Abstract

Background

Medical diagnoses and assessed need for care are the prerequisites for planning and delivery of care to residents of care homes. Assessing the effectiveness of care is difficult. The aim of this study was to test the practicality and construct validity of the howRu health status measure using secondary analysis of a large data set.

Method

The data came from a Bupa Care Homes Census in 2012, which covered 24 506 residents in 395 homes internationally (UK, Australia and New Zealand). Staff completed optical mark readable forms about each resident using a short generic health status measure, howRu. Response rates were used to assess practicality and expected relationships between health status and independent variables were used to assess the construct validity.

Results and discussion

19,438 forms were returned (79.3%) in 360 care homes (91.1%); complete health status data were recorded for 18 617 residents (95.8% of those returned). Missing values for any health status items mostly came from a small number of homes. The relationships between howRu and independent variables support construct validity. Factor analysis suggests three latent variables (discomfort, distress and disability/dependence).

Conclusions

HowRu proved easy to use and practical at scale. The howRu health status measure shows good construct validity.

Keywords: healthcare quality improvement, nursing homes, quality measurement, surveys

Background

The health status of care home residents is a key parameter for all concerned in care homes. A simple way to track health status routinely at both the individual and collectively at care home level is necessary to understand and optimise care and support decision-making.

The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment remains the key starting point but is not suitable for frequent repeated use.1 Cognitive impairment, such as dementia, is common in care homes and many residents are not able to rate their own health status. For this reason, proxy ratings by staff are needed.

Between 2003 and 2012, Bupa Care Services undertook a series of censuses of their care home residents.2 The June 2012 census provided an opportunity to record resident health status using the short generic staff-reported health status measure, howRu.3 While Bupa had undertaken a series of resident surveys serially that had included diagnosis and physical and mental capacity, it had not been able to assess health status. The census covered 24 506 residents in 395 care homes in UK, Australia and New Zealand. The primary purpose of the census was to inform strategic development.

Since 2012, Bupa’s Aged Care provision has changed significantly. The number of care homes in the UK has fallen from 303 to 138 and in Australia and New Zealand has increased from 92 to 121. In 2019, Bupa cares for about 17 000 care home residents in these countries.4 The data reported here do not represent care homes currently operated by Bupa.

This paper has used secondary analysis to better understand the practicality of the method used to record health status and the construct validity of the measure used, when collected by staff. Other studies have reported the use of staff proxies to record resident health status,5 6 but this study is a lot larger.

Method

HowRu

The howRu measure was chosen to measure health status, because it is short, quick and easy use and had been validated for use by older patients.7 It was also being used in other Bupa projects at the time. HowRu is a short generic health status measure, which covers how the subject is feeling physically and emotionally, and how much they can do for themselves.

HowRu was developed as a generic patient-reported outcome measure (PROM), suitable for most types of patient irrespective of diagnosis and treatment and across different care settings: secondary, primary, community, social and home care. HowRu has been validated for use with patients with long-term conditions living in the community against the SF-12 survey tool,7 in hospital clinics8 and for hip and knee replacement surgery against EQ-5D-3L,9 and at the individual patient level.10 This is the first report of its use in care homes by staff proxies.

HowRu uses the question “How are you today?” referring to the past 24 hours. In this study, the question was adapted to “How is the resident today?”.

It has four items:

Pain or discomfort covers physical symptoms.

Feel low or worried relates to emotional symptoms.

Limited in what he/she can do covers disability, activities of daily living and leisure activities.

Require help from others covers self-care and dependency.

Each option is indicated in the following mutually supporting ways to minimise cognitive effort, for face validity and to reduce training needs:

Written labels: none, a little, quite a lot and extreme.

Colour: green, yellow, orange and red.

Emoji: face pictographs from happy to miserable.

Position: increasing in severity from left to right.

The combination of four items and four options each creates a 4×4 matrix with 256 (44) possible combinations. Each option is allocated a score on a 0 to 3 ordinal scale (extreme=0, quite a lot=1, a little=2 and none=3). The howRu summary score for each subject is calculated by adding the item scores, giving a range from the floor, 0 (4×extreme), to the ceiling, 12 (4×none). A high score is always good, and a low score is bad.

For reporting mean scores for a group of respondents, the average score is converted to a scale with range 0 to 100. A score of zero is obtained when all responses are at the floor (extreme) and 100 when all responses are at the ceiling (none). This scale is familiar to most people, allows comparison of item and summary scores on the same scale, and distinguishes mean scores from individual data collection.

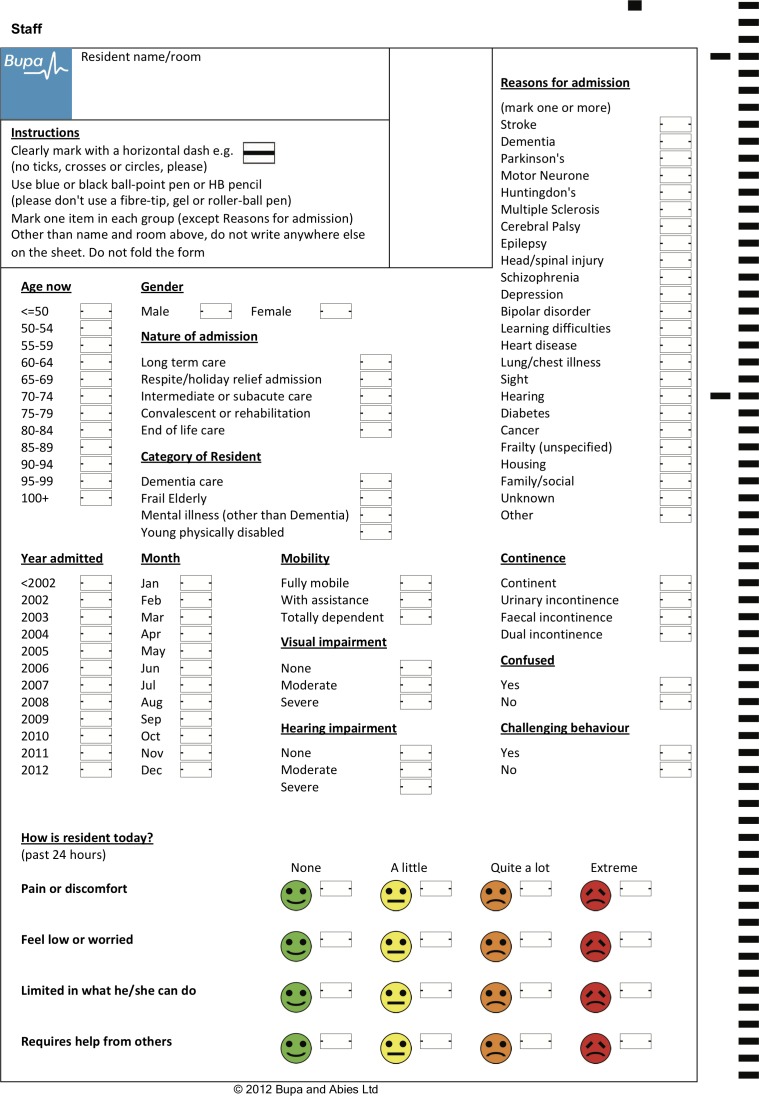

Respondents recorded data on optical mark readable (OMR) forms with sections for staff and residents to complete (this paper only considers staff responses). A bar code identified the care home and region. The staff form (see figure 1) included questions asked in previous censuses, allowing changes in the population over time to be explored.11 In addition, staff rated each resident’s health status, using howRu, shown at the bottom of the form. Responses for each region were collated regionally and forwarded to a central scanning bureau for data entry. The data were imported into a database and exported to Excel and the JASP statistical package for analysis.

Figure 1.

Staff data collection form (A4).

Construct validation

Construct validation explores how a measure relates to existing theories. It provides information about how scores can be interpreted and used. Construct validation involves setting out theoretical concepts, how they relate to each other and the dimensions of the measure, and then testing the relationships between these constructs and the results obtained.12

We tested the following hypotheses:

Health status, age and sex. We did not expect any difference between sexes but expected that older people would have lower health status in terms of disability and dependence.

Health status and length of stay in the care home. We expected that health status would generally diminish with length of stay, as people got older and frailer.

Health status, admission type, resident category, number of reasons for admission and case mix. We expected to find differences in health status between different categories of resident.

Health status, mobility, visual and hearing impairment, continence, confusion and challenging behaviour. We expected health status to be negatively associated with impairment.

Health status and whether residents could complete the survey themselves. We expected a strong positive association.

Psychometric analysis

The inter-relatedness of the howRu items was assessed by examining correlations, Cronbach’s α and exploratory factor analysis, orthogonal rotation(varimax).12 13

Ethics statement

We carried out secondary analysis of data collected as part of a routine census of care home residents. The data were anonymous and undertaken to evaluate the current services without randomisation, so ethics approval was not required. No data were collected about identifiable residents, and there was no risk to individual residents.14

Patient and public involvement

There was no direct involvement of patients or the public. All data were anonymous.

Results

Response rates

In June 2012, centrally collected management statistics showed that the 395 care homes had 24 506 residents. Thirty-five care homes did not return any completed forms or only returned forms for less than 3% of its residents, giving a home response rate of 91.1% (360/395).

Staff completed and returned 19 438 responses, an overall completion rate of 79.3% (table 1). Any form that was returned but did not, at a minimum, contain resident gender was not treated as completed.

Table 1.

Number of care homes, occupancy and completed forms by country

| Region | Care homes | Homes with >3% returned | Home response (%) |

Number of occupants | Number of completed returns | Individual response rate (%) |

| UK | 303 | 273 | 90% | 17 913 | 13 152 | 73% |

| Australia | 48 | 44 | 92% | 3666 | 3462 | 94% |

| New Zealand | 44 | 43 | 98% | 2927 | 2824 | 95% |

| Total | 395 | 360 | 91% | 24 506 | 19 438 | 79% |

The number of responses and missing values for each howRu item are shown below (table 2). Missing values for one or more howRu items were found in 821 resident forms (4.2%). A very small number of respondents (less than 0.3%) made two responses for items that required only one response. Such entries were treated as null.

Table 2.

Responses and missing values completing staff howRu form

| Item | Responses | Missing values | % |

| Pain or discomfort | 18 931 | 507 | 2.6 |

| Feeling low or worried | 18 838 | 600 | 3.1 |

| Limited in what he/she can do | 18 864 | 574 | 3.0 |

| Require help from others | 18 915 | 523 | 2.7 |

| All howRu items | 18 617 | 821 | 4.2 |

More than a third (34%) of all missing values were from just 13 care homes (3.5%). This suggests that two different types of error are taking place. For a few residents (probably no more than 1%), staff found it hard to make the right choice, but in a few care homes, missing values are due to local circumstances or processes, such as staff training, management or simple human error. For example, one member of staff might complete basic data for all residents in a home, but expect someone else, who knew individual residents better, to complete the remainder of the form, which was not done.

Overall distribution

The overall frequency distribution of individual howRu items rated by staff on residents is shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Overall distribution of staff ratings of resident health status

| None | A little | Quite a lot | Extreme | Total | |

| Pain or discomfort | 10 741 (57%) | 6507 (34%) | 1508 (8%) | 175 (1%) | 18 931 |

| Feeling low or worried | 9523 (51%) | 6880 (37%) | 2086 (11%) | 349 (2%) | 18 838 |

| Limited in what he/she can do | 1989 (11%) | 5462 (29%) | 6676 (35%) | 4737 (25%) | 18 864 |

| Requires help from others | 1111 (6%) | 4880 (26%) | 6877 (36%) | 6047 (32%) | 18 915 |

This distribution differs substantially with that of people with long-term conditions, who are living in their own homes,7 although that study was based on reporting by patients themselves, not staff as proxies.

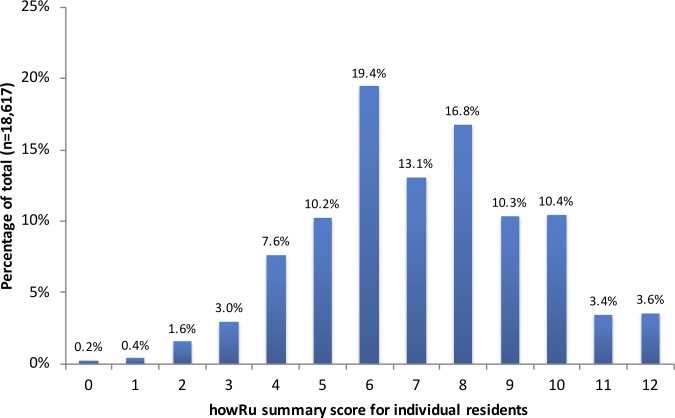

The howRu score is an aggregate of the four items, with a range from 0 to 12. The mean staff-rated howRu score for care home residents is 7.14 (SD 2.31). Figure 2(figure 2) shows the broad distribution of scores, showing a broadly normal distribution. The number of residents rated at the ceiling state (4×none) is 666 (3.6%); the number at the floor state (4×extreme) is 46 (0.2%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of staff-reported howRu summary scores for care home residents (n=18 617).

Independent variables

This section examines the relationship between howRu data and independent variables including resident gender, age, length of stay (year of admission), admission type, resident category, number of reasons for admission, mobility, visual impairment, hearing impairment, continence, confusion and challenging behaviour, and the ability of residents to complete the howRu questionnaire. The distribution of responses and mean scores for each howRu item and summary score are shown in table 4. This shows results where all howRu items were completed. Where numbers do not add to the overall total, this indicates missing values.

Table 4.

Mean scores for each item and summary score on 0–100 scale by independent variable

| Independent variable | N (%) | Mean Discomfort Score |

Mean Distress Score |

Mean Disability Score |

Mean Dependence Score |

Mean howRu Score |

| With complete howRu data | 18 617 | 82.3 | 78.6 | 41.7 | 35.3 | 59.5 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 12 380 (67%) | 81.7 | 77.7 | 41.3 | 35.0 | 58.9 |

| Male | 6033 (33%) | 83.6 | 80.4 | 42.5 | 36.0 | 60.6 |

| Age | ||||||

| <50 | 196 (1%) | 81.6 | 79.8 | 33.7 | 27.4 | 55.6 |

| 50–54 | 152 (1%) | 83.3 | 81.4 | 39.0 | 34.4 | 59.5 |

| 55–59 | 302 (2%) | 85.4 | 81.1 | 42.2 | 37.3 | 61.5 |

| 60–64 | 436 (2%) | 85.9 | 80.3 | 44.3 | 36.8 | 61.8 |

| 65–69 | 745 (4%) | 83.0 | 79.9 | 40.6 | 35.2 | 59.7 |

| 70–74 | 1222 (7%) | 82.6 | 78.4 | 40.1 | 34.2 | 58.8 |

| 75–79 | 2124 (12%) | 81.8 | 78.3 | 39.9 | 33.4 | 58.4 |

| 80–84 | 3474 (19%) | 82.9 | 78.7 | 42.5 | 35.7 | 59.9 |

| 85–89 | 4408 (24%) | 82.3 | 78.0 | 42.9 | 36.2 | 59.8 |

| 90–94 | 3421 (19%) | 81.2 | 78.5 | 42.2 | 36.3 | 59.6 |

| 95–99 | 1406 (8%) | 81.3 | 78.5 | 39.8 | 33.2 | 58.2 |

| 100+ | 237 (1%) | 81.3 | 81.7 | 38.8 | 32.8 | 58.6 |

| Year of admission | ||||||

| 2012 (<6 months) | 3754 (21%) | 80.5 | 76.9 | 47.2 | 40.8 | 61.4 |

| 2011 | 4535 (25%) | 82.0 | 77.0 | 44.8 | 38.3 | 60.5 |

| 2010 | 3007 (17%) | 82.2 | 77.9 | 42.1 | 35.9 | 59.6 |

| 2007–2009 | 4613 (25%) | 82.7 | 79.7 | 37.6 | 31.4 | 57.9 |

| 2004–2006 | 1467 (8%) | 84.4 | 82.5 | 33.9 | 26.6 | 56.8 |

| Before 2004 | 792 (4%) | 84.7 | 83.8 | 34.0 | 27.4 | 57.4 |

| Admission type | ||||||

| Intermediate | 80 (<1%) | 82.9 | 83.6 | 55.9 | 55.4 | 69.5 |

| Respite | 417 (2%) | 82.9 | 78.0 | 53.6 | 49.2 | 65.9 |

| Convalescent | 91 (<1%) | 72.0 | 77.8 | 49.4 | 45.2 | 61.1 |

| Long-term care | 17 649 (95%) | 82.5 | 78.7 | 41.4 | 34.8 | 59.4 |

| End-of-life care | 283 (2%) | 70.2 | 73.0 | 29.6 | 26.5 | 58.4 |

| Resident category | ||||||

| Mental illness (excluding dementia) | 592 (3%) | 83.0 | 75.7 | 50.1 | 43.6 | 63.1 |

| Frail elderly | 9059 (52%) | 80.5 | 79.1 | 42.8 | 37.0 | 59.9 |

| Dementia care | 6896 (40%) | 84.6 | 78.0 | 39.9 | 32.4 | 58.7 |

| Young physical disabled | 723 (4%) | 82.1 | 81.1 | 37.6 | 32.7 | 58.4 |

| No of reasons for admission | ||||||

| 1 | 8322 (45%) | 83.7 | 80.5 | 43.2 | 37.0 | 61.2 |

| 2 | 5694 (31%) | 82.7 | 78.4 | 40.8 | 33.9 | 59.0 |

| 3 | 2776 (15%) | 81.0 | 76.4 | 39.6 | 32.9 | 57.5 |

| 4 | 1076 (6%) | 77.3 | 73.5 | 36.7 | 31.2 | 54.7 |

| 5 or more | 533 (3%) | 74.2 | 70.7 | 38.5 | 32.2 | 54.0 |

| Mobility | ||||||

| Fully mobile | 4771 (26%) | 87.6 | 79.9 | 64.1 | 57.6 | 72.4 |

| With assistance | 5876 (32%) | 80.7 | 77.3 | 48.9 | 42.7 | 62.4 |

| Totally dependent | 7628 (42%) | 80.1 | 78.8 | 21.9 | 15.3 | 49.0 |

| Visual impairment | ||||||

| None | 5524 (30%) | 84.7 | 80.9 | 46.1 | 39.3 | 62.8 |

| Moderate | 11 465 (62%) | 81.4 | 78.0 | 40.6 | 34.2 | 58.6 |

| Severe | 1609 (9%) | 79.3 | 75.3 | 33.4 | 27.8 | 54.1 |

| Hearing impairment | ||||||

| None | 11 269 (62%) | 84.0 | 79.8 | 44.0 | 37.3 | 61.3 |

| Moderate | 5471 (30%) | 79.4 | 76.6 | 37.7 | 31.7 | 56.3 |

| Severe | 1360 (8%) | 78.6 | 76.3 | 36.3 | 30.6 | 55.5 |

| Continence | ||||||

| Continent | 5460 (30%) | 83.2 | 79.1 | 62.7 | 57.9 | 70.7 |

| Urinary incontinence | 3048 (17%) | 80.7 | 76.0 | 47.0 | 40.7 | 61.1 |

| Faecal incontinence | 297 (2%) | 80.4 | 78.9 | 40.3 | 32.6 | 58.2 |

| Dual incontinence | 9413 (52%) | 82.3 | 79.2 | 27.7 | 20.4 | 52.4 |

| Confused | ||||||

| No | 6487 (35%) | 81.3 | 81.5 | 49.6 | 44.1 | 64.2 |

| Yes | 12 172 (65%) | 82.7 | 76.9 | 37.3 | 30.4 | 56.9 |

| Challenging behaviour | ||||||

| No | 12 800 (69%) | 83.1 | 81.7 | 43.5 | 37.3 | 61.5 |

| Yes | 5843 (31%) | 80.2 | 71.9 | 37.3 | 30.3 | 54.9 |

| Resident completion | ||||||

| Unaided | 1043 (5%) | 80.9 | 82.5 | 61.6 | 57.7 | 70.8 |

| With help | 8052 (42%) | 81.1 | 78.1 | 48.5 | 42.3 | 62.5 |

| Not answered | 3872 (20%) | 83.7 | 79.3 | 40.6 | 33.4 | 59.2 |

| Unable to complete | 6061 (32%) | 83.2 | 78.2 | 29.6 | 22.7 | 53.5 |

All responses

Overall, 18 617 responses with complete howRu data were analysed. The mean scores (on 0–100 scales), SD, SEM and skewness for each item were Discomfort, 82.30 (SD 22.68, SEM 0.17, skewness −1.08); Distress, 78.63 (SD 24.97, SEM 0.18, skewness −0.96); Disability, 41.70 (SD 31.60, SEM 0.23, skewness 0.22); Dependence, 35.33 (SD 29.97, SEM 0.22, skewness 0.37); and summary howRu score, 59.49 (SD 19.28, SEM 0.14, skewness −0.03). Note the large SD, showing the heterogeneity of care home residents.

Gender

Responses were received on 12 380 women (67%) and 6033 men (33%). The ratio of women to men is approximately 2:1. The scores on all dimensions are a little higher (better) for men than for women (howRu score 58.9 vs 60.6), but the differences are small. Given the large sample sizes used, these differences are statistically significant but are not important.

Age

The average age of residents was 83 (men 80.0, women 84.6). The mean health status of care home residents has little relationship to the age of resident for all of the howRu dimensions. In general, care home residents have poor Disability and Dependence scores, and much better scores for Discomfort and Distress. In this respect, care home resident population differs from people living in their own home, where health status tends to deteriorate with older age.7

At the age extremes, residents aged under 50 (mainly young physically disabled) had the lowest (worst) scores for Disability and Dependence, while those over 100 years old had the highest (best) Distress score.

Year of admission

Year of admission is a measure of length of stay (data were collected in June 2012). The average level of Distress and Discomfort (to a slightly lesser extent) improved gradually as length of stay increases, while Disability and Dependence became worse.

Admission type

Most residents (95%) were admitted to care home for long-term care. The remainder comprise respite/holiday care (2.2%), end-of-life care (1.5%), convalescent care (0.5%), and intermediate or subacute care (0.4%). Although these percentages are low, the large size of the study allowed us to look at differences in their health status. Those admitted for intermediate (subacute) care had a better health status on all dimensions than any other category.

Convalescent (rehabilitation) residents had poorer Discomfort than any other group apart from end-of-life care. Those admitted for end-of-life care had lower health status scores on all dimensions than any other group.

Resident category

Dementia care residents had better scores for Discomfort but have worst Dependence (lowest scores). Residents with mental illness other than dementia had worse Distress than any other category, but better scores for Discomfort, Disability and Dependence. Young physically disabled residents had the best scores for Distress, but worst for Disability.

Number of reasons for admission

Health status is strongly related to what is the matter with the resident.15 Most residents were recorded as having two or more health-related reasons for admission. In this study, the association was much less than for people living in their own homes,7 although all dimensions were associated with the number of reasons recorded. The smaller effect may be because most care home residents are already dependent. The largest impact was in terms of Distress (feeling low or worried) and Discomfort (pain and discomfort).

Mobility

Mobility was strongly associated with Disability and Dependence, modestly with Discomfort, but not with Distress.

Visual and hearing impairment

Both visual and hearing impairment were moderately associated with all four dimensions of howRu.

Continence

Continence was strongly associated with Disability and Dependence, but not with either Discomfort or Distress.

Confusion and challenging behaviour

Confusion and challenging behaviour were both moderately associated with Disability and Dependence. There is no association with Discomfort, but behaviour that is challenging is strongly associated with Distress.

Resident completion

The survey included a question about whether each resident was able to complete a patient-recorded questionnaire unaided, with assistance or was unable to complete it at all. This question was not answered for 20% of residents. Residents’ ability to complete the forms was strongly associated with their Disability and Dependence scores, but not with Discomfort or Distress.

Psychometric analysis

Table 5 shows the Spearman correlations between items and the aggregate howRu score. All correlations are highly significant (p<0.001). Cronbach’s α is 0.65, which suggests that in care homes health status represents more than one concept.12

Table 5.

Spearman correlations between items and the aggregate howRu score

| Item | Distress | Disability | Dependence | HowRu Score |

| Pain or discomfort (Discomfort) | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.53 |

| Feeling low or worried (Distress) | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.53 | |

| Limited in what he/she can do (Disability) | 0.84 | 0.83 | ||

| Require help from others (Dependence) | 0.81 |

Factor loadings are shown in table 6 showing two latent variables, with Disability (limited in what he/she can do) and Dependence (require help from others) being closely related (factor 1). The other two latent variables are Feeling low or worried (and Pain and discomfort (factor 2).

Table 6.

Rotated factor loadings

| Component Loadings | |||

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

| Pain or discomfort | . | 0.612 | 0.607 |

| Feeling low or worried | . | 0.689 | 0.510 |

| Limited in what he/she can do | 0.888 | . | 0.186 |

| Requires help from others | 0.893 | . | 0.191 |

Discussion

Practicality

This paper reports results from one of the largest studies of care home residents’ health status, as rated by staff. The good response rates indicate the practicality of the method used.

The study makes clear that health status is distinct from both diagnosis and physical and mental capability. Arguably, care for residents should be commissioned to meet assessed medical and disability needs but, in the absence of a clear end point, the use of an easily repeated PROM such as howRu can inform on the success of care individually and collectively.

The method used proved efficient when used at scale internationally and across continents. The bar-coded OMR forms were easy to complete and the scanning process was efficient and largely automated. The number of missing data and errors (such as marking two boxes when only one is allowed) were low. As digital transformation of care homes progresses, this health status measure could be incorporated into weekly routines providing a set of vital signs on health status.

Differences in national and regional response rates may be explained by the enthusiasm and engagement of local managers. New Zealand and Australia had the highest response rates (95% and 94%, respectively). New Zealand was the first to return all their forms. The manager responsible also asked several questions to clarify how to complete and return the forms. Unfortunately, we were not able to circulate the questions and answers given to all other homes. In future surveys, we recommended that a single person be appointed to coordinate all queries, circulate frequently asked questions and chase late responders.

At any time, about 95% of care home residents are admitted for long-term care, with the remaining 5% having shorter stays. The number of short-stay admissions is much greater than is indicated by the number of residents on a particular day and varies substantially between regions and homes.

This study is based on staff ratings of resident health status. Comparing staff reports and resident reports presents problems.5 Most care home residents suffer from cognitive impairment and are not able to complete surveys reliably. They adapt to the secure environment of a care home and may consider themselves to be less disabled and dependent than staff think they are. On the other hand, staff may also consider residents to have less discomfort and distress than residents report. Staff do not see residents 24 hours a day and may think that medication is more effective than it is.

Construct validity

Recording multiple variables allowed assessment of the construct validity of the measure used. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence of the construct validity of the howRu items and howRu summary score used in care homes, as well as insights into what is happening.

For example, we found little difference in health status between different age groups. This care home population differs considerably from that of people with long-term conditions, who live in their own homes, where health status is strongly associated with age. In the care home population, the correlation between Discomfort and Disability was low (r=0.14), but for people living in their own homes it was much higher (r=0.58).7 People become care home residents because they need physical care.

People with a longer length of stay had higher well-being (better Distress scores). This may be explained in part by adaptation to living in a residential care home. However, they were also more Dependent.

Different categories of admission type, resident category and number of reasons have distinct profiles of Discomfort, Distress, Disability and Dependence, which are as expected. Mobility, visual and hearing impairment, continence, confusion and challenging behaviour were strongly associated with Disability and Dependence, but less with Discomfort or Distress. We also found a strong association between Disability and Dependence scores and residents’ capability to complete parts of the survey unaided. The distribution of scores for each item was quite broad, showing that care home residents are far from being homogeneous. However, due to the large sample size, the confidence limits for the mean scores are small.

The evidence presented here only considers mean scores within this population. However, howRu has been validated at the individual patient level, which is essential if it is to be used to guide clinical decisions.10 This suggests that these ratings could have clinical uses.

Limitations

This study has limitations, some of which stem from the way that it was commissioned. This study was conceived as an aid to managers at international, country, region and care home level, not as academic research. Care home managers were responsible for collecting the data, which may have created some biases, although no evidence of bias has been detected.

One limitation of this study was that health status was recorded at a single point on time. This means that it was not possible to see how individual residents progressed over time. This study was quantitative only. Practicality and ease of use were assessed using response rates and completeness of data, not on qualitative study of the acceptability to staff or usefulness of the information. Such work needs to be done.

Following company reorganisation, this study did not lead to further work with Bupa. The study did not collect any qualitative data about the acceptability of the method to staff, residents, care homes or the organisation.

More recently, we have examined staff perceptions of the quality of service they provide to care home residents, their well-being at work and their confidence in doing their job.16

Conclusions

The method used to survey care homes proved very practical when used at scale. The howRu health status measure shows good construct validity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of Bupa Care Services, which funded the study, and to the care home staff and managers who took part.

Footnotes

Contributors: TB designed the surveys with CB and wrote the first draft of the paper. TB performed the analyses. CB and TB managed the data collection. All authors contributed to the final text, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: TB is a director and shareholder of R-Outcomes Ltd, which provides quality improvement and evaluation services in the health and social care sectors using howRu. CB was previously medical director of Bupa Care Services and is a non-executive director of AKARI Care Homes, FINCCH and Invatech Health, all of which have interests in care homes and social care. Please contact R-Outcomes Ltd if you wish to use howRu.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowman C, Whistler J, Ellerby M. A national census of care home residents. Age Ageing 2004;33:561–6. 10.1093/ageing/afh177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lievesley N, Crosby G, Bowman C. The changing role of care homes. Centre for Policy on Ageing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report BA, 2018. Available: https://www.bupa.com/~/media/files/site-specific-files/our%20performance/pdfs/financial-results-2018/annual-report-and-accounts-2018.pdf

- 5.Gordon AL, Franklin M, Bradshaw L, et al. Health status of UK care home residents: a cohort study. Age Ageing 2014;43:97–103. 10.1093/ageing/aft077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usman A, Lewis S, Hinsliff-Smith K, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life of care home residents: comparison of self-report with staff proxy responses. Age Ageing 2019;48:407–13. 10.1093/ageing/afy191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson T, Sizmur S, Whatling J, et al. Evaluation of a new short generic measure of health status: howRu. Inform Prim Care 2010;18:89–101. 10.14236/jhi.v18i2.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson T, Potts HWW, Whatling JM, et al. Comparison of howRU and EQ-5D measures of health-related quality of life in an outpatient clinic. Inform Prim Care 2013;21:12–17. 10.14236/jhi.v21i1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson T, Williams DH, Potts HWW. Performance of EQ-5D, howRu and Oxford hip & knee scores in assessing the outcome of hip and knee replacements. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 10.1186/s12913-016-1759-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendriks SH, Rutgers J, van Dijk PR, et al. Validation of the howRu and howRwe questionnaires at the individual patient level. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:447 10.1186/s12913-015-1093-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centre for Policy on Ageing A profile of residents in BUPA care homes: results from the 2012 BUPA census, 2012. Available: http://www.cpa.org.uk/information/reviews/Bupa-Census-2012.pdf [Accessed 2 Apr 2019].

- 12.Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 5th edn Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.JASP Team JASP (Version 0.10.0) [Computer software], 2018. Available: https://jasp-stats.org/

- 14.NHS Health Research Authority Defining research: research ethics service guidance to help you decide if your project requires review by a research ethics committee. UK Health Departments’ Research Ethics Service, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mujica-Mota RE, Roberts M, Abel G, et al. Common patterns of morbidity and multi-morbidity and their impact on health-related quality of life: evidence from a national survey. Qual Life Res 2015;24:909–18. 10.1007/s11136-014-0820-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benson T, Sladen J, Done J, et al. Monitoring work well-being, job confidence and care provided by care home staff using a self-report survey. BMJ Open Qual 2019;8:e000621 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]