Abstract

The deadliest form of human malaria is primarily caused by the protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum. These parasites establish pathogenicity in the human host with a very low number of sexual forms or gametocytes, which are transmitted to the mosquitoes. Several studies have reported that exposing artemisinin-sensitive P. falciparum rings to a low concentration of dihydroartemisinin (DHA) results in dormancy, and the artemisinin-induced dormant (AID) forms are recovered into normal growth stages after 5–20 days. In this study, artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum parasites were tested for the development of AID forms and their recovery. Interestingly, it was found that exposure of an asynchronous culture of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum IPC 5202 to DHA, a line carrying a mutation in the PfK13 gene that is linked to artemisinin resistance, also results in dormancy. Both the ring and some late stages of these AID forms recovered after 10–15 days. Furthermore, a high proportion of the recovered dormant forms developed into sexual forms or gametocytes after 3–4 weeks, which is almost a 7–8 times higher rate of conversion of asexual to sexual forms (gametocytes) or the malaria transmissible forms. In contrast, only early ring forms of artemisinin-sensitive parasites recovered slowly, and additional exposure of these parasites to artemisinin resulted in complete clearance within a week. This is in contrast to the resistant parasites exposed to a second dose of artemisinin, which resulted in a very high rate of dormancy and recovery into sexual forms or gametocytes.

Keywords: Protozoan, Plasmodium falciparum, Dihydroartemisinin, Resistance, Gametocytes

Introduction

Among the five species of Plasmodium parasites that cause human malaria, Plasmodium falciparum is the deadliest (Organization WHO 2016). Malaria parasite goes through both asexual and sexual developmental stages to complete its life cycle. The asexual development occurs in human or in other primate hosts, while the sexual development occurs in a mosquito vector. During the asexual development of P. falciparum in the human host, a very small proportion of asexual schizonts are committed to the development of sexual forms or gametocytes (Talman et al. 2004; Bruce et al. 1990; Eksi et al. 2012; Josling and Linas 2015; Smith et al. 2000; Silvestrini et al. 2000). These gametocytes are the transmissible forms of malaria parasites to mosquito vectors from vertebrate hosts (Drakeley et al. 2006; Eksi et al. 2012). Currently, there is no malaria vaccine available, but anti-malarial drugs have been used to treat and control malaria transmission for the last several decades (Organization WHO 2016). Antimalarial drug use has resulted in the development of P. falciparum parasites resistant to quinolones, folates and recently, artemisinin derivatives (Bousema et al. 2006; Mockenhaupt et al. 2005a, b; Oesterholt et al. 2009; Organization WHO 2016; Abdul-Ghani et al. 2015; Straimer et al. 2015). In addition to conferring resistance to antimalarial drugs, the resistant parasites have enhanced transmissibility to mosquito vectors (Abdulla et al. 2016; Dondrop et al. 2009; Mockenhaupt et al. 2005a, b; La Bras and Durand 2003; Mendez et al. 2002; Makanga 2014; Mockenhaupt et al. 2005a, b; Abdul-Ghani et al. 2014). The increased transmissibility is associated with antimalarial drug-induced stress on the parasite, which favors increased gametocyte production, which in turn results in increased transmission of drug-resistant malaria (Abdulla et al. 2016; Peatey et al. 2009). The antimalarial drug artemisinin was initially very effective in treating malaria. However, the continued use of oral artemisinin-based monotherapies contributed to the development of resistance to artemisinin and its derivatives (Cheng et al. 2012; Dondrop et al. 2009; Mockenhaupt et al. 2005a, b; Organization WHO 2016; Teuscher et al. 2010, 2012). Later, artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) was introduced in which artemisinin was the principle component (Organization WHO 2016). ACT offered higher clinical efficacy against P. falciparum, reduced the pace at which resistance developed, and lowered gametocyte prevalence and density (Adjuik et al. 2004). Very recently, artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum lines have been identified in malaria-endemic regions, and mutations in the P. falciparum k13 gene encoding a Kelch-propeller (K13-propeller) domain-containing protein have been correlated with artemisinin resistance (Ariey et al. 2014; Straimer et al. 2015; Witkowski et al. 2013).

Importantly, among the antimalarial drugs used to date, only artemisinin and primaquine have gametocytocidal properties and activity against most asexual stages of P. falciparum. Artemisinin has a very short life, which is why the treatment failures were common when used as monotherapy. A partner drug was needed to clear the remaining parasites once artemisinin is out of the system. Also because artemisinin need free heme/iron for activation, mature stages which digests large amounts of hemoglobin are more susceptible to artemisinin as compared to early ring stages. Because artemisinin has short half-life and early rings are a bit refractory to it, by extending ring stages parasites can survive and recrudesce, resulting in treatment failure. Nevertheless, very early ring forms (0–3 h old rings) can survive after 6 h of exposure with a clinically-relevant concentration (700 nM) of artemisinin, and the measurement of the percentage of rings that survive after the treatment has become a standard assay system (known as the Ring-stage Survival Assay or RSA) for the determination of artemisinin resistance in vitro (Ariey et al. 2014; Witkowski et al. 2013; Xie et al. 2016). Several studies have shown that these early rings are refractory to immediate clearance, and they tend to survive longer as growth-arrested dormant stages (Cheng et al. 2012; Teuscher et al. 2012; Teuscher et al. 2012; Tucker et al. 2012). These dormant parasites recrudesce days after treatment with artemisinin (Cheng et al. 2012). In clinical settings, the elimination of these stages may be achieved by ACTs with other known malarial drugs but there is no clear evidence to support this conclusion.

However, artemisinin-induced dormancy, and its relevance to the development of resistance and transmissibility is not clearly understood. In particular, artemisinin-induced development of dormant forms among resistant parasites has not been studied. In this report, studies were conducted on the development of artemisinin-induced dormancy (AID) by using an artemisinin-resistant (tolerant and not cleared) P. falciparum parasite with a mutated Pfk13 gene identified by Straimer et al. 2015. The recovery of AID forms and their transformation into asexual and sexual forms (gametocytes) were analyzed, and it was found that a very high percentage of AID forms resulted in gametocytes. The outcome of this study provides information to help understand the role of Pfk13 gene mutations in the development of dormancy among the artemisinin-tolerant parasites and their further development into gametocytes.

Materials and methods

Materials

The O+ human erythrocytes used for the P. falciparum in vitro culture were obtained from the Interstate Blood Bank (Interstate Blood Bank, Inc. Memphis, TN Center). Erythrocytes were separated from leukocytes by using a Sepacel filter (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Memphis, TN). A+ human serum was also obtained from the Interstate Blood Bank, pooled and heat-inactivated as described previously (Cohn et al. 2003). RPMI, glutamine, hypoxanthine and the antibiotic gentamicin were obtained from Invitrogen (Invitrogen®). Glycerolyte 57 (57% glycerol, 16 g/L of sodium lactate, 300 mg/L of KCl and 25 mM sodium phosphate) was purchased from Baxter/Fenwal.

Methods

Preparation of P. falciparum growth medium

Plasmodium falciparum culture medium consisted of RPMI (Invitrogen, Cat # 21870-084) supplemented with the following components: 10% pooled and heat-inactivated A+ serum, 2 mM l-Glutamine, 0.2% d-glucose, 0.2 mM Hypoxanthine pH 7.5, 25 mM Hepes buffer pH 7.5, 0.02 mg/L Gentamicin and 0.24% sodium bi-carbonate. The reconstituted medium was filtered through an 0.22 µM filter unit (Corning Cat # 530758). The complete RPMI medium was stored at 4 °C for a maximum of 2 weeks.

In vitro culture of asexual stages (rings, trophozoites and schizonts) of P. falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum strain NF54 parasites and P. falciparum IPC5202 (listed in Table 1) used in this study were obtained from BEIR (www.bei.org). Asexual stages of these parasites were cultured as described previously (Eksi et al. 2012; Cohn et al. 2003; Trager and Jensen 1976).

Table 1.

Artemisinin-resistant and -sensitive P. falciparum parasites and the altered amino acid (aa) positions in Pfk13 are provided

| Parasite ID # | Common name | Genetic change | Altered aa position | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRA-1240 | PfIPC5202 | AGA-ACA | R539T | Resistant |

| MRA-1000 | PfNF54 | Wild-type | No change | Sensitive |

In vitro culture of P. falciparum gametocytes

In vitro culture of various stages of P. falciparum gametocytes was performed as described previously (Eksi et al. 2012).

Determination of gametocytemia

Gametocytemia was monitored by daily microscopic examination of methanol-fixed blood smears from in vitro cultures. Smears were stained with 5.0% Giemsa for 40 min, rinsed, and dried prior to viewing. Approximately 1000 red blood cells (RBCs) per experimental slide were counted and gametocytes, as well as stages present on examination, were recorded.

Establishment of artemisinin induced dormant (AID) forms of P. falciparum

In order to establish P. falciparum AID forms in vitro, the artemisinin-resistant line P. falciparum IPC 5202 was cultured to 10% asexual stages containing rings, trophozoites and schizonts, and this mixed culture was treated with various concentrations of DHA. DHA-treated cultures were recovered by centrifugation, washed and the parasites were exposed a second time with various concentrations of DHA. At this point almost all of the parasites reached pyknotic forms known as Artemisinin Induced Dormant forms (AID forms). The development of gametocytes was monitored by maintaining the culture for extended periods of time with daily media change without the addition of any new erythrocytes. Gametocytemia was calculated by manual counting of both asexual stages and gametocytes in Giemsa-stained thin blood smears.

Results

Almost all antimalarial drugs currently used to control P. falciparum malaria parasite growth and development target the asexual-stages, and all available data suggest that most of these drugs have no effect on gametocytes. The goal of the elimination of malaria will be achieved only by the development of antimalarial drugs that not only kill the asexual parasite but also block transmission by either reducing gametocytogenesis or gametogenesis. Peatey et al. (2009) tested 8 different commonly used anti-malarials against asexual stages of P. falciparum and found an increased gametocytogenesis in all antimalarial drug-treated cultures.

Antimalarial drug-resistant P. falciparum mutant parasites possess a transmission advantage compared to susceptible parasites

A few other studies also found that the increased gametocytogenesis results in the transmission of antifolate- and chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum. For example, resistance mutations in the Pfdhps, Pfdhfr and Pfcrt genes result in a malaria transmission advantage compared to wild-type parasites under drug pressure (Mayke et al. 2009). Also, in addition to a transmission advantage of Pfcrt mutant parasites in the human host, a higher gametocyte prevalence or density has also been observed (Mendez et al. 2002; Hallett et al. 2004). Studies using Atovaquone-resistant parasite lines also showed an increased gametocytogenesis in the presence of atovoquine and transmission [MS thesis (Aylor (2010)]. In the current study, AID form development and the gametocytogenesis profile of an artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum IPC 5202 parasite are reported.

Development of AID forms in artemisinin-sensitive P. falciparum parasites

In contrast to most other anti-malarial drug resistance mechanism, artemisinin resistance is defined as delayed parasite clearance following treatment with an artesunate monotherapy or with an artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). Unlike other antimalarials, in artemisinin-sensitive parasites such as NF54 treated with 700 nM artemisinin for 6 h, AID forms result but the treatment of these AID forms with another dose of DHA results in complete clearance of these forms within a few days, and further development of sexual forms or gametocytes is not observed in those artemisinin-sensitive parasites. The development of AID forms in several artemisinin-sensitive P. vinckei parasites have also been observed previously (LaCrue et al. 2011). The development of AID forms in artemisinin-resistant parasites have not been tested previously.

Development of AID forms in artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum and upregulation of gametocytogenesis

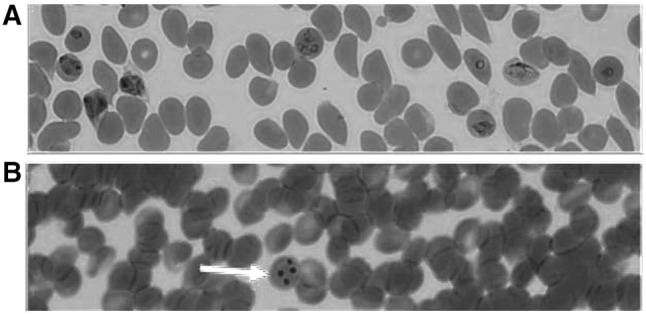

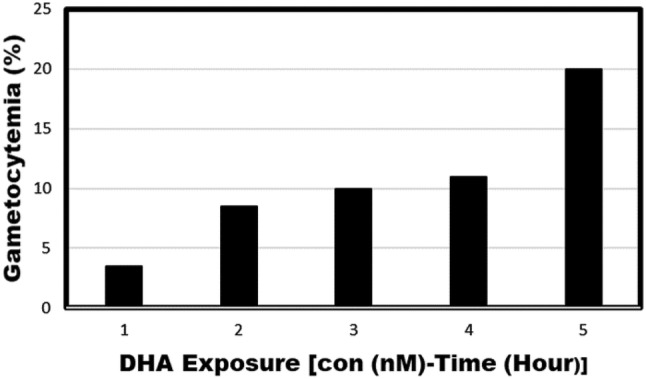

In this study, the development of AID forms was tested in an artemisinin-resistant parasite identified in previous studies by Straimer et al. 2015. The P. falciparum parasites used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. falciparum IPC 5202 and P. falciparum NF54 were exposed to 700 nM of DHA for 6 h in an in vitro P. falciparum culture system (P-700; primary concentration of DHA), after 6 h the drug was removed by centrifugation and washing with RPMI. AID forms were analyzed by Giemsa-stained blood smears (Fig. 1, Panel B). These drug-exposed cultures were maintained for 5–7 days in drug-free growth medium in the in vitro culture conditions. On day 5–7, it was observed that the artemisinin-exposed P. falciparum IPC 5202 parasites showed a slow recovery from dormancy (data not shown). At this time point, the culture was divided into four equal portions, and parasites were collected by centrifugation. One portion was treated with a second dose of 700 nM (S-700; Secondary concentration of DHA) of DHA for 6 h (P-700-S-700-6h), a second portion was treated with a second dose of 700 nM of DHA for 24 h (P-700-S-700-24h), a third portion was treated with 100 nM of DHA for 70 h (P-700-S-100-70h), and a fourth portion was maintained without any secondary treatment of DHA (P-700). These cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 15–35 days with daily media changes. The gametocyte development was monitored every other day by blood smearing and final gametocytemia was calculated when they reached stage IV or V. As a control, a standard gametocyte culture was maintained for P. falciparum IPC 5202 without any added DHA (No DHA). As shown in Fig. 2, the development of sexual forms varied with the duration and concentration of DHA. In particular, longer exposure with a low concentration of DHA resulted in an effective conversion of AID forms into gametocytes in P. falciparum IPC 5202 and gametocytes were not observed in P. falciparum NF54 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Artemisinin-Induced Dormant (AID) forms of an artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum line. P. falciparum parasite PfIPC5202 was cultured in vitro in the absence of (a) or exposure to DHA (b) for 6 h, washed and allowed to grow for another 16 h in the absence of DHA. Giemsa-stained blood smears were prepared and photographed using a phase contrast microscope. a shows various asexual stages such as rings, trophozoites and schizonts, b depicts the AID forms marked by a red arrow (color figure online)

Fig. 2.

Upregulation of gametocytogenesis in AID forms: P. falciparum IPC 5202 was exposed to 700 nM of DHA for 16 h and the culture was maintained for 5 days. On day 5, the culture was divided into four equal portions. One portion, Bar #3 (P700-S700-6h), was treated with a second dose of 700 nM of DHA for 6 h, a second portion, Bar #4 (P700-S700-24h), was treated with a second dose of 700 nM of DHA for 24 h, a third portion, Bar #5 (P700-S100-70h) was treated with 100 nM of DHA for 70 h, and a fourth portion, Bar #2 (P700S0) was maintained without any further treatment of a second dose of DHA.. These cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 20-40 days with daily media changes. The gametocyte development was monitored every other day and final gametocytemia was calculated when they reached stage IV or V. As a control, a standard gametocyte culture was maintained for P. falciparum IPC 5202 without any added DHA, Bar #1 (no DHA). P-first dose of DHA; S-second dose of DHA

Conclusions and discussion

These results suggest that artemisinin-resistant parasites exposed to 700 nM concentration of DHA, which is equivalent to ~ 100 times more than the IC50 (7–8 nM) of artemisinin, resulted in the formation of AID forms. A second exposure of these AID forms with either the same or lower concentrations of artemisinin resulted in the AID forms acquiring a very high rate of conversion to sexual forms or gametocytes. In particular, longer exposure of the parasites with a lower concentration of DHA led to a very high rate of conversion of AID forms into gametocytes. It is alarming to note that treatment of P. falciparum-infected patients with infrequent and lower doses of DHA may result in the upregulation of gametocyte production and the eventual transmission of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum malaria. This also indicates that caution should be exercised in administrating an effective dose of artemisinin for a complete removal of parasites from the blood stream. Further studies using additional artemisinin-resistant parasites are required to identify specific domains in the Pfk13 protein that are involved in the formation of AID forms and gametocyte development in P. falciparum, and their further transmission of malaria.

Acknowledgements

The following reagents were obtained through the BEI Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH: Plasmodium falciparum, Strain Pf NF54 and Pf IPC5202 were contributed by MG Dowler and Didier Ménard, respectively.

Authors contribution

TR conceived and devised the study, designed and performed all experiments for the implementation of the research, collected data and analyzed results, made interpretations, collected references, wrote the manuscript, read and submitted the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The research study was conducted as per the National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA guidelines on using blood and blood borne pathogens. This study was conducted in a Bio Safety Level (BSL2) facility approved by the institution. Animals were not used in this study. Human subjects were not involved in this study.

Consent for participation

Not applicable. Human subjects did not participate or were not involved in this study. The blood and serum samples used in this study were obtained from Interstate Blood Bank (Interstate Blood Bank, Inc. Memphis, TN Center).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdul-Ghani R, Farag HF, Allam AF, Azazy AA. Measuring resistant-genotype transmission of malaria parasites: challenges and prospects. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(4):1481. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3789-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Ghani R, Basco LK, Beier JC, Mahdy M. Inclusion of gametocyte parameters in anti-malarial drug efficacy studies: filling a neglected gap needed for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2015;14:413. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0936-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla S, WWARN Gametocyte Study Group et al. Gametocyte carriage in uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria following treatment with artemisinin combination therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMC Med. 2016;14:79. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0621-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjuik M, Babiker A, Garner P, Olliaro P, Taylor W, White N. Artesunate combinations for treatment of malaria: meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;363:9–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505(7481):30. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousema JT, Schneider P, Gouagna LC, Drakeley CJ, Tostmann A, Houben R, Githure JI, Ord R, Sutherland CJ, Omar SA, Sauerwein RW. Moderate effect of artemisinin-based combination therapy on transmission of Plasmodium falciparum. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1151–1159. doi: 10.1086/503051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MC, Alano P, Duthie S, Carter R. Commitment of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to sexual and asexual development. Parasitology. 1990;100:191–200. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000061199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q, Kyle DE, Gatton ML. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: a process linked to dormancy? Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2012;2:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn JV, Alkhalil A, Wagner MA, Rajapandi T, Desai SA. Extracellular lysines on the plasmodial surface anion channel involved in Na+ exclusion. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;132(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NP, Lindegardh N, Socheat D, White NJ. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakeley C, Sutherland C, Bousema JT, Sauerwein RW, Targett AT. The epidemiology of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes: weapons of mass dispersion. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eksi S, Morahan BJ, Haile Y, Furuya T, Jiang H, et al. Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte development 1 (Pfgdv1) and gametocytogenesis early gene identification and commitment to sexual development. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(10):1002964. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett RL, Sutherland CJ, Alexander N, Ord R, Jawara M, Drakeley CJ, Pinder M, Walraven G, Targett GAT, Alloueche A. Combination therapy counteracts the enhanced transmission of drug-resistant malaria parasites to mosquitoes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3940–3943. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3940-3943.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josling GA, Llinás M. Sexual development in Plasmodium parasites: knowing when it’s time to commit. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:573–587. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCrue AN, Scheel M, Kennedy K, Kumar N, Kyle DE. Effects of artesunate on parasite recrudescence and dormancy in the rodent malaria model Plasmodium vinckei. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bras J, Durand R. The mechanisms of resistance to antimalarial drugs in Plasmodium falciparum. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17(2):147–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makanga M. A review of the effects of artemether-lumefantrine on gametocyte carriage and disease transmission. Malar J. 2014;13:291. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez F, Munoz A, Carrasquilla G, et al. Determinants of treatment response to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and subsequent transmission potential in falciparum malaria. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:230–238. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockenhaupt FP, Ehrhardt S, Dzisi SY, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, and double-blind trial on sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine alone or combined with artesunate or amodiaquine in uncomplicated malaria. Trop Med and Int Health. 2005;10:512–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockenhaupt FP, Bousema JT, Eggelte TA, Schreiber J, St E, Wassilew N, Otchwemah RW, Sauerwein RW, Bienzle U. Plasmodium falciparum dhfr but not dhps mutations associated with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment failure and gametocyte carriage in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10(9):901–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterholt MJ, Alifrangis M, Sutherland CJ, Omar SA, Sawa P, Howitt C, Gouagna L, Bousema T. Submicroscopic gametocytes and the transmission of antifolate-resistance Plasmodium falciparum in Western Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WHO (2016) World malaria report 2016

- Peatey C, Skinner-Adams T, Dixon MWA, McCarthy J, Gardiner D, Trenholme K. Effect of antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. J Inf Dis. 2009;200:1518–1521. doi: 10.1086/644645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestrini F, Alano P, Williams JL. Commitment to the production of male and female gametocytes in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 2000;121:465–471. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099006691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TG, Lourenço P, Carter R, Walliker D, Ranford-Cartwright LC. Commitment to sexual differentiation in the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 2000;121:127–133. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099006265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straimer J, et al. Drug resistance. K13-propeller mutations confer artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Science. 2015;347:428–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1260867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman AM, Domarle O, McKenzie FE, Ariey F, Robert V. Gametocytogenesis: the puberty of Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2004;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher F, Gatton ML, Chen N, Peters J, Kyle DE, Cheng Q. Artemisinin-induced dormancy in Plasmodium falciparum: duration, recovery rates, and implications in treatment failure. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1362–1368. doi: 10.1086/656476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher F, Chen N, Kyle DE, Gatton ML, Cheng Q. Phenotypic changes in artemisinin resistant Plasmodium falciparum lines in vitro: evidence for decreased sensitivity to dormancy and growth inhibition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:428–431. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05456-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasite in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker MS, Mutka T, Sparks K, Patel J, Kyle DE. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of in vitro-selected artemisinin-resistant progeny of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):302–314. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, et al. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in vitro and ex vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie SC, Dogovski C, Hanssen E, Chiu F, Yang T, Crespo MP, Stafford C, Batinovic S, Teguh S, Charman S, Klonis N, Tilley L. Haemoglobin degradation underpins the sensitivity of early ring stage Plasmodium falciparum to artemisinins. J Cell Sci. 2016;129(2):406–416. doi: 10.1242/jcs.178830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]