette T, Bouchara J-P and Cuenot S, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics, 2014, 1844, 1231–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Vocht ML, Scholtmeijer K, van der Vegte EW, de Vries OMH, Sonveaux N, Wösten HAB, Ruysschaert J-M, Hadziioannou G, Wessels JGH and Robillard GT, Biophysical Journal, 1998, 74, 2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Vocht ML, Reviakine I, Ulrich W-P, Bergsma-Schutter W, Wösten HAB, Vogel H, Brisson A, Wessels JGH and Robillard GT, Protein Science : A Publication of the Protein Society, 2002, 11, 1199–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goudie MJ, Brisbois EJ, Pant J, Thompson A, Potkay JA and Handa H, International journal of polymeric materials, 2016, 65, 769–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.An Q, Li F, Ji Y and Chen H, Journal of Membrane Science, 2011, 367, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Doolittle RF, in Fibrinogen, Thrombosis, Coagulation, and Fibrinolysis, eds. Liu CY and Chien S, Springer US, Boston, MA, 1990, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3806-6_2, pp. 25–37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kattula S, Byrnes JR and Wolberg AS, Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 2017, 37, e13–e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fuss C, Palmaz JC and Sprague EA, Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, 2001, 12, 677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bonifait L, Grignon L and Grenier D, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 74, 4969–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boland T, Latour RA and Stutzenberger FJ, in Handbook of Bacterial Adhesion: Principles, Methods, and Applications, eds. An YH and Friedman RJ, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, 2000, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-59259-224-1_2, pp. 29–41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toscano A and Santore MM, Langmuir, 2006, 22, 2588–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Otto M, Annual Review of Medicine, 2013, 64, 175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shepherd G, Mohorn P, Yacoub K and May DW, Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 2012, 46, 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]