Abstract

Population-based study for predicting the prognosis for breast cancer liver metastasis (BCLM) is lacking at present. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate newly diagnosed BCLM patients of different tumor subtypes and assess potential prognostic factors for predicting the survival for BCLM patients. Specifically, data were collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program from 2010 to 2014, and were assessed, including the data of patients with BCLM. Differences in the overall survival (OS) among patients was compared via Kaplan-Meier analysis. Other prognostic factors of OS were determined using the Cox proportional hazard model. In addition, the breast cancer-specific mortality was assessed using the Fine and Gray's competing risk model. A nomogram was also constructed on the basis of the Cox model for predicting the prognosis of BCLM cases. A total of 2,098 cases that had a median OS of 20.0 months were included. The distribution of tumor subtypes was as follows: 42.2% with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2; -)/hormone receptor (HR; +), 12.8% with Her2(+)/HR(−), 19.1% with Her2(+)/HR(+) and 13.5% with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that older age (>64 years), unmarried status, larger tumor, higher grade, no surgery, metastases at other sites, and TNBC subtype were associated with shorter OS. Additionally, multivariate analysis revealed that older age (>64 years), unmarried status, no surgery, bone metastasis, brain metastasis and TNBC subtype were significantly associated with worse prognosis. Thus, age at diagnosis, marital status, surgery, bone metastasis, brain metastasis and tumor subtype were confirmed as independent prognosis factors from a competing risk model. We also constructed a nomogram, which had the concordance index of internal validation of 0.685 (0.650–0.720). This paper had carried out the population-based prognosis prediction for BCLM cases. The survival of BCLM differed depending on the tumor subtype. More independent prognosis factors were age at the time of diagnosis, surgery, marital status, bone metastasis, as well as brain metastasis, in addition to tumor subtype. Notably, the as-constructed nomogram might serve as an efficient approach to predict the prognosis for individual patients.

Keywords: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, breast cancer, liver metastases, survival analysis, tumor subtype

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) ranks as the top leading malignant tumors among females, and also accounts for the most common cause of tumor-related mortality in females worldwide (1–6). Approximately 20–30% of BC cases develop metastases (7), while, ~50% of patients will suffer from BC liver metastasis (BCLM) (8,9). The presence of liver metastasis has markedly worsened the prognosis of patients, and the median survival was reported to be 3.8–29 months (10–13).

However, several studies have previously summarized prognostic factors and survival outcomes associated with BCLM during the palliative treatment for metastasis (10–18). In addition, many previous studies have conducted analysis using a low number of patients receiving treatment in medical centers. Such studies have analyzed overall survival (OS) based on the conventional Cox proportional models, which is less reliable than the competing risk model.

Population-based epidemiological studies on clinical outcome predictors are lacking at present. The characteristics of patients, as well as the prognosis factors among patients have added to the difficulty in assessing the prognosis and treating patients, and thus needs further study. Therefore, the population-based prediction of prognosis for newly diagnosed BCLM is required for decision-making for the clinical treatment of BC.

A competing risk analysis was conducted in the present study to examine the association between tumor subtype and other prognostic factors, and the OS for BCLM cases collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program. Furthermore, nomograms were utilized to visualize the Cox regression models, and to predict the prognosis for cancer cases. Moreover, we constructed a convenient nomogram to assess survival.

Materials and methods

Study design

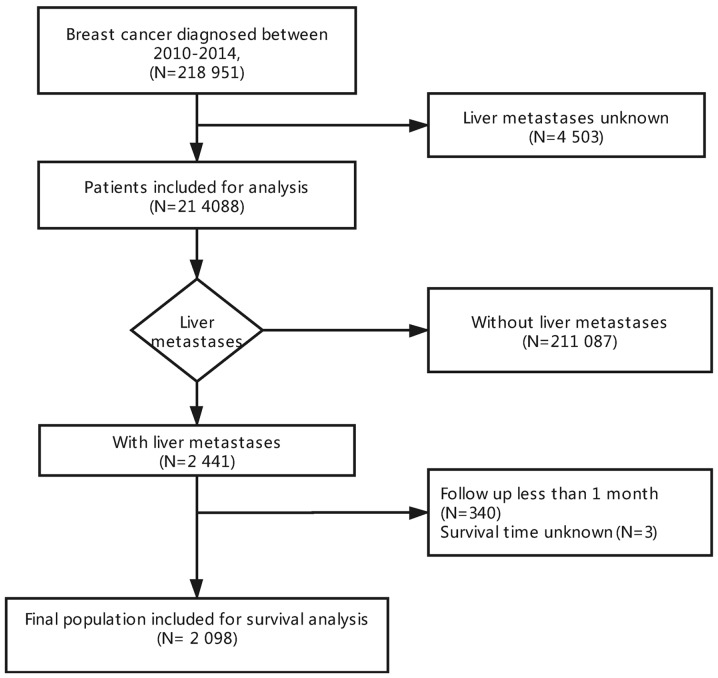

Data had been collected based on the SEER program, which had covered ~30% of the population of the United States of America. At present, SEER contains data regarding the treatment, incidence and survival of various types of cancer. We were approved to access the research data files (reference no. 16136-Nov2016), and data regarding with/without liver metastasis in newly diagnosed BC patients were collected from 2010 to 2014, since the metastatic sites at first diagnosis and molecular subtypes were available from 2010. A total of 218,951 cases diagnosed with BC from 2010 to 2014 were identified from the SEER database (https://seer.cancer.gov/). Patients with unknown liver metastasis status at the time of diagnosis were excluded from analysis (n=4,503), as a result, a cohort of 214,088 cases were enrolled for further analysis. Of note, 2,441 of these cases had been diagnosed with BCLM. Then, patients that were followed up for <1 month (n=340) or had unknown survival time (n=3) were excluded, leaving 2,098 patients eligible for survival analysis (Fig. 1). All parameters adopted in this paper had been identified from recent studies (19–23), which included the year of diagnosis, sex, age, marital status, race, tumor size, insurance status, tumor grade, laterality, nodal stage, surgery, site of metastasis, tumor subtype, cause of mortality, vital status, as well as months of survival. In addition, patients were stratified by the BC subtype as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2; -)/hormone receptor (HR; +), Her2(+)/HR(+), Her2(+)/HR(−), or triple-negative (TNBC). Patients were followed with a median of 12 months (1–59 months).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient selection.

In the present study, we did not enroll patients and the data collected from the SEER database did not contain personally identifiable information; therefore, informed consent was unnecessary. We obtained approval from the Ethical Committee and the Institutional Review Board of our University Cancer Center.

Statistical analysis

Baseline categorical variables were compared using a Fisher's exact test or χ2 test. OS had been selected as the primary endpoint, which was calculated as the duration from the diagnosis of BC to mortality from all causes or the final follow-up in censored cases. Differences in OS were evaluated through Kaplan-Meier analysis, followed by a log-rank test. Furthermore, the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was generated, and hazard ratios (HRs) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were subsequently computed. To evaluate BC-specific mortality, the Fine and Gray's competing risk model was adopted, since its eventual failure could be attributed precisely to cancer-associated mortality. Additionally, the nomogram was also constructed through the R project rms package (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms). In addition, model discriminating ability and stability had been computed using c-statistics and bootstrapping. Subsequently, calibration plots were generated for comparing the event rate among the population, as well as that estimated through the model for patients at some time. All tests were two-tailed; P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. STATA 12.0 (StataCorp LP) and R (version 3.4.1; R Foundation) were applied for all statistical analyses using the cmprsk package (version 2.2–7).

Results

Patient features

Data from a total of 2,098 patients with an initial diagnosis of BCLM from 2010 to 2014 were recruited for analysis in the presented study. The age of patients ranged from 24–99 years, with a median of 59 years. At the time of diagnosis, 571 (27.2%) cases exhibited metastasis only in the liver, while 799 (38.1%) also had bone metastases, 739 (35.2%) had concurrent lung metastases, while 190 (9.1%) had brain and liver metastases. A majority of cases were of stage III/IV (45.7%; n=959). In cases whose BC subtype was known, 42.2% (n=886) had Her2(−)/HR(+), 12.8% (n=268) had Her2(+)/HR(−), 19.1% (n=401) had Her2(+)/HR(+), and 13.5% (n=284) had TNBC (Table I).

Table I.

Patient characteristics according to tumor subtypes.

| Tumor subtypesa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Her2 -/HR+ | Her2 +/HR- | Her2 +/HR+ | Triple negative | Unknown | Total | ||||||||

| Patient characteristics | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value |

| All patients | 886 | 42.2 | 268 | 12.8 | 401 | 19.1 | 284 | 13.5 | 259 | 12.3 | 2,098 | 100.0 | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||||||||

| 2010 | 168 | 19.0 | 48 | 17.9 | 80 | 20.0 | 51 | 18.0 | 68 | 26.3 | 415 | 19.8 | 0.732 |

| 2011 | 184 | 20.8 | 58 | 21.6 | 72 | 18.0 | 55 | 19.4 | 53 | 20.5 | 422 | 20.1 | |

| 2012 | 181 | 20.4 | 53 | 19.8 | 103 | 25.7 | 61 | 21.5 | 47 | 18.1 | 445 | 21.2 | |

| 2013 | 192 | 21.7 | 57 | 21.3 | 72 | 18.0 | 59 | 20.8 | 52 | 20.1 | 432 | 20.6 | |

| 2014 | 161 | 18.2 | 52 | 19.4 | 74 | 18.5 | 58 | 20.4 | 39 | 15.1 | 384 | 18.3 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||

| <50 | 212 | 23.9 | 81 | 30.2 | 126 | 31.4 | 74 | 26.1 | 36 | 13.9 | 529 | 25.2 | <0.001b |

| 50–64 | 340 | 38.4 | 118 | 44.0 | 177 | 44.1 | 114 | 40.1 | 108 | 41.7 | 857 | 40.8 | |

| >64 | 334 | 37.7 | 69 | 25.7 | 98 | 24.4 | 96 | 33.8 | 115 | 44.4 | 712 | 33.9 | |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | 6 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 6 | 2.3 | 19 | 0.9 | 0.288 |

| Female | 880 | 99.3 | 267 | 99.6 | 397 | 99.0 | 282 | 99.3 | 253 | 97.7 | 2,079 | 99.1 | |

| Race | |||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 631 | 71.2 | 190 | 70.9 | 286 | 71.3 | 185 | 65.1 | 200 | 77.2 | 1492 | 71.1 | 0.010b |

| African descent | 157 | 17.7 | 50 | 18.7 | 72 | 18.0 | 77 | 27.1 | 41 | 15.8 | 397 | 18.9 | |

| Others | 94 | 10.6 | 28 | 10.4 | 43 | 10.7 | 22 | 7.7 | 17 | 6.6 | 204 | 9.7 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.2 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||||||

| Unmarried | 227 | 25.6 | 51 | 19.0 | 111 | 27.7 | 61 | 21.5 | 61 | 23.6 | 511 | 24.4 | 0.023b |

| Married | 605 | 68.3 | 207 | 77.2 | 267 | 66.6 | 206 | 72.5 | 184 | 71.0 | 1,469 | 70.0 | |

| Unknown | 54 | 6.1 | 10 | 3.7 | 23 | 5.7 | 17 | 6.0 | 14 | 5.4 | 118 | 5.6 | |

| Insurance status | |||||||||||||

| Uninsured | 28 | 3.2 | 3 | 1.1 | 21 | 5.2 | 13 | 4.6 | 17 | 6.6 | 82 | 3.9 | 0.025b |

| Insured | 840 | 94.8 | 262 | 97.8 | 373 | 93.0 | 265 | 93.3 | 232 | 89.6 | 1,972 | 94.0 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 2.0 | 3 | 1.1 | 7 | 1.7 | 6 | 2.1 | 10 | 3.9 | 44 | 2.1 | |

| Size (mm) | |||||||||||||

| ≤20 | 133 | 15.0 | 36 | 13.4 | 62 | 15.5 | 35 | 12.3 | 35 | 13.5 | 301 | 14.3 | 0.040b |

| 21–50 | 331 | 37.4 | 104 | 38.8 | 168 | 41.9 | 100 | 35.2 | 60 | 23.2 | 763 | 36.4 | |

| >50 | 243 | 27.4 | 83 | 31.0 | 102 | 25.4 | 108 | 38.0 | 49 | 18.9 | 585 | 27.9 | |

| Unknown | 179 | 20.2 | 45 | 16.8 | 69 | 17.2 | 41 | 14.4 | 115 | 44.4 | 449 | 21.4 | |

| Grade | |||||||||||||

| I | 72 | 8.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 6 | 1.5 | 3 | 1.1 | 10 | 3.9 | 92 | 4.4 | <0.001b |

| II | 340 | 38.4 | 59 | 22.0 | 118 | 29.4 | 37 | 13.0 | 33 | 12.7 | 587 | 28.0 | |

| III/IV | 289 | 32.6 | 168 | 62.7 | 218 | 54.3 | 216 | 76.1 | 68 | 26.3 | 959 | 45.7 | |

| Unknown | 185 | 20.9 | 40 | 14.9 | 59 | 14.7 | 28 | 9.9 | 148 | 57.1 | 460 | 21.9 | |

| Laterality | |||||||||||||

| Left | 438 | 49.4 | 139 | 51.9 | 207 | 51.6 | 148 | 52.1 | 109 | 42.1 | 1,041 | 49.6 | 0.972 |

| Right | 406 | 45.8 | 124 | 46.3 | 189 | 47.1 | 130 | 45.8 | 98 | 37.8 | 947 | 45.1 | |

| Bilateral, single primary | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.7 | 5 | 1.9 | 14 | 0.7 | |

| Unknown | 38 | 4.3 | 3 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.0 | 4 | 1.4 | 47 | 18.1 | 96 | 4.6 | |

| Nodal stage | |||||||||||||

| Node negative | 34 | 3.8 | 16 | 6.0 | 18 | 4.5 | 17 | 6.0 | 6 | 2.3 | 91 | 4.3 | 0.931 |

| Node positive | 281 | 31.7 | 114 | 42.5 | 160 | 39.9 | 129 | 45.4 | 35 | 13.5 | 719 | 34.3 | |

| Unknown | 571 | 64.4 | 138 | 51.5 | 223 | 55.6 | 138 | 48.6 | 218 | 84.2 | 1,288 | 61.4 | |

| Surgery | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 181 | 20.4 | 71 | 26.5 | 104 | 25.9 | 102 | 35.9 | 28 | 10.8 | 486 | 23.2 | <0.001b |

| No | 700 | 79.0 | 194 | 72.4 | 294 | 73.3 | 181 | 63.7 | 230 | 88.8 | 1,599 | 76.2 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 13 | 0.6 | |

| Liver metastases only | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 209 | 23.6 | 104 | 38.8 | 112 | 27.9 | 89 | 31.3 | 57 | 22.0 | 571 | 27.2 | <0.001b |

| No | 661 | 74.6 | 157 | 58.6 | 281 | 70.1 | 191 | 67.3 | 190 | 73.4 | 1,480 | 70.5 | |

| Unknown | 16 | 1.8 | 7 | 2.6 | 8 | 2.0 | 4 | 1.4 | 12 | 4.6 | 47 | 2.2 | |

| Bone metastases | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 285 | 32.2 | 130 | 48.5 | 145 | 36.2 | 147 | 51.8 | 92 | 35.5 | 799 | 38.1 | <0.001b |

| No | 587 | 66.3 | 132 | 49.3 | 246 | 61.3 | 133 | 46.8 | 152 | 58.7 | 1,250 | 59.6 | |

| Unknown | 14 | 1.6 | 6 | 2.2 | 10 | 2.5 | 4 | 1.4 | 15 | 5.8 | 49 | 2.3 | |

| Lung metastases | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 317 | 35.8 | 73 | 27.2 | 132 | 32.9 | 115 | 40.5 | 102 | 39.4 | 739 | 35.2 | 0.010b |

| No | 541 | 61.1 | 184 | 68.7 | 256 | 63.8 | 161 | 56.7 | 137 | 52.9 | 1,279 | 61.0 | |

| Unknown | 28 | 3.2 | 11 | 4.1 | 13 | 3.2 | 8 | 2.8 | 20 | 7.7 | 80 | 3.8 | |

| Brain metastases | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 69 | 7.8 | 25 | 9.3 | 33 | 8.2 | 38 | 13.4 | 25 | 9.7 | 190 | 9.1 | 0.042b |

| No | 779 | 87.9 | 235 | 87.7 | 348 | 86.8 | 237 | 83.5 | 207 | 79.9 | 1,806 | 86.1 | |

| Unknown | 38 | 4.3 | 8 | 3.0 | 20 | 5.0 | 9 | 3.2 | 27 | 10.4 | 102 | 4.9 | |

| Status | |||||||||||||

| Alive | 388 | 43.8 | 144 | 53.7 | 246 | 61.3 | 65 | 22.9 | 76 | 29.3 | 919 | 43.8 | <0.001b |

| Dead | 498 | 56.2 | 124 | 46.3 | 155 | 38.7 | 219 | 77.1 | 183 | 70.7 | 1,179 | 56.2 | |

| Cause of death | |||||||||||||

| Alive | 313 | 35.3 | 137 | 51.1 | 223 | 55.6 | 54 | 19.0 | 57 | 22.0 | 784 | 37.4 | <0.001b |

| Cancer | 535 | 60.4 | 122 | 45.5 | 169 | 42.1 | 227 | 79.9 | 197 | 76.1 | 1,250 | 59.6 | |

| Other | 38 | 4.3 | 9 | 3.4 | 9 | 2.2 | 3 | 1.1 | 5 | 1.9 | 64 | 3.1 | |

Patients of unknown statuses were excluded from the comparative analysis.

P<0.05. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor.

Patients had been distributed based on tumor subtype and differences in the whole population were significant. Patients who developed TNBC liver metastasis were associated with advanced tumor stage (P<0.001), increased risks of bone (P<0.001), lung (P<0.001) and brain metastases (P=0.042), higher rate of surgery (P<0.001), and reduced rate of small tumor size (P=0.040), and increased risk of mortality (P<0.001). By contrast, patients with Her2(+)/HR(−) only had a higher rate of liver metastasis (P<0.001).

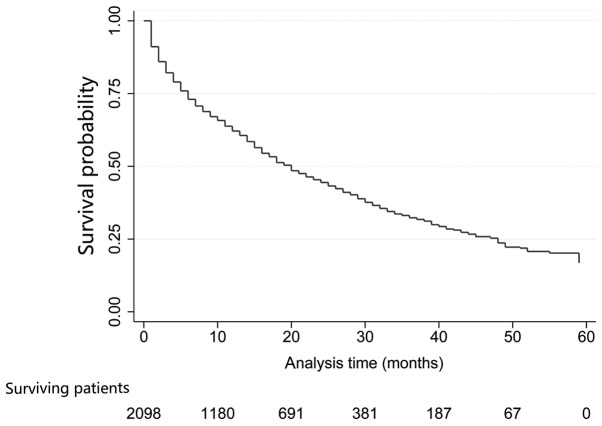

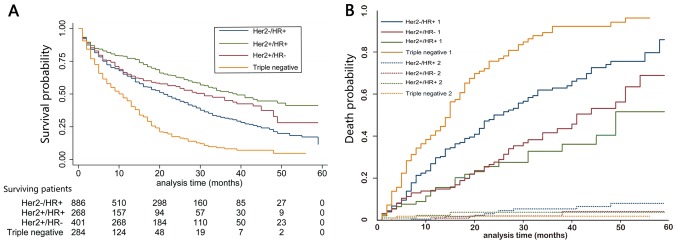

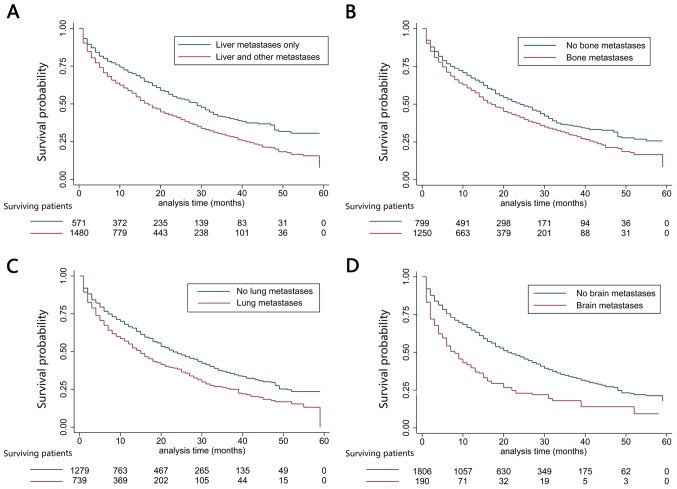

OS analysis

Patients were followed up for 1–59 months, with a median of 12 months; 1,179 cases had succumbed [including 498 with Her2(−)/HR(+), 124 with Her2(+)/HR(−), 155 with Her2(+)/HR(+) and 219 with TNBC]. The median OS of the whole population was 20 months (95% CI, 18.2–21.8 months). In addition, 31.8, 23.1 and 13.9% patients were alive at 3, 4 and 5 years of follow up, respectively (Fig. 2). Differences in OS were statistically significant; TNBC liver metastasis exhibited the most dismal prognosis (median OS was 15 months; 95% CI, 13.4–16.6 months), while, the median OS for Her2(+)/HR(+) BC was 51 months (95% CI, not available; P<0.001; Fig. 3A). Additionally, a plot of the estimated cumulative incidence function for cancer-specific cause of failure was also generated (Fig. 3B). Cases with the only metastatic site in the liver were associated with better prognosis (median OS, 33 months; 95% CI, 24.0–42.0 months) than those with metastases at other sites (median OS, 24 months; 95% CI, 20.2–27.8 months; P<0.001; Fig. 4A). Similarly, patients with bone metastases (median OS, 24.0 months; 95% CI, 19.6–28.4 months) had dismal survival compared with those with no bone metastasis (median OS, 31.0 months; 95% CI, 26.0–36.0 months; P=0.003; Fig. 4B); those with lung metastasis (median OS, 22.0 months; 95% CI, 15.5–28.5 months) had poor survival than those with no lung metastasis (median OS, 30.0 months; 95% CI, 25.5–34.5 months; P=0.001; Fig. 4C); those with brain metastasis (median OS, 4.0 months; 95% CI, 1.2–6.8 months) had poor survival relative to those with no brain metastasis (median OS, 27.0 months; and 95% CI, 23.5–30.5 months; P=0.030; Fig. 4D). However, differences in OS between left (median OS, 26.0 months; 95% CI, 20.0–32.0 months) and right BC (median OS, 27.0 months; 95% CI, was 23.4–30.6 months; P=0.616) was of no statistical significance; negative (median OS, 33.0 months; 95% CI, 24.0–42.0 months) and positive nodes (median OS, 26.0 months; 95% CI, 22.4–29.6 months; P=0.360) was not statistically significant. Furthermore, OS was decreased in older patients (>64 years) (P<0.001), and those of unmarried status (P=0.018), greater tumor size (>50 mm) (P=0.036), advanced stage (P=0.033), without surgery (P=0.009), metastases at other sites (P<0.001), as well as TNBC subtype (P<0.001) (Table II).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival for the entire population.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival based on tumor subtype. (A) P<0.001 upon log-rank test. (B) Estimated cumulative incidence curves for each combination of competing events and tumor subtypes. Solid lines, cancer-specific mortality; broken lines, death due to other reasons. Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival based on different metastatic sites. (A) Patients who have liver metastasis alone vs. those who have metastases in liver as well as other sites, P<0.001 upon log-rank test. (B) Patients who have bone metastasis vs. those with no bone metastasis, P<0.001 upon log-rank test. (C) Patients who have lung metastasis vs. those with no lung metastasis, P<0.001 upon log-rank test. (D) Patients who have brain metastasis vs. those with no brain metastasis, P<0.001 upon log-rank test.

Table II.

Unadjusted OS.

| 95% CI for Hazard ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Median OS (months) | Log-rank P-value | Hazard ratio | Lower | Upper |

| Age | <0.001b | ||||

| <50 | 31 | 1a | |||

| 50–64 | 31 | 1.024 | 0.756 | 1.387 | |

| >64 | 19 | 1.933 | 1.423 | 2.626 | |

| Sex | NA | ||||

| Male | NA | 1a | |||

| Female | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Race | 0.324 | ||||

| Caucasian | 29 | 1a | |||

| African descent | 26 | 1.190 | 0.891 | 1.590 | |

| Others | 24 | 1.280 | 0.815 | 2.011 | |

| Marital | 0.018b | ||||

| Unmarried | 19 | 1a | |||

| Married | 30 | 0.720 | 0.547 | 0.949 | |

| Insurance | 0.310 | ||||

| Uninsured | 10 | 1a | |||

| Insured | 27 | 0.638 | 0.263 | 1.546 | |

| Size (mm) | 0.036b | ||||

| ≤20 | 33 | 1a | |||

| 21–50 | 29 | 1.084 | 0.752 | 1.565 | |

| >50 | 23 | 1.447 | 1.002 | 2.090 | |

| Grade | 0.033b | ||||

| I | 41 | 1a | |||

| II | 34 | 1.525 | 0.698 | 3.330 | |

| III/IV | 23 | 2.019 | 0.950 | 4.292 | |

| Laterality | 0.616 | ||||

| Left | 26 | 1a | |||

| Right | 27 | 1.063 | 0.836 | 1.350 | |

| Nodal stage | 0.360 | ||||

| Node negative | 33 | 1a | |||

| Node positive | 26 | 1.186 | 0.819 | 1.716 | |

| Surgery | 0.009b | ||||

| No | 25 | 1a | |||

| Yes | 31 | 0.728 | 0.571 | 0.927 | |

| Liver metastases only | <0.001b | ||||

| Yes | 33 | 1a | |||

| No | 24 | 1.563 | 1.221 | 2.002 | |

| Bone metastases | 0.003b | ||||

| No | 31 | 1a | |||

| Yes | 24 | 1.433 | 1.127 | 1.823 | |

| Lung metastases | 0.001b | ||||

| No | 30 | 1a | |||

| Yes | 22 | 1.529 | 1.171 | 1.998 | |

| Brain metastases | 0.030b | ||||

| No | 27 | 1a | |||

| Yes | 4 | 1.912 | 1.045 | 3.500 | |

| Subtypes | <0.001b | ||||

| Her2−/HR+ | 24 | 1a | |||

| Her2+/HR− | 49 | 0.477 | 0.315 | 0.721 | |

| Her2+/HR+ | 51 | 0.456 | 0.318 | 0.654 | |

| Triple negative | 15 | 1.931 | 1.455 | 2.563 | |

1, reference value.

P<0.05. CI, confidence interval; Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; NA, not applicable; OS, overall survival.

Prognostic factors and nomogram construction

Multivariate analysis was conducted using the Cox proportional hazard model, which suggested that age at diagnosis, marital status, surgery, bone metastasis, brain metastasis, and tumor subtype were independent risk factors of OS. Nonetheless, gender, nationality, insurance, tumor size, laterality, nodal stage, as well as lung metastasis showed no marked association with OS (Table III). BC-specific mortality among BCLM patients was also presented in Table III. Of note, age at diagnosis (P<0.001), marital status (P=0.042), surgery (P=0.017), bone metastasis (P=0.048), brain metastasis (P=0.002), and tumor subtype (P<0.001) had been identified to be independent prognosis factors.

Table III.

Multivariable Cox regression for all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality among patients with liver metastases.

| All-cause mortality | Cancer-specific mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age | 1.028 (1.018–1.038) | <0.001b | 1.020 (1.010–1.030) | <0.001b |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1a | 1a | ||

| Female | 12,885.534 (0.000–1.253×10131) | 0.949 | 5,933.994 (1,381.922–2.55E+04) | NA |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 1a | 1a | ||

| African descent | 1.076 (0.795–1.458) | 0.635 | 0.936 (0.699–1.250) | 0.660 |

| Others | 1.478 (0.915–2.390) | 0.110 | 1.630 (1.043–2.550) | 0.032b |

| Marital | ||||

| Unmarried | 1a | 1a | ||

| Married | 0.687 (0.512–0.922) | 0.012b | 0.744 (0.559–0.990) | 0.042b |

| Insurance | ||||

| Uninsured | 1a | 1a | ||

| Insured | 0.586 (0.230–1.495) | 0.263 | 0.594 (0.257–1.370) | 0.220 |

| Size (mm) | ||||

| ≤20 | 1a | 1a | ||

| 21–50 | 0.932 (0.636–1.366) | 0.719 | 0.861 (0.603–1.230) | 0.410 |

| >50 | 1.073 (0.722–1.595) | 0.728 | 0.960 (0.654–1.410) | 0.840 |

| Grade | ||||

| I | 1a | 1a | ||

| II | 2.107 (0.951–4.672) | 0.066 | 1.753 (0.793–3.880) | 0.170 |

| III/IV | 2.442 (1.119–5.333) | 0.025b | 2.172 (0.997–4.730) | 0.051 |

| Laterality | ||||

| Left | 1a | 1a | ||

| Right | 1.142 (0.890–1.465) | 0.297 | 0.958 (0.750–1.220) | 0.730 |

| Nodal stage | ||||

| Node negative | 1a | 1a | ||

| Node positive | 1.066 (0.715–1.589) | 0.754 | 1.106 (0.743–1.650) | 0.620 |

| Surgery | ||||

| No | 1a | 1a | ||

| Yes | 0.652 (0.500–0.850) | 0.002b | 0.728 (0.560–0.945) | 0.017b |

| Bone metastases | ||||

| No | 1a | 1a | ||

| Yes | 1.322 (1.027–1.701) | 0.030b | 1.293 (1.003 - 1.670) | 0.048b |

| Lung metastases | ||||

| No | 1a | 1a | ||

| Yes | 1.190 (0.898–1.577) | 0.227 | 1.305 (0.998–1.700) | 0.051 |

| Brain metastases | ||||

| No | 1a | 1a | ||

| Yes | 2.763 (1.467–5.205) | 0.002b | 3.063 (1.493–6.280) | 0.002b |

| Subtypes | ||||

| Her2−/HR+ | 1a | 1a | ||

| Her2+/HR− | 0.474 (0.309–0.725) | 0.001b | 0.429 (0.277–0.665) | <0.001b |

| Her2+/HR+ | 0.420 (0.289–0.610) | <0.001b | 0.527 (0.367–0.755) | <0.001b |

| Triple negative | 2.024 (1.487–2.757) | <0.001b | 2.098 (1.552–2.840) | <0.001b |

1, reference value.

P<0.05. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; NA, not applicable.

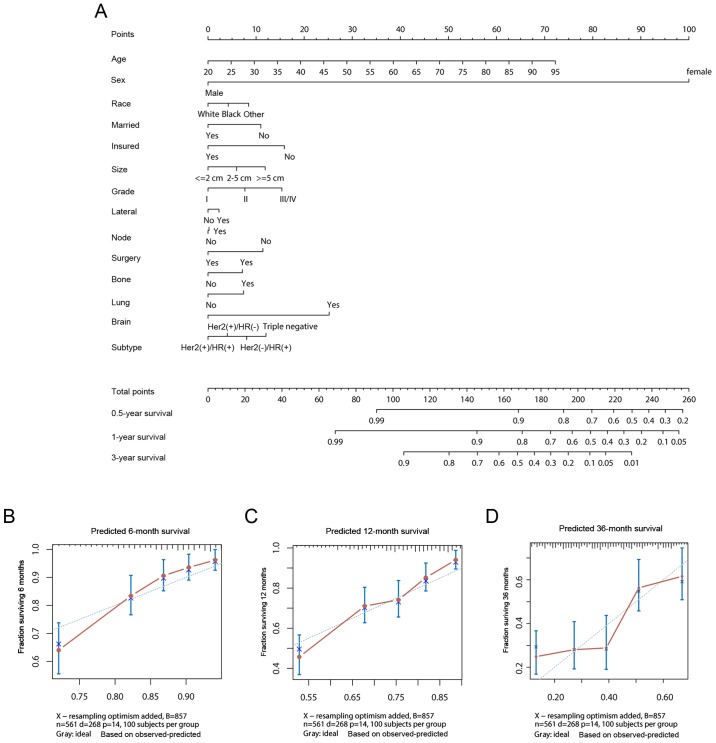

A nomogram for prognosis prediction was constructed using the Cox regression model, which had incorporated the aforementioned independent prognostic factors (Fig. 5A). Specifically, bootstrapping was utilized for model internal validation. The C-index in predicting OS was 0.685 (95% CI, 0.650–0.720); model stability and internal validation had been investigated with 1,000 bootstrap samples. In addition, calibration curves of survival at 6, 12 and 36 months following diagnosis were presented in Fig. 5B-D, respectively. The results predicted by the nomogram corresponded to the actual observations.

Figure 5.

Survival prediction using the nomogram method. (A) Overall survival nomogram for breast cancer liver metastasis. Calibration curves to predict the survival for patients at (B) 6, (C) 12 and (D) 36 months among the study cohort. Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor.

Discussion

The composition of the investigated liver metastasis of the newly diagnosed BC patients was described in the current research; meanwhile, the survival for these cases was also characterized based on tumor subtypes of BC and metastatic sites. Data were generated based on the SEER program, which included ~30% of the US population; thus, our findings may reflect the experience of the real world population. In addition, Fine and Gray's competing risk model based on subdistribution hazards was also recommended to analyze cancer-associated mortality (24). Zhao et al (25) identified the prognostic factors of patients with breast cancer and liver metastasis from 2010 to 2014 using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Of note, there are several advantages in our research. We used Fine and Gray's competing risks model in addition to Cox regression analysis, which to the best our knowledge, has not been reported. We also built a nomogram to predict patient prognosis, which may provide novel information useful to physicians. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to conduct competing risk analysis on BCLM with population-based data. In this context, it is of crucial importance to assess the prognostic factors and outcomes of newly diagnosed patients with BCLM at the population-based level.

According to our results, the median OS was 20 months; 31.8, 23.1 and 13.9% patients were alive at 3, 4, and 5 years after diagnosis, respectively, irrespective of the dismal prognosis for patients with BCLM. However, the prognosis differed greatly among the published articles. For instance, Golse and Adam (7) suggested that BCLM patients receiving surgery were had a median OS of 25–70 months, along with the 5-year survival rate of 20–60%. Wang et al (26) had investigated clinical studies published from 2000 to 2017 concerning transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for BCLM, in which 519 patients were involved, with a median OS for cases receiving TACE of 7.3–47.0 months. Tewes et al (27) had retrospectively analyzed patients with liver-predominant metastatic BC receiving hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, and their results suggested that the median OS was 7 months (range, 1–37 months). Nevertheless, it should be noted that patients were of an advanced stage of disease, with no further systemic treatment available. Moreover, Wang et al (28) had studied the clinical effects of ablation plus TACE on treating BCLM; 50 patients in the TACE group had a median survival time of 11.9 months, while 38 in the combined groups had a markedly longer median survival time of 15.6 months.

Similar to previous studies (17,29,30), our investigation showed that OS differed greatly depending on different subtypes, among which, Her2(+)/HR(+) BC had the most optimal survival (median survival of 51 months). TNBC patients were associated with the worst prognosis (median survival of 15 months). Relative to Her2(−)/HR(+) cases, the risk of death among Her2(+)/HR(+) cases was reduced by 54.4%, while that among TNBC cases was increased by 93.1%. Our data were consistent with prior studies analyzing the effects of tumor subtype on the OS for patients. Similarly, for brain metastasis of BC (19,20), the Her2(+)/HR(+) subtype exhibited the most favorable prognosis, while the TNBC subtype had the worst survival. However, Her2(+)/HR(−) patients had exhibited improved survival than Her2(−)/HR(+) in BCLM; opposing findings were reported for patients with brain metastases.

In addition to tumor subtypes, the metastatic site involved was another crucial factor for survival (7). In accordance with Wang et al (26), our study suggested that, patients who had liver metastasis alone were associated with significantly improved prognosis to those developing metastases in the liver and other sites. Furthermore, the Her2(+)/HR(−) subtype was significantly related to the development of liver metastases alone, which may partly explain for the longer survival times for patients with Her2(+)/ HR(−). Univariate analysis suggested that, lung metastases could negatively affect the OS, but differences in all-cause mortality or the tumor-specific mortality of lung metastasis was not statistically significant upon Cox proportional hazard model analysis. Therefore, further investigation into the influence of lung metastases in BCLM is warranted.

Several limitations should be noted in this study. Firstly, the SEER program collected data regarding disease at initial diagnosis alone, while patients could then develop liver metastasis during their course of disease. Secondly, there may be some bias in treatment, which was not mentioned within the SEER program. Lastly, data regarding the number of metastases, performance status and comorbidities were unavailable from the SEER program.

Regardless of the aforementioned limitations, this study may provide novel insight into the epidemiology of liver metastasis among newly diagnosed BC patients. In addition, the prognostic data regarding tumor subtype, as well as the metastatic sites in the current analysis could provide important clinical knowledge for BCLM cases. Importantly, the efficient nomogram may also permit the assessment of prognosis for every BCLM patient. Nevertheless, clinical studies should be conducted in the future to verify our findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Yue-Ming Du from Wuxi Stomatological Hospital (Wuxi, China) for her continuous support to Dr Qi-Feng Chen in the investigation.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81801804).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

QFC, TH and WL made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the present study. QFC, TH, PW, LJS and ZLH contributed to data analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript revising. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent for participation

We obtained approval from the Ethical Committee and the Institutional Review Board of our University Cancer Center for data analysis and submission of the manuscript.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Bray F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Anderson BO, Jemal A. International variation in female breast cancer incidence and mortality rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1495–1506. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Servick K. Breast cancer. Breast cancer: A world of differences. Science. 2014;343:1452–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.343.6178.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2012. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1044–1052. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893–1907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golse N, Adam R. Liver metastases from breast cancer: What role for surgery? Indications and Results. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soni A, Ren Z, Hameed O, Chanda D, Morgan CJ, Siegal GP, Wei S. Breast cancer subtypes predispose the site of distant metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143:471–478. doi: 10.1309/AJCPYO5FSV3UPEXS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savci-Heijink CD, Halfwerk H, Hooijer GK, Horlings HM, Wesseling J, van de Vijver MJ. Retrospective analysis of metastatic behaviour of breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:547–557. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3352-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Reilly SM, Richards MA, Rubens RD. Liver metastases from breast cancer: The relationship between clinical, biochemical and pathological features and survival. Eur J Cancer. 1990;26:574–577. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(90)90080-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyld L, Gutteridge E, Pinder SE, James JJ, Chan SY, Cheung KL, Robertson JF, Evans AJ. Prognostic factors for patients with hepatic metastases from breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:284–290. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atalay G, Biganzoli L, Renard F, Paridaens R, Cufer T, Coleman R, Calvert AH, Gamucci T, Minisini A, Therasse P, et al. Clinical outcome of breast cancer patients with liver metastases alone in the anthracycline-taxane era: A retrospective analysis of two prospective, randomised metastatic breast cancer trials. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2439–2449. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan XF, Dong NN, Zhang T, Li Q. The prognostic analysis of clinical breast cancer subtypes among patients with liver metastases from breast cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi M, Carioli G, Bonifazi M, Zambelli A, Franchi M, Moja L, Zambon A, Corrao G, La Vecchia C, Zocchetti C, Negri E. Trastuzumab for HER2+ metastatic breast cancer in clinical practice: Cardiotoxicity and overall survival. Eur J Cancer. 2016;52:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toft DJ, Cryns VL. Minireview: Basal-like breast cancer: From molecular profiles to targeted therapies. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:199–211. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, Ibrahim N, Cristofanilli M, Anderson K, Hess KR, Stec J, Ayers M, Wagner P, et al. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5678–5685. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Largillier R, Ferrero JM, Doyen J, Barriere J, Namer M, Mari V, Courdi A, Hannoun-Levi JM, Ettore F, Birtwisle-Peyrottes I, et al. Prognostic factors in 1,038 women with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:2012–2019. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Follana P, Barriere J, Chamorey E, Largillier R, Dadone B, Mari V, Hannoun-Levi JM, Marcy M, Flipo B, Ferrero JM. Prognostic factors in 401 elderly women with metastatic breast cancer. Oncology. 2014;86:143–151. doi: 10.1159/000357781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leone JP, Leone J, Zwenger AO, Iturbe J, Leone BA, Vallejo CT. Prognostic factors and survival according to tumour subtype in women presenting with breast cancer brain metastases at initial diagnosis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;74:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin AM, Cagney DN, Catalano PJ, Warren LE, Bellon JR, Punglia RS, Claus EB, Lee EQ, Wen PY, Haas-Kogan DA, et al. Brain metastases in newly diagnosed breast cancer: A population-based study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leone BA, Vallejo CT, Romero AO, Machiavelli MR, Pérez JE, Leone J, Leone JP. Prognostic impact of metastatic pattern in stage IV breast cancer at initial diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161:537–548. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong Y, Liu YR, Ji P, Hu X, Shao ZM. Impact of molecular subtypes on metastatic breast cancer patients: A SEER population-based study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45411. doi: 10.1038/srep45411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu SG, Li H, Tang LY, Sun JY, Zhang WW, Li FY, Chen YX, He ZY. The effect of distant metastases sites on survival in de novo stage-IV breast cancer: A SEER database analysis. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317705082. doi: 10.1177/1010428317705082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F. Competing risk analysis using R: An easy guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:381–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao HY, Gong Y, Ye FG, Ling H, Hu X. Incidence and prognostic factors of patients with synchronous liver metastases upon initial diagnosis of breast cancer: A population-based study. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:5937–5950. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S178395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang M, Zhang J, Ji S, Shao G, Zhao K, Wang Z, Wu A. Transarterial chemoembolisation for breast cancer with liver metastasis: A systematic review. Breast. 2017;36:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tewes M, Peis MW, Bogner S, Theysohn JM, Reinboldt MP, Schuler M, Welt A. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for extensive liver metastases of breast cancer: Efficacy, safety and prognostic parameters. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:2131–2141. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Liu B, Long H, Zhang F, Wang S, Li F. Clinical study of radiofrequency ablation combined with TACE in the treatment of breast cancer with liver metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:2699–2702. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimbung S, Loman N, Hedenfalk I. Clinical and molecular complexity of breast cancer metastases. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwast AB, Voogd AC, Menke-Pluijmers MB, Linn SC, Sonke GS, Kiemeney LA, Siesling S. Prognostic factors for survival in metastatic breast cancer by hormone receptor status. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:503–511. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2964-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.