Abstract

Background/Aims

Inhibition of α4β7 integrin has been shown to be effective for induction and maintenance therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). We investigated the effects of varying doses of the α4β7 inhibitor abrilumab in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe UC despite conventional treatments.

Methods

In this randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled study, 45 UC patients were randomized to abrilumab 21 mg (n=11), 70 mg (n=12), 210 mg (n=9), or placebo (n=13) via subcutaneous (SC) injection for 12 weeks. The double-blind period was followed by a 36-week open-label period, in which all patients received abrilumab 210 mg SC every 12 weeks, and a 28-week safety follow-up period. The primary efficacy variable was clinical remission at week 8 (total Mayo score ≤2 points with no individual subscore >1 point).

Results

Clinical remission at week 8 was 4 out of 31 (12.9%) overall in the abrilumab groups versus 0 out of 13 in the placebo group (abrilumab 21 mg, 1/10 [10.0%]; 70 mg, 2/12 [16.7%]; 210 mg, 1/9 [11.1%]). In both the double-blind and open-label periods, fewer patients in the abrilumab groups experienced ≥1 adverse event compared with those in the placebo group. There were no cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and no deaths.

Conclusions

Abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg yielded numerically better results in terms of clinical remission rate at Week 8 than placebo, with the 210 mg dose showing more consistent treatment effects. Abrilumab was well tolerated in Japanese patients with UC.

Keywords: Colitis, ulcerative; Japan; AMG 181; Abrilumab

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a diffuse non-specific inflammation in the colon of unknown etiology, which primarily damages the mucosa and often causes erosion or ulceration [1]. Some patients experience spontaneous remission while others have frequent flare-ups. UC can develop at any age, but it is most prevalent in people aged 30 to 40 years. Its incidence is highest in late adolescence and early adulthood [2]. It appears to occur at a slightly later age in Asian patients [3].

The number of UC patients in Japan is rapidly increasing, with more than 117,000 patients with UC registered in 2010 [4]. It is reported that 65%, 30%, and 5% of Japanese UC patients are diagnosed with mild, moderate, and severe disease, respectively, at their first diagnosis [5].

While milder disease at first diagnosis can predict a more favorable clinical course [5], the accumulated 10-year recurrence rate ranges from approximately 70% to almost 100%, and the disease tends to recur repeatedly in patients whose disease first recurs within 1 year from onset [6]. The cumulative surgery rate 10 years from disease onset is 15%, and the surgery rate may be as high as 40% for pancolitis, where the lesion extends over the entire colon [7].

Global guidelines for the treatment of UC generally recommend corticosteroids for induction of remission in patients with moderate-to-severe active UC. For patients who experience a severe flare-up of disease requiring corticosteroid treatment or require re-treatment during the year with another course of corticosteroids, therapy with azathioprine (AZA) or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), preferably substituted as maintenance therapy, should be considered to avoid long-term corticosteroid use [8,9]. AZA, 6-MP, or infliximab are also recommended to treat flare-ups, while infliximab and adalimumab have shown effectiveness in severe or refractory UC [8-11].

Treatment options for moderate-to-severe UC in Japan are limited. Treatment of UC in Japan is similar to that in other countries, with corticosteroid therapy used as the basis of treatment for moderate or worse cases, despite its inability to provide sustained remission [1].

Abrilumab is a fully human monoclonal IgG2 directed against the human α4β7 integrin heterodimer. It specifically binds α4β7 with high affinity and inhibits α4β7, blocking its interaction with mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1. Mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 is selectively expressed in gut endothelium and is upregulated in patients with IBD [12,13].

Specific inhibition of lymphocyte homing to the gut has been shown to provide effective treatment of IBD [14]. Preclinical studies of α4β7 blockade [15,16] and clinical data from studies of vedolizumab [14] and abrilumab [17] have shown that blocking α4β7 integrin on the surface of gut homing lymphocytes significantly improves UC signs and symptoms, and may induce remission in patients with UC. Safety results for abrilumab are also available from healthy subjects and from patients with UC, and no dose-limiting toxicities or identified risks, including progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), have been identified [17].

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the efficacy, safety (including anti-drug antibodies to abrilumab), and tolerability of abrilumab 21 mg, 70 mg, and 210 mg in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe UC despite treatment with conventional therapies. The study also examined the pharmacokinetics (PK), receptor occupancy, and pharmacodynamic (PD) effect of abrilumab. We expected that abrilumab would show better efficacy in inducing remission compared with placebo at week 8.

METHODS

1. Ethics

The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation/Good Clinical Practice, Good Clinical Practice for Trials on Drugs (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ordinance No. 28, 27 March 1997), and the AstraZeneca K.K. policy on Bioethics and Human Biological Samples. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each investigational site, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation (or their legal guardians if aged under 20 years). This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01959165).

2. Overall Study Design

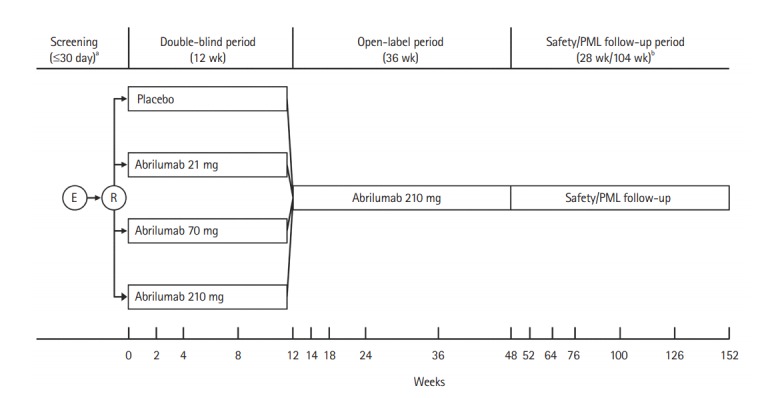

This was a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled, parallel group, phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of multiple doses of 21 mg and 70 mg abrilumab, and a single dose of 210 mg of abrilumab in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe UC. The study was conducted from 21 November 2013 to 15 October 2016. The study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design. aScreening could be performed up to 3 times; patients who did not complete the initial screening or did not meet the eligibility criteria at the initial screening were permitted to be screened again up to 2 times; bFor patients who discontinued the study drug, the 28-week safety follow-up and the 104-week progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) follow-up were carried out after the last dose of the study drug. E, enrolment; R, randomization.

The study consisted of 3 study periods. In the 12-week double-blind period, the patients were randomized using an interactive web response system to receive placebo or multiple doses of 21 mg or 70 mg, or a single dose of 210 mg of abrilumab in a ratio of 1:1:1:1.

In the placebo and abrilumab 21 mg and 70 mg groups, patients received the investigational product by subcutaneous (SC) injection on day 1, and at weeks 2, 4, and 8. In the abrilumab 210 mg group, patients received abrilumab 210 mg SC on day 1 and placebo at weeks 2, 4, and 8. Patients were stratified according to prior anti-TNF-α agent use and participation in an immunophenotyping and absolute counting PD assay sub-study, with 40% to 60% of patients with any prior anti-TNF agent use permitted in the study.

Randomization codes were allocated strictly and sequentially as patients became eligible. After randomization, an unblinded pharmacist or designee in each site prepared the investigational products according to a preparation manual and provided them to blinded site staff under blinded conditions.

All documents/information indicating patients’ treatment details were handled confidentially. The double-blind period was followed by a 36-week open-label period in which all patients received abrilumab 210 mg SC every 12 weeks, and then a 28-week safety/104-week PML follow-up period.

A randomized, double-blind design was selected to minimize bias. Placebo was selected as the control drug to evaluate the efficacy of abrilumab precisely, but concomitant use of 5-aminosalicylic acid, oral prednisolone (or equivalent), and AZA or 6-MP (or equivalent) was permitted in the double-blind period on the condition that the dosage and administration remained unchanged during the period. The open-label period was established to evaluate the efficacy in persistent response and the long-term safety of abrilumab, and to provide patients with continued treatment opportunity from an ethical point of view. The 28-week safety follow-up period was established to evaluate late adverse events (AEs), and its duration was determined as ≥ 5 times the elimination half-life of abrilumab 210 mg from a global phase I Study 20101261 (33.8 ± 6.74 days) (data on file). The PML follow-up period was established as in the overseas phase II study [17]. The dose of abrilumab for the Japanese patients in this study was based on previous study 20110259 (data on file), which showed that the PK and PD of abrilumab were similar in Japanese and non-Japanese patients, meaning no dose adjustments were required.

3. Patients

The inclusion criteria were: age 18 to 65 years at screening; a diagnosis of UC established ≥3 months before visit 2 (week 0); moderate-to-severe active UC (total Mayo score of 6 to 12 with a rectosigmoidoscopy score ≥2 measured in the screening period) prior to visit 2; and inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance to immunomodulators and/or anti-TNF-α agents. Patients taking AZA or 6-MP could be included if the treatment had been initiated ≥12 weeks prior to visit 2 and the dosage had been stable for ≥ 8 weeks prior to visit 2, or if the treatment had been discontinued ≥8 weeks before visit 2. Similarly, patients taking 5-aminosalicylic acid and/or oral prednisone or equivalent up to 20 mg/day were included if the dosage had been stable for ≥2 weeks prior to visit 2. Patients also required to have normal neurological examination findings, no history of tuberculosis, and a negative tuberculosis test at screening to be included.

The exclusion criteria were rectal disease only (i.e., within 10 cm of the anal verge); toxic megacolon; CD; history of subtotal colectomy with ileorectostomy or colectomy with ileoanal pouch, Koch pouch, or ileostomy for UC; planned bowel surgery within 12 weeks from visit 2; stool positive for Clostridium difficile toxin at screening; primary sclerosing cholangitis; history of gastrointestinal surgery within 8 weeks of visit 2; malignancy or underlying immunocompromised conditions; participation in another clinical trial within 30 days prior to screening; abnormal laboratory tests at screening, including white blood cell count (<3×109/L), hemoglobin (<100 g/L), or liver tests; pregnancy or lactation (or a planned pregnancy within 7 months of study completion); males or females unwilling to use effective contraception for the duration of and 7 months after finishing the investigational product (the partners of male patients were required to use 2 forms of contraception, and male patients were not permitted to donate sperm); and any other patient considered unsuitable for inclusion by the investigators. Patients with exposure to the following treatments were also excluded: cyclosporine A, tacrolimus, or mycophenolate mofetil within 1 month prior to visit 2; anti-TNF-α agents within 2 months prior to visit 2 or during 5 halflives (drug elimination time), whichever was longer; leukocytapheresis or granulocytapheresis within 1 month prior to visit 2; prior exposure to any drugs that target α4β7 integrins or the mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule pathway, including abrilumab; use of topical (rectal) aminosalicylic acid agent (e.g., mesalamine) or topical (rectal) steroid within 2 weeks prior to visit 2; intravenous or intramuscular corticosteroids from 2 weeks prior to screening and during the screening period; live attenuated vaccine within 1 month prior to Visit 2 or plans to receive any live attenuated vaccine during the study; and any antibiotics, antivirals, or antifungals for treatment of infection (intravenous within 30 days prior to visit 2, oral within 14 days prior to visit 2).

4. Treatments

In the double-blind period, patients in the placebo and abrilumab 21 mg or 70 mg groups received the respective investigational product by SC injection on day 1 and at weeks 2, 4, and 8. In the abrilumab 210 mg group, patients received abrilumab 210 mg SC on day 1, followed by placebo SC at weeks 2, 4, and 8. In the open-label period, all patients received abrilumab 210 mg SC at week 12 and every 12 weeks until and including week 48. In all treatment groups, patients received 3 injections per dose (1 mL/syringe; total 3 mL per dose). The placebo was identical in appearance to abrilumab. All SC injections during both treatment periods were administered into different sites on the patient’s anterior abdominal wall, thigh, or upper arm.

5. Efficacy Variables and Assessments

The primary endpoint was clinical remission at week 8 defined as a total Mayo score ≤ 2 points, and with no individual subscore >1 point. The secondary and exploratory outcome variables were the following: induction of response at week 8 as assessed by the total Mayo score, whereby response is defined as a decrease ≥3 points and 30% in total Mayo score compared to baseline (visit 1), and with an accompanying decrease in the subscore for rectal bleeding of ≥ 1 point or with an absolute subscore for rectal bleeding of 0 or 1; mucosal healing at week 8 as assessed by rectosigmoidoscopy, defined as an absolute subscore for rectosigmoidoscopy of 0 or 1; response at week 12 as assessed by the partial Mayo score (PMS), defined as reduction by ≥ 2 points and 25% in PMS compared to baseline (visit 1); sustained response rates at week 24 in patients who achieved response at week 12 by PMS; the safety and tolerability of abrilumab 21 mg, 70 mg, and 210 mg through 48 weeks of dosing exposure and for 28 weeks after ceasing dosing; PK evaluation (serum abrilumab concentrations); the PD effects of abrilumab on circulating lymphocytes, as measured by flow cytometry and immunophenotyping and receptor occupancy assay coupled with absolute count measurements (the IPAC assay assessed free and total α4β7 on naive CD4 T cells as well as changes in α4β7-high central memory CD4 T cell absolute counts [cells/μL]); and the proportion of patients who developed anti-drug antibodies to abrilumab.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were measured using the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire [18], the Patient Global Rating of Change, and UC PRO, and were recorded by patients on an electronic PRO device. Data were collected on electronic case report forms by the study investigators and transferred to Medidata Rave®, a web-based data capture system.

Disease remission and response rates were estimated using the Mayo score [19], a composite index of 4 items (stool frequency, rectal bleeding, rectosigmoidoscopy findings, and physician’s global assessment). Each item is graded semi-quantitatively on a score of 0 to 3 for a maximal total score of 12. Patients recorded symptoms in the Mayo daily symptom diary.

6. Safety Assessment

AEs were recorded from the time of randomization to the end of the follow-up period, and serious AEs (SAEs) were recorded from the time of informed consent. AE preferred terms were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 19.1. AEs were graded using the National Cancer Institute CTCAE version 4.0, and investigators judged and recorded the likelihood of relationship of AEs to study treatment, with reference to a causality guide. Neurological AEs potentially consistent with PML were referred to an adjudication committee, which included several specialists not involved in the study. Other safety assessments included laboratory assessments, tuberculosis testing (including chest radiograph), pregnancy tests, neurological examination, electrocardiogram, and stool samples for C. difficile toxin.

7. Statistical Analyses

No formal statistical analysis was conducted; instead, the efficacy and safety of abrilumab were assessed visually using descriptive statistics and plots. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (n, mean, SD, minimum, median, and maximum values). The efficacy and safety analysis sets in the double-blind period included all patients who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of investigational product, and the corresponding analysis sets in the open-label period were all patients who had at least 1 dose of open-label abrilumab 210 mg treatment in the open-label period. The PK evaluation was conducted in all patients for whom PK data were available, and the PD evaluation in all patients for whom PD data were available. No formal sample size calculation was performed, but a total of 48 patients were planned for randomization. The number of patients to be recruited into each dose arm (12 patients) was chosen based on the feasibility assessment to allow comparison of Japanese data with the global phase IIb study17 before joining future international phase III studies without significant delay. Data were analyzed using the SAS® System (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

8. Change to Planned Analyses

Prior to unblinding, the PD analysis set for the double-blind period and the analysis sets for the open-label and safety follow-up periods were defined, as these sets were not defined in the study protocol.

RESULTS

1. Patient Disposition

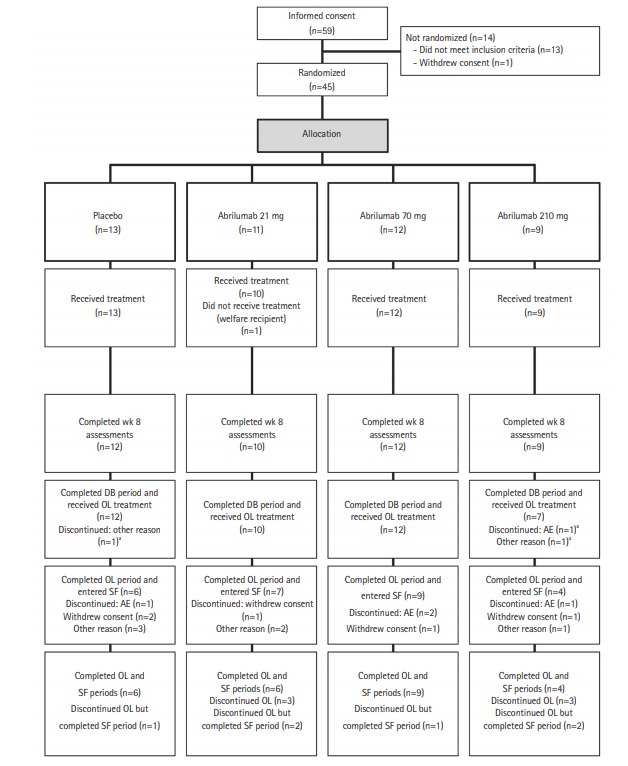

The patient disposition is shown in Fig. 2. In total, 59 patients were enrolled at 23 centers in Japan. Of these, 45 patients were randomized (abrilumab 21 mg: 11 patients, abrilumab 70 mg: 12 patients, abrilumab 210 mg: 9 patients, placebo: 13 patients). Fourteen patients were not randomized because they either did not meet the inclusion criteria or met exclusion criteria. Of the 45 randomized patients, 1 patient in the abrilumab 21 mg group did not receive the investigational product, and of the 44 patients (97.8%) dosed, 43 patients (95.6%) completed the week 8 assessment for the primary analysis and 41 patients (91.1%) completed the double-blind period. Three patients (6.7%) were discontinued from the study in the double-blind period, but all of these patients completed the safety follow-up period. The reasons for discontinuation from the double-blind period were AE, insufficient effect (placebo), and overdose (abrilumab 210 mg) in 1 patient each (2.2%). All 41 patients who completed the double-blind period were enrolled in the open-label period, of whom 26 patients (63.4%) completed the open-label period and entered into the safety follow-up period. Of these, 25 patients (61.0%) completed the safety follow-up period. Fifteen patients (36.6%) were discontinued from the study in the open-label period: 8 patients (19.5%) entered the safety follow-up period and 6 patients (14.6%) completed the safety follow-up period. Reasons for discontinuation of the open-label period included withdrawal of consent (5 patients, 12.2%), AE (4 patients, 9.8%), and other (6 patients, 14.6%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient disposition. aThe 3 patients who discontinued the double-blind (DB) period all completed the safety follow-up (SF) period. OL, open-label; AE, adverse event.

2. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics among the 4 treatment groups. The treatment groups were generally wellbalanced for demographic and patient characteristics. All patients were Asian. The mean age was 39.2 years and was somewhat higher in the abrilumab 21 mg group than the other groups. The proportion of male patients was 65.9% overall and was similar across the treatment groups. Most patients in all groups were non-smokers. Mean duration of UC was 5.29 years; this was slightly longer in the abrilumab 21 mg group (mean, 6.75 years) and somewhat shorter in the abrilumab 210 mg group (mean, 3.29 years). There were no notable differences between groups in prior medication. The most commonly used prior medication at baseline in the double-blind period was 5-aminosalicylates (88.6% of all patients). Body weight and body mass index were similar across all treatment groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=13) | Abrilumab |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 mg (n=10) | 70 mg (n=12) | 210 mg (n=9) | ||

| Age (yr) | 38.0±15.1 | 45.9±15.6 | 39.8±11.5 | 33.1±11.4 |

| Male sex | 8 (61.5) | 7 (70.0) | 8 (66.7) | 6 (66.7) |

| Body weight (kg) | 61.6±9.6 | 59.9±8.0 | 57.0±9.2 | 61.5±8.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.23±3.22 | 20.78±1.53 | 20.00±2.65 | 21.74±2.53 |

| Duration of UC (yr) | 5.41±2.16 | 6.75±6.03 | 5.43±3.68 | 3.29±2.55 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 3 (25.0) | 0 |

| Former | 3 (23.1) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (33.3) | 2 (22.2) |

| Never | 10 (76.9) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (77.8) |

| Previous medications | ||||

| Use of 5-ASA at DB baseline | 11 (84.6) | 10 (100.0) | 10 (83.3) | 8 (88.9) |

| Use of oral corticosteroids at DB baseline | 3 (23.1) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Use of immunomodulators at DB baseline | 7 (53.8) | 3 (30.0) | 8 (66.7) | 5 (55.6) |

| Use of 5-ASA at OL baseline | 11 (91.7) | 10 (100.0) | 10 (83.3) | 7 (100.0) |

| Use of oral corticosteroids at OL baseline | 3 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Any prior use of anti-TNF-α agents | 8 (61.5) | 5 (50.0) | 7 (58.3) | 6 (66.7) |

Values are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; DB, double-blind; OL, open-label.

3. Primary Efficacy Endpoint

Clinical remission at week 8 was numerically higher in the abrilumab groups (4/31 patients overall [12.9%]: 1/10 patient [10.0%] in the abrilumab 21 mg group, 2/12 patients [16.7%] in the 70 mg group, and 1/9 [11.1%] in the abrilumab 210 mg group) than the placebo group (0/13 patients) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Efficacy Endpoints in the Efficacy Set

| Outcome | Placebo (n=13) | Abrilumab |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 mg (n=10) | 70 mg (n=12) | 210 mg (n=9) | ||

| Remission rate at week 8a | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (11.1) |

| Response rate at week 8b | 7 (53.8) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (66.7) |

| Mucosal healing rate at week 8c | 4 (30.8) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (44.4) |

| Response rate at week 12d | 6 (46.2) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (66.7) |

| Sustained responsee | 4 (30.8) | 3 (30.0) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (44.4) |

Values are presented as number (%).

Total Mayo score ≤2 points, and with no individual subscore >1 point.

Decrease in ≥3 points and 30% in total Mayo score compared with baseline (visit 1, week 4), and with an accompanying decrease in the subscore for rectal bleeding of ≥1 point or with an absolute subscore for rectal bleeding of 0 or 1.

An absolute Mayo subscore for rectosigmoidoscopy of 0 or 1.

Reduction by ≥2 points and 25% in partial Mayo score compared with baseline (visit 1).

Achieving the criteria for response assessed by partial Mayo score at both week 12 and week 24.

4. Secondary and Exploratory Endpoints

Table 2 also shows the response rates at weeks 8 and 12, the mucosal healing rate at week 8, and the sustained response rates at weeks 12 and 24. The response rate at week 8 was numerically higher than placebo only in the abrilumab 210 mg group, but at week 12 was numerically higher than placebo in both the 70 mg and 210 mg groups. The mucosal healing rate was numerically higher in the abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg groups as compared with the placebo group. The proportion of patients achieving a sustained response at both week 12 and week 24 was numerically higher in the abrilumab 210 mg group than the placebo group.

The exposure-response relationship for total Mayo score showed a trend across the treatment groups. A trend of reduction in PMS was observed in the abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg groups at week 8 and week 12. There was no apparent treatment effect of abrilumab on stool frequency up to week 12 as compared with the placebo group, but a numerical trend of improvement in rectal bleeding was observed for abrilumab, while numerical trends of improvement in rectosigmoidoscopy and physician’s global assessment score were observed with abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg. A treatment effect on PMS and individual Mayo subscores was not apparent with treatment with abrilumab 210 mg given every 12 weeks during the open-label period.

Serum abrilumab concentrations showed a dose-proportional increase within the investigated dose range at week 2, and between the abrilumab 21 mg group and the 70 mg group at weeks 4, 8, and 12. Abrilumab treatment led to a reduction in free and total α4β7 levels on naïve CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood. Maximal reduction in free α4β7 levels compared to baseline was observed at the first post-dose assessment (week 2) and persisted at nearly that level through week 12. No serum antibodies to abrilumab were detected in patients receiving abrilumab.

5. Patient-Reported Outcomes

A numerical trend of improvement in Patient Global Rating of Change was observed in the abrilumab groups compared with the placebo group, and a trend towards improvement in total Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire score and the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire subscores of bowel systems, emotional health, systemic systems, and social function was observed in the abrilumab 210 mg group compared with the placebo group (data not shown).

Regarding UC PRO, no treatment effect of abrilumab was noted in the number of bowel movements, diarrhea, coping activities, emotional impact, and daily impact on life. The abrilumab 210 mg group showed the greatest improvement from baseline in emotional impact and daily impact in life at week 8, but without statistical testing, no significant between-group differences could be determined. Treatment effect on gastrointestinal symptoms and systemic symptoms was observed with abrilumab 210 mg compared with placebo (data not shown).

6. Safety

Forty-four patients received at least 1 dose of study drug and provided safety data. Median duration of exposure ranged from 287.0 to 417.5 days in the abrilumab groups and was 334.0 days in the placebo group. In the double-blind period, fewer patients in the abrilumab groups experienced at least 1 AE compared with those in the placebo group (44.4%–60.0% vs. 69.2%). An SAE was reported in 1 patient (10.0%) in the abrilumab 21 mg group (UC), while 1 patient (11.1%) in the abrilumab 210 mg group reported an SAE with severity grade 3, leading to discontinuation of abrilumab (cerebral infarction). Treatment-related AEs were reported in 2 patients (20.0%) in the abrilumab 21 mg group, 1 patient (11.1%) in the abrilumab 210 mg group, and 2 patients (15.4%) in the placebo group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment-Related Adverse Events by MedDRA Preferred Term in the Double-Blind and Open-Label Periods

| Preferred term | Placebo (n=13) | Abrilumab |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 mg (n=10) | 70 mg (n=12) | 210 mg (n=9) | ||

| Double-blind period | ||||

| Any adverse event | 2 (15.4) | 2 (20.0) | 0 | 1 (11.1) |

| Malaise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) |

| Injection site swelling | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 1 (11.1) |

| Enterocolitis viral | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White blood cell count decreased | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Asthma | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Open-label period | ||||

| Any adverse event | 4 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (14.3) |

| Colitis ulcerative | 0 | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 1 (14.3) |

| Enteritis | 0 | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 |

| Influenza | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Sinusitis | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphadenitis | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cough | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergic cough | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Edema peripheral | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Gall bladder polyp | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Genital hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 |

Values are presented as number (%). Preferred terms in this table were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 19.1.

In the open-label/safety follow-up period, the proportion of patients experiencing at least 1 AE was lower in the abrilumab groups (83.3%–90.0%) than in those who received placebo in the double-blind period (91.7%). No deaths were reported. In the open-label/safety follow-up period, SAEs were reported in 6 patients overall (14.6%). One patient (8.3%) from the original placebo group had 1 SAE of anemia and 1 SAE of chronic sinusitis, and 1 patient (8.3%) had 1 SAE of worsening UC. In patients from the original abrilumab 21 mg group, 1 patient (10.0%) had 1 SAE each of contrast media allergy, UC, polychondritis, and 6th nerve paresis. In patients from the original abrilumab 70 mg group, 2 patients (16.7%) each had 1 SAE of UC and 1 (8.3%) had an SAE of enteritis.

AEs leading to discontinuation of the study drug were reported in 2 patients (16.7%) in the 70 mg group, 1 patient (14.3%) in the 210 mg group, and 1 patient (8.3%) who received placebo in the double-blind period. Treatment-related AEs were reported in 1 to 3 patients (14.3% to 30.0%) in the abrilumab groups and 4 patients (33.3%) in the placebo group (open-label period) (Table 3).

No AEs with severity equal to or greater than grade 4 were reported in either the double-blind or open-label periods. All AEs reported in the double-blind period were CTCAE grade 1 or grade 2 in severity, except for the grade 3 AE (cerebral infarction) in 1 patient (11.1%) from the original abrilumab 210 mg group. In the open-label/safety follow-up period, AEs with CTCAE grade 3 were reported in 1 patient (10.0%) from the original abrilumab 21 mg group (worsening of UC, contrast media allergy, polychondritis, and 6th nerve paresis), 3 patients (25.0%) from the original abrilumab 70 mg group (worsening of UC and enteritis), and 3 patients (25.0%) from the original placebo group (anemia, chronic sinusitis, and UC). Of these, UC and enteritis in the patient from the original abrilumab 70 mg group and anemia in the patient from the placebo double-blind group were judged by the investigator to be related to abrilumab.

There was no PML reported by the adjudication committee during the study. There were no trends indicative of clinically important treatment-related laboratory abnormalities reported in the study.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the proportion of Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe UC achieving clinical remission at week 8 was numerically higher in the abrilumab groups compared with the placebo group. Response rates at week 8 were also higher with abrilumab 210 mg than placebo, and mucosal healing at week 8 improved at dosages of abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg compared with placebo. While no statistical analysis was performed, and the numbers were small, the numerically higher clinical remission rates found with abrilumab vs. placebo in this Japanese study do reflect those in the global study [17], where the odds of achieving clinical remission at week 8 were significantly greater with abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg than with placebo. Indeed, the clinical remission rates with the 70 mg dose were 16.7% in the Japanese population and 13.5% in the global population.

In the present study, the clinical remission rates of 16.7% and 11.1% for the abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg groups, respectively, are lower than those in studies of vedolizumab, another α4β7 inhibitor. Feagan et al. [20] found clinical remission rates at week 6 of 32% to 33% with vedolizumab compared with 14% with placebo, and the difference between the 2 groups was statistically significant. In that study, clinical remission was defined differently, as a UC clinical score of 0 or 1 and a modified Baron score of 0 or 1 with no evidence of rectal bleeding [20]. In 2013, the GEMINI 1 study group showed response rates at week 6 (reduction in total Mayo score of ≥ 3 points and a decrease of ≥ 30% from baseline) of 47.1% and 25.5% among patients in the vedolizumab group and placebo group, respectively [14]. However, these response rates are not dissimilar to those found in the Japanese patients in this study. Indeed, the response rates of 50.0% and 66.7% with the higher dosages of abrilumab in our study are higher, although the numbers were small and not statistically tested. In the future, a larger clinical trial is needed to more accurately demonstrate the efficacy of abrilumab.

The exposure-response relationship for total Mayo score showed a trend across the treatment groups, and there was also a trend towards reduction in PMS observed in the abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg groups at week 8 and week 12. There was no apparent treatment effect of abrilumab on stool frequency up to week 12, but there was a numerical trend of improvement in rectal bleeding, and numerical trends of improvement in rectosigmoidoscopy and physician’s global assessment score at the 2 higher doses. Abrilumab 210 mg given every 12 weeks during the open-label period showed no apparent treatment effect on PMS and individual Mayo subscores. Specifically, when the effects of abrilumab on sustained response were evaluated at week 24 in patients who achieved a response at week 12 by PMS, no obvious sustained response was observed. Serum abrilumab concentrations increased dose-dependently within the investigated dose range at week 2, and between the abrilumab 21 mg and 70 mg groups at weeks 4, 8, and 12.

Consistent with findings from the larger phase II UC study [17], the maximal reduction in free α4β7 was close to 90% of the baseline value and the maximal reduction in total α4β7 was close to 50% of the baseline value. While these measurements were made on CD4+ naïve T cells, similar results were observed on CD4+ memory T cells (data not shown). Unlike in the larger phase II study of abrilumab in patients with UC, abrilumab did not induce significant post-dose differences in circulating memory CD4+ T cells, central memory CD4+ T cell counts, or α4β7-high central memory CD4+ T cell counts between baseline and week 12 (in the 21 mg SC and 70 mg SC groups), and between baseline and week 8 (in the 210 mg SC group) in this study. The reason for this may be the small sample size.

No serum antibodies to abrilumab were detected in patients receiving abrilumab in this study. In the global study, 1 patient in the abrilumab 70 mg group and 1 patient in the abrilumab 210 mg group were positive for anti-abrilumab binding antibodies [17].

Abrilumab was well tolerated in Japanese patients with UC at the dosages of 21 mg, 70 mg, and 210 mg SC in the doubleblind period. Fewer patients in the abrilumab groups experienced at least 1 AE compared with those in the placebo group (44.4%–60.0% vs. 69.2%). Some comparisons can be made between this Japanese study and the original global study of abrilumab. The overall incidence of AEs in the double-blind period in this study is similar to that during the double-blind period in the global study of abrilumab, where 63.0% of patients across all the abrilumab groups compared with 68.1% of those in the placebo group reported at least 1 treatmentemergent AE [17]. SAEs were reported by 14 patients (12%) in the placebo group compared with 16 (6.7%) in the abrilumab groups during the double-blind period in the global study. In the double-blind period in the current study, SAEs occurred in 1 patient (10.0%) in the abrilumab 21 mg group and 1 (11.1%) in the abrilumab 210 mg group. Worsening of UC was the only SAE recorded in more than 1 patient treated with abrilumab in the global study, during the double-blind period. In this Japanese study, worsening of UC was reported as an SAE in only 1 patient in the double-blind period (abrilumab 21 mg), but occurred in 3 patients in the open-label period (1 from the original double-blind abrilumab 21 mg group, and 2 from the original double-blind 70 mg group).

Differences in AEs between European and Asian populations have been found previously, including in patients with IBD, and the relationships of these differences with genetic polymorphisms have been described. For example, it is known that thiopurine-induced leukopenia occurs more frequently in Asian patients than Europeans with IBD, and that NUDT15 is a pharmacogenetic determinant for thiopurineinduced leukopenia, including in Asians [21,22]. The NUDT15 variant is most common in East Asians and is also strongly associated with mercaptopurine intolerance in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia [23].

The results of this study must be reviewed in light of the small number of patients recruited, a design that was not intended to allow efficacy conclusions, and the fact that all patients were Japanese, limiting extrapolation of the results to other populations given possible ethnic differences [24]. In addition, the effect of prior anti-TNF agents on the efficacy of abrilumab could not be evaluated due to the small number of patients in this study.

In conclusion, the results of the present study show that abrilumab 70 mg and 210 mg yielded numerically more favorable results in terms of the primary efficacy endpoint (remission rate at week 8) and secondary efficacy endpoints (response at weeks 8 and 12, mucosal healing at week 8) compared with placebo, with the 210 mg dose showing more consistent treatment effects. Overall, abrilumab was well tolerated in Japanese patients with UC.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Yili Pritchett, biostatistician at MedImmune LLC, for assistance in interpreting the study results.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was supported by AstraZeneca K.K. and Amgen Inc. Marion Barnett of Edanz Medical Writing provided medical writing assistance, which was funded by AstraZeneca through EMC K.K. in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

T.H. has received consultancy fees from AbbVie Japan, JIMRO, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, EA Pharma, Eli Lilly Japan KK, Pfizer Japan Inc., Nippon Kayaku Co. Ltd., and Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and grants from Zeria Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Holdings Co. Ltd., AbbVie Japan, EA Pharma, and JIMRO. R.G. is an employee of MedImmune, LLC, a subsidiary of AstraZeneca. M.N. is an employee of AstraZeneca K.K. B.S. is a former employee and current shareholder of Amgen Inc. S.N. has received grants from Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, EA Pharma, AbbVie Japan, Asahi Kasei Medical, JIMRO, Otuka Pharmaceutical Factory, ZERIA Pharmaceuticals, Mochida Pharmaceutical, and Astellas Pharma, and lecture fees from AbbVie Japan, Janssen Pharmaceutical, EA Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, ZERIA Pharmaceuticals, and Mochida Pharmaceutical. A.M., S.M., S.S., T.A., Y. Sameshima, and Y. Suzuki have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Hibi T. Methodology: Hibi T, Gasser RA, Sullivan BA. Formal analysis: Hibi T, Gasser RA, Nii M, Sullivan BA. Investigation: Motoya S, Ashida T, Sai S, Sameshima Y, Nakamura S, Maemoto A, Suzuki Y, Sullivan BA. Writing, review, and editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Shared Study Report FY 2016 on “Research on intractable inflammatory bowel disease” (Suzuki Group) Ulcerative colitis/Crohn’s disease diagnostic criteria/treatment guideline. http://www.ibdjapan.org/pdf/doc01.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2018.

- 2.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2010 Public Health Report (Table 65 No. of patients receiving medical treatment for refractory diseases by sex, age group and disease). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Web site. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html. Accessed May 6, 2018.

- 5.Asakura K, Nishiwaki Y, Inoue N, Hibi T, Watanabe M, Takebayashi T. Prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:659–665. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoie O, Wolters F, Riis L, et al. Ulcerative colitis: patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1692–1701. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiwatashi N, Yao T, Watanabe H, et al. Long-term follow-up study of ulcerative colitis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30 Suppl 8:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501–523. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, Tremaine W, American Gastroenterological Association American Gastroenterological Association Institute medical position statement on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:935–939. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki Y, Motoya S, Hanai H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0922-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:305–353. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arihiro S, Ohtani H, Suzuki M, et al. Differential expression of mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Pathol Int. 2002;52:367–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, et al. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesterberg PE, Winsor-Hines D, Briskin MJ, et al. Rapid resolution of chronic colitis in the cotton-top tamarin with an antibody to a gut-homing integrin alpha 4 beta 7. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1373–1380. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picarella D, Hurlbut P, Rottman J, Shi X, Butcher E, Ringler DJ. Monoclonal antibodies specific for beta 7 integrin and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) reduce inflammation in the colon of scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2099–2106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandborn WJ, Cyrille M, Hansen MB, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrilumab in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.035. [published online ahead of print November 22, 2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: a randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2499–2507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang SK, Hong M, Baek J, et al. A common missense variant in NUDT15 confers susceptibility to thiopurine-induced leukopenia. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1017–1020. doi: 10.1038/ng.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu X, Wang XD, Chao K, et al. NUDT15 polymorphisms are better than thiopurine S-methyltransferase as predictor of risk for thiopurine-induced leukopenia in Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:967–975. doi: 10.1111/apt.13796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JJ, Landier W, Yang W, et al. Inherited NUDT15 variant is a genetic determinant of mercaptopurine intolerance in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1235–1242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi T, Hisamatsu T, Suzuki Y, et al. Predicting outcomes to optimize disease management in inflammatory bowel disease in Japan: their differences and similarities to Western countries. Intest Res. 2018;16:168–177. doi: 10.5217/ir.2018.16.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]