Abstract

Anorectal sepsis usually presents with anal abscesses, which may evolve to become anorectal fistulas. Most of these cases are either of cryptoglandular origin, or they develop secondary to inflammatory bowel diseases. A 32-year-old male patient applied to our Proctology Unit with severe anal pain and swelling. Three days before admission, leeches were applied to the hemorrhoidal swellings in a medical center. The abscess was drained with appropriate unroofing and search for any compartments. The patient recovered rapidly. The abscess culture and microscopy revealed mix flora with predominant Escherichia coli. After 6 months, he has been symptom-free with perfect healing of the surgical site. We need to check up on possible handicaps in our modern patient care policies that divert people to such methods. Nevertheless, such alternative methods should be regarded as nonscientific and out of context unless their efficacy and safety are documented.

INTRODUCTION

Anorectal sepsis usually presents with anal abscesses, which may evolve to become anorectal fistulas. Most of these cases are either of cryptoglandular origin, or they develop secondary to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Rare causes of anal abscess have also been reported, such as ingested bones or rectal duplication cysts [1, 2].

Leeches are flattened annelids or segmented worms that live in still, warm waters of the pond or in land, and they feed of blood or body fluids of other animals. Medicinal leeches (Hirudo medicinalis) have been used in traditional medicine for thousands of years to treat a wide range of diseases. Nowadays, leeches are used for only a few conditions, notably in the field of reconstructive or microsurgery, to salvage tissue flaps and skin grafts whose viability is threatened by venous congestion [3]. However, the application of leeches is associated with a risk of microbial infection, especially symbiotic Aeromonas spp., which may vary from minor wound complications to serious illnesses such as meningitis, bacteremia, and sepsis [4]. Furthermore, practitioners of alternative therapies may not be so familiar with basic surgical principles, such as antisepsis or antibioprophylaxis.

Here we report a case of anal abscess which developed acutely following leech therapy of hemorrhoids.

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old male patient applied to our Proctology Unit with severe anal pain and swelling which gradually increased during the last 48 hours. He was otherwise healthy with unremarkable medical history, no drugs or systemic illnesses. He had suffered from hemorrhoidal disease for the last few years, and three days before he applied to us, leeches were applied to the hemorrhoidal swellings in a small medical center. No proctologic work-up was done.

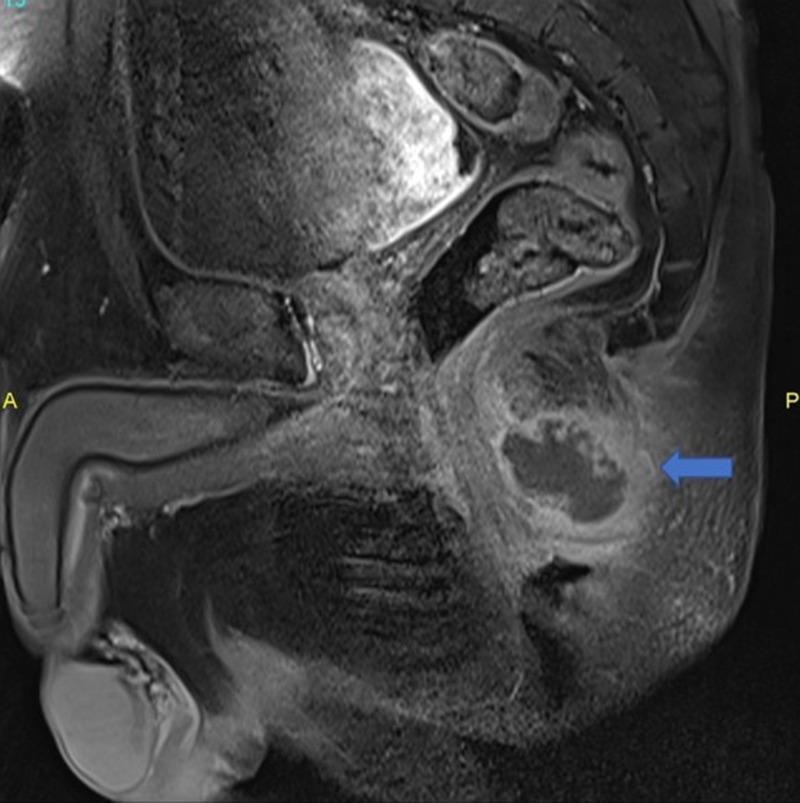

The patient was febrile (38.5°C) and restless. Proctologic examination revealed a painful swelling on the posterior midline, around which the leech bites could be seen (Fig. 1). He was immediately hospitalized, and a rapid pelvic MR, blood tests and anesthesia with epidural catheter were organized. Blood tests revealed a WBC count of 22 000/ml and sedimentation rate of 80 mm/h. A posterior perianal midline fluid collection measuring up to 4 × 3 cm was detected on MRI. The collection had thick and strongly enhancing walls with central diffusion restriction on diffusion weighted series, consistent with abscess. Inflammatory findings around the abscess were affecting both sides of the natal cleft (Fig. 2).

Figure 1:

Proctologic examination revealed a painful swelling on the posterior midline, around which the leech bites could be seen.

Figure 2:

Posterior midline perianal fluid collection with thick enhancing walls was demonstrated on sagittal postcontrast fat saturated T1 weighted image (arrow) consistent with abscess.

Under epidural anesthesia and in prone jackknife position, a complete anal examination and peroperative rectosigmoidoscopy were performed. A single dose of prophylactic ceftriaxone + metronidazole was given. The abscess was drained with appropriate unroofing and search for any compartments (Fig. 3). Pus and abscess wall samples were sent for microbiologic examination, asking for special attention for possible Auremonas spp.

Figure 3:

The abscess was drained with appropriate unroofing.

The patient recovered rapidly. The abscess culture and microscopy revealed mix flora with predominant Escherichia coli. After 6 months, he has been symptom free with perfect healing of the surgical site.

DISCUSSION

The discovery in 1884 of hirudin, an anti-coagulant substance in leech saliva, led to increased popularity of hirudotherapy for the treatment of venous insufficiency, varicose veins, hemorrhoids and other venous diseases. It is not surprising that proponents of alternative medicine lust for such methods, which usually lack scientific evidence for efficacy and safety, and therefore, do not exist in guidelines. The only reported series from India of leech application in thrombosed hemorrhoids also harbors severe methodological errors [5]. It is noteworthy that our public insurance system recently validated and started to pay for such applications. Our patient had undergone leech treatment in a medical center by a young practitioner who was not a surgeon or proctologist, at all. This is, unfortunately, a growing trend in this part of the world where easy gain without acquisition, difficult scientific education degrees, evidence base or adherence to guidelines is encouraged due to opportunistic motives.

It has been confirmed that the blood-sucking leech is a potential source of many human and animal pathogens including viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi [4, 6]. Because leeches may act as vectors of infectious agents, they should not be shared between patients, and even repetitive use for the same patient should be avoided [7]. To avoid serious bacterial complications, prophylactic antibiotics have been recommended before and during hirudotherapy [8]. Elimination of endosymbiotic bacteria by feeding leeches artificially with antibiotics was also tried [9]. Although we are skeptical about the meaning and impact of such measures taken for a worm with scientifically undefined efficacy, none had been undertaken in our patient, anyway. We also learned that skin antiseptics were not used either, possibly because most antiseptics such as povidone-iodine are highly toxic to leeches [10].

We need to check up on possible handicaps in our modern patient care policies that divert people to such methods. Nevertheless, such alternative methods should be regarded nonscientific and out of context unless their efficacy and safety are documented. Although this is the first reported case of anal abscess due to leech therapy of hemorrhoids, it readily warns us about many future and/or unreported ones.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Byrne CM, Lim JK, Stewart PJ. Ischiorectal abscess caused by ingested bones. ANZ J Surg 2004;74:818–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flint R, Strang J, Bissett I, Clark M, Neill M, Parry B. Rectal duplication cyst presenting as perianal sepsis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:2208–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porshinsky BS, Saha S, Grossman MD, Beery Ii PR, Stawicki SP. Clinical uses of the medicinal leech: a practical review. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:65–71. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.74297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bauters TGM, Buyle FMA, Verschraegen G, Vermis K, Vogelaers D, et al. Infection risk related to the use of medicinal leeches. Pharm World Sci 2007;29:122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhagat PJ, Raut SY, Lakhapati AM. Clinical efficacy of Jalaukawacharana (leech application) in Thrombosed piles. Ayu 2012;33:261–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nehili M, Ilk C, Mehlhorn H, Ruhnau K, Dick W, Njayou M. Experiments on the possible role of leeches as vectors of animal and human pathogens: a light and electron microscopy study. Parasitol Res 1994;80:277–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sartor C, Limouzin-Perotti F, Legre R, Casanova D, Bongrand MC, Sambuc R, et al. Nosocomial Infections with Aeromonas hydrophila from Leeches. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:E1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitaker IS, Kamya C, Azzopardi EA, Graf J, Kon M, Lineaweaver WC. Preventing infective complications following leech therapy: is practice keeping pace with current research? Microsurgery 2009;29:619–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mumcuoglu KY, Huberman L, Cohen R, Temper V, Adler A, Galun R, et al. Elimination of symbiotic Aeromonas spp. from the intestinal tract of the medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis, using ciprofloxacin feeding. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:563–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hokelek M, Güneren E, Eroglu C. An experimental study to sterilize medicinal leeches. Eur J Plast Surg 2002;25:81–5. [Google Scholar]