Abstract

Background

The gap between treatment guidelines and clinical practice in prediabetes management has been identified in previous studies. The knowledge related to addressing lifestyle change during office visits in clinical practice to manage prediabetes is limited.

Objective

To describe patterns of lifestyle management addressed during office-based visits involving patients with prediabetes and identify factors associated with addressing lifestyle management during physician office visits in the USA.

Design

Cross-sectional study

Participants

US National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) data from 2013 to 2015 were combined to identify office-based visits involving patients with prediabetes.

Main Measures

The major outcome is lifestyle management including diet/nutrition, exercise, and/or weight reduction. Patient and physician characteristics were collected for analysis. The prevalence and patterns of addressing lifestyle management during visits were estimated and described. Multivariate logistic regression model identified significant factors associated with lifestyle management. The patient visit weight was applied to all analyses to achieve nationally representative estimates.

Key Results

Among 4039 office-based visits involving patients with prediabetes between 2013 and 2015, 22.8% indicated lifestyle management was addressed during the visits. Diet/nutrition, exercise, and weight reduction accounted for 86.1%, 62.6%, and 34.1% of the visits with lifestyle management addressed, respectively. Lifestyle management was more likely to be addressed during the visits involving patients with hyperlipidemia (OR = 1.74, 95% CI 1.24–2.46) and obesity (OR = 4.03, 95% CI 2.91–5.56), seeing primary physicians (vs. other specialties, OR = 1.46, 95% CI 1.03–2.08), and living in the southern region (vs. northeast, OR = 1.96, 95% CI 1.20–3.19).

Conclusions

The prevalence of addressing lifestyle management during office visits involving patients with prediabetes remained low in the USA. Patients’ clinical characteristics, geographic region, and physician’s specialty were associated with addressing lifestyle management during the visits.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4724-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: prediabetes, diabetes, disease management, patient education

INTRODUCTION

People with prediabetes are at high risk to develop type 2 diabetes.1, 2 In the USA, 33.9% of adults (84.1 million) had prediabetes in 2015.3 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) clinical guidelines recommend lifestyle change as a primary intervention to prevent or delay the progression to type 2 diabetes.4–6 Evidence demonstrates that lifestyle modification, including diet, exercise, and weight reduction, is effective in lowering the risk for type 2 diabetes.7, 8 Moreover, a combination of diet and exercise has been shown to be more effective than either alone to reduce diabetes incidence.9

The knowledge related to lifestyle management education delivered during office visits in clinical practice to manage prediabetes as recommended by guidelines is limited. Besides focusing on the effectiveness of lifestyle management in randomized controlled trials, few studies examine the prevalence and patterns of the use of lifestyle management in patients with prediabetes in clinical practice.10, 11 A gap between treatment guidelines and clinical practice has been demonstrated through several studies assessing metformin use patterns in various populations with prediabetes where the prevalence of metformin use for prediabetes remains low in US population (1–8%)12–14 despite being recommended by the ADA guidelines.6 Engaging patients in lifestyle change has been a challenge in prediabetes management. Physician advice plays an important role in influencing patient motivation for behavior change and improving patient adherence to lifestyle changes.10, 11, 15 Understanding the patterns of lifestyle management delivery in prediabetes can help identify the gap between guidelines and clinical practice and provide implications to develop and tailor effective intervention programs to improve health outcomes.

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) data from 2013 to 2015 was analyzed in this study to examine the lifestyle management addressed during office visits involving patients with prediabetes in the USA as reported by health care providers. The objectives of this study were (1) to describe patterns of addressing lifestyle management during office visits and (2) to identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with addressing lifestyle management during office visits. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Presbyterian College.

METHODS

Data Source

NAMCS is a national two-stage sample survey of visits to non-federally employed, office-based physicians in the USA. The physicians are selected in the first stage, and a reporting week is randomly assigned to physicians in the second stage to report all visits during the week.16 The national survey is conducted and administered annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The sample visits collect patient demographics, reasons and diagnoses for the visits, sources of payments, services provided (lab tests, procedures, examinations, treatments, health educations, etc.), comorbidities, and medications prescribed. In addition, the survey collects providers’ and practice sites’ information. Weights are assigned to the sample visits to obtain national estimates.

Selection of Prediabetes-Related Visits

The combined 3 years of NAMCS data (2013–2015) yielded samples of the office visits associated with prediabetes. The study sample consisted of visits involving prediabetes patients as identified by using most recent A1C (5.7–6.4%), fasting blood glucose (100–125 mg/dL), or ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (790.21, 790.22, or 790.29) to reflect impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or other abnormal glucose levels. However, from 2015, the lab test results were removed from the NAMCS data due to low response rate. Consequently, the eligible visits in 2015 were identified by using ICD-9 diagnosis codes only. NAMCS measured comorbid chronic conditions including diabetes by asking, “Regardless of the diagnoses written above, does the patient now have (disease)?” The providers used a checkbox to report nearly 20 chronic conditions in NAMCS. Patients with concurrent diagnosis codes for diabetes (250) or reporting pregnancy or diabetes as a comorbid chronic condition were excluded.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The following demographic measurements were included in the analysis: age, sex, ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other), and primary source of payment for the visit (private insurance, Medicare/Medicaid, and other). The clinical characteristics include diabetes-related comorbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity) and a total number of chronic conditions reported directly as a category within the data set. In addition, physician specialty (primary care or not) and office location (metropolitan statistical area or not) were included in the analysis.

Outcome Measures

NAMCS measured health education/counseling provided at the visits as well as orders or referrals for education/counseling for various conditions. No further details were provided to differentiate or define the services provided, ordered, and referred. Thus, the major outcome in this study was defined as addressing lifestyle management during office visits. For prediabetes, three variables, including diet/nutrition, exercise, and/or weight reduction, were available to reflect the type of lifestyle management. This study defines that lifestyle management was addressed if at least one of the three above health educations was mentioned during the visits involving patients with prediabetes. A secondary outcome reviewed metformin prescribing at the visits as identified by using the Multum classification of therapeutic classes developed by the Lexicon Plus database.

Sensitivity Analysis

Considering underrepresented sample visits from 2015 as a result of the use of ICD-9 codes only, the characteristics of the study samples from 2013 to 2014 vs. 2015 were compared. The prevalence of lifestyle management was compared between the samples from 2013 to 2014 and from 2015.

Data Analysis

The prevalence and patterns of addressing lifestyle management during the visits involving patients with prediabetes were described by relative frequencies. Chi-square tests compared the demographic and clinical characteristics between those visits with lifestyle management and not. Logistic regression identified significant factors associated with addressing lifestyle management during the office visits. The statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05. The patient visit weight was applied to all analyses to achieve nationally representative estimates.

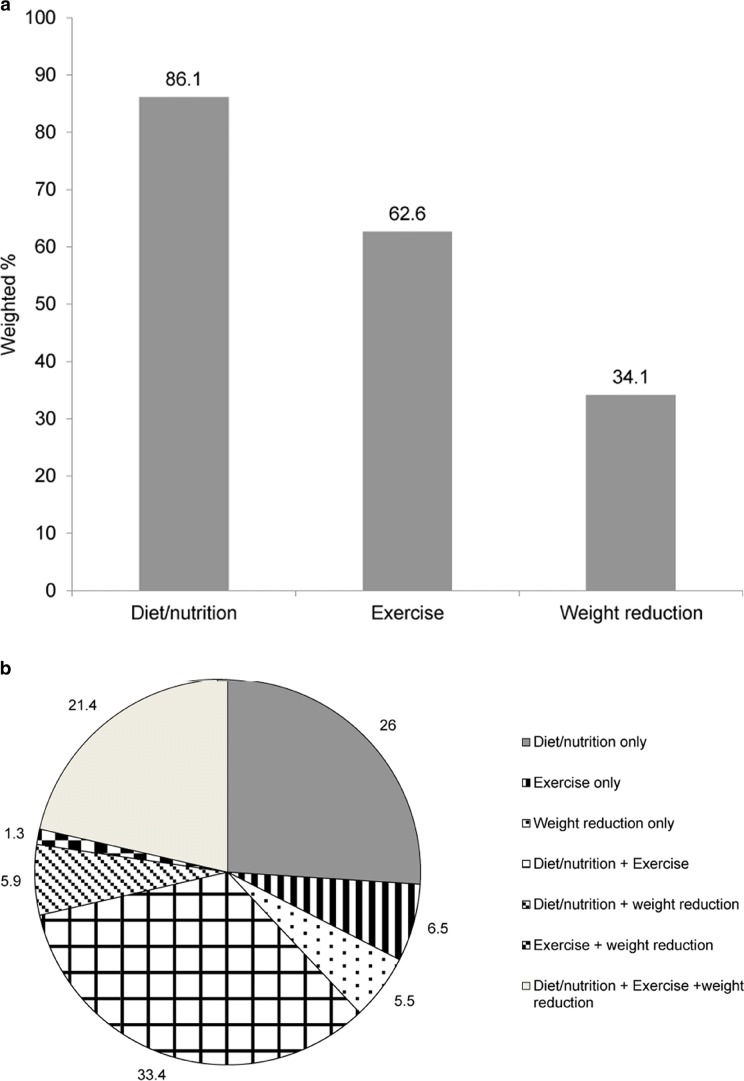

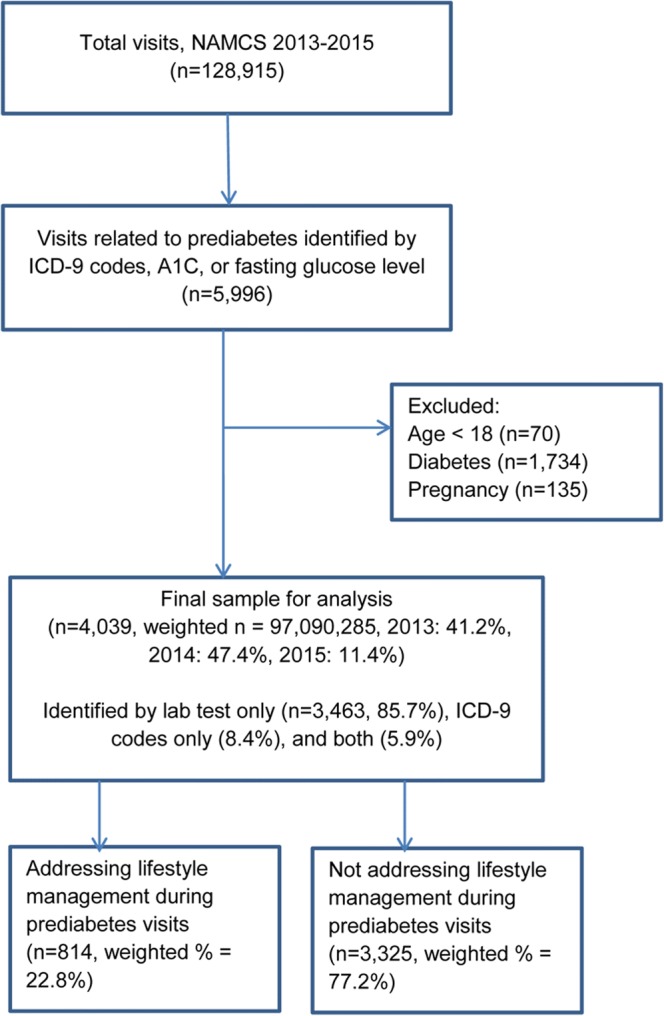

RESULTS

From 2013 to 2015, an estimated 4039 office-based visits involving patients with prediabetes were identified, representing estimated 97 million prediabetes office-based visits in the USA (Fig. 1). Of those, 91.6% were identified by lab tests (A1C or fasting glucose levels). In the study sample, the lifestyle management (diet/nutrition, exercise, or weight reduction) was addressed at 22.8% of the total visits with people having prediabetes, representing 22.6 million visits in the USA from 2013 to 2015. Diet/nutrition, exercise, and weight reduction were addressed at 86.1%, 62.1%, and 34.1% of those visits reporting lifestyle management, respectively (Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows that 38% of the visits addressing lifestyle management involved only one of the above three education services. In addition, 40.6% and 21.4% of the visits involved two or all three education services, respectively.

Figure 1.

Analysis sample.

Figure 2.

Patterns of addressing lifestyle management during visits involving patients with prediabetes, NAMCS 2013–2015 ( n = 814, weighted n = 22,166,419). a Overall distribution of lifestyle management. b Combination of individual lifestyle management service.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the office-based visits involving patients with prediabetes. The visits addressing lifestyle management (vs. not) were more likely to involve primary care physicians (80% vs. 71.5%) and patients who were younger than 65 years (59.2% vs. 50.8%), obese (51.1% vs. 30.6%), non-Hispanic Black (16.2% vs. 9.3%), from the southern region (42.7% vs. 28.1%), or with comorbid hyperlipidemia (56.9% vs. 46.2%). The proportions of metformin prescribing during the visits were similar between the lifestyle management group and not (3.1% vs. 2.0%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Visits Involving Patients with Prediabetes by Lifestyle Management, NAMCS 2013–2015 (n = 4039, Weighted n = 97,090,285)

| Variable | Lifestyle management (n = 814, weighted n = 22,166,419) | No lifestyle management (n = 3325, weighted n = 74,923,685) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (weighted %) | n (weighted %) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.04 | ||

| 18–44 | 112 (18.5) | 385 (11.7) | |

| 45–64 | 371 (40.6) | 1268 (39.1) | |

| ≥ 65 | 331 (40.8) | 1572 (49.2) | |

| BMI | < 0.001 | ||

| Underweight | 140 (14.8) | 770 (23.2) | |

| Normal | 103 (11.7) | 568 (18.8) | |

| Overweight | 197 (22.4) | 834 (27.4) | |

| Obesity | 374 (51.1) | 1053 (30.6) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.03 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 609 (63.4) | 2579 (73.0) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 78 (16.2) | 238 (9.3) | |

| Hispanic | 77 (14.7) | 238 (11.3) | |

| Other | 50 (5.6) | 170 (6.5) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 436 (56.8) | 1720 (52.4) | 0.21 |

| Primary payer | 0.29 | ||

| Private | 406 (47.0) | 1351 (43.3) | |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 337 (43.4) | 1587 (49.0) | |

| Uninsured/other | 71 (9.6) | 287 (7.7) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 442 (56.9) | 1357 (46.2) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 499 (60.3) | 1730 (55.4) | 0.26 |

| Total number of chronic conditions | 0.06 | ||

| 0 | 78 (10.2) | 472 (13.9) | |

| 1 | 173 (23.4) | 784 (25.9) | |

| 2 | 233 (29.0) | 902 (29.0) | |

| ≥ 3 | 330 (41.0) | 1067 (31.5) | |

| Metformin prescribed | 29 (3.1) | 73 (2.0) | 0.13 |

| Physician characteristics | |||

| Primary care | 578 (80.0) | 2045 (71.5) | 0.008 |

| Metropolitan area* | 739 (94.7) | 2845 (91.9) | 0.07 |

| Region† | 0.003 | ||

| Northeast | 114 (16.7) | 457 (21.2) | |

| Midwest | 247 (16.0) | 1012 (21.2) | |

| South | 249 (42.7) | 848 (28.1) | |

| West | 204 (24.8) | 908 (29.6) | |

BMI body mass index, NAMCS National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

*Based on physician location by metropolitan statistical area

†Based on location where majority of visits records were sampled

In the logistic regression model (Table 2), ethnicity, sex, health insurance, and location of physician office did not influence the likelihood of addressing lifestyle management during the visits. However, the visits involving patients with comorbid hyperlipidemia and obesity were 74% and four times more likely to address lifestyle management than those not, respectively. The likelihood of addressing lifestyle management were 46% higher in patients seeing a primary care physician as compared to a specialist and 96% higher if living in the southern region compared to the northeast.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Addressing Lifestyle Management During Visits Involving Patients with Prediabetes, NAMCS 2013–2015 (n = 4039, Weighted n = 97,090,285)

| Independent variable | Odds ratio of lifestyle management (95% confidence interval) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–44 | 1.00 | |

| 45–64 | 0.66 (0.40, 1.09) | 0.10 |

| ≥ 65 | 0.56 (0.33, 0.94) | 0.03 |

| Race | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.00 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.26 (0.72, 2.19) | 0.42 |

| Hispanic | 1.25 (0.69, 2.25) | 0.46 |

| Other | 1.13 (0.87, 1.47) | 0.46 |

| Sex | ||

| Male (vs. female) | 0.87 (0.67, 1.13) | 0.29 |

| Primary payer | ||

| Private insurance | 1.00 | |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 0.89 (0.64, 1.23) | 0.47 |

| Uninsured/other | 1.04 (0.68, 1.61) | 0.85 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Hyperlipidemia (vs. no) | 1.74 (1.24, 2.44) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension (vs. no) | 1.36 (1.00, 1.86) | 0.05 |

| Obesity (vs. no) | 4.03 (2.91, 5.56) | < 0.001 |

| Number of chronic conditions | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 0.75 (0.46, 1.23) | 0.24 |

| 2 | 0.63 (0.37, 1.07) | 0.08 |

| ≥ 3 | 0.65 (0.36, 1.18) | 0.15 |

| Physician characteristics | ||

| Primary care (vs. no) | 1.46 (1.03, 2.08) | 0.03 |

| Metropolitan area* (vs. no) | 0.66 (0.39, 1.11) | 0.10 |

| Region† | ||

| Northeast | 1.00 | |

| Midwest | 1.10 (0.69, 1.77) | 0.75 |

| South | 1.96 (1.20, 3.19) | 0.007 |

| West | 1.03 (0.62, 1.72) | 0.88 |

NAMCS National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

*Based on physician location by metropolitan statistical area

†Based on location where majority of visits records were sampled

Appendix 1 in ESM 1 displays the results from sensitivity analysis. Nearly 11.4% of the visits were from 2015 sample. Except distribution of ethnicity and hyperlipidemia, similar characteristics were found between the samples from 2013 to 2014 and from 2015. The prevalence of addressing lifestyle management based on the 2013–2014 study sample was 21.3%, which is 1.5% lower than the result based on the 2013–2015 sample.

DISCUSSION

Using nationally representative data from NAMCS (2013–2015), we found that the prevalence of addressing lifestyle management during office-based visits involving US adults with prediabetes remains lower than 25% in US adults. Initiating lifestyle modification is the primary intervention to prevent the occurrence of diabetes and is recommended by guidelines with level A evidence, along with metformin treatment, to prevent type 2 diabetes.6 This study identified a gap in translating the clinical evidence supporting lifestyle management to prevent or delay progression to diabetes into real-world practice.

The low prevalence of addressing lifestyle management during office-based visits raises the need to improve disease management in patients with prediabetes. Health care providers are the primary source for the patients to manage the disease. Nearly 60% of diabetes patients learned diabetes care from health care professionals, and the remaining 40% learned from the combination of health professionals and other sources (e.g., Internet or group classes).17

In this study, although the study sample was not selected by the inclusion criteria for metformin use, only 2.5% of the patients were prescribed metformin during the visits related to prediabetes. The proportions of the visits with metformin prescribed were similar between those providing lifestyle management (3.1%) and not (2.0%). It is worth noting that the low prevalence of medication use to treat prediabetes was also observed in other recent studies. For example, the prevalence of metformin use to prevent type 2 diabetes remained low, ranging from 0.7 to 7.4% in various populations with prediabetes.12–14 More efforts are needed to reduce the gap between the guideline recommendations and what is implemented in practice in prediabetes management.

The results from the regression model suggested that lifestyle management was more likely to be addressed during the visits involving patients with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or obesity. However, it is not clear whether the lifestyle management addressed during the visits specifically targeted the comorbidities or prediabetes. Prediabetes patients with comorbid hypertension, abnormal lipid profile, and obesity have a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.1, 18, 19 Lifestyle management has favorable effects to prevent the onset of both diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Due to the high prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity in patients with prediabetes, the treatment guidelines suggest managing the comorbidities.20, 21 This study suggested that physicians tended to deliver prediabetes management to higher-risk populations. On the other hand, it also showed that patients with obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were involved in 30.6%, 55.4%, and 46.2% of the prediabetes visits, respectively, without lifestyle management provided (Table 1). The results suggested that many prediabetes patients with diabetes-related comorbidities did not receive adequate disease management during office visits.

This study indicated that 80% of the visits addressing lifestyle management occurred at primary care sites and primary care physicians were 46% more likely to do so than other specialties. Primary care is the major source for the patients to learn disease self-management. The Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes calls for all providers to use a patient-centered approach to optimize diabetes management and improve health outcomes.22 The chronic care model in the primary care settings integrates health system, self-management support, decision support, delivery system design, clinical information system, and community resources and policies into a well-rounded and effective framework to improve the quality of diabetes care.23 However, more evidence is needed to determine how to better implement efficacious lifestyle interventions into diabetes prevention in primary care in real-world settings using the chronic care model.

Although this study did not find disparities of lifestyle management in demographics, such as gender, race, and location of the physician offices, the geographic variation among the office visits involving patients with prediabetes showed that lifestyle management was more likely to be addressed in the southern region than other regions. The southern region accounted for more than 40% of visits with lifestyle management. Moreover, visits in the south were almost two times more likely to address lifestyle management than those in the northeast. The relatively higher prevalence of diabetes in the Southern United States might contribute to the highest proportion of lifestyle management during prediabetes visits. Twelve of 16 southern states had prevalence rates of prediabetes above the national average of 9.7% in 2015. However, the prediabetes prevalence in most states in other regions was lower than 9.7%.24 The higher diabetes prevalence in this region might make providers more likely to address lifestyle management to those at high risk of developing diabetes compared to other regions where these risks are less frequent.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results from NAMCS data. First, the study sample in the analysis represents the event-level health care utilization involving patients with prediabetes. The results in this study may not reflect the accurate characteristics of the population with prediabetes and how individual patients receive the lifestyle management to prevent diabetes since identification of data for inclusion is dependent on documentation from patient encounters as opposed to being dependent on patient-specific data. Thus, the prevalence of lifestyle management in our study cannot be translated to population-based prevalence. The lack of details provided in the database to distinguish or describe the services provided, ordered, and referred at the visits does not allow for the type or extent of the intervention to be determined. Moreover, many patients had diabetes-related comorbidities resulting in the possibility that the lifestyle management could have been targeted towards the management of the comorbid conditions instead of prediabetes. An assumption of lifestyle management for prediabetes was made in the study. Second, the events were reported by practitioners who participated in the survey voluntary. The variation of the visit frequency based on patient- and practitioner-specific factors might influence the representativeness of the study sample and results. For example, patients with a greater number of chronic conditions or severe diseases are more likely to visit their doctors frequently, which could overrepresent the study sample or, alternatively, underrepresent the sample if lifestyle interventions were provided at previous visits but not readdressed and captured during the survey period. The event-level NAMCS data with a cross-sectional design only reflects a snapshot of health education provided at the visits and did not capture separate visits with the same patients during the assigned reporting week. Visits could have focused on more acute or severe conditions without need for lifestyle management over the management of prediabetes but would have, nonetheless, been represented in the study sample. Additionally, providers might have discussed the lifestyle modification but failed to mention it in their documentation. Recall bias and reporting bias should be considered when interpreting the results. Finally, in 2015, the lab test results were removed from the NAMCS data due to low response rate. The visits with people having prediabetes in 2015 were identified by using ICD-9 diagnosis codes only. The visits included in the analysis sample from 2015 data might underrepresent the visits involving patients with prediabetes in 2015. The sensitivity analysis indicated a higher proportion of patients with hyperlipidemia in the group receiving lifestyle management education which could be attributed to the presence of this comorbid condition. Also, antidiabetic medication use was not incorporated into the exclusion criteria to identify patients with diabetes since these agents can be used to manage prediabetes. Misclassification of diabetes was minimized by using diabetes ICD-9 codes for the visits and comorbid diabetes reported by providers at the visits.

Despite the limitations of the study, our findings provide important implications to health care providers. First, lifestyle management is the foundation to prevent or delay progression from prediabetes to diabetes. The low prevalence of addressing lifestyle management during office visits involving patients with prediabetes implied a gap between clinical guideline and real-world practice in physician office visits. Health care providers should take advantage of the opportunity to educate those with prediabetes about the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and how this can be prevented or delayed with proper lifestyle changes as patients aware of their prediabetes condition and its risks through provider intervention are more likely to engage in lifestyle management activities.25 The uptake and sustained adherence to lifestyle changes is poor in patients with prediabetes.25 Provider education on the disease state and lifestyle changes is vital but must be coupled with acknowledgement and consideration of patients’ various stages of change and psychosocial issues that may impact patient behavior when offering lifestyle management interventions and will likely require a patient-centered, multi-disciplined approach to be effective.26 Second, health care providers are more likely to provide lifestyle management during the visits involving patients with comorbidities associated with diabetes, such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obesity. However, due to the low prevalence of lifestyle management provided during prediabetes-related visits, a large proportion of high-risk patients did not obtain adequate treatment. With the strong evidence from diabetes prevention programs, practitioners are encouraged to capture all opportunities to deliver adequate health education in all clinical encounters related to prediabetes. Finally, clinical guidelines emphasize patient-centered approach in diabetes care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have established the Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program to encourage lifestyle management education into office visits to reduce diabetes incidence.27 Further studies are needed to assess the quality of lifestyle management counseling provided during outpatient visits and associated health outcomes of such discussions. This could lead to discoveries on how to tailor lifestyle intervention by targeting individual patients and weight issues, how to screen for prediabetes, and how to engage patients in the intervention programs in the hopes of ultimately improving health care costs, morbidity, and mortality associated with diabetes.28–30

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 21 kb)

Authors’ Contributions

There are no contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S13–27. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M. Prediabetes: A high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379:2279–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2018.

- 4.Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group The diabetes prevention program (DPP): Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–71. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: A 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1783–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association 5. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S51–4. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: Follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006;368:1673–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haw JS, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, et al. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1808–17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balk EM, Earley A, Raman G, Avendano EA, Pittas AG, Remington PL. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: A systematic review for the community preventive services task force. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:437–51. doi: 10.7326/M15-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsey R, Songer T. Lifestyle behaviors and physician advice for change among overweight and obese adults with prediabetes and diabetes in the United States, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang K, Lee Y, Chasens ER. Outcomes of health care providers’ recommendations for healthy lifestyle among US adults with prediabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9:231–7. doi: 10.1089/met.2010.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moin T, Li J, Duru OK, et al. Metformin prescription for insured adults with prediabetes from 2010 to 2012: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:542–8. doi: 10.7326/M14-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseng E, Yeh HC, Maruthur NM. Metformin use in prediabetes among U.S. adults, 2005-2012. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:887–93. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu J, Ward E, Threatt T, Lu ZK. Metformin prescribing in low-income and insured patients with prediabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2017;57:483–7. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanks SH, Treadwell H, Bazzell A, et al. Community engaged lifestyle modification research: Engaging diabetic and prediabetic African American women in community-based interventions. J Obes. 2016; 3609289, 8 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. 2017 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/about_ahcd.htm. Accessed 17 Sept 2018.

- 17.Wu J, Davis-Ajami ML, Noxon V, Lu ZK. Venue of receiving diabetes self-management education and training and its impact on oral diabetic medication adherence. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawshani A, Rawshani A, Franzén S, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular disease in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1407–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothberg AE, McEwen LN, Kraftson AT, Fowler CE, Herman WH. Very-low-energy diet for type 2 diabetes: An underutilized therapy? J Diabetes Complicat. 2014;28:506–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association 7. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S65–72. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes Association 9. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S86–104. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association 4. Lifestyle management: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S38–50. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stellefson M, Dipnarine K, Stopka C. The chronic care model and diabetes management in US primary care settings: A systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E26. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Diabetes Surveillance System. Diagnosed Diabetes: Age-adjusted percentage, Adults with diabetes—total, 2015. Available at: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/diabetes/DiabetesAtlas.html. Accessed 17 Sept 2018.

- 25.Gopalan A, Lorincz IS, Wirtalla C, Marcus SC, Long JA. Awareness of prediabetes and engagement in diabetes risk–reducing behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:512–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portero McLellan KC, Wyne K, Villagomez ET, Hsueh WA. Therapeutic interventions to reduce the risk of progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:173–88. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S39564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes prevention program: Research-based prevention program. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/prediabetes-type2/preventing.html. Accessed 17 Sept 2018.

- 28.Espeland MA, Glick HA, Bertoni A, et al. Impact of an intensive lifestyle intervention on use and cost of medical services among overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: The action for health in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2548–56. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redmon JB, Bertoni AG, Connelly S, et al. Effect of the look AHEAD study intervention on medication use and related cost to treat cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1153–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Look AHEAD Research Group Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)