Abstract

Introduction

Longer durations of cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross clamp are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Little is known about the effect of automated knot fasteners (Cor-Knot®) in minimally invasive mitral valve repair on operative times and outcomes. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether these devices shortened cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross clamp times and whether this impacted on postoperative outcomes.

Materials and methods

All patients undergoing isolated minimally invasive mitral valve repair by a single surgeon between March 2011 and March 2016 were included (n = 108). Two cohorts were created based on the use (n = 52) or non-use (n = 56) of an automated knot fastener. Data concerning intraoperative variables and postoperative outcomes were collected and compared.

Results

Preoperative demographics were well matched between groups with no significant difference in logistic Euroscore (manual vs automated: median 3.1, interquartile range, IQR, 2.1–5.5, vs 5.4, IQR 2.2–8.3; P = 0.07, respectively). Comparing manually tied knots to an automated fastener, cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross clamp times were significantly shorter in the automated group (cardiopulmonary bypass: median 200 minutes, IQR 180–227, vs 165 minutes (IQR 145–189 minutes), P < 0.001; aortic cross clamp 134 minutes (IQR 121–150 minutes) vs 111 minutes (IQR 91–137 minutes), P < 0.001, respectively). There was no mortality and no strokes, nor were there any differences in postoperative outcomes including reoperation for bleeding, renal failure, intensive care or hospital stay.

Conclusions

The use of an automated knot fastener significantly reduces cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross clamp times in minimally invasive mitral valve repair but this does not translate into an improved clinical outcome.

Keywords: Minimally invasive, Mitral valve repair, Operative times, Automated knot fastener, Cor-Knot

Introduction

Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery has become the standard of care at certain specialised centres worldwide due to reports of excellent results. The belief that this procedure results in less surgical trauma, blood loss, transfusion and pain, which translates into a reduced hospital stay, faster return to normal activities and less use of rehabilitation resources has driven this development by both surgeons and patients alike. Almost all the data on this procedure have reported longer operative times and the learning curve is lengthy (75–125 cases), which has unfortunately deterred many surgeons from adopting this procedure.1

Standard surgical instruments will not fit through the 4–6 cm mini-thoracotomy, necessitating the use of modified shafted instrumentation. Tying secure knots remotely with a 29-cm shafted knot pusher requires careful coordination with the surgical assistant, who may be inexperienced. It may be time consuming, with an increased incidence of loose or ‘air knots’ compared with tying by hand. Correction of ‘air knots’, particularly during supra-annular placement of a prosthetic valve, is time consuming and challenging.

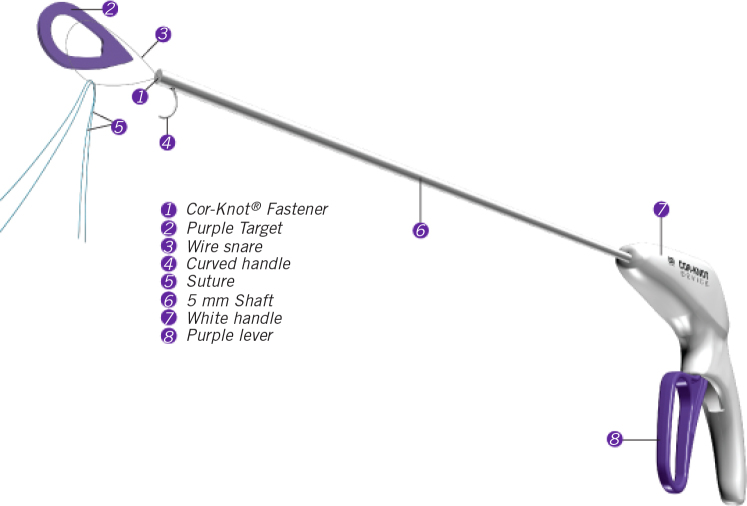

The use of an automated knot fastener (Cor-Knot® Device, LSI Solutions, Victor, NY; fig 1) potentially overcomes these problems and may shorten operative times, but it carries a financial implication. It is known that increased operative times, such as cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and aortic cross-clamp (AXC) time lead to a higher risk of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and adverse outcomes.2 Thus, any intervention which may shorten operative times may also enhance patient safety and improve clinical outcomes.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Corknot® device (image courtesy of LSI solutions, all rights reserved).

Automated knot fasteners have been tested in an ex-vivo model where mitral annuloplasty ring sutures secured with the Cor-Knot device were stronger, more consistent and faster than with manually tied knots.3 In a small study of minimally invasive mitral valve repair, Grapow et al reported encouraging results with shorter operative times.4 The aim of our retrospective study was to evaluate the effect of the introduction of an automated knot fastener for annuloplasty suture attachment on CPB and AXC times, as well as postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing minimally invasive mitral valve repair.

Materials and methods

All patients undergoing isolated minimally invasive mitral valve repair by a single surgeon over a five-year period between March 2011 and March 2016 were included. Those undergoing minimally invasive valve replacement and/or concomitant procedures were excluded to minimise confounding variables. Details of the operative technique have been previously published.5 In brief, a 4–6 cm right mini-thoracotomy using femoral/internal jugular vacuum-assisted CPB was used with systemic hypothermia to 28–32 degrees C and antegrade/retrograde cold blood cardioplegia every 20–30 minutes. Mitral repair techniques included annuloplasty in all cases, with either the loop technique or standard Carpenterian resection (triangular or quadrangular resection).

We retrospectively collected data concerning preoperative and intraoperative variables and postoperative outcomes. Follow-up echocardiograph results were also reviewed. Patients were divided into two cohorts according to whether the annuloplasty sutures were tied manually or by using an automated knot fastener (Cor-Knot). We then compared intra- and postoperative variables between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

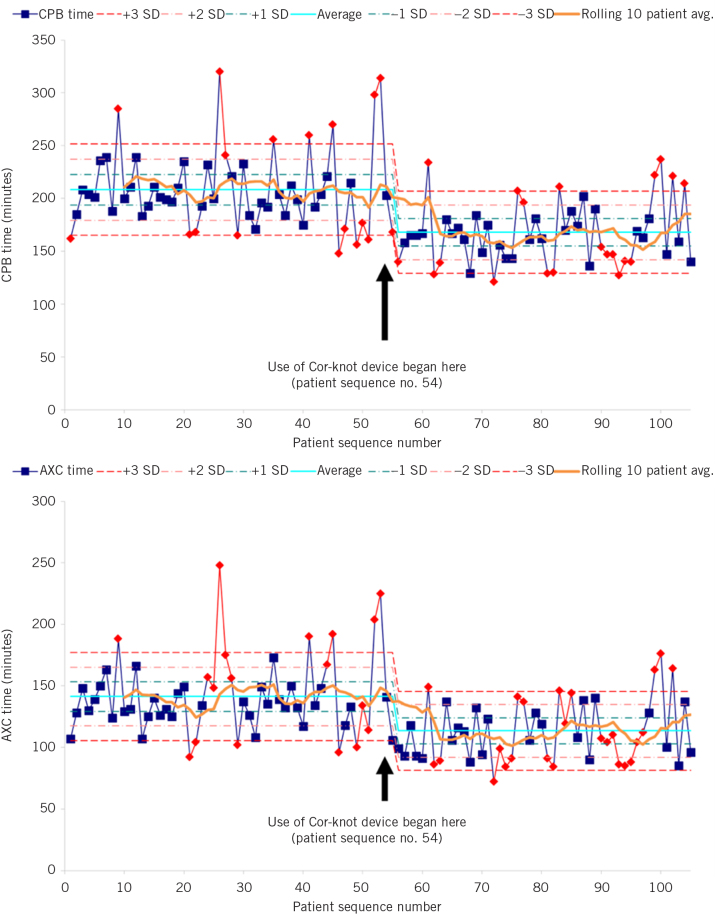

Skewed continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are shown as percentages. Univariate comparisons were made with Wilcoxon rank sum tests and t-tests as appropriate. In all cases a P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, Version 9.3. CBP and AXC times for single cases were analysed and plotted using a statistical process control chart. Data for the first ten patients were used to plot a reference mean time (represented by the cyan line in fig 2). For easier interpretation, a smoothing line calculated by taking the rolling 10-patient mean is included and represented by the orange line in the statistical process control chart. Single-patient data are then plotted against this mean (± 1 standard deviation, ± 2 standard deviations and ± 3 standard deviations). Single-patient data points are represented in blue when the process is ‘in control’ or in red when the process is ‘out of control’.6 Where five or more observations in a row fell outside the original mean plus or minus two standard deviations, a reset of the reference mean was triggered. We also compared the first ten patients in the series with the first ten patients that underwent surgery following the introduction of the Cor-Knot device.

Figure 2.

Statistical process control charts showing cardiopulmonary bypass time and aortic cross clamp time in consecutive minimally invasive mitral valve repair patients (AXC, aortic cross clamp; SD, standard deviation).

Results

During the analysed period, 108 patients underwent isolated minimally invasive mitral valve repair by a single surgeon. A total of 56 cases were performed using manually tied knots and 52 were performed using the Cor-Knot device. The Cor-Knot device was introduced at procedure number 54; three further cases were performed without Cor-Knot after its introduction, while the additional cost was rationalised, and following this, all procedures were performed using the device.

The preoperative characteristics of the two groups were comparable (Table 1). Of the 19 variables analysed, only one was significantly different between the two groups: there were five patients with diabetes in the manually tied knots group, while there were none in the Cor-Knot group (P = 0.023). There was no significant difference in median logistic EuroSCORE between groups (Cor-Knot vs manually tied: 5.4, IQR 2.2–8.3, vs 3.1, IQR 2.1–5.5, P = 0.07, respectively).

Table 1.

Patient and operative characteristics.

| Characteristic | No Cor-Knot used | Cor-Knot used | P-value |

| Patients (n) | 56 | 52 | |

| Age at operation (years) | 61 (56, 69) | 60 (49, 70) | 0.38 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.0 (24.5, 28.7) | 25.9 (23.0, 28.7) | 0.35 |

| Female | 17 (30) | 8 (15) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | 0.023 |

| Hypertension | 17 (30) | 14 (27) | 0.69 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 12 (21) | 12 (23) | 0.84 |

| Unstable angina | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| New York Heart Association score ≥ III | 16 (29) | 9 (17) | 0.17 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction: | |||

| 30–49% | 3 (5) | 7 (13) | 0.19 |

| < 30% | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | > 0.99 |

| Myocardial infarction within 90 days of surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Current smoker | 6 (11) | 2 (4) | 0.27 |

| History of stroke | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.61 |

| History of respiratory disease | 4 (7) | 5 (10) | 0.74 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 0.62 |

| History of renal disease | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 0.36 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 3.1 (2.1, 5.5) | 5.4 (2.2, 8.3) | 0.07 |

| Non-elective | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 0.11 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (minutes) | 200 (180, 227) | 165 (145, 189) | < 0.001 |

| Aortic cross clamp time (minutes) | 134 (121, 150) | 111 (91, 137) | < 0.001 |

| Valve pathology: | |||

| Degenerative, fibroelastic deficiency or forme fruste | 46 (82) | 50 (96) | 0.02 |

| Functional | 6 (11) | 1 (2) | 0.11 |

| Infection/paraprosthetic leak | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | > 0.99 |

| Congenital | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | > 0.99 |

| Senile | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | > 0.99 |

| Active infection | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0.48 |

| Previous infection | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | > 0.99 |

| Valve size (mm) | 32.7 ± 2.5 | 32.9 ± 3.0 | 0.73 |

Median CBP and AXC times were significantly shorter in the Cor-Knot group (CPB: 200 minutes (IQR 180–227 minutes) vs 165 minutes (IQR 145–189 minutes), P < 0.001; AXC: 134 minutes (IQR 121–150 minutes) vs 111 minutes (IQR 91–137 minutes), P < 0.001). Statistical process control chart analysis showed a significant reduction in CPB time and AXC time at patient number 56, where a change in the reference mean was triggered (fig 2).

There was no mortality and no strokes in either group. No differences were detected in terms of other postoperative outcomes: reoperation for bleeding, acute kidney injury, intubation time, intensive care admission and hospital stay were comparable between the groups (Table 2). A total of 103/108 patients (95%) were discharged with 0+ mitral regurgitation, 4/108 (4%) with 1+, 1/108 (1%) with 2+. At three years of follow-up, one patient in each group had developed greater than 2+ mitral regurgitation.

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes.

| Outcome | No Cor-Knot used | Cor-Knot used | P-value |

| Patients (n) | 56 | 52 | |

| In-hospital mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| CVA or TIA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Reoperation for bleeding | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 0.43 |

| Acute renal failure | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation | 9 (16) | 5 (10) | 0.32 |

| Intubation time (hours) | 8 (5.5, 10) | 7 (5, 10) | 0.44 |

| Intubated > 48 hours | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| ICU stay (days) | 3 (2, 4) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.29 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 6 (5, 8) | 6 (5, 7) | 0.72 |

CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ICU, intensive care unit; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

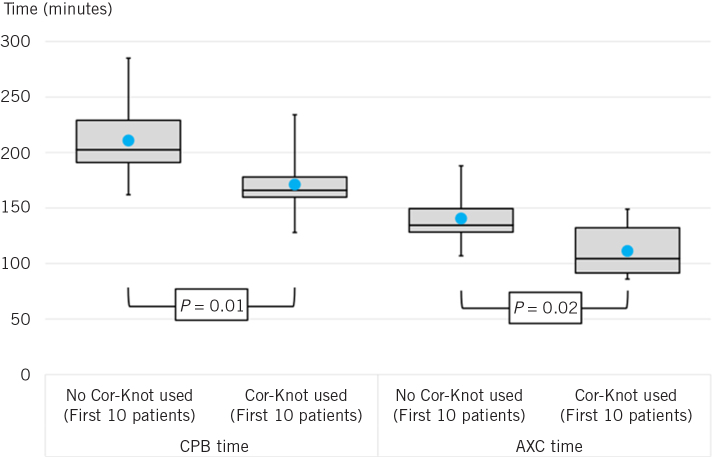

We compared CPB and AXC time between the first ten patients included in this study and the first ten patients that underwent surgery following the introduction of the Cor-knot device: both CPB and AXC time were shorter following the introduction of the Cor-knot device (P = 0.01 and 0.02, respectively; fig 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross clamp time between the first 10 patients included in the study and the first 10 patients that underwent surgery following the introduction of the Cor-Knot device.

Discussion

Our aim was to assess the effect of the introduction of an automated knot fastener (Cor-Knot) on operative times during minimally invasive mitral valve repair and whether any temporal efficiency savings translated into improved clinical outcomes. Median CPB and AXC times were 35 minutes and 23 minutes shorter, respectively, in the Cor-Knot group but this did not lead to any difference in postoperative outcomes. Our data are consistent with those reported by Grapow et al in a smaller study, who showed a 14-minute reduction in both CPB and AXC times,4 and with that from Lee et al in an ex-vivo mitral valve annuloplasty porcine model who showed a saving of one minute per knot in the Cor-Knot group compared with hand tying.3 Chitwood’s group has also presented data reporting savings of 15 minutes and 28 minutes in CPB and AXC times during robotic mitral valve repair when comparing Cor-Knot with robotic tying.

A consistent finding in almost all the published literature of mitral valve repair through a right mini-thoracotomy is of increased operative times compared with sternotomy, particularly at the start of the learning curve. Two meta-analyses comparing minimally invasive to sternotomy mitral valve surgery showed that CPB times were 33 and 26 minutes longer in the minimally invasive group, and 21 minutes longer in the AXC group.7,8 Thus, the time saving from the introduction of an automated knot fastener effectively balances out the increase in operative times with minimally invasive mitral valve repair and will undoubtedly aid surgeons making the transition from a sternotomy approach to a right mini-thoracotomy approach.

There are very few operative interventions that have led to such significant time savings. Saving time during the first CPB run is advantageous as it provides more flexibility to the surgeon in case the repair needs modifying during a second or even third period of aortic clamping. Increased CPB and AXC times are independent predictors of morbidity and mortality in cardiac surgery.9 However, despite this association, we demonstrated that there was no significant difference in postoperative outcome. This is likely because the time differences were not of a sufficient magnitude to affect clinical outcomes, as our strategy of antegrade and retrograde cardioplegia combined with systemic hypothermia probably ensured good myocardial protection.

One constraint of minimally invasive surgery is the need for remote knot tying, which is typically accomplished with the use of a knot pusher. This method may be time consuming, with large variation depending upon surgeon experience. The Cor-Knot technology was developed to address this unmet need in the field of minimally invasive valve surgery. It was designed to enable quick, reliable and easy suture fastening in a minimally invasive setting. With a single squeeze of the lever, the device remotely and automatically secures 2-0 suture with a titanium fastener, while also simultaneously trimming excess suture tails (fig 1). Lee et al have shown that the suture attachment produced by the Cor-knot device is stronger and more consistent with less variability in attachment pressure than manually tied knots.3 When tying knots remotely with a knot pusher, undesirable loose or ‘air’ knots can occur when the coordination between surgeon and assistant is suboptimal, particularly when the assistant is inexperienced. This is effectively eliminated by an automated fastener and is most valuable during supra-annular placement of a valve prosthesis, when correcting a loose knot can be time consuming.

Our study has a few limitations. First, it is a retrospective cohort study with treatment allocation on a temporal basis. We have minimised potential confounders of operative time by only including a single surgeon’s data of patients undergoing identical procedures (minimally invasive mitral valve repair), excluding patients who had concomitant procedures. An unavoidable confounding factor is the learning curve on operative times but this is unlikely to have played a major part in our study as the reduction in operative times was not a gradual improvement but rather a ‘step change’ coinciding with the introduction of the Cor-Knot device. So far only one paper has been published specifically looking at the role of the learning curve in minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. Holzhey et al analysed a total of 3895 mitral valve procedures performed by 17 different surgeons and showed that the learning curve of minimally invasive mitral valve repair does not reduce operative times but instead leads to a significant reduction in adverse events.1 The authors specifically found that AXC time and total operating time were quite stable from the beginning of each surgeon’s experience. Despite the above points, it is possible that a learning curve effect contributed to the reduction in AXC and CPB time we recorded in our study.

Conclusions

To conclude, the use of an automated knot fastener (Cor-Knot) instead of hand-tied knots for annuloplasty suture attachment significantly reduces cardiopulmonary bypass and cross clamp times in minimally invasive mitral valve repair, but this does not translate into improved post-operative clinical outcomes.

References

- 1.Holzhey DM, Seeburger J, Misfeld M et al. Learning minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: A cumulative sum sequential probability analysis of 3895 operations from a single high-volume center. Circulation 2013; : 483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sablotzki A, Friedrich I, Mühling J et al. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome following cardiac surgery: different expression of proinflammatory cytokines and procalcitonin in patients with and without multiorgan dysfunctions. Perfusion 2002; : 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CY, Sauer JS, Gorea HR et al. Comparison of strength, consistency, and speed of COR-KNOT versus manually hand-timed knots in an ex vivo minimally invasive model. Innovations (Phila) 2014; : 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grapow MTR, Mytsyk M, Fassl J et al. Automated fastener versus manually tied knots in minimally invasive mitral valve repair: impact on operation time and short- term results. J Cardiothorac Surg 2015; : 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modi P. Minimally invasive mitral valve repair: the Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital technique: tips for safely negotiating the learning curve. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013; : 6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thor J, Lundberg J, Ask J et al. Application of statistical process control in healthcare improvement: systematic review BMJ Qual Saf 2007; : 387–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modi P, Hassan A, Chitwood WR. Minimally invasive mitral valve surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014; : 943–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng DC, Martin J, Lal A et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional open mitral valve surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Innovations (Phila) 2011; (2): 84–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salis S, Mazzanti VV, Merlo G et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass duration is an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2008; : 814–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]