Abstract

Rotaviruses cause severe diarrhea in infants and young children, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Despite implementation of current rotavirus vaccines, severe diarrhea caused by rotaviruses still claims ~200,000 lives of children with great economic loss worldwide each year. Thus, new prevention strategies with high efficacy are highly demanded. Recently, we have developed a polyvalent protein nanoparticle derived from norovirus VP1, the S particle, and applied it to display rotavirus neutralizing antigen VP8* as a vaccine candidate (S-VP8*) against rotavirus, which showed promise as a vaccine based on mouse immunization and in vitro neutralization studies. Here we further evaluated this S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine in a mouse rotavirus challenge model. S-VP8* vaccines containing the murine rotavirus (EDIM strain) VP8* antigens (S-mVP8*) were constructed and immunized mice, resulting in high titers of anti-EDIM VP8* IgG. The S-mVP8* nanoparticle vaccine protected immunized mice against challenge of the homologous murine EDIM rotavirus at a high efficacy of 97% based on virus shedding reduction in stools compared with unimmunized controls. Our study further supports the polyvalent S-VP8* nanoparticles as a promising vaccine candidate against rotavirus and warrants further development.

Keywords: nanoparticle, vaccine platform, S particle, subunit vaccine, rotavirus, norovirus, subviral particle

INTRODUCTION

Rotaviruses, members of the family Reoviridae, cause severe diarrhea in infants and young children, resulting in dehydration of patients with significant morbidity, mortality, and economic loss [1]. Although several vaccines against rotaviruses have been approved for commercial use in many countries, rotavirus-caused severe diarrhea still leads to ~200,000 deaths, 2.3 million hospitalizations, and 24 million outpatient visits among infants and children younger than 5 years of age globally each year [2-4]. Therefore, new control and prevention strategies against this deadly human pathogen at higher efficacy than the current vaccines are urgently needed.

The two mostly implemented rotavirus vaccines, RotaTeq® (Merck) and Rotarix® (GlaxoSmithKline, GSK), are live attenuated virus vaccines. While they have been shown highly effective in protecting children against severe diarrhea caused by rotavirus infections in developed countries [5, 6], they did not show the same efficacies in many developing countries in Africa and Asia [7-9], where most rotavirus infections, morbidity, and mortality occur and where rotavirus vaccines are mostly needed. In addition, these two live vaccines continue to be associated with an increased risk of intussusception [10-16]. Furthermore, the two vaccines remain costly for the low-income nations. These common limitations of the live rotavirus vaccines prevent their wider implementation in many developing countries and therefore, new vaccines with improved cost-effectiveness and safety are highly demanded.

We have recently developed a polyvalent protein nanoparticle, the norovirus S particle, that consist of 60 shell (S) domains of the norovirus capsid protein [17]. When produced in an E. coli expression system, modified norovirus S domains that naturally build the inner shells of norovirus capsids self-assemble into 60-valent S particles with exposed C-termini on the surface. The unique features of the S particle, including its self-formation nature, polyvalence, and the freely exposed C-terminus of each S domain, make the S particle an excellent platform to display foreign antigens for enhanced immunogenicity. We have proved the concept by generating a chimeric S-VP8* nanoparticle that contains 60 displayed rotavirus neutralizing antigen VP8*s on the surface of the self-assembled S particles [17]. A similar principle has also been used for making S-HA1 particles that display the HA1 antigens of the H7N9 influenza virus [18].

The surface spike proteins or VP4s are the P genotype determinants of rotaviruses. The distal VP8* heads of VP4 is responsible for interacting with rotavirus glycan receptors to initiate a host-specific infection. Therefore, the VP8* protein plays an important role in rotavirus antigenic types and is an excellent vaccine target against rotavirus infection [19]. Recent advancements on rotavirus-host interactions have provided new insights into rotavirus infection, host ranges, and epidemiology [20-24], strengthening our ability to develop P type-based rotavirus vaccines targeting the VP8* antigen. Since the recombinant protein-based S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine is non-replicating and immunization will be given parenterally, replication of live rotavirus in the intestine will not occur and therefore, intussusception may not happen. In addition, the E. coli expression system is known for its easy and low-cost production of recombinant protein and thus will greatly reduce the cost of our S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine.

Our previous study [17] showed that the S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine elicited significantly higher antibody responses in mice toward the displayed VP8* antigens compared with that induced by free VP8* antigens. The mouse sera after immunization with S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine strongly blocked attachment of rotavirus VP8* protein to its glycan ligands and neutralized rotavirus replication in culture cells [17]. To further evaluate the protective efficacy of the vaccine, we constructed new S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccines containing the VP8* antigens of murine rotavirus EDIM (epizootic diarrhea of infant mice) strain [25], referred as S-mVP8* vaccine, and assessed their immune responses and protective efficacy in mice against challenge with EDIM rotaviruses. The results indicated that the S-mVP8* nanoparticle vaccine protected immunized mice against EDIM rotavirus challenge at a high efficacy (97%) based on a reduction of viral shedding in the stools of S-mVP8* nanoparticle vaccine-immunized mice compared with unimmunized controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

The DNA constructs for expressions of the S-mVP8* vaccines were created using the previously made plasmids for expression of the SR69A-VP8* and SR69A/V57C/Q58C/S136C-VP8* proteins [17] as templates. These two pET-24b (Novagen)-based plasmids contain a DNA fragment encoding a modified shell (S) domain with the hinge of norovirus VA387 (GII.4, GenBank accession no. AY038600.3; residues 1 to 221) with either a single mutation (R69A) or four mutations (R69A, V57C, Q58C, and S136C) and a DNA fragment encoding the VP8* antigen of a human P[8] rotavirus BM14113, equivalent to the amino acid sequences from 64 to 231 of the VP8* protein of Wa strain (G1P[8], GenBank accession no. VPXRWA) [17]. A Hisx6 tag was added at the end of the VP8* antigen for purification purpose (Figure 2, A and D).

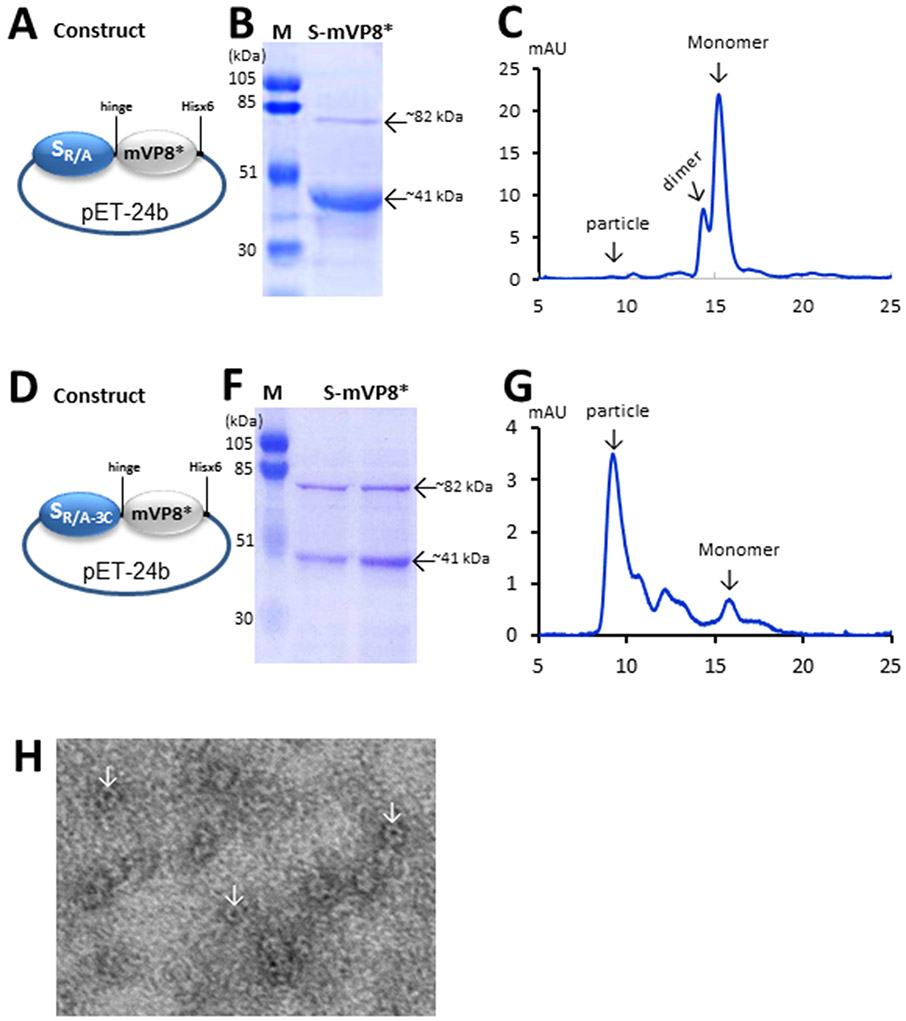

Figure 2.

Production and characterization of the S-mVP8* vaccines. (A to G) Schematic illustrations of the expression constructs (A and D), SDS-PAGE analyses (B and F), and elution curves of gel-filtration chromatography (C and G) of the SR/A-mVP8* (A to C) and SR/A-3C-mVP8* (D to G) proteins. In (A and D) SR/A represents the modified norovirus S domain with the R69A mutation, while SR/A-3C represents the modified norovirus S domain with the quadruple mutations of R69A, V57C, Q58C, and S136C. mVP8* represents the VP8* antigen of murine rotavirus. The hinge at the end of the S domain and the Hisx6 tag at the end of the mVP8* are indicated. In (B and F), the monomer (~41 kDa) and dimer (~82 kDa) of the S-mVP8* proteins are indicated, while lane M is the prestained protein markers with indicated molecular weights. In (C and G), elution curves of gel filtration chromatography of the two S-mVP8* vaccines through the size-exclusion column Superdex 200 (10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) are shown. The typical elution positions of the particle, dimer, and monomer of the S-VL8* proteins are indicated. (H) EM images of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* protein. Typical chimeric particles are shown by arrows.

To generate the two constructs (Figure 2, A and D) for production of the S-mVP8* vaccine, the human rotavirus VP8*-encoding fragments of the above two plasmids were replaced with DNA sequences encoding the VP8* antigen of a murine rotavirus EDIM strain (residues L65 to L222, GenBank accession no. AF039219) [25], respectively. This resulted in two vaccine constructs (Figure 2, A and D). One was a fusion of the murine rotavirus VP8* (mVP8*) to the S domain with a R69A mutation, referred as SR/A-mVP8*(Figure 2A), while a second construct was a fusion of the mVP8* to the S domain with quadruple mutations (R69A, V57C, Q58C, and S136C), referred as SR/A-3C-mVP8* (Figure 2D). The previous study [17] suggested that the two versions of the S-mVP8* proteins may differ in their particle formation and thus their immune responses. A DNA construct for production of a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged mVP8* protein was also made via the GST Gene Fusion System (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using the vector pGEX-4T-1 as described elsewhere [26-29].

Production of recombinant proteins.

The hisx6-tagged S-mVP8* vaccines were expressed in E. coli (BL21, DE3) and purified by TALON CellThru Resin (ClonTech) according to the instruction of the manufacturer as described previously [17, 30, 31]. The GST-tagged mVP8* protein that was also expressed in same E. coli strain was purified using resin of Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as described elsewhere [32-34].

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and protein quantitation.

Purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 10% separating gels and were quantitated by SDS-PAGE using serially diluted bovine serum albumin (BSA, Bio-Rad) with known concentrations as standards on same gels [25].

Gel filtration chromatography.

This was carried out as described elsewhere [33, 35, 36] through an AKTA Fast Performance Liquid Chromatography System (AKTA Pure 25L, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) via a size exclusion column (Superdex 200, 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to assess the size of the S-mVP8* vaccines and to further purify the GST-tagged mVP8* protein as the capture antigen for EIAs to determine the mVP8*-specific IgG titers. The column was calibrated using gel filtration calibration kits (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and the previously made norovirus P particles (~830 kDa) [36, 37], small P particles (~420 kDa) [38], and P dimers (~69 kDa) [35] as described previously [39].

Electron Microscopy.

The S-mVP8* proteins were inspected by electron microscopy (EM) for particle formation using 1% ammonium molybdate as the staining solution as described elsewhere [36]. Specimens were observed under an EM10 C2 microscope (Zeiss, Germany) at 80 kV at magnifications between 10,000× and 40,000×.

Immunization of mice.

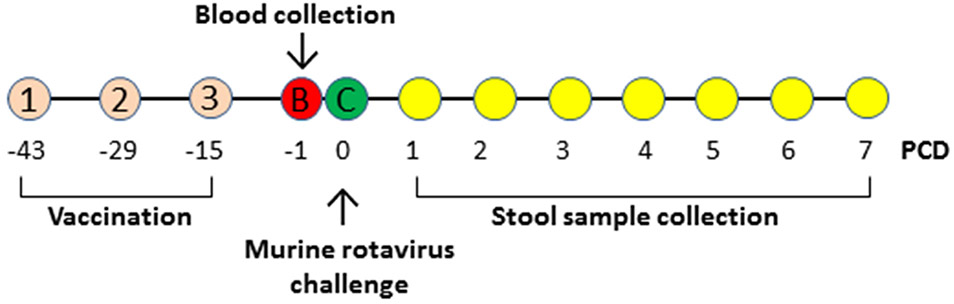

Rotavirus-specific-antibody-free BALB/c mice (Harlan-Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) at 3-4 weeks of age were randomly divided into four groups (n = 6) and each group was immunized with one of the following three immunogens or their diluent: 1) SR/A-3C-mVP8* nanoparticle vaccine in 5 μg/dose; 2) monomeric/dimeric SR/Ax-mVP8* vaccine in 15 μg/dose; 3) the S nanoparticles without mVP8* antigen in 15 μg/mouse/dose as a negative control, and 4) phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) that was the diluent of the above immunogens as a further negative control. These immunogens or PBS in same volumes (100 μL) were immunized to mice subcutaneously using Inject Alum adjuvant (Thermo Scientific, 50 μL/dose). 15 μg/dose was selected based on our previous study [25], while 5 μg/dose was selected due to the facts that the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine has low yields and that the particle vaccine can generally induce strong immune response [40]. Mice were immunized three times in 2-week intervals as described previously [25, 33]. Bloods were collected two weeks after the final immunization via tail vein before viral challenge (Figure 1). Sera were processed from blood via a standard protocol [25].

Figure 1.

Experimental design. Mice were immunized with various immunogens for three times indicated by (1), (2), and (3) in two week-intervals. Blood samples (B) were collected to determine immune responses. Immunized mice were then challenged (C) with EDIM rotavirus and stool samples were collected each day for seven days, from post challenge day (PCD) 1 to 7, to examine rotavirus shedding. All the experiments are outlined based on the time line of PCDs.

Murine rotavirus challenge and determination of virus shedding.

The established murine rotavirus challenge model [25, 41-43] was used to examine the protective efficacy of the S-mVP8* particle vaccine. Two weeks after the last immunization with the S-mVP8* vaccine or negative controls, mice were challenged by oral gavage with the murine rotavirus EDIM strain at a dose of 8 ×105 focus-forming units (FFU), which is equivalent to 2×106 50% shedding doses. Two fecal pellets were collected from each mouse each day for 7 days after EDIM challenge (Figure 1). The fecal pellets were kept in 1 ml of Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) and stored frozen. At the time of analysis, fecal pellets were homogenized and centrifuged to remove debris. Rotavirus antigen in the fecal samples (ng/ml) were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously [43]. To this end, a standard curve was generated using purified EDIM double-layer particles with known rotavirus antigen concentration (180 μg/ml). The purified EDIM particles were diluted starting from 37.5 to 4800 to ng/ml. The clarified stool samples were diluted 20 folds to produce OD readings in the range of the standard curve. The stool samples with OD<0.1, which represent an undetectable value of rotavirus antigen by the ELISA were arbitrarily set to a low value of 20 ng/ml that was considered a negative value.

Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs).

EIA assays were performed to determine the rotavirus VP8*-specific IgG titers in the mouse sera after immunization as described previously [25] using the gel-filtration-purified GST-mVP8* protein as capture antigen. The GST-mVP8* antigen at 1 μg/ml was used to coat 96-well microtiter plates and then incubated with serially diluted mouse sera. Bound antibodies were measured by incubations with goat-anti-mouse IgG HRP (horseradish peroxidase) conjugated (MP Biomedicals, Inc). The anti-mVP8* IgG titers were defined as an end-point dilution with a cutoff signal of OD450=0.15. Sera samples that did not produce an OD>0.15 at 1:20 dilution were arbitrarily given a value of 10.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences among data sets were assessed by software GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc) using an unpaired t test. P-values were set at 0.05 (P < 0.05) for significant difference, 0.01 (P<0.01) for highly significant difference, and 0.001 or 0.0001 (P<0.001/P<0.0001) for extremely significant difference.

Ethics statement.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (23a) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation (Animal Welfare Assurance no. A3108-01).

RESULTS

Production of two S-mVP8* vaccines.

Two S-mVP8* vaccines were made in this study, the SR/A-mVP8* vaccine was a fusion of the murine rotavirus VP8* (mVP8*) to the S domain with a R69A mutation, while the SR/A-3c-mVP8* vaccine was a fusion of the mVP8* to the S domain with quadruple mutations (R69A, V57C, Q58C, and S136C) (Figure 2, A and D). Both fusion proteins were produced as soluble proteins in the E. coli system, but the yield of the SR/A-mVP8* vaccine (~2 mg/liter bacteria culture) was higher than that of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* vaccine (~0.8w (Figure 2, compared B and F).

As found previously [17], SDS PAGE analyses of the two vaccines revealed both monomer (~41 kDa) and dimer (~82 kDa) forms. Higher ratio of dimeric proteins was seen in the SR/A-3C-mVP8* construct than that of the SR/A-mVP8* construct, which is consistent with the higher inter-S domain interaction of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* proteins due to the introduction of the inter-S domain disulfide bonds. Accordingly, gel-filtration chromatography of the two proteins showed that the SR/A-mVP8* protein was a mixture of monomers and dimers without assembling into nanoparticles (Figure 2C) based on their typical elution positions [17]. By contrast, majority of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* protein appeared to form nanoparticles (Figure 2G), which was supported by the observed particle formation via electron microscopy (Figure 2H). Therefore, the SR/A-3C-mVP8* protein was a nanoparticle vaccine, while the SR/A-mVP8* protein was a monomer/dimer vaccine.

Immune responses of the S-mVP8* vaccines in mice.

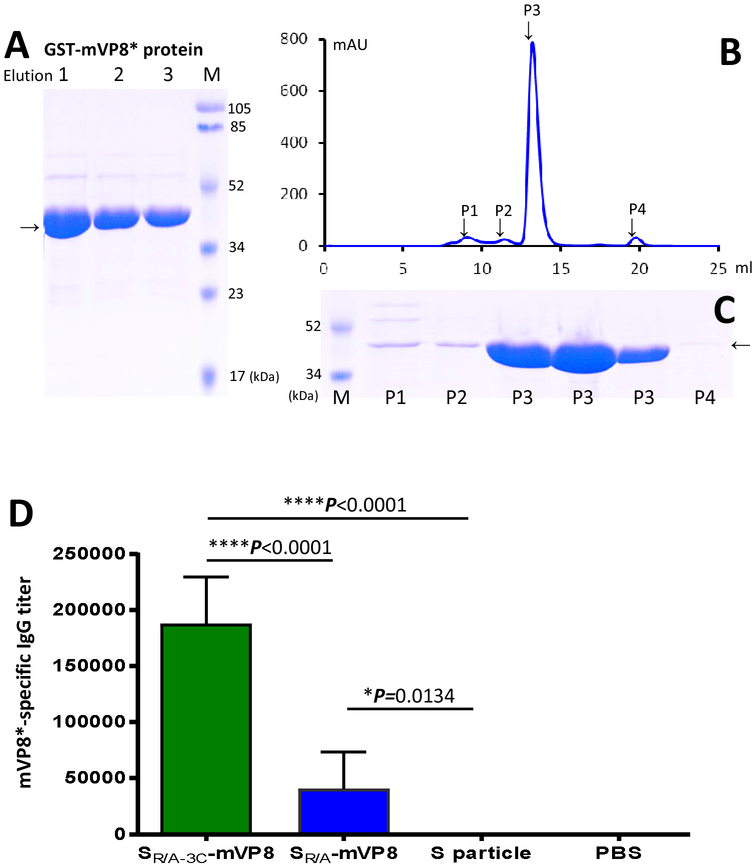

The SR/A-mVP8* and SR/A-3C-mVP8* vaccines were used to immunize mice along with previously made S nanoparticles [17] and vaccine diluent (PBS) as negative controls. After three immunizations, mVP8*-specific IgG responses of the immunized mice were evaluated. To this end, GST-mVP8* protein was produced and further purified via gel-filtration chromatograph to reach a purity nearly 100% (Figure 3, A to C, lanes P3) to be used as capture antigens in EIA assays. Our results showed that, while both S-mVP8* vaccines elicited antibody responses, the mVP8*-specific IgG titer elicited by the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine was ~4.6 folds higher than that elicited by the monomeric/dimeric SR/A-mVP8* vaccine and this difference was statistically extremely significant (P<0.0001, Figure 3D). As negative controls, the S particle without mVP8* antigen and PBS did not elicit any detectable mVP8*-specific IgG response.

Figure 3.

Immune responses of the S-mVP8* vaccines in mice. (A to C) production and purification of GST-mVP8* protein as capture antigens for EIA to assess the mVP8*-specific IgG titers. (A) Three affinity column-eluted fractions (1 to 3) of the GST-mVP8* proteins were analyzed on an SDS PAGE gel. (B and C) The GST-mVP8* protein was further purified by gel-filtration chromatography (B) and the four observed peaks (P1, P2, P3, and P4) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (C), in which three eluted fractions from P3 were loaded. Lanes M are prestained protein markers with indicated molecular weights. Arrows indicate the GST-mVP8* proteins. (D) Both S-mVP8* vaccines elicited mVP8*-specific IgG responses, in which the SR/A-3C-VP8* particle vaccine elicited significantly higher mVP8*-specific IgG titer than that elicited by the SR/A-VP8* monomeric/dimeric vaccine. As negative controls the S particle without the mVP8* antigen and PBS did not induce such immune response. Data are shown by columns (mean values) with error bars (standard deviations). The statistical differences between the data groups are shown by star symbols with indicated P values (* P <0.05, **** P<0.001).

Virus shedding of vaccinated mice after EDIM challenge.

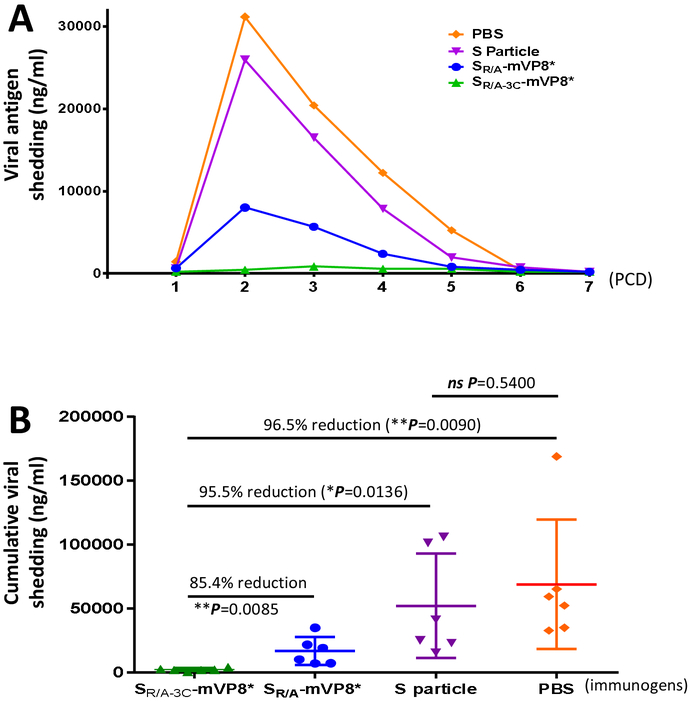

The vaccinated mice were challenged with EDIM rotavirus and virus shedding was determined for seven days, from post challenge day (PCD) 1 to 7 (Figure 4A). The results showed that after EDIM challenge the control mice that were immunized with the S particle or PBS without mVP8* antigens shed viral antigens in large amounts, reaching a maximum shedding on PCD 2 over 26000 ng/ml of detectable viral antigen. Shedding was resolved and reached undetectable levels on PCD 6 or 7. Most viral shedding occurred from PCD 2 to 5. In contrast, both S-mVP8* vaccines reduced virus shedding dramatically with a peak virus shedding at 8000 ng/ml on PCD 2 for the SR/A-mVP8* vaccine group and only 0.85 μg/ml on PCD 3 for the SR/A-3C-mVP8* vaccine group (Figure 4A), indicating the significantly reduced shedding after immunization with the two S-mVP8* vaccines.

Figure 4.

Shedding of viral antigen of vaccinated mice after EDIM challenge. (A) Viral antigen shedding in immunized mice during the first 7 days (post challenge day, PCD, 1 to 7) after virus challenge. Each data point is a mean value of rotavirus shedding in the different groups of mice of the indicated experimental groups (n=6). (B) The cumulative amount of viral antigen shedding of mice in the different experimental groups. Each data point is a cumulative value of viral antigen shedding for each mouse from PCD 2 to PCD 5. The lines in the middle represent the mean value of the group, while the bars indicate the standard deviation. The percentage of shedding between the SR/A-3C-mVP8* vaccine group and other controls, as well as their corresponding statistic P values are shown.

Protective efficacy of the S-mVP8* particle vaccines.

We then calculated and compared the cumulative virus shedding of individual mice in each experimental group during the peak shedding period (PCD 2 to 5) (Figure 4B). The results showed that the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine group revealed the most reduced shedding, exhibiting 97% and 96% reduction compared with the S particle (P=0.0136) and PBS (P=0.009) control groups, respectively (Figure 4B). The SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine also showed 85% reduction compared with the SR/A-mVP8* group (P=0.0085). By contrast, the difference between the two control groups was not significant (P=0.5400). These data indicated a high (96-97%) efficacy of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine in protecting immunized mice against murine rotavirus shedding.

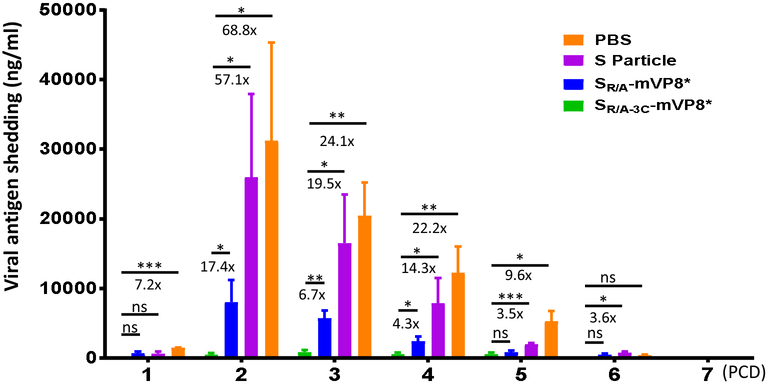

Daily virus shedding reductions caused by the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine.

Finally, we calculated the daily virus shedding reductions caused by the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine during the virus shedding period after virus challenge compared with other control groups (Figure 5). The data showed that such virus shedding reductions were correlated positively with the corresponding virus shedding levels of the negative controls. For example, compared with the PBS control group, the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine caused smaller virus shedding reduction (7.2 folds) on PCD 1, but reached the largest reduction on PCD 2 (68.8 folds). Then the shedding reduction went down along with the decrease of virus shedding in the PBS control group. Similar scenarios were also seen when compared with the other negative control (S particle) or the monomeric/dimeric SR/A-mVP8* vaccine groups (Figure 5). These data further supported the notion that SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine protects immunized mice against murine rotavirus infection at high efficacy.

Figure 5.

Reduction of viral antigen shedding in the SR/A-3C-mVP8* immunized mice after EDIM challenge. The daily viral antigen shedding in each experimental group are shown in columns (means) with error bars (standard error of means, SEM) in variable colors. The reduction in shedding in the SR/A-3C-mVP8* immunized mice and their statistic significances compared with each of the remaining three groups are shown, in which * means P < 0.05, ** means P < 0.01, and *** means P<0.001.

DISCUSSION

The norovirus S particle, a 60 valent protein nanoparticle, was developed previously and we demonstrated that human rotavirus VP8* antigens can be displayed by the S particles, forming chimeric S-VP8* nanoparticles [17]. Further study showed that the polyvalent S-VP8* nanoparticles elicited enhanced immune responses in mice toward the displayed VP8* antigens compared with those induced by the free VP8* antigens [17]. The mouse sera after immunization with the S-VP8* particles strongly blocked the attachment of rotavirus VP8* protein to its glycan ligands and significantly reduced rotavirus replication in cell culture [17]. In this study, we provide new evidence to show that the S-mVP8* nanoparticle is a useful vaccine candidate that protected vaccinated mice against homologous murine rotavirus challenge at high reduction of viral shedding of 97% compared to negative control mice. These new data further support the notion that the S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine is a promising approach against rotavirus illness and thus warrants further development for prevention of human rotavirus disease and epidemics.

During this study we noted both difference and similarity of the VP8* antigens between human (a Wa-like P[8] strain) and murine (EDIM strain) rotaviruses in terms of S-VP8* nanoparticle formation. The two VP8* antigens share only 57% amino acid identity and this low homology implies their difference in protein property. Indeed, unlike the SR/A-VP8* fusion protein containing the human rotavirus VP8* antigens that formed chimeric particle at an efficiency of ~50% [17], the SR/A-mVP8* fusion protein that contains the murine rotavirus VP8* antigens did not form particles, but forming dimers and monomers. As was observed previously [17], introduction of the inter-S domain disulfide bonds through the quadruple mutations of R69A, V57C, Q58C, and S136C enhanced the particle formation of SR/A-3C-mVP8* dramatically.

Another difference was the production yield of the soluble S-mVP8* protein containing the murine rotavirus VP8* antigens (0.8-2.0 mg/liter bacteria culture) that was significantly lower than those (up to 40 mg/liter bacteria culture) of the S-VP8* protein containing the human rotavirus VP8* antigen [17]. We also noted that production yield of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine (~0.8 mg/liter bacteria culture) was clearly lower than that of the SR/A-mVP8* vaccine (~2.0 mg/L bacteria culture), a scenario that was also observed in our previous study when compared the production yield of the S-VP8* proteins without the inter-S domain disulfide bonds with those with the inter-S domain disulfide bonds [17]. The low yield of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* vaccine was the reason for its lower dose (5 μg/dose) that was used to immunize mice compared with that of the SR/A-mVP8* vaccine (15 μg/dose).

This study also provided additional evidence to support the notion that the polyvalent nanoparticle formation of the S-VP8* vaccines is a critical factor to elicit improved immune responses [17]. For example, the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine elicited significantly higher titer of mVP8*-specific IgG compared with that elicited by the monomeric/dimeric SR/A-mVP8* proteins, even though less dose of the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine (5 μg/dose) than that of the SR/A-mVP8* proteins (15 μg/dose) was used. Accordingly, our study further showed that the SR/A-3C-mVP8* particle vaccine protected the immunized mice at a significantly higher efficacy than that provided by the monomeric and dimeric SR/A-mVP8* proteins, indicating the importance of the polyvalent nanoparticle formation in the S-VP8* vaccines.

This project was based on our previous study showing that the S-VP8* nanoparticles induced strong immune responses in mice and the resulted mouse sera exhibited strong neutralization activity against human rotavirus (Wa, G1P[8]) replication in culture cells [17]. Thus, this study focused on the determination of the protective efficacy of the S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine as further evidence to warrant the future development of the vaccine. For this reason, we did not assess the neutralization of the vaccine because this has been studied thoroughly previously [17], which showed that the levels of the RV VP8*-specific IgG titers are well correlated with the level of neutralizing activity.

Finally, the question on whether the S-VP8* vaccine may offer protection against norovirus remains elusive. The S-VP8* nanoparticle vaccine contains the S domain of norovirus VP1 that naturally forms the interior, icosahedral shell of norovirus capsid [44]. Norovirus protrusions that are formed by the P domains are known to interact with the host attachment factors or receptors to initiate viral infections and therefore the P domain is an important norovirus neutralizing antigen and an ideal vaccine target. On the other hand, the interior shell builds the icosahedral structure of the virus and its role in norovirus infection and replication cycle remains unknown, due to the lack of an effective cell culture or a small animal model for norovirus to test whether the S particle offers protection against norovirus infection and replication. Thus, this issue need to be clarified by future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Monica M. McNeal at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center for providing EDIM rotavirus and reagents for detection of EDIM antigens in mouse stool samples. The research described in this article was supported by the National Institute of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (5R01 AI089634-01 to X.J. and R21 AI092434-01A1 to M.T.) and an institutional Innovation Fund of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center to M.T.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Glass RI, Bresee J, Jiang B, Gentsch J, Ando T, Fankhauser R, et al. Gastroenteritis viruses: an overview. Novartis Found Symp 2001;238:5–19; discussion −25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD, et al. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, Glass RI. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:304–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013;381:1405–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vesikari T, Itzler R, Matson DO, Santosham M, Christie CD, Coia M, et al. Efficacy of a pentavalent rotavirus vaccine in reducing rotavirus-associated health care utilization across three regions (11 countries). Int J Infect Dis 2007;11 Suppl 2:S29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yen C, Tate JE, Patel MM, Cortese MM, Lopman B, Fleming J, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: update on global impact and future priorities. Human vaccines 2011;7:1282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zaman K, Dang DA, Victor JC, Shin S, Yunus M, Dallas MJ, et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in Asia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D, Witte D, Kirsten M, Louw C, et al. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med 2010;362:289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Armah GE, Sow SO, Breiman RF, Dallas MJ, Tapia MD, Feikin DR, et al. Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Desai R, Cortese MM, Meltzer MI, Shankar M, Tate JE, Yen C, et al. Potential intussusception risk versus benefits of rotavirus vaccination in the United States. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2013;32:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bauchau V, Van Holle L, Mahaux O, Holl K, Sugiyama K, Buyse H. Post-marketing monitoring of intussusception after rotavirus vaccination in Japan. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 2015;24:765–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yung C-F, Chan SP, Soh S, Tan A, Thoon KC. Intussusception and Monovalent Rotavirus Vaccination in Singapore: Self-Controlled Case Series and Risk-Benefit Study. The Journal of pediatrics 2015;167:163–8.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rosillon D, Buyse H, Friedland LR, Ng S-P, Velazquez FR, Breuer T. Risk of Intussusception After Rotavirus Vaccination: Meta-analysis of Postlicensure Studies. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2015;34:763–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yih WK, Lieu TA, Kulldorff M, Martin D, McMahill-Walraven CN, Platt R, et al. Intussusception risk after rotavirus vaccination in U.S. infants. N Engl J Med 2014;370:503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Weintraub ES, Baggs J, Duffy J, Vellozzi C, Belongia EA, Irving S, et al. Risk of intussusception after monovalent rotavirus vaccination. N Engl J Med 2014;370:513–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Glass RI, Parashar UD. Rotavirus vaccines--balancing intussusception risks and health benefits. N Engl J Med 2014;370:568–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xia M, Huang P, Sun C, Han L, Vago FS, Li K, et al. Bioengineered Norovirus S60 Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Vaccine Platform. ACS Nano 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tan M, Cui LB, Huo X, Xia M, Shi FJ, Zeng XY, et al. Saliva as a source of reagent to study human susceptibility to avian influenza H7N9 virus infection. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tan M, Xia M, Huang P, Wang L, Zhong W, McNeal M, et al. Norovirus P Particle as a Platform for Antigen Presentation. Procedia in Vaccinology 2011;4:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Van Trang N, Vu HT, Le NT, Huang P, Jiang X, Anh DD. Association between norovirus and rotavirus infection and histo-blood group antigen types in Vietnamese children. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:1366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tan M, Jiang X. Histo-blood group antigens: a common niche for norovirus and rotavirus. Expert reviews in molecular medicine 2014;16:e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nordgren J, Sharma S, Bucardo F, Nasir W, Gunaydin G, Ouermi D, et al. Both Lewis and secretor status mediate susceptibility to rotavirus infections in a rotavirus genotype-dependent manner. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:1567–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Imbert-Marcille B-M, Barbe L, Dupe M, Le Moullac-Vaidye B, Besse B, Peltier C, et al. A FUT2 gene common polymorphism determines resistance to rotavirus A of the P[8] genotype. J Infect Dis 2014;209:1227–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hu L, Crawford SE, Czako R, Cortes-Penfield NW, Smith DF, Le Pendu J, et al. Cell attachment protein VP8* of a human rotavirus specifically interacts with A-type histo-blood group antigen. Nature 2012;485:256–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tan M, Huang P, Xia M, Fang PA, Zhong W, McNeal M, et al. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J virol 2011;85:753–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu Y, Huang P, Tan M, Liu Y, Biesiada J, Meller J, et al. Rotavirus VP8*: phylogeny, host range, and interaction with histo-blood group antigens. J virol 2012;86:9899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu Y, Ramelot TA, Huang P, Liu Y, Li Z, Feizi T, et al. Glycan Specificity of P[19] Rotavirus and Comparison with Those of Related P Genotypes. J virol 2016;90:9983–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liu Y, Xu S, Woodruff AL, Xia M, Tan M, Kennedy MA, et al. Structural basis of glycan specificity of P[19] VP8*: Implications for rotavirus zoonosis and evolution. PLoS Pathog 2017;13:e1006707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huang P, Xia M, Tan M, Zhong W, Wei C, Wang L, et al. Spike protein VP8* of human rotavirus recognizes histo-blood group antigens in a type-specific manner. J virol 2012;86:4833–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xia M, Wei C, Wang L, Cao D, Meng XJ, Jiang X, et al. A trivalent vaccine candidate against hepatitis E virus, norovirus, and astrovirus. Vaccine 2016;34:905–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xia M, Wei C, Wang L, Cao D, Meng XJ, Jiang X, et al. Development and evaluation of two subunit vaccine candidates containing antigens of hepatitis E virus, rotavirus, and astrovirus. Sci Rep 2016;6:25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang L, Cao D, Wei C, Meng XJ, Jiang X, Tan M. A dual vaccine candidate against norovirus and hepatitis E virus. Vaccine 2014;32:445–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang L, Huang P, Fang H, Xia M, Zhong W, McNeal MM, et al. Polyvalent complexe s for vaccine development. Biomaterials 2013;34:4480–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang L, Xia M, Huang P, Fang H, Cao D, Meng XJ, et al. Branched-linear and agglomerate protein polymers as vaccine platforms. Biomaterials 2014;35:8427–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J virol 2004;78:6233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol 2005;79:14017–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tan M, Fang P, Chachiyo T, Xia M, Huang P, Fang Z, et al. Noroviral P particle: structure, function and applications in virus-host interaction. Virology 2008;382:115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tan M, Fang PA, Xia M, Chachiyo T, Jiang W, Jiang X. Terminal modifications of norovirus P domain resulted in a new type of subviral particles, the small P particles. Virology 2011;410:345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Xia M, Huang P, Sun C, Han L, Vago FS, Li K, et al. Bioengineered Norovirus S60 Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Vaccine Platform. ACS Nano 2018;12:10665–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Xia M, Tan M, Wei C, Zhong W, Wang L, McNeal M, et al. A candidate dual vaccine against influenza and noroviruses. Vaccine 2011;29:7670–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Choi AH, Basu M, McNeal MM, Flint J, VanCott JL, Clements JD, et al. Functional mapping of protective domains and epitopes in the rotavirus VP6 protein. J Virol 2000;74:11574–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Choi AH, McNeal MM, Basu M, Bean JA, VanCott JL, Clements JD, et al. Functional mapping of protective epitopes within the rotavirus VP6 protein in mice belonging to different haplotypes. Vaccine 2003;21:761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].McNeal MM, Rae MN, Bean JA, Ward RL. Antibody-dependent and -independent protection following intranasal immunization of mice with rotavirus particles. J Virol 1999;73:7565–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann MG, Estes MK. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science 1999;286:287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]