Abstract

Introduction

Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) shortages and evidence of improved immunogenicity of two intradermal (ID) fractional IPV (fIPV) doses compared with one full intramuscular dose led to recommendations for fIPV delivery. To provide evidence on the economics of fIPV, we estimated the cost per child vaccinated using full-dose IPV compared with fIPV in routine and campaign settings. We evaluated the impact on costs of alternative devices facilitating ID administration, vaccine vial sizes, and prices.

Methods

We used an Excel-based model to estimate the commodity and delivery costs for providing IPV. Commodity costs included vaccine price per dose adjusted for wastage, prices for vaccine administration devices, and safety boxes. Delivery costs included storage costs at each level of the supply chain, transport costs for commodities between levels, and human resource costs for vaccine administration. Model inputs were obtained from various databases and published literature. All costs are reported in 2018 US dollars.

Results

In both campaign and routine settings, fIPV had a lower cost per child vaccinated than full dosing, despite the assumed higher vaccine wastage with fIPV in routine settings, and even when novel ID administration devices were used. In routine settings, costs per child fully vaccinated with fractional doses were 15% to 48% lower than those with full-dose delivery across different vial sizes. The cost per child vaccinated ranged from $1.84 to $2.65 for fractional doses, depending on the administration device, compared with $3.57 for full dose, when using 5-dose vials. The magnitude of cost reductions with fIPV relative to full-dose IPV was largest with smaller vial sizes and higher vaccine price.

Conclusion

Adopting fIPV can reduce costs per child vaccinated compared with using full doses, especially as IPV prices increase in the short term and more so when two full doses could be recommended in the future.

Keywords: Costing, Cost per child, Fractional dose, Fractional IPV, Inactivated poliovirus vaccine, Immunization

Abbreviations: AD, autodisable; bOPV, bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; cMYP, comprehensive multiyear plan for immunization; fIPV, fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IM fIPV, intramuscular administration of fractional doses of IPV; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; N&S, needle and syringe; OPV, oral poliovirus vaccine; tOPV, trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine; SAGE, strategic advisory group of experts; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund; US$, US dollars; VDPV, vaccine-derived poliovirus; WHO, World Health Organization

1. Introduction

As part of the Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013–2018, all countries that had been using trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (tOPV) were to switch to bivalent OPV (bOPV), omitting the type 2 antigen that causes most vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) cases [1], [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) be introduced before switching, to maintain immunity levels against poliovirus type 2; hence, all countries using oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) in their immunization programs were to add at least one dose of IPV into the schedule [3]. The next stage in the endgame will be OPV cessation and a change to IPV-only regimens. The global tOPV-to-bOPV switch was completed in April 2016; however, increased demand for IPV and problems in manufacturing resulted in a global vaccine shortage. The shortage resulted in delays in IPV introduction and a growing population susceptible to poliovirus type 2, thus increasing the risk of new circulating VDPV type 2 emergence [4]. The supply problems are anticipated to extend through 2019 and then to improve when new producers start supplying the market [5].

The IPV shortage led to an April 2016 recommendation by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization encouraging countries to evaluate the cost-benefits, trade-offs, and programmatic feasibility of using fractional doses (0.1 mL, which is one-fifth of a full dose) of IPV (fIPV) [4]. The proposed schedule was two fractional intradermal (ID) doses, e.g., at 6 and 14 weeks, compared with the standard single intramuscular (IM) dose at 14 weeks. Noting the successful experiences with fIPV introduction in India and Sri Lanka [6], [7] and the continuing IPV shortage, SAGE later recommended that other countries start preparing for fIPV introduction in routine immunization programs and, when deemed necessary, noted that outbreak response could also be conducted with fIPV [7]. In 2017, SAGE further recommended that regional and national immunization technical advisory groups endorse the two-dose fIPV schedule in national routine immunization programs [8]. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative emphasized that fIPV could be used in all types of polio immunization settings: routine, outbreak response, and supplementary immunization activities to increase coverage [9]. In 2018, SAGE provided an even stronger endorsement of fIPV, emphasizing that two ID fIPV doses are superior to one full dose of IM IPV [10]. The evidence for efficacy of the fractional dose is strong, with at least four studies showing that the two-dose ID fIPV schedule offers higher seroconversion rates than one full IM dose, when the ID dose is correctly administered [11], [12], [13], [14].

Use of fIPV not only allows stretching the vaccine supply but also may result in vaccine cost savings, as only 40% of the vaccine is used for a two-fractional-dose schedule compared with a one-full-dose schedule. Compared to 2018, IPV prices have increased in UNICEF’s tender for 2019 to 2022 for all vial sizes [5]. For a five-dose vial, the 2018 price per dose was $1.90, and this changes to $2.95 in 2019, $3.10 in 2020 and 2021, and $2.50 in 2022. This is more than a 50% increase in 2019 to 2021 prices compared with the 2018 price, making cost a potentially even greater consideration for immunization programs, donors, and financers. However, administering fractional doses can result in higher open-vial wastage rates, especially in routine settings in which multidose vials are opened but the entire contents are not administered within the 28-day period for which an open vial can be stored. According to UNICEF data on planned vaccine shipments in 2019 for Gavi, of the 64 countries procuring IPV, 36 countries procured five-dose vials, 19 procured 10-dose vials, and 9 procured single-dose vials [15]. Use of single-dose or five-dose vials is recommended for countries using fIPV [9], but supplies of these, particularly single-dose vials, is limited [5]. Countries currently using fIPV in routine immunization are administering the vaccine using 0.1-mL autodisable (AD) syringes, with vaccinators using the same administration technique as required for bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Because administration of an ID injection can be challenging, SAGE recommended that immunization programs explore the use of devices to facilitate ID administration of IPV, e.g., using jet injectors or ID adapters [7]. A disposable-syringe jet injector for ID administration (PharmaJet® Tropis®) received WHO prequalification in June 2018, and an ID adapter (West Pharmaceutical Services/Sanavita) has US Food and Drug Administration and CE mark regulatory clearance. WHO has procured a stockpile of devices sufficient for delivery of 5 million doses with the PharmaJet® Tropis® jet injector and 4.1 million doses with the ID adapter, and each device was recently used in large-scale fIPV campaigns in Pakistan and Nigeria, respectively.

To provide information to immunization programs on the cost implications of using ID fIPV, we conducted a cost outcomes analysis, with the objective of estimating the economic costs per child vaccinated using full versus fractional doses of IPV. These economic costs included the commodity and delivery costs of providing IPV to each child in campaign and routine settings and under several scenarios, including using alternative devices facilitating ID administration, vaccine vial sizes, and prices. Our modeling analysis can help stakeholders identify key variables that influence the estimated costs of different scenarios and inform decision-making about introduction and use of fIPV.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Overview

This costing study used the Vaccine Technology Impact Assessment model, an Excel-based model developed by PATH that estimates the commodity and delivery costs for alternative vaccine administration devices [16], [17]. Commodity costs included the vaccine price per dose, the prices for devices used for vaccine administration, and safety boxes for storing sharps waste. Delivery costs were the storage costs for commodities at each level of the supply chain, the transport costs for these commodities between supply chain levels, and human resource costs for vaccine administration. The analysis was done for one birth cohort in the 73 Gavi-supported countries in 2018 [18], for both campaign and routine delivery. The key model output was the average cost per child vaccinated. All costs are reported in 2018 US$ (US dollars).

The scenarios selected for modeling were campaign and routine immunization settings, and for each, we explored the effects of vaccine vial size, route of administration and device used, and dose regimens per child receiving all recommended doses in the schedule, based on the 2017 SAGE recommendations. We evaluated one immunization schedule in routine settings and two in campaign settings and assumed that single-, five-, or 10-dose vials could be used in either setting (Table 1).

Table 1.

IPV schedules, prices, cold chain volumes, and open-vial wastage rates, and healthcare worker salaries for the cost analysis.

| Input | |

|---|---|

| Doses in the IPV schedule—campaign settingsa | |

| Base case schedule | Full IM dose: 1 Fractional ID doses: 2 |

| Alternative schedule | Full dose: 1 Fractional doses: 1 |

| Doses in the IPV schedule—routine settingsa | |

| Base case schedule | Full IM dose: 1 Fractional ID doses: 2 |

| IPV pricesb | |

| 1-dose vial (2018 price) | $2.80 |

| 1-dose vial (2019 price)—base case for this analysis | $3.50 |

| 1-dose vial (2020 price) | $2.80 |

| 5-dose vial (2018 price) | $9.50 |

| 5-dose vial (2019 price)—base case for this analysis | $14.75 |

| 5-dose vial (2020 price) | $15.50 |

| 10-dose vial (2018 price) | $8.70 |

| 10-dose vial (2019 price)—base case for this analysis | $21.10 |

| 10-dose vial (2020 price) | $25.40 |

| IPV cold chain volume per vialc | |

| 1-dose vial | 15.7 cm3 |

| 5-dose vial | 20.0 cm3 |

| 10-dose vial | 24.6 cm3 |

| IPV open-vial vaccine wastage rates in campaign settingsd | |

| All vial sizes—full dose | 5% |

| All vial sizes—fractional dose | 5% |

| IPV open-vial vaccine wastage rates in routine settingsd | |

| 1-dose vial—full dose | 5% |

| 1-dose vial—fractional dose | 15% |

| 5-dose vial—full dose | 15% |

| 5-dose vial—fractional dose | 25% |

| 10-dose vial—full dose | 20% |

| 10-dose vial—fractional dose | 30% |

| Monthly salary for a health care worker | |

| Range of monthly salarye | $50 to $950 |

Abbreviations: fIPV, fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; SAGE, Strategic Advisory Group of Experts; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund.

Doses in the fIPV schedule were obtained from SAGE recommendations [7].

Vaccine prices per vial for Gavi-supported countries were obtained from UNICEF [5].

WHO prequalified vaccines [39].

WHO indicative wastage rate assumptions were used for campaigns and routine delivery of full-dose IPV [40]. For fIPV dose delivery, wastage rates were estimated based on the number of possible doses that could be obtained per vial.

The range of monthly salaries is provided since salaries differ by country.

2.2. Methods for estimating each cost component and key model inputs

2.2.1. Commodity costs

Commodity costs included the vaccine price per dose for each child vaccinated with all required doses in the schedule, taking into account open-vial vaccine wastage. Table 1 shows the IPV prices per vial for 2018 to 2020. The vaccine wastage rate depends on the vial size used, whether a full or fractional dose is administered, and whether the vaccine delivery setting is routine or campaign. We assumed lower open-vial vaccine wastage rates for smaller vial sizes, for full-dose delivery, and for campaign settings because open-vial wastage rates are affected by the number of doses in each vial and the number of children vaccinated at each session or during the 28-day period during which an opened IPV vial can be used under the Multi-dose Vial Policy [19]. For fractional doses, the price per dose also accounts for the fact that each full-dose equivalent can provide less or more than five fractional doses, depending on device design and the user’s technique when drawing doses [20]. Table 1 also shows the assumptions on vaccine wastage rates for different vial sizes and delivery settings. Most of the estimates reported in the results section of our evaluation were based on 2019 vaccine prices, but some comparisons used 2018 or 2020 prices.

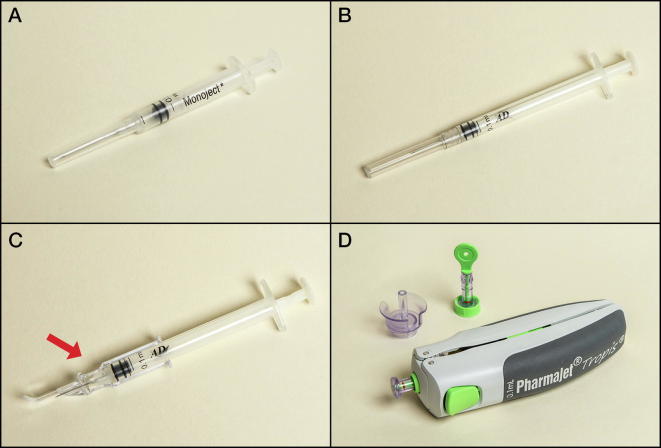

Commodity costs also included the prices for administration devices (Table 2). We modeled full-dose IM administration using a 0.5-mL AD syringe with fixed needle, and fractional ID dose administration using three devices: a 0.1-mL AD BCG syringe with fixed needle, an ID adapter with a 0.1-mL AD syringe with fixed needle, and a disposable-syringe jet injector (Fig. 1). The ID adapter controls the depth and angle of needle insertion to make injection of the vaccine into the dermal layer of the skin more reliable, while for the BCG syringe and needle, depth and angle are controlled by the person administering the vaccine. The jet injector is spring powered and uses a needle-free disposable syringe to inject a liquid stream of vaccine into the dermis.

Table 2.

Key input parameters for devices used for IPV administration.

| IM N&S | fIPV ID N&S | fIPV ID adapter | fIPV ID jet injector | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration devices (unit price; packaged volume) | 0.5-mL AD syringe with fixed needle ($0.039; 42 cm3) | 0.1-mL AD syringe with fixed needle ($0.041; 36 cm3) |

ID adapter and 0.1-mL AD syringe with fixed needle ($0.25 [base case], $0.15 [low price], $0.55 [high price]; 36 cm3) | Jet injector syringe—one per injection ($0.39; 21 cm3). Filling adapter—one per vial ($0.44; 42 cm3). Jet injector device—a reusable device ($362.20; 1,352 cm3). |

| Doses possible per IM single-dose equivalenta | 1.0 | 4.9 | 5.1b | 5.8b |

| Time (in seconds) taken by a health worker to administer a dose to a child | 32.6 | 54.4 | 61.0 | 63.6 |

Abbreviations: AD, autodisable; fIPV, fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; N&S, needle and syringe.

Number of doses per vial was based on the average number obtained in field use of fIPV (personal communication from Ed Clarke (May 1, 2019), [41].

More doses can be drawn from a vial than suggested by its labeling because of vial overfill and differences in device design and user technique.

Fig. 1.

Device used for IM administration: (A) 0.5-mL AD syringe with fixed 23G or 24G needle. Devices for ID administration of fractional IPV: (B) 0.1-mL AD syringe with fixed 26G or 27G needle (BCG syringe). (C) ID adapter on a conventional AD syringe (West Pharmaceutical Services/Sanavita). (D) Disposable-syringe jet injector with needle-free syringe and filling adapter (PharmaJet Tropis). Abbreviations: AD, autodisable; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine.

Table 2 shows the key input parameters for our model, assumptions for each administration device, and the commodity costs for these devices. For the ID adapter, the pricing in high-volume production has yet to be determined and could vary depending on the manufacturing and packaging approach used, so we evaluated the impact of the ID adapter price on the cost estimates. Our base case analysis assumed a price of $0.25 per device, and we also explored the impact on costs assuming two alternative price points of $0.15 and $0.55 per device. For other administration devices, just one price was used (Table 2).

We also investigated two scenarios for the jet injector: In the baseline scenario, we assumed that each health facility had one jet injector on site and each district had a spare injector to be used as a loaner in case of malfunction of an injector in that district. In the second scenario, we assumed each health facility had two jet injectors on site, with one being used as a spare. The jet injector consists of disposable and reusable components, and we assumed a useful life of five years for the reusable device. The number of times a device was used per year was dependent on country-specific inputs, which included the average number of children eligible for IPV vaccination at each health facility during a year. This was estimated by dividing the Expanded Programme on Immunization target population obtained from the WHO monitoring database [21] by the number of health facilities in each country obtained from national comprehensive multiyear plans (cMYPs) for immunization [22].

Finally, we included the cost of safety boxes for sharps disposal in the commodity costs. These costs were estimated based on the volume of sharps waste that is disposed of in a safety box after each vaccination using the different administration devices.

2.2.2. Delivery costs

Delivery costs included the storage and transport costs for the vaccines and administration devices, as well as the costs of health workers administering the vaccines. To estimate the storage costs, we assumed that each level of the supply chain had cold rooms at the national level, large refrigerators at regional and district levels, and small refrigerators at health facilities providing immunization services. For this standard set of cold chain equipment, which we did not vary by country, we estimated the capital cost using WHO prices for prequalified equipment and assumed a 10-year useful life [23]. We also obtained, from the same data source, the vaccine storage capacity of each piece of equipment and the energy used to run it during a 24–hour period. We then applied country-specific energy prices to estimate the annual costs of energy [24]. We summed the annualized capital costs and the annual energy costs and divided this by the net storage capacity to generate the cost per cubic centimeter of cold chain storage. We used similar methods to estimate the cost per cubic centimeter of cold boxes and vaccine carriers that are used for transporting vaccines.

Similarly, we assumed that countries used a standard type of refrigerated vehicle to transport vaccines between the national level and regional levels: four-wheel-drive vehicles between regions and districts, and motorcycles between districts and health facilities. Similar vehicles would be used for transporting immunization supplies, except that at the national level we assumed four-wheel-drive vehicles would be used. We assumed an average price for each of these vehicles using assumptions from cMYPs [22] and estimated annualized vehicle capital costs along with fuel and maintenance costs, which were estimated using country-specific fuel prices [25]. Transport costs also factored in average distances between supply chain levels and average number of delivery trips between supply chain levels, which were estimated in previous costing studies and were used for these calculations [26], [27]. Using these data, transport costs per cubic centimeter per kilometer were estimated.

For health worker costs, assumptions on the time taken to administer a vaccine using each device were obtained from time and motion data collected during fIPV clinical studies in The Gambia (personal communication from Ed Clarke, Medical Research Council Unit the Gambia, May 1, 2019) and Pakistan, as these are the only data from clinic-based settings where time use data are documented [28]. Country-specific salaries were obtained from the cMYPs [22]. We assumed 230 working days in a year and an eight-hour workday when calculating human resource hourly costs. For campaigns, the model also accounted for operational costs, which can include training, per diem expenses, and transport costs for vaccinators to session sites. These were also obtained from the cMYPs.

3. Results

3.1. Routine and campaign settings

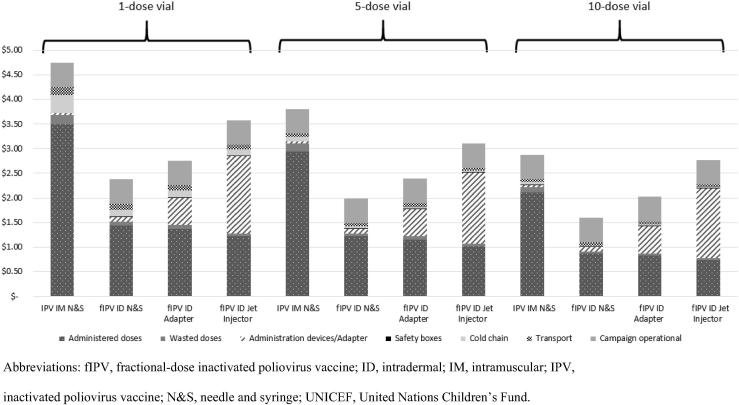

Using 2019 IPV prices, the cost per child vaccinated with all doses in the schedule decreased as vaccine vial size increased across all administration methods (IM and ID) for both full and fractional doses (Fig. 2). In addition, fractional doses always cost less per child vaccinated compared with full-dose administration. The costs, which included campaign operational costs, were highest for full-dose administration ($4.75) using single-dose vials and lowest for fractional dosing using 10-dose vials administered with ID needle and syringe (N&S) ($1.61). For IPV IM, fIPV ID N&S, or fIPV ID adapter, the cost of the vaccine is the largest share of costs, accounting for 43% to 82% of the total. However, when using the ID jet injector for fIPV, the costs for the administration devices (which include the annualized capital costs for the jet injector device and the disposable syringe and vial) are the largest share of costs.

Fig. 2.

Average cost per child vaccinated with IPV in a campaign setting using different sizes of vaccine vials (in 2018 US$). The model used one full dose administered intramuscularly and two fractional doses administered intradermally. Campaign operational costs were $0.50 per child vaccinated and did not vary across the administration devices or vial size used. These campaign operational costs also included the administration costs for vaccinators. The cost estimates were generated using the base case values for the administration devices (see Table 2) and UNICEF’s 2019 IPV prices. Abbreviations: fIPV, fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; N&S, needle and syringe; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund.

Use of devices that facilitate ID administration, though more expensive than fIPV ID injection with N&S, reduced costs relative to full-dose IM administration (Fig. 2). We also analyzed the costs per child vaccinated with a single-dose fIPV schedule in a campaign (alternative schedule in Table 1)—which may be recommended in an outbreak scenario if supplies are limited—and found that this further reduced the total costs per child vaccinated for fractional-dose administration compared with full-dose administration (results not shown).

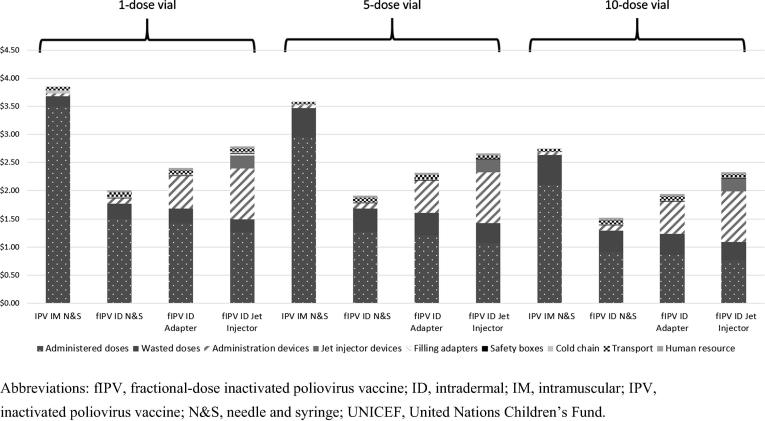

For routine immunization settings, findings were similar to those for campaigns regarding the relative costs for full versus fractional dosing and the impact of the vial size (Fig. 3). However, the value of vaccines wasted using fractional dosing was higher than for campaigns, given our assumption of higher open-vial vaccine wastage rates in routine settings. The absolute value of vaccines wasted was higher with 10-dose vials, but the total cost per child vaccinated remained lower when using the 10-dose vial because of the savings in vaccine price that comes with this larger vial. The cost per child vaccinated when using five-dose vials ranged from $1.91 to $2.66 for fractional doses administered using the alternative administration devices, compared with $3.59 for full dose. With single-dose vials, the cost per child vaccinated with fractional doses ranged from $2.01 to $2.78, compared with $3.85 for full dose (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Average cost per child vaccinated with IPV in a routine immunization program (in 2018 US$). The model assessed one full dose administered intramuscularly and two ID fractional doses. The cost estimates were generated using the base case values for the administration devices (see Table 2) and UNICEF’s 2019 IPV prices. Abbreviations: fIPV, fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; N&S, needle and syringe; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund.

The analysis also showed that even when accounting for higher wastage due to using fractional doses and the costs of the devices facilitating ID administration, fIPV was always less expensive than full-dose administration for all vial sizes in routine settings (Fig. 3). This is due to savings in the vaccine price with the reduced dose volume. Costs per child vaccinated with fractional doses was 15% to 48% lower than that with full doses in routine settings. Similar to the campaign analysis, for ID doses, costs were lowest for ID N&S and highest for the jet injector.

3.2. Scenario analyses

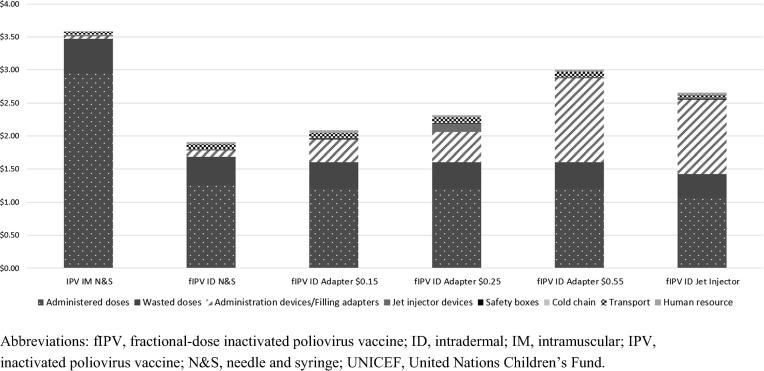

We examined use of a five-dose vial with ID adapters at different prices for the routine immunization setting and found that the cost per child vaccinated intradermally with fractional doses using this device was lower at all three ID adapter price points than full-dose IM vaccination. It was also lower than using the jet injector, except at the highest ID adapter price modeled, $0.55 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Average cost per child vaccinated with IPV in a routine immunization program using an ID adapter at different price points assuming a five-dose vial is used (in 2018 US$). The price for the vaccine was based on UNICEF pricing for 2019. Abbreviations: fIPV, fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; N&S, needle and syringe; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund.

We also compared the impact of the IPV prices on the cost per child vaccinated (Fig. 5). We used the UNICEF 2018, 2019, and 2020 vaccine prices for single- and five-dose IPV vials in a routine setting with a schedule where one full or two fractional doses are administered. As Fig. 5 shows, the cost per child vaccinated would increase with the higher vaccine prices in 2019 or 2020 compared to 2018 prices. In addition, the magnitude of cost savings from using fIPV compared with full dose increases as vaccine price increases.

Fig. 5.

Average cost per child vaccinated with IPV in a routine immunization program when either a 1- or 5-dose vial is used (in 2018 US$). The prices for the vaccine were based on UNICEF pricing for 2018, 2019, and 2020. Abbreviations: ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; N&S, needle and syringe; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund.

In addition, we estimated the annualized capital cost per child for the jet injector device in routine settings, which was determined by number of children eligible for IPV vaccination at each health facility and the number of devices at the health facility. The median number of children per facility eligible for IPV vaccination for the countries included in this analysis was approximately 380, resulting in annualized capital costs for the jet injector of approximately $0.23 per child vaccinated in our baseline scenario, when one device was placed at each health facility and a spare device was placed at the district. However, the capital costs could be significant in health facilities that serve small populations, with annualized jet injector capital costs estimated at approximately $3.50 per child when the health facility served approximately 25 children per year. For health facilities serving larger populations of 850 children per year, the capital costs would be as low as $0.10. These annualized capital cost results would roughly double in a second scenario where two jet injectors were given to each health facility.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have reviewed the evidence for the efficacy of using reduced doses of IPV and analyzed some of the cost implications [29], [30]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the cost implications for the currently recommended fractional-dose and full-dose IPV regimens, including both commodity and delivery costs. We demonstrate that providing two ID fIPV doses in campaigns or routine settings costs less per child vaccinated than one full dose. Vaccine delivered with ID fractional dosing consistently had a lower cost per child vaccinated than full dosing, despite the assumption of higher wastage for fIPV or the use of devices facilitating ID administration. The magnitude of the cost difference relative to full-dose IM injection depends primarily on the vaccine vial size used, and the difference is largest for the smaller vial sizes.

We also evaluated the impact of IPV pricing for Gavi-supported countries and found the costs for IM vaccination increased relative to those for fIPV with the higher IPV prices announced for 2019 and 2020 compared with the 2018 prices. The cost savings associated with ID fractional-dose administration were therefore magnified when compared with the full dose. It is anticipated that this cost differential will increase further if two full doses are recommended for both routine and campaign immunization settings as per the SAGE recommendation for a post-OPV immunization schedule [7]. Vaccine prices for non-Gavi-supported countries are much higher [31]; thus, savings from using fractional doses would be much larger for countries facing higher IPV prices.

We found that administration of fIPV reduced costs regardless of the device used. However, prices of the novel ID devices are important drivers of the cost estimates. For the ID adapter, while price reduction is possible if manufacturing and packaging are optimized, higher demand will be required for investments in scale-up. For jet injectors, an important cost driver is the use rate of the reusable device. In high-volume health facilities, the cost per child vaccinated will be less than in low-volume health facilities because the capital costs are spread over a larger population. In this analysis, we assumed that the jet injector device would be used only for IPV administration but use with other ID vaccines could reduce this capital cost. Other vaccines administered intradermally include BCG, rabies, and yellow fever. BCG vaccine is administered intradermally by N&S, and jet injector administration has been shown to produce similar immunogenicity [32]. However, the dosage of BCG for infants is different from that for fIPV (0.05 mL versus 0.1 mL, respectively), which would preclude use of the same device, unless a variable-dose device is developed.

Other studies have alluded to the economics of fractional or reduced dosing for other vaccines. For inactivated rabies vaccines, abbreviated regimens using ID administration have been recommended by SAGE for pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis and are cost-, dose-, and time-sparing while maintaining safety and clinical efficacy [33]. A study in Pakistan documented an 80% cost savings over the typical regimen [34], and a study in India found comparable cost savings with reduced-dose ID administration and found that patient adherence to the complete regimen nearly doubled [35]. Acute and chronic shortages of yellow fever vaccine have also prompted studies of fractional doses, administered either subcutaneously or intradermally. A modeling study concluded that administration of a reduced volume dose—0.1 mL rather than the 0.5-mL standard dose—could reduce the cost of the vaccine plus device for each yellow fever vaccination by approximately 67%, even if devices such as jet injectors were used [36]. Since 2015, yellow fever outbreaks have become more common [37]. In response, WHO recommended that yellow fever fractional-dose vaccination be considered in response to emergency situations [38]. WHO also noted that, as for IPV, fractional-dose vaccination is currently an off-label use, and for yellow fever vaccine, it is not recommended for routine immunization.

Our study has several limitations. First, we accounted for campaign operation costs but did not explicitly estimate the costs for training vaccinators to use the devices facilitating ID administration. Although some health workers are already giving the BCG vaccine intradermally, they would still require training on the new regimen and communication with caregivers, as for any vaccine introduction. Another limitation is related to the model inputs, as pricing for novel devices may vary from the estimates used in this analysis. However, we conducted scenario analyses for some of these inputs to evaluate how costs would change. In addition, due to lack of country specific data we used the same estimate for all countries on key inputs such as projected wastage rates, and yet actual wastage rates for full and fractional doses are likely to be country specific. For example, Sri Lanka, one of the first countries to introduce ID fIPV, has reported very low wastage rates with fractional dosing in a routine setting, which would further improve the cost savings compared with IM [6]. We also used estimates on the time spent to administer vaccines based on data from study settings in two countries; however, there may be variations in time to administer in actual programmatic use across countries. We did not account for the time costs for health workers for cleaning and maintaining reusable devices, though these are likely to be trivial. In addition, we did not model health impact, but we assumed similar efficacy between the different administration routes and devices. Lastly, we did not include current clinical studies that are evaluating the immunogenicity of IM administration of fractional doses of IPV (IM fIPV). We expect that if this approach proves feasible, our conclusions on costs would also apply to IM fIPV delivery, as key drivers such as the dose volume and device costs would be similar.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that using ID fIPV for campaign and routine immunization settings can reduce costs per child vaccinated compared with using IM full-dose administration, especially as IPV prices increase in the short term. Increased savings from using ID doses could be seen in the future should two full doses be recommended, rather than one full dose. These findings provide information that vaccine purchasers, ministries of health, and other global stakeholders can use to inform and guide decision-making about fIPV use, in conjunction with other considerations such as program capacity and vaccine supply availability.

Funding source

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA (grant numbers OPP1171001 and OPP1173857).

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Mercy Mvundura, Email: mmvundura@path.org.

Jui-Shan Hsu, Email: jhsu@path.org.

Collrane Frivold, Email: cfrivold@path.org.

Debra Kristensen, Email: dkristensen@path.org.

Darin Zehrung, Email: dzehrung@path.org.

Courtney Jarrahian, Email: cjarrahian@path.org.

References

- 1.Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Polio Eradication & Endgame Strategic Plan 2013–2018. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2013. http://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PEESP_EN_A4.pdf.

- 2.About the polio endgame strategic plan page. WHO website. http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/poliomyelitis/endgame_objective2/about/en/. Accessed 25 June 2018.

- 3.WHO. Polio vaccines. WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2016 Mar 25;91(12):145–168. https://www.who.int/wer/2016/wer9112/en/. [PubMed]

- 4.WHO. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, April 2016—conclusions and recommendations. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2016 May 27;91(21):265–284. https://www.who.int/wer/2016/wer9121/en/. [PubMed]

- 5.United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Inactivated Polio Vaccine: Supply Update. Copenhagen: UNICEF Supply Division; 2018. https://www.unicef.org/supply/files/Inactivated_Polio_Vaccine_Supply_Update.pdf.

- 6.Gamage D., Ginige S., Palihawadana P. National introduction of fractional-dose inactivated polio vaccine in Sri Lanka following the global “switch”. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2018;7(2):79–83. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.239418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, October 2016—conclusions and recommendations. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2016 Dec 2;91(48):561–584. https://www.who.int/wer/2016/wer9148/en/. [PubMed]

- 8.WHO. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, April 2017—conclusions and recommendations. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2017 Jun 2; 92(22):301–320. https://www.who.int/wer/2017/wer9222/en/. [PubMed]

- 9.WHO. Use of fractional dose IPV in routine immunization programmes: Considerations for decision-making [fact sheet]. Geneva: WHO; 2017. http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/poliomyelitis/endgame_objective2/inactivated_polio_vaccine/fIPV_considerations_for_decision-making_April2017.pdf?ua=1.

- 10.WHO. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, April 2018—conclusions and recommendations. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2018 Jun 8;93(23):329–344. https://www.who.int/wer/2018/wer9323/en/.

- 11.Resik S., Tejeda A., Lago P.M. Randomized controlled clinical trial of fractional doses of inactivated poliovirus vaccine administered intradermally by needle-free device in Cuba. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(9):1344–1352. doi: 10.1086/651611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammed A.J., AlAwaidy S., Bawikar S. Fractional doses of inactivated poliovirus vaccine in Oman. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2351–2359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resik S., Tejeda A., Sutter R.W. Priming after a fractional dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(5):416–424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anand A., Zaman K., Estívariz C.F. Early priming with inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) and intradermal fractional dose IPV administered by a microneedle device: a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6816–6822. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supply and logistics, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance webpage. UNICEF website. https://www.unicef.org/supply/index_gavi.html. Accessed 1 May 2019.

- 16.Mvundura M. Vaccine technology costs and health impact assessment tool [PowerPoint online]. Seattle: PATH; 2016. http://www.who.int/immunization/research/forums_and_initiatives/4_MercyM_MAP_vacctech_costs_health_impact_gvirf16.pdf.

- 17.Giersing B.K., Kahn A.L., Jarrahian C. Challenges of vaccine presentation and delivery: how can we design vaccines to have optimal programmatic impact? Vaccine. 2017;35(49 Pt A):6793–6797. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Countries eligible for support page. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance website. https://www.gavi.org/support/sustainability/countries-eligible-for-support/. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 19.WHO. WHO Policy Statement: Multi-dose Vial Policy (MDVP): Handling of multi-dose vaccine vials after opening. WHO/IVB/14.07. Geneva: WHO; 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/135972/WHO_IVB_14.07_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 20.Jarrahian C., Rein-Weston A., Saxon G. Vial usage, device dead space, vaccine wastage, and dose accuracy of intradermal delivery devices for inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) Vaccine. 2017;35(14):1789–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system—2018 global summary page. WHO website. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 22.Immunizations, vaccines and biologicals: Country information page. WHO website. https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/financing/countries/en/. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 23.WHO PQS catalogue page. WHO website. http://apps.who.int/immunization_standards/vaccine_quality/pqs_catalogue/categorypage.aspx?id_cat=17. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 24.Doing Business Data page. World Bank Doing Business website. http://www.doingbusiness.org/en/datascore. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 25.Pump price for gasoline (US$ per liter) page. World Bank website. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EP.PMP.SGAS.CD. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 26.Mvundura M., Kien V.D., Nga N.T. How much does it cost to get a dose of vaccine to the service delivery location? empirical evidence from Vietnam’s expanded program on immunization. Vaccine. 2014;32(7):834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mvundura M., Lorenson K., Chweya A. Estimating the costs of the vaccine supply chain and service delivery for selected districts in Kenya and Tanzania. Vaccine. 2015;33(23):2697–2703. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleem A.F., Mach O., Yousafzai M.T. Needle adapters for intradermal administration of fractional dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine: evaluation of immunogenicity and programmatic feasibility in Pakistan. Vaccine. 2017;35(24):3209–3214. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okayasu H., Sein C., Chang Blanc D. Intradermal administration of fractional doses of inactivated poliovirus vaccine: a dose-sparing option for polio immunization. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl 1):S161–S167. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hickling J, Jones R, Nundy N. Improving the affordability of inactivated poliovirus vaccines (IPV) for use in low- and middle-income countries: An economic analysis of strategies to reduce the cost of routine IPV immunization. Seattle: PATH; 2010. https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/TS_IPV_econ_analysis.pdf.

- 31.UNICEF. Inactivated Polio Vaccine. Copenhagen: UNICEF Supply Division; 2018. https://www.unicef.org/supply/files/2018_10_23_IPV.pdf.

- 32.Geldenhuys H.D., Mearns H., Foster J. A randomized clinical trial in adults and newborns in South Africa to compare the safety and immunogenicity of bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine administration via a disposable-syringe jet injector to conventional technique with needle and syringe. Vaccine. 2015;33(37):4719–4726. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2018—Recommendations. Vaccine. 2018 Sep 5; 36(37):5500–5503. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Salahuddin N., Gohar M.A., Baig-Ansari N. Reducing cost of rabies post exposure prophylaxis: Pakistan. PLoS NeglTrop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mankeshwar R., Silvanus V., Akarte S. Evaluation of intradermal vaccination at the anti rabies vaccination OPD. Nepal Med College J. 2014;16(1):68–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickling J, Jones R. Yellow fever vaccination: The potential of dose-sparing to increase vaccine supply and availability. Seattle: PATH; 2013. http://www.path.org/publications/files/TS_vtg_yf_rpt.pdf.

- 37.Emergency preparedness, response: Yellow fever page. WHO website. http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/yellow_fever/en/. Accessed 28 June 2018.

- 38.WHO. Fractional Dose Yellow Fever Vaccine as a Dose-sparing Option for Outbreak Response: WHO Secretariat Information Paper. Geneva: WHO; 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246236/WHO-YF-SAGE-16.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 39.WHO prequalified vaccines page. WHO website. https://extranet.who.int/gavi/PQ_Web/. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 40.Detailed product profiles page. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance website. https://www.gavi.org/about/market-shaping/detailed-product-profiles/. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 41.Bahl S., Verma H., Bhatnagar P. Fractional-dose inactivated poliovirus vaccine immunization campaign—Telangana state, India, june 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):859–863. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]