We report the first subnanometer resolution structure of the RET extracellular domain in complex with a ligand and co-receptor.

Abstract

Signaling through the receptor tyrosine kinase RET is essential during normal development. Both gain- and loss-of-function mutations are involved in a variety of diseases, yet the molecular details of receptor activation have remained elusive. We have reconstituted the complete extracellular region of the RET signaling complex together with Neurturin (NRTN) and GFRα2 and determined its structure at 5.7-Å resolution by cryo-EM. The proteins form an assembly through RET-GFRα2 and RET-NRTN interfaces. Two key interaction points required for RET extracellular domain binding were observed: (i) the calcium-binding site in RET that contacts GFRα2 domain 3 and (ii) the RET cysteine-rich domain interaction with NRTN. The structure highlights the importance of the RET cysteine-rich domain and allows proposition of a model to explain how complex formation leads to RET receptor dimerization and its activation. This provides a framework for targeting RET activity and for further exploration of mechanisms underlying neurological diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Neurotrophic signaling drives the development, survival, and function of neurons (1). Neurturin (NRTN) is a neurotrophic factor that belongs to the GDNF (glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor) family of ligands (GFL). GFL members include GDNF, NRTN, ARTN (artemin), persephin, and GDF15 (growth/differentiation factor 15), which bind to specific co-receptors GFRα1-4 and GFRAL (GDNF family receptor α 1-4 and α-like) (2–4), followed by association with the extracellular portion of receptor tyrosine kinase RET (rearranged during transfection). The GFL-induced dimerization of the RET extracellular domain (ECD) triggers the activation of the intracellular RET kinase domains, leading to subsequent autophosphorylation of key tyrosine and serine residues (5). Phosphorylation within the kinase domains results in the formation of binding sites for adapter proteins that mediate the activation signal to cascade pathways required for vertebrate nervous system development, kidney development, and spermatogenesis (6). Aberrant RET signaling is involved in various human pathologies (7), including Hirschsprung’s disease, associated with abnormal development of the enteric nervous system and colon aganglionosis (8), and sporadic and familial cancers in neuroendocrine organs, including multiple endocrine neoplasias type 2A and 2B (MEN2A and MEN2B) and familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (9, 10). NRTN also promotes survival of dopaminergic neurons in culture and in vivo (11) and was developed as a possible treatment of Parkinson’s disease (12). Therefore, unraveling the molecular details of the NRTN-containing and related signaling complexes may be advantageous in the development of new therapeutics.

NRTN forms a homodimer with a cystine knot at its center (13) and requires the co-receptor GFRα2 to activate RET (14). GFRα2 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchored protein that consists of three structured domains (GFRα2D1-D3) and a flexible C terminus (13). The NRTN-GFRα2 complex is composed of a dimer of dimers with the NRTN homodimer at the center and two GFRα2 monomers attached (13). The NRTN-GFRα2 complex binds two copies of the RETECD, thereby forming a heterohexamer (2, 15). RETECD consists of four cadherin-like domains (RETCLD1-4) and a cysteine-rich domain (RETCRD) (16, 17). RETCLD2 and RETCLD3 coordinate calcium ions that are critical for RET folding. The previously available structural information on the heterohexameric complex is a negative stain electron microscopy (EM) 24-Å resolution map, combined with small-angle x-ray scattering data of the related GDNF, GFRα1, and RETECD from zebrafish, rat, and human, respectively, revealing the overall shape of a similar complex (18). Important questions concerning RET complexes remain, such as the nature of the relationship between RET-GFRα2 and RET-NRTN and the role of RETECD components in the function and dynamics of these complexes.

To address these questions, the extracellular part of the NRTN- and GFRα2-bound RET signaling complex has been reconstituted, and its structure was determined using single-particle cryo-EM to a resolution of 5.7 Å. A tilting approach (19) was crucial for the successful reconstruction of the heterohexamer to overcome particle orientation bias. The results show that one NRTN homodimer binds to two GFRα2 molecules, forming a V-shaped structure, while two RETECD molecules wrap around the GFRα2 and contact NRTN at the membrane-facing surface with the RETCRDs. Viewed from the top, the complex resembles a figure 8 with NRTN at the intersection and GFRα2 and RETECD molecules forming the ring-like structures. Detailed structural analysis identified the position of the RETCRDs, which gave insight into the positioning of the transmembrane helices and subsequent dimerization of the intracellular kinase domain. In addition, we observed inherent structural flexibility within the extracellular regions of the NRTN-GFRα2-RETECD complex. These structural findings explain gain-of-function mutations in RETECD and identify two key interface regions in NRTN and GFRα2 that are critical for heterohexamer formation and receptor activation.

RESULTS

Cryo-EM structure of NRTN-GFRα2-RETECD

To obtain structural insights into the biologically active RET signaling complex, we reconstituted the heterohexameric complex from purified mature human NRTN (amino acids 96 to 197), human GFRα2 (22 to 444), and human RETECD (29 to 635) in the presence of 20 mM CaCl2, which is required for RETECD folding. Further purification by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) resulted in a single symmetrical peak, indicating a homogeneous and monodisperse protein solution (fig. S1). Three-detector molecular weight determination by SEC-MALS (multiangle light scattering) revealed that the NRTN-GFRα2-RET complex and its separate components GFRα2 and RETECD were heavily glycosylated (fig. S1). The glycosylations increased the molecular weight of the heterohexamer by 30%, resulting in an observed molecular weight of 330 kDa rather than the theoretical weight ~250 kDa (fig. S1).

Initial visualization by cryo-EM established the symmetric 2:2:2 stoichiometry of the complex (13); however, preferential orientation in the sample prevented detailed structure determination (Fig. 1A). To overcome the limitations caused by the preferred specimen orientation of the complex, we collected two datasets using a 40° tilt angle (table S1, Fig. 1A, and fig. S2) (19) that improved the structural data to an overall resolution of 6.3 Å. The map quality was further improved upon symmetry expansion and signal subtraction, resulting in a nominal resolution of 5.7 Å for the monomer (Fig. 1B and fig. S2).

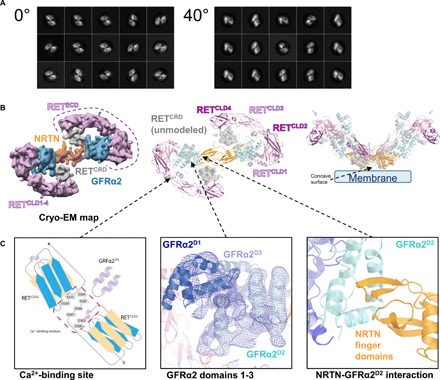

Fig. 1. Data collection at a 40° tilt angle enabled reconstruction of a cryo-EM map of the NRTN-GFRα2-RET complex at a 5.7-Å resolution.

(A) Comparison of two-dimensional (2D) class averages obtained from data collected at 0° or 40° tilt angles. 2D classes from the 0° data collection showed severe orientation bias of the molecule, exclusively presenting the view from the top revealing a figure 8 shape. 2D classes from data collected at the 40° tilt angle show a broader distribution of views. (B) Cryo-EM map reconstruction at a 5.7-Å resolution and atomic model derived from fitting in the cryo-EM map. Density around the NRTN dimer (or cartoon representation) is colored orange, GFRα2 is in blue, and RETCLD1-4 is in pink and magenta. Density for the unmodeled RETCRD is depicted in gray. Most of the density could be modeled, and only RETCRD could not be traced (gray, center). The side view of the complex suggests the position of the plasma membrane (right). (C) Schematic close-up view of the calcium-binding site between RETCLD2 and RETCLD3 (left), GFRα2 domains 1–3 showing the electron density (center), and the NRTN-GFRα2 interface mediated by the NRTN finger domain (right).

For model building, existing crystal structures of single domains of NRTN, GFRα2D1-D3 (13) [Protein Data Bank (PDB) codes: 5NMZ and 5MR4], and RETCLD1-2 (17) (PDB code: 2X2U) were fitted as rigid bodies and manually optimized using Coot (20) to match the electron density (Fig. 1B). Models of RETCLD3-4 were generated by homology modeling (18) (PDB code: 4UX8). The 43 disulfide bonds distributed over the six molecules of the structure model were structurally constrained during refinement. Because of relatively low local resolution, the connectivity of the RETCRD and RETCLD domains could not be determined and the RETCRD could not be modeled (Fig. 1B). In GFRα2, C-terminal residues 360 to 444 and loops within GFRα2D1 were not visible in the density. This was similar to the observation in the crystal structure of the NRTN-GFRα2 complex (13). The refined structural model contained 1688 residues (of 2264), and the correlation coefficient with the cryo-EM map was 0.919 as calculated using Chimera (21).

Description of the NRTN-GFRα2-RET complex

The complex exists as a homodimeric assembly with two molecules of NRTN forming the central homodimerization domain, through a large interface area of 2100 Å2 (Fig. 1B). The NRTN dimer contains six intra- and one intermolecular disulfide bridges and is arranged in a head-to-tail conformation such that the finger domains are pointing away from the center (Fig. 1C). GFRα2 and RETECD occupy lateral positions, resembling the shape of a figure 8 (Fig. 1B). GFRα2 contains three structurally conserved domains, GFRα2D1-D3, and a flexible C terminus. Each domain is composed of four helices and form a network of interactions to NRTN and RET. GFRα2D2 is essential for NRTN binding and is flanked by GFRα2D3, whereas GFRα2D1 is placed on the other side of GFRα2D3 and is in contact with RETCLD1 (Fig. 1B). RETCLD1 forms a clamshell-like domain with RETCLD2, and the latter extends to RETCLD3 through the calcium-binding site that is shared by the two domains (Fig. 1C, left). This arrangement is consistent with the previously determined crystal structures of NRTN-GFRα2 and RETCLD1-2 (13, 17). The intermolecular network is supported by residues from RETCLD2 and RETCLD3 that contribute to the binding of GFRα2D3. In addition, RETCLD4 extends from RETCLD3 and shares a large interface with the RETCRD, which completes the ring with NRTN by reaching back toward its concave membrane-facing surface. This places the NRTN surface and the RETCRD in direct contact with the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B, right).

Since the GFRα2 and RETECD proteins used in this study were expressed in mammalian cells, they carry near-native glycans. GFRα2 (22 to 444) contains 3 predicted N-linked glycosylation sites, and RETECD (29 to 635) contains 12 predicted N-linked glycosylation sites. Peptide mapping of RETECD confirmed that 11 of the predicted sites were glycosylated, and only N554 was unmodified when expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.

The presence of densities protruding from the ring-like structures, as seen in two-dimensional (2D) class averages, showed that at least six sugar moieties extend from the RETECD surface. The structure presented here suggests that these glycans are linked to N98, N199, N367, N377, N394, and N448 (fig. S3). In addition, N151, N336, N343, N361, and N367 are glycosylated as shown by peptide mapping. Some of these glycans are located at the inner surface of RETECD and point toward GFRα2 and/or NRTN (fig. S3).

Interactions between RETCLD1-4 and the NRTN-GFRα2 complex

RETCLD1-3 and GFRα2 share an interface area of 850 Å2. GFRα2 also interacts with parts of RET that are not modeled but are visible in the cryo-EM map (Fig. 2), i.e., RETCRD and diffuse densities attached to RETCLD3, which are likely sugar moieties. RETCLD4 is not in contact with NRTN or GFRα2 but has extensive interactions with the RETCRD. More than 13% of the residues in RETCLD1-2 are in direct contact with GFRα2, mainly GFRα2D3 (16 of 19 residues) and, to a limited extent, GFRα2D1 (3 of 19 residues), creating a large binding site that anchors the N-terminal domains of the RETECD molecule to the GFRα2 co-receptor. Interface 1 (Fig. 2A, bottom left) describes interactions between RETCLD1 and GFRα2D1, mediated primarily via two loops in GFRα2 (residues 91 to 94 and 121 to 126). The limited interactions observed between RETCLD1 and GFRα2D1 suggested that this domain was not critical for RETECD binding, as has been discussed before (22). To test this hypothesis, we produced a truncated GFRα2 protein, lacking the GFRα2D1 and flexible C terminus (amino acids 147 to 362). This truncated protein can form a 2:2:2 complex with NRTN and RETECD that eluted as a single peak, as shown by SEC (fig. S4). This demonstrates that neither GFRα2D1 nor the flexible GFRα2 C terminus was essential for RETECD binding.

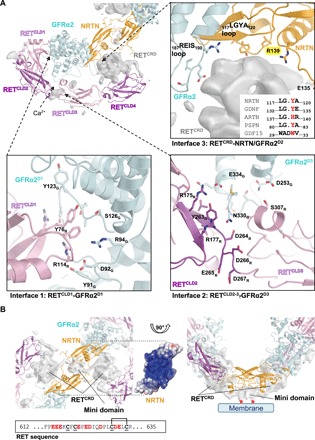

Fig. 2. Details of the RETECDinteractions.

(A) Unmodeled density (gray) and structural model of one protomer are shown. Three interfaces mediate the interactions between RETECD and GFRα2 and/or NRTN. Interface 1 (bottom left) comprises residues in the interaction surface between GFRα2D1 and RETCLD1. Selected side chains of residues involved in the interaction are depicted as sticks and labeled. The second interface (bottom right) includes residues around the calcium-binding site between RETCLD2 and RETCLD3 and residues in GFRα2D3. Selected side chains of interacting residues are depicted as sticks and labeled. Interface 3 (top right) is located at the center of the heterohexamer, where RETCRD is in contact with GFRα2 and the NRTN dimer. In GFRα2, a loop bearing residues 187 to 190 (187REIS190) is close to RETCRD (top right). In NRTN, the loop 117LGYA120, is in contact with RETCRD and is of special interest because the tyrosine residue (Y119) is semiconserved among all GFLs that all have an aromatic residue at this position (sequence alignment). A second loop (NRTN), bearing residues E135 and R139, is also close to RETCRD. (B) RETCRD C termini meet at the membrane-facing surface of the NRTN homodimer, close to the positively charged heparin-binding surface, forming a mini domain as a part of RETCRD. The RETCRD C terminus is rich in negatively charged residues (sequence) and could form tight electrostatic interactions with the positively charged cleft on the NRTN surface. The homotypic RETCRD interaction also suggests a mechanism for the activation of the constitutively active RET mutant C634R, which is common in patients with MEN2A (7, 28, 29). In this case, C630 remains unpaired and could form an intermolecular disulfide bond with the opposite RETCRD molecule. The right panel is rotated by 90° relative to the left panel, illustrating the proximity of the RETCRD mini domain to the membrane. The proposed location of the beginning of the transmembrane helices is highlighted by red asterisks.

Interface 2 (Fig. 2A, bottom right) consists of residues from GFRα2D3 and RETECD near the calcium-binding site in RETECD. Residues from a loop in GFRα2 (G327-N330) and a helix (L252-D253) contribute to binding in this region. The network of interactions suggests that calcium binding may be required not only for proper folding of RET but also for creating a binding surface for GFRα2. N330 of GFRα2 is 90% buried at the interface according to analysis by PISA (Proteins, Interfaces, Structures and Assemblies) (23), and its side chain points toward the calcium-binding groove between RETCLD2 and RETCLD3 and interacts with RET Y263 and the main chain amide of RET D264. The third interface (Fig. 2A, top right) includes interactions between the unmodeled RETCRD and NRTN and GFRα2.

The CRD forms homotypic interactions at the membrane-facing surface of NRTN

Although the local resolution for the RETCRD was not sufficient for complete model building, the density map enabled the identification of residues within NRTN and GFRα2 that were in contact with RETCRD at interface 3 (Fig. 2A, top right). These residues were distributed over three loops: the nonconserved residues 187 to 191 (REIS) from GFRα2, residues 117 to 120 (LGYA) from one NRTN protomer (NRTNA), and the nonconserved residues 135 to 139 (EAAAR loop) of the opposite protomer (NRTNB) in a domain-swapped manner. The NRTN LGYA loop bears the semiconserved Y119, which is an aromatic residue in all GFLs (Fig. 2A, top right and inset). The fact that three molecules (NRTNA, NRTNB, and GFRα2) are involved in the binding of RETCRD suggests that this interface is important for functional complex formation. This was further highlighted by the observation that, despite extensive interactions between GFRα2 and RETECD, neither GFRα2 nor NRTN alone could bind RETECD. This was shown by surface plasmon resonance (SPR; fig. S5) and has also been reported for the homologous proteins GDNF and GFRα1 (24). RETECD binds only after NRTN and GFRα2 have formed a bipartite stable complex (Fig. 3 and fig. S5) with the structure indicating a critical role for RETCRD during this process.

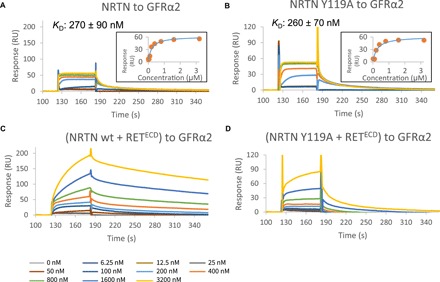

Fig. 3. Mutational analysis of complex formation by SPR.

(A and B) SPR was used to test the NRTN and GFRα2 mutants for binding to GFRα2 wild-type (wt) or NRTN wild type, respectively. As an example, we show NRTN Y119A binding to immobilized GFRα2 (B) in comparison to NRTN wild-type binding to immobilized GFRα2 (A). A list of KDs can be found in fig. S5F. KDs were determined by plotting the concentrations against the equilibrium responses (insets). (C) Sensorgram showing injection of equal concentrations of NRTN and RETECD to immobilized GFRα2. Since the response signal never reaches the equilibrium, the heterohexameric complex formation could not be analyzed quantitatively by SPR. However, the results show an increased response of approximately 150 RU compared to NRTN alone (A) and an apparent slower dissociation from the surface. Both observations are suggestive of heterohexameric complex formation. (D) Sensorgram showing injection of equal concentrations of the NRTN Y119A mutant and RETECD to immobilized GFRα2. The differences observed when comparing (C) with (A) were not observed for NRTN Y119A and RETECD binding to GFRα2 [(D) versus (B)]. A binding effect was observed at high protein concentrations (>1 μM), suggesting weaker binding affinity. This implicates that, under the conditions of the SPR experiment, the heterohexamer does not form with this NRTN mutant except at high protein concentrations.

The unmodeled RETCRD forms a globular domain, which is wedged between RETCLD4 and NRTN-GFRα2. However, additional density could be observed near the membrane-facing surface of NRTN, where the heparan sulfate binding site is located (Fig. 2B) (13). As there was no heparan sulfate analog present in the experiments, a likely explanation is that the two RETCRDs extend their C termini to this site, forming a dimeric mini domain as part of the RETCRD. This is further supported by a weak density connecting RETCRD to this mini domain, similar to that connecting RETCLD4 to RETCRD (Fig. 2B, gray surface). The membrane-facing NRTN surface is highly positively charged (13) and could therefore serve as an electrostatic binding platform for the dimerized RETCRD C termini with 40% anionic residues present (Fig. 2B). This suggests an additional function for the charged surface in addition to its role in heparan sulfate binding (13) and its potential interactions with the phospholipids in the cell membrane.

The cryo-EM density shows that the two RETECD protomers (29 and 635) have no interaction with each other, except for the last C-terminal residues, which dimerize on the membrane-facing surface of NRTN. The RET transmembrane helices, which follow the RETCRDs directly in sequence, would point away from the heterohexamer into the membrane (Figs. 1B and 2B, indicated by red asterisks). This explains why NRTN is essential for bringing the transmembrane helices of full-length RET close together to enable dimerization of the intracellular domains and signaling. It also suggests that the position and distance between the RET transmembrane helices are mainly dictated by the GFL.

Heterohexamer formation in SPR is impaired by the NRTN Y119A mutation

To assess the importance of the NRTN-RETCRD interaction, we constructed two NRTN mutants, Y119A of the LGYA loop and the E135S/R139A double mutant from the EAAAR loop (Fig. 2A, interface 3). NRTN Y119 of the LGYA loop is the only residue of those located at the NRTN-RETCRD interface that shows a degree of sequence conservation between GFLs, as all five family members bear an aromatic residue at this position (Fig. 2A, top right and inset). In addition, to investigate the contribution of the GFRα2D3 interaction with the calcium-binding site of RETECD, we produced the GFRα2 N330A mutant.

SPR was used to assess binding of mutant NRTN to wild-type GFRα2 and mutant GFRα2 to wild-type NRTN and measure equilibrium dissociation constants (Fig. 3 and fig. S5). It has previously been shown that the apparent affinity of NRTN for GFRα2 is dependent on the receptor concentration on the SPR chip. The KD (equilibrium dissociation constant) is 100-fold lower at high concentration of immobilized GFRα2 compared to a low concentration of GFRα2, which corresponds to a monovalent or bivalent binding site being presented by GFRα2 (13). Furthermore, the higher affinity measured by SPR using an Fc-fused GFRα2 (25) is likely the result of a bivalent interaction induced by Fc dimerization. The affinities reported here for the NRTN-GFRα2 interaction between wild-type and mutant proteins agree well with those corresponding to the monovalent interaction between NRTN and GFRα2 reported in the previous study (13). The SPR measurements showed that none of the mutations affected the binding between GFRα2 and NRTN (Fig. 3 and fig. S5) as the mutants formed bipartite complexes with KD in a similar range to the wild-type interaction (fig. S5F). This also confirmed that the mutant proteins were correctly folded. Since SPR was used to determine KDs for the NRTN-GFRα2 interaction, the same method was used to study the formation of the heterohexamer. When all the three components NRTN, GFRα2, and RETECD were combined, the SPR sensorgrams showed biphasic behavior (Fig. 3C), indicating that complex binding events were taking place. Because of the presence of multiple phases, quantitative determination of the affinities or binding kinetics for the formation of the heterohexameric complex could not be obtained, but several qualitative conclusions could still be drawn.

Comparison of the NRTN-GFRα2 interaction, where NRTN was injected over immobilized GFRα2 (Fig. 3A) with the experiment when the mixture of NRTN and RETECD was injected over immobilized GFRα2 (Fig. 3C), showed large differences in the binding profiles. Inclusion of RETECD resulted in much slower association and dissociation processes, suggesting slower formation of the larger complex that also dissociates slowly. The same behavior was observed when GFRα2 and RETECD were injected over immobilized NRTN (fig. S5C), demonstrating that the extracellular complex can form regardless of which component is attached to the surface. The change in binding profile upon addition of RET was not caused by unspecific binding, since, essentially, no binding was detected when RETECD alone was injected over a NRTN or GFRα2 surface (fig. S5, D and E).

In contrast, the Y119A NRTN mutant showed a distinctly different binding behavior when injected together with RETECD over a GFRα2 surface (Fig. 3D). Addition of wild-type NRTN and RETECD resulted in a markedly slower apparent association and dissociation compared to the bipartite complex (Fig. 3C). This was only seen at very high concentrations (more than 1 μM) in the corresponding experiment with the NRTN Y119A mutant (Fig. 3D), indicating an impaired ability of the Y119A mutant to form the heterohexameric complex.

Together, this suggests that the observations in the SPR experiments with all three components introduced represent the formation of the heterohexameric complex. This complex formation is impaired with the NRTN Y119A mutant, suggesting weaker binding to the RETECD.

Interface 2 is critical for heterohexamer formation

To address further the significance of the interaction surfaces between RETECD and NRTN/GFRα2, we tested the ability of the NRTN (Y119A and E135S/R139S) and GFRα2 (N330A) mutant proteins to form the heterohexameric complex with RETECD using SEC-MALS. In agreement with the SPR experiments (Fig. 3 and fig. S5), all proteins tested were able to form stable bipartite NRTN-GFRα2 complexes. The purified complexes were mixed with RETECD and analyzed. The wild-type heterohexameric complex eluted as a single large peak, while a smaller peak corresponded to the size of unbound GFRα2 (Fig. 4). Both NRTN mutants were also capable of forming the hexameric complex with wild-type GFRα2 and RETECD. However, despite excess amounts of NRTN-GFRα2, the complex formation using the Y119A mutant also resulted in a smaller peak corresponding to unbound RETECD, which could indicate reduced stability of the complex (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained when using chemical cross-linking to stabilize the assembled complexes. The two NRTN interface mutants under these experimental conditions were able to form a heterohexamer that could be stabilized by chemical cross-linking and observed on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel (Fig. 4C). Composition of the bands on the SDS-PAGE gel was confirmed by peptide mapping. The SPR data suggested that complex formation was initiated only at high protein concentrations (>1 μM; Fig. 3D), which is consistent with the complex assembly experiments for SEC-MALS analysis and chemical cross-linking, where the concentration of NRTN-GFRα2 complex was 5 μM. This concentration greatly exceeds physiological protein levels but is required for the detection on SEC-MALS.

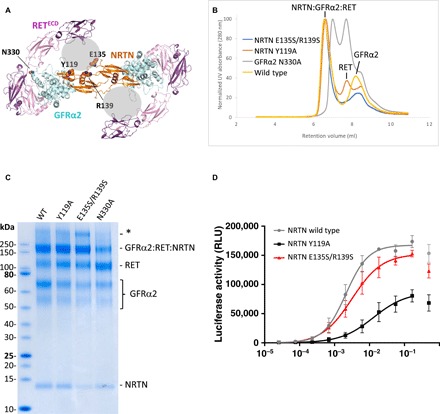

Fig. 4. Analysis of complex formation and signaling capacity of wild-type and mutant proteins.

(A) The mutated residues in interfaces 2 and 3 shown on the cryo-EM structure as viewed from the membrane. Modeled parts of the structure are shown as cartoon: NRTN (orange), GFRα2 (blue), and RETCLD1-4 (pink/magenta). Mutated residues are shown as spheres. The gray spheres represent the unmodeled RETCRD. (B) SEC-MALS ultraviolet (UV) traces after incubation of the NRTN-GFRα2 complex with RETECD (excess NRTN-GFRα2) show that a large peak, corresponding to the extracellular portion of the signaling complex, is formed with wild-type NRTN (yellow) as well as the NRTN mutants Y119A (red) and E135S/R139S (blue). Labeled peaks elute at the same retention volume as the complex components when run separately under the same conditions. An additional peak in the red trace (Y119A) represents RETECD that is not in complex. Incubation with the GFRα2 mutant N330 (gray) resulted in two major peaks, one corresponding to the elution volume of RETECD and one with a molecular weight lower than the hexameric complex. (C) SDS-PAGE gel showing samples from chemical cross-linking of heterohexameric complex with wild-type NRTN, Y119A, E135S/R139S, and GFRα2 N330A. Peptide mapping confirmed the identity of the SDS-PAGE gel bands. A larger band (marked with an asterisk), corresponding to approximately twice the size of the NRTN-GFRα2-RET complex, was shown by peptide mapping to also contain NRTN, GFRα2, and RETECD. This putative dimer was, however, not observed on SEC-MALS and is most likely a gel or cross-linking artifact. (D) The NRTN-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling through RET measured in a human neuroblastoma (TGW) cell–based activity reporter assay. The average of three separate experiments is reported, and each experiment was run with four replicates. The top concentration of NRTN resulted in a reduced signal, which is commonly observed in luminescence assays, and has therefore been excluded from calculation of EC50 and maximal signal. EC50 values are listed in Table 1. RLU, relative luminometer units.

The cross-linking experiments using the GFRα2 N330A mutant, on the other hand, showed a weaker band for the hexameric complex, indicating that less of the complex was formed. In addition, the hexameric complex as analyzed by SEC-MALS could not be observed for this mutant. The SEC trace looked distinctly different from that obtained with wild-type GFRα2 with two major and one smaller peaks (Fig. 4B). One of the large peaks corresponded to unbound RETECD in retention volume, and the smaller peak eluted at the same volume as unbound GFRα2, suggesting dissociation of the complex. The second large peak had a retention volume of 7 ml and was right-shifted compared to the wild-type heterohexameric complex. Because of partial overlap between the peaks, its precise molecular weight could not be determined by SEC-MALS. The matched cross-linking experiments did not show degradation or other stoichiometric variants of the complex or its components (Fig. 4C).

Together, these data suggest that NRTN residues E135, R139, and Y119 are dispensable for complex formation and integrity. However, even at a high protein concentration, a small portion of the RETECD is not in complex with Y119A NRTN-GFRα2 after SEC. In contrast, the interaction between RET and GFRα2 at interface 2 is essential for heterohexamer assembly and stability, as the GFRα2 N330A mutant protein forms less of the heterohexamer in cross-linking and there is no heterohexamer detected after SEC.

Y119A mutation attenuates RET signaling

To assess the functional effects of the interface mutations, we measured NRTN-induced RET signaling in a human neuroblastoma cell line (TGW). The cell line has been modified to contain a luciferase-encoding gene under the control of serum response elements (26). Addition of wild-type NRTN to the cells will result in correct assembly of NRTN, GFRα2, and RET and trigger luciferase generation via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling through RET. The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values of wild-type and mutant NRTN required to reach half-maximal RET signaling are listed in Table 1. The Y119A NRTN mutant showed reduced signaling capacity in the cell-based assay. The EC50 was increased sixfold for the Y119A mutant compared to wild-type, and the maximal signaling response was half that of wild-type NRTN (Fig. 4D and Table 1). This shows that the interaction between the LGYA loop of NRTN and RETCRD is required for efficient RET signaling. The E135S/R139S double mutant showed a slight reduction in signaling capacity in the reporter gene assay, with a 1.5-fold increase in EC50 and a maximal signal reached of 91% compared to wild type. In summary, these data show that, although all three targeted NRTN residues are located within interface 3 and in direct contact with RETCRD, the replacement of E135 and R139 had a limited effect on cell signaling, while removal of the side chain of Y119 markedly reduced the cell signaling capacity. Together, with the results from the in vitro complex assembly, these data show that both interfaces 2 and 3 are crucial for the NRTN-induced RET signaling, either for assembly of the heterohexameric complex or correct placement of the RET transmembrane helices to enable intracellular dimerization or both.

Table 1. EC50values of NRTN mutants and wild type.

The EC50 value represents the protein concentration required to obtain the half-maximal downstream signaling effect in TGW cells. Span of maximal signal of luciferase activity listed. Average of three experiments (Fig. 4D), four replicates per experiment. Reported SE is SEM.

| Protein | EC50 (ng/ml) | SE |

Max signal (RLU) |

SE |

| Wild-type NRTN |

2.1 | 1.2 | 167,500 | 6660 |

| NRTN (Y119A) |

13.0 | 1.8 | 86,820 | 17,290 |

| NRTN (E135S/ R139S) |

3.2 | 1.3 | 152,500 | 10,190 |

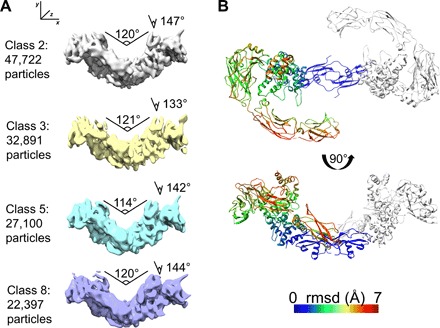

Conformational flexibility of the RET signaling complex

To reveal potential conformational differences for the heterohexamer within the cryo-EM sample, we performed a local 3D classification of 186,903 particles. This analysis yielded eight separable states that differed in the angle between the NRTN dimer and the ring-shaped structures of GFRα2 and RETECD. The four best classes were refined (Fig. 5). The NRTN homodimer contains a cystine knot in the center of the molecule, consisting of six intramolecular disulfide bonds and one intermolecular disulfide bond between C164 from both protomers (13). Since the cystine knot provides local rigidity in this region, it was used to superimpose the different states observed (Fig. 5B). This comparison showed that class 2 had the widest angle (147°) along the z axis, class 3 showed a 133° angle along the z axis, and classes 5 and 8 were quite similar along the z axis (142° and 144°) but varied along the x axis (114° and 120°). Variation in angles within the NRTN-GFRα2 complex has also been observed previously when comparing NRTN-GFRα2 crystal structures (fig. S6) (13). The two reported complexes, one formed with full-length GFRα2 and the other with the truncated co-receptor lacking GFRα2D1, display different angles between the GFRα2 protomers (115° and 126°, respectively). These results show that RETCLD1-4 and GFRα2 have a degree of conformational freedom with respect to the rigid NRTN homodimer, which can be observed in solution, and it is possible that this flexibility is also present when the membrane-facing surface of the NRTN dimer and the RETCRD are anchored to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5 and fig. S6). This flexibility, observed in solution samples, agrees well with the ability of the RET receptor to bind a variety of ligands and co-receptors.

Fig. 5. 3D auto-refinement reveals four conformations differing in angles of ring-like structures toward the NRTN dimer.

(A) Four classes of particles (minimum of 22,000 per class) were selected after 3D refinement and compared to each other. The overall structure of each protein subunit, NRTN, GFRα2, and RETECD, was not altered, but the position of the ring-like structures (GFRα2 and RETECD) in relation to the NRTN dimer differed between the classes. Two kinds of movement could be observed, one along the x axis and one along the z axis. Angles varied from 114° to 121° along x and 133° to 147° along z. (B) Comparison of the four models derived from maps in (A). One protomer from class 8 is colored by backbone root mean square displacement (RMSD) values compared to class 8. Top: Top view with NRTN superposed. Most movement occurs in RETCLD3 and RETCLD4. Bottom: A 90° rotated view.

DISCUSSION

The molecular details of RET activation by GFL-GFR pairs were elusive for a long time. This work shows the organization of the extracellular portion of the ligand-bound RET receptor in complex with NRTN and GFRα2.

We demonstrate that the RETECD interacts with NRTN-GFRα2 via a large surface area, where RETCLD1-3 interacts with GFRα2 domains 2 and 3, and the unmodeled RETCRD is in contact with NRTN and GFRα2. The NRTN homodimer is at the center of the complex with RET and GFRα2 forming two ring-like structures around it. The two RET monomers, however, are completely separated from each other, except for the C-terminal part of the CRD domain (Fig. 1). Despite large interaction surfaces, GFRα2 and RETECD do not associate in the absence of NRTN (fig. S5E), and the assembly of the heterohexamer requires the NRTN-GFRα2 complex to be formed with subsequent association of the RET monomers. The structure visualizes that the two 68-kDa RETECD monomers come together just before the transmembrane helices. The C termini of the CRDs from each RET monomer thereby dimerize on the membrane-facing surface of NRTN. This highlights that NRTN, and by inference, other GFLs, plays an essential role in placing the transmembrane helices at an optimal distance for signal transduction. It also suggests that the placement of the transmembrane part will differ depending on which GFL is inducing the signaling, and it is tempting to speculate that this dictates the route of intracellular signaling.

It can be seen that RETECD interacts with NRTN-GFRα2 through three distinct interfaces (Fig. 2), two of which that we, by mutational analysis, demonstrate are essential for complex formation and/or signal transduction. The RET calcium-binding site within interface 2 is important not only for proper RET folding but also for forming a binding platform for GFRα2D3, since the N330A mutant of GFRα2 fails to form a stable heterohexameric complex. A similar mechanism has been described previously for RETECD binding to the related GFRα1 (18). Interface 1, on the other hand, involves residues within GFRα2D1, which we show is generally dispensable for complex formation in vitro. The importance of interface 3 was confirmed by mutational analysis of NRTN Y119, which is in direct contact with RETCRD. The Y119A mutant was able to form the extracellular hexameric complex but was deficient in RET signaling. We therefore speculate that Y119 plays a role in correctly positioning the RETCRDs in proximity of each other. Other GFLs also contain an aromatic residue at this position (tyrosine or histidine; Fig. 2A, inset) and may therefore play a similar role in RETCRD binding. Our results agree with those reported for the NRTN homolog GDF15 where W32, which aligns in sequence and structure to Y119 (Fig. 2A, inset), is critical for GDF15 induced RET signaling in vivo (4).

The structural information has provided an understanding of how NRTN and GFRα2 interact with the receptor tyrosine kinase RET and provides a rationale for how the interaction enables RET dimerization and activation. In particular, the location of the RETCRDs suggests that the RET transmembrane helices, which follow the RETCRDs directly in sequence, enter the membrane just below the NRTN homodimer (Figs. 1B and 2B, indicated by red asterisks). This implies that NRTN binding brings the C termini of RETCRDs, and thus the transmembrane helices, close to one another such that the intracellular kinase domains come into proximity, allowing activation through transphosphorylation. This explains why a GFL is essential for RET activation, which cannot be achieved by the co-receptor alone. It is also possible that the interaction between the GFLs and the C termini of the RETECDs differs between the GFLs and that this will drive selectivity and downstream effects.

Elucidation of the structure provides an insight into the potential mechanisms leading to disease. MEN2A and MEN2B are specific types of thyroid cancer caused by gain-of-function mutations of RET, which render the receptor constitutively active (27). Notably, mutations of cysteine residues in RETCRD cause covalent dimers that lead to an oncogenic activation of RET kinase (7, 28, 29). Cysteines in RETCRD are thought to form a network of disulfide bonds of unknown organization. The frequently mutated C634 in patients with MEN2A is part of the RETCRD, in which wild-type RET forms a disulfide bond with C630 (18). In the structure presented here, unmodeled density suggests that the C termini of the two RETCRDs that harbor C634 and C630 join to form a mini domain at the membrane-facing surface of NRTN. This supports a model where NRTN (and other GFLs) is instrumental in bringing the two C termini together. The MEN2A C634R mutation leaves C630 unpaired and thereby available for putative intermolecular disulfide bonding at the face of NRTN. This would result in a covalent link between two RET molecules proximal to the extracellular membrane, with the kinase domains forming dimers, which leads to a constantly active receptor. The C634R mutation is generally considered to cause ligand-independent dimerization of RET, as demonstrated in cell-based assays overexpressing RET (7, 30). However, neither the RETECD nor RETECD bearing the C634R mutation forms dimers in solution, even at high concentration (18). Our structure is consistent with an alternative mechanism in which ligand binding is a required step before receptor dimerization can be efficiently achieved. A subsequent ligand dissociation step, leaving RET in its active state, is conceivable.

The positively charged membrane facing surface of NRTN has previously been shown to bind heparan sulfate with residues (R149, R152, R156, R158, R160, and Q162) from both protomers contributing to the coordination of sulfate ions (13). The cryo-EM structure suggests an additional role for the membrane-facing NRTN surface in binding the negatively charged C terminus of RETCRD via electrostatic interactions (Fig. 2B), which should be further investigated. Other GFLs are less positively charged than NRTN and have different charge distribution (e.g., GDNF). As a result of this, the interaction between those GFLs and RETCRD would be expected to differ. A previous negative stain study on human GDNF-GFRα1-RET complex showed an additional large mass of nonconnected density a short distance away from the membrane-facing side of GDNF that was interpreted as the flexible GFRα1 C terminus and the RETCRD C terminus (18). The cryo-EM reconstruction presented here does not contain any such density, despite constructs of similar size. However, the difference may be due to alternative binding modes between these related proteins. Unlike NRTN, GDNF has positively charged patches located at the N termini that extend from the membrane-facing surface, and this difference alone could affect CRD binding and placement of the transmembrane helices.

In addition, different conformations within the NRTN-GFRα2-RETECD complex in the cryo-EM reconstruction were identified (Fig. 5). This suggests that NRTN functions like a hinge with a circular movement of its ring-like structures (GFRα2-RETECD). The difference in angle has also been observed between different crystal structures of the NRTN-GFRα2 complex (fig. S6) (13).

Variation around the hinge between crystal structures of GFL-GFRα pairs has been discussed previously (31). The conformations observed between GDNF-GFRα1, NRTN-GFRα2, ARTN-GFRα3, and GDF15-GFRAL vary greatly in the overall shape and the angle of the co-receptor toward the ligand (fig. S6) (3, 32, 33). This emphasizes the intrinsic flexibility of RET, which enables the receptor to accommodate a variety of ligand–co-receptor complexes. The cryo-EM structure presented here highlights that, in addition to different conformations between related GFL-GFR complexes, there is also variation within the same type of complex in solution (Fig. 5).

In all structural studies, to date, the lack of RET or the RET transmembrane region and the absence of the membrane itself may have influenced the shape of the complexes as determined by crystallography. However, it is tempting to speculate that the different conformations observed in all extracellular GFL-GFR complexes so far (13, 33) could influence the dimerization of the extracellular and intracellular RET domains and that this might lead to variations in the RET-induced phosphorylation pattern (34). This could offer a model where binding of a unique GFL-GFRα complex directs which RET signaling pathway is activated. Given its crucial role in tumor formation and neurological disease, elucidating the molecular details of the RET receptor is instrumental in gaining new mechanistic insights into the regulation of RET signaling, which will offer a blueprint for future drug development endeavors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

Human NRTN and NRTN mutants were purified according to previously published protocols (13). Briefly, the coding sequence for residues 97 to 197, preceded by a 6× His-tag and a TEV (Tobacco Etch Virus) cleavage site, was cloned into a pET24a vector and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) Star via autoinduction at 25°C. Resulting inclusion bodies were dissolved in 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaPO4, 8 M urea, and 10 mM TCEP (tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine), and NRTN was refolded by rapid dilution into 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 3 M urea, 75 mM NaPO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM glycine, 4 mM cysteine, and 15% (w/v) glycerol. NRTN was extracted by Ni affinity chromatography using 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 300 mM NaCl, 75 mM NaPO4, and 15% (w/v) glycerol, containing 100 mM imidazole for the wash step and 500 mM imidazole for elution. The His-tag was removed using TEV protease (produced in house) at a molar ratio of 1:10 for 16 hours at 4°C, while being dialyzed against 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.2), 300 mM NaCl, 75 mM NaPO4, and 15% (w/v) glycerol. The cleaved protein was passed over the Ni–nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin, and the flowthrough was collected. As a final purification step, NRTN was purified on Heparin Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mM NaPO4, 100 mM NaCl, and 15% (w/v) glycerol. The protein was eluted with a linear gradient to 2 M NaCl, and dimeric NRTN was eluted at ~1 M NaCl. NRTN was aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

GFRα2 wild type and mutants were produced as described previously (13). Briefly, the gene encoding human GFRα2 (22 to 441), preceded by a CD33 secretion signal and with a C-terminal 6× His-tag, was expressed in CHO cells after transient transfection. The protein was purified directly from the cell culture supernatant using Ni-NTA resin equilibrated in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 500 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole. GFRα2 was eluted in buffer containing 500 mM imidazole, and fractions containing GFRα2 were combined and purified by SEC chromatography (Superdex 200) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 300 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol.

Human wild-type and mutant RETECD (1 to 635), followed by a TEV recognition site and a 6× His-tag, was purified from CHO cells after transient transfection. RETECD was extracted from the cell culture supernatant using Ni-NTA sepharose in 10 mM tris (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted with buffer containing 300 mM imidazole and cleaved overnight with TEV protease at a molar ratio of 1:10. The sample was dialyzed during cleavage to remove excess imidazole and subjected to a second Ni-NTA purification step to remove uncleaved RETECD and the free His-tag. As a final purification step, RETECD was purified using SEC (Superdex 200) equilibrated in 10 mM tris (pH 8), 200 mM NaCl, and 5 mM CaCl2. Protein containing fractions were combined, concentrated to ~1.5 mg/ml, flash-frozen, and stored at −80°C.

Complex formation

The complex between NRTN and GFRα2 was formed by combining the proteins and incubating them for 3 hours at 4°C. Gel filtration was carried out on the mixture using a Superdex 75 column [50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol] to separate monomeric proteins from the NRTN-GFRα2 complexes. Peak fractions were combined and added to human RET at a molar ratio of 1:2 in the presence of 20 mM CaCl2. Proteins were incubated for 3 to 16 hours at 4°C and purified via SEC (S200) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM CaCl2. Protein complexes were concentrated to 15 to 30 mg/ml, aliquoted, flash-frozen, and stored at −80°C.

Samples for cryo-EM were not concentrated, but the peak fraction (at ~1 mg/ml) was instantly used for grid preparation.

EM data acquisition and image processing

Three microliters of purified NRTN-GFRα2- RET complex at a concentration of ~1.6 μM was incubated for 10 s on glow-discharged holey gold grids (UltrAuFoil R1.2/1.3) in a Vitrobot MkIV (3-s blot, 4°C, 100% humidity). Images were collected on a 300-kV FEI Titan Krios electron microscope using a slit width of 20 eV on a GIF Quantum energy filter. A Gatan K2 Summit detector was used in counting mode at a magnification of 130,000 (yielding a pixel size of 1.05 Å) and a dose rate of ~5.2 electrons per pixel per second. Exposures of 8 s (yielding a total dose of 38 eÅ−2) were dose-fractionated into 20 movie frames that were stacked into a single MRC stack using newstack. A total of 2242 images were collected using E Pluribus Unum (EPU) automatic data collection across two independent sessions with defocus values ranging from 0.4 to 4.5 μm and a stage tilt of 40°.

Collected micrographs were corrected for local-frame movement and dose-filtered using UcsfDfCorr (35). The contrast transfer function parameters on a per-particle basis were estimated using GCTF-0.5 (36), and RELION-2.1.b1 was used for all other image processing steps. (37). The two datasets were processed independently up to 3D refinement, where the particles were then joined within RELION. Particles (340,661) were picked using reference-based picking, and bad particles were removed by extensive reference-free 2D class averaging, resulting in 186,903 particles for 3D auto-refinement. This yielded a consensus reconstruction with a nominal resolution of 7.0 Å. Fine-angular 3D classification was used to further identify flexibility in the complex yielding four classes with resolutions ranging from 7.4 to 9.1 Å. Since the complex is a dimer, the reconstruction of the monomer was improved by symmetry expansion. Particles were rotated around the C2 axis, and one copy of the dimer was signal subtracted. The remaining copy was aligned to obtain a 5.7-Å resolution consensus monomer reconstruction.

Reported resolutions are based on gold-standard refinement applying the 0.143 criterion on the FSC (Fourier Shell Correlation) between reconstructed half-maps. The FSC was corrected for the effects of a soft mask using high-resolution noise substitution (38). All 3D refinements used a 60-Å low-pass–filtered initial model, the first of which was a reconstruction calculated ab initio using RELION. Before visualization, all density maps were corrected for the modulation transfer function of the detector and then sharpened by applying a negative B-factor that was estimated using automated procedures (39).

Model fitting

First, all available PDB models were fitted onto the 5.7-Å cryo-EM map (NRTN, 5NMZ; GFRα2, 5AQ3; RET CLD1-2, 2X2U; RET CLD3-4, 4UX8). The RET CLD3-4 model was not based on a high-resolution structure but had been modeled on the basis of a sequence homology and a 24-Å resolution map published previously (18). Each protein and CLD were treated separately and fitted in Chimera to optimize map-to-model correlation. The hexamer with the optimal fit was assembled through combination of molecules that fit the map with the highest correlation. Following model fitting in Chimera, the model and map were inspected in Coot (20). Secondary structure elements were fitted separately, where the map-to-model correlation was not ideal (e.g., GFRα2 amino acids 39 to 61). During all adjustments, multiple disulfide bonds were considered. In total, 43 disulfide bonds were present in the modeled molecules, not including the predicted ones in the RETCRD. Stereochemical refinement was performed using rosetta with torsion restraints (40). The final correlation coefficient between the model and the map was 0.919. Statistics of the refinement are available in table S1.

RET peptide mapping

An SDS-PAGE gel band containing ~5 μg of RET protein was excised and washed with 50% acetonitrile/100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The protein sample was reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol/100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and then alkylated using 15 mM iodacetamide/100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. After washing twice with 40% acetonitrile/200 mM ammonium bicarbonate, the RET gel band was deglycosylated with peptide N-glycosidase F. Trypsin and chymotrypsin were added for protein fragmentation, which were extracted with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and 60% acetonitrile. The resultant digests were loaded onto the Dionex U3000 NanoLC for ESI-LC-MS (electrospray ionization-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) analysis using the Qstar Elite mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometry data were searched against the RET sequence using the Mascot search engine. Asparagine residues predicted to be glycosylated were changed to aspartic acids in the search sequence. Eleven of 12 predicted glycosylation sites in the RETECD were glycosylated in this sample: Asn98, Asn151, Asn199, Asn336, Asn343, Asn361, Asn367, Asn377, Asn394, Asn448, and Asn468. No glycosylation was detected at Asn554. Peptide mapping for cross-linked GFRα2, RET, and NRTN was carried out in a similar fashion, except that a Sciex X500B mass spectrometer was used.

Surface plasmon resonance

SPR experiments were conducted on a Biacore 3000 instrument (GE Healthcare) using CMDP (2D carboxymethyldextran surface) sensor chips (XanTec bioanalytics GmbH) at 20°C. NRTN was immobilized using amine coupling (Biacore Handbook, GE Healthcare) with phosphate-buffered saline as a continuous flow buffer. The sensor surfaces were conditioned using 0.1 M sodium borate and 1 M NaCl (pH 9.0) before activation by injecting a mix of 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide for 7 min. Approximately 100 nM NRTN in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5) was injected over the activated surface and immobilized to ~35 to 200 RU (resonance units). Any reactive groups still present were deactivated by injecting 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 7 min. A surface subjected only to activation and deactivation was also made to be used as a reference surface. Similarly, GFRα2 was immobilized by amine coupling as described above.

The interaction analyses of GFRα2, RETECD, or a complex thereof injected over immobilized NRTN were conducted using 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2 as running buffer at 20°C. GFRα2 and RET were diluted in running buffer to give concentration series up to 3.2 or 10 μM (monomer concentrations). Samples and blank injections were injected in quick succession for 60 s over immobilized NRTN and the reference surface, followed by 300 s of dissociation. The resulting sensorgrams were-reference subtracted and blank-subtracted. NRTN or NRTN/RETECD binding to immobilized GFRα2 was analyzed in 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.2), 200 mM MgSO4, and 10 mM CaCl2 to reduce unspecific binding of NRTN to the dextran matrix. All KD values were obtained by fitting a standard 1:1 Langmuir binding isotherm to the equilibrium responses for each concentration.

Analytical SEC

Analytical gel filtration experiments were conducted using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (column volume, 24 ml; GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min at 21°C. Before injection of the protein samples, the column was equilibrated with 20 mM Hepes (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM CaCl2. Elution profiles were monitored by ultraviolet (UV) absorption at 280 nm. The void volume (V0) was determined with blue dextran (Sigma). The column was calibrated with a protein standard (Bio-Rad) containing thyroglobulin (670 kDa), bovine γ-globulin (158 kDa), chicken ovalbumin (44 kDa), equine myoglobin (17 kDa), and vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa). Protein complexes were incubated for 16 hours at 4°C before injection onto the column.

For SEC-MALS, the complex between NRTN and GFRα2 was formed by mixing the proteins (an excess of NRTN was used) in a buffer consisting of 25 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol and incubating at 4°C overnight, with end-over-end mixing. To separate the complexes, the protein mixture was applied to a 16/60 Superdex 75 column and eluted at 1 ml/min. Peak fractions of the GFRα2-NRTN complex were pooled and combined with RET in the presence of 20 mM CaCl2. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 3 hours with end-over-end mixing, before concentration to approximately 1 mg/ml and analysis via SEC-MALS.

Size exclusion chromatography–multiangle light scattering

Protein size determination was carried out using a Malvern OMNISEC RESOLVE/REVEAL system, in a mobile phase of 20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min using a Sepax SRT SEC 300 (7.8 mm × 300 mm) at 20°C. Data were processed using either Omnisec v10 or v5 (for conjugate analysis). The total mass of peptide and glycosylation fractions was calculated for RET-GFRα2-NRTN, GFRα2-NRTN, GFRα2, and RET using the three-detector method (fig. S1) with a dn/dc (refractive index increment) of 0.147 for the glycan component. The column was selected for optimal resolution of the hexameric complex, and under these conditions, the RI (refractive index) and UV signals from NRTN was obscured by buffer agents and could not be detected.

Protein cross-linking

NRTN (30 nmol) and 2 nmol of GFRα2 and RET or mutants thereof were incubated at 4°C for 16 hours. BS3 cross-linker (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added at 0- and 2500-fold molar excess, and the samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 50 mM, followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min. The samples were analyzed by 4 to 12% SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie staining.

Activity assessment of NRTN mutants

These experiments used the human neuroblastoma cell line TGW-SRE-Luc clone N (JCRB0618, originally from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources). The cell line stably expresses a reporter gene construct containing a luciferase gene under the control of repetitive serum-response elements (SREs) (26). The expression of luciferase is dependent on MAPK pathway activation mediated by NRTN, and luciferase expression was measured using the Britelite plus Ultra-High Sensitivity Luminescence Reporter Gene Assay System (6066761, PerkinElmer).

Before seeding cells for assay, 96-well plates (6005070, PerkinElmer) were manually coated with 50 μl of collagen I (final concentration, 40 μg/ml in 0.2% acetic acid) per well and let to air-dry overnight at room temperature in a Biosafety cabinet class II. One day before stimulation with NRTN mutants, cells were detached using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (25200, Gibco), seeded at 60,000 cells per well in 90 μl of complete culture medium [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 (31331028, Gibco), 10% fetal bovine serum (10270, Gibco), and 15 mM Hepes (15630080, Gibco)] on collagen I–coated 96-well plates and allowed to attach overnight in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2.

NRTN mutants were serially diluted in DMEM/F12 medium without any additives in a 96-well plate (3879, Corning), and of each resulting diluted concentration, 10 μl was added per well using a multichannel pipette. All doses were run in quadruplicates divided on two plates, and the stimulation period lasted for 5 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with slight modifications. Components of the Britelite plus reporter kit and Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; 14040091, Gibco) were equilibrated to room temperature for 1 hour before use. The Britelite plus substrate was dissolved in the kit’s substrate buffer solution, gently mixed by inverting the container to ensure a clear homogeneous solution, incubated for 5 min at room temperature, followed by addition of an equal volume of DPBS. Upon completion of the stimulation period, medium was carefully removed from the cells using vacuum aspiration, and 200 μl of Britelite plus substrate mixture was added to each well of the 96-well plate. Plates were then protected from light with aluminum foil and were gently shaken for 2 min at room temperature before the plates were read using an EnVision plate reader operating in luminescence mode.

Potency (EC50) was calculated using a four parameter logistic fit, Y = A + (B –A)/(1 + 10(log10(EC50)–log10(C))*k), where A is curve bottom, B is curve top, k is slope (Hill coefficient), and C is concentration of wild-type or mutant NRTN. EC50 refers to half-maximal effective concentrations of protein in receptor activation. pEC50 = log(1/EC50) values were reported as mean ± SE with the number of experiments n = 3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Rowlinson and A. Hoyle for help with RET peptide mapping, T. M. de Oliveira for preliminary cryo-EM data collection, M. Castaldo for the production of TEV protease, and L. Öster Landgren for helpful discussions. We would also like to thank G. Holdgate and R. J. Sheppard for critical reading of the manuscript and A. Gunnarsson for help with figures. The data were collected at the Cryo-EM Swedish National Facility funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg, Family Erling Persson, and Kempe Foundations. We thank M. Carroni, M. de la Rosa Trevin, J. Conrad, and S. Fleischmann for the smooth running of the facility. We apologize to colleagues whose work was not explicitly acknowledged in this article because of the strict limitation on the number of references that can be cited. Funding: This work was supported by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (FFL15:0325), Ragnar Söderberg Foundation (M44/16), Swedish Research Council (NT_2015-04107), Cancerfonden (2017/1041), European Research Council (ERC-2018-StG-805230), and FEBS Long-Term Fellowship (to S.A.). J.M.B. is a fellow of the AstraZeneca post-doc programme. Author contributions: J.M.B., R.R., and J.S. designed the study. J.M.B. purified the proteins and performed the mutational analysis. J.M.B. and E.G. analyzed the protein complexes. S.D. produced the reporter gene data. G.D. set up the SPR assay. J.M.B. and S.A. prepared cryo-samples and optimized conditions. A.A. provided access to cryo-EM and supervised data collection and processing. S.A. collected and processed the cryo-EM data. J.M.B. and S.A. built and refined the model. J.M.B., S.A., A.A., and J.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, discussed the results, and contributed to the final manuscript. A.A. and J.S. organized the collaboration. Competing interests: J.M.B., G.D., R.R., E.G., S.D., and J. S. were employed by AstraZeneca when producing the data presented in this manuscript. All other authors declare that they have no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with accession code EMD-0026. The atomic model has been deposited in the PDB under accession code 6GL7.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaau4202/DC1

Fig. S1. SEC-MALS of the wild-type extracellular signaling complex.

Fig. S2. Cryo-EM data processing.

Fig. S3. RETECD glycosylations.

Fig. S4. SEC of the heterohexameric complex and its components.

Fig. S5. Biophysical analysis of complex formation.

Fig. S6. Related GFL-GFRα crystal structures display varying angles of GFRα positions in relation to the GFL center.

Table S1. Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Runeberg-Roos P., Saarma M., Neurotrophic factor receptor RET: Structure, cell biology, and inherited diseases. Ann. Med. 39, 572–580 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Airaksinen M. S., Saarma M., The GDNF family: Signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 383–394 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu J.-Y., Crawley S., Chen M., Ayupova D. A., Lindhout D. A., Higbee J., Kutach A., Joo W., Gao Z., Fu D., To C., Mondal K., Li B., Kekatpure A., Wang M., Laird T., Horner G., Chan J., McEntee M., Lopez M., Lakshminarasimhan D., White A., Wang S.-P., Yao J., Yie J., Matern H., Solloway M., Haldankar R., Parsons T., Tang J., Shen W. D., Alice Chen Y., Tian H., Allan B. B., Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature 550, 255–259 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullican S. E., Lin-Schmidt X., Chin C. N., Chavez J. A., Furman J. L., Armstrong A. A., Beck S. C., South V. J., Dinh T. Q., Cash-Mason T. D., Cavanaugh C. R., Nelson S., Huang C., Hunter M. J., Rangwala S. M., GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and the ligand promotes weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Nat. Med. 23, 1150–1157 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groot J. W. B., Links T. P., Plukker J. T. M., Lips C. J. M., Hofstra R. M. W., RET as a diagnostic and therapeutic target in sporadic and hereditary endocrine tumors. Endocr. Rev. 27, 535–560 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibáñez C. F., Structure and physiology of the RET receptor tyrosine kinase. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a009134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulligan L. M., RET revisited: Expanding the oncogenic portfolio. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 173–186 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlomagno F., de Vita G., Berlingieri M. T., de Franciscis V., Melillo R. M., Colantuoni V., Kraus M. H., Di Fiore P. P., Fusco A., Santoro M., Molecular heterogeneity of RET loss of function in Hirschsprung’s disease. EMBO J. 15, 2717–2725 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edery P., Eng C., Munnich A., Lyonnet S., Ret in human development and oncogenesis. Bioessays 19, 389–395 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romei C., Fugazzola L., Puxeddu E., Frasca F., Viola D., Muzza M., Moretti S., Luisa Nicolosi M., Giani C., Cirello V., Avenia N., Rossi S., Vitti P., Pinchera A., Elisei R., Modifications in the papillary thyroid cancer gene profile over the last 15 years. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E1758–E1765 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horger B. A., Nishimura M. C., Armanini M. P., Wang L. C., Poulsen K. T., Rosenblad C., Kirik D., Moffat B., Simmons L., Johnson E. Jr., Milbrandt J., Rosenthal A., Bjorklund A., Vandlen R. A., Hynes M. A., Phillips H. S., Neurturin exerts potent actions on survival and function of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 18, 4929–4937 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks W. J. Jr., Bartus R. T., Siffert J., Davis C. S., Lozano A., Boulis N., Vitek J., Stacy M., Turner D., Verhagen L., Bakay R., Watts R., Guthrie B., Jankovic J., Simpson R., Tagliati M., Alterman R., Stern M., Baltuch G., Starr P. A., Larson P. S., Ostrem J. L., Nutt J., Kieburtz K., Kordower J. H., Olanow C. W., Gene delivery of AAV2-neurturin for Parkinson’s disease: A double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 9, 1164–1172 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandmark J., Dahl G., Öster L., Xu B., Johansson P., Akerud T., Aagaard A., Davidsson P., Bigalke J. M., Winzell M. S., Rainey G. J., Roth R. G., Structure and biophysical characterization of the human full-length neurturin–GFRα2 complex: A role for heparan sulfate in signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 5492–5508 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotzbauer P. T., Lampe P. A., Heuckeroth R. O., Golden J. P., Creedon D. J., Johnson Jr. E. M., Milbrandt J., Neurturin, a relative of glial-cell-line-derived neurotrophic factor. Nature 384, 467–470 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlee S., Carmillo P., Whitty A., Quantitative analysis of the activation mechanism of the multicomponent growth-factor receptor Ret. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 636–644 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anders J., Kjær S., Ibáñez C. F., Molecular modeling of the extracellular domain of the RET receptor tyrosine kinase reveals multiple cadherin-like domains and a calcium-binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35808–35817 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kjær S., Hanrahan S., Totty N., McDonald N. Q., Mammal-restricted elements predispose human RET to folding impairment by HSCR mutations. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 726–731 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman K. M., Kjær S., Beuron F., Knowles P. P., Nawrotek A., Burns E. M., Purkiss A. G., George R., Santoro M., Morris E. P., McDonald N. Q., RET recognition of GDNF-GFRα1 ligand by a composite binding site promotes membrane-proximal self-association. Cell Rep. 8, 1894–1904 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan Y. Z., Baldwin P. R., Davis J. H., Williamson J. R., Potter C. S., Carragher B., Lyumkis D., Addressing preferred specimen orientation in single-particle cryo-EM through tilting. Nat. Methods 14, 793–796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K., Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E., UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott R. P., Ibáñez C. F., Determinants of ligand binding specificity in the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor family receptor αs. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1450–1458 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krissinel E., Henrick K., Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kjær S., Ibáñez C. F., Identification of a surface for binding to the GDNF-GFRα1 complex in the first cadherin-like domain of RET. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47898–47904 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cik M., Masure S., Lesage A. S., van der Linden I., van Gompel P., Pangalos M. N., Gordon R. D., Leysen J. E., Binding of GDNF and neurturin to human GDNF family receptor alpha 1 and 2. Influence of cRET and cooperative interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27505–27512 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka M., Xiao H., Hirata Y., Kiuchi K., A rapid assay for glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and neurturin based on transfection of cells with tyrosine hydroxylase promoter-luciferase construct. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 11, 119–122 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacheco M. C., Multiple endocrine neoplasia: A genetically diverse group of familial tumor syndromes. J. Pediatr. Genet. 5, 89–97 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulligan L. M., Eng C., Healey C. S., Clayton D., Kwok J. B. J., Gardner E., Ponder M. A., Frilling A., Jackson C. E., Lehnert H., Neumann H. P. H., Thibodeau S. N., Ponder B. A. J., Specific mutations of the RET proto-oncogene are related to disease phenotype in MEN 2A and FMTC. Nat. Genet. 6, 70–74 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santoro M., Carlomagno F., Romano A., Bottaro D. P., Dathan N. A., Grieco M., Fusco A., Vecchio G., Matoskova B., Kraus M. H., Activation of RET as a dominant transforming gene by germline mutations of MEN2A and MEN2B. Science 267, 381–383 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asai N., Iwashita T., Matsuyama M., Takahashi M., Mechanism of activation of the ret proto-oncogene by multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1613–1619 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parkash V., Goldman A., Comparison of GFL-GFRα complexes: Further evidence relating GFL bend angle to RET signalling. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 65, 551–558 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X., Baloh R. H., Milbrandt J., Garcia K. C., Structure of artemin complexed with its receptor GFRα3: Convergent recognition of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factors. Structure 14, 1083–1092 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkash V., Leppänen V. M., Virtanen H., Jurvansuu J. M., Bespalov M. M., Sidorova Y. A., Runeberg-Roos P., Saarma M., Goldman A., The structure of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor-coreceptor complex: Insights into RET signaling and heparin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35164–35172 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plaza-Menacho I., Barnouin K., Goodman K., Martínez-Torres R. J., Borg A., Murray-Rust J., Mouilleron S., Knowles P., McDonald N. Q., Oncogenic RET kinase domain mutations perturb the autophosphorylation trajectory by enhancing substrate presentation in trans. Mol. Cell 53, 738–751 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng S. Q., Palovcak E., Armache J.-P., Verba K. A., Cheng Y., Agard D. A., MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang K., Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimanius D., Forsberg B. O., Scheres S. H. W., Lindahl E., Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. eLife 5, e18722 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S., McMullan G., Faruqi A. R., Murshudov G. N., Short J. M., Scheres S. H. W., Henderson R., High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy 135, 24–35 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenthal P. B., Henderson R., Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang R. Y.-R., Song Y., Barad B. A., Cheng Y., Fraser J. S., DiMaio F., Automated structure refinement of macromolecular assemblies from cryo-EM maps using Rosetta. eLife 5, e17219 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaau4202/DC1

Fig. S1. SEC-MALS of the wild-type extracellular signaling complex.

Fig. S2. Cryo-EM data processing.

Fig. S3. RETECD glycosylations.

Fig. S4. SEC of the heterohexameric complex and its components.

Fig. S5. Biophysical analysis of complex formation.

Fig. S6. Related GFL-GFRα crystal structures display varying angles of GFRα positions in relation to the GFL center.

Table S1. Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics.