Abstract

Background

Approximately 25 million people in the USA are limited English proficient (LEP). When LEP patients receive care from physicians who are truly language concordant, some evidence show that language disparities are reduced, but others demonstrate worse outcomes. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to compare the impact of language-concordant care for LEP patients with that of other interventions, including professional and ad hoc interpreters.

Methods

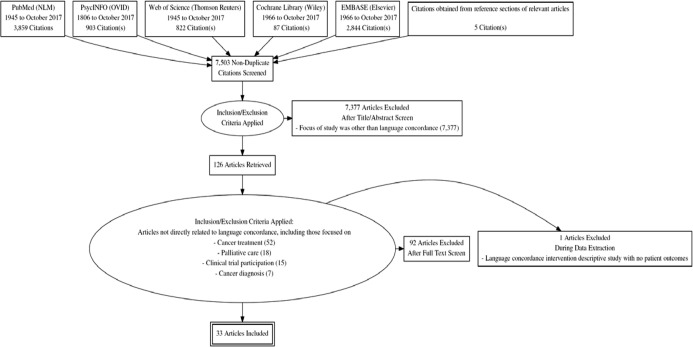

Data was collected through a systematic review of the literature using PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE in October 2017. The literature search strategy had three main components, which were immigrant/minority status, language barrier/proficiency, and healthcare provider/patient relationship. The quality of the articles was appraised using the Downs and Black checklist.

Results

The 33 studies were grouped by the outcome measure studied, including quality of care (subdivided into primary care, diabetes, pain management, cancer, and inpatient), satisfaction with care/communication, medical understanding, and mental health. Of the 33, 4 (6.9%) were randomized controlled trials and the remaining 29 (87.9%) were cross-sectional studies. Seventy-six percent (25/33) of the studies demonstrated that at least one of the outcomes assessed was better for patients receiving language-concordant care, while 15% (5/33) of studies demonstrated no difference in outcomes, and 9% (3/33) studies demonstrated worse outcomes in patients receiving language-concordant care.

Discussion

The findings of this review indicate that, in the majority of situations, language-concordant care improves outcomes. Although most studies included were of good quality, none provided a standardized assessment of provider language skills. To systematically evaluate the impact of truly language-concordant care on outcomes and draw meaningful conclusions, future studies must include an assessment of clinician language proficiency. Language-concordant care offers an important way for physicians to meet the unique needs of their LEP patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: communication barriers, physician–patient communication, quality of care, language access

INTRODUCTION

Approximately one in five people in the USA speaks a language other than English at home1 with Spanish, Chinese, French, Tagalog, and Vietnamese being the most common ones.2 Among these 58 million people, 25 million report having limited English proficiency (LEP).1 These individuals have difficulty speaking, reading, writing, or understanding English,3 which presents significant obstacles to accessing and receiving care in an English-dominant healthcare system. Due to language barriers, LEP patients have worse healthcare quality and outcomes4–7 and decreased access to preventive services8, 9 and cancer screening.10–13 Although federal regulations require healthcare organizations to provide trained interpreters for LEP patients, many hospitals and clinicians are non-compliant with these regulations, leading to persistent inequities in care.14 Language concordance, when a physician is fluent in a patient’s preferred language, offers a way of reducing these disparities.

Health disparities due to language barriers are reduced when care is provided by language-concordant clinicians. For example, studies demonstrate that LEP patients with language-concordant physicians report receiving more education about their care, have fewer unasked questions, and have better medication adherence and fewer emergency room visits.15–17 When a clinician and an LEP patient communicate in a language in which only one of them is fluent, this partial language concordance can further obfuscate clinical interactions by leading patients and providers to believe they understand each other, thus contributing directly and indirectly to medical errors and poor outcomes.14, 18 While communicating in a patient’s native language may build rapport, non-fluent clinicians must know when to call an interpreter19 and have an accurate gauge of their own limitations.14, 20 Patient satisfaction with care is higher, adherence to medications is better, and patients have fewer unanswered questions about their care when language-concordant care is provided.15, 16, 21 However, there is also evidence that language concordance is associated with lower cancer screening rates for patients with LEP.17, 22 Given these divergent findings, it is important to determine the overall impact of language concordance in clinical settings.

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the data on the impact of language-concordant care for LEP patients compared to other interventions to improve language access, including professional interpreters and untrained (ad hoc) interpreters. We hypothesized that language-concordant care would be beneficial to LEP patients. Our goal was to create a comprehensive picture of the relationship between language concordance and quality of care for patients with LEP.

METHODS

Literature Search and Data Sources

We searched 5 databases for this systematic review: PubMed (NLM, 1945 to October 2017), PsycINFO (OVID, 1806 to October 2017), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters, 1945 to October 2017), Cochrane Library (Wiley, 1966 to October 2017), and EMBASE (Elsevier, 1966 to October 2017). Two authors (LCD and KM, a research librarian) developed strategies to find relevant articles. Online Appendix 1 provides detailed search strategies for each database. We did not apply limits to date or article language. The Endnote (Thomson Reuters) bibliographic citation management program was used to manage the citations and remove duplicates.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

A systematic title and abstract review was conducted by two authors (KI and LD) using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework.23 Qualitative articles that systematically gathered data on language-concordant interventions were also eligible for inclusion. Articles were eliminated without further review if they did not focus specifically on the impact of language-concordant care and clinical outcomes. Because of heterogeneity in the methods and outcomes, we pooled our results using qualitative rather than quantitative approaches.

Data Abstraction

Two authors abstracted data from the remaining 33 articles independently (LD and KI or DC). We abstracted 16 items from each article: study locations, sample sizes, type of clinical outcomes studied, participants’ ages (including range, mean, and standard deviation if provided), participants’ race and/or ethnicity, languages interpreted, type of patient navigators, study designs, recruitment methods, facility types, comparison groups, and outcomes and results/major findings. One author (LD) reviewed all abstractions and registered any discrepancy between authors. These discrepancies were resolved by consensus. For studies with more than one outcome, we categorized outcomes based on the best result (e.g., if one outcome was better for patients with language-concordant physicians and another showed no difference, we categorized the study as demonstrating better outcomes for language-concordant care).

RESULTS

Study Selection

Our search yielded 8618 citations. After adding 5 articles identified from other sources and removing duplicates and exclusion of articles that were not relevant, 126 articles remained for full-text review. Of these, 92 were excluded yielding 34 articles. During full-text review, one additional article was eliminated because it was a descriptive study of a language concordance intervention for which there were no patient outcomes described.24 A total of 33 articles were included in our qualitative analysis. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram.25

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Quality Appraisal

We systematically appraised the quality of all articles using the Downs and Black checklist.26–28 For this review, the modified Downs and Black was used.29 Online Appendix 2 shows the Downs and Black checklist components for each article. To assess the quality of the language services provided, the authors also abstracted information to describe any language proficiency testing clinicians received, if documented in the study. The quality of the articles overall was very good, with some variation. This was due, in part, to incomplete information from some of the included articles.

Study Characteristics

Of the 33 articles, 4 (6.9%) were randomized controlled trials and the remaining 29 (87.9%) were cohort studies. The 33 studies were grouped by the outcome measure studied, including quality of care (further subdivided into primary care, diabetes care, pain management, cancer, and hospital setting), satisfaction with care/communication, medical understanding, and mental health, as shown in Table 1. The USA was the setting of 94% of the studies (31/33). Seventy-six percent (25/33) focused on interventions for Spanish-speaking patients and 30% (10/33) for speakers of Asian languages.

Table 1.

Description of Articles

| Author | Study design | N | Female (%) | Age (range) | Languages | Setting | Interventions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of care: primary care | ||||||||

| Ahmed (2015), UK30 | Cohort study | 190,582 | 55.2 | Bengali, Hindi, Urdu | Primary care | Language concordance vs. English-speaking persons | Patient experience | |

| Arauz (2010), USA31 | Cohort study | 462 | 86 | Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant provider vs. no language-concordant provider (without interpreter) | Quality of care | |

| Clark (2004), USA32 | Cohort study | 454 | 67 | 48 (18–85) | Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant provider vs. no language-concordant provider (without interpreter) | Patient agreement about physicians’ recommendations for patient health behavior (e.g., diet, exercise, medication, smoking, stress, and weight) |

| Eamranond (2009), USA33 | Cohort study | 306 | 63 | 51.8, 54.1 | Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant provider vs. interpreter | Counseling on diet and exercise |

| Eamranod (2011), USA17 | Cohort study | 306 | 63 | 51.8, 54.1 | Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant provider vs. no language-concordant provider (without interpreter) | Rates of screening for hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cervical cancer, colorectal, and breast cancer screening |

| Gonzalvo (2016), USA34 | Cohort study | 71 | Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant care vs. English-speaking persons | Hemoglobin A1C (HbAIc), LDL, and blood pressure | ||

| Jih (2015), USA35 | Cohort study | 4821 | 55 | 52.9, 53.9, 61.1, 62.1 | Korean; Vietnamese; Cantonese; Mandarin; Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant care vs. usual care | Use of cancer screening and flu vaccines |

| Linsky (2010), USA22 | Cohort study | 23, 297 | 57 | (50–85) | Asian languages combined; Spanish | Primary care | Language-concordant care vs. usual care vs. English-speaking persons | Colorectal cancer screening rates |

| Martin (2009), USA36 | Cohort study | 20, 052 | Unspecified | Primary care | Race/ethnic, gender, and/or language-concordant provider vs. racial/ethnic, gender, and/or language-discordant provider | Access to and utilization of primary care | ||

| Quality of care: diabetes | ||||||||

| Diamond (2010), USA37 | Cohort study | 5994 | Spanish, Chinese languages combined, other | Diabetes | Language-concordant provider vs. no language-concordant provider (without interpreter) | HbA1c, LDL, blood pressure, foot exams for diabetic patients | ||

| Fernandez (2011), USA38 | Cohort study | 6738 | 45 | Spanish | Diabetes | Language-concordant provider vs. no language-concordant provider (with or without interpreter) vs. English-speaking persons | Glycemic control | |

| Mehler (2004), USA39 | Cohort study | 55 | 58.2 | (30–79) | Russian | Diabetes | Language and culturally concordant provider vs. usual care | Glycemic, lipid, blood pressure control |

| Parker (2017), USA40 | Randomized controlled trial | 1605 | 55 | Spanish | Diabetes | Language-concordant providers vs. language-discordant providers | Glycemic control | |

| Traylor (2010), USA41 | Cohort study | 131,277 | Spanish | Diabetes | Patients receiving care from a race and/or language-concordant provider vs. patients receiving care from a race and/or language-discordant provider | Adherence to CVD medications for diabetic patients | ||

| Quality of care: pain management | ||||||||

| Chiauzzi (2011), USA42 | Cohort study | 187 | Spanish | Pain management | Unspecified | Use of established pain management practices | ||

| Quality of care: cancer | ||||||||

| Kim (2015), USA43 | Randomized controlled trial | 224 | Chinese (unspecified) | Cancer care | Language and ethnically concordant provider vs. language and ethnically discordant vs. language-discordant but ethnically concordant with interpreter vs. language and ethnically discordant provider with interpreter | Return of fecal occult blood test (FOBT) | ||

| Polednak (2007), USA44 | Cohort study | 1874 | 53 | Spanish | Cancer care | Spanish-language practice vs. usual care | Receipt of radiotherapy in breast and prostate cancer | |

| Quality of care: hospital setting | ||||||||

| Grover (2012), USA45 | Cohort study | 1196 | 46 | Spanish | ED care | Language-concordant provider vs. telephonic interpreter vs. in-person interpreter | ED throughput times | |

| Jacobs (2007), USA46 | Cohort study | 323 | 52 | Spanish | ED care | Language-concordant provider vs enhanced interpreter services vs. usual interpreter services vs. English-speaking patients | Patient satisfaction, hospital length of stay, number of inpatient consultations and radiology tests conducted in the hospital, adherence with follow-up appointments, use of emergency department (ED) services and hospitalizations in the 3 months after discharge, and the costs associated with provision of the intervention and any resulting change in health care utilization | |

| Rayan (2014), Israel47 | Cohort study | 92 | 43 | 59.3 | Hebrew, Russian, Arabic | Inpatient | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider | Quality of transition of care between hospital and primary care |

| Satisfaction with care/communication | ||||||||

| Baker (1998), USA48 | Cohort study | 457 | 68 | Spanish | Language-concordant providers vs. language-discordant providers with and without interpreter | Satisfaction with the provider’s friendliness, respectfulness, concern, ability to make the patient comfortable, and time spent for the exam | ||

| Eskes (2013), USA49 | Cohort study | 100 | 83.8 | Spanish | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider (without interpreter) | Patient satisfaction | ||

| Fernandez (2004), USA50 | Cohort study | 116 | 81 | 59 | Spanish | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider (without interpreter) | Interpersonal processes of care scores | |

| Gany (2007), USA51 | Randomized controlled trial | 1276 | 51 | Cantonese, Mandarin, Spanish | Interpersonal care | Language-concordant provider vs. different interpreter methods | Patient satisfaction with communication and care | |

| Green (2005), USA21 | Cohort study | 2715 | 84 | Vietnamese; Cantonese; Mandarin | Interpersonal care | Language-concordant provider vs. interpreter | Patient satisfaction with communication and care | |

| Jaramillo (2016), USA52 | Cohort study | 156 | Spanish | Interpersonal care | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider with interpreters vs. English speakers | Patient question-asking behavior, communication, trust, perceived discrimination | ||

| Ngo-Metzger (2007), USA15 | Cohort study | 2746 | 67 | Chinese; Vietnamese; Cantonese; Mandarin | Interpersonal care | Language-concordant providers vs. usual care | Degree of health education, quality of interpersonal care, patient satisfaction | |

| Villalobos (2015), USA53 | Cohort study | 458 | 84.1 | 41.35 | Spanish | Interpersonal care | Language-concordant providers vs. language-discordant providers | Therapeutic alliance, quality of communication |

| Medical understanding | ||||||||

| Baker (1996), USA54 | Cohort study | 530 | Spanish | Interpersonal care | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider (with or without interpreter) | Self-perceived understanding of diagnosis and treatment, objective knowledge of discharge instructions | ||

| Wilson (2005), USA55 | Cohort study | 1200 | 58 | Armenian; Cambodian; Cantonese; Farsi; Hmong; Korean; Mandarin; Mien; Russian; Spanish; Tagalog; Vietnamese | Medical understanding | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider vs. English-proficient persons | Medical comprehension | |

| Mental health | ||||||||

| August (2011), USA56 | Cohort study | 2960 | 53 | Spanish; Asian languages combined | Mental health | Language-concordant provider vs. language-discordant provider vs. English-speaking persons | Perceived mental health needs and discussion of those needs with a provider | |

| Goncalves (2013), USA57 | Cohort study | 1328 | 73.3 | Portuguese | Mental health | Language-concordant provider vs. usual care | Adequacy of mental healthcare and use of the emergency department | |

| Marcos (1973), USA24 | Randomized controlled trial | 10 | 40 | (21–42) | Spanish | Mental health | Language-concordant providers vs. language-discordant providers without interpreter | Mental health diagnosis, psychopathology reported |

Language Concordance Outcomes

Seventy-six percent (25/33) of the studies demonstrated that at least one of the outcomes assessed was better for patients receiving language-concordant care, while 15% (5/33) of studies demonstrated no difference in outcomes, and 9% (3/33) studies demonstrated worse outcomes in patients receiving language-concordant care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Outcomes

| Author | Outcomes | Data source | Results | Overall impact of language concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of care: primary care | ||||

| Ahmed (2015), UK30 | Patient experience | National General Practice Patient Survey | Availability of a language-concordant physician: | Better patient experience |

| - Had the largest effect on communication ratings for Bangladeshis and the least for Indian respondents (p < 0.01) | ||||

| - Experience was not worse than, and maybe was better than, experience of White British patients | ||||

| - (+ 4.5; 95%CI − 1.0, + 10.1) | ||||

| Absence of language-concordant physician: | ||||

| - Worse experience reported by Bangladeshi (− 3.3, 95%CI − 4.6, − 2.0) and Pakistani (− 2.7, 95%CI − 3.6, − 1.9) respondents compared to White British | ||||

| Arauz (2010), USA31 | Quality of care | Promoting Healthy Development Survey | Latino parents in language-concordant patient–provider relationships: | No difference in quality of care |

| - Did not report higher-quality well-child care (p value not reported) | ||||

| For LEP patients of providers who self-rated as highly effective in treating Latino patients: | ||||

| - Parents reported higher quality of care in the domains of: | ||||

| ○ Family-centered care (mean 80.5 vs. 70.6; p = 0.02) | ||||

| ○ Helpfulness of care (mean 84.2 vs. 67.9; p = 0.02) | ||||

| Clark (2004), USA32 | Patient agreement about physicians’ recommendations for patient health behavior (e.g., diet, exercise, medication, smoking, stress, and weight) | Observation, interviews using locally developed questionnaire | Language concordance: | Higher patient–physician agreement about exercise but not medication counseling |

| - Positively influenced the likelihood of agreement about exercise (estimated regression coefficient 0.67, p < 0.05) | ||||

| - Negatively influenced agreement about medications (− 0.53, p < 0.1) | ||||

| - No difference in agreement on physician recommendations about stress, diet, smoking, and weight | ||||

| Eamranod (2009), USA33 | Counseling on diet and exercise | Medical record review | Patients with language-concordant physicians: | Increased likelihood of diet and exercise counseling |

| - More likely to be counseled on | ||||

| ○ Diet (odds ratio (OR) = 2.2, CI 1.3–3.7) | ||||

| ○ Physical activity (OR = 2.3, CI 1.4–3.8) | ||||

| ○ No significant difference with regard to discussion of smoking (OR = 1.3, CI 0.8–2.1) | ||||

| Eamranod (2011), USA17 | Rates of screening for hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cervical cancer, colorectal, and breast cancer screening | Medical record review | Patients in the language-concordant group were: | Lower rates of colorectal cancer screening, no difference in screening for hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cervical, or breast cancer |

| - Less likely to be screened for colorectal cancer compared with the language-discordant group, risk ratio 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.61–0.99) | ||||

| - No difference in the rates of screening for hyperlipidemia, diabetes, cervical cancer, and breast cancer compared to language-discordant group | ||||

| Gonzalvo (2016), USA34 | Hemoglobin A1C (HbAIc), LDL, and blood pressure | Medical record review | Compared to English-speaking patients, patients with a language-concordant provider had no significant difference in: | No difference in hemoglobin A1C, LDL, or blood pressure |

| - Hemoglobin A1C (1.25 vs. 1.16, p = 0.975) | ||||

| - LDL (15 vs. 20, p = 0.518) | ||||

| - Systolic blood pressure (2 vs. 4, p = 0.674) | ||||

| - Diastolic blood pressure (2 vs. 5, p = 0.431) | ||||

| Jih (2015), USA35 | Use of cancer screening and flu vaccines | California Health Interview Survey | Receipt of language-concordant care: | No difference in use of cancer screening and flu vaccines |

| - Did not facilitate mammography use (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72, 1.45) for Latinas or Asian women (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.27, 1.09) | ||||

| - Lowered odds of colorectal cancer screening among Asians but not Latinos (Asian AOR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.29, 0.86; Latino AOR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.56, 1.28) | ||||

| - Influenza vaccination rates did not differ between groups for either Latinos or Asians | ||||

| Linsky (2010), USA22 | Colorectal cancer screening rates | Medical Expenditures Panel Survey | LEP patients receiving language-concordant care had: | Lower colorectal cancer screening rates |

| - Lower rates of screening (adjusted OR, 0.57: 95% CI, 0.46–0.71) | ||||

| LEP patients receiving standard care had similar outcomes (adjusted OR 0.84: 95% CI, 0.58–1.21) to English-speaking patients | ||||

| Martin (2009), USA36 | Access to and utilization of primary care | Medical Expenditures Panel Survey | Compared to patients with language-discordant providers, patients with language-concordant providers: | Better access to primary care |

| - Had less difficulty contacting their usual source of care by telephone (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.0–3.5) | ||||

| - Did not find it difficult to contact the USC after hours (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.02–3.86) | ||||

| - No difference in coordination, longitudinality, or comprehensiveness of care outcomes | ||||

| Quality of care: diabetes | ||||

| Diamond (2010), USA37 | HbA1c, LDL, blood pressure, foot exams for diabetic patients | Medical record review | Patients with a language-concordant physician had no significant associations with any of the DM quality measures. | No difference in diabetes measures |

| Numbers not reported in this published abstract | ||||

| Fernandez (2011), USA38 | Glycemic control | Diabetes Study of Northern California Survey, medical record review | LEP patients with language-concordant physicians were less likely than LEP patients with language discordant physicians: | Better glycemic control |

| - To have poor glycemic control (16.1% vs. 27.8%, p = 0.02) | ||||

| Comparing LEP Latinos with language-concordant physicians and Latino English speakers: | ||||

| - Similar odds of poor glycemic control (OR 0.89; CI 0.53–1.49) | ||||

| LEP Latinos with language-discordant physicians had: | ||||

| - Greater odds of poor control than Latino English speakers (OR 1.76; CI 1.04–2.97) | ||||

| Among LEP Latinos, having a language-discordant physician: | ||||

| - Associated with significantly poorer glycemic control (OR 1.98; CI 1.03–3.80). | ||||

| Mehler (2004), USA39 | Glycemic, lipid, blood pressure control | Medical record review | Language-concordant care led to: | Better glycemic control, LDL cholesterol, and diastolic blood pressure; no change in systolic blood pressure |

| - Decreased hemoglobin A1c levels (from 8.4 to 8.0%, p = .007) | ||||

| - Decreased LDL cholesterol by 20% (from 126 to 102 mg/dl, p = 0.0002) | ||||

| - Decreased diastolic blood pressure (from 82.7 to 76.3 mmHg, p = 0.0002) | ||||

| - Decreased systolic blood pressure (from 143.2 to 140.6 mmHg, n.s.) | ||||

| Parker (2017), USA40 | Glycemic control, LDL control, systolic BP control | Medical record review; Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and American Diabetes Association guidelines | LEP Latinos who switched from language-discordant PCPs to language-concordant PCPs: | Better glycemic control, LDL control; no difference in systolic BP control |

| - Had a 10% (95% CI, 2 to 17%; p = 0.01) net increase in the prevalence of good glycemic control | ||||

| - Had a − 4% (95% CI, − 10 to 2%; p = 0.16) net decrease in the prevalence of poor control | ||||

| - Had an increase in the prevalence of LDL control (LDL < 100 mg/dl) by 9% (95% CI, 1 to 17%; p = 0.03) | ||||

| - No evidence of significant differences in changes in SBP control by concordance status | ||||

| Traylor (2010), USA41 | Adherence to cardiovascular medications for diabetic patients | Kaiser Permanente member surveys, diabetes registry surveys, medical record review | Spanish-speaking patients were less likely than English-speaking patients to be in good adherence: | Higher adherence to cardiovascular disease medication for diabetic patients |

| - Adherence to glucose-lowering medications (76% vs. 82%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - Adherence to lipid lowering medications (77% vs. 81%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - Adherence to blood pressure-lowering medications (79% vs. 82%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - Adherence to all cardiovascular disease medications (51% vs. 57%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Spanish-speaking patients with language-concordant providers had: | ||||

| - Higher rates of medication adherence (51% vs. 45%, p < 0.05) | ||||

| Quality of care: pain management | ||||

| Chiauzzi (2011), USA42 | Use of established pain management practices | Locally developed survey | Clinicians more likely to adhere to established pain management practices with Latino pain patients if they: | Increased likelihood of using established pain management practices |

| - Were fluent in Spanish | ||||

| - Had experience with Hispanic pain patients | ||||

| Numbers not reported in this published abstract | ||||

| Quality of care: cancer | ||||

| Kim (2015), USA43 | Return of fecal occult blood test (FOBT) | Locally developed survey | LEP patients attended an education session with an ethnically and language-concordant provider vs. a racially concordant provider speaking English with an interpreter vs. an English-speaking group of White patients | Lower return of FOBT in the language-concordant group but higher in the interpreted group |

| - The racially and language-concordant group had the lowest return rate, 49% vs. 61%, compared to the White and English-speaking presenter group and interpreter group (p = 0.01) | ||||

| - The interpreter group had a return rate of 72% vs. 61% in the White English-speaking group (p = 0.01) | ||||

| - In the multivariable model, the interpreter group was almost 3 times as likely to return their FOBT test as the other groups (OR 2.906 (1.359–6.214)) | ||||

| - After adjusting for changes in belief and intention to screen after the education session, participants in the interpreter group remained 2 times more likely to return their FOBT (2.716 (1.253–5.887)) | ||||

| Polednak (2007), USA44 | Receipt of radiotherapy in breast and prostate cancer | Connecticut Tumor Registry | LEP patients being seen at Spanish-language practice were: | Greater likelihood of receipt of radiotherapy for breast cancer; no difference for prostate cancer |

| - More likely to receive radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer (OR 2.35 (1.20–4.59)) | ||||

| - No significant different difference in receipt of radiotherapy for prostate cancer (OR 0.94 (0.53–1.67)) | ||||

| Quality of care: hospital setting | ||||

| Grover (2012), USA45 | Emergency department throughput times | Medical record review, interviews | Language-concordant providers had: | Longer emergency department throughput times |

| - Significantly longer throughput times (153 min) compared to the in-person interpreter group (116 min) and telephone interpreter group (141 min); p < 0.0001 | ||||

| - Difference was due to a difference in time seen by provider to disposition | ||||

| Jacobs (2007), USA46 | Patient satisfaction, hospital length of stay, number of inpatient consultations and radiology tests conducted in the hospital, adherence with follow-up appointments, use of emergency department (ED) services, and hospitalizations in the 3 months after discharge | Medical record review, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (H-CAHPS) | Having a language-concordant attending physician: | Increased satisfaction with care, fewer ED visits after discharge; no difference in length of stay, number of consultation and radiology tests, or hospitalizations after discharge |

| - Positively impacted LEP patients’ satisfaction with their physician (OR 0.42 (0.03, 0.81)) and their hospital stay (OR 0.55 (0.12, 0.99)) compared to receiving care through the enhanced interpreter services | ||||

| - Had no impact on utilization outcomes, except that it reduced the number of ED visits 3 months after discharge from 0.166 visits/patient for the language-discordant patients to 0.034 visits/patient for the language-concordant groups (p = 0.03) | ||||

| Rayan (2014), USA47 | Quality of transition of care between hospital and primary care | Care Transition Measure (CTM) score, locally developed survey | Patient–provider language concordance: | Better quality transition between hospital and primary care |

| - Was seen in 49% of minority patients’ discharge briefings | ||||

| - Was associated with higher CMT (64.1 in language-concordant vs. 49.8 in non-language-concordant discharges, p < 0.001) | ||||

| Satisfaction with care/communication | ||||

| Baker (1998), USA48 | Satisfaction with the provider’s friendliness, respectfulness, concern, ability to make the patient comfortable, and time spent for the exam | Interviews, locally developed survey | LEP patients with a language-concordant clinician (compared to those who used an interpreter): | Higher satisfaction with interpersonal care |

| - Rated their providers as more friendly (46% vs. 28%, p = 0.003) | ||||

| - Rated their provider as more respectful (47% vs. 28%, p = 0.002) | ||||

| - Rated their provider as more concerned with the patient as a person (39% vs. 16%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - Rated their provider as more likely to make the patient feel comfortable (34% vs. 13%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - No significant difference in perceived time spent (32% vs. 22%, p = 0.15) | ||||

| Eskes (2013), USA49 | Patient satisfaction | Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) | Patients with language-concordant providers: | Higher satisfaction with care |

| - Had higher satisfaction if their providers spoke Spanish (97% vs. 3%) | ||||

| - Reported that it mattered that their provider spoke Spanish fluently (83.7% vs. 16.3%) | ||||

| - Those more satisfied with fluency were also less likely to speak English (p = 0.001), understand English (p < 0.001), or have a high school diploma (p = 0.002) | ||||

| Fernandez (2004), USA50 | Interpersonal processes of care scores | Locally developed survey | LEP patients with language-concordant physicians: | Higher interpersonal processes of care scores |

| - Having greater language fluency was strongly associated with optimal interpersonal processes of care scores in the domain of elicitation of and responsiveness to patients, problems and concerns (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR), 5.25; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.59 to 17.27) | ||||

| - Higher score on a language–culture summary scale was associated with three IPC domains: | ||||

| 1. Elicitation/responsiveness (AOR, 6.34; 95% CI, 2.1 to 19.3) | ||||

| 2. Explanation of condition (AOR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.0 to 7.34) | ||||

| 3. Patient empowerment (AOR, 3.13; 95% CI, 1.2 to 8.19) | ||||

| 4. Not associated with two more-technical communication domains | ||||

| Gany (2007), USA51 | Patient satisfaction with communication and care | Locally developed survey | LEP patients with language-concordant providers compared to two interpreter interventions reported: | Higher comprehension and patient satisfaction with care |

| - More comprehension (59% vs. 39% and 35%, p < 0.05) | ||||

| - More satisfaction (mean composite score 0.628 vs. 0.436 and 0.538, p < 0.05) | ||||

| Green (2005), USA21 | Patient satisfaction with communication and care | Locally developed survey | Compared to LEP patients with language-concordant providers, patients receiving care through interpreters were: | Fewer unanswered questions about care, no difference in satisfaction with care |

| - More likely to report having questions about their care (30.1% vs 20.9%, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - More likely to report having questions about mental health (25.3% vs. 18.2%, p = 0.005) | ||||

| - No difference in how much time providers allowed them to explain the reason for their visit, explained things in a way that they could understand, and gave them as much information about their health and treatment as they wanted | ||||

| - Patients in the two groups also reported that the care they received was excellent or very good at similar rates | ||||

| Jaramillo (2016), USA52 | Patient question-asking behavior, communication, trust, perceived discrimination | Observation, locally developed survey | Compared to the English-speaking group, the Spanish language-concordant group: | Greater comfort with asking questions; higher communication scores; higher trust and lower perceived discrimination (compared to English speakers) |

| - Asked a similar number of questions (p = 0.9) | ||||

| - Both groups asked more questions compared to the Spanish-discordant participants (p = 0.002 and p = 0.001) | ||||

| - Language-concordant participants rated higher scores of communication (p = 0.03) | ||||

| - Increased preference for, and value of, language-concordant care | ||||

| - Spanish speakers in language-concordant and language-discordant groups significantly better trust and lower perceived discrimination scores compared to English-speaking families (p < 0.001; p = 0.001) | ||||

| - Language-discordant participants reported that they desired to ask more questions but were limited by a language barrier (p = 0.001) | ||||

| Ngo-Metzger (2007), USA15 | Degree of health education, quality of interpersonal care, patient satisfaction | Locally developed survey | LEP patients with language-discordant providers: | More health education; higher ratings of interpersonal care and satisfaction |

| - Received less health education (β = 0.17, p < 0.05) compared to those with language-concordant providers (use of an interpreter mitigated this disparity) | ||||

| - Reported worse interpersonal care (β = 0.28, p < 0.05) (use of interpreter exacerbated disparity) | ||||

| - Were more likely to give a low rating to their providers (OR 1.61; CI 0.97, 2.67) (use of interpreter exacerbated disparity) | ||||

| Villalobos (2015), USA53 | Therapeutic alliance, quality of communication | Locally developed survey, A Collaborative Outcomes Resource Network (ACORN) questionnaire, medical record review | LEP patients who saw a language-concordant provider: | Increased quality of communication; no difference in therapeutic alliance |

| - Had comparable satisfaction with LEP patients to those who saw an English-speaking provider with the aid of a trained interpreter | ||||

| Patients with a bilingual provider had similar therapeutic alliance ratings compared to those with an interpreter (mean 3.85 vs. 3.89) | ||||

| - Patients had a preference for language concordance | ||||

| - More likely to disclose personal health information with language-concordant provider | ||||

| Some numbers not provided for this study because it used qualitative methods for some of the above findings | ||||

| Medical understanding | ||||

| Baker (1996), USA54 | Self-perceived understanding of diagnosis and treatment, objective knowledge of discharge instructions | Locally developed survey | Patients with a language-concordant provider: | Better understanding of diagnosis |

| - Rated their understanding of their disease as good to excellent 67% of the time (vs. 57% of those who used an interpreter and 38% of those who thought an interpreter should have been used (p < 0.001)) | ||||

| - For understanding of treatment, numbers were 86% (language concordant) vs. 82% (interpreter used) vs. 58% (interpreter should have been used); p < 0.001 | ||||

| - When objective measures of understanding diagnosis and treatment were used, the differences between these groups were smaller and not statistically significant | ||||

| Wilson (2005), USA55 | Medical comprehension | Locally developed survey | LEP patients with language-concordant providers were: | Higher likelihood of reporting problems understanding a medical situation; no difference in confusion about medication use, trouble understanding labels, or a bad reaction to medications |

| - More likely than English-proficient patients to report problems understanding a medical situation (AOR 2.2/CI 1.2, 3.9) | ||||

| - No more likely than their English-proficient counterparts to report confusion about medication use, trouble understanding labels, or a bad reaction to medications | ||||

| LEP patients with language-discordant providers were: | ||||

| - More likely to report problems understanding a medical situation (AOR 9.4/CI 3.7, 23.8) | ||||

| - More likely to report difficulty understanding labels (AOR 4.2/CI 1.7, 10.3) | ||||

| - More likely to report bad medication reactions (AOR 4.1/CI 1.2, 14.7) | ||||

| Mental health | ||||

| August (2011)56 | Perceived mental health needs and discussion of those needs with a provider | California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) | LEP patients with language-concordant providers: | No difference in perception of mental health needs and discussion of mental health needs with provider |

| - Had no significant differences in their perceptions of their mental health needs (OR 2.24, 95% CI 0.32–15.71) | ||||

| - No difference in discussion of mental health needs with provider (OR 2.49, 95% CI 0.79–7.90) | ||||

| - But differences with race/language interaction term: | ||||

| - Spanish language-concordant Latinos were just as likely to discuss their mental health needs with their physicians as English language-concordant Latinos | ||||

| - Asian language-concordant Asian/Pacific Islanders were less likely to discuss their mental health needs with their physicians than English language-concordant Asian/Pacific Islanders | ||||

| Goncalves (2013)57 | Adequacy of mental healthcare and use of the emergency department | Medical record review | LEP patients receiving any contact from linguistically and culturally tailored setting: | Higher rate of receipt of adequate treatment for mental health |

| - Received adequate care, defined as eight mental health visits, at a rate of 58.5% compared to 28.1% of those in usual care | ||||

| - When defining adequate care as four visits with psychopharmacology, there was a 62.5% vs. 38.8% difference between the groups, with the language-concordant group showing a higher rate of adequate care | ||||

| Marcos (1973), USA24 | Mental health diagnosis, psychopathology reported | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, medical record review | Language-concordant group had (compared to language-discordant group): | Lower mean pathology recorded and lower BPRS scores |

| - Significantly lower mean total pathology score (65 out of 120 vs. 93 out of 120; t = 7.11, p < 0.001) | ||||

| - The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) mean scores were significantly lower for 7 of the 18 scales, with the scales for “tension,” “depressed mood,” “hostility,” “anxiety,” “emotional withdrawal,” and “somatic concern” demonstrating the greatest degree of difference | ||||

QUALITY OF CARE: PRIMARY CARE

Among the studies looking at quality of care in a primary care setting, 4 demonstrated that language concordance had a positive impact on one or more outcomes studied30, 32, 33, 36 (better patient experience, higher likelihood that patients would receive and agree with counseling on diet and physical activity, and better access to and utilization of primary care providers), and 3 showed no difference31, 35 (the rate of flu vaccines and mammography and reported quality of well-child care), while 2 demonstrated a negative effect of language-concordant care on an outcome17, 22 (lower colorectal screening rates in both studies).

Quality of Care: Diabetes

In the studies examining quality of care for diabetic patients, 3 showed that language concordance had a positive impact on an outcome38, 39, 41 (better glycemic control, significant reduction in LDL, blood pressure, and HbA1C, and higher rates of adherence to CVD medications) and 1 did not show a difference in outcomes37 (in blood pressure, LDL, or HbA1C).

QUALITY OF CARE: PAIN MANAGEMENT

There was 1 study examining quality of care in pain management,42 which found that Spanish fluency and level of experience with Hispanic/Latino patients with pain had an impact on implementation of established pain management practices, while treatment with opioids was more influenced by practical matters and beliefs (e.g., finances and addiction concerns) rather than provider factors.

QUALITY OF CARE: CANCER

In the studies examining quality of care for cancer patients, 1 study showed that the language-concordant intervention was associated with higher rates of radiation therapy following surgery for breast cancer but not for prostate cancer patients44 (where there was no statistically significant difference), and another study showed that language-concordant intervention resulted in higher rates of colorectal cancer screening (more participants returned the fecal occult blood test).

QUALITY OF CARE: HOSPITAL SETTING

In the 3 studies that examined quality of care in the hospital setting, 2 showed a positive impact of language concordance46, 47 (increased satisfaction with care, fewer ED visits upon discharge, better quality transition between the hospital and the outpatient setting) and 1 showed a negative outcome45 (longer ED throughput times).

Satisfaction with Care/Communication

The 8 studies looking at satisfaction with care and communication each showed at least one positive outcome15, 21, 48–52 (higher satisfaction with care, fewer questions about care, better health education, enhanced privacy, enhanced communication, and increased therapeutic alliance).

Medical Understanding

Of the 2 studies evaluating medical understanding, each showed a positive outcome54, 55 (better understanding of diagnosis and higher likelihood of reporting problems understanding a medical situation in medical understanding).

Mental Health

Among the 3 studies focusing on mental health, 2 showed a positive outcome24, 57 (higher rates of adequate treatment and lower rates of pathological symptoms identified), with 1 showing no difference in the perception of mental health needs and discussion of these needs with a provider.56

DISCUSSION

Overall, the results of this review support the notion that language-concordant care is associated with better outcomes for LEP patients. Of the 33 studies included, the majority demonstrated a positive impact of language-concordant care on at least one of the major outcomes studied. The positive findings identified included patient-reported measures, such as patient satisfaction and understanding of diagnosis,48, 49, 51 and objective measures, including glycemic control and blood pressure for diabetic patients.38–40 These results align with our initial hypothesis that language-concordant care leads to better outcomes for LEP patients but there remain contrasting findings that may indicate some unintended consequences of language concordance.

The positive effects of language concordance are widespread, though there are some areas where receiving care from a language-concordant provider may be particularly advantageous. The majority of studies related to patient satisfaction, utilization of and access to care, and self-perceived knowledge of diagnosis demonstrated that language-concordant care had a positive impact. Additionally, the majority of publications in which process measures (blood pressure, HbA1C, and LDL) were studied showed that there is an association between language-concordant care and better process measure values for LEP patients. Taken together, these findings indicate that language-concordant care is associated with satisfaction and empowerment among patients, potentially improving their relationships with their long-term providers and producing positive health outcomes.

There were 3 studies in which language concordance was associated with negative results for LEP patients.17, 22, 45 The findings of lower colorectal cancer screening rates and longer ED throughput times for patients receiving language-concordant care may be a product of study design, or could reflect unanticipated impacts of language-concordant care that need to be taken into account by researchers and policy makers. In the context of the studies on language-concordant care in the hospital setting, which indicates higher quality of care, better patient satisfaction, and fewer subsequent ED visits for patients seen in the ED by language-concordant providers, the longer ED throughput times could be a result of providers taking more time with patients and providing better quality of care, and thus, the longer ED throughput times should not necessarily be seen as a negative outcome. The lower rates of colorectal screening that 2 studies demonstrated17, 22 may be the result of better elucidation of the risks of colorectal cancer screening by language-concordant providers, which could lead some patients to opt out of the procedure based on an improved understanding. It may also reflect a patient–provider dynamic where LEP patients have more autonomy in making healthcare decisions. It is also possible that the providers considered to be language concordant in these studies were not truly fluent in their patients’ preferred languages. There was no assessment of the clinicians’ non-English language abilities in any of the studies demonstrating lower rates of colorectal cancer screening. These findings may reflect partial language concordance and poor quality of communication around colorectal cancer screening. The studies demonstrating longer ED throughput times and lower rates of colorectal cancer screening warrant future research to understand the underlying reasons for the findings before it is concluded that they are indicative of inferior patient care.

Although the findings of this review are consistent with previous research in demonstrating the overall positive impact of language concordance, there are limitations that must be addressed. The quality of these studies, as appraised by the Downs and Black Checklist, was generally high, which lends validity to the findings of this review. However, very few of the included studies assessed the fluency of the language-concordant providers, a key variable impacting the relevance of each study’s findings. Without this information, we are left without knowing whether the quality of communication is comparable to that of an English-speaking patient–provider dyad (which often served as the comparison group). This relates to a larger issue in the landscape of patient–provider language concordance, which is that there is currently no standardized assessment of clinician language proficiency that is consistently used by healthcare facilities. If such an assessment were used and its results were reported in future studies, this data would further help in appraising the quality of the research. Another limitation of this review is the fact that most of the studies included were performed in or near major cities in the USA and in clinics or hospitals affiliated with academic medical centers, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other countries and healthcare settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the rapidly growing LEP population in the USA, efforts to improve quality of and access to care will be ineffective if they do not attempt to address the barriers faced by LEP patients. The findings of this review indicate that, in the vast majority of situations, language-concordant care improves outcomes. Almost all of the studies included were of good quality, but none provided a standardized assessment of provider language skills. In order to systematically evaluate the impact of truly language-concordant care on outcomes and draw meaningful conclusions, future studies must include an assessment of clinician language proficiency and longitudinal observational studies. Language-concordant care offers an important way for hospitals to meet the unique needs of their LEP patients.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 129 kb)

Funding Information

Dr. Diamond reported salary support from grants K07 CA184037 and P30 CA008748 from the National Cancer Institute and AD-1409-23627 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The authors received financial support from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center SCORE Program and Summer Medical Student Research Fellowship Program (P30 CA008748 and R25 CA020449).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. American FactFinder: US Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau. 2011.

- 2.Ryan C. Languages in the United States: 2011. US Census Bureau. 2013.

- 3.LEP.gov. Commonly askd questions and answers regarding Limited English Proficent (LEP) Individuals. 2011. Available from: http://www.lep.gov/faqs/faqs.html#One_LEP_FAQ. Accessed 15 Sept 2018

- 4.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Warton EM, Adler N, Moffet H, Schenker Y, et al. Language Barriers, Physician-Patient Language Concordance, and Glycemic Control Among Insured Latinos with Diabetes: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):170–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores G, Abreu M, Tomany-Korman SC. Limited English proficiency, primary language at home, and disparities in children's health care: how language barriers are measured matters. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(4):418. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kandula NR, Lauderdale DS, Baker DW. Differences in Self-Reported Health Among Asians, Latinos, and Non-Hispanic Whites: The Role of Language and Nativity. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2002;47(2):80–96. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derose KP, Baker DW. Limited English proficiency and Latinos’ use of physician services. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(1):76–91. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language Spoken and Differences in Health Status, Access to Care, and Receipt of Preventive Services Among US Hispanics. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):2021–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Med Care. 2002;40(1):52–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs EA, Karavolos K, Rathouz PJ, Ferris TG, Powell LH. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(8):1410–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites. Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):800–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond LC, Wilson-Stronks A, Jacobs EA. Do hospitals measure up to the national culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards? Med Care. 2010;48(12):1080–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f380bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, Greenfield S, Massagli MP, Clarridge B, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):324–30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988;26(12):1119–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198812000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eamranond PP, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Wee CC. Patient-physician language concordance and primary care screening among spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 2011;49(7):668–72. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215d803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prince D, Nelson M. Teaching Spanish to emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2(1):32–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regenstein M, Andres E, Wynia MK. Appropriate use of non-English-language skills in clinical care. JAMA. 2013;309(2):145–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.116984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond LC, Tuot DS, Karliner LS. The use of Spanish language skills by physicians and nurses: policy implications for teaching and testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):117–23. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1779-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green AR, Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Massagli MP, Phillips RS, Iezzoni LI. Interpreter services, language concordance, and health care quality. Experiences of Asian Americans with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1050–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linsky A, McIntosh N, Cabral H, Kazis LE. Patient-provider language concordance and colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):142–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1512-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcos LR, Alpert M, Urcuyo L, Kesselman M. The effect of interview language on the evaluation of psychopathology in Spanish-American schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1973;130(5):549–53. doi: 10.1176/ajp.130.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255–99. doi: 10.1177/1077558705275416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs E, Chen AH, Karliner LS, AGGER-GUPTA N, Mutha S. The need for more research on language barriers in health care: a proposed research agenda. Milbank Q. 2006;84(1):111–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehin R, Burnett R, Brasher P. Does the new generation of high-flex knee prostheses improve the post-operative range of movement? A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(10):1429–34. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.23199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed F, Abel GA, Lloyd CE, Burt J, Roland M. Does the availability of a South Asian language in practices improve reports of doctor-patient communication from South Asian patients? Cross sectional analysis of a national patient survey in English general practices. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:55. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0270-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arauz Boudreau AD, Fluet CF, Reuland CP, Delahaye J, Perrin JM, Kuhlthau K. Associations of providers' language and cultural skills with Latino parents’ perceptions of well-child care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(3):172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark T, Sleath B, Rubin RH. Influence of ethnicity and language concordance on physician-patient agreement about recommended changes in patient health behavior. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eamranond PP, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Wee CC. Patient-physician language concordance and lifestyle counseling among spanish-speaking patients. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(6):494–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalvo JD, Sharaya NH. Language Concordance as a Determinant of Patient Outcomes in a Pharmacist-Managed Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Clinic. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(2):103–5. doi: 10.1177/0897190014544790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jih J, Vittinghoff E, Fernandez A. Patient-physician language concordance and use of preventive care services among limited english proficient latinos and asians. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(2):134–42. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin BC, Shi L, Ward RD. Race, gender, and language concordance in the primary care setting. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2009;22(4):340–52. doi: 10.1108/09526860910964816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diamond L, Chung S, Palaniappan L, Luft HS. The effect of patient-physician racial/ethnic and language concordance on quality of diabetes care. J Gen Intern icine. 2010;25:S402. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Warton EM, Adler N, Moffet HH, Schenker Y, et al. Language barriers, physician-patient language concordance, and glycemic control among insured Latinos with diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):170–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehler PS, Lundgren RA, Pines I, Doll K. A community study of language concordance in Russian patients with diabetes. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(4):584–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker MM, Fernandez A, Moffet HH, Grant RW, Torreblanca A, Karter AJ. Association of Patient-Physician Language Concordance and Glycemic Control for Limited-English Proficiency Latinos With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):380–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1172–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiauzzi E, Black RA, Frayjo K, Reznikova M, Grimes Serrano JM, Zacharoff K, et al. Health care provider perceptions of pain treatment in Hispanic patients. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):267–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim K, Chandraskar E, Lam H. Colorectal cancer screening: Does racial/ethnic and language concordance matter? In: Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention Conference: 7th AACR Conference on the Science of Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved San Antonio, TX United States Conference Start: 20141109 Conference End: 20141112 Conference Publication: (varpagings) [Internet]. 2015;24(10 SUPPL. 1) (no pagination).

- 44.Polednak AP. Identifying newly diagnosed Hispanic cancer patients who use a physician with a Spanish-language practice, for studies of quality of cancer treatment. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(3):185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grover A, Deakyne S, Bajaj L, Roosevelt GE. Comparison of throughput times for limited English proficiency patient visits in the emergency department between different interpreter modalities. J Immigr Minor Health / Center Minor Public Health. 2012;14(4):602–7. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9532-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobs EA, Sadowski LS, Rathouz PJ. The impact of an enhanced interpreter service intervention on hospital costs and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):306–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0357-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rayan N, Admi H, Shadmi E. Transitions from hospital to community care: the role of patient-provider language concordance. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2014;3:24. doi: 10.1186/2045-4015-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 1998;36(10):1461–70. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eskes C, Salisbury H, Johannsson M, Chene Y. Patient satisfaction with language-concordant care. J Physician Assist Educ. 2013;24(3):14–22. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201324030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Rosenthal A, Stewart AL, Wang F, et al. Physician language ability and cultural competence. An exploratory study of communication with Spanish-speaking patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):167–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gany F, Leng J, Shapiro E, Abramson D, Motola I, Shield DC, et al. Patient satisfaction with different interpreting methods: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):312–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaramillo J, Snyder E, Dunlap JL, Wright R, Mendoza F, Bruzoni M. The Hispanic Clinic for Pediatric Surgery: A model to improve parent–provider communication for Hispanic pediatric surgery patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(4):670–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villalobos BT, Bridges AJ, Anastasia EA, Ojeda CA, Rodriguez JH, Gomez D. Effects of language concordance and interpreter use on therapeutic alliance in Spanish-speaking integrated behavioral health care patients. Psychol Serv. 2016;13(1):49–59. doi: 10.1037/ser0000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Coates WC, Pitkin K. Use and effectiveness of interpreters in an emergency department. J Am Med Assoc. 1996;275(10):783–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):800–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.August KJ, Nguyen H, Quyen NM, Sorkin DH. Language Concordance and Patient-Physician Communication Regarding Mental Health Needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(12):2356–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goncalves M, Cook B, Mulvaney-Day N, Alegria M, Kinrys G. Retention in mental health care of Portuguese-speaking patients. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50(1):92–107. doi: 10.1177/1363461512474622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 129 kb)