Abstract

Background

Acute postoperative pain remains a major clinical problem that affects patient recovery. Distal acupoint and peri-incisional stimulation are both used for relieving acute postoperative pain in hospital. Our objective was to assess and compare the effects of distal and peri-incisional stimulation on postoperative pain in open abdominal surgery.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Chinese databases CNKI and Wanfangdata were searched to identify eligible randomized controlled trials. Intensity of postoperative pain, opioid consumption and related data were extracted and analyzed using a random effects model. Risk of bias was assessed. Subgroup analyses were conducted when data were enough.

Results

Thirty-five trials were included, in which 17 trials studied distal stimulation, another 17 trials studied peri-incisional stimulation and one studied the combination of the two approaches. No studies that directly compared the two approaches were identified. Subgroup analysis showed that both distal and peri-incisional stimulation significantly alleviated postoperative resting and movement pain from 4 h to 48 h after surgery by 6 to 25 mm on a 100 mm visual analogue scale. Peri-incisional stimulation showed a better reduction in postoperative opioid consumption. No studies compared the effects of the combined peri-incisional and distal stimulation with either mode alone. Overall the quality of evidence was moderate due to a lack of blinding in some studies, and unclear risk of allocation concealment.

Conclusion

Both distal and peri-incisional modes of stimulation were effective in reducing postoperative pain. Whether a combined peri-incisional stimulation and distal acupuncture has superior results requires further studies.

Keywords: Distal acupoint stimulation, Peri-incisional stimulation, Postoperative pain, Open abdominal surgery

Background

Abdominal surgery is one of most common types of surgery and takes up to 50% surgery expenditure [1]. It is also one of the most painful types of surgery [2], and more than 80% of these patients suffer from moderate to severe postoperative pain[3, 4]. Severe abdominal pain significantly impacts on patient recovery and quality of life [5]. Providing effective pain relief in this group of patients is a major challenge for surgeons and anesthetists. Multimodal analgesic strategies of combined opioids and non-opioids drugs are the standard management, but cannot fully relieve pain and are associated with many adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and constipation [6]. Such adverse effects compound the common postoperative complications associated with abdominal surgery. To improve postoperative pain management, alternative, non-pharmacological therapies with minimal adverse effects on the gut are needed [7].

Acupuncture is one of the most common non-pharmacological therapies for pain [8, 9]. Strong evidence demonstrates that acupuncture treatment is effective for acute dental pain and postoperative nausea and vomiting [10, 11]. Some studies show that acupuncture has opioid-sparing effects making it a useful alternative or adjunct therapy to conventional management of postoperative pain. For managing postoperative pain, some studies stimulated acupuncture points (acupoints) on the arms and legs away from the pain sites, whereas other studies stimulated points at or close to the site of pain [12, 13]. Each has its advantages and disadvantages in clinical practice. It is unknown which mode of stimulation is better or if a combined peri-incisional and distal stimulation is better than alone. Acupoint stimulation, mostly used in the form of needling or acupressure, has been increasingly used to alleviate postoperative pain. A systematic review based on 15 studies and 1166 participants evaluated the effects of acupoint stimulation on postoperative pain, and found that acupuncture could significantly and safely reduce postoperative pain and reduce opioid consumption when compared with sham acupuncture [12].

Peri-incisional stimulation applies needles or uses a TENS (Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) or TENS like machine to deliver alternating current via cutaneous electrodes positioned near the painful site. There have been reviews of TENS on management of postoperative pain, and presented different results [14]. A systematic review of 11 studies with positive effects showed that adequate stimulation parameters could significantly reduce postoperative analgesic intake [15]. The other review showed however that TENS might reduce movement pain, but not postoperative resting pain [16].

The aims of this systematic review were 1) to compare the effects of peri-incisional stimulation with distal acupoint stimulation in treating postoperative pain; 2) to assess if combined distal acupuncture and peri-incisional stimulation was better than either alone.

Methods

This review adheres to the PRISMA guidance [17]. Randomized controlled clinical trials that studied the effects of distal stimulation or stimulation at the incision site, on postoperative pain in patients undergoing open abdominal surgery were searched in databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Chinese trials were searched in two Chinese Databases, CNKI and wanfangdata. The last electronic search was in September 2016.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

To be included, studies must have met the following criteria: 1. randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs); 2. patients underwent open abdominal surgery regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, type of anesthesia; 3. all forms of acupuncture and TENS or peri-incisional stimulation was used; 4. full text articles in English or Chinese; 5. must have reported postoperative pain (Mean and SD) or analgesic use (mean and SD) within 24 to 48 h postoperatively; 6. Control group consisted of no stimulation, sham stimulation, other forms of stimulation.

Exclusion criteria were

1. patients with other co-existing acute or chronic illness; 2. Laparoscopic surgery 3. duplicate articles; 4. stimulation on cutaneous nerves but not points close to the defined incision site; 5. articles only reported incidence of pain relief which needed opioid treatment, but without reporting the intensity of pain or dosage of opioid consumption.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes: 1. Postoperative pain including resting pain and pain on movement or cough at 6, 12, 24, or 48 h. 2. Postoperative opioid usage.

Secondary outcomes: 1. Adverse events of opioids.2. Anaesthetics usage. 3. Extubation time. 4. Days in hospital. 5. Duration in PACU (post-anesthesia care unit). 6. Return to activity.

Data collection

Two reviewers (Z.J and Z.R) independently screened the search results, selected studies, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias using a data extraction Excel file. The third reviewer (Z.Z) was consulted when disagreements occurred until a consensus was achieved. Then, data were checked by another reviewer (FB.J). The STRICATA (Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture) was extracted by XQ.W and WZ.W who both majored in acupuncture.

The authors were contacted if the data were insufficient. The data were not used in the review if no response was received from correspondence authors. In studies with more than two groups, we avoided double-counting of participants by following the guidelines for selecting studies and collecting data in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [12]. The following data were extracted: (i) types of stimulation, (ii) type of surgery, (iii) type of anesthesia, (iv) comparison groups, subgroups and number of patients, (v) pain scores including resting pain and pain on movement or cough at 4, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h after operation, (vi) total opioid analgesic consumption at 24, 48 and 72 h after operation, (vii) the incidence of opioid-related side-effects, such as vomiting, nausea, dizziness and pruritus, and (viii) anaesthetics usage and duration of recovery room stay. Pain scores were recorded and analyzed as visual analogue pain scores (VAS, 0–100 mm). Verbal rating pain scores (VRS, 0–10) or VAS (0–10) were converted to 0–100 mm VAS pain scores for analysis. All opioid analgesics dosages were converted to morphine equivalents (mg) [18]. Data reported in milligram per kilogram were converted to total milligram by multiplying the mean weight of the group. All data were recorded in mean and SD, and data expressed in SE were converted to SD. We extracted the data at the time which was closest to our pre-defined time points of 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h. Studies with multiple control groups were used in different comparisons. The number of participants was adjusted to reflect the multiple comparisons.

Quality assessment

The quality of studies was reviewed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias [12]. Areas of methodologic quality assessed included concealment of allocation (selection bias), random sequence generation (selection bias), blinding of the participants (performance bias), and blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias). We graded each domain as low risk, unclear (uncertain risk) or high risk, according to the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions provided by Higgins [17]. Intervention details such as acupuncture rationale, details of needling, treatment regimen, time selection, practitioner background and confidence, and adequacy of stimulation were extracted and evaluated by W.XQ and X.Q according to Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture [19].

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.2 software. Continuous data was analyzed and presented as mean difference with 95% confidence interval (CI), while dichotomous data was analyzed as RR (relative risk) with 95%CI using random effects model. Forest plots were performed to evaluate the effects. The percentage of heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistic. I2 values of 25, 50, and 75% represent low, moderate and high heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was conducted if sufficient data were available.

Results

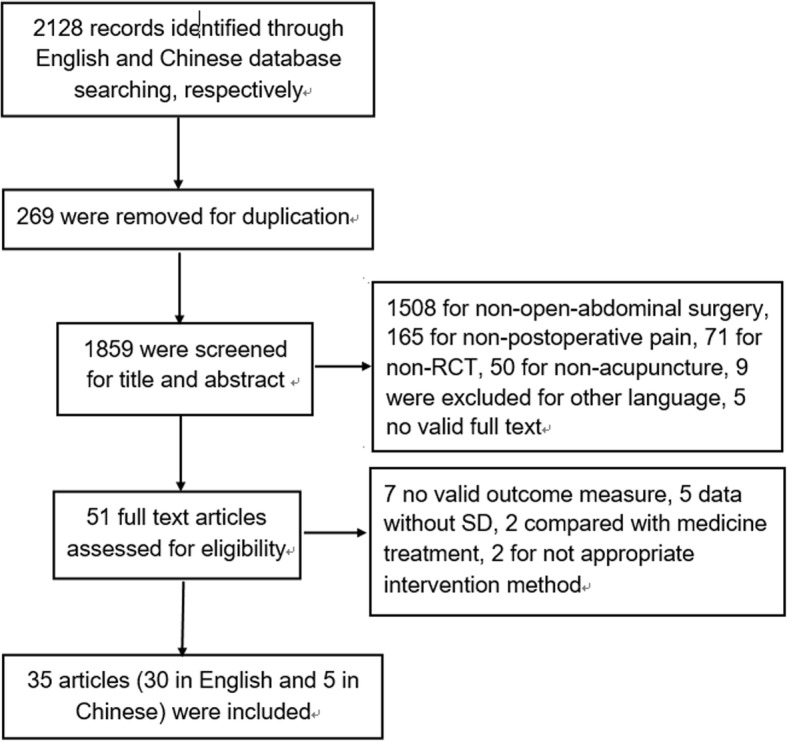

The flow chart of study screening is presented in Fig. 1. The search was first run for the original review in September 2015, updated in September 2016 and we combined both search results. A total of 2128 records were identified, and 269 were removed as duplicates. After screening from the titles and abstracts, 1808 were excluded and 51 potentially eligible studies were left for examination of the full text. Out of 51, 16 were excluded for the reasons outlined in Fig. 1. Finally 35 studies were included in this review, of which 5 were in Chinese and 30 were in English.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the search process and study selection

Study characteristics

As shown in Table 1, all participants included had upper or lower abdominal surgeries in this study. Seven studies included caesarean section [20–26], nine studies included gynecological surgery [27–35], three included cholestectomy [36–38], two included appendicectomy [39, 40], three included gastrointestinal surgery [41–43] and 10 studies didn’t mention the types of abdominal surgery. One study included patients undergoing both cesarean resection and vaginal delivery, and we only included data from caesarean section [24].

Table 1.

Study characteristics of all randomized, controlled trials included in the analysis

| Study ID | anesthesia type | Surgery type | Number of patients (A/C) | Stimulation style | Points used in the real acupuncture treatment | Sham/control | Duration | time select |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-incisional stimulation | ||||||||

| Binder et al. (2011) [23] | EDA | cesarean section | 22/20 | Hi-TENS | Incision: 2–3 cm distance from the wound | Non treatment | 24 h*1 day | Post-surgery:immediately after surgery, at least 24 h/one day |

| Bjersa and Andersson(2014) [50] | GA | pancreas resection | 9/11 | High frequency TENS | Incision:cranial of the incision, sacral of the incision, and columna innervating the dermatome for Th5 to Th9 | ‘increase stimulation until first sensitivity occurs and keep the stimulation as low as possible | At least 30 min, as much as possible | Post-surgery:two to four hours prior to epidural anlgesia ended |

| Smith et al. (1986) [30] | GA | caesarean section | 9/9 | TENS | Incision:the incision site | No electrical current was applied | 3 days, with the stimulator being turned off only occasionally, for short intervals (less than 15 min), | Post-surgery:As soon as the patient’s admission to the recovery room |

| Rakel et al. (2003) [31] | GA | abdominal surgery | 32/32 | TENS | Incision:parallel to the incision, | No stimulation | No reported | Post-surgery: After surgery,details |

| Hamza et al. (1999) [32] | GA | gynecologic surgery | 25/25 | TENS | Incision:surgical incision | No electrical current was applied | 30 min, every 2 h | Post-surgery::in the postanesthesia care unit for 30 min at intervals of 2 h or longer |

| Jaafarpour et al. (2008) [25] | SA | ceserean section | 54/54 | TENS | Incision: paraspinus muscles at T10-L1, and S2–4. 5 cm above and below the surgical incision, | Non-acu | continuously used for first 24 h except temporary breaks for walking, | Post-surgery: After surgery |

| Galloway et al. (1984) [36] | GA | Cholecystectomy with or without choledochotomy | 14/14 | tes | Incision:details | Nonsegmental TES | Not reported | Post-surgery: In the recovery room |

| Kayman-Kose et al. (2014) [24] | GA | cesarean section | 50/50 | TENS | Incision:above and below the incision line in women | no electrical current was transmitted in the placebo group | Not reported | Post-surgery: 30 min after childbirth was completed. |

| Gary et al. (1993) [33] | GA | gynecological operations. | 17/13 | TENS | Incision:2 cm away from and parallel to the incision | No current applied | 24 h, and 20 min on days 2 and 3 | Post-surgery: first 24 h after the operation. |

| Hershman et al. (1989) [37] | GA | cholecystectomy or colorectal surgery | 23/22 | TENS | Incision: | Non-functioning batteries | Not reported | Post-surgery: until the end of the second post-operative day, |

| Lim et al. (1983) [51] | GA | upper abdominal surgery | 15/15 | TENS | Incision:1 cm away from the incision | Reversed batteries | Not reported | Post-surgery: After surgery, the stimulator was turned on in the recovery room |

| Sodipo et al. (1980) [52] | GA | upper abdominal surgery | 15/15 | TENS | Incision:2 cm away from the incision | Non-acu | Not reported | Post-surgery: post operation, details |

| Conn et al.(1986) [39] | GA | Appendectomy | 15/13 | TENS | Incision:either side of the wound | The machine was switched off | Not reported | Post-surgery: At the end of the procedure |

| Hargreaves et al. (1989) [53] | Not mentioned | abdominal surgery | 25/25 | TENS | Incision: NR | No stimulation | Maybe 2 days | Post-surgery:depended on both time of return from surgery and time of dressing change. |

| Dougal T et al. (1991) [38] | GA | Cholestectomy | 15/15 | TENS | Incision:each side of incision | Non-acu | Not reported | Post-surgery: in recovery room |

| CUSCHIERI et al. (1985) [54] | GA | abdominal surgery | 53/53 | TENS | Incision:bilaterly in the paravertebral area;electroacupuncture: | The batteries are reversed | 30 min | Post-surgery: In the recovery room |

| Bjersa et al. (2015) [43] | EDA | COLON SURGERY | 15/13 | TENS | Incision:bilaterally of the incision,and columna innervating Th10 to L1 | “increase stimulation until first sensitivity occurs and keep the stimulation as low as possible” | no time limitations | Post-surgery: 1 h prior to EDA termination |

| Distal acupoint stimulation | ||||||||

| Hui et al. (2002) [20] | EDA | caesarean section | 20/20 | EA | Distal:Zusanli, Sanyinjiao | Non-acu | 30 min | Combined: pre-operation and 4 h or 8 h after surgery |

| Baoguo et al. (1997) [44] | GA | lower abdominal surgery | 25/25 | EA | Distal:hegu | No electrical current was applied | 30 min, every 2 h | Post-surgery::After surgery,details |

| He et al. (2007) [41] | GA | radical operation of intestinal cancer | 30/30 | EA | Distal:scalp | Non-acu | until the end of surgery | Pre-surgery: 20 min before surgery |

| Chen et al. (1998) [27] | GA | hysterectomy or myomectomy | 25/25 | EA | Distal:Zusanli | Nonacupoint and no-current | every 2–3 h | Post-surgery:On arrival in the PACU, |

| Lin et al.(2002) [45] | GA | lower abdominal surgery | 25/25 | EA | Distal:Zusanli, | with the indicator light on but with no actual current | 20 min | Pre-surgery: 20 min prior to anesthesia. |

| Feng et al.(2013) [28] | EDA | Gynecological surgery | 20/20 | EA | Distal:Zusanli, Sanyinjiao | Non-acu | Not reported | Pre-surgery:details |

| Feng et al.(2010) [29] | EDA | Gynecological surgery | 20/20 | EA | Distal:Zusanli, Sanyinjiao | Non-acu | Not reported | Pre-surgery: Before surgery |

| Adib-Hajbaghery et al. (2013) [40] | GA | appendectomy | 35/35 | Acupressure | Distal:Le7 | the button placed right in opposite side of the Le7 point (as sham point) | 1 h | Post-surgery: After surgery, started after the full patient’s consciousness |

| Kim et al.(2006) [35] | GA | Abdominal hysterectomy | 30/30 | Capsicum Plaster | Distal:Zusanli | inactive tape (5 _ 5 mm2) without PAS was applied to the Zusanli point of both legs. | 8 h per day/3 days | Combined: before induction of anesthesia |

| Hsiung et al.(2015) [42] | GA | subtotal gastrectomy | 26/28 | Acupressure | Distal:Neiguan (P6) and Zusanli (ST36) | Non-acu | Three12-min | Post-surgery:consecutive days following surgery. |

| Ntritsou et al. (2014) [46] | GA | radical prostatectomy | 35/35 | EA | Distal:LI4,ST36 | No current was applied | 30 min | Post-surgery: when the closure of the abdominal walls was initiated |

| Lee et al.(2011) [47] | GA | hysterectomy | 13/12 | EA | Distal:Zusanli (ST36) | no stimulation | 30 min | combined: before general anesthesia, and initiated once regained consciousness |

| Kotani et al.(2001) [48] | GA | elective upper and lower abdominal surgery | 50/48 | Acupuncture | Distal:BL18 –BL24 or BL20 –BL26 | a needle was positioned at each acupoint | 4 days | Combined: Before induction of anesthesia, |

| Wu et al. (2009) | SA | cesarean section | 20/20 | EA | Distal:Sanyinjiao(Sp6) | Non-acu | 30 min | Post-surgery: In the recovery room |

| Li et al. (2012) [22] | CESA | cesarean section | 60/60 | EA | Distal:auricular Shenmen point(TF4) | No current applied | 30 min | Combined: before surgery and 3 h, 8 h after surgery |

| Masatomo et al. (2003) [49] | GA | abdominal surgery. | 23/30 | Acupressure | Distal:neiguan, Zusanli, Sanyinjiao, and Gongsunpoints | Non-acu | Not | Post-surgery: On completion of surgery |

| Tsang et al.(2011) [34] | GA | total abdominal hysterectomy | 16/16 | auricular acupuncture | Distal: “uterus”“abdomen”“sympathetic” “shenmen” and“subcortex” | The sham TENS group received auricular TENS delivered to the following five inappropriate points: “teeth,” “tongue,” “mandible,” “eye,” and “face” | 20 min | Post-surgery: after surgery, |

| Combined distal and peri-incisional stimulation | ||||||||

| Sim et al. (2002) [26] | GA | gynaecologic lower abdominal surgery | 30/30 | EA | Distal:ST36 and PC6 bilaterally and subcutaneously along the skin incision. | No electrical current was applied. | 45 min | Post-surgery:group1\2:45 min before induction of anesthesia (GA)Group 3–45 min of postoperative |

CESA combined epidural and spinal anesthesia, EA electroacupuncture, EDA epidural anesthesia, GA general anesthesia, NR not reported, SA spinal anesthesia, TENS Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Twenty-six studies applied general anesthesia (76.5%), eight studies used spinal anesthesia or epidural anesthesia or combined spinal and epidural anesthesia, and one study did not mention the anesthesia type. The age and gender were comparable between intervention and control groups in all studies, and all trials were for adults.

STRICTA

Seventeen trials used distal acupoint stimulation [20–22, 27–29, 34, 35, 40–42, 44–49] and 17 trials used peri-incisional stimulation [23–25, 30–33, 36–39, 43, 50–54], and one trial combined distal and peri-incisional stimulation [26].

For distal stimulation, six types of stimulation were included: electroacupuncture (EA) [20–22, 27–29, 41, 45–47], transcutaneous acupoint electric stimulation(TEAS) [44], manual acupuncture [48], acupressure [40, 42, 49], auricular acupuncture [34] and capsicum plaster [35]. For peri-incisional stimulation, all studies stimulated at the peri-incisional area using the TENS or TENS like device.

Adequacy of distal acupuncture or peri-incisional treatment protocol

All studies described the details of treatment. None of the distal acupuncture studies provided a diagnosis according to Chinese medicine. Only two out of 17 distal studies gave references and literatures for their decision on acupuncture points selection [34, 44]. Most studies in peri-incisional group described the site as “around or 1 to 3cm away from skin incision”.

For distal acupuncture, seven acupoints were used, including Zusanli (ST36), Sanyinjiao (SP6), Neiguan (P6), Hegu (LI4), Gongsun(SP4), Shenmen (TF4), and Lanwei (Le7). ST36 and SP6 on the legs were two of the most frequently used distal acupoints, and used in eleven and six studies, respectively. Most of the studies used bilateral needling, except for seven studies [24, 33, 36, 37, 40, 51, 53] which did not state unilateral/bilateral needling details. Nine studies clearly stated how many needles were inserted, varying from 2 to 14, other studies didn’t offer the needle numbers.

With respect to the depth of needle insertion, three studies clearly described a depth of 0.2 cm for LI4 and 3-4 cm and 0.5-1 cm at acupoints ST36 and PC6, and subcutaneously for auricular acupuncture respectively [26, 46]. Other trials did not mention the depth of needle. Most studies stimulated at the highest intensity that patients could tolerate, while two studies in distal group described the intensity of “deqi” [42, 45]. This is not relevant to those peri-incisional stimulation where all of them use surface electrodes. The frequency and intensity of stimulation and retention time ranged widely among studies and were well reported in most studies.

Stimulation was initiated before surgery and after surgery in 11 studies and 24 studies respectively. Out of 11 studies that initiated before surgery, four studies maintained stimulating through the surgery [33, 35, 41, 48], three repeated acupuncture daily or every a few hours after surgery [20, 22, 47], two with no further stimulation [29, 45], while another two studies did not report details. No trial employed only intraoperative acupuncture. Out of the 24 studies that initiated after surgery, eight studies stimulated shortly from 12 min to 1 h after surgery, five studies stimulated daily during day 1 to day 4 postoperatively, and others didn’t describe the details.

Comparison groups

Of the 17 distal stimulation studies, five studies compared with sham treatment [27, 35, 40, 46, 48], seven studies compared with non-active treatment [20, 21, 28, 29, 41, 42, 49] and five studies compared with both forms of controls [22, 34, 44, 45, 47]. Two out of 17 studies compared different frequencies of stimulation [45, 47], and 1/17 compared EA with manual acupuncture [21]. In the 17 peri-incisional stimulation studies, 11 compared with sham [24, 30, 32, 33, 36–38, 43, 50, 51, 54], three compared with non-active stimulation [23, 25, 52], and three compared with both [31, 39, 53]. In addition, one study compared different intensities of stimulation [30], and one compared different frequencies of stimulation [32]. The control group of the combined distal and peri-incisional study was sham stimulation [26].

For the sham treatment, two studies (Bjersa 2014 and 2015) applied a low pulse intensity stimulus in their comparison group as the researchers felt this was more credible than a no stimulus placebo. Three distal studies [27, 34, 40] and one peri-incisional study [36] applied the stimulation to nonacupoint or inappropriate acupoints as the placebo control. The other 20 studies used a sham device that was similar to the active device without electrical current.

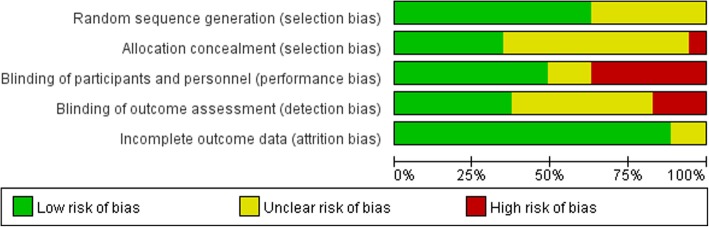

Risk of bias in included studies

A Risk of bias graph of each study is presented in Fig. 2. Four out of 35 studies were with an overall low risk of bias, and were studies of distal acupuncture. Fourteen studies were considered with a high risk of bias as one or more key domains were rated as ‘high risk’. One or more “unclear risks” were included in remaining 17 studies.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across included studies

Randomization and allocation concealment

Allocation sequence generation was rated as “low risk” in 23 studies, which was produced using a computer-generated random numbers table [21, 31, 34, 35, 42, 44–46, 48, 49], by an independent person blinded to the study design [23, 43, 50], a table of random numbers [22, 24, 28, 29, 33, 39, 41, 47] and a block design technique [36, 37].

Twelve of the 35 trials described allocation concealment [23, 24, 34, 35, 37, 39, 42, 43, 46–48, 50] and rated as “low risk”, the remaining trials did not report clear allocation concealment and were rated as “unclear”.

Blinding

Operators who delivered stimulations could not be blinded to the allocated treatment, while participants could be blinded by using placebo or sham control. Participants in all 11 studies that compared non-acupuncture with acupuncture treatment were not blinded, and were rated as “high risk”. In 21 trials, the blinding of outcome assessors was unclear, therefore performance bias was likely to have occurred.

Incomplete outcome data

All trials reported the complete outcome data, so attrition bias was low.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Distal acupuncture or Peri-incisional stimulation versus controls Intensity of postoperative pain at rest

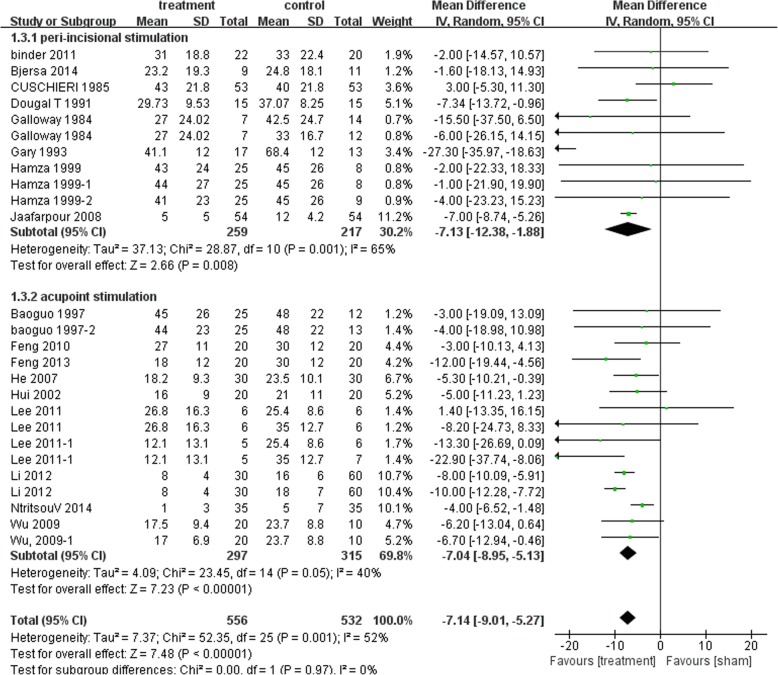

Postoperative pain at 4 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h was available for this comparison. Distal acupuncture was found significantly more effective than their controls in reducing postoperative pain intensity at rest at different time points[4 h: MD − 11.82 mm, 95% (− 15.47, − 8.16), I2 64%; 12 h: MD − 11.92 mm, 95%CI (− 13.58, − 10.26), I2 84%; 24 h: MD − 7.14 mm, 95%CI (− 8.95, − 5.13), I2 40%; 48 h: MD − 9.45 mm, 95%CI (− 12.41, − 6.50), I2 68%]. Peri-incisional stimulation also showed beneficial effects compared with their controls. [4 h: MD − 10.70 mm, 95% CI (− 15.32,-6.0), I2 45%; 12 h: MD − 13.52 mm, 95% CI (− 15.25, − 11.78), I2 92%; 24 h: MD − 7.13 mm, 95%CI (− 12.38, − 1.88), I2 65%; 48 h: − 10.32 mm, 95% CI (− 14.28, − 6.37), I2 47%]. Figure 3 showed the 24 h comparison data for postoperative pain at rest.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative resting pain intensity at 24 h: Subgroup analysis of Peri-incisional stimulation vs distal stimulation

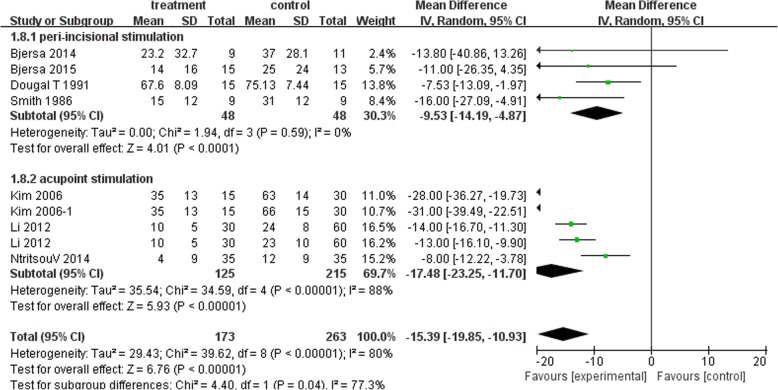

Intensity of postoperative pain on movement or cough

Eight studies had suitable data for this comparison. For postoperative pain on movement, distal acupuncture showed better effects than controls at 4 h [MD − 26.49 mm, 95% CI (− 35.56, − 17.42), I2 83%], 24 h [distal: − 17.48 mm, 95%CI (− 23.25, − 11.70), I2 88%] and 48 h [distal: − 16.61 mm, 95%CI (− 21.95, − 11.62), I2 82%]. Peri-incisional stimulation also showed beneficial effects compared with their controls at 4 h [MD − 4.46 mm, 95% CI (− 13.62, 4.70), I2 0%], 24 h [;-9.53 mm, 95% CI(− 14.19, − 4.87), I2 0%] and 48 h [− 14.02 mm, 95%CI (− 19.06, − 8.98), I2 0%]. Figure 4 showed the 24 h comparison data.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative pain intensity on movement at 24 h: Subgroup analysis of Peri-incisional stimulation vs distal stimulation

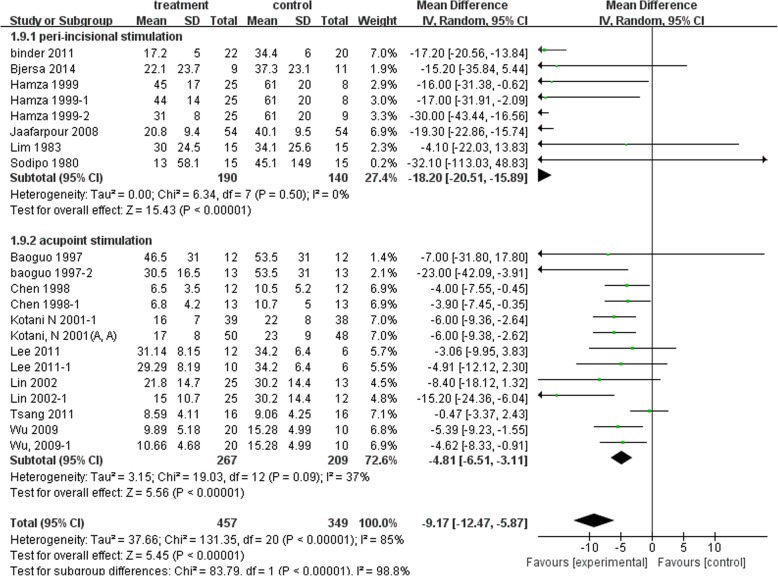

Postoperative opioid consumption

In Fig. 5, both distal acupuncture and peri-incisional stimulation showed significant reduction of postoperative opioid consumption at 24 h [distal: MD − 4.81 mg, 95%CI (− 6.51, − 3.11), I2 37%; Peri-incisional: MD − 18.2 mg, 95% CI (− 20.51, − 15.89), I2 0%].

Fig. 5.

Postoperative opioid consumption at 24 h: Subgroup analysis of Peri-incisional stimulation vs distal stimulation

Distal acupuncture versus Peri-incisional stimulation

No studies directly compared the two modes of stimulation. Fifteen studies in incision group and 20 studies in distal group had suitable data for sub-group comparisons. Subgroup analysis showed no significant difference between the effects of peri-incisional points and distal stimulation in alleviating postoperative resting pain at any time point (P = 0.17, 0.19, 1.0 and 0.06 at 4 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h respectively).

Postoperative cough pain at 24 h and 48 h showed no difference between two modes of stimulation. However, the distal acupuncture group had statistically significantly less pain on movement or cough at 4 h compared with incision group (Chi2 = 20.35, P < 0.00001).

Cumulative opioid consumption at 24 h postoperatively was significantly lower in incision group when compared with that in distal group (Chi2 = 88.82, P < 0.00001).

Peri-incisional or distal versus combination of both

No studies compared the combined of the two modes with either distal or peri-incisional stimulation alone. Only one study compared combination of the two stimulation modes with sham stimulation, and showed that preoperative stimulation could reduce 24 h morphine consumption. Subgroup analysis was not available.

Secondary outcomes

Opioid related adverse events

Seven studies in distal acupuncture group reported opioid related adverse events, while no study in peri-incisional group reported. The incidence of nausea significantly decreased in the distal acupuncture group compared with sham treatment (RR 0.7, 95%CI 0.55, 0.91, I2 = 39%), while vomiting was reduced without statistically significant difference (RR 0.64, 95%CI 0.36, 1.04, I2 = 0%). Four studies reported that acupuncture was associated with a lower incidence of postoperative dizziness (RR 0.67, 95%CI 0.51, 0.88, I2 = 18%), while it was not better than controls in the incidence of pruritis (RR 0.72, 95%CI 0.42, 1.23, I2 = 0%).

Distal or peri-incisional stimulation related side-effects

Three studies in distal group and one study in peri-incisional group reported side effects associated with the treatment [32, 35, 50, 52]. Side effects included erythema due to Capsicum plaster, a tingling and transient warm sensation, restricting activities and discomfort influencing sleep quality due to electrodes and wires. All of these side-effects were resolved spontaneously and were comparable with the control group. Seven studies reported no adverse effects or uncomfortable sensation. Others didn’t report acupuncture- related adverse effects.

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this meta-analysis, we found that distal acupoint stimulation and peri-incisional stimulation both had positive effects on reducing postoperative resting pain as well as pain on movement or cough up to 72 h postoperatively when compared with sham or non-treatment controls. In addition, both reduced postoperative opioid consumption at 24 h. Subgroup analysis showed no difference between peri-incisional or distal stimulation on postoperative pain reduction. However, peri-incisional stimulation was superior in reducing opioid consumption at 24 h whereas distal acupoint stimulation reduced opioid-related adverse effects, including nausea and dizziness. The pain intensity on movement at postoperative 4 h was lower in distal stimulation.

The level of evidence is low to moderate due to a moderate to high heterogeneity among studies and about half of the included trials had less than 25 participants in each study arm. The degree of risk of biases across trials also varied, with only four studies rated at overall low risks.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths of this review. First, we employed a comprehensive search of the Chinese and English databases with no language restriction. Secondly, we studied postoperative pain, both at rest and movement evoked, which is highly relevant to clinical practice. Thirdly, we restricted our analysis to studies on open abdominal surgery to reduce the heterogeneity introduced by different surgery types.

The current review also has several limitations. Firstly, we included trials using various stimulation techniques, manual, EA, acupressure and auricular acupuncture in distal acupuncture group. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by restricting stimulation to EA only or to English trials only and found this broad inclusion did not impact on the results of the review. Secondly, the heterogeneity was high in most comparisons, and we used a random effect model to address it. In addition, the broad difference of treatment duration and frequency among studies may contribute to the high heterogeneity. Thirdly, the number of participants randomized to each treatment group ranged from 9 to 60, with half of them having less than 25 participants in each study arm, which is a small sample size for pain studies [55]. Most of the studies did not justify the sample size calculation. Due to those limitations, we have downgraded the level of evidence and interpreted the data with caution.

Clinical relevance of distal acupuncture and peri-incisional stimulation

The site of delivering non-drug stimulation is highly relevant to clinical practice. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that examines the difference between incision and distal stimulation on postoperative pain and opioid sparing.

Peri-incisional stimulation is easy to use, noninvasive and often applied continuously for 24 h to 4 days after surgery, but the concerns of infecting the incision site are high. On the contrary, distal acupuncture is applied to arms and legs and could be applied before or after surgery and repeated every day for a short time without influencing the incision site, which is around abdomen in this review. Distal acupuncture could also be non-invasive. In one of the included studies, surface electrodes were applied to acupoints, i.e., TEAS. For the types of distal acupuncture, the review by Wu and colleagues (2016) found that conventional manual acupuncture and TEAS were associated with less postoperative pain than control treatment, while EA was similar to control; TEAS on acupoints was associated with significantly greater reduction in opioid analgesics use than control while conventional acupuncture and EA showed no benefit when compared with controls [56]. TEAS on distal acupoints may be an alternative in treating postoperative pain.

Either distal or peri-incisional stimulation was effective, however the later was more effective in opioid sparing. So the choice of which mode of stimulation will depend on the magnitude of the concerns over local infection and the importance of opioid sparing. Due to a lack of studies, we could not comment on whether a combination of peri-incisional and distal point stimulation is better than either alone.

Outcome data relevant to knowledge translation

To enable evidence being translated into practice, we have examined parameters that are essential to clinical practice in this review, such as the types of pain and safety data.

In recent years, increasing attention has been placed on movement-evoked pain as it is closely associated with postoperative thromboembolic complications and pulmonary dysfunction [57]. In addition, pain on movement adversely influences patient ambulation and early recovery in the early postoperative period [58, 59], and opioids were found relatively ineffective in treating pain on movement [58]. It is essential to study the effects of acupuncture on pain at rest as well pain on movement. In our review, only 9 studies (25.7%) included pain on movement as an outcome measure. Distal and peri-incisional stimulation was equally effective in pain on movement with the former being more effective at the early stage postoperatively than peri-incisional stimulation. Both present themselves as excellent adjunct non-pharmacological therapies in multimodal analgesic strategies.

Three studies in distal group and one study in peri-incisional group reported transient and minor adverse events, which is consistent with Sun’s review. A prospective survey studied the adverse effects of acupuncture and reported a rate of 14 per 10,000, and the events were minor [60]. Another survey also showed minor events after 34,407 acupuncture treatments [61]. Safety data from primary care cannot however be readily translated to the safety of acupuncture in acute and sub-acute settings. Peri-operative distal acupuncture or peri-incisional stimulation is likely to be safe, but future studies should report detailed safety data.

Implications for future studies

Considering the severe adverse events associated with current drug therapies for postoperative pain, the use of non-pharmacological interventions should be encouraged. Future studies could investigate the combination effects of distal and peri-incisional stimulation and directly compare the effects of distal and peri-incisional stimulation. Studies should report both resting pain and movement pain at different time points postoperatively. Factors that are related to evidence translation should be investigated, such as patients’ preferences and feasibility of integrating those therapies in to routine management of postoperative pain.

Conclusion

Perioperative distal acupoint or peri-incisional stimulation is safe and effective for postoperative pain and opioid sparing. They could be alternative or adjunct analgesic intervention. Which forms of stimulation to be used depends on the needs and availability of instruments and personnel. Distal acupuncture could be more effective in reducing movement pain at the early stage of post surgery, whereas peri-incisional stimulation was more effective in reducing postoperative opioids use. More studies with a large sample size that directly compare the two forms of stimulation are needed in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Ian Weeks and Ms Jenny Layton for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- CENTRAL

Cochrane central register of controlled trials

- EA

Electroacupuncture

- RCTs

Randomized control trials

- RR

Relative risk

- TEAS

Transcutaneous acupoint electric stimulation

- TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Authors’ contributions

MZ and ZZ participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. JZ obtained funding for the study, drafted the manuscript. YYW searched databases. ZJ and ZR independently screened the search results, selected studies, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias. FB. J re-checked the data. The STRICATA (Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture) was extracted by XQW and WZW who both majored in acupuncture. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Institutional Foundation of Jiangsu Provincial Hospital of.

TCM in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data (y2018rc21).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Juan Zhu, Email: juan_zhu@hotmail.com.

Qian Xu, Email: xuqian36@126.com.

Rong Zou, Email: njrr1982@hotmail.com.

Wenzhong Wu, Email: maerta_zhong@hotmail.com.

Xiaoqiu Wang, Email: xiaoqiuwang@foxmail.com.

Fangbing Ji, Email: fangbing2004@126.com.

Zhen Zheng, Phone: +61 3 9925 7167, Email: zhen.zheng@rmit.edu.au.

Man Zheng, Phone: +86-86617141, Email: man_zheng@sina.com.

References

- 1.Pfuntner A, Wier LM. Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011: Statistical brief #165[M]// healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP) statistical briefs. PubMed, vol. 2013.

- 2.Kehlet H. Surgical stress: the role of pain and analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:189–195. doi: 10.1093/bja/63.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ung JW, Lui JC. Postoperative pain management: Study of patients’ level of pain and satisfaction with health care providers’ responsiveness to their reports of pain. Nurs Health Sci. 2003;5:13–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Committee on Standards and Practise Parameters Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. An updatereport by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on acute pain management. Anes. 2010;116:248–273. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hines R, Barash PG, Watrous G, O’Connor T. Complications occurring in the postanesthesia care unit: a survey. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:503–509. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, Sehgal N, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–120. [PubMed]

- 7.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American PainSociety, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1444–1453. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derry CJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Systematic review of systematic reviews of acupuncture published 1996–2005. Clin Med. 2006;6:381–386. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-4-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee A, Chan SK, Fan LT. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point PC6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11. 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Naik PN, Kiran RA, Yalamanchal S, Kumar VA, Goli S, Vashist N. Acupuncture: An Alternative Therapy in Dentistry and Its Possible Applications. Med Acupunct. 2014;26(6):308–314. doi: 10.1089/acu.2014.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun Y, Gan TJ, Dubose JW, Habib AS. Acupuncture and related techniques for postoperative pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Brit J Anaesth. 2008;101(2):151–160. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong Lit Wan D, Wang Y, Xue CC, Wang LP, Liang FR, Zheng Z. Local and distant acupuncture points stimulation for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematicreview on the comparative effects. Eur J Pain. 2015;19(9):1232–1247. doi: 10.1002/ejp.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vance CG, Dailey DL, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. Using TENS for pain control: the state of the evidence. Pain Manag. 2014;4(3):197–209. doi: 10.2217/pmt.14.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll D, Tramer M, McQuay H, Nye B, Moore A. Randomization is important in studies with pain outcomes: systematic review of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in acute postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:798–803. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakel B, Frantz R. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on postoperative pain with movement. J Pain. 2003;4:455–464. doi: 10.1067/S1526-5900(03)00780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuster Jonathan J. Review: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews for interventions, Version 5.1.0, published 3/2011. Julian P.T. Higgins and Sally Green, Editors. Research Synthesis Methods. 2011;2(2):126–130. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macintyre PE, Ready LB. Acute Pain Management-A Practical Guide. 2. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders; 2001. Pharmacology of opioid; pp. 15–49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, Li Y, Wu T, et al. On behalf of the STRICTA revision group revised STandards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui X, ShouZ S, LiX X. Effects of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation on the postoperative analgesia with PCEA and recovery after surgery. Chinese J Clin Rehabilit. 2002;6(12):1784–1785. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu HC, Liu YC, Ou KL, Chang YH, Hsieh CL, Tsai Angela HC, Tsai HT, Chiu TH, Hung CJ, Lee CC, Lin JG. Effects of acupuncture on post-cesarean section pain. Chin Med J. 2009;122(15):1743–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li JZ, Li XZ, Wang MS, Li JP, Shi F, Yu HF. Effects of transcutaneous electrical stimulation of auricular Shenmen point on postoperative nausea and vomiting and patient-controlled epidural analgesia in cesarean section. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;92(27):1892–1895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binder P, Gustafsson A, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Nissen E. Hi-TENS combined with PCA-morphine as post caesarean pain relief. Midwifery. 2011;7(4):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayman-Kose S, Arioz DT, Toktas H, Koken G, Kanat-Pektas M, Kose M, Yilmazer M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain control after vaginal delivery and cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(15):1572–1575. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.870549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaafarpour MK, Khani A, Javadifar N, Taghinejad H, Mahmoudi R, Saadipour KH. The analgesic effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on caesarean under spinal anaesthesia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2008;2(3):815–819. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sim CK, Xu PC, Pua HL, Zhang G, Lee TL. Effects of electroacupuncture on intraoperative and postoperative analgesic requirement. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(2–3):56–65. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.2-3.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Tang J, White PF. The effect of location of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on postoperative opioid analgesic requirement: acupoint versus nonacupoint stimulation. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(5):1129–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng XM, Li J. Effect of electroacupuncture combined epidural anesthesia on plasma concentration of IL-1beta in patients undergoing gynecological surgery. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2013;33(5):611–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng XM, Li J, Wu Y. Effect of combined Electroacupuncture and epidural anesthesia in gynecological operation evaluated by bispectral index. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2010;30(2):150–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith CM, Guralnick MS, Gelfand MM, Jeans ME. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on post-cesarean pain. Pain. 1986;27(2):181–193. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rakel B, Frantz R. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on postoperative pain withmovement. J Pain. 2003;4(8):455–464. doi: 10.1067/S1526-5900(03)00780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamza MA, White PF, Ahmed HE, Ghoname EA. Effect of the frequency of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on the postoperative opioid analgesic requirement and recovery profile. Anesthesiology. 1999;91(5):1232–1238. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gary D, Kathleen AM. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in the treatment of postoperative pain and prevention of paralytic ileus. Clin Rehabil. 1993;7(3):218–221. doi: 10.1177/026921559300700307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsang HC, Lam CS, Chu PW, Yap J, Fung TY, Cheing GL. A randomized controlled trial of auricular transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for managing posthysterectomy pain. Evid-based Compl Alt. 2011;2011:276769. doi: 10.1155/2011/276769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim KS, Nam YM. The analgesic effects of capsicum plaster at the Zusanli point after abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(3):709–713. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000228864.74691.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galloway DJ, Boyle P, Burns HJ, Davidson PM, George WD. A clinical assessment of electroanalgesia following abdominal operations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;159(5):453–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hershman MJ, Cheadle WG, Swift RI et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) as adjunctive analgesia in patients undergoing elective abdominal procedures. Surg Res Communications 1989; 7(1): 65–69.

- 38.Dougal T. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation following cholecystectomy. Physiotherapy. 1991;77(10):715–722. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(10)60447-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conn IG, Marshall AH, Yadav SN, Daly JC, Jaffer M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation following appendectomy: the placebo effect. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1986;68(4):191–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Etri M. Effect of acupressure of ex-Le7 point on pain, nausea and vomiting after appendectomy: a randomized trial. J res med sci. 2013;18:482–486. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He BM, Li WS, Li WY. Effect of previous analgesia of scalp acupuncture on post-operative epidural morphine analgesia in the patient of intestinal cancer. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007;27(5):369–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsiung WT, Chang YC, Yeh ML, Chang YH. Acupressure improves the postoperative comfort of gastric cancer patients: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(3):339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bjersa K, Jildenstaal P, Jakobsson J, Egardt M, Fagevik OM. Adjunct high frequency transcutaneous electric stimulation (TENS) for postoperative pain management during weaning from epidural analgesia following Colon surgery: results from a controlled pilot study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(6):944–950. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baoguo W, Tang J, White PF, Naruse R, Sloninsky A, Kariger R, Gold J, Wender RH. Effect of the intensity of transcutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation on the postoperative analgesic requirement. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(2):406–413. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199708000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin JG, Lo MW, Wen YR, Hsieh CL, Tsai SK, Sun WZ. The effect of high and low frequency electroacupuncture in pain after lower abdominal surgery. Pain. 2002;99(3):509–514. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ntritsou V, Mavrommatis C, Kostoglou C, Dimitriadis G, Tziris N, Zagka P, Vasilakos D. Effect of perioperative electroacupuncture as an adjunctive therapy on postoperative analgesia with tramadol and ketamine in prostatectomy: a randomized sham-controlled single-blind trial. Acupunct Med. 2014;32(3):215–222. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2013-010498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee Daniel, Xu Hong, Lin Jaung-Geng, Watson Kerry, Wu Rick Sai Chuen, Chen Kuen-Bao. Needle-Free Electroacupuncture for Postoperative Pain Management. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/696754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotani N, Hashimoto H, Sato Y, et al. Preoperative intradermal acupuncture reduces postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting, analgesic requirement, and sympathoadrenal responses. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(2):349–356. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200108000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masatomo S, Muhammad IS, Nobutada M, Ozan A, Daniel IS. Minute sphere acupressure does not reduce postoperative pain or morphine consumption. Anesth Analg. 2003;96(2):493–497. doi: 10.1213/00000539-200302000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bjerså K, Andersson T. High frequency TENS as a complement for pain relief in postoperative transition from epidural to general analgesia after pancreatic resection. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014;20(1):5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lim AT, Edis G, Kranz H, Mendelson G, Selwood T, Scott DF. Postoperative pain control: contribution of psychological factors and transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Pain. 1983;17(2):179–188. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sodipo JO, Adedeji MBBS, Olumide O. Postoperative pain relief by transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) Am J Chin Med. 1980;8(1–2):190–194. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X80000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hargreaves A, Lander J. Use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for postoperative pain. Nurs Res. 1989;38(3):159–161. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cuschieri RJ, Morran CG, McArdle CS. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation for postoperative pain. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1985;67(2):127–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lesley AS, Anna DO, Henry JM. Teasing apart quality and validity in systematic reviews: an example from acupuncture trials in chronic neck and back pain. Pain. 2000;86:119–132. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu MS, Chen KH, Chen IF, Huang SK, et al. The Efficacy of Acupuncture in Post-Operative Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Modig J, Borg T, Karlstr G, Maripuu E, Sahlstedt B. Thromboembolism after total hip replacement: role of epidural and general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1983;62:174–180. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tverskoy M, Oren M, Dashkovsky I, Kissin I. Alfentanil dose-response relationships for relief of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:387–393. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199608000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu CL, Rowlingson AJ, Partin AW, et al. Correlation of postoperative pain to quality of recovery in the immediate postoperative period. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:516–522. doi: 10.1097/00115550-200511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adrian W, Simon H, Anna H, Edzard E. Survey of adverse events following acupuncture (SAFA): a prospective study of 32,000 consultations. Acupunct in Med. 2001;19(2):84–92. doi: 10.1136/aim.19.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hugh MP, Kate T, Stephen W, Mike F. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323:486–487. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]