Abstract

Biochar as a promising adsorbent to remove heavy metals has attracted much attention globally. One of the potential adsorbents is biochar derived from punica granatum peels, a growing but often wasted resource in tropical countries. However, the immobilization capacity of punica granatum peel biochar is not known. This study investigated the physicochemical properties of punica granatum peel boichars pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C (referred as BC300 and BC600), and the efficiency and mechanisms of Cu(II) adsorption of five types of material treatments: BC300, BC600, soil only, and soils with biochar amendment BC300 and BC600, respectively, at the rate of 1% of the soil by weight. The results show that BC300 had higher yield, volatile matter content and organic carbon content, and larger pore diameter, but less ash content, surface area, pH, and cation exchange capacity than BC600. The Cu(II) adsorption capacity onto biochars and soils with biochar were greatly influenced by initial ion concentration and contact time. The Cu(II) adsorption capacity of biochar, independent of pyrolysis temperature, was around 52 mg g−1. The adsorption capacity of the soil amended with biochar nearly doubled (29.85 mg g−1) compared to that of the original soil (14.99 mg g−1), indicating superb synergetic adsorption capacity of the biochar-amended soils. The adsorption isotherms showed monolayer adsorption of Cu(II) on biochar, and co-existence of monolayer and multilayer adsorption in soils with or without biochar amendment. Results also suggest that the adsorption process is spontaneous and endothermic, and the rate-limiting phase of the sorption process is primarily chemical. This study demonstrates punica granatum peel biochar has a great potential as an adsorbent for Cu(II) removal in soil.

Subject terms: Environmental biotechnology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Copper (Cu(II)) is one of the heavy metals widely used in industrial manufacture1. Anthropogenic activities, such as mining and smelting, electroplating, petroleum refining and brass manufacture, are the main sources of Cu(II)2. Although Cu(II) is one of the essential micro-nutrients needed by living organisms3,4, the excessive doses of Cu(II) can cause serious problems to humans such as anaemia, hypoglycemia, stomach intestinal distress, and even kidney damage and eventual death5,6. Therefore, it is necessary to develop effective methods to remove Cu(II) from polluted water and soil. Recently, removal of Cu(II) from wastewater via adsorption is a promising technology with easy operation, high efficiency and relatively low-cost and insensitivity to toxic substances1, which has been adopted widely by water treatment plants3,7,8.

Biochars are produced through the pyrolysis of agricultural and forest residues with limited or no oxygen9. Biochar is widely used as an adsorbent in removing heavy metal ions of aqueous solution in the recent years10, which is due to its large surface area, high porosity and pH, and a large number of active functional groups such as hydroxy, carboxy, carbonyl11,12. Adsorption capacities are highly correlated with the properties of the biochars1. The properties of biochars are mainly determined by the feedstock material and the pyrolysis conditions (e.g. pyrolysis temperature)13,14. Several materials like plant residues, animal manures, industrial wastes and sewage sludge have been investigated as potential feedstock for biochar production15–18.

It is well known that China is one of the largest agricultural countries in the world. More than 260,000 tons of punica granatum are produced annually in China19. Most of the punica granatum residues are discarded, wasting a large amount of potential biomass resources as well as causing pollution to the environment. Therefore, it is necessary to find an effective way to deal with this problem. Using punica granatum peel as feedstock to produce biochar could be a feasible way to make bioenergy production with a low-cost, environment-friendly, and sustainable management of the punica granatum peel waste. However, so far no studies have been conducted on the production and application of biochar derived from punica granatum peels.

The overall aim of this work was to evaluate punica granatum peel biochar as a potential adsorbent to immobilize Cu(II) in contaminated soils. The objectives were to (1) investigate the effect of pyrolysis temperatures (300 °C and 600 °C, respectively) on the physicochemical properties of punica granatum peel biochar; (2) evaluate the influences of initial concentration and contact time on the sorption efficiency of Cu(II) onto adsorbents (i.e., BC300, BC600, soil, soil with BC300, and soil with BC600, respectively); and (3) understand the Cu(II) adsorption mechanisms (i.e., isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics) of these adsorbents.

Results and Discussion

The physicochemical and morphological characterization of biochars

In this study, the yield of biochar decreases from 46.6% to 28.0% as the temperature increases from 300 °C to 600 °C (Table 1). The decrease of biochar yield with tempeature is similar to the reports by Selvanathan et al.20 and Dai et al.21, which is attributed to the loss of volatiles and the condensation of aliphatic compounds because of increasing temperature22. The high yield of biochar is often considered as an important factor in practical application. At the same pyrolysis temperature (300 °C and 600 °C), punica granatum peels had a higher yield of biochar compared to that from orange peels (yield as 37.2% at 300 °C, 26.7% at 600 °C)23 and sugarcane bagasse (yield as 26.1% at 300 °C, 12.0% at 600 °C)24.

Table 1.

The physicochemical properties of pomegranate peel biochars pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C.

| Biochar | Yield (%) | Ash content (%) | Volatile matter (%) | Surface area (m2 g−1) |

Pore diameter (nm) | pH(1:2.5) | CEC (cmol kg−1) | Organic carbon (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC300 | 46.6 | 18.8 | 21.3 | 41.28 | 17.08 | 7.71 | 53.20 | 54.8 |

| BC600 | 28.0 | 39.4 | 6.7 | 195.32 | 3.34 | 10.76 | 74.11 | 46.7 |

Notes: BC300 and BC600, pomegranate peel biochar pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C, respectively. CEC stands for the cation exchange capacity.

It is also observed that the volatile matter content decreases from 21.3% to 6.7% when the pyrolysis temperature increases from 300 °C to 600 °C (Table 1) as the thermal degradation of biochar is gradually complete with the increase of pyrolysis temperature. In addition, ash content in BC600 is higher than that in BC300. In this work, punica granatum peel biochar has a higher volatile and ash content compared to rambutan peel biochar20 at the same pyrolysis temperature. Our results are consistent with the negative correlation between volatile and ash content25–27. These phenomena could be attributed to the volatilization of abundant inorganic components28.

In this work, biochar produced at the low-temperature (BC300) has a higher organic carbon content compared to that at the high-temperature (BC600) (54.8% vs. 46.7%) (Table 1). Our results are similar to reports that the organic carbon content decreased with the increasing pyrolysis temperature25,29, indicating that the enhancement of aromatization increases with the increasing temperature27. In this study, organic carbon content of punica granatum peel biochar is from 1.6 to 2.2 times higher than that of sugarcane bagass biochars24 at the same pyrolysis temperature. This may be related to the properties of the biomass materials.

Surface area of biochar increased from 41.28 to 195.32 m2 g−1 as temperature increases from 300 °C to 600 °C (Table 1). The increase of surface area of biochar with pyrolysis temperature have also been reported in the literature3,30,31. However, the increase in surface area of biochar showed a wave increase with increasing pyrolysis temperatures32–34. This phenomenon was related with destruction of both ester groups and aliphatic alkyl, and the exposure of aromatic lignin core as increasing pyrolysis temperature25. The pore diameter of BC600 (3.34 nm) is less than that of BC300 (17.08 nm), which is less than that of poultry manure biochars30 at the same pyrolysis temperature (300 °C and 600 °C). The main reason for this difference still remains to be further investigated. Additionally, our results are consistent with the opinion that there is a positive correlation between surface area and micropore volume35, and the pore size distribution is a key factor responsible for an increase in surface area in biochar36. Together with the biochar yield, the total surface area of biochar was estimated to be 18.86 and 54.60 m2 g−1 biomass for BC300 and BC600, respectively. Apparently, the surface area yield of BC600 was more than two times surface area of BC300. In addition, the SEM images showed that the surface morphology of biochars is featured by the numerous mesopores with varying sizes and shapes (Fig. 1). Compared with BC300, pores on BC600 were well developed, and the pore distribution on BC600 was relatively dense. Hence, it can be concluded that the surface structural changes in biochar are significantly influenced by pyrolysis temperature.

Figure 1.

SEM images of pomegranate peel biochars at 30 kev; magnification 500. Notes: BC300 and BC600, pomegranate peel biochar pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, pH increased significantly from 7.71 to 10.76 with the increasing pyrolysis temperature. Similar results have been reported by other researchers21,26,29,37. In the literatures, the range of pH was from 3.1633 to 12.1038 varied with pyrolysis temperature from 60 °C to 800 °C, with a mean value of 8.66. This phenomenon may be related with the release of the acidic surface groups during the pyrolysis process39. The alkaline pH of biochar has a liming effect on acidic soils, thereby probably increasing plant productivity39. High-ash biomass generates biochars with slightly greater CEC and charge density upon normalization of CEC to surface area26. In this study, CEC increased from 53.20 to 74.11 cmol kg−1 as pyrolysis temperature increase from 300 °C to 600 °C (Table 1). Komkiene et al.40 found an increase in the CEC of silver birch biochars from 5.09 cmol kg−1 to 5.71 cmol kg−1 with pyrolosis temperature from 450 °C to 700 °C, indicating the creation of the functional groups of hydroxyl and carboxylic acid in the oxidation process41,42. In contrast to our results, the CEC of some biochars decreased with increasing pyrolysis temperatures39,43, which could be due to the reduction of carbonylic and carboxylic functional groups44.

Elemental compositions and molar ratios of biochars have been extensively used to analyze the effects of pyrolysis temperature on the functional chemistry of biochars24. Table 2 shows the elemental composition and molar ratios of biochars pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C. Our results showed that the higher pyrolysis temperatures resulted in the biochar with higher carbon content, lower contents of hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen (Table 2). This feature was in agreement with findings of previous studies32,44,45. The increase in carbon content with temperature may be resulted from enhancement of carbonization46, while the lower content of hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen at high temperatures could have been attributed to the breaking of weaker bonds in biochar structure together with the loss of water, —OH, —C=O, —COOH and hydrocarbons during the carbonization process47. The H/C ratios decreased from 0.09 to 0.03, indicating the formation of structures containing saturated carbons such as aromatic rings48. The O/C and (O + N)/C ratios decreased with the increasing pyrolysis temperature, which is reflective of the reduction of oxygen-containing polar functional groups on biochar surface34,49.

Table 2.

The elemental composition of biochars pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C.

| Biochar | C (%) | H (%) | O (%) | N (%) | O/C | H/C | (O + N)/C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC300 | 46.64 | 4.06 | 39.31 | 1.34 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| BC600 | 62.34 | 1.82 | 36.11 | 0.25 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.58 |

Notes: BC300 and BC600, pomegranate peel biochar pyrolyzed at 300 °C and 600 °C, respectively.

Chemical characterization of different soil treatments

The chemical properties of three soil treatments are presented in Table 3. Compared with the control soil, the soils amended with the addition of 1% biochar (BC300 and BC600, respectively) have higher pH, CEC, and organic carbon content (Table 3). In contrast with soil with BC300, soil with BC600 result in greater changes in pH and CEC. An increase in soil pH has been reported with the application of biochar50,51. Increase of soil pH is due to the alkaline pH of biochar which is attributed to the presence of negatively charged carboxyl, hydroxyl and phenolic groups on biochar surfaces52. Increased soil pH with biochars contributes to the CEC increase by reducing the leaching of base cations in competition with H+ ions via enhanced binding to negatively charged functional sites of biochar53,54. Biochar-induced change in the physical and chemical properties of soil can further influence the sorption of metal ions26,49.

Table 3.

The chemical properties of three soil treatments.

| Treatment | pH | CEC (cmol kg−1) | Organic carbon (g kg−1) | Cu(II) (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| soil | 4.34 | 21.33 | 23.56 | 0.03 |

| soil with BC300 | 4.47 | 38.20 | 37.62 | 0.01 |

| soil with BC600 | 5.31 | 54.11 | 29.88 | — |

Notes: soil, control treatment; soil with BC300 and soil with BC600, soil amended with addition of BC300 and BC600, respectively in mass ratio of 1%. CEC stands for the cation exchange capacity.

Effect of initial metal ions concentration and adsorption isotherms

Current results are in agreement with the observation that the adsorption capacity of adsorbents has a close correlation with the initial concentration of metal ions in the reaction system55. As shown in Fig. 2, the adsorption efficiency of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents (soil, soil with BC300, soil with BC600, BC300, and BC600) increased with increasing initial Cu(II) concentrations. However, the equilibrium Cu(II) concentrations, where the adsorption rates start to level off, were different among adsorbents. The BC600 and BC300 has the highest equilibrium Cu(II) concentrations of about 500 mg L−1. In contrast, the equilibrium Cu(II) concentration of soil with BC300 and soil with BC600 was about 300 mg L−1, and that of the control soil was about 200 mg L−1. The adsorption capacity is attributed to the presence of active sites on the adsorbent surface7. There are greater available active sites with faster metal adsorption during the initial stage (i.e., at low Cu(II) concentration), whereas a few active sites are available with stable adsorption at the equilibrium stage7.

Figure 2.

Effect of initial Cu(II) concentration on adsorption capacity of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents (adsorbent dosage = 0.5 g, initial Cu(II) concentration = 10, 50, 100, 300, 500, 700 mg L−1, initial solution pH = 5.0 ± 0.1, contact time = 25 h, temperature = 25 °C).

Moreover, we found that the adsorption efficiency of Cu(II) onto adsorbents increases with increasing initial concentrations of Cu(II) (Fig. 2) and follows the order of BC600 (51.92 mg g−1) > BC300 (44.63 mg g−1) > soil with BC600 (29.19 mg g−1) > soil with BC300 (24.63 mg g−1) > soil (13.85 mg g−1) at the Cu(II) concentration of 700 mg L−1. Biochars pyrolyzed at the high-temperature have higher adsorption capacities of heavy metals compared with those pyrolyzed at low-temperatures40,56,57, which is due to biochar properties such as high pH, CEC, and surface area58. In contrast to our results, Li et al.29 found that Cd(II) adsorption capacities of water hyacinth derived biochars decreased with increasing pyrolysis temperature because biochars produced at low pyrolysis temperatures have numerous oxygen-containing functional groups that serve as effective binding sites for metal ions via complexation59,60. More interestingly, the adsorption capacity of Cu(II) onto soil amended with biochar doubled compared to the control soil in this study. Also, Feng et al.61 reported that the soils with bagasse biochar addition increased adsorption capacities. It is highly likely that biochar with higher CEC and negatively charged surface could enhance the electrostatic adsorption of Cu(II) in soil62. On the other hand, it is attributed to rich oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxylic and phenolic hydroxyl on the surface of biochar that can form stable surface complex with Cu(II)60.

Langmuir and Freundlich models are useful to evaluate the distribution of metal ions between the aqueous and solid phases57,63 and the maximum adsorption capacities of adsorbent62. Figure 3 shows plots of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms for adsorption of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents. According to the value of correlation coefficient (R2) in Table 4, the Langmuir isotherm model describes well the adsorption of Cu(II) onto both BC300 and BC600 (R2 > 0.98), which indicates that the monolayer adsorption occurs on homogeneous surfaces with no interactions among adsorbed metal ions64. Our results are consistent with those obtained by Ali et al.27. Furthermore, Komkiene et al.40 reported that biochars derived from scots pine and silver birch for the removal of Cu(II) fitted well with the Freundlich adsorption isotherms. The differences in absorption characteristics of biochars could be explained by different feedstocks65. In contrast to BC300 and BC600, the Cu(II) adsorption onto soil, soil with BC300, and soil with BC600 can well fit with both of the two models with the coefficients higher than 0.98, which suggested both the monolayer adsorption and the multilayer adsorption on adsorbent surfaces27,66. Furthermore, the prediction values of maximum adsorption capacity (qm) (Table 4) can well explain the experimental data (see Fig. 3). Compared with the Cu(II) adsorption capacities of other adsorbents reported in literature, the BC300 (51.02 mg g−1) and BC600 (53.19 mg g−1) exhibited quite a good adsorption performance (see Table 5). The value of 1/n is between 0 and 1 (Table 4), indicating that the adsorption process of Cu(II) onto adsorbents was favorable under the studied experimental conditions67. These results proved that BC300 and BC600 could be used as a potential sorbent for the removal of Cu(II) from contaminated soil.

Figure 3.

Plots for Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms for adsorption of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents (The legends of “Freundlich” are the same with that of “Langmuir”).

Table 4.

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm parameters for the adsorption of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents.

| Adsorbent | Langmuir model | Freundlich model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qm (mg g−1) |

KL (L mg−1) |

R2 | KF (mg g−1) |

1/n | R2 | |

| BC300 | 51.02 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| BC600 | 53.19 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| soil | 14.99 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.45 | 0.98 |

| soil with BC300 | 29.85 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.99 |

| soil with BC600 | 30.03 | 0.07 | 0.99 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

Table 5.

Comparison of the maximum monolayer adsorption of Cu(II) ions on various low-cost adsorbents.

| Type of Biomass | Pyrolysis temperature | Absorption condition | qm | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | pH | Temperature (°C) | (mg g−1) | ||

| pomegranate peel biochar | 300 | 5.0 | 25 | 51.02 | this study |

| pomegranate peel biochar | 600 | 5.0 | 25 | 53.19 | this study |

| Poplar sawdust | — | 4.0 | 25 | 3.24 | Sciban et al.88 |

| Coconut tree sawdust | — | 6.0 | 25 | 3.89 | Putra et al.89 |

| Canola straw biochar | 400 | 5.0 | 25 | 0.59 | Tong et al.3 |

| Soybean straw biochar | 400 | 5.0 | 25 | 0.83 | Tong et al.3 |

| Peanut straw biochar | 400 | 5.0 | 25 | 1.40 | Tong et al.3 |

| Hardwood biochar | 300 | 6.2 | 25 | 4.21 | Liu et al.70 |

| Pine wood biochar | 700 | 6.2 | 25 | 4.46 | Liu et al.70 |

| Corn straw biochar | 600 | 5.0 | 25 | 12.52 | Chen et al.90 |

| Hardwood biochar | 450 | 5.0 | 22 | 6.79 | Chen et al.90 |

| Hardwood biochar | 500 | 4.8 | 20 | 7.44 | Han et al.91 |

| Coir fibre | — | 5.5 | 30 | 9.43 | Shukla et al.92 |

| Jute fibres | — | 5.0 | 35 | 4.23 | Shukla et al.93 |

| Cotton fibre | — | 5.0 | 25 | 6.12 | Paulino et al.94 |

| Rice husks biochar | 300 | 5.0 | 24 | 6.26 | Pellera et al.6 |

| Dried olive pomace biochar | 300 | 5.0 | 24 | 7.07 | Pellera et al.6 |

| Silver birch | — | 4.0 | 30 | 0.13 | Bojarczuk et al.95 |

| Switch grass biochar | 500 | 4.8 | 20 | 7.12 | Han et al.91 |

| Compost biochar | 300 | 5.0 | 24 | 10.14 | Pellera et al.6 |

| Eggshell | — | 6.0 | 25 | 34.48 | Putra et al.89 |

| Orange waste | — | 5.0 | 24 | 10.26 | Pellera et al.6 |

| Tea waste | — | 5.0–6.0 | 25 | 48.00 | Amarasinghe et al.96 |

| Aquatic plant | — | 5.0–6.0 | 25 | 10.37 | Keskinkan et al.97 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | — | 6.0 | 25 | 3.65 | Putra et al.89 |

| Switch grass | — | 5.0 | 25 | 31.00 | Regmi et al.98 |

| Irish peat moss | — | 5.0–6.0 | 25 | 17.60 | Keskinkan et al.97 |

| Palm oil fruit shell | — | 6.5 | 20 | 60.00 | Hossain et al.99 |

| Groundnut shells | — | 5.0 | 60 | 4.46 | Shukla et al.92 |

| Wheat bran | — | — | 20 | 51.50 | Özer et al.100 |

| Enteromorpha compressa biochar | 500 | — | 25 | 75.10 | Kim et al.101 |

| Rambutan peels biochar | 600 | — | 25 | 217.30 | Selvanathan et al.20 |

| Residual biomass | — | 4.0 | — | 28.34 | Lezcano et al.102 |

| Root of rose biochar | 450 | 4.0 | 30 | 60.74 | Khare et al.103 |

| Hazelnut shell activated carbon | — | 6.0 | 50 | 58.27 | Demirbas et al.2 |

| Grape bagasse activated carbon | — | 5.0 | 45 | 43.47 | Demiral et al.104 |

| Orange peels activated carbon | — | 5.0 | 25 | 67.32 | Romerocano et al.105 |

| Olive stone activated carbon | — | 5.0 | 30 | 17.67 | Bohli et al.106 |

Notes: “–” stands for the data unreported in the literature.

Effect of contact time and adsorption kinetics

The relationship between contact time and the adsorption efficiencies of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents is illustrated in Fig. 4. The adsorption rate of Cu(II) onto those adsorbents followed three stages: (1) rapid adsorption during the initial 15 h; (2) slow adsorption lasting from 15 h to 35 h; and (3) equllibrium state starting at the 35th h. Hossain et al.68 found a large amount of Cu(II) can be bound rapidly onto the adsorbent at the initial stage. Lu et al.69 demonstrated that slow adsorption was attributed to the remaining vacant active sites that are difficult to be occupied because of the repulsive forces between Cu(II) on the solid and liquid phases. At the same contact time, the adsorption capacity varied with the five adsorbents (Fig. 4) and ranked in the following decreasing order: BC600, BC300, soil with BC600, soil with BC300, and soil. Comparison with control soil, the adsorption capacity increased by 1.7 times for soils with BC300 and 1.8 times for soil with BC600, respectively.

Figure 4.

Effects of contact time on adsorption capacity of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents (adsorbent dosage = 0.5 g, contact time = 5, 10, 15, 25, 35, 50, 65 h, initial Cu(II) concentration = 300 mg L−1, initial solution pH = 5.0 ± 0.1, temperature = 25 °C).

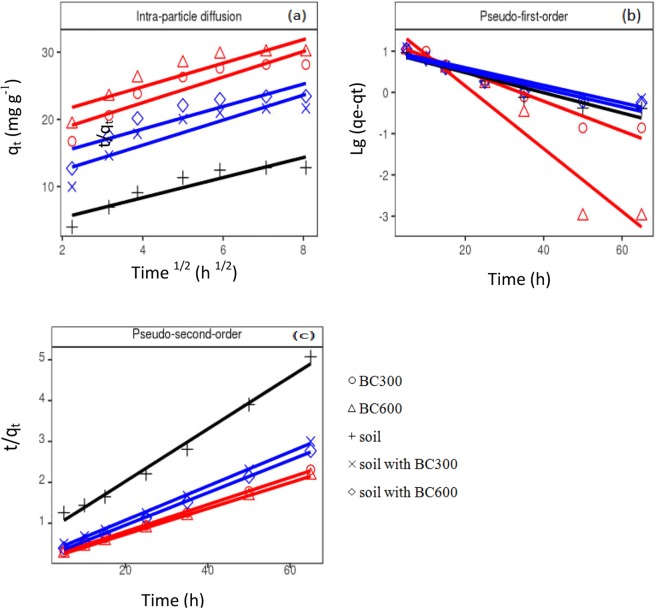

Kinetic model parameters of Cu(II) adsorption onto the five adsorbents are shown in Table 6. In terms of correlation coefficients (R2), the pseudo-second-order kinetic model was in good agreement with the kinetic experimental data (R2 > 0.99). A good linear relationship was presented between kinetic experimental data and pseudo-second-order kinetic model (Fig. 5c). In addition, the theoretical equilibrium adsorption capacities (qe) calculated using the pseudo-second-order kinetic model were consistent with the equilibrium adsorption capacities (Qe) obtained from the contact time study (Table 6). Several other Cu(II) adsorption studies using biochars such as rambutan peel, hardwood and corn stover biochar20,70 showed that the adsorption process followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The model assumes that the adsorption process consists of physical adsorption and chemical adsorption71, and chemical adsorption is the rate-limiting step72.

Table 6.

Kinetic model parameters for the adsorption of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents.

| Adsorbent | Qe | Intra-particle diffusion model | Pseudo-first-order model | Pseudo-second-order model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kp | C | R2 | qe | Kf | R2 | qe | Ks | R2 | ||

| (mg g−1) | (g mg−1 h−1/2) | (mg g−1) | (mg g−1) | (h−1) | (mg g−1) | (mg g−1 h−1) | ||||

| BC300 | 28.30 | 1.91 | 14.85 | 0.84 | 16.85 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 30.21 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| BC600 | 30.00 | 1.75 | 17.86 | 0.82 | 47.74 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 31.75 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| soil | 13.22 | 1.49 | 2.38 | 0.85 | 9.27 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 15.63 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| soil with BC300 | 22.34 | 1.86 | 8.72 | 0.81 | 10.65 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 23.92 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| soil with BC600 | 24.01 | 1.68 | 11.87 | 0.78 | 9.24 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 25.19 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

Figure 5.

Plots for the intra-particle diffusion, Pseudo-first-order and Pseudo-second-order sorption kinetics of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents.

To investigate the rate-limiting step of Cu(II) sorption onto the sorbents, the intra-particle diffusion model was employed to fit with the sorption kinetic data. The relationship between qt and t1/2 should be linear if intraparticle diffusion is involved in the sorption process. Moreover, if the linear relation passes through the base point, the rate limiting step is mainly controlled by intra-particle diffusion during the adsorption process73,74. In this study, the plot of qt and t1/2 is a multilinear plot (Fig. 5a), which did not pass through the base point, indicating that the sorption process consists of multiple stages75. Hafshejania et al.24 described the nitrate adsorption by intra-particle diffusion model as the three distinct linear portions–fluid transport, film diffusion, and surface diffusion. The intercepts (C) were nonzero (Table 6), indicating that the sorption processes might involve both the rapid surface sorption and slower intraparticle diffusion through the sorbents occurred simultaneously73. In addition, the intercept (C) values provides good information about the boundary layer thickness, that is, the larger intercept means the greater boundary layer effect76. The C value of BC600 was larger than the that of BC300 (Table 6). Similar results were reported by Kolodynska et al.73 who indicated that the biochars obtained at higher temperatures have the more evident boundary layer effect.

Thermodynamic studies

Thermodynamic analysis of the adsorption process is to investigate whether the process is spontaneous or not. In this study, thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents are listed in Table 7. The values of ΔG° presented here were in the range from −13.26 to −0.13 kJ mol−1. As shown in Table 7, the negative values of ΔG° imply that the adsorption processes are thermodynamically spontaneous in nature. The values of ΔG° were within the ranges of −20 to 0 kJ mol−1 59, which indicated that adsorption mechanism is dominated by physical adsorption77. The values of ΔG° gradually decreased with the increasing temperature (Table 6), which suggests that the higher temperature is more favorable for the adsorption process. The higher temperature provides sufficient energy for heavy metal ions adsorption on the surficial and interior layers of adsorbent63. The positive value of ΔS° indicates the increased randomness

Table 7.

Thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of Cu(II) onto different adsorbents.

| Treatment | Temperature | ΔG° | ΔH° | ΔS° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (kJ mol−1) | (kJ mol−1) | (J mol−1 K−1) | |

| 15 | −2.37 | |||

| BC300 | 25 | −5.97 | 101.08 | 359.22 |

| 35 | −9.56 | |||

| 15 | −3.44 | |||

| BC600 | 25 | −8.36 | 138.13 | 491.56 |

| 35 | −13.27 | |||

| 15 | −0.26 | |||

| soil | 25 | −1.06 | 22.69 | 79.70 |

| 35 | −1.86 | |||

| soil with BC300 | 15 | −0.13 | ||

| 25 | −1.93 | 51.69 | 179.92 | |

| 35 | −3.73 | |||

| soil with BC600 | 15 | −0.45 | ||

| 25 | −2.67 | 63.25 | 222.02 | |

| 35 | −4.19 |

at the solution-solid interface during the adsorption process53. The positive ΔH° shows that the adsorption process is endothermic. In this study, the values of ΔH° (Table 7) were within the ranges of 22.69 to 138.13 kJ mol−1. Generally, physical adsorption occurs mainly with the ΔH° value of less than 84 kJ mol−1, and chemical adsorption dominates with the ΔH° value in the range from 84 to 420 kJ mol−1 78. Therefore, the values of ΔH° presented in Table 7 indicated that adsorption of Cu(II) on the biochars (both BC300 and BC600) is dominated by chemical adsorption. In contrast, the adsorption of Cu(II) on the soil and soil with biochars is mainly governed by the physical adsorption.

Conclusions

The physicochemical properties of punica granatum peel biochars (BC300 and BC600) are greatly influenced by the pyrolysis temperature (300 °C and 600 °C, respectively). The Cu(II) removal efficiency and adsorption capacity onto biochars and soils with biochar were controlled by initial ion concentration and contact time. The maximum adsorption capacities of Cu(II) onto soil, soil with BC300, soil with BC600, BC300 and BC600 were 14.99, 29.85, 30.03, 51.02 and 53.19 mg g−1, respectively. These results revealed that the application of biochars (BC300 and BC600) can significantly improve the adsorption capacities of the soil for Cu(II). Adsorption characteristics of Cu(II) onto biochars fitted well by the Langmuir model,and adsorption characteristics of Cu(II) onto soil and soil amended with biochars were fitted well by both Langmuir and Freundlich models, indicating that there are monolayer adsorption and multilayer adsorption. Sorption kinetics of Cu(II) onto biochars and soils with biochar can be described by the pseudo-second-order mode. The thermodynamic parameters show that the adsorption is a spontaneous, endothermic, and entropy increasing process. This study indicates biochar derived from punica granatum peel is an effective and cheap adsorbent for the removal of Cu(II) in soils.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of biochars, soil, and solutions

Fresh red Punica granatum peels were collected from the Lintong, Xi’an City, Shan’xi Province, China. They were washed with deionized water, chopped into 1 × 1 cm2, and dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h. The pyrolysis process was conducted in a furnace (Fisher Scientific, USA) with N2 gas at 300 °C and 600 °C separately. The heating rate was set at 15~20 °C/min. The targeted temperatures (300°Cand 600 °C, respectively) are maintained for 2 h before cooling to room temperature. The biochars derived at 300 °C and 600 °C are referred to as BC300 and BC600, respectively. Biochar samples were ground and sieved to achieve the particle size of 0.75~1.00 mm for use in this study.

The testing soil was collected from the Ecological Station of the Central South University of Forestry and Technology (28°08’N, 113°00’E), Changsha City, Hunan Province, China. The soil sampling depth was 5~20 cm. The soil is red with a parent material from Quaternary sediments. The mixed sample soil was air-dried, ground and sieved to achieve the particle size of 1.75~2.00 mm.

A stock solution of 1000 mg L−1 Cu(II) was made by dissolving an appropriate amount of CuSO4∙5H2O in 0.1 mol L−1 NaCl solution, which was used as an electrolyte to control the ionic strength of metal ions. Then the stock solution was further diluted in distilled water to get solutions of desired concentrations at 10, 50, 100, 300, 500 and 700 mg L−1.

Characterization of biochars

The pyrolysis yield of biochars was calculated as the ratio of the weight of pyrolysis product to that of the original material. The ash content was calculated by determining the weight loss of 1 g biochar after its combustion in a crucible at 800 °C79. Following the same procedure, the volatile matter was determined at 950 °C80. The surface area and pore diameter of biochars were measured using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method81. The surface physical morphology was studied by a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (S-4800, Tokyo, Japan). The pH was measured using a volumetric ratio of 1: 2.5 (solid: liquid) by a pH meter (PXS-270, Shanghai, China). The cation exchange capacity (CEC) of biochars was determined using 1 mol L−1 NH4OAc (pH 7.0), and the concentration of exchangeable base cation was measured using an atomic absorption spectrometer (AAS) (PinAAcle 900, PerkinElmer, America). The organic content was obtained by the potassium dichromate oxidation heating method82. The elemental composition (C, H, N and O) of biochars was determined by an elemental analyzer (Vario EL, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Germany). Atomic ratios of (O + N)/C and H:C were calculated to evaluate the polarity and aromaticity of biochars.

Experimental design

We designed five experimental treatments: (1) soil, (2) BC300, (3) BC600, control treatment, (4) soil with BC300, and (5) soil with BC600. For treatments (4) and (5), 1000 g soil samples were weighted and put into the plastic pot (20 cm in top diameter, 12 cm in bottom diameter, and 15 cm in height). Biochar was added to the soil samples in a mass ratio of 1% (BC300 and BC600, respectively) and then mixed evenly. All treatments were repeated four times. For all the treatments, the soil moisture content was adjusted to 70% of the field capacity. After being incubated at 25 °C for 30 days, the treated soil was air-dried and sieved to achieve the particles of 1.75~2.0 mm.

Adsorption experiments

Adsorption isotherms experiments

The Langmuir (Eq. (1)) and Freundlich (Eq. (2)) isotherms are often adopted to model the adsorption process83:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where qe (mg g−1) is the adsorbed amount of metal ions at the equilibrium time, qm (mg g−1) is the maximum adsorption amount of metal ions when they form a monolayer on the adsorbent surface, Ce (mg L−1) is the metal ions concentration of the equilibrium aqueous phase, KL (L mg−1) is the Langmuir equilibrium constant, relating to the adsorption capacity and rate. qm and KL are evaluated by the intercept and slope of the plot of Ce/qe against Ce. KF (mg g−1) is the Freundlich constant, relating to the adsorption capacity, and 1/n is the intensity of the adsorbent. KF and 1/n are evaluated by the intercept and slope of the plot of lnqe vs. lnCe.

To examine sorption isotherms, 0.5 g of adsorbent (BC300, BC600, soil, soil with BC300, and soil with BC600, respectively) was mixed uniformly with 50 mL of solution with different concentrations of Cu(II) (i.e., 10, 50, 100, 300, 500, and 700 mg L−1) in a 100 ml centrifuge tubes, and the solution pH was adjusted to 5.0 ± 0.1 by 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH or 0.1 mol L−1 HCl. Furthermore, the mixture was shaken with a speed of 150 rpm at 25 °C by a thermostatic oscillator (ZC-100B, Shanghai, china). After 25 h, the extract was separated from the adsorbent by a centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 15 min at 25 °C, and the supernatant was filtered immediately through a 0.45 μm microfiltration membrane. The concentration of Cu(II) was determined by AAS at 324.7 nm. The amount of Cu(II) adsorbed on different adsorbents was calculated by Eq. (3)71:

| 3 |

where qe (mg g−1) is the amount of metal ions adsorbed at the equilibrium time; Ci and Ce (mg L−1) are the metal ions concentrations of the initial and equilibrium aqueous phases, respectively. V (L) represents the volume of solution, and m (g) is the mass of the adsorbent.

Adsorption kinetics experiments

Three kinetics models, the intra-particle diffusion, the pseudo-first-order, and the pseudo-second-order models, were used to investigate the adsorption kinetic behaviors of metal ions on the adsorbent. These three models can be expressed as Eqs (4,5 and 6), respectively75,84,85:

| 4 |

where qt (mg g−1) is the amounts of metal ions adsorbed at time t, Kp (g mg−1 h−1/2) is the rate constant of intra-particle diffusion obtained from the plot of qt against t1/2, and C (mg g−1) is the intercept reflecting the boundary layer effect.

| 5 |

| 6 |

where Kf (h−1) is the adsorption rate constant of pseudo-first-order obtained from the linear plots of log (qe − qt) against t, Ks (g mg−1 h−1) is the rate constant of pseudo-second-order obtained from the plot of t/qt against t.

Sorption kinetics of Cu(II) was determined by mixing 50 mL of 300 mg L−1 Cu(II) solution with 0.5 g of each adsorbent of BC300, BC600, soil, soil with BC300, and soil with BC600, respectively, in a 100 ml centrifuge tube. The mixture, with four replications, was shaken with a speed of 150 rpm at 25 °C by a thermostatic oscillator. After certain periods of time (1, 5, 10, 15, 25, 35, 50, and 65 h), the extract was separated from adsorbent by a centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 15 min at 25 °C, and the supernatant was filtered immediately through a 0.45 μm microfiltration membrane. The concentration of Cu(II) was determined by AAS. And the amount of Cu(II) adsorbed on different adsorbents was calculated by Eq. (3).

Adsorption thermodynamic experiments

To check whether the adsorption process is spontaneous, we calculated the thermodynamic parameters, such as enthalpy (ΔH°), entropy (ΔS°) and Gibb’s free energy (ΔG°) by Eqs (7) and (8)86,87.

| 7 |

| 8 |

Equation (7) can be written as:

| 9 |

where R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), T is the absolute temperature, Kθ is the thermodynamic equilibrium constant calculated by Eq. (10). ΔH° and ΔS° can be obtained from the plot of lnKθ against T, ΔG° can be calculated by Eq. (8).

| 10 |

The adsorption thermodynamic experiments were carried out by adding 0.5 g adsorbent (BC300, BC600, soil, soil with BC300, and soil with BC600, respectively) to 50 mL of 300 mg L−1 Cu(II) solutions in a 100 ml centrifuge tube. The mixture was shaken with a speed of 150 rpm at varying temperatures (15 °C, 25 °C, and 35 °C, respectively) for 25 h by a thermostatic oscillator. The extract was separated from the adsorbent by a centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 15 min at 25 °C, and the supernatant was filtered immediately through a 0.45 μm microfiltration membrane. The concentration of Cu(II) was determined by AAS. The amount of Cu(II) adsorbed on different adsorbents was calculated by Eq. (3).

All adsorption experiments were performed in duplicate under identical conditions, and the average values are presented in this study.

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by Open fund project of the innovation platform of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (No. 17K108). We appreciate the assistance of Dr. Yelin Zeng of the Central South University of Forestry and Technology for constructive comments on the draft.

Author Contributions

Q.C. and Z.H. designed the experiments, Q.C. performed the experiments and completed the first draft of the manuscript, Z.H. was responsible for data analysis and the graphics drawing, Z.H., S.L. and Y.W. revised the manuscript. All authors read and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data has been deposited in figshare and are available at 10.6084/m9.figshare.8320700.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Meng J, et al. Adsorption characteristics of Cu(II) from aqueous solution onto biochar derived from swine manure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014;21:7035–7046. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2627-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demirbas E, Dizge N, Sulak MT. Adsorption kinetics and equilibrium of copper from aqueous solutions using hazelnut shell activated carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2009;148:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2008.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong SJ, et al. Adsorption of Cu(II) by biochars generated from three crop straws. Chem. Eng. J. 2011;172:828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.06.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin H, et al. Copper(II) removal potential from aqueous solution by pyrolysis biochar derived from anaerobically digested algae-dairy-manure and effect of koh activation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016;4:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandah MI, Al-Rub FAA, Al-Dabaybeh N. The aqueous adsorption of copper and cadmium ions onto sheep manure. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2003;21:501–509. doi: 10.1260/026361703771953569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellera FM, et al. Adsorption of Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions on biochars prepared from agricultural by-products. J. Environ. Manage. 2012;96:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olgun A, Atar N, Wang S. Batch and column studies of phosphate andnitrate adsorption on waste solids containing boron impurity. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;222:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X, et al. Removal of Cu, Zn, and Cd from aqueous solutions by the dairy manure-derived biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013;20:358–368. doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-0873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann Johannes. Biochar for Environmental Management. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igberase E, Osifo P, Ofomaja A. The adsorption of copper(II) ions by polyaniline graft chitosan beads from aqueous solution: equilibrium, kinetic and desorption studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014;2:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2014.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan D, Jr., et al. Sorption of arsenic, cadmium, and lead by chars produced from fast pyrolysis of wood and bark during bio-oil production. J. Coll. Interf. Sci. 2007;310:57–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin J, et al. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on properties and environmental safety of heavy metals in biochars derived from municipal sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016;320:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaccari FP, et al. Biochar stimulates plant growth but not fruit yield of processing tomato in a fertile soil. Agr. Ecosyst Environ. 2015;207:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2015.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enders A, Hanley K, Whitman T, Joseph S, Lehmann J. Characterization of biochars to evaluate recalcitrance and agronomic performance. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;114:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahtalebi A, Sarrafzadeh MH, McKay G. An adsorption diffusion model for removal of copper(II) from aqueous solution by pyrolytic tyre char. Desalin. Water. Treat. 2013;51:5664–5673. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.769659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng J, et al. Physicochemical properties of biochar produced from aerobically composted swine manure and its potential use as an environmental amendment. Bioresour. Technol. 2013;142:641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang XJ, et al. Adsorption of copper(II) onto activated carbons from sewage sludge by microwave-induced phosphoric acid and zinc chloride activation. Desalination. 2011;278:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2011.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao XD, et al. Dairy-manure derived biochar effectively sorbs lead and atrazine. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:3285–3291. doi: 10.1021/es803092k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng XM, et al. Development status and strategic choice of Chinese pomegranate industry. Agr. Res. Appl. 2015;2:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selvanathan M, et al. Adsorption of copper(II) ion from aqueous solution using biochar derived from rambutan (nepheliumlappaceum) peel: feedforward neural network modelling study. Water. Air. Soil. Pollut. 2017;228:299. doi: 10.1007/s11270-017-3472-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Z, et al. The potential feasibility for soil improvement, based on the properties of biochars pyrolyzed from different feedstocks. J. Soil. Sediment. 2013;13:989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11368-013-0698-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su SL, et al. Production of hydrogen and light hydrocarbons as a potential gaseous fuel from microwave-heated pyrolysis of waste automotive engine oil. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2012;37:5011–5021. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdelhafez AA, Li J. Removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solution by using biochars derived from sugar cane bagasse and orange peel. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016;61:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2016.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hafshejani LD, et al. Removal of nitrate from aqueous solution by modified sugarcane bagasse biochar. Ecol. Eng. 2016;95:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung C, et al. Adsorption of selected endocrine disrupting compounds and pharmaceuticals on activated biochars. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013;263:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehmann J, et al. Biochar effects on soil biota – a review. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2011;43:1812–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali RM, et al. Potential of using green adsorbent of heavy metal removal from aqueous solutions: adsorption kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamic, mechanism and economic analysis. Ecol. Eng. 2016;91:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, et al. The effect of bioleaching on sewage sludge pyrolysis. Waste Manage (Oxford). 2015;48:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, et al. Preparation and characterization of biochars from eichornia crassipes for cadmium removal in aqueous solutions. Plos. One. 2016;11:e0148132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad MA, Puad NAA, Bello OS. Kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies of synthetic dye removal using pomegranate peel activated carbon prepared by microwave-induced koh activation. Water Resour. Ind. 2014;6:18–35. doi: 10.1016/j.wri.2014.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keiluweit M, et al. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:1247–1253. doi: 10.1021/es9031419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen B, Zhou D, Zhu L. Transitional adsorption and partition on nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants by biochars of pine needles with different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:5137–5143. doi: 10.1021/es8002684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jindo K, et al. Physical and chemical characterization of biochars derived from different agricultural residues. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:6613–6621. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-6613-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B, Chen Z. Sorption of naphthalene and 1-naphthol by biochars of orange peels with different pyrolytic temperatures. Chemosphere. 2009;76:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arcibar-Orozco JA, et al. Influence of iron content, surface area and charge distribution in the arsenic removal by activated carbons. Chem. Eng. J. 2014;249:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.03.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaterian M, et al. A new strategy based on thermodiffusion of ceramic nanopigments into metal surfaces and formation of anti-corrosion coatings. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2015;218:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.06.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komnitsas K, Zaharaki D, Pyliotis I, Vamvuka D, Bartzas G. Assessment of pistachio shell biochar quality and its potential for adsorption of heavy metals. Waste. Biomass. Valori. 2015;6:805–816. doi: 10.1007/s12649-015-9364-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z, et al. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from mines in China: pollution and health risk assessment. Sci. Tot. Environ. 2014;468:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Méndez A, Terradillos M, Gascó G. Physicochemical and agronomic properties of biochar from sewage sludge pyrolysed at different temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyr. 2013;102:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaap.2013.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Komkiene J, Baltrenaite E. Biochar as adsorbent for removal of heavy metal ions [cadmium(II), copper(II), lead(II), zinc(II)] from aqueous phase. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;13:471–482. doi: 10.1007/s13762-015-0873-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hale SE, et al. Effects of chemical, biological, and physical aging as well as soil addition on the sorption of pyrene to activated carbon and biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:10445–10453. doi: 10.1021/es202970x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang G, He Z, Xu W. A low-cost and high efficient zirconium-modified-Na-attapulgite adsorbent for fluoride removal from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;183:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.12.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen B, et al. Temperature sensitivity of black carbon decomposition and oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:3324–3331. doi: 10.1021/es903016y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kloss S, et al. Characterization of slow pyrolysis biochars: effects of feedstocks and pyrolysis temperature on biochar properties. J. Environ. Qual. 2012;41:990–1000. doi: 10.2134/jeq2011.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cantrell KB, et al. Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physicochemical characteristics of biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;107:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad M, et al. Trichloroethylene adsorption by pine needle biochars produced at various pyrolysis temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2013;143:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu H, et al. Removal and recycling of inherent inorganic nutrient species in mallee biomass and derived biochars by water leaching. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011;50:12143–12151. doi: 10.1021/ie200679n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun K, et al. Variation in sorption of propiconazole with biochars: The effectof temperature, mineral, molecular structure, and nano-porosity. Chemosphere. 2016;142:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang Q, et al. Aromatic and hydrophobic surfaces of wood-derived biochar enhance perchlorate adsorption via hydrogen bonding to oxygen-containing organic groups. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:279–288. doi: 10.1021/es403711y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glaser B, Lehmann J, Zech W. Ameliorating physical and chemical properties of highly weathered soils in the tropics with charcoal: A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2002;35:219–230. doi: 10.1007/s00374-002-0466-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rondon MA, et al. Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) increases with bio-char additions. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2007;43:699–708. doi: 10.1007/s00374-006-0152-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brewer, C. E. & Brown, R. C. Biochar. In Sayigh, A. (Ed.), Comprehensive Renewable Energy (Elsevier, Oxford, 2012).

- 53.Mukherjee A, Lal R. Biochar impacts on soil physical properties and greenhouse gas emissions. Agronomy. 2013;3:313–339. doi: 10.3390/agronomy3020313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taketani RG, et al. Bacterial community composition of anthropogenic biochar and Amazonian anthrosols assessed by 16S rRNA gene 454 pyrosequencing. A. Van Leeuw. J. Microbiol. 2013;104:233–242. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9942-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alothman ZA, Mu N, Ali R. Kinetic, equilibrium isotherm and thermodynamic studies of Cr(VI) adsorption onto low-cost adsorbent developed from peanut shell activated with phosphoric acid. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013;20:3351–3365. doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-1259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou D, et al. Effects of biochar-derived sewage sludge on heavy metal adsorption and immobilization in soils. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. Heal. 2017;14:681–695. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong X, Ma LQ, Li Y. Characteristics and mechanisms of hexavalent chromium removal by biochar from sugar beet tailing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;190:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, et al. Pb(II) biosorption by compound bioflocculant: performance and mechanism. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013;53:421–429. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.839403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilbert UA, et al. Biosorptive removal of Pb2+ and Cd2+ onto novel biosorbent: defatted carica papaya, seeds. Biomass. Bioener. 2011;35:2517–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atkinson CJ, Fitzgerald JD, Hipps NA. Potential mechanisms for achieving agricultural benefits from biochar application to temperate soils: a review. Plant. Soil. 2010;337:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0464-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feng D, et al. Preparation, characterization of bagasse-based biochar and its adsorption performance in tropical soils. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014;878:443–449. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.878.443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang TY, et al. Effect of biochar from rice straw on adsorption of Cd (II) by variable charge soils. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2012;31:1111–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding W, et al. Pyrolytic temperatures impact lead sorption mechanisms by bagasse biochars. Chemosphere. 2014;105:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inoue H, et al. Removal of phosphate by paper mill sludge: adsorption isotherm and kinetic study. Asian. J. Chem. 2014;26:3545–3552. doi: 10.14233/ajchem.2014.16227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan X, et al. Application of biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere. 2015;125:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu P, et al. Modification of biochar derived from fast pyrolysis of biomass and its application in removal of tetracycline from aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;121:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fosso-Kankeu E, et al. Gum ghatti and acrylic acid based biodegradable hydrogels for the effective adsorption of cationic dyes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;22:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hossain MA, et al. Biosorption of Cu(II) from water by banana peel based biosorbent: experiments and models of adsorption and desorption. J. Water. Sustain. 2012;2:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu D, et al. Kinetics and equilibrium of Cu(II) adsorption onto chemically modified orange peel cellulose biosorbents. Hydrometallurgy. 2009;95:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2008.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu Z, Zhang FS, Wu J. Characterization and application of chars produced from pinewood pyrolysis and hydrothermal treatment. Fuel. 2010;89:510–514. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2009.08.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hui KS, Chao CYH, Kot SC. Removal of mixed heavy metal ions in wastewater by zeolite 4A and residual products from recycled coal fly ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005;127:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kamari A, et al. Biosorptive removal of Cu(II), Ni(II) and Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions using coconut dregs residue: adsorption and characterisation studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014;2:1912–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2014.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sağ Y, Aktay Y. Mass transfer and equilibrium studies for the sorption of chromium ions onto chitin. Process. Biochem. 2000;36:157–173. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(00)00200-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kolodynska D, et al. Kinetic and adsorptive characterization of biochar in metal ions removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;197:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dwivedi C, et al. Copper hexacyanoferrate-polymer composite beads for cesium ion removal: synthesis, characterization, sorption, and kinetic studies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013;129:152–160. doi: 10.1002/app.38707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weber WJ, Morris JC. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. Asce. Sanit. Eng. Div. J. 1963;1:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mahmoodi NM, et al. Novel biosorbent (Canola hull): Surface characterization and dye removal ability at different cationic dye concentrations. Desalination. 2010;264:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2010.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Errais E, et al. Efficient anionic dye adsorption on natural untreated clay: kinetic study and thermodynamic parameters. Desalination. 2011;275:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2011.02.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dhaheri ASA, et al. The effect of nutritional composition on the glycemic index and glycemic load values of selected emirati foods. Bmc Nutrition. 2015;1:1–4. doi: 10.1186/2055-0928-1-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao R, Coles N, Kong Z, Wu J. Effects of aged and fresh biochars on soil acidity under different incubation conditions. Soil. Till. Res. 2015;146:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2014.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brunauer S, Emmett PH, Teller E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938;60:309–319. doi: 10.1021/ja01269a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alguacil MM, et al. Changes in the composition and diversity of AMF communities mediated by management practices in a Mediterranean soil are related with increases in soil biological activity. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2014;76:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Štefušová K, et al. Removal of Cd2+ and Pb2+ from aqueous solutions using bio-char residues. Nova Biotechnol. et Chimica. 2012;11:139–146. doi: 10.2478/v10296-012-0016-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kolasniski KW. Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption gelÖster stoffe kungliga svenska vetenskapsakademiens. Fresen. Z. Analy. Chem. 2001;179:118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ho YS, Mckay G. Sorption of dye from aqueous solution by peat. Chem. Eng. J. 1998;70:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0923-0467(98)00076-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jawad AH, et al. Adsorption of methylene blue onto activated carbon developed from biomass waste by H2SO4 activation: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Desalin. Water. Treat. 2016;57:25194–25206. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2016.1144534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arias F, Sen TK. Removal of zinc metal ion (Zn2+) from its aqueous solution by kaolin clay mineral: a kinetic and equilibrium study. Colloid. Surface. A. 2009;348:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sciban M, Klasnja M. Wood sawdust and wood originate materials as adsorbents for heavy metal ions. Holz. Roh. Werks. 2004;62:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s00107-003-0449-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Putra WP, et al. Biosorption of Cu(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) ions from aqueous solutions using selected waste materials: adsorption and characterisation studies. J. Encapsul. Adsorpt. Sci. 2014;4:25–35. doi: 10.4236/jeas.2014.41004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen X, et al. Adsorption of copper and zinc by biochars produced from pyrolysis of hardwood and corn straw in aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:8877–8884. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Han Y, et al. Heavy metal and phenol adsorptive properties of biochars from pyrolyzed switchgrass and woody biomass in correlation with surface properties. J. Environ. Manage. 2013;118:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shukla PM, Shukla. SR. Biosorption of Cu(II), Pb(II), Ni(II), and Fe(II) on alkali treated coir fibers. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2013;48:421–428. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2012.691933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shukla SR, Pai RS. Adsorption of Cu(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) on dye loaded groundnut shells and sawdust. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2005;43:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2004.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paulino ALG, et al. Chemically modified natural cotton fiber: A low–cost biosorbent for the removal of the Cu(II), Zn(II), Cd(II), and Pb(II) from natural water. Desalin. Water. Treat. 2013;52:4223–4233. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.804451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bojarczuk K, Kieliszewskarokicka B. Effect of ectomycorrhiza on Cu and Pb accumulation in leaves and roots of silver birch (betula pendula roth) seedlings grown in metal-contaminated soil. Water. Air. Soil. Pollut. 2010;207:227–240. doi: 10.1007/s11270-009-0131-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amarasinghe BMWPK, Williams RA. Tea waste as a low cost adsorbent for the removal of Cu and Pb from wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2007;132:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2007.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keskinkan O, et al. Heavy metal adsorption characteristics of a submerged aquatic plant (Myriophyllum spicatum) Process. Biochem. 2004;39:179–183. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00045-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Regmi P, et al. Removal of copper and cadmium from aqueous solution using switchgrass biochar produced via hydrothermal carbonization process. J. Environ. Manage. 2012;109:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hossain MA, et al. Palm oil fruit shells as biosorbent for copper removal from water and wastewater: experiments and sorption models. Bioresource. Technol. 2012;113:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Özer A, Özer D, Özer A. The adsorption of copper(II) ions on to dehydrated wheat bran (DWB): determination of the equilibrium and thermodynamic parameters. Process. Biochem. 2004;39:2183–2191. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2003.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim BS, et al. Removal of Cu2+ by biochars derived from green macroalgae. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016;23:985–994. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lezcano JM, et al. Biosorption of Cd(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) using different residual biomass. Chem. Ecol. 2010;26:1–17. doi: 10.1080/02757540903468102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Khare P, et al. Plant refuses driven biochar: application as metal adsorbent from acidic solutions. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:s3054–s3063. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.11.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Demiral H, Güngor C. Adsorption of copper (ii) from aqueous solutions on activated carbon prepared from grape bagasse. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;124:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Romerocano LA, Gonzalezgutierrez LV, Baldenegroperez LA. Biosorbents prepared from orange peels using Instant Controlled Pressure Drop for Cu(II) and phenol removal. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016;84:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bohli T, et al. Evaluation of an activated carbon from olive stones used as an adsorbent for heavy metal removal from aqueous phases. C. R. Chim. 2015;18(1):88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2014.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data has been deposited in figshare and are available at 10.6084/m9.figshare.8320700.