Abstract

The present study was undertaken on epidemiology and diagnosis of babesiosis in sheep and goats in Bengaluru Urban and Rural districts of Karnataka state from November 2017 to May 2018. Out of 343 (225 sheep and 118 goats) blood smears examined by Giemsa and acridine orange (AO) fluorescent dye staining methods, 3.55 and 4.0 per cent of sheep and 0.84 and 1.69 per cent of goat samples were found positive for Babesia organisms, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity was found to be higher in AO fluorescent dye staining method. In agewise susceptibility, the percent positivity was found to be higher in animals > 6 months old. In genderwise susceptibility, the percent positivity was found to be higher in females than males. Hence, AO fluorescent dye staining method is found to be very rapid and cost effective diagnostic method for treatment and control of babesiosis.

Keywords: Babesia, Diagnosis, Goats, Morphometrics, Sheep

Introduction

Among tick borne haemoprotozoan diseases, babesiosis is an economically important disease of small ruminants in tropical and subtropical countries. In India, the estimated loss due to tick borne diseases is around US$ 498.7 million per annum (Minjauw and McLeod 2003) and in the world it is roughly US$ 7000 million (FAO 1984). Among Babesia spp., Babesia motasi and Babesia ovis are considered to be pathogenic; Babesia crassa, Babesia foliata and Babesia taylori are mild to non-pathogenic in sheep and goats (Levine 1985; Kaufmann 1996).

Based on morphology, many authors have described pleomorphic forms of Babesia spp. throughout the world. Lestoquard (1925) reported a parasite (2.5 − 4.0 × 1.2 μm) in goat blood from Algeria. Thomson and Hall (1933) described B. motasi (2.5 − 3.5 × 1.2 − 1.5 μm) from sheep in northern Nigeria. Ried et al. (1976) described the parasite as a small Babesia (2 μm in length). Christensson and Thunegard (1981) reported B. motasi (3.1 × 1.9 μm) as large and small forms (2.2 × 1.8 μm). Bai et al. (2002) reported two Babesia spp. viz., B. ovis and large polymorphic form of Babesia (1.8 − 2.5 × 0.9 − 1.8 μm) from sheep in eastern part of Gansu province, China. Shayan et al. (2008) reported large polymorphic form of B. ovis (2.7 × 0.4 μm). In India, the first observation on ovine babesiosis was recorded in Mysore (Achar and Sreekantaiah 1934) and designated as B. motasi. Subsequently, the disease has been reported by Sarwar (1935), Ray and Raghavachari (1941), Madhav (1966), Jagannath et al. (1974), Prabhakar (1976), Muraleedharan et al. (1994), Vidya et al. (2011), Muthuramalingam et al. (2014) and Haq et al. (2017).

Though Giemsa staining continues to be the “gold standard method” for diagnosis of babesiosis in most of the countries with the sensitivity ranging from 10−5 to 10−6. However, considerable progress has been made with application of fluorescent dyes in diagnosis of blood parasites particularly with acridine orange (AO). The advantage of AO is that results are readily available within 3 to 10 min and has shown higher sensitivity compared to Giemsa staining in the detection of Babesia species (Bose et al. 1995). Hence, the present literature describes an application of Giemsa and AO fluorescent dye staining methods in epidemiological studies and quick detection of babesiosis.

Materials and methods

Study area and collection of samples

A total of 343 (225 sheep, 118 goats) blood samples were collected aseptically from both clinically suspected (10 sheep, 8 goats) and apparently healthy animals (215 sheep, 110 goats) without any symptoms but infested with ticks in and around Bengaluru Urban and Rural districts of Karnataka during the study period from November 2017 to May 2018 (Table 1). Out of 343 blood samples, 18 were collected from Veterinary Hospital, Veterinary College, Hebbal, Bengaluru from sheep and goats which were showing clinical signs viz., pyrexia (104–107°F), reduced appetite, watery discharge from oral and nasal cavity, respiratory distress, haemoglobinuria and pale mucous membrane. The details on age and gender were also recorded.

Table 1.

Number of blood samples found positive for babesiosis in sheep and goats by Giemsa and AO fluorescent dye staining method

| Sl. no. | Districts | Taluks | No. of samples collected | No. positive (Giemsa staining method) | No. positive (AO staining method) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep | Goats | Sheep | Goats | Sheep | Goats | |||

| 1 | Bengaluru Urban | Bengaluru North | 39 | 30 | 2 (5.12%) | 0 | 2 (5.55%) | 0 |

| Bengaluru South | 20 | 12 | 1 (5.0%) | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 0 | ||

| Bengaluru East | 28 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Anekal | 22 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | Bengaluru Rural | Devanahalli | 14 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hosakote | 28 | 12 | 1 (3.57%) | 1 (8.33%) | 2 (7.14%) | 2 (16.66%) | ||

| Doddaballapura | 38 | 17 | 1 (2.63%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Nelamangala | 36 | 13 | 3 (7.69%) | 0 | 3 (7.69%) | 0 | ||

| Total | 225 | 118 | 8 (3.55%) | 1 (0.84%) | 9 (4.0%) | 2 (1.69%) | ||

The statistical differences between the groups and methods was found to be non-significant (P<0.05)

Microscopic examination of blood smears

Two set of blood smears were made immediately after the blood collection. One set of blood smears stained with Giemsa stain were examined under a light microscope for the presence of the intra-erythrocytic piroplasms (Soulsby 1982). Second set of blood smears were stained with 0.01% AO fluorescent stain. The AO (0.01%) stain was prepared by adding 20 mg of AO powder (Himedia Laboratories) to 190 ml acetate buffer (pH 5.6). The blood smears were stained with AO stain as per the method described by Ravindran et al. (2007) with slight modification and were screened for the presence of Babesia organisms under 400 × magnification of Inverted fluorescent microscope at 460 nm (ZEISS, Germany). The morphological characterization was carried out by micrometric studies.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of data was carried out by Chi square test using graphpad prism software, version 5.01.

Results and discussion

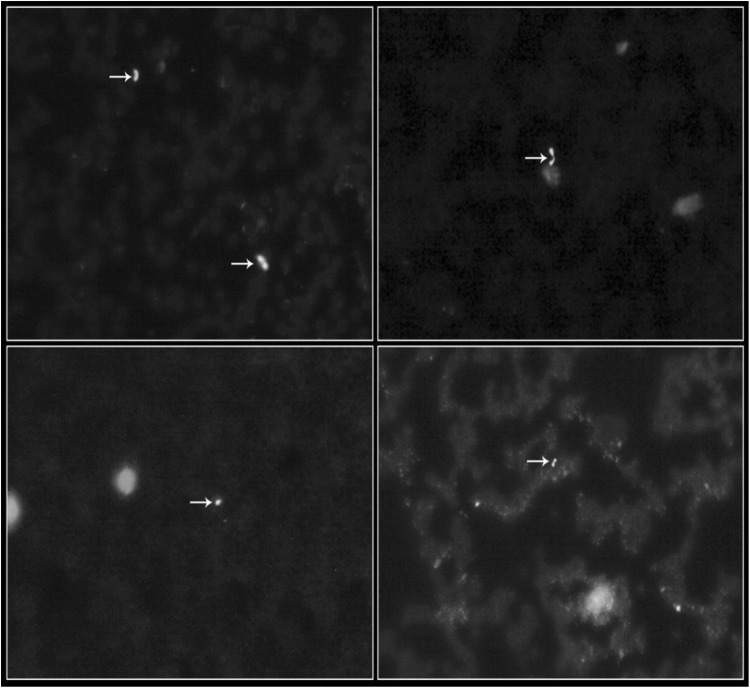

Many alternative molecular approaches to Giemsa staining have been developed but none of these methods have been able to replace Giemsa staining due to their high costs in the diagnosis of babesiosis. Several other methods have been described with use of fluorescent dye but the most extensively studied dye is AO. In the present study, out of 343 (225 sheep and 118 goats) blood samples examined by Giemsa and AO fluorescent dye staining methods, 3.55 and 4.0 per cent of sheep and 0.84 and 1.69 per cent of goats were found positive for Babesia organisms, respectively. In AO, the nucleus of the Babesia organisms fluoresced apple green color, whereas light orange colored fluorescence was observed from the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). Among eight taluks, Nelamangala revealed 7.69 per cent of positive cases (Table 1). The sensitivity of Giemsa and AO fluorescent dye staining methods was found to be 56.25 and 68.75 per cent, respectively. The specificity was found to be 99.70 and 100.0 per cent, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Acridine orange stained blood smears showing Babesia organisms (400 ×)

These findings are in accordance with Razmi et al. (2003) from Iran who recorded 23.5 (92/391) and 0.5 (2/385) per cent of B. ovis in sheep and goats, respectively. In contrast to the present findings, Naderi et al. (2017) from Iran reported higher percentage of babesiosis in goats (17.0%) than compared to sheep (12.41%). In the present study, fluorescent dye staining method showed a better visual contrast for detection of Babesia organisms due to differential fluorescence of organisms with less chance of missing the protozoan organisms and fewer artifacts, which helped in detecting subclinical cases of Babesia infection which could not be detected in Giemsa stained blood smear indicating higher sensitivity of fluorescent dye staining when compared to Giemsa staining technique. Similar observations were also reported by Hansen et al. (1970); Bose et al. (1995); Ravindran et al. (2007) and Nair et al. (2011).

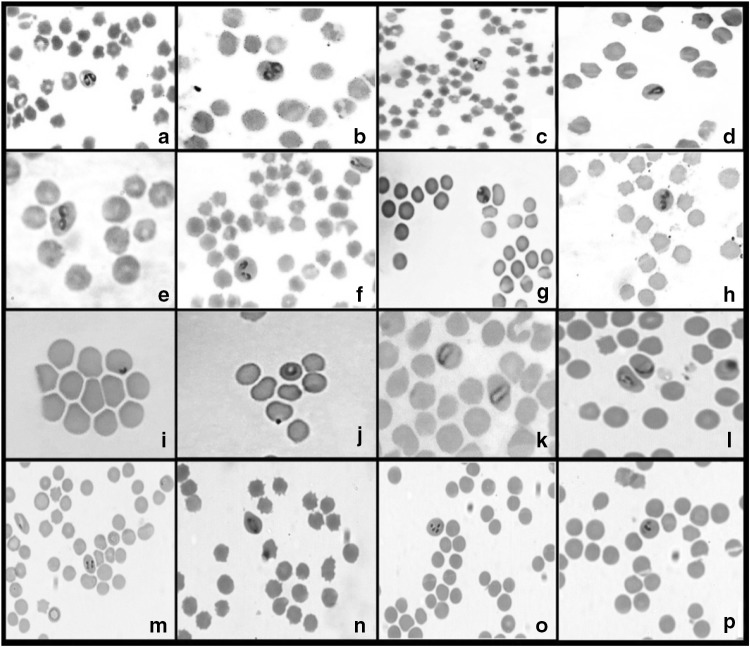

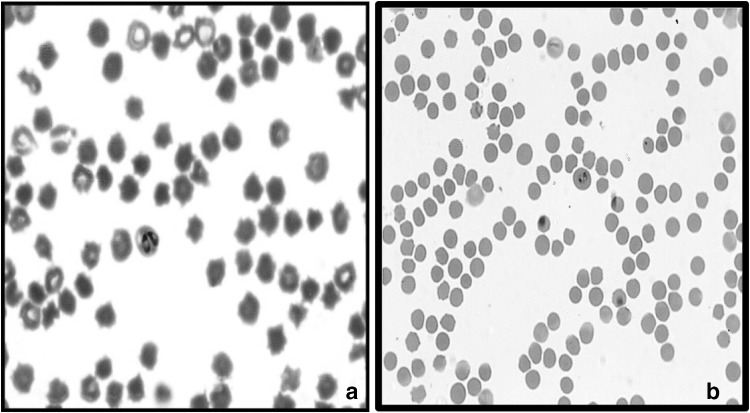

Examination of Giemsa stained blood smears by microscopy revealed the presence of highly pleomorphic organisms with predominant of single (31%) and paired pyriforms (28%) followed by amoeboid (17%), oval (11%), elongated (4%), ring (4%) and other forms (5%) (Fig. 2). The micrometric studies revealed two forms of B. ovis organisms in both sheep and goats which was later confirmed by PCR (Figs. 3 & 4). Small form of Babesia was observed in three sheep samples and measured about 1.0 to 1.31 μm in length and 0.5 to 2.5 μm in breadth. A large form of Babesia organism was observed in three sheep and two goat samples with 1.8 to 2.7 μm in length and 0.9 to 1.5 μm in breadth. This is the first report from India on occurrence of two forms of organisms in B. ovis. The parasitaemia percentage ranged from 1.0 to 1.8 in clinically and microscopically confirmed cases.

Fig. 2.

Pleomorphic forms of Babesia organisms in Giemsa stained blood smears (1000 ×). a–c Paired pyriforms with acute angle, d single pyriform, e–h paired forms with obtuse angle, i ring form, j Amoeboid form, k elongated form, l–p Other forms

Fig. 3.

Large (a) and small form of Babesia (b) organisms (1000 ×)

Fig. 4.

PCR gel showing amplification of 186 bp DNA fragment specific for B. ovis. Lane 1: 100 bp DNA Ladder, Lane 3: Negative control, Lane 4: No template control, Lane 2, 5, 6: Field samples of sheep, Lane 7, 8: Field samples of goats

Different morphological forms of piroplasms observed in the present study were in agreement with Shayan et al. (2008) from Iran; Zangana and Naqid (2011) from Iraq and Sevinc et al. (2013) from Turkey and Spain who have observed different morphological forms of piroplasms viz., single and paired pyriforms, amoeboid forms, oval forms, elongated forms, ring forms, three leaf shaped single sub-spherical and other forms. Similar to the level of parasitaemia recorded during this study, Altay et al. (2008) reported 0.01 to one per cent of parasitemia in sheep from Turkey, Papadopoulos et al. (1996) recorded one per cent of parasitemia in Babesia infected sheep and goats from Macedonia region of Greece. However, Yeruham et al. (1996) from Israel recorded higher parasitemia of 5.3 and 7.04 per cent in ewes and hoggets, respectively. These variations in the percentage of parasitemia could be attributed to the stage of the disease at which the blood smears were made from the animals because, high parasitemia will be observed during acute/clinical stage of the disease whereas, low parasitemia is a characteristic feature of carrier or chronic stage of the disease (Yin et al. 2007). Fall in blood haemoglobin values of infected animals was the significant haematological change recorded during this study and is in accordance with Haq et al. (2017) from Jammu and Kashmir (India); Zangana and Naqid (2011) from Iraq and Vidya et al. (2011) from Karnataka (India).

Agewise susceptibility revealed that in below six months of age group, out of 68 sheep and 30 goats examined, 4.41 and zero per cent were found to be positive for Babesia spp. respectively. In above 6 months of age, out of 157 sheep and 88 goats, 5.73 and 4.54 per cent were found to be positive for Babesia spp. respectively. However, the lower infection was observed in young animals less than 6 months of age.

In genderwise susceptibility, out of 95 blood smears examined from males, 4.10 and zero per cent of sheep and goats were found positive for babesiosis, respectively. In 248 females, 5.92 per cent of sheep and 4.16 per cent of goats were found positive for babesiosis. The present study showed that infection is higher in females than males. During this study, there was no statistically significant differences between gender (males and females) and age groups in both sheep and goats (P < 0.05) which correlates with the findings of Reijbei et al. (2014) from Tunisia; Ali shah et al. (2017) from Pakistan; Aktaş et al. (2007) from Bazmani et al. (2018) from Iran.

Conclusion

In conclusion, babesiosis in sheep and goats caused by B. ovis can be considered as an emerging disease in Karnataka state. AO fluorescent dye staining method was found to be very sensitive, specific and cost effective diagnostic parasitological technique for epidemiological studies and quick detection of disease. However, it needs further research work on prevalence of B. ovis and ticks in other regions of Karnataka with their probable role in transmission of the disease.

Acknowledgements

The facilities provided to carry out research work through Centre of Advanced Faculty Training, ICAR, New Delhi is greatfully acknowledged.

Authors’ contribution

SK, GSM and PED conceived of or designed study. SK performed research. SK, JNL and SS analyzed data. SK and GSM contributed new methods or models. SK and GSM wrote the paper.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The work was carried out in a Teaching Veterinary Clinical Hospital and Research Institute, Veterinary College, Bengaluru, Karnataka Veterinary, Animal and Fisheries Sciences University (KVAFSU), Bidar, India. The KVAFSU 2004 Act legislates collection of clinical materials for the diagnosis and treatment of animals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Achar SD, Sreekantaiah GN. A note on Babesia motasi Wenyon (1926) in sheep in Mysore state Indian. Vet J. 1934;10:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas M, Altay K, Dumanli N. Determination of prevalence and risk factors for infection with Babesia ovis in small ruminants from Turkey by polymerase chain reaction. Parasitol Res. 2007;100:797–802. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Shah SS, Khan MI, Rahman HU. Epidemiological and hematological investigations of tick-borne diseases in small ruminants in Peshawar and Khyber Agency, Pakistan. J Adv Parasitol. 2017;4(1):15. [Google Scholar]

- Altay K, Aktas M, Dumanli N. Detection of Babesia ovis by PCR in Rhipicephalus bursa collected from naturally infested sheep and goats. Res Vet Sci. 2008;85:116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q, Liu G, Liu D, Ren J, Li X. Isolation and preliminary characterization of a large Babesia spp. from sheep and goats in the eastern part of Gansu Province, China. Parasitol Res. 2002;88:S16–S21. doi: 10.1007/s00436-001-0563-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazmani A, Abolhooshyar A, Imani-Baran A, Akbari H. Semi-nested polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Babesia spp. in small ruminants from Northwest of Iran. Vet World. 2018;11(3):268–273. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.268-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose R, Jorgensen WK, Dalgliesh RJ, Friedhoff KT, De Vos AJ. Current state and future trends in the diagnosis of babesiosis. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:61–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensson D, Thunegard E. Babesia motasi in sheep on the island of Gotland in Sweden. Vet Parasitol. 1981;9:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(81)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) (1984) Ticks and tick-borne disease control. A practical field manual, vol 1, Tick Control. FAO, Rome, pp 299

- Hansen WD, Hunter DT, Richards DE, Allred L. Acridine orange in the staining of blood parasites. Parasitol. 1970;56:386–387. doi: 10.2307/3277684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq AU, Tufani N, Gugjoo MB, Nabi SU, Malik HU. Therapeutic amelioration of severely anaemic local Kashmiri goats affected with babesiosis. Adv Anim Vet Sci. 2017;5(11):463–467. doi: 10.17582/journal.aavs/2017/5.11.463.467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannath MS, Hedge KS, Shivaram K, Nagaraja KV. An outbreak of babesiosis in sheep and goats and its control. Mysore J Agri Sci. 1974;8:441–443. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann J (1996) Text book of parasitic infections of domestic animals. Birkhauser Verlag, Postfach 133, CH-4010 Basel, Schweiz. pp 169–170

- Lestoquard F (1925) Troisieme note sur les piroplamoses du mouton en Algerie La piroplasmosevraie: Piroplasma (s.sstr.) ovis (n. sp.). Comparison Babesiella ovis. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 18:140

- Levine ND (1985) Veterinary protozoology. 1st edition. Iowa State University Press, Ames pp 306–309

- Madhav AKR. Some observations on Babesia motasi infection in sheep in Andhra Pradesh. Indian Vet J. 1966;43:785–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minjauw B, Mcleod A (2003) Tick-borne diseases and poverty. The impact of ticks and tick-borne diseases on the livelihood of small scale and marginal livestock owners in India and eastern and southern Africa. Research report, DFID Animal Health Programme, Centre for Tropical Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK

- Muraleedharan K, Ziauddin KS, Margoob HP, Puttabytappa B, Seshadri SJ. Prevalence of parasitic infection among small domestic animals. Karnataka J Agric Sci. 1994;7:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Muthuramalingam T, Pothiappan P, Gnanaraj P, Tensingh Meenakshisundaram S, Pugazhenthi TR, Parthiban S. Report on an outbreak of babesiosis in Tellicherry Goats. Indian J Vet Anim Sci Res. 2014;43:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi A, Nayebzadeh H, Gholami S. Detection of Babesia infection among human, goats and sheep using microscopic and molecular methods in the city of Kuhdasht in Lorestan Province, West of Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2017;41(3):837–842. doi: 10.1007/s12639-017-0899-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair AS, Ravindran R, Lakshmanan B, Kumar SS, Tresamol PV, Saseendranath MR, Senthilvel K, Rao JR, Tewari AK, Ghosh S. Haemoprotozoa of cattle in Northern Kerala, India. Trop Biomed. 2011;28(1):68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos B, Brossard M, Perie NM. Piroplasms of domestic animals in the Macedonia region of Greece. Piroplasms of small ruminants. Vet Parasitol. 1996;63(1–2):67–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar KS (1976) Studies on theileriosis of sheep with special reference to its prevalence in Karnataka and haematology in splenectomized carriers. M. V. Sc. Thesis, University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore

- Ravindran R, Lakshmanan B, Sreekumar C, John L, Gomathinayagam S, Mishra AK, Tewari AK, Rao JR. Acridine orange staining for quick detection of blood parasites. J Vet Parasitol. 2007;21:85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ray HN, Raghavachari K. Observations on Babesia foliata sp. from a sheep. Indian J Vet Sci. 1941;11:239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Razmi GR, Naghibi A, Aslani MR, Dastjerdi K, Hossieni H. An epidemiological study on Babesia infection in small ruminants in Mashhad suburb, Khorasan Province, Iran. Small Rum Res. 2003;50:39–44. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4488(03)00107-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reijbei MR, Gharbi M, Mhadhbi M, Mabrouk W, Ayar B, Nasfi I, Jedidi M, Sassi L, Rekik M, Darghouth MA. Prevalence of piroplasms in small ruminants in North-West Tunisia and the first genetic characterisation of Babesia ovis in Africa. Parasite. 2014;21:23–31. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried JF, Armour J, Jennings FW, Urquhart GM. Babesia in sheep: first-isolation. Vet Rec. 1976;99:419. doi: 10.1136/vr.99.21.419-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar SM. A hitherto undescribed piroplasm of goats (Piroplasma taylori) Indian J Vet Sci Anim Husb. 1935;5:71–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sevinc F, Sevinc M, Ekici OD, Yildiz R, Isik N, Aydogdu U. Babesia ovis infections: detailed clinical and laboratory observations in the pre and post treatment periods of 97 field cases. Vet Parasitol. 2013;191:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayan P, Hooshmand E, Nabian S, Rahbari S. Biometrical and genetical characterization of large Babesia ovis in Iran. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:217–221. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0960-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 7. New Delhi: Elsevier; 1982. p. 763. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JG, Hall GN. The occurrence of Babesia motasi Wenyon, 1926, in sheep in northern Nigeria, with a discussion on the classification of the piroplasms. J Comp Pathol Ther. 1933;46:218–231. doi: 10.1016/S0368-1742(33)80028-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vidya MK, Puttalakshamma GC, Halbmandge SC, Kasaralikar VK, Bhoyar R, Patil NA (2011) Babesia ovis infection in goat—a case report. 29th convention and veterinary symposium, ISVM, Feb. 17–19th 2011, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Mumbai Veterinary College, MAFSU, Mumbai, 400 012, pp 35

- Yeruham I, Hadani A, Galker F, Rosen S. The seasonal occurrence of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on sheep and in the field in the Judean area of Israel. Exp Appl Acarol. 1996;20:47–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00051476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Leonhard S, Luo J, Seitzer U, Ahmed JS. Ovine theilerioisis in China: a new look at an old story. Parasitol Res. 2007;101(2):191–195. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangana IK, Naqid IA. Prevalence of piroplasmosis (Theileriosis and Babesiosis) among goats in Duhok Governorate. J Vet Sci. 2011;4(2):50–57. [Google Scholar]