Abstract

Nanotechnology, which has already revolutionised many technological areas, is expected to transform life sciences. In this sense, nanomedicine could address some of the most important limitations of conventional medicine. In general, nanomedicine include three major objectives: (1) trap and protect a great amount of therapeutic agents; (2) carry them to the specific site of disease avoiding any leakage; and (3) release on-demand high local concentrations of therapeutic agents. This feature article will make special emphasis on mesoporous silica nanoparticles that release their therapeutic cargo in response to ultrasound.

1. Introduction

Nanomedicine, the application of nanotechnology to medicine, has attracted the attention of the research community in the last few years. Among all the available nanomaterials, nanoparticles (NPs) for drug delivery are the most investigated due to the possibility of transporting and releasing therapeutic agents in a controlled manner, overcoming many limitations of conventional therapies.1,2

Researchers in biotechnology have developed many different types of NPs, both organic and inorganic. Among them, those NPs made of silica have become very popular due to their robustness. Silica quantum dots (C-dots from Cornell University) are currently under evaluation in clinical trials in patients with metastatic melanoma for cancer imaging.3 However, the adsorption capacity of C-dots is limited, which restricts their use as drug delivery systems. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) are also made of silica but with a porous structure that allows introducing therapeutic agents in their network of cavities. Additionally, it is possible to design MSNs with stimuli-responsive behaviour, which allows tailoring the release profiles with spatial, temporal and dosage control. The present Feature Article will focus on the recent developments on MSNs responsive to ultrasound.

2. Mesoporous materials

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the catalyst industry was demanding porous materials with larger pores than those from zeolites. Consequently, the pioneering reports on the synthesis of mesoporous silica materials (MSMs) were published.4,5,6 This new family of materials was characterised by an ordered distribution of the pores, which presented homogeneous sizes within a range of 2 and 10 nm; a great pore volume, ca. 1 cm3/g, and a huge surface area, up to 1000 m2/g. Those characteristics made MSMs potentially useful in those processes that might require the adsorption of molecules. In fact, the number of applications has grown exponentially since the early 1990s, as revealed by the number of publications on Mesoporous Materials in the last few years (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Number of publications on Mesoporous Materials in the last few years (more than 130,000 publications). Source: Google Scholar.

2.1. Synthesis

The synthesis of MSMs is based on the sol-gel process through the condensation of silica precursors around a template formed by self-assembled surfactant molecules. Then, the template removal through thermal methods or solvent extraction leads to a material full of network of cavities. Obviously, the nature and chemical composition of the surfactant molecules together with the concentration and temperature of the synthetic process will influence on the shape and size of the micelles formed (different liquid crystal mesophases and morphologies) and, consequently, on the mesostructure of the MSM (e.g., disordered, wormhole-like, hexagonal, cubic, and lamellar mesophases).7 This is one of the most interesting aspects of this synthetic path, because controlling the micelles formation is possible to control the final mesostructure of the porous material, which would determine the physico-chemical properties of the product.

There are many different types of MSNs that have been produced following the above mentioned synthetic route. Although the synthesis of porous silica was originally patented in the 1960s, mesoporous silica materials were first described by Kuroda and co-workers in 1990.4 Then, the subsequent work of the Mobil Oil Corporation Laboratories brought the MSM family of mesoporous materials.5,6 During the last few years many different MSMs have been produced with uniform pore size and texture.8,9 As mentioned above, the current synthetic procedures of MSMs are normally based on the use of surfactants as structure directing agents. Those synthesis methods include the sol-gel process, microwave synthesis, hydrothermal synthesis, template synthesis, modified aerogel methods, soft and hard templating methods, and fast self-assembly.10

2.2. Funtionalisation

As it has been mentioned above, the adsorption of molecules is one of the most promising applications of MSMs. Adsorption is a surface phenomenon strongly influenced by the potential host-guest interaction. In this sense, the chemistry of the surface of MSMs can be easily tuned through the functionalisation of the silanol groups present at the surface.11 In fact, there are many surface modification strategies that allow the covalent attachment of almost any functional group.12 The host-guest interaction can be designed to favour certain processes, such as slow down the cargo release, maximise the loading capacity, etc. This great versatility has fuelled the use of MSMs for many different applications, such as catalysts, sensors, optical products, environmental applications and biomedicine.13,14,15

2.3. Biomedical applications

In 2001, taking into account the great adsorption capabilities of MSMs and the possibility to control the host-guest interactions, prof. Vallet-Regí proposed MSMs as drug delivery systems for the first time.13 Since then, a great variety of therapeutic agents have been loaded into MSMs for different biomedical applications, such as drug delivery, imaging or theranostics.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23

3. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery

Although MSM were initially proposed as bulk materials for drug delivery, it did not take very long to develop nanoparticles with the same textural characteristics. The morphology and dimensions of the produced materials can be controlled through the kinetics of the sol-gel chemistry, such as reaction temperature, water content, or pH. In fact, it is possible to tailor the size, mesostructure and morphology of the produced material through the careful control of the template self-assembly and silica condensation rate.24 They were called mesoporous silica nanoparticles and presented diameters between 100 and 150 nm.25,26,27,28 MSNs were initially reported by Cai,25 Mann26 and Ostafin27 research groups. Then, Victor Lin popularised the term mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their use for drug delivery applications.28 The synthetic procedure of MSNs is based on small modifications to the above mentioned MSMs synthetic path, such as the pH of the reaction mixture, the type of surfactants and co-polymers employed and the concentration and sources of the silica precursors employed.24 Those nanoparticles were originally designed for many different applications such as adsorption,29 catalysis,30 chemical separations,31 imaging,32 targeting,33 drug delivery34 and biosensing.35 Similarly, the use of MSNs as stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems was proposed by prof. Lin using different agents to cap the pore entrances, such as quantium dots,28 gold nanoparticles,36 iron oxide nanoparticles37 or dendrimers.35 Regarding their application as drug delivery systems, MSNs provide a new therapeutic armamentarium able to address some of the most important limitations of conventional medicine, such as: lack of specificity, narrow window of efficacy, low drug solubility and/or stability, non-adequate pharmacokinetic profiles and potential side effects.38 In this sense, MSNs aim at transporting and releasing therapeutic compounds to diseased tissues in a selective and controlled manner.

Since MSNs were proposed as drug nanocarriers, there has been an increase in the publications about smart MSNs for the potential treatment of different diseases (Fig. 2).39 The reasons for such a success as nanovehicles could be found on their unique properties, such as: great textural characteristics to load a great amount of molecules, tuneable pore shape and pore diameter that allow loading a great variety of cargo molecules, robustness and easy functionalisation that allow engineering versatile different nanocarriers using the same platform, and, last but not least, their biocompatibility at therapeutic dosages.40

Figure 2.

Left: Number of publications on “Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles” + “Drug delivery” + “Responsive” in the last few years (source: Google Scholar). Top right corner: Transmission Electron Microscopy image of MSN. Bottom right corner: Schematic representation of the versatility of MSNs.

3.1. Trap therapeutic cargo

The high drug loading capacity of MSNs permits using fewer nanocarriers for the treatment of certain diseases than other nanoparticles, which could be relevant from a toxicity point of view. Additionally, the cargo molecules inside the mesopore system of the MSNs are protected from harsh environmental factors such as enzymatic degradation. Back in 2010, we showed, for the first time direct evidence of the drug confinement into the inner part of the pore channels through Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy with spherical aberration correctors incorporated (Fig. 3).41 Up to then, the presence of drugs into the pores was characterised through the sum of indirect techniques, such as nitrogen adsorption42 or thermogravimetry.43 The high resolution microscopy allowed the determination of the chemical composition of both matrix walls and pore area, which permitted the qualitative determination of the presence of molecules into the inner area of the mesopores. Thus, MSNs meet the first objective of any given nanomedicine: trapping and protecting a great amount of therapeutic cargo.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of drug loading into the pores of MSNs (top). [100] STEM image, perpendicular to the mesopores with the corresponding image intensity profile of Si and O layers (bottom left corner). [001] STEM image, parallel to the mesopores with the corresponding image intensity profile of C and N layers (bottom right corner).

3.2. Transport therapeutic cargo

Regarding the second objective of any nanomedicine – transporting the therapeutic cargo to a specific site avoiding premature leakage – MSNs exhibit an excellent performance not only for hosting and protecting the cargo, but also for transporting it to the site of the disease. It is relatively easy to graft targeting agents to the external surface of MSNs to direct them towards diseased tissues. The potential cargo leakage during the journey might be avoided capping the pore entrances with responsive gatekeepers, as commented bellow.

Most of the research on targeted delivery from MSNs has been dedicated to the fight against cancer. One of the reasons for that might be found in the fact that nanoparticles leak preferentially into tumour tissues when injected into the blood stream (passive targeting). They tend to accumulate in the tumour tissues thanks to their particular blood vessel architecture, in what is called Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR) effect, which improves the delivery of nanomedicines to tumours.44,45

However, the EPR effect offers less than a 2-fold increase in nanoparticle accumulation in comparison with normal organs, which might result in therapeutic concentrations that are not enough for treating some cancers.46 A possible alternative that has been widely explored consists in decorating the surface of the nanocarriers with ligands that present high affinity towards some specific membrane receptors overexpressed in tumour cells, in what is called active targeting (Fig. 4). This approach has improved the selectivity of nanomedicines towards tumour cells and tissues, although it is not available yet in the market.47

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of surface functionalisation and cargo loading on MSNs for targeted drug delivery.

3.3. Release therapeutic cargo

Finally, the third objective of any nanomedicine should be releasing high local concentrations of therapeutic agents on-demand.48 It is important to keep control on the cargo release to avoid the premature release of transported cargo before reaching the targeted tissues. If that might happen, there would be a drastic reduction of the nanomedicine efficiency and several side effects might occur if the transported cargo is cytotoxic. This is of particular interest on MSNs, where it is relatively easy to introduce cargo molecules inside the mesoporous system, but it is also relatively easy for those molecules to diffuse out. Thus, it is necessary to cap the pore entrances once the therapeutic cargo has been loaded. In this sense, MSNs present pores large enough to host many different therapeutic agents and yet small enough to be blocked by many different molecules working as pore caps. Those caps grafted at the pore entrances trap the loaded molecules avoiding their premature release, and only upon application of certain stimuli they might detach from the MSNs and trigger the cargo release. Recently, Zink and co-workers have categorised the different capping systems into three main groups: (1) Reusable caps, that work with a bulky capping molecule able to bind reversibly; (2) Completely reversible caps, that are based on the principle of reversal of affinity of a macromolecule with the shape of a ring twisted into a stem with two or more binding sites; and (3) Irreversible caps, that work through a chemical bond cleavage of the capping macromolecule, thus permanently separating from the host nanoparticle.49

The stimuli employed to trigger the release from MSNs can be external or internal. External stimuli are those that can be remotely applied by the clinician, so they are under control at all times by the operator, they can be turned on and off as required and they can be applied locally into the site of the disease. Many examples of MSNs externally triggered can be found in the literature, such as magnetic field,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62 light63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72 or ultrasound (US).73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81 On the other hand, internal stimuli are typical from the treated pathology. Among them, researchers on MSNs have employed pH (pH values of 6 or bellow can be found in tumours or lysosomes of cells),82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95 redox change potential (high concentration of antioxidants in the cytoplasm of tumour cells),28,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105 overexpression of certain enzymes by tumour cells,106,107,108,108,109,110,111,112,113,114 or specific antibodies to tumour cells.115,116 All this stimuli-responsive MSNs platforms have been reviewed extensively somewhere else.38,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129 This feature article will focus on the recent research carried out on ultrasound sensitive MSNs, one of the newest and most efficient stimuli employed with MSNs.

4. Ultrasound sensitive mesoporous silica nano-cariers

Although US has already been employed extensively in the clinic both for diagnostic and treatment,130,131 it is considered as one of the most promising triggers for drug delivery nanosystems.132 The reason for this interest relays on its capacity to non-invasively penetrate deep into the body without damaging healthy tissues.48

4.1. Ultrasound features

Ultrasound is commonly produced using piezoelectric transducers than can transform an electric signal to a mechanic wave that is able to travel across a fluid. In the biomedical area, US has been employed for tumour ablation,133 treatment of Alzheimer´s disease,134 hyperthermia generation,135 to cross the blood brain barrier,136 immunostimulation,136 biomedical imaging136 and physical therapy.137 US is classified in three categories: low (<1MHz), medium (1-5MHz) and high (5-10MHZ) frequency US. On one hand, low frequency ultrasound displays an exceptional penetration depth in living tissues and is non-invasive, although it cannot be focused into a specific spot. On the other hand, medium and high frequency US show inferior tissue penetration and might damage living tissue as a consequence of the heat produced by the increased scattering. However, they can be focused and, consequently, the intensity at the focal point is higher. In this sense, curved transducers are employed to focus high intensity US (High Intensity Focused Ultrasound, HIFU) inside the body, which make possible to employ it for destruction of internal tumour tissues from the outside.

When applying US to living tissues, there are two types of effects: thermal and mechanical effects.135 On one hand, thermal effects are produced as a consequence of the US travel across tissue, in which part the Energy can be adsorbed by the tissue itself. This hyperthermia phenomenon can be employed in ablative therapies against cancer. On the other hand, among mechanical effects, cavitation is the most employed ultrasonic phenomenon in biomedicine, and it is based on the formation and oscillation of gas bubbles in a fluid.138 The bubbles are formed when mechanical waves from US interact with fluids, and their radius can oscillate around an equilibrium for several acoustic cycles. When working at high pressures, at certain US frequency and bubble radius, the bubbles can grow unstable leading to a violent collapse during compression, in what is called inertial cavitation. This phenomenon can produce extreme conditions locally in terms of high temperature and high pressure at the nanoscale level, which lead to the emission of bursts of light (called sonoluminescence) and reactive oxygen species from the pyrolysis of water. This inertial cavitation, together with thermal and/or mechanical effects from US, can be employed to induce or accelerate chemical reactions, in what is known as sonochemistry.139

4.2. Ultrasound-responsive drug nano-carriers

The thermal,140 mechanical141 and chemical142 effects from US have been used for designing different US responsive drug delivery nano-carriers, such as liposomes,132,143,144,145 micelles142,146,147 and polymeric nanoparticles.148 This sudden interest from the drug release scientific community relays on the characteristics that ultrasound can offer to the field, such as high tissue penetration capacity, non-invasiveness, portability, economy and spatiotemporal control. Consequently, US has turned to be one of the most promising options for controlled drug delivery devices in biomedicine.149,150,151

4.3. Ultrasound-responsive MSNs

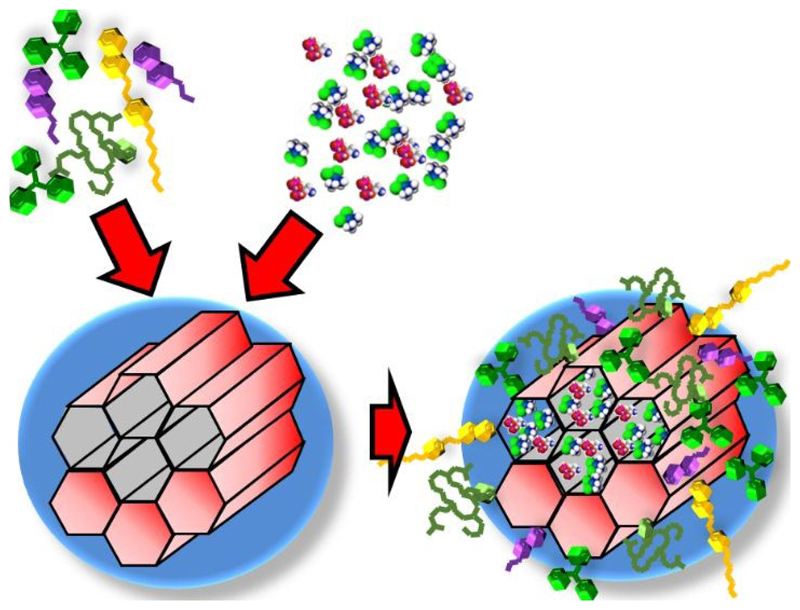

The first steps combining US with mesoporous silica were carried out using bulk mesoporous materials, such as MSM-41, whose pores were capped with poly(dimethylsiloxane). The application of US triggered the release of the previous loaded ibuprofen.152 It has been in the last few years, and motivated by the fast development of mesoporous silica nanoparticles,153 that US has been applied for triggering the release form MSNs (Fig. 5).154,155,156

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of US triggered release from MSNs.

Comparing US with other external stimuli such as light or magnetic field applied to MSNs, we can conclude that there is a delay in terms of research and publications on US-responsive MSNs. This fact can be associated to the difficulty of designing and developing US-responsive nanovalves at the pore entrances of MSNs.

4.3.1. US induced release from MSNs

We recently developed a type of US-sensitive MSNs capping the pore entrances with a specially designed co-polymer.73 Basically, the employed co-polymer presented a labile acetal group that could be cleaved through the application of US. Acetal removal resulted into a different polymer with different hydrophobicity. The transformation from hydrophobic to hydrophilic leaded to a change on the polymer conformation and triggered cargo release. One of the interesting features of our system is that one of the components provides thermo-responsive behaviour in a way that before US irradiation, the pores would be capped at 37°C and opened at 4°C. Thus, it might be possible to produce the nanocarriers with the co-polymer already grafted on the surface and then, in a separated step, the cargo can be loaded following a very simple procedure: place a MSNs solution into a fridge, add the drug solution and then place the loaded MSNs at 37°C, so the pore entrances would be capped with the cargo already loaded. This fact would allow producing the MSNs in a lab and then send them to a clinic where they could be easily loaded with the selected therapeutic agent and applied to the patient.

The designed US-responsive MSNs were checked not to be toxic in vitro. In this sense, none of the by-products from the nanocarriers before and after US irradiation affected the cell viability, ensuring their biocompatibility. Additionally, we checked the lack of damage into relevant biological molecules that might had been produced by the US exposure at 1MHz and 15W.73

The US-responsive behaviour after cellular internalisation was retained, as observed in an intracellular release experiment, loading the MSNs with a fluorophore. Furthermore, when the MSNs were loaded with doxorubicin (anticancer drug) and evaluated with prostate cancer cells (LNCaP), a lack of cellular toxicity was observed before the US application, which meant that the pores were appropriately blocked avoiding any premature release. However, there was a dose-dependent toxicity to prostate cancer cells when the MSNs were exposed to US (Fig. 6), demonstrating their capacity to kill cancer cells only under the application of US.

Figure 6.

Top: Fluorescence microscopy images of LNCaP prostate cancer cells with US-sensitive MSNs loaded with doxorubicin before US exposure (left) and after US exposure (right). Bottom: cell viability experiment in LNCaP cancer cells with different concentrations of doxorubicin loaded US-sensitive MSNs before US exposure (green) and after US exposure (red).

We then evaluated the opening mechanism of the US-sensitive MSNs in response to US, which theoretically could be due to thermal and/or mechanical effects. A new setting was developed, introducing a thermocouple in the sample holder to closely monitor the temperature and a passive cavitation detector to evaluate the mechanical acoustic cavitation. Three different frequencies (0.5, 1 and 3.3 MHz) of focused US were applied. We observed that applying certain intensity of inertial acoustic cavitation (mechanical effect) without significant temperature increase (thermal effect) was able to induce cargo release from MSNs. However, directly increasing the temperature of the sample or applying US with bulk heating but negligible cavitation were not capable of inducing cargo release. Thus, we were able to demonstrate that the mechanism to open the pore entrances of our US-sensitive MSNs was linked to acoustic cavitation, which ensures the safety of our system since the release will take place without increasing the temperature of the surrounding tissues.

In a different approach, US has been employed together with pH to develop a dual-responsive polydopamine-coated MSNs for controlled drug delivery.79 The polydopamine shell was grafted to the surface of the MSNs via self-polymerisation under alkaline conditions and the pores were loaded with doxorubicin. Upon high-intensity focused ultrasound exposure, the cargo was released via a pulsatile fashion because of the ultrasonic cavitation effect.

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles have also been loaded with paclitaxel and folic acid functionalised Beta-cyclodextrin has been employed to cap the pores and as cancer targeting agent.80 This nanocarrier enhanced the cavitation effect and achieved rapid drug release under low-energy ultrasound, which was evaluated both in vitro and in vivo.

A multidrug delivery vehicle was also developed with MSNs functionalised with folic acid and encapsulated into a microbubble.78 Cytotoxicity and cellular uptake experiments we confirmed in vitro and the antitumor efficacy was corroborated in tumour bearing mice.

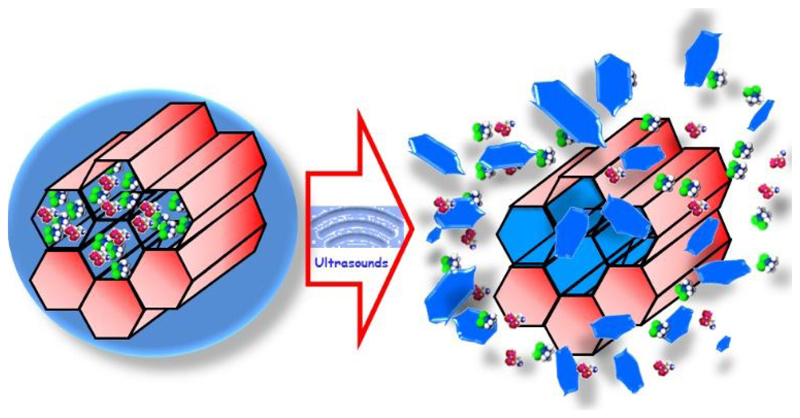

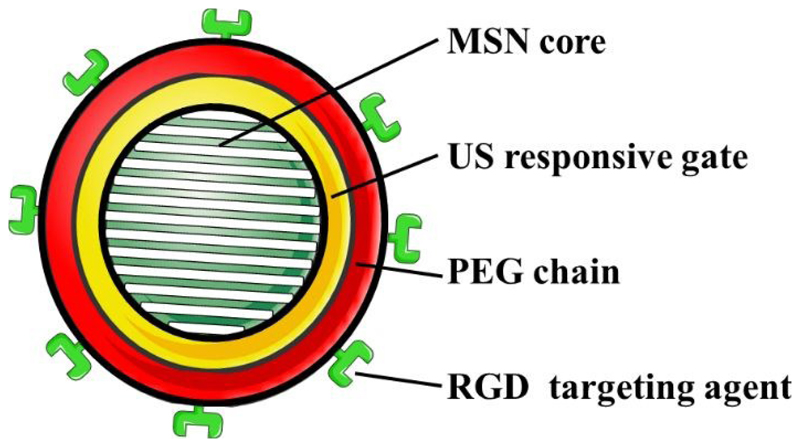

4.3.2. Targeting of US-responsive MSNs

One of the main objectives in nanomedicine for the potential treatment of cancer is the selective accumulation of the nanoparticles into the tumour areas without affecting healthy tissues. As it has been mentioned above, nanocarriers can be targeted and accumulated into tumours through either passive and/or active targeting. Both approaches are based on the circulation of the nanocarriers within the blood stream, so those nanoparticles must be stable in that physiological solution. In this sense, our previously developed US-sensitive MSNs presented a co-polymer on their surface that made them highly hydrophobic at physiological temperature which leaded to nanoparticle aggregation. Therefore, we covered those US-sensitive MSNs with a layer of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to prevent aggregation. Additionally, we grafted active targeting moieties through a series of chemical strategies to develop a PEGylated and modularly targeted US-responsive nanocarriers (Fig. 7).77 Those sets of chemical strategies had to be designed from scratch since previously reported methods were unable to produce this versatile US-responsive nanocarrier. Thus, we demonstrated that drug loaded RGD-targeted PEGylated US-responsive MSNs produced significantly increased cancer cell killing only when exposed to US.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the RGD-targeted PEGylated US-responsive MSNs produced.

Although MSNs might reach the targeted cancer tissue thanks to the EPR effect or the active targeting moiety, the treatment will not be completed until the cargo might be released into the cancer cells. Therefore, cells must uptake the nanoparticles and this might be enhanced by the presence of internalisation ligands (such as certain targeting agents) or positively charged moieties on the surface of the nanoparticles.157 This approach requires the development of hierarchical targeting strategies in which an internalisation ligand might be included in the formulation but hidden during the nanoparticles journey. In our lab, we developed this strategy using MSNs positively charged as the mechanism of internalisation, which was hidden by grafting PEG chains on the nanoparticle through a thermosensitive linker. Then, the application of US produced an increase of the temperature which provoked the disengage of the PEG chains from the nanoparticles and leaded to the exposure of the positive charges of the nanoparticles and, therefore, favouring the cellular uptake.76

Unfortunately, the presence of targeting agents on the surface of the nanoparticles to specific cancer cell receptors can lead to what is called the binding site barrier. The first line of cancer cells from a tumour will interact with the targeted nanoparticles in a very strong manner, leading to the retention of those nanoparticles in peripheral areas of the tumour mass and impeding their penetration to deeper areas of the tumour.158 Additionally, large solid tumours normally present an elevated interstitial pressure, which limits the nanoparticle penetration deep into the tumour.159 A possible way to ensure the penetration of the MSNs into the mass might be through the use of ultrasound-induced inertial cavitation, which has been demonstrated to enhance the penetration into an agarose tissue model.75 Additionally, the combination of MSNs with submicrometric cavitation nuclei was observed to be more efficient way of nanoparticle penetration, which could be of interest in future applications of extravasation or tumour mass penetration of MSNs.

5. Cellular vehicles for MSNs

Although the above mentioned approaches for targeting nanoparticles might had worked in the past with certain types of nanocarriers,160 the expected results in NPs targeting have not been achieved.161,162 That was the motivation to explore different alternatives to localise MSNs into tumours. One of those alternatives was based on using cells that migrate towards tumours to transport different nanoparticles to those tissues.163 Certain mesenchymal stem cells present inherent migratory properties in response to inflammation or injury, so they can be employed as cellular vehicles.164,165 Bone marrow and adipose tissue are the most common source of adult mesenchymal stem cells, but they present some drawbacks, such as highly invasive methods for extraction and inefficient isolation techniques. We have been working with an additional type of adult mesenchymal stem cells from the human placenta, decidua mesenchymal stem cells (DMSCs), that present some advantages, such as non-invasive and straightforward isolation techniques, low or non-immune response migratory properties towards tumours.166,167 We took advantage of those properties to transport our US-responsive MSNs to tumour tissues, aiming the controlled release of the cytotoxic cargo only at the tumour environment.74 Our initial approach consisted on exploring the internalisation of MSNs into DMSCs, evaluating their potential toxicity and the retention time inside the cells.168 We found that MSNs with positive surface charge were better internalised than regular MSNs thanks to the electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged cell membrane (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Fluorescence images of DMSCs with MSNs loaded: blue (nucleus), red (cytoplasm) and green (MSNs). (a) green channel, (b) green and blue channels, (c) green, blue and red channels.

Thus, the US-responsive MSNs were coated with poly(ethyleneimine) to favour their internalisation into the DMSCs. The US responsiveness of the nanocarriers was confirmed after the internalisation both in vitro and in vivo, as expected. The migration capacity towards tumours of the DMSCs loaded with the US-responsive MSNs was confirmed in an in vitro cell migration essay. Thus, we demonstrated that those cells can transport the loaded nanoparticles to a tumour tissue and, once in the these, the release of the cytotoxic cargo can be triggered with US affecting only at the cells present on the tumour environment.74

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In summary, the outstanding properties of MSNs, such as high loading capacity, controllable particle size and shape, suitability for easy surface modification and biocompatibility, make them ideal candidates for drug delivery nanocarriers. In this feature article we have shown that using ultrasound for the spatio-temporal controlled administration of potent drugs is a promising alternative for treating tumours. The administration of the transported drugs can be remotely triggered by the clinician, and the administered dose can be controlled with extremely high precision. It is this combination of selectivity and control in the release in a single nanocarrier, what provides a powerful tool in the fight against complex diseases such as cancer.

The future perspectives on the use of US with MSNs for biomedical applications are somehow linked to the ultrasound benefits and limitations. Among the former, the combination of portability, low cost and ease of use make US an affordable stimulus. Additionally, US combines a unique ability for soft tissue penetration without damaging it and very good spatial resolution, which can attain a spatial focus on the order of 10 mm3. Those characteristics have made US the most widely used imaging technique in modern medicine. We have shown in this Feature Article that the technical issues of applying the US technology to MSNs can be solved, and it actually works. However, US present an important drawback when used in biomedicine: the blockage by bone and air. This means that this technology might be reduced to soft tissues areas, limiting its application in the clinic for drug delivery purposes.

From a more general perspective, and even though there has been a great progress in the design and development of MSNs for various biomedical applications, clinical translation has not been achieved yet. From our perspective, there are several challenges that should be solved before advancing to clinical trials, such as: the need for standardising the production methods to achieve reproducibility in the synthesis of mesoporous silica nanoparticles, good stability and dispersibility, or surface functionalisation protocols for clinical applications. Additionally, more biodistribution studies of MSNs should be carried out trying to reduce the variation in experimental design criteria for obtaining consistent results. In this sense, a recent perspective article written by World leaders in the nanomedicine area tries to stablish the fundamentals for understanding the bio-nano-interface in nanoparticles.169 The authors state that to overtake the experimental variability in nanomedicine research there should be a “minimum information standard” divided in three categories: (1) materials characterisation, (2) biological characterisation, and (3) details of experimental protocols. Thus, reproducibility could be improved and comparisons and meta analyses could be easily carried out. This would improve the level of communication between researchers in the field favouring the knowledge outcome from different in vivo experiments and, sooner than later, achieve the desired translation to the clinic.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council, ERC-2015 AdG (VERDI), Proposal No. 694160, and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO), MAT1015-64831-R grant.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Ragelle H, Danhier F, Préat V, Langer R, Anderson DG. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14:851–864. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2016.1244187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Nat Biotechnol. 2015:33. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips E, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Carvajal RD, Mohan P, Ye Y, Humm J, Gönen M, Kalaigian H, Schöder H, Strauss HW, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:260ra149 LP–260ra149. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanagisawa T, Shimizu T, Kuroda K, Kato C. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1990;63:988–992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kresge CT, Leonowicz ME, Roth WJ, Vartuli JC, Beck JS. Nature. 1992;359:710. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck JS, Vartuli JC, Roth WJ, Leonowicz ME, Kresge CT, Schmitt KD, Chu CTW, Olson DH, Sheppard EW, McCullen SB, Higgins JB, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10834–10843. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huo Q, Margolese DI, Ciesla U, Demuth DG, Feng P, Gier TE, Sieger P, Firouzi A, Chmelka BF. Chem Mater. 1994;6:1176–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu PS, Chen GF. In: Liu PS, Chen GFBT-PM, editors. Butterworth-Heinemann; Boston: 2014. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pal N, Bhaumik A. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;189–190:21–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farjadian F, Roointan A, Mohammadi-Samani S, Hosseini M. Chem Eng J. 2019;359:684–705. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huh S, Wiench JW, Yoo J-C, Pruski M, Lin VS-Y. Chem Mater. 2003;15:4247–4256. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann F, Cornelius M, Morell J, Fröba M. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2006;45:3216–3251. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallet-Regi M, Rámila A, Del Real RP, Pérez-Pariente J. Chem Mater. 2001;13:308–311. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang P, Gai S, Lin J. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3679–3698. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15308d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. Prog Solid State Chem. 2012;40:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Giri S, Lin VS-Y. Adv Funct Mater. 2007;17:1225–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:5593. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balas F, Manzano M, Horcajada P, Vallet-Regi M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8116–8117. doi: 10.1021/ja062286z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina-Manso D, Manzano M, Doadrio JC, Del Prado G, Ortiz-Pérez A, Vallet-Regí M, Gómez-Barrena E, Esteban J. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:252–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colilla M, Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3:403–414. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen F, Hong H, Zhang Y, Valdovinos HF, Shi S, Kwon GS, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W. ACS Nano. 2013;7:9027–9039. doi: 10.1021/nn403617j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He L, Huang Y, Zhu H, Pang G, Zheng W, Wong Y-S, Chen T. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:2754–2763. [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Torre C, Domínguez-Berrocal L, Murguía JR, Marcos MD, Martínez-Máñez R, Bravo J, Sancenón F. Chem – A Eur J. 2018;24:1890–1897. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu S-H, Mou C-Y, Lin H-P. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:3862–3875. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai Q, Luo Z-S, Pang W-Q, Fan Y-W, Chen X-H, Cui F-Z. Chem Mater. 2001;13:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler CE, Khushalani D, Lebeau B, Mann S. Adv Mater. 2001;13:649–652. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nooney RI, Thirunavukkarasu D, Chen Y, Josephs R, Ostafin AE. Chem Mater. 2002;14:4721–4728. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai C-Y, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, Jeftinija K, Xu S, Jeftinija S, Lin VS-Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao F, Botella P, Corma A, Blesa J, Dong L. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:1796–1804. doi: 10.1021/jp807956r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou Z, Theyssen N, Brinkmann A, V Klementiev K, Grünert W, Bühl M, Schmidt W, Spliethoff B, Tesche B, Weidenthaler C, Leitner W. J Catal. 2008;258:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martines MU, Yeong E, Persin M, Larbot A, Voorhout WF, Kübel CKU, Kooyman P, Prouzet E. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2005;8:627–634. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y-S, Tsai C-P, Huang H-Y, Kuo C-T, Hung Y, Huang D-M, Chen Y-C, Mou C-Y. Chem Mater. 2005;17:4570–4573. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenholm JM, Meinander A, Peuhu E, Niemi R, Eriksson JE, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. ACS Nano. 2009;3:197–206. doi: 10.1021/nn800781r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu J, Liong M, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Small. 2007;3:1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radu DR, Lai C-Y, Wiench JW, Pruski M, Lin VS-Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1640–1641. doi: 10.1021/ja038222v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torney F, Trewyn BG, Lin VS-Y, Wang K. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:295. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giri S, Trewyn BG, Stellmaker MP, Lin VS-Y. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2005;44:5038–5044. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vallet-Regí M, Colilla M, Izquierdo-Barba I, Manzano M. Molecules. 2018;23:47. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallet-Regí M, Tamanoi F. In: Mesoporous Silica-based Nanomaterials and Biomedical Applications, Part A. Tamanoi FBT-TE, editor. Vol. 43. Academic Press; 2018. pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu J, Liong M, Li Z, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Small. 2010;6:1794–1805. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallet-Regí M, Manzano M, González-Calbet JM, Okunishi E. Chem Commun. 2010;46:2956–8. doi: 10.1039/c000806k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallet-Regi M, Balas F, Colilla M, Manzano M. Drug Metab Lett. 2007;1:37–40. doi: 10.2174/187231207779814382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lehto V-P, Vähä-Heikkilä K, Paski J, Salonen J. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2005;80:393–397. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387 LP–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maeda H, Nakamura H, Fang J. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura Y, Mochida A, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27:2225–2238. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:759 LP–768. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Nat Mater. 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar N, Chen W, Cheng C-A, Deng T, Wang R, Zink JI. In: Mesoporous Silica-based Nanomaterials and Biomedical Applications, Part A. Tamanoi FBT-TE, editor. Vol. 43. Academic Press; 2018. pp. 31–65. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arcos D, Fal-Miyar V, Ruiz-Hernández E, Garcia-Hernández M, Ruiz-González ML, González-Calbet J, Vallet-Regí M. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas CR, Ferris DP, Lee J-H, Choi E, Cho MH, Kim ES, Stoddart JF, Shin J-S, Cheon J, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10623–10625. doi: 10.1021/ja1022267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saint-Cricq P, Deshayes S, Zink JI, Kasko AM. Nanoscale. 2015;7:13168–13172. doi: 10.1039/c5nr03777h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rühle B, Datz S, Argyo C, Bein T, Zink JI. Chem Commun. 2016;52:1843–1846. doi: 10.1039/c5cc08636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruiz-Hernández E, Baeza A, Vallet-Regí M. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1259–66. doi: 10.1021/nn1029229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Y, Tao C. RSC Adv. 2015;5:22365–22372. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baeza A, Guisasola E, Ruiz-Hernández E, Vallet-Regí M. Chem Mater. 2012;24:517–524. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guisasola E, Asín L, Beola L, de la Fuente JM, Baeza A, Vallet-Regí M. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:12518–12525. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b02398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guisasola E, Baeza A, Talelli M, Arcos D, Moros M, De La Fuente JM, Vallet-Regí M. Langmuir. 2015;31:12777–12782. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guisasola E, Baeza A, Talelli M, Arcos D, Vallet-Regí M. RSC Adv. 2016;6:42510–42516. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bringas E, Köysüren Ö, Quach DV, Mahmoudi M, Aznar E, Roehling JD, Marcos MD, Martínez-Máñez R, Stroeve P. Chem Commun. 2012;48:5647–5649. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31563g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang B, Guo J, Liu C, Qian J, Yang W. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:9941–9947. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen P-J, Hu S-H, Hsiao C-S, Chen Y-Y, Liu D-M, Chen S-Y. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:2535–2543. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sierocki P, Maas H, Dragut P, Richardt G, Vögtle F, De Cola L, Brouwer F, Zink JI. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24390–24398. doi: 10.1021/jp0641334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu Y, Fujiwara M. Angew Chemie-International Ed. 2007;46:2241–2244. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu J, Choi E, Tamanoi F, Zink JI. Small. 2008;4:421–426. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferris DP, Zhao Y-L, Khashab NM, Khatib HA, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1686–1688. doi: 10.1021/ja807798g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarn D, Ferris DP, Barnes JC, Ambrogio MW, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Nanoscale. 2014;6:3335–3343. doi: 10.1039/c3nr06049g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang D, Wu S. Langmuir. 2016;32:632–636. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b04399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agostini A, Sancenón F, Martínez-Máñez R, Marcos MD, Soto J, Amorós P. Chem – A Eur J. 2012;18:12218–12221. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lai J, Mu X, Xu Y, Wu X, Wu C, Li C, Chen J, Zhao Y. Chem Commun. 2010;46:7370–7372. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02914a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Z, Wang L, Wang J, Jiang X, Li X, Hu Z, Ji Y, Wu X, Chen C. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1418–1423. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martínez-Carmona M, Lozano D, Baeza A, Colilla M, Vallet-Regí M. Nanoscale. 2017;9:15967–15973. doi: 10.1039/c7nr05050j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paris JL, Cabanas MV, Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. ACS Nano. 2015;9:11023–11033. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paris JL, De La Torre P, Cabañas MV, Manzano M, Grau M, Flores AI, Vallet-Regí M. Nanoscale. 2017;9:5528–5537. doi: 10.1039/c7nr01070b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paris JL, Mannaris C, Cabañas MV, Carlisle R, Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M, Coussios CC. Chem Eng J. 2018;340:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paris JL, Manzano M, Cabañas V, Vallet-Regi M. Nanoscale. 2018;10:6402–6408. doi: 10.1039/C8NR00693H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paris JL, Villaverde G, Cabañas MV, Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6:2785–2794. doi: 10.1039/c8tb00444g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lv Y, Cao Y, Li P, Liu J, Chen H, Hu W, Zhang L. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700354. 1700354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li X, Xie C, Xia H, Wang Z. Langmuir. 2018;34:9974–9981. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b01091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang J, Jiao Y, Shao Y. Mater (Basel, Switzerland) 2018;11:2041. doi: 10.3390/ma11102041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X, Chen H, Zheng Y, Ma M, Chen Y, Zhang K, Zeng D, Shi J. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2057–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, Zhao Y-L, Tamanoi F, Stoddart JF, Zink JI, Nel AE. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12690–12697. doi: 10.1021/ja104501a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Z, Clemens DL, Lee B-Y, Dillon BJ, Horwitz MA, Zink JI. ACS Nano. 2015;9:10778–10789. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Angelos S, Khashab NM, Yang Y-W, Trabolsi A, Khatib HA, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12912–12914. doi: 10.1021/ja9010157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Théron C, Gallud A, Carcel C, Gary-Bobo M, Maynadier M, Garcia M, Lu J, Tamanoi F, Zink JI, Wong Chi Man M. Chem – A Eur J. 2014;20:9372–9380. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhao Y-L, Li Z, Kabehie S, Botros YY, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13016–13025. doi: 10.1021/ja105371u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Acosta C, Pérez-Esteve E, Fuenmayor CA, Benedetti S, Cosio MS, Soto J, Sancenón F, Mannino S, Barat J, Marcos MD, Martínez-Máñez R. ACS Appl Interfaces Mater. 2014;6:6453–6460. doi: 10.1021/am405939y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cauda V, Argyo C, Schlossbauer A, Bein T. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:4305–4311. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xing L, Zheng H, Cao Y, Che S. Adv Mater. 2012;24:6433–6437. doi: 10.1002/adma.201201742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fu J, Zhu Y, Zhao Y. J Mater B Chem. 2014;2:3538–3548. doi: 10.1039/c4tb00387j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenholm JM, Peuhu E, Eriksson JE, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3308–3311. doi: 10.1021/nl901589y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Y, Shi J, Shen W, Dong X, Feng J, Ruan M, Li Y. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2005;44:5083–5087. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martínez-Carmona M, Lozano D, Colilla M, Vallet-Regí M. Acta Biomater. 2018;65:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gisbert-Garzarán M, Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. Bioengineering. 2017;4:3. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering4010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gisbert-Garzaran M, Lozano D, Vallet-Regí M, Manzano M. RSC Adv. 2017;7:132–136. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nguyen TD, Tseng H-R, Celestre PC, Flood AH, Liu Y, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10029 LP–10034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504109102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nguyen TD, Liu Y, Saha S, Leung KC-F, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:626–634. doi: 10.1021/ja065485r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ambrogio MW, Pecorelli TA, Patel K, Khashab NM, Trabolsi A, Khatib HA, Botros YY, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. Org Lett. 2010;12:3304–3307. doi: 10.1021/ol101286a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ma X, Nguyen KT, Borah P, Ang CY, Zhao Y. Adv Healthc Mater. 2012;1:690–697. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang J, Niemelä M, Westermarck J, Rosenholm JM. Dalt Trans. 2014;43:4115–4126. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53071j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Porta F, Lamers GEM, Zink JI, Kros A. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:9982–9985. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02959a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Khashab NM, Trabolsi A, Lau YA, Ambrogio MW, Friedman DC, Khatib HA, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. European J Org Chem. 2009;2009:1669–1673. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nadrah P, Porta F, Planinšek O, Kros A, Gaberšček M. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15:10740–10748. doi: 10.1039/c3cp44614j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee B-Y, Li Z, Clemens DL, Dillon BJ, Hwang AA, Zink JI, Horwitz MA. Small. 2016;12:3690–3702. doi: 10.1002/smll.201600892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shi P, Qu Y, Liu C, Khan H, Sun P, Zhang W. ACS Macro Lett. 2016;5:88–93. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Patel K, Angelos S, Dichtel WR, Coskun A, Yang Y-W, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2382–2383. doi: 10.1021/ja0772086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Park C, Kim H, Kim S, Kim C. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16614–16615. doi: 10.1021/ja9061085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Singh N, Karambelkar A, Gu L, Lin K, Miller JS, Chen CS, Sailor MJ, Bhatia SN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19582–19585. doi: 10.1021/ja206998x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mondragón L, Mas N, Ferragud V, de la Torre C, Agostini A, Martínez-Máñez R, Sancenón F, Amorós P, Pérez-Payá E, Orzáez M. Chem – A Eur J. 2014;20:5271–5281. doi: 10.1002/chem.201400148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baeza A, Guisasola E, Torres-Pardo A, González-Calbet JM, Melen GJ, Ramirez M, Vallet-Regí M. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:4625–4633. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Radhakrishnan K, Gupta S, Gnanadhas DP, Ramamurthy PC, Chakravortty D, Raichur AM. Part Part Syst Charact. 2013;31:449–458. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cheng Y-J, Luo G-F, Zhu J-Y, Xu X-D, Zeng X, Cheng D-B, Li Y-M, Wu Y, Zhang X-Z, Zhuo R-X, He F. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:9078–9087. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b00752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.van Rijt SH, Bölükbas DA, Argyo C, Datz S, Lindner M, Eickelberg O, Königshoff M, Bein T, Meiners S. ACS Nano. 2015;9:2377–2389. doi: 10.1021/nn5070343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kumar B, Kulanthaivel S, Mondal A, Mishra S, Banerjee B, Bhaumik A, Banerjee I, Giri S. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2017;150:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ruehle B, Clemens DL, Lee B-Y, Horwitz MA, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:6663–6668. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bhat R, García I, Aznar E, Arnaiz B, Martínez-Bisbal MC, Liz-Marzán LM, Penadés S, Martínez-Máñez R. Nanoscale. 2018;10:239–249. doi: 10.1039/c7nr06415b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Manzano M, Colilla M, Vallet-Regí M. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:1383–1400. doi: 10.1517/17425240903304024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ambrogio MW, Thomas CR, Zhao Y-L, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:903–913. doi: 10.1021/ar200018x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee JE, Lee N, Kim T, Kim J, Hyeon T. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:893–902. doi: 10.1021/ar2000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2590–2605. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Vivero-Escoto JL, Huxford-Phillips RC, Lin W. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2673–2685. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15229k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chen Y, Chen H, Shi J. Adv Mater. 2013;25:3144–3176. doi: 10.1002/adma.201205292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Argyo C, Weiss V, Bräuchle C, Bein T. Chem Mater. 2014;26:435–451. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tao Z. RSC Adv. 2014;4:18961–18980. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Biju V. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:744–764. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60273g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Peng F, Su Y, Zhong Y, Fan C, Lee S-T, He Y. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:612–623. doi: 10.1021/ar400221g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rühle B, Saint-Cricq P, Zink JI. ChemPhysChem. 2016;17:1769–1779. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201501167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Aznar E, Oroval M, Pascual L, Murguía JR, Martínez-Máñez R, Sancenón F. Chem Rev. 2016;116:561–718. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Baeza A, Manzano M, Colilla M, Vallet-Regí M. Biomater Sci. 2016;4:803–813. doi: 10.1039/c6bm00039h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wood AKW, Sehgal CM. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:905–928. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mitragotri S. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:255. doi: 10.1038/nrd1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rwei AY, Paris JL, Wang B, Wang W, Axon CD, Vallet-Regí M, Langer R, Kohane DS. Nat Biomed Eng. 2017;1:644–653. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kennedy JE. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:321. doi: 10.1038/nrc1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Burgess A, Dubey S, Yeung S, Hough O, Eterman N, Aubert I, Hynynen K. Radiology. 2014;273:736–745. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.van den Bijgaart RJE, Eikelenboom DC, Hoogenboom M, Fütterer JJ, den Brok MH, Adema GJ. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:247–258. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1891-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hynynen K, McDannold N, Sheikov NA, Jolesz FA, Vykhodtseva N. Neuroimage. 2005;24:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.D D, C J, C D. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 1995;22:142–150. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.22.4.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Arvanitis CD, Bazan-Peregrino M, Rifai B, Seymour LW, Coussios CC. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:1838–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cintas P, Tagliapietra S, Caporaso M, Tabasso S, Cravotto G. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015;25:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ernsting MJ, Worthington A, May JP, Tagami T, Kolios MC, Li S. 2011 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium; 2011. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Geers B, Lentacker I, Sanders NN, Demeester J, Meairs S, De Smedt SC. J Control Release. 2011;152:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wang J, Pelletier M, Zhang H, Xia H, Zhao Y. Langmuir. 2009;25:13201–13205. doi: 10.1021/la9018794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Schroeder A, Kost J, Barenholz Y. Chem Phys Lipids. 2009;162:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Grüll H, Langereis S. J Control Release. 2012;161:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Schroeder A, Honen R, Turjeman K, Gabizon A, Kost J, Barenholz Y. J Control Release. 2009;137:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Li F, Xie C, Cheng Z, Xia H. Ultrason Sonochem. 2016;30:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Xuan J, Boissière O, Zhao Y, Yan B, Tremblay L, Lacelle S, Xia H, Zhao Y. Langmuir. 2012;28:16463–16468. doi: 10.1021/la303946b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Papa A-L, Korin N, Kanapathipillai M, Mammoto A, Mammoto T, Jiang A, Mannix R, Uzun O, Johnson C, Bhatta D, Cuneo G, Ingber DE. Biomaterials. 2017;139:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sirsi SR, Borden MA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;72:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Elhelf IAS, Albahar H, Shah U, Oto A, Cressman E, Almekkawy M. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2018;99:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yang Z, Xiaoxia H, Xiangxiang J, Yu C. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6 1700646. [Google Scholar]

- 152.K H-J, M H, Z H, H I. Adv Mater. 2006;18:3083–3088. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Manzano M, Vallet-Regí M. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2018;29 doi: 10.1007/s10856-018-6069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lee S-F, Zhu X-M, Wang Y-XJ, Xuan S-H, You Q, Chan W-H, Wong C-H, Wang F, Yu JC, Cheng CHK, Leung KC-F. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:1566–1574. doi: 10.1021/am4004705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Milgroom A, Intrator M, Madhavan K, Mazzaro L, Shandas R, Liu B, Park D. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2014;116:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ming M, Huixiong X, Hangrong C, Xiaoqing J, Kun Z, Qi W, Shuguang Z, Rong W, Minghua Y, Xiaojun C, Faqi L, Jianlin S. Adv Mater. 2014;26:7378–7385. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Wang S, Huang P, Chen X. Adv Mater. 2016;28:7340–7364. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Chauhan VP, Jain RK. Nat Mater. 2013;12:958. doi: 10.1038/nmat3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Nichols JW, Bae YH. J Control Release. 2014;190:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Barenholz Y. J Control Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Venditto VJ, Szoka FC. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Wilhelm S, Tavares AJ, Dai Q, Ohta S, Audet J, Dvorak HF, Chan WCW. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1 [Google Scholar]

- 163.Gao Z, Zhang L, Hu J, Sun Y. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol Med. 2013;9:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hu Y-L, Fu Y-H, Tabata Y, Gao J-Q. J Control Release. 2010;147:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Macias MI, Grande J, Moreno A, Domínguez I, Bornstein R, Flores AI. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:495.e9–495.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Vegh I, Grau M, Gracia M, Grande J, de la Torre P, Flores AI. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;20:8. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2012.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Paris JL, La Torre PD, Manzano M, Cabañas MV, Flores AI, Vallet-Regí M. Acta Biomater. 2016;33:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Faria M, Björnmalm M, Thurecht KJ, Kent SJ, Parton RG, Kavallaris M, Johnston APR, Gooding JJ, Corrie SR, Boyd BJ, Thordarson P, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2018;13:777–785. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]