Abstract

Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion (DCISM) have worse cancer-specific survival, disease-free survival and overall survival, and a higher mortality rate compared with patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Distinguishing DCISM from DCIS via preoperative imaging could help to predict the prognosis of patients. The present study compared the sonographic and mammographic features of patients with DCIS and DCISM. A total of 147 women (94 patients with DCIS and 53 patients with DCISM) were retrospectively included. The sonographic lesions were classified as either masses or non-mass abnormalities. The lesions observed on mammography were classified as calcifications only, mass, asymmetry or architectural distortion. Statistical comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, Fisher's exact test and multiple logistic regression analysis. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that the presence of calcifications (P=0.038) and vascularity (P=0.025) on sonography were associated with DCISM. Furthermore, a lager distribution of calcifications was associated with a higher likelihood of DCISM (P=0.002). In conclusion, the presence of calcifications and vascularity on sonography or a lager distribution of calcifications on mammography may suggest DCISM.

Keywords: breast ductal carcinoma in situ, microinvasion, sonography, mammography

Introduction

Breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is characterized by a proliferation of malignant epithelial cells confined to the mammary ducts without light-microscopic evidence of invasion through the basement membrane into the surrounding stroma (1). According to the criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), DCIS with a microscopic focus of invasion ≤1 mm in the longest diameter is defined as ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion (DCISM) (2). The proportion of DCIS and DCISM cases detected by screening has markedly increased (3). Recent studies have revealed that DCISM, with its potential for invasion and metastasis, might represent a distinct entity differing from DCIS (4–6). Patients with DCISM had worse cancer-specific survival, disease free survival, and overall survival and a higher mortality rate than patients with DCIS (3,7,8). Distinguishing DCISM from DCIS via preoperative imaging would help to predict the prognosis of patients. Yao et al (6), indicated that DCISM was more likely to have calcifications in the mass and a high degree of vascularization on sonography. However, the study by Yao et al (6) included only DCIS cases that appeared as masses on sonography, and DCIS cases that were non-mass lesions or negative on sonography were excluded. No study has compared the mammographic features of DCIS and DCISM. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to compare the sonographic and mammographic features between patients with DCISM and DCIS.

Patients and methods

Patients

The Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital Ethics Committee approved this retrospective study. The pathologic database of our hospital was searched to identify patients with a pathologic diagnosis of DCIS and DCISM on surgical specimens diagnosed between December 2012 and September 2015. We excluded patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery or who underwent excisional biopsy outside of our hospital. Therefore, 94 DCIS cases and 53 DCISM cases were included. The clinical features, sonographic and mammographic images and pathology records were reviewed.

Clinical features

The clinical features, including clinical presentation and history, were obtained from the medical records. The clinical presentation included observation of a palpable mass, nipple discharge or no symptoms. The clinical history included age, menopausal status, family history of breast cancer and personal history of breast cancer.

Sonography and mammography

Sonographic examinations were performed by one of seven dedicated breast radiologists who specialized in breast ultrasound using an ACUSON S2000 system (Siemens, Germany). The sonographic findings were classified as masses, non-mass abnormalities or no abnormality. A non-mass abnormality was defined as: i) layered duct-like structures without a distinct mass with a zebra pattern or with small nodules less than 3 mm in diameter and ii) ductal dilation (9). When a mass was present, the sonographic findings (shape, orientation, margin, echo pattern and posterior features) were described according to the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon (10). Whether calcifications and vascularity were present in a mass or non-mass were also analyzed.

Bilateral digital mammograms with two standard imaging planes (mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal) were obtained using a digital mammographic unit (Planmed Nuance, Planmed, Helsinki, Finland) in our institution. Because 23 patients in the DCIS group and 14 patients in the DCISM group had mammograms from other hospitals, they did not undergo mammography in our hospital. Therefore, 71 DCIS patients and 39 DCISM patients were included. Mammograms were reviewed for breast composition and lesion characteristics according to the BI-RADS lexicon (10). Based on visual evaluation, the breast composition was classified into the following four categories: i) almost entirely fatty breasts; ii) t scattered areas of fibroglandular density; iii) t heterogeneously dense breasts, and iv) extremely dense breasts. All lesions were classified as either calcifications only, a mass, asymmetry or architectural distortion. The morphology of calcification is divided into three categories: Amorphous, coarse heterogeneous and fine pleomorphic. The distribution of calcification is also divided into three categories: Grouped, regional and segmental.

Ultrasonograms and mammograms were reviewed retrospectively by two breast imaging radiologists who were blinded to the pathologic information but not blinded to the clinical information. When the descriptor differed between the two radiologists, a consensus was reached by discussion.

Histological analysis

All pathologic reports were reviewed. A diagnosis of DCISM was rendered when a microscopic focus of invasion ≤1 mm in the longest diameter within an area of DCIS was present (2). The histopathologic features included the nuclear grade and the presence or absence of comedo-type necrosis. Biological markers including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and the Ki-67 index were examined by immunohistochemical analysis as a routine pathologic assessment in our hospital. ER and PR positivity were defined as nuclear staining in 1% or more of tumor cells. HER2 status was graded as 0, 1+, 2+, and 3+ by immunohistochemistry. HER2 0 and 1+ were considered negative, whereas HER2 3+ was considered positive. Ki-67 expression was quantified using a visual grading system. An estimated percentage of Ki-67 positive cells was determined, and the cutoff for positivity was established at 20% (11).

Statistical analysis

A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the age and maximum diameter of patients with DCISM to those of patients with DCIS. The χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare sonographic and mammographic characteristics, clinicopathologic findings and biomarkers and between the two groups of patients. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in the analysis of sonographic findings that were significant in the univariate analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Data analysis was performed using SPSS v.19.0 statistical software (IBM Corp.).

Results

Clinical and pathologic features

The clinical and pathologic characteristics are summarized in Table I. In addition to the presence of a mass, nipple discharge was more common in patients with DCISM. However, patient age, menopausal status, and family and personal history of breast cancer were not significantly different between the two disease entities (all P>0.05). Patients with DCISM were more likely to have larger and higher grade tumors with comedo-type necrosis, ER negativity, PR negativity, HER2 positivity, and a higher Ki-67 index than patients with DCIS (all P<0.05).

Table I.

Clinical-pathologic parameters in patients with DCIS (n=94) and DCISM (n=53).

| Clinical-pathologic parameters | DCIS, n=94 (%) | DCISM, n=53 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48±11a | 46±8a | 0.267 |

| Menopausal status | 0.728 | ||

| Premenopausal | 63 (67.0) | 37(69.8) | |

| Postmenopausal | 31 (33.0) | 16(30.2) | |

| Clinical presentation | 0.015 | ||

| Mass | 58 (61.7) | 38 (71.7) | |

| Nipple discharge | 16 (17.0) | 13(24.5) | |

| Asymptomatic | 20 (21.3) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Family history of breast cancer | 0.509 | ||

| Yes | 2 (2.1) | 3 (5.7) | |

| No | 92 (97.9) | 50 (94.3) | |

| Personal history of breast cancer | 0.480 | ||

| Yes | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 91 (96.8) | 53 (100.0) | |

| Maximum diameter (cm)a | 2.1±1.5a | 3.4±1.5a | <0.001 |

| Nuclear grade | <0.001 | ||

| Low or intermediate | 68 (72.3) | 11 (20.8) | |

| High | 26 (27.7) | 42 (79.2) | |

| Comedo-type necrosis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3 (3.2) | 17 (32.1) | |

| No | 91 (96.8) | 36 (67.9) | |

| Estrogen receptor | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 86 (91.5) | 31 (58.5) | |

| Negative | 8 (8.5) | 22 (41.5) | |

| Progesterone receptor | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 76 (80.9) | 16 (30.2) | |

| Negative | 18 (19.1) | 37 (69.8) | |

| HER2 status | 0.001 | ||

| 0, 1+ | 46 (48.9) | 11 (20.8) | |

| 3+ | 16 (17.1) | 21 (39.6) | |

| 2+ | 32 (34.0) | 21 (39.6) | |

| Ki-67 index (%) | 0.006 | ||

| >20 | 28 (29.8) | 28 (52.8) | |

| ≤20 | 66 (70.2) | 25 (47.2) |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; DCISM, ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Sonographic features

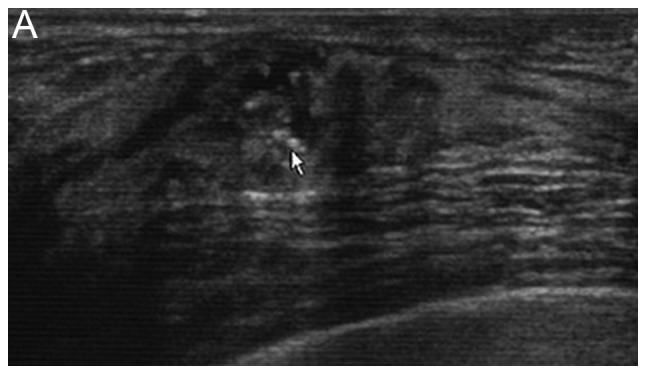

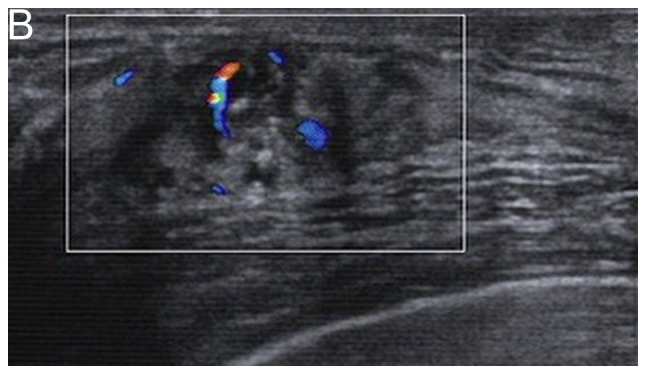

No abnormal signs were found in 11 patients from the DCIS group. Thus, 83 mass or non-mass abnormalities were included in the DCIS group. Univariate analysis of sonographic features indicated that non circumscribed margins, the presence of vascularity and calcification (Fig. 1) were significantly more common in DCISM cases (Table II). Multivariate analysis showed that the presence of vascularity and calcification were independent variables associated with DCISM (Table III).

Figure 1.

A 43-year-old premenopausal woman presented with a palpable right breast mass and a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. (A) A grayscale sonogram demonstrates a hypoechoic echo non-mass abnormality. Punctate echogenic foci within the lesion represent associated calcifications (arrow). (B) A color Doppler sonogram shows the presence of vascularity.

Table II.

Univariate analysis of sonographic features in DCIS and DCISM.

| Sonographic features | DCIS, n=83 (%) | DCISM, n=53 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass | 47 (56.6) | 25 (47.2) | 0.281 |

| Shape | 0.158 | ||

| Oval | 9 (19.1) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Irregular | 38 (80.9) | 24 (96.0) | |

| Orientation | 0.364 | ||

| Parallel | 38 (80.9) | 23 (92.0) | |

| Not parallel | 9 (19.1) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Margin | 0.015 | ||

| Circumscribed | 12 (25.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not circumscribed | 35 (74.5) | 25 (100.0) | |

| Echo pattern | 0.502 | ||

| Hypoechoic | 44 (93.6) | 25 (100.0) | |

| Complex cystic and solid | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Posterior features | 0.999 | ||

| No posterior features or enhancement | 42 (89.4) | 23 (92.0) | |

| Shadowing or combined pattern | 5 (10.6) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Non-mass abnormality | 36 (43.4) | 28 (52.8) | 0.381 |

| Layered duct-like structures without a distinct mass with a zebra pattern or with small nodules less than 3 mm in diameter | 28 (77.8) | 25 (89.3) | |

| Ductal dilation | 8 (22.2) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Vascularity | 0.002 | ||

| Absent | 37 (44.6) | 10 (18.9) | |

| Present | 46 (55.4) | 43 (81.1) | |

| Calcification | 0.003 | ||

| Absent | 56 (67.5) | 22 (41.5) | |

| Present | 27 (32.5) | 31 (58.5) |

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; DCISM, ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion.

Table III.

Multivariate analysis of sonographic features in ductal carcinoma in situ and ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion.

| Sonographic features | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Vascularity | 0.025 | |

| Absent | Reference | |

| Present | 2.660 (1.132–6.251) | |

| Calcification | 0.038 | |

| Absent | Reference | |

| Present | 2.220 (1.044–4.723) |

OR, odds ratio.

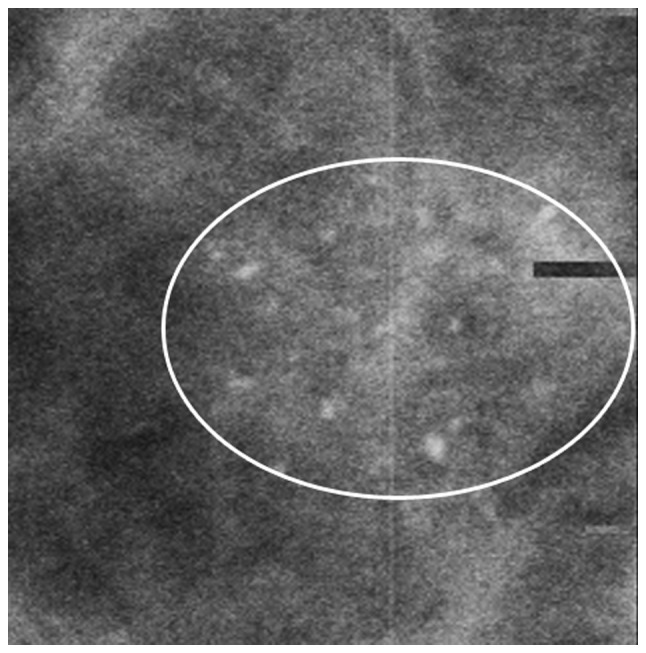

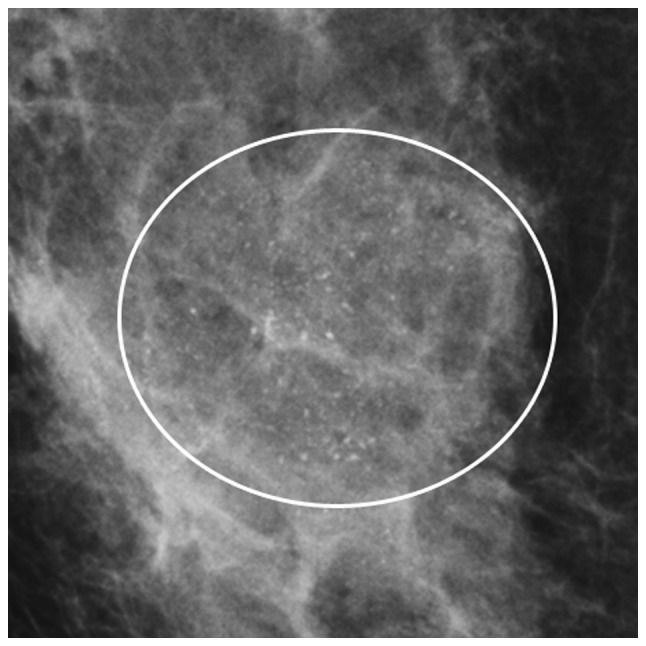

Mammographic features

No abnormal signs on mammography were found in 21 patients in the DCIS group and 3 patients in the DCISM group. Among 24 cases, the classification of the breast composition was as follows: 7 cases were extremely dense, 16 cases were heterogeneously dense, and 1 case displayed scattered areas of fibroglandular density. Therefore, 50 abnormalities in the DCIS group and 36 abnormalities in the DCISM group were included. Larger distribution of calcifications was associated with DCISM (Table IV; Figs. 2 and 3).

Table IV.

Mammographic features in DCIS and DCISM.

| Mammographic feature | DCIS, n=50 (%) | DCISM, n=36 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcifications | 37 (74.0) | 23 (63.9) | 0.195 |

| Morphology | 0.130 | ||

| Amorphous | 19 (51.4) | 6 (26.1) | |

| Coarse heterogeneous | 2 (5.4) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Fine pleomorphic | 16 (43.2) | 16 (69.6) | |

| Distribution | 0.002 | ||

| Grouped | 25 (67.6) | 5 (21.8) | |

| Regional | 8 (21.6) | 11 (47.8) | |

| Segmental | 4 (10.8) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Massa | 4 (8.0) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Focal asymmetryb | 6 (12.0) | 6 (16.7) | |

| Architectural distortionc | 3 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Masses were irregular, high density with indistinct margin. DCIS group, mass with calcification in 2 cases; DCISM group, mass with calcification in 2 cases.

DCIS group, focal asymmetry with calcification in 2 cases; DCISM group, focal asymmetry with calcification in 2 cases.

DCIS group, architectural distortion with calcification in 3 cases. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; DCISM, ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion.

Figure 2.

A 59-year-old postmenopausal woman exhibited amorphous calcifications with grouped distribution on mammography of the right breast (circle) and a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ.

Figure 3.

A 61-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with a palpable right breast mass and a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. A mammogram shows fine pleomorphic calcifications with regional distribution (circle).

Discussion

A palpable mass was the main symptom of DCIS and DCISM lesions (5,12). In addition, nipple discharge was commonly encountered in DCISM. Factors including age, menopausal status, and family and personal history of breast cancer were not found to be associated with the presence of microinvasion, which was consistent with a study by Ozkan-Gurdal et al (13). Pathologically, DCISM tended to be larger and have a higher nuclear grade, comedo-type necrosis, ER negativity, PR negativity, HER2 positivity and a higher Ki-67 index than DCIS, which was similar to the results of previous studies (6,12–14).

Only one study performed a detailed comparison of the sonographic features of DCIS and DCISM (6). However, Yao et al (6) investigated only lesions observed as masses on sonography. Previous studies have shown that the sonographic findings of DCIS could include a mass, a non-mass or no abnormal findings and approximately 49 to 60% of DCIS cases appear as non-mass abnormalities on sonography (15,16). According to previous studies, we classified the sonographic findings of DCIS and DCISM as masses, non-mass lesions or no abnormality. The proportion of non-mass lesions was greater in the DCISM group than in the DCIS group (52.8% vs. 43.4%), but the difference was not significant. Yao et al (6), reported that DCISM was more likely to have calcifications and a high degree of vascularization than DCIS. In our study, univariate and multivariate analyses also showed that the presence of calcifications and vascularity were variables associated with DCISM. Calcifications are associated with a high nuclear grade and necrosis (6,17,18). The pathogenesis of DCISM may be related to the rapid growth and active metabolism of tumors, in which oxygen and nutrition are insufficient, leading to the development of local ischemic necrosis and calcium salt deposition, which is detected as calcifications (6). Although sonography is less sensitive than mammography for the identification of calcifications (18), the ability to visualize calcifications on sonography has been described (16,19). In a study using mammography as the gold standard, Yang (19) reported that ultrasound achieved a sensitivity of 95%, a specificity of 87.8% and an accuracy of 91% for the detection of calcification. Other studies have reported that calcifications of DCIS were demonstrated on sonography in 54.1 to 74% of DCIS lesions (15,17). In our study, no sonographic abnormalities were found in 11 patients in the DCIS group. However, calcifications were found on mammography. Identifying isolated calcifications within normal breast tissue, that consists of increased hyperechoic and heterogeneous fibrous tissue, is thought to be more difficult using sonography. This is primarily due to the lack of contrast between the normal parenchyma with hyperechoic heterogeneous fibrous structures and calcifications (20). Angiogenesis is the formation of new capillaries from the existing vascular network and is essential for tumor growth and dissemination (21). Cao et al (22), established that the comedo-type and high nuclear grade DCIS, which has a high potential for invasive transformation, are significantly associated with high microvessel counts. In our study, a significant correlation was observed between high grade tumors, comedo-type necrosis and DCISM. Thus, the presence of vascularity on sonography is associated with DCISM.

Mammography is widely accepted as the most important imaging method for the detection of DCIS. DCIS manifests as calcifications in 62–98% of cases (23–25). In our study, calcifications were found more commonly in DCIS than in DCISM (74% vs. 63.9%), but the difference was not significant. The distribution of calcifications was mainly regional and segmental in DCISM cases and mainly grouped and regional in DCIS cases, resulting in a statistically significant difference between the two groups (P<0.05). Similar results regarding the association between a higher cluster area of the calcifications and an increased likelihood of invasion were reported by Lagios et al (25). Regarding the 24 lesions that were not visible on mammography, 10 lesions manifested as masses and 14 manifested as non-mass abnormalities on sonography. Dense breasts composed 95.8% (23/24) of the cases. Mammographic sensitivity is significantly inversely related to breast density and decreases from 100% in fatty breasts to 45–48% in extremely dense breasts (26,27). Our findings suggested that sonography may be more effective than mammography for the detection of DCIS in patients with dense breasts or lesions without calcification.

There are a few limitations in the present study. First, it was a retrospective study. Additionally, several patients who had mammograms performed at other hospitals did not undergo mammography in our hospital. Therefore, we did not match the mammography and sonography results for lesions. Second, we did not consider the distribution and degree of vascularization, and three color Doppler indices (peak systolic velocity, pulsatility index, and resistive index), elastography on sonography and circulating tumor cell were not used for comparisons (6). The reasons were as follows (1), Because of the small sample size, it was difficult to classify the distribution and degree of vascularization (2). Color Doppler indices, elastography on sonography and circulating tumor cell were not routinely used during the study period. Third, other methods of diagnostics, for example a thermography device, are not available at our institute.

In summary, imaging features including the presence of calcifications and vascularity on sonography and a larger area of calcifications on mammography were associated with DCISM. Even so, pathological analysis is still the gold standard. Additional larger prospective studies are needed for further research.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DCISM

ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- BI-RADS

breast imaging reporting and data system

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PR

progesterone receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81372817).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

HLW made substantial contributions to the study design, and the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. JJL, JGL and CT participated in the design of the study and the analysis of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. YPY helped conduct the statistical analysis. RG, XFJ, FTL and YH participated in data acquisition and manuscript revision. FXS contributed to the study design and was involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital. Written informed consent was not required for the review of these images and data.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Schnitt SJ, Silen W, Sadowsky NL, Connolly JL, Harris JR. Ductal carcinoma in situ (intraductal carcinoma) of the breast. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:898–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, Bassett LW, Berry D, Bland KI, Borgen PI, Clark G, Edge SB, Hayes DF, et al. Revision of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3628–3636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W, Zhu W, Du F, Luo Y, Xu B. The demographic features, clinicopathological characteristics and cancer-specific outcomes for patients with microinvasive breast cancer: A SEER database analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42045. doi: 10.1038/srep42045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okumura Y, Yamamoto Y, Zhang Z, Toyama T, Kawasoe T, Ibusuki M, Honda Y, Iyama K, Yamashita H, Iwase H. Identification of biomarkers in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast with microinvasion. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:287. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira CC, Mercado CL, Cangiarella JF, Moy L, Toth HK, Guth AA. Microinvasive ductal carcinoma in situ: Clinical presentation, imaging features, pathologic findings, and outcome. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao JJ, Zhan WW, Chen M, Zhang XX, Zhu Y, Fei XC, Chen XS. Sonographic features of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast with microinvasion: Correlation with clinicopathologic findings and biomarkers. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1761–1768. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.14.07059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sopik V, Sun P, Narod SA. Impact of microinvasion on breast cancer mortality in women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang Y, Wu J, Wang W, Fei X, Zong Y, Chen X, Huang O, He J, Chen W, Li Y, et al. Biologic behavior and long-term outcomes of breast ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64182–64190. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gwak YJ, Kim HJ, Kwak JY, Lee SK, Shin KM, Lee HJ, Kim GC, Jang YJ, Han MH, Park JY, Jung JH. Ultrasonographic detection and characterization of asymptomatic ductal carcinoma in situ with histopathologic correlation. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:364–371. doi: 10.1258/ar.2011.100391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.5th. American College of Radiology; Reston, VA: 2013. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penault-Llorca F, André F, Sagan C, Lacroix-Triki M, Denoux Y, Verriele V, Jacquemier J, Baranzelli MC, Bibeau F, Antoine M, et al. Ki67 expression and docetaxel efficacy in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2809–2815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Gao EL, Zhou YL, Zhai Q, Zou ZY, Guo GL, Chen GR, Zheng HM, Huang GL, Zhang XH. Different distribution of breast ductal carcinoma in situ, ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion, and invasion breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:262. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozkan-Gurdal S, Cabioglu N, Ozcinar B, Muslumanoglu M, Ozmen V, Kecer M, Yavuz E, Igci A. Factors predicting microinvasion in Ductal Carcinoma in situ. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:55–60. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sue GR, Lannin DR, Killelea B, Chagpar AB. Predictors of microinvasion and its prognostic role in ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg. 2013;206:478–481. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee MH, Ko EY, Han BK, Shin JH, Ko ES, Hahn SY. Sonographic findings of pure ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Ultrasound. 2013;41:465–471. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe T, Yamaguchi T, Tsunoda H, Kaoku S, Tohno E, Yasuda H, Ban K, Hirokaga K, Tanaka K, Umemoto T, et al. Ultrasound image classification of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast: Analysis of 705 DCIS lesions. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:918–925. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagashima T, Hashimoto H, Oshida K, Nakano S, Tanabe N, Nikaido T, Koda K, Miyazaki M. Ultrasound demonstration of mammographically detected microcalcifications in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer. 2005;12:216–220. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.12.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rauch GM, Kuerer HM, Scoggins ME, Fox PS, Benveniste AP, Park YM, Lari SA, Hobbs BP, Adrada BE, Krishnamurthy S, Yang WT. Clinicopathologic, mammographic, and sonographic features in 1187 patients with pure ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast by estrogen receptor status. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:639–647. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2598-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang WT, Suen M, Ahuja A, Metreweli C. In vivo demonstration of microcalcification in breast cancer using high resolution ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:685–690. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.835.9245879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gufler H, Buitrago-Téllez CH, Madjar H, Allmann KH, Uhl M, Rohr-Reyes A. Ultrasound demonstration of mammographically detected microcalcifications. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:217–221. doi: 10.1080/028418500127345370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman J. What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao Y, Paner GP, Kahn LB, Rajan PB. Noninvasive carcinoma of the breast: Angiogenesis and cell proliferation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:893–896. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-893-NCOTBA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dershaw DD, Abramson A, Kinne DW. Ductal carcinoma in situ: Mammographic findings and clinical implications. Radiology. 1989;170:411–415. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.2.2536185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stomper PC, Connolly JL, Meyer JE, Harris JR. Clinically occult ductal carcinoma in situ detected with mammography: Analysis of 100 cases with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1989;172:235–241. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.1.2544922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagios MD, Westdahl PR, Margolin FR, Rose MR. Duct carcinoma in situ. Relationship of extent of noninvasive disease to the frequency of occult invasion, multicentricity, lymph node metastases, and short-term treatment failures. Cancer. 1982;50:1309–1314. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821001)50:7<1309::AID-CNCR2820500716>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg WA, Gutierrez L, NessAiver MS, Carter WB, Bhargavan M, Lewis RS, Ioffe OB. Diagnostic accuracy of mammography, clinical examination, US, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. Radiology. 2004;233:830–849. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: An analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165–175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.