Abstract

Background

National guidelines recommend against cancer screening for older individuals with less than a 10-year life expectancy, but it is unknown if this population desires ongoing screening.

Objective

To determine (1) if older individuals with < 10-year life expectancy have future intentions for cancer screening, (2) if they recall a doctor previously suggesting that screening is no longer needed, and (3) individual characteristics associated with intentions to seek screening.

Design

National Social life Health and Aging Project (2015–2016), a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey.

Participants

Community-dwelling adults 55–97 years old (n = 3816).

Main Measures

Self-reported: (1) mammography and PSA testing within the last 2 years, (2) future intentions to be screened, and (3) discussion with a doctor that screening is no longer needed. Ten-year life expectancy was estimated using the Lee prognostic index. Multivariate logistic regression analysis examined intentions to pursue future screening, adjusting for sociodemographic and health covariates.

Key Results

Among women 75–84 with < 10-year life expectancy, 59% intend on future mammography and 81% recall no conversation with a doctor that mammography may no longer be necessary. Among men 75–84 with < 10-year life expectancy, 54% intend on future PSA screening and 77% recall no discussions that PSA screening may be unnecessary. In adjusted analyses, those reporting recent cancer screening or no recollection that screening may not be necessary were more likely to want future mammography or PSA screening (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Over 75% of older individuals with limited life expectancy intend to continue cancer screening, and less than 25% recall discussing with physicians the need for these tests. In addition to public health and education efforts, these results suggest that older adults’ recollection of being told by physicians that screening is not necessary may be a modifiable risk factor for reducing overscreening in older adults with limited life expectancy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05064-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: cancer screening, aging, patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

Cancer screening remains a standard aspect of preventive medical care. However, it is increasingly recognized that the priority of engaging in certain preventive medical interventions should change as individuals get older or life expectancy becomes limited. For cancer screening, studies indicate there is a significant lag time to benefit; for breast cancer screening, it is approximately 10 years,1 and for prostate cancer screening likely longer than 10 years.2 Consequently, those with < 10 years of estimated life expectancy are unlikely to have lower cancer-specific mortality due to screening.3 Meanwhile, older, frail, and/or cognitively impaired adults are at greater risk for immediate potential harms of screening and follow-up procedures.4 As a result, professional organizations and guidelines, such as the Choosing Wisely campaign, recommend against cancer screening for those who are older (generally > 75 years old), with less than a 10-year life expectancy, and for whom the potential for adverse events, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment are high.5–10

Despite national guidelines, rates of cancer screening among older adults with limited life expectancy remain high. A study utilizing nationally representative NHIS 2008 and 2010 data, for example, found that 36% of women with < 5-year life expectancy and 56% of women > 75 years old reported a screening mammogram in the past 2 years.11 Similarly for prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests, 30–50% of men with < 10-year life expectancy had recent PSA tests,12–14 and these rates declined only slightly following changes to national guidelines.15 High rates of overscreening likely reflect enthusiasm for what is viewed as a positive health behavior,16 overestimation of the benefits, low awareness of the potential harms, and a reluctance to stop.17–19 In addition, physicians often have time limitations preventing and/or general discomfort in having discussions related to stopping screening and in accurately estimating life expectancy.20

Gaps remain in our understanding of patient- and provider-related contributors to continuing cancer screening despite limited life expectancy. Studies examining adults’ enthusiasm for cancer screening generally focus on younger individuals and do not include measures of life expectancy or large samples of older adults.16 An assessment of whether older adults, especially those with limited estimated life expectancies, have future intentions for undergoing screening is needed as it could guide physician communication strategies for shared decision-making. In addition, it is unclear how many adults, for whom cancer screening is not recommended, are even aware that there exist recommendations to avoid these tests or recall having a discussion with their doctors.

Therefore, we used nationally representative 2015–2016 data from the National Social life Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) to determine (1) if older adults with limited life expectancies have future intentions to pursue screening, (2) if they recall a doctor previously suggesting that screening is no longer needed, and (3) individual characteristics independently associated with older adults’ future intentions to seek screening.

METHODS

Study Sample

We used the National Social Life Health and Aging Project, Wave 3 sample (NSHAP-W3), a US nationally representative probability sample of 4776 older adults. Surveys were conducted face-to-face with Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) between September 2015 and September 2016. NSHAP-W3 included community-dwelling adults > 57 years, and as a sampling strategy, included co-resident spouses and partners of any age. Individuals unable to complete the interview due to physical or cognitive limitations were not enrolled. Details on the sampling design, recruitment, and inclusion criteria are published elsewhere and available online.21,22 We made the following exclusions for the analysis: individuals younger than 55 years old (n = 788) or with prior histories of breast cancer (n = 81) or prostate cancer (n = 91). This yielded a final sample of 3816 individuals, including 2084 women and 1732 men. All respondents provided written informed consent and the protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Chicago and National Opinion Research Center (NORC).

Cancer Screening

We focus on breast and prostate cancer screening as each test has a similar lag time to survival benefit of 10 years or greater and each is associated with changes in national guidelines over the last decade. We characterized self-reported screening behavior related to PSA tests and mammograms using three questions. First, we ask “Do you plan to have regular mammograms or PSA tests in the future?” with responses of “Yes,” “No,” or if volunteered “I do what my doctor says.” This variable is used as the primary outcome in regression analysis. Second, we ask “How long has it been since you had a mammogram or PSA test?” Responses within a 2-year interval represented a “recent screen” based on national guidelines.6,7,9 Prior studies suggest reasonable accuracy of self-reported screening as compared to medical records for both mammograms and PSA tests.23,24 Third, we ask “Has a doctor ever suggested you may no longer need regular mammograms or PSA tests?” with responses of “Yes” or “No.”

Life Expectancy

The Lee prognostic index includes 12 items that together predict 5- and 10-year life expectancy.25,26 We constructed a slightly modified version of the Lee prognostic index utilizing available items from NSHAP. The following 10 items were included directly from NSHAP: (1) Age (ages 60–64, 1 point; 65–69, 2 points; 70–74, 3 points; 75–79, 4 points; 80–84, 5 points; > 84, 7 points); (2) male sex (2 points); (3) current tobacco use (2 points); (4) body mass index < 25 (1 point); (5) diabetes (1 point); (6) non-skin cancers (2 points); (7) chronic lung disease (2 points); (8) heart failure (2 points); (9) difficulty bathing (2 points); and (10) difficulty managing finances (2 points). The following two items in the original Lee index were substituted with available items from NSHAP: (1) “difficulty walking several blocks” was substituted with the NSHAP item “difficulty walking one block” (2 points); (2) “difficulty pushing/pulling large objects” was substituted with the NSHAP item “difficulty performing housework” (1 point). We compared the performance of the original Lee index in predicting 4-year mortality to the modified Lee index in predicting 5-year mortality in NSHAP and found consistent performance (Table 1). The range of the modified Lee index is 0–26 points, and we used cutoff scores of 8+ points and 12+ points corresponding to a < 10-year life expectancy and < 5-year life expectancy, respectively, as determined in prior literature.25

Table 1.

Validation of the Modified Lee Prognostic Index for Use in NSHAP Compared with the Original Lee Prognostic Index in HRS

| Points | Original Lee index, HRS 1998 wave | Modified Lee index in NSHAP 2010–2011 wave |

|---|---|---|

| 4-year mortality (%)* | 5-year mortality (%) | |

| (n = 11,701) | (n = 3161) | |

| 0–5 points | 4% | 4% |

| 6–9 points | 15% | 19% |

| 10–13 points | 42% | 38% |

| 14+ points | 64% | 59% |

HRS health and retirement study, NSHAP national social life and aging study

*Lee, S. et al. 2006; JAMA 295(7):801–80826

Covariates

We measured several covariates known to be related to cancer screening behavior.27–29 Sociodemographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education. Health status variables include self-rated physical health, and the NSHAP comorbidity index, a measure of 12 different health conditions.30 Depressive symptoms were measured using a modified Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale, ranging 0–33 points,31 and categorized as normal (0–8 points) or moderate to severe (9+ points).16 Cognition was measured using a survey-adapted Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-SA), with scores ranging 0–30 points.32,33 Functional status was measured as needing no help (0 points), some help (0.5 points), or being unable to do (1 point) seven Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) and five Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). Individuals were grouped as no dependence (< 1 point) or any dependence (1+ points).

Statistical Analysis

We determined rates of each cancer screening behavior by age and 10-year life expectancy. We then used separate multivariate logistic regressions for men and women to determine the association between future intentions to pursue screening and covariates. Covariates included in the regression models included the Lee index, in categories of < 5-year, 5–10-year, and > 10-year life expectancy, self-reported recent screen, no recalled discussion that screening may “not be necessary,” education, ethnicity/race, marital status, MoCA-SA score, and depressive symptoms. We did not include variables in the model that were taken into account by the Lee index. We separately measured the adjusted association of age with future intentions to screen by including the above covariates, but leaving out the Lee Index, given the high correlation between age and the Lee index (r = 0.65). Due to missing data from individual covariates, 175 respondents and 242 respondents were excluded when model fitting for the mammography and PSA test models, respectively. All analyses were performed using Stata 15 including sample weights to account for the complex sampling design.34

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample appear in Table 2. The mean age of men and women in the sample was 69 years and 69.3 years, respectively. As estimated by the Lee index, approximately 21% of the sample had a life expectancy less than 10 years, including 5% who had less than a 5-year life expectancy.

Table 2.

Weighted Sample Characteristics in the National Social life Health and Aging Project (n = 3816)

| Variables | N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (range 55–97) | 55–59 | 670 | (27.4) |

| 60–69 | 1302 | (41.6) | |

| 70–74 | 665 | (12.7) | |

| 75–84 | 858 | (13.8) | |

| 85+ | 321 | (4.4) | |

| Sex | Male | 1732 | (47.4) |

| Female | 2084 | (52.6) | |

| Ethnicity/race | White | 2670 | (77.1) |

| AA | 591 | (11.4) | |

| Hispanic | 423 | (7.8) | |

| Other | 123 | (3.7) | |

| Marital | Unmarried | 1267 | (34.1) |

| Married/partnered | 2549 | (65.9) | |

| Education | <HS | 561 | (11.1) |

| HS/GED | 900 | (23.6) | |

| Some college | 1339 | (36.7) | |

| Bachelor+ | 1016 | (28.6) | |

| Health status | |||

| Lee prognostic index* | < 5 years | 260 | (4.5) |

| < 5–10 years | 789 | (16.9) | |

| > 10 years | 2559 | (78.6) | |

| Comorbidity index† (range 0–12) | 0 | 1108 | (29.8) |

| 1 | 1202 | (31.6) | |

| 2 or 3 | 1126 | (28.6) | |

| 4+ | 380 | (10.0) | |

| Self-rated health | Poor/fair | 915 | (22.4) |

| Good/VG/Exc | 2895 | (77.6) | |

| ADL or IADL dependence‡ | None | 2861 | (78.2) |

| Any | 955 | (21.8) | |

| Depressive symptoms§ (range 0–33) | Normal (0–8) | 2882 | (75.7) |

| Moderate/severe (9+) | 932 | (24.3) | |

| MoCA (range 0–30)|| | Median (IQR) | 24 | (21–26) |

Percentages and raw numbers may not match exactly due to sampling weights

HS high school, VG very good, Exc excellent, ADL activities of daily living, IADL independent activities of daily living, MoCA Montreal cognitive assessment

*Life expectancy is estimated based on the modified Lee prognostic index26

†Comorbidities were measured based on the NSHAP comorbidity index30

‡ADL and IADL dependence was determined based on having no dependence or any dependence in seven IADLs and 5 ADLs

§Depressive symptoms determined based on adaptation of Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale31

||MoCA was measured using a survey-adapted MoCA32

Table 3 shows the percentages of cancer screening behaviors, stratified by age and estimated life expectancy. For women age 75–84 years old with < 10-year estimated life expectancy, 68% reported a recent screening mammograms, 59% intend on having regular mammograms in the future, and 81% reported never discussing with a doctor that screening may not be necessary. For men age 75–84 years old with < 10-year estimated life expectancy, 66% reported a recent PSA test, 54% intend to have a regular PSA tests in the future, and 76% reported never discussing with a doctor that screening may not be necessary.

Table 3.

Weighted Frequencies of Cancer Screening Behaviors by Age and Life Expectancy

| Age 55–74 | Age 75–84 | Age 85+ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE<10 | LE>10 | LE<10 | LE>10 | LE<10 | LE>10 | |

| Breast cancer screening | N = 136 | N = 1232 | N = 147 | N = 283 | N = 149 | N = 27 |

| Self-report mammogram within the last 2 years | 69.1 | 77.3 | 67.8 | 72.2 | 44.0 | 67.3 |

| Plan to have regular mammograms in the future | 78.8 | 86.7 | 59.2 | 59.6 | 25.2 | 30.1 |

| No recollection of discussion with doctor that mammography may no longer be necessary | 94.1 | 93.6 | 81.4 | 82.9 | 71.6 | 71.6 |

| Prostate cancer screening | N = 229 | N = 912 | N = 269 | N = 105 | N = 119 | N = 0 |

| Self-report PSA screen within the last 2 years | 59.4 | 61.4 | 65.9 | 74.4 | 46.5 | – |

| Plan to have regular PSA screens in the future | 67.9 | 72.3 | 54.1 | 67.0 | 31.1 | – |

| No recollection of discussion with doctor that PSA screens may no longer be necessary | 95.4 | 92.5 | 76.5 | 79.8 | 78.2 | – |

Life expectancy is estimated based on the Lee prognostic index26

LE remaining life expectancy, PSA prostate-specific antigen

Table 4 shows rates of future intentions to pursue screening stratified by recent screening and discussions with doctors on whether screening is necessary. Notably, among individuals who had a discussion with their doctor that they may not need regular mammograms or regular PSA tests, approximately 41% and 39% still plan to have regular screening in the future, respectively.

Table 4.

Future Plans to Receive Cancer Screening

| Variables | Do you plan to have regular screening in the future | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | “I do what my doctor says” | |

| Breast cancer screening | |||

| How long since you had a mammogram? | |||

| Within the last 2 years (%) | 89.3 | 4.7 | 5.9 |

| > 2 years ago or never (%) | 46.4 | 44.7 | 8.9 |

| Has a doctor ever suggested that you may no longer need regular mammograms? | |||

| Yes (%) | 40.6 | 41.2 | 18.2 |

| No (%) | 83.4 | 12.1 | 5.5 |

| Prostate cancer screening | |||

| How long since you had a PSA test? | |||

| Within the last 2 years (%) | 83.0 | 5.6 | 11.4 |

| > 2 years ago or never (%) | 46.4 | 38.1 | 15.5 |

| Has a doctor ever suggested that you may no longer need regular PSA tests? | |||

| Yes (%) | 39.3 | 43.5 | 17.2 |

| No (%) | 72.8 | 15.1 | 12.1 |

PSA prostate-specific antigen

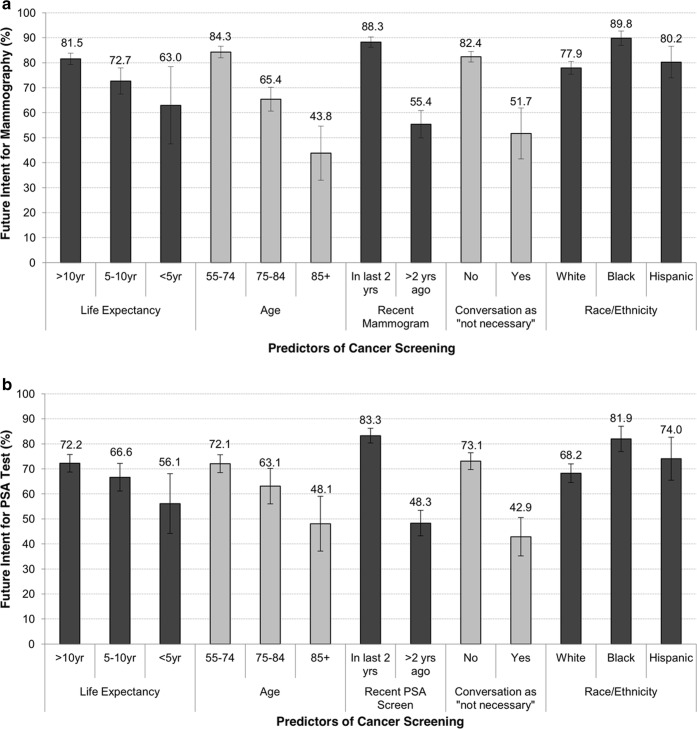

We used multivariate logistic regression models to determine individual characteristics associated with intentions to pursue cancer screening. We present the adjusted marginal probabilities of intention to pursue future mammography and PSA tests in Fig. 1a and b, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Women had a higher intentions to have future mammograms if they reported receiving a recent mammogram (88% vs 55%, OR = 8.25, 95% CI 5.79–11.75) or no conversations with a doctor that screening may not be necessary (82% vs 52%, OR = 7.05, 95% CI 4.00–12.45). Older age was associated with reduced intentions to receive future mammography (84% in age 55–74 vs 44% in age 85+, OR = 0.07, 95% CI 0.04–0.13), as was reduced life expectancy (82% in LE > 10 years vs 73% in LE 5–10 years, OR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.34–0.73). Black women had higher odds of intending to have future mammograms than white women (90% vs 78%, OR = 3.53, 95% CI 2.26–5.52).

Figure 1.

Adjusted marginal probabilities for future intention to receive. a Mammography or b PSA tests according to key predictors: life expectancy, age, recent screening, recent conversation with a doctor that screening is “not necessary,” and race/ethnicity. Model adjusts for age, self-reported recent screen, no prior discussion that screening may “not be necessary,” ethnicity/race, education, marital status, the modified Lee prognostic index, cognition, and depressive symptoms. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Men had higher odds of wanting future PSA tests if they had a recent PSA test (83% vs 48%, OR = 6.26, 95% CI 4.75–8.26) or had no conversation that PSA testing may no longer be necessary (73% vs 43%, OR = 4.97, 95% CI 3.29–7.49). Older age was associated with reduced future intentions to be screened (72% in age 55–74 versus 48% in age 85+, OR = 0.27, 95% CI 0.15–0.48), as was reduced life expectancy (72% in LE > 10 years vs 67% in LE 5–10 years, OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.55–0.94). Similar to mammography in women, black men had higher odds of intending future PSA tests compared to white men (82% vs 68%, OR = 2.55, 95% CI 1.62–4.02).

DISCUSSION

In a large, nationally representative sample of older adults in the USA, including subsets who have a life expectancy of less than 10 years, we found that more than half of women and men age 75–84 years old and a third of individuals 85 years or older with less than a 10-year life expectancy are interested in receiving regular mammograms or PSA tests in the future. In addition, over 75% of these individuals do not recall having a conversation with a doctor suggesting they may no longer need screening. Findings indicate a high self-reported rate of PSA testing and mammograms among older adults with limited life expectancy despite national guidelines, suggesting additional strategies are needed to reduce overscreening in older adults.

Our study shows substantial enthusiasm to pursue future mammography and PSA screening among older adults with limited life expectancy. This is consistent with prior studies in younger, healthier adults, which show they tend to overestimate the benefits and underestimate the potential harms.16,18,35 This enthusiasm does not match national guidelines. For mammography, the USPSTF notes insufficient evidence (grade C) to continue after age 75, and 2018 American Cancer Society guidelines recommend screening for those > 55 only when having a life expectancy > 10 years.7 For PSA screening, multiple organizations have consistently recommended against screening in men > 70 years old or those with < 10-year life expectancy. Therefore, a relatively consistent message to reduce overscreening in older adults with limited life expectancy by multiple national organizations does not seem to have reached patients.

On the contrary, individuals with recent screening seem intent on continuing; after adjustment for age and life expectancy, women with recent mammograms had over eight times the odds of future plans for mammography and men with recent PSA tests had six times the odds of such future plans. This is consistent with qualitative studies where older adults often view screening as “morally obligatory” and the decision to stop as a major change.19,20 Indeed, our results indicate that even when some individuals recall a discussion about stopping screening with their doctor, 40% still desire future screening.

On the other hand, many individuals rely on physicians to guide their treatment choices, especially at older ages.36,37 Study results are the first to show that among women over 75 years old, over 75% of those with limited life expectancy had no recollection of any conversation with a doctor that mammography may no longer be appropriate. This was similarly the case for men with PSA screening, despite the heightened awareness of the lack of demonstrated benefit among older men in large randomized trials for nearly a decade.8,38 Individuals who recalled a conversation with a doctor that screening may no longer be needed had five times lower odds of intending to seek future screening. Although our data is limited to patient recollections, results suggest physicians may be missing or unable to take opportunities to guide patients away from overscreening. These discussions can be time-consuming and perceived as negative or “taking away” a test viewed as beneficial, prompting many physicians to avoid the topic altogether. Indeed, one study on PSA screening showed low rates of shared decision-making in 2005 and 2010,14 and that healthcare providers tend to discuss the pros of screening more often than the cons.39

Notably, black women and men had more than twice the odds of future intentions to pursue mammography or PSA screening compared to white women and men, even after adjusting for age and life expectancy. Results are consistent with prior qualitative work showing black individuals have positive attitudes towards cancer screening.40–42 Future work is needed to confirm this finding and determine if considerations of race/ethnicity should be incorporated into efforts to reduce overscreening.

We suggest the approach to reducing overscreening in older adults focus less on “stopping screening” which prior research suggests can be less productive,20,43 and more on “tailoring” preventive activities to the individual person. In effect, providers would re-direct enthusiasm for cancer screening towards interventions with greater evidence of a shorter lag-time to benefit. Several communication strategies exist to aid in this effort. For example, providers can use the phrase “the test would not help you live longer” to incorporate life expectancy considerations rather than “you may not live long enough to benefit from this test.”43 Patient-centered decision aids for PSA tests and mammography have been developed.44–46 Since calculations of life expectancy can be a barrier to discussions on stopping screening, cancer screening-specific tools are available online (www.ePrognosis.org) to clinicians to incorporate life expectancy into easily interpreted images for individuals to view during the office visit.47–51 Notably, clinicians should be aware that if they use age as a marker of life expectancy, the median life expectancy at age 75 for men and at age 80 for women is close to 10 years.47,50 Therefore, especially at these ages and above, providers should use clinical judgment about the number and severity of comorbid conditions or life expectancy tools to adjust estimates of the benefit of screening up or down. Finally, to complement endeavors by primary care providers, future studies could explore if efforts from specialists like gynecologists, radiologists, and urologists, or public health campaigns directed at patients might take advantage of opportunities to re-direct individuals away from screening and towards other preventive health interventions.52

Our study has several limitations. First, data is self-reported, without medical record review, and may not fully reflect the actual screening rates or content of discussions with physicians.53,54 We do note that screening rates reported in our study are similar to those estimated from NHIS data.11,15 In addition, self-reported data provides information on individuals perceptions of what conversations have occurred and intentions to pursue future screening. Second, the NSHAP survey does not include information on the source of care or clinician characteristics, so we cannot, for example, comment on whether primary care providers or specialists are involved in different types of conversations with respondents. Third, while the Lee index is strongly predictive of mortality in older adults, it is not completely accurate in its estimates for specific individuals. However, it is a practical tool, given its use of common clinical variables, user-friendly availability online, and strong associations with mortality within the NSHAP cohort (Table 1). Fourth, data is cross-sectional which limits our ability to make causal claims. Fifth, our results are only generalizable to community-dwelling older adults in the USA and how it applies in other populations is not known.

In conclusion, in a nationally representative sample, many older adults with limited life expectancy have future plans to continue screening, and approximately 75% of these individuals recall no prior discussion with a doctor that screening may no longer be needed. Our findings show an opportunity for health care providers to tailor preventive care to individuals so that they receive the care that is most likely to help them and least likely to harm them. Based on these findings, we recommend involving public health officials, quality improvement interventions, and medical specialists in addition to primary care providers in the efforts to reduce overscreening and promote patient-centered decision-making for preventive health interventions.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 18 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) who were responsible for data collection. The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project is supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health (R01AG043538; R01AG048511; R37AG030481). Dr. Louise Walter’s effort on this project was supported by a K24 Midcareer Mentoring Award for Patient-Oriented Research in Aging (K24AG041180) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Sei Lee was supported by R01 AG0477897 from the National Institute on Aging and IIR 15-434 from VA HSR&D.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All respondents provided written informed consent and the protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Chicago and National Opinion Research Center (NORC).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2027–2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko CW, Sonnenberg A. Comparing risks and benefits of colorectal cancer screening in elderly patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(4):1163–1170. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarfield AM. Screening in frail older people: an ounce of prevention or a pound of trouble? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):2016–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siu AL. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith RA, Andrews K, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2016: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.USPSTF. Prostate Cancer Screening Draft Recommendations. 2017; https://screeningforprostatecancer.org/. Accessed 4-27-2017.

- 9.Carter HB. American Urological Association (AUA) guideline on prostate cancer detection: process and rationale. BJU Int. 2013;112(5):543–547. doi: 10.1111/bju.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SGIM. Choosing Wisely: Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. 2019; http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/society-of-general-internal-medicine/. Accessed 2-6-2019.

- 11.Schonberg MA, Breslau ES, McCarthy EP. Targeting of mammography screening according to life expectancy in women aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):388–395. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter LC, Bertenthal D, Lindquist K, Konety BR. PSA screening among elderly men with limited life expectancies. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2336–2342. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotwal AA, Mohile SG, Dale W. Remaining life expectancy measurement and PSA screening of older men. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3(3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drazer MW, Prasad SM, Huo D, et al. National trends in prostate cancer screening among older American men with limited 9-year life expectancies: Evidence of an increased need for shared decision making. Cancer. 2014;120(10):1491–1498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drazer MW, Huo D, Eggener SE. National prostate cancer screening rates after the 2012 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation discouraging prostate-specific antigen–based screening. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(22):2416–2423. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(1):71–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–286. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gigerenzer G, Mata J, Frank R. Public knowledge of benefits of breast and prostate cancer screening in Europe. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(17):1216–1220. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torke AM, Schwartz PH, Holtz LR, Montz K, Sachs GA. Older adults and forgoing cancer screening:“I think it would be strange”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):526–531. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schonberg MA, Ramanan RA, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. Decision making and counseling around mammography screening for women aged 80 or older. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):979–985. doi: 10.1007/BF02743148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NORC. National Social life Health and Aging Project. 2018; http://www.norc.org/Research/Projects/Pages/national-social-life-health-and-aging-project.aspx. Accessed 2-6-2019.

- 22.O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, Kwok PK. Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for wave 2 of the NSHAP. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 2):S15–S26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caplan LS, Mandelson MT, Anderson LA. Validity of self-reported mammography: examining recall and covariates among older women in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(3):267–272. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall HI, Van Den Eeden SK, Tolsma DD, et al. Testing for prostate and colorectal cancer: comparison of self-report and medical record audit. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruz M, Covinsky K, Widera EW, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Lee SJ. Predicting 10-year mortality for older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(9):874–876. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295(7):801–808. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drazer MW, Huo D, Schonberg MA, Razmaria A, Eggener SE. Population-based patterns and predictors of prostate-specific antigen screening among older men in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1736. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'malley MS, Earp JA, Hawley ST, Schell MJ, Mathews HF, Mitchell J. The association of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and physician recommendation for mammography: who gets the message about breast cancer screening? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):49. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calle EE, Flanders WD, Thun MJ, Martin LM. Demographic predictors of mammography and Pap smear screening in US women. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(1):53–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.83.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasilopoulos T, Kotwal A, Huisingh-Scheetz MJ, Waite LJ, McClintock MK, Dale W. Comorbidity and chronic conditions in the national social life, health and aging project (NSHAP), Wave 2. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 2):S154–S165. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne C, Hedberg E, Kozloski M, Dale W, McClintock MK. Using and interpreting mental health measures in the national social life, health, and aging project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 2):S99–S116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shega JW, Sunkara PD, Kotwal A, et al. Measuring cognition: the chicago cognitive function measure in the national social life, health and aging project, wave 2. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(S2):S166–S176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kotwal AA, Schumm LP, Kern DW, et al. Evaluation of a brief survey instrument for assessing subtle differences in cognitive function among older adults. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(4):317. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011.

- 35.Yu J, Nagler RH, Fowler EF, Kerlikowske K, Gollust SE. Women’s awareness and perceived importance of the harms and benefits of mammography screening: Results from a 2016 national survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1381–1382. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffman RM, Lewis CL, Pignone MP, et al. Decision-making processes for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30(5_suppl):53–64. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10378701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo F, He D. The roles of providers and patients in the overuse of prostate-specific antigen screening in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):650–651. doi: 10.7326/L15-5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Hoffman RM, Elmore JG, Fairfield KM, Gerstein BS, Levin CA, Pignone MP. Lack of shared decision making in cancer screening discussions. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3):251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greiner KA, Born W, Nollen N, Ahluwalia JS. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):977–983. doi: 10.1007/s11606-005-0244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandzel S, Chang E, Tuzzio L, et al. Latina and black/African American women’s perspectives on cancer screening and cancer screening reminders. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(5):1000–1008. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFall SL, Hamm RM, Volk RJ. Exploring beliefs about prostate cancer and early detection in men and women of three ethnic groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1121–1128. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor KL, Williams RM, Davis K, et al. Decision making in prostate cancer screening using decision aids vs usual care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1704–1712. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barry MJ, Wexler RM, Brackett CD, et al. Responses to a decision aid on prostate cancer screening in primary care practices. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schonberg MA, Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid on mammography screening for women 75 years and older. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):417–424. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1336–1347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CDC. United States Life Tables, 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2012;65(8). [PubMed]

- 50.Kotwal AA, Schonberg MA. Cancer screening in the elderly: a review of breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer screening. Cancer J. 2017;23(4):246–253. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.August KJ, Sorkin DH. Marital status and gender differences in managing a chronic illness: The function of health-related social control. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(10):1831–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radhakrishnan A, Nowak SA, Parker AM, Visvanathan K, Pollack CE. Physician breast cancer screening recommendations following guideline changes: results of a national survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):877–878. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan E, Vernon S, Ahn C, Greisinger A. Do men know that they have had a prostate-specific antigen test? Accuracy of self-reports of testing at 2 sites. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1336–1338. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer-screening histories: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17(4):748–757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 18 kb)