Abstract

Objectives

Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation (RDN) has been introduced to lower blood pressure (BP) and sympathetic activity in patients with uncontrolled hypertension with at best equivocal results. It has been postulated that anatomic and procedural elements introduce unaccounted variability and yet little is known of the impact of renal anatomy and procedural parameters on BP response to RDN.

Methods

Anatomical parameters such as length and diameter were analyzed by quantitative vascular analysis and the prevalence of accessory renal arteries and renal artery disease were documented in 150 patients with resistant hypertension undergoing bilateral RDN using a mono-electrode radiofrequency catheter (Symplicity Flex, Medtronic).

Results

Accessory renal arteries and renal artery disease were present in 47 (31%) and 14 patients (9%), respectively. At 6-months, 24h-ambulatory BP was reduced by 11/6 mmHg (p<0.001 for both). Change of systolic blood pressure (SBP) was not related to the presence of accessory renal arteries (p=0.514) or renal artery disease (p=0.354). Patients with at least one main renal artery diameter ≤4 mm had a more pronounced reduction of 24h-ambulatory SBP compared to patients where both arteries were >4mm (−19 vs. −7 mmHg; p=0.043). Neither the length of the renal artery nor the number of RF ablations influenced 24h-ambulatory BP reduction at 6 months.

Conclusion

24h-ambulatory BP lowering was most pronounced in patients with smaller renal artery diameter but not related to renal artery length, accessory arteries or renal artery disease. Further, there was no dose-response relationship observed with increasing number of ablations.

Keywords: renal denervation, anatomical, procedural determinants, ambulatory blood pressure

Introduction

Catheter-based renal denervation (RDN) has been introduced to treat patients with uncontrolled hypertension[1,2]. Early uncontrolled and unblinded studies using a single-electrode catheter documented large changes in blood pressure (BP)[3–6]. The controversially discussed randomized, sham-controlled Symplicity HTN-3 trial showed no significant difference in BP reduction between patients treated with RDN or sham but confirmed safety of the intervention[7]. Most trials however only considered patients with favorable renal artery anatomy, which was defined as (i) absence of accessory renal arteries or renal atherosclerotic disease including previous angioplasty or stenting, (ii) ≥4 mm in diameter and (iii) ≥20 mm in length of the main renal artery. Almost 50% of the hypertensive patients though are considered anatomically ineligible for RDN in case the stated anatomical criteria are applied[8]. The recently published randomized, sham-controlled SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED study provided biological proof of principle for the BP lowering efficacy of RDN in patients without an accompanying antihypertensive drug therapy[9]. In the latter, anatomical eligibility criteria were less restrictive, as vessels were considered treatable with diameters from >3 mm to <8 mm and patients with accessory renal arteries were also included. Despite the positive signals observed in the SPYRAL-OFF study, it remains of utmost importance to identify patients with a high likelihood of future BP response to RDN. This study investigated the association of anatomical and procedural determinants and their impact on 24h-ambulatory BP (ABP) change.

Methods

A total of 150 hypertensive patients undergoing bilateral RDN were enrolled prospectively between March 2009 and June 2013. Eligible patients were ≥18 years and had resistant hypertension according to the European Society of Hypertension/ European Society of Cardiology guidelines (office systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg despite treatment with ≥3 antihypertensive drugs including a diuretic at maximum tolerated dose)[10]. All patients provided written informed consent and were included in the Global Symplicity Registry[6]. Local ethic committees approved the study. Participating patients underwent a complete medical history, physical examination, BP measurements and routine blood chemistry at baseline and at the subsequent follow-up after 6 months. The adherence to antihypertensive therapy was confirmed by direct questioning. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was assessed using cystatin C measurements. OBP were obtained with an automated oscillometric device (Omron HEM-705 monitor, Omron Healthcare, Vernon Hills, Illinois, USA) and were performed in concordance with the Joint National Committee VII Guidelines[11]. 24h-ambulatory blood pressure measurements (ABPM) were ascertained with an automated oscillometric device (Spacelabs 90207, Spacelabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, Washington, USA) according to the latest European Society of Cardiology guidelines[10]. Previous studies defined response to RDN as SBP reduction ≥10 mmHg in OBP or ≥5 mmHg in ABPM average after 6 months[3,4]. In the following, response to RDN is based on ABPM, unless otherwise specified.

Renal denervation and quantitative vascular analysis (QVA)

RDN was performed using the single-electrode radiofrequency (RF) Symplicity Flex catheter (Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, California, USA). All procedures were performed by experienced interventionalists who had performed at least 10 RDN procedures per year. The number of ablations and the treatment of accessory renal arteries was at the interventionalist’s discretion. Patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis diagnosed by non-invasive means were excluded in advance. Procedural data were recorded, and two experienced investigators blinded to patient’s characteristics assessed QVA using the CAAS II Research System (Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, Netherlands).

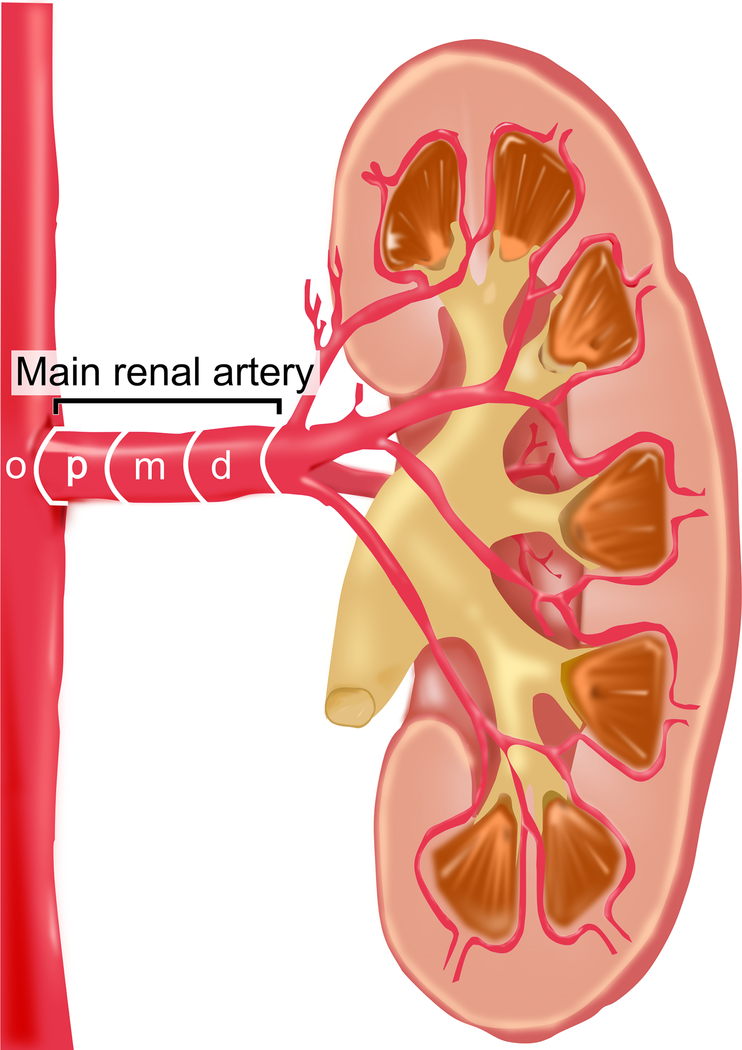

Anatomical parameters

Figure 1 depicts the nomenclature applied herein. Morphometric parameters such as minimum, mean and maximum diameter as well as length were documented for the main renal arteries and in particular for the proximal (p), middle (m) and distal (d) segments as previously described[12]. The division point in two or more consecutive branches of at least 3 mm in diameter defined the end of the main renal artery. Renal arteries other than the main renal artery were defined as accessory renal arteries. These could be of similar size and penetrating the hilus or smaller and supplying a minor part of the kidney. Accessory renal arteries were evaluated regarding mean diameter and length. For further comparisons and analysis, the largest caliber vessel of each side was determined. Renal artery disease included patients with hemodynamically non-significant renal artery stenosis (<50%) or prior renal artery interventions.

Figure 1:

Nomenclature of the renal artery

Statistical analysis

Data management and all statistical analysis were done with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as numbers (%) for categorical variables unless otherwise specified. Comparisons between groups were performed using Pearson’s χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables where appropriate. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was defined to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline patient’s characteristics are depicted in Table 1. Patients mean age was 63.8±9.7 years, 58% were male with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30.8±5.2 kg/m2. Coronary artery disease (CAD) and type 2 diabetes were diagnosed in 36 (24%) and 61 (41%) patients, respectively. Despite an average of 5.4±1.3 prescribed antihypertensive drugs, SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was 166±22 mmHg and 89±16 mmHg, respectively, with a mean heart rate of 67±11 beats per minute (bpm).

Table 1 –

Baseline characteristics

| All patients (n = 150) | Responder (n = 91) | Non-Responder (n = 59) | pValue# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 63.8±9.7 | 64.3±9.8 | 63.0±9.4 | 0.377 |

| Male gender | 87 (58%) | 51 (56%) | 36 (61%) | 0.547 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.8±5.2 | 30.6±5.5 | 31.1±4.7 | 0.526 |

| Risk factors and target organ damage | ||||

| Type II diabetes mellitus | 61 (41%) | 34 (37%) | 27 (46%) | 0.306 |

| Coronary artery disease | 36 (24%) | 24 (26%) | 12 (20%) | 0.398 |

| Cystatin C GFR, mL/(min*1.73 m2) | 77.5±31.8 | 78.5±33.1 | 76.0±29.7 | 0.542 |

| Office blood pressure and heart rate measurements | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 166.3±21.7 | 165.7±21.9 | 167.1±21.7 | 0.628 |

| DBP, mmHg | 88.5±15.5 | 88.2±15.3 | 88.9±16.1 | 0.763 |

| ISH* | 69 (46%) | 42 (46%) | 27 (46%) | 0.963 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 77.8±20.1 | 77.5±20.2 | 78.3±20.1 | 0.788 |

| Office heart rate, bpm | 66.6±10.8 | 66.8±10.8 | 66.4±11.0 | 0.896 |

| Antihypertensive treatment | ||||

| Number of antihypertensive drugs | 5.4±1.3 | 5.5±1.4 | 5.3±1.1 | 0.704 |

| ACEi/ ARB | 135 (90%) | 81 (89%) | 54 (92%) | 0.616 |

| Beta-blockers | 134 (89%) | 83 (91%) | 51 (86%) | 0.355 |

| Diuretics | 133 (89%) | 80 (88%) | 53 (90%) | 0.717 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 31 (21%) | 12 (20%) | 19 (21%) | 0.936 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 112 (75%) | 69 (76%) | 43 (73%) | 0.686 |

| Central sympatholytics | 91 (61%) | 54 (59%) | 37 (63%) | 0.680 |

| Alpha-blockers | 40 (27%) | 27 (30%) | 13 (22%) | 0.302 |

Values are means ± standard deviation or numbers (%).

p-values for comparison between responders and non-responders.

ISH indicates isolated systolic hypertension and is defined as a systolic office blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and a diastolic office blood pressure <90 mmHg.

ACE-I indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CAD, coronary artery disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; and SBP, systolic blood pressure

At 6-month follow-up, office (SBP −15±24 mmHg; DBP −7±12 mmHg, both p<0.001) and ABP (SBP −11±19 mmHg, DBP −6±12 mmHg, p<0.001) were significantly reduced. According to OBP and ABPM 59% and 61% of the patients were classified as responders, respectively (Figure 2). Except for higher 24h-ambulatory SBP in responders (+5 mmHg, p=0.035), neither patient’s characteristics nor drug regimen varied significantly between responders and non-responders at baseline (each p>0.302). In contrast, the ambulatory 24h, day- and nighttime SBP and DBP were significantly lower in responders than in non-responders at 6 months (Table 2).

Figure 2:

Change of systolic office (A) and ambulatory blood pressure (B) at 6 months. BP: Blood pressure.

Table 2 –

Ambulatory blood pressure measurement

| All patients (n = 150) | Responder (n = 91) | Non-responder (n = 59) | pValue# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| 24h SBP, mmHg | 153.5±15.3 | 155.6±15.2 | 150.3±15.1 | 0.035 |

| 24h DBP, mmHg | 85.0±13.2 | 86.4±13.1 | 82.7±13.1 | 0.060 |

| Daytime SBP, mmHg | 156.2±18.3 | 158.0±19.6 | 153.3±15.8 | 0.155 |

| Daytime DBP, mmHg | 87.2±13.7 | 88.3±13.3 | 85.5±14.2 | 0.125 |

| Nighttime SBP, mmHg | 147.0±19.9 | 147.9±19.6 | 145.6±20.5 | 0.532 |

| Nighttime DBP, mmHg | 78.9±15.0 | 79.7±14.3 | 77.6±16.0 | 0.316 |

| 6-month follow-up | ||||

| 24h SBP, mmHg | 142.5±18.5 | 133.4±14.1 | 156.4±15.7 | <0.001 |

| 24h DBP, mmHg | 79.4±12.9 | 75.2±10.7 | 85.8±13.5 | <0.001 |

| Daytime SBP, mmHg | 144.5±19.1 | 136.2±14.1 | 157.2±18.9 | <0.001 |

| Daytime DBP, mmHg | 81.4±13.6 | 77.2±11.8 | 88.0±13.6 | <0.001 |

| Nighttime SBP, mmHg | 136.1±21.9 | 127.0±17.1 | 150.2±21.1 | <0.001 |

| Nighttime DBP, mmHg | 73.7±14.3 | 69.4±12.4 | 80.4±14.6 | <0.001 |

Values are means ± standard deviation or numbers (%).

p-values for comparison between responders and non-responders. DBP indicates diastolic blood pressure and SBP, systolic blood pressure

Table 3 summarizes the anatomical parameters. Accessory renal arteries were documented in 47 patients (31%) unilaterally and 9 patients (6%) bilaterally with renal artery disease being present in 14 patients (9%). Change of 24h-ambulatory SBP was not related to the presence of accessory renal arteries (p=0.514) or renal artery disease (p=0.354). In total, 65 patients (43%) met the anatomical eligibility criteria of the Symplicity HTN studies; this rate was similar between responders and non-responders (p=0.247). Patients with at least one main renal artery ≤4 mm in diameter had a more pronounced lowering of SBP in OBP and ABPM than patients with larger caliber vessels (Figure 3). Main renal artery length (left r=−0.01, p=0.906; right r=−0.022, p=0.791) and diameter (left r=−0.118, p=0.150; right r=0.109, p=0.184) did not correlate with change of SBP in ABPM at 6 months.

Table 3 –

Procedural and anatomical parameters

| All patients (n = 150) | Responder (n = 91) | Non-responder (n = 59) | pValue# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural details | ||||

| Procedural duration, min | 66.1±23.4 | 68.4±24.1 | 62.5±22.0 | 0.098 |

| Contrast dye, mL | 85.8±38.3 | 84.0±44.0 | 88.6±27.6 | 0.063 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 10.7±6.5 | 11.2±7.8 | 10.0±3.5 | 0.624 |

| Fluoroscopy dose, cGy*cm2 | 4267±3784 | 3924±3859 | 4795±3634 | 0.037 |

| Number of ablations right side | 5.4±2.2 | 5.4±2.4 | 5.4±1.8 | 0.665 |

| Number of ablations left side | 5.1±3.0 | 5.5±3.4 | 4.4±2.0 | 0.011 |

| Total number of ablations | 10.4±4.6 | 10.9±5.4 | 9.8±2.9 | 0.209 |

| Right main renal artery (RMA) | ||||

| Renal artery disease† | 9 (6%) | 7 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 0.484 |

| Length, mm | 42.4±15.0 | 43.2±15.7 | 41.2±13.8 | 0.364 |

| Length <20 mm | 12 (8%) | 9 (10%) | 3 (5%) | 0.366 |

| Mean diameter, mm | 5.5±1.2 | 5.4±1.1 | 5.7±1.3 | 0.243 |

| Mean diameter <4 mm | 13 (9%) | 10 (11%) | 3 (5%) | 0.209 |

| Ostial diameter, mm | 6.2±1.6 | 6.1±1.6 | 6.2±1.5 | 0.763 |

| Diameter proximal segment, mm | 5.7±1.3 | 5.7±1.2 | 5.9±1.3 | 0.348 |

| Diameter middle segment, mm | 5.4±1.2 | 5.2±1.1 | 5.5±1.4 | 0.265 |

| Diameter distal segment, mm | 5.4±1.3 | 5.2±1.3 | 5.6±1.4 | 0.172 |

| Estimated surface area, mm2* | 732±305 | 733±316 | 731±291 | 0.977 |

| Left main renal artery (LMA) | ||||

| Renal artery disease† | 9 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (9%) | 0.317 |

| Length, mm | 36.6±12.3 | 37.4±12.4 | 35.4±12.2 | 0.523 |

| Length <20 mm | 9 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (9%) | 0.317 |

| Mean diameter, mm | 5.6±1.2 | 5.6±1.1 | 5.7±1.3 | 0.349 |

| Mean diameter <4 mm | 12 (8%) | 7 (8%) | 5 (9%) | 1.000 |

| Ostial diameter, mm | 6.9±1.8 | 6.8±1.8 | 7.0±1.8 | 0.589 |

| Diameter proximal segment, mm | 6.0±1.4 | 6.0±1.3 | 6.0±1.5 | 0.879 |

| Diameter middle segment, mm | 5.5±1.2 | 5.4±1.1 | 5.6±1.3 | 0.272 |

| Diameter distal segment, mm | 5.4±1.2 | 5.3±1.1 | 5.6±1.4 | 0.116 |

| Estimated surface area, mm2* | 656±280 | 667±290 | 641±266 | 0.928 |

| Symplicity HTN-3 criteria | ||||

| All criteria fulfilled | 30 (20%) | 14 (15%) | 16 (27%) | 0.079 |

| Anatomical criteria fulfilled | 65 (43%) | 36 (40%) | 29 (49%) | 0.247 |

Values are means ± standard deviation or numbers (%).

p-values for comparison between responders and non-responders.

Renal artery disease = stenosis >20%.

Estimated surface area [mm2] = π × mean diameter [mm] × length [mm]. Nomenclature based upon Figure 1.

Figure 3:

Change of systolic blood pressure at 6 months in the presence of small renal arteries (diameter unilaterally or bilaterally ≤4 mm). p-values are comparison between groups. BP: blood pressure.

A total number of 10.4±4.6 complete 120-s ablations were performed, equally distributed between both sides (p=0.106). The total number of ablations was similar in patients with and without accessory renal arteries (p=0.723). In 80% of the patients ≥4 complete 120-s ablations were performed in each main renal artery. The number of ablations per side and per mm in diameter was not affecting future change of SBP in ABPM (Figure 4). Further, change of SBP in ABPM did not correlate with the number of left-sided (r=−0.11, p=0.182), right-sided (r=0.077, p=0.349) or total number of ablations (r=−0.026, p=0.750) and neither did the length weighted number of ablations (r=0.007; p=0.936, total number of ablations per mm length of left and right main renal artery).

Figure 4:

Change of systolic blood pressure at 6 months according to number of ablations per diameter of the left (A) and right main renal artery (B). p-values are comparison between groups. BP: blood pressure.

Discussion

The available evidence suggests that RDN can reduce OBP and ABP in certain patients with uncontrolled hypertension, however with quite some variability in treatment effects[5,6,9,13]. Therefore, improving patient selection and identifying uncontrolled hypertensive individuals with a high likelihood of response has stepped into the limelight of current investigations. The present study aimed at ascertaining anatomical and procedural determinants that influence change in ABP following catheter-based RDN. The key-finding is, that patients with small main renal arteries (diameter unilaterally or bilaterally ≤4 mm) experienced a larger reduction of systolic ABPM than patients with larger caliber vessels.

Among others, an ineffective procedure is considered as one possible cause for non-response to treatment[14]. The lack of detailed knowledge of renal arterial anatomy and its relevance for subsequent response to RDN may limit success of the procedure. Furthermore, procedural data has to be evaluated systematically to refine treatment recommendations and to possibly improve RDN techniques and procedural strategies[1]. Early trials in RDN such as the Symplicity HTN studies only enrolled patients with favorable renal anatomy of >4 mm in diameter, >20 mm in length and without accessory renal arteries or renal atherosclerotic disease, excluding patients with prior interventions[3–7]. By these criteria up to 50% of the patients with hypertension are considered anatomically ineligible for catheter-based RDN[8]; the high prevalence of accessory renal arteries and renal artery disease in patients with hypertension in particular, contributes to the large share of screening exclusions. Large meta-analyses found a prevalence of 23% and 28% for accessory renal arteries[15,16]. Atherosclerotic renal artery disease and especially hemodynamically relevant renal artery stenosis is more common among patients with uncontrolled hypertension (i.e. 15–40%) compared to hypertension in general[17]. Whereas in this study group renal arteries were documented slightly more often (31%), RAD was less frequent (9%) compared to the aforementioned studies. It is important to note however, that patients with hemodynamically significant renal artery stenosis were excluded in advance by noninvasive imaging techniques. Two single-center studies found a less pronounced BP response following RDN in patients with suboptimal renal anatomy[18,19]. More challenging anatomies with difficult positioning of the mono-polar ablation catheters during ablation causing insufficient wall contact may have contributed to the discrepancy in response. The use of a helical multi-electrode catheter may address these problems and ease catheter placement. Another RDN study included patients with solitary and accessory renal arteries and documented a higher response rate in patients with solitary renal arteries compared to patients with untreated accessory renal arteries whereas there was no significant difference in response between treated and untreated accessory renal arteries[20]. Herein, response to RDN was similar in patients with and without optimal anatomy.

The vessel diameter of renal arteries is influenced by the sympathorenal axis[21]. Increased efferent sympathetic activity causes vasoconstriction by increasing renin secretion rate which subsequently reduces renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate[22]. Therefore, small renal diameters may both be consequence of reduced renal blood flow and reflect higher sympathetic tone which can potentially be affected by the means of RDN[23]. In the current study patients with at least one main renal artery ≤4 mm in mean diameter had a more pronounced reduction of systolic OBP and ABP at 6 months. The distribution of afferent and efferent nerve fibers alongside renal arteries offers a reasonable explanatory approach. A human autopsy study investigated the distribution and density of sympathetic nerves surrounding renal arteries[24]. Even though the nerve-rich target area increases with lumen diameter, the number of nerves affected by RDN decreases due to an enlarging distance between nerves and arterial lumen in larger vessels[25]. One might therefore challenge the recommendation to inject vasodilatative drugs prior to performing RDN. Further, there was no dose-response relationship between the number of complete 120-s ablations and the following reduction of BP. These findings are in line with a recent preclinical study which also lacked a clear dose-response relationship but found an improved reduction of norepinephrine spillover after ablation of distal main renal artery segments and the consecutive branches[26]. A recently published study combining the ablation of the main renal artery and its branches found an improved BP-lowering efficacy compared to patients who only had their main renal arteries treated[27]. Unfortunately, the revised approach of distally focused treatment was not investigated in the present study.

Possible limitations of our study must be discussed. First, this study was not a randomized controlled trial, therefore our findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating. Due to the study design, a potential Hawthorne effect cannot be ruled out systematically[28]. Even though patients and physicians were instructed not to change medication during the follow-up period, non-reported changes are possible and might have occurred. Adherence to the prescribed drug regimen was an inclusion criterion and hence evaluated prior to study entrance and at each visit. Nevertheless, drug adherence was not assessed by other means than direct patient questioning. Two recently published studies however indicate that adherence to antihypertensive therapy rather decreases after RDN[29,30]. As all procedures were performed with the first generation Symplicity Flex catheter (Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, California, USA), the current findings cannot be extrapolated to other catheter systems using different energy sources, number of active electrodes or catheter designs. Knowledge of the distribution and location of renal sympathetic nerve fibers has significantly evolved recently[24] and revised treatment approaches, which were not considered in the current trial.

Conclusion

The present study aimed at identifying anatomical and procedural determinants of ABP lowering following RDN using the mono-electrode RF Symplicity catheter. Patients with at least one main renal arteries of reduced diameter experienced a more pronounced reduction of 24h-ambulatory SBP. Renal artery length had no effect on BP response as was the case for the presence of accessory renal arteries or of renal artery disease. Further, there was no dose-response relationship regarding the number of ablations.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

FM, CU, and MB are supported by the Ministry of Science and Economy of the Saarland. FM is supported by the Deutsche Hochdruckliga. CU and MV are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO 196). FM and MB are supported by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie. SE, FM, MB, and CT received scientific support and speaker honorary by Medtronic, Inc. ERE was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM 49039).

References

- 1.Mahfoud F, Bohm M, Azizi M, Pathak A, Durand Zaleski I, Ewen S, et al. Proceedings from the European clinical consensus conference for renal denervation: considerations on future clinical trial design. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2219–2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahfoud F, Schmieder RE, Azizi M, Pathak A, Sievert H, Tsioufis C, et al. Proceedings from the 2nd European Clinical Consensus Conference for device-based therapies for hypertension: state of the art and considerations for the future. Eur Heart J 2017; : 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krum H, Schlaich MP, Whitbourn R, Sobotka PA, Sadowski J, Bartus K, et al. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multicentre safety and proof-of-principle cohort study. Lancet 2009; 373:1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esler MD, Bohm M, Sievert H, Rump CL, Schmieder RE, Krum H, et al. Catheter-based renal denervation for treatment of patients with treatment-resistant hypertension: 36 month results from the SYMPLICITY HTN-2 randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:1752–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azizi M, Sapoval M, Gosse P, Monge M, Bobrie G, Delsart P, et al. Optimum and stepped care standardised antihypertensive treatment with or without renal denervation for resistant hypertension (DENERHTN): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 385:1957–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohm M, Mahfoud F, Ukena C, Hoppe UC, Narkiewicz K, Negoita M, et al. First report of the Global SYMPLICITY Registry on the effect of renal artery denervation in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Hypertension 2015; 65:766–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, D’Agostino R, Flack JM, Katzen BT, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1393–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rimoldi SF, Scheidegger N, Scherrer U, Farese S, Rexhaj E, Moschovitis A, et al. Anatomical eligibility of the renal vasculature for catheter-based renal denervation in hypertensive patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend RR, Mahfoud F, Kandzari DE, Kario K, Pocock S, Weber MA, et al. Catheter-based renal denervation in patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the absence of antihypertensive medications (SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED): a randomised, sham-controlled, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet 2017; 6736:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mancia G, Fagard RH, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2013; 34:2159 LP-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewen S, Ukena C, Lüscher TF, Bergmann M, Blankestijn PJ, Blessing E, et al. Anatomical and procedural determinants of catheter-based renal denervation. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med 2016; 17:474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desch S, Okon T, Heinemann D, Kulle K, Rohnert K, Sonnabend M, et al. Randomized sham-controlled trial of renal sympathetic denervation in mild resistant hypertension. Hypertension 2015; 65:1202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahfoud F, Luscher TF. Renal denervation: symply trapped by complexity? Eur Heart J 2015; 36:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satyapal KS, Haffejee AA, Singh B, Ramsaroop L, Robbs JV, Kalideen JM. Additional renal arteries: incidence and morphometry. Surg Radiol Anat 2001; 23:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natsis K, Paraskevas G, Panagouli E, Tsaraklis A, Lolis E, Piagkou M, et al. A morphometric study of multiple renal arteries in Greek population and a systematic review. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2014; 55:1111–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Messerli FH. Secondary arterial hypertension: when, who, and how to screen? Eur Heart J 2014; 35:1245–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel B, Kirchberger M, Zeier M, Stoll F, Meder B, Saure D, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation therapy in the real world: results from the Heidelberg registry. Clin Res Cardiol 2014; 103:117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Id D, Kaltenbach B, Bertog SC, Hornung M, Hofmann I, Vaskelyte L, et al. Does the presence of accessory renal arteries affect the efficacy of renal denervation? JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013; 6:1085–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VonAchen P, Hamann J, Houghland T, Lesser JR, Wang Y, Caye D, et al. Accessory renal arteries: Prevalence in resistant hypertension and an important role in nonresponse to radiofrequency renal denervation. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med 2016; 17:470–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobotka PA, Mahfoud F, Schlaich MP, Hoppe UC, Bohm M, Krum H. Sympatho-renal axis in chronic disease. Clin Res Cardiol 2011; 100:1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiBona GF, Esler M. Translational medicine: the antihypertensive effect of renal denervation. AJP Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2010; 298:R245–R253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hering D, Lambert EA, Marusic P, Walton AS, Krum H, Lambert GW, et al. Substantial reduction in single sympathetic nerve firing after renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension. Hypertension 2013; 61:457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakakura K, Ladich E, Cheng Q, Otsuka F, Yahagi K, Fowler DR, et al. Anatomic assessment of sympathetic peri-arterial renal nerves in man. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:635–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahfoud F, Edelman ER, Böhm M. Catheter-based renal denervation is no simple matter. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:644–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahfoud F, Tunev S, Ewen S, Cremers B, Ruwart J, Schulz-Jander D, et al. Impact of lesion placement on efficacy and safety of catheter-based radiofrequency renal denervation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66:1766–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fengler K, Ewen S, Höllriegel R, Rommel K, Kulenthiran S, Lauder L, et al. Blood pressure response to main renal artery and combined main renal artery plus branch renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6:e006196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67:267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ewen S, Meyer MR, Cremers B, Laufs U, Helfer AG, Linz D, et al. Blood pressure reductions following catheter-based renal denervation are not related to improvements in adherence to antihypertensive drugs measured by urine/plasma toxicological analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2015; 104:1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmieder RE, Ott C, Schmid A, Friedrich S, Kistner I, Ditting T, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medication in treatment-resistant hypertension undergoing renal denervation. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]