How do networks respond to fluctuating inputs?—Localized? Homogeneous? Resonant?

Abstract

Across physics, biology, and engineering, the collective dynamics of oscillatory networks often evolve into self-organized operating states. How such networks respond to external fluctuating signals fundamentally underlies their function, yet is not well understood. Here, we present a theory of dynamic network response patterns and reveal how distributed resonance patterns emerge in oscillatory networks once the dynamics of the oscillatory units become more than one-dimensional. The network resonances are topology specific and emerge at an intermediate frequency content of the input signals, between global yet homogeneous responses at low frequencies and localized responses at high frequencies. Our analysis reveals why these patterns arise and where in the network they are most prominent. These results may thus provide general theoretical insights into how fluctuating signals induce response patterns in networked systems and simultaneously help to develop practical guiding principles for real-world network design and control.

INTRODUCTION

Collective oscillatory network dynamics prevail in natural and technological systems alike, including neural and gene regulatory circuits, communication networks, and AC power grids, among others (1–8). A robust function is essential for all of these systems and relies on how their collective dynamics self-organize and respond to external signals. For example, modern power grids are driven dynamically by predictable or random signals, e.g., the fluctuating power feed-in from renewable energy sources, changes in consumer behavior on many time scales, power trading, and failures of infrastructures, all of which cause fluctuations in grid frequency in a nontrivial, distributed way (9). Human brain circuits, as functionally and structurally connected oscillatory networks exposed to external stimuli, exhibit complex activity patterns in a wide frequency band extending up to five orders of magnitude (10, 11). The dynamics of all oscillatory systems essentially underlie system functions, and all are externally driven by planned interference signals, random fluctuations, unit or link failures, etc. Yet, it is not well known how oscillatory network systems respond to such perturbations.

To analyze, understand, and predict the dynamics of coupled oscillators, networks of phase oscillators such as the paradigmatic Kuramoto model are commonly used across fields (12–15). Phase oscillator systems are preferred as generic models because they are simple to simulate, partly analytically accessible, and exhibit a wide range of collective dynamical phenomena observed in oscillatory systems, including synchronization and phase locking, heteroclinic switching dynamics, collective irregular activity, metastable synchronized states, and chimera states (16–21). In neuroscience, Kuramoto oscillator networks capture some basic mechanisms underlying cortical oscillations (15) and frequency-specific correlation patterns in connectome network from encephalographic recordings (22, 23). Some knowledge about how such networks respond to external driving signals is already established. For instance, regularly and sparsely connected networks of phase oscillators exhibit two response regimes that depend on the frequency content of the driving signals (24, 25). At low driving frequencies, the entire system dynamically responds homogeneously, i.e., all oscillators respond essentially identically. At high frequencies, the dynamical responses are localized on the network (25) and response amplitudes decay with distance, similar to the findings for chains with single, constantly driven pacemaker units (26). For the second-order Kuramoto model, the network response to a local and static perturbation may be localized or delocalized depending on network topology and other parameters (27, 28). However, an overarching theory of how networks respond systemically to dynamic, fluctuating inputs is missing to date such that the range of possible response patterns and the precise mechanisms underlying them are unknown in general, and predicting them remains generally hard if not impossible.

In this article, we develop a theory of dynamic response patterns for oscillatory networks driven by fluctuating inputs. Evaluating a network-wide linear response theory as an explicit function of frequency content of the fluctuating signals, the network’s interaction topology, and the exact location of driving and response nodes, we uncover complex distributed resonance patterns in oscillatory networks with two-dimensional unit dynamics, which are absent in standard phase oscillatory networks with one-dimensional units. These network resonances emerge at intermediate frequency content of the input signals, between global yet homogeneous responses at low frequencies and localized responses at high frequencies (Fig. 1). Resonant responses may be an order of magnitude (greater than 10 times in our examples) larger than static responses that occur in the limit of zero frequencies in the identical network. The theory furthermore explicates the origin and scaling of the localized as well as the homogeneous response patterns present, explaining and generalizing previous works (24–27). The finding and the explanation of the emergence of distributed resonance patterns together with the unifying theory we derive offer explanatory and predictive power across fluctuation-driven systems in nature and engineering.

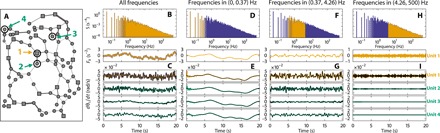

Fig. 1. Fluctuation-induced dynamic response patterns.

A sample network (A) driven by Brownian noise (B) at a single unit k = 1 exhibiting (C) complex dynamic response patterns that nonlinearly vary with frequency content of the input signal (D, F, and H) as well as with graph-theoretic distance between the input and the response unit (E, G, and I). Three response classes emerge: homogeneous responses at low frequencies (D and E), spatiotemporally irregular patterns at intermediate frequencies (F and G), and localized responses at high frequencies (H and I). To identify frequency regimes, we selected specific frequency bands [yellow in (D), (F), and (H)] from the spectrum of the original noise realization (B), and all others are displayed in purple. (C), (E), (G), and (I) display the time series of driving signal at unit k = 1 (top) and the response in the phase velocities of the units i ∈ {1, …,4} (bottom). In (C), (E), (G), and (I), the time series of the band-filtered signal are displayed together with the responses (yellow for unit 1 and green for units 2 to 4). Our theory (Eq. 5) (thin black lines) well predicts the system responses obtained from direct numerical simulations. (For details of further settings, see Materials and Methods.)

RESULTS

Model class

Consider a network of N units i ∈ {1, …, N} with dynamics

| (1) |

of phase angles θi(t) and phase velocities dθi(t)/dt at time t. Here, Ωi is the natural frequency (or acceleration) of unit i, and the units interact with coupling strengths Kij = Kji ≥ 0 via a coupling function g(⋅). Core parameters αi and βi in this model class set the relative influences of the rates of change of the phase angles and those of the phase velocities. The phenomena presented below for homogeneous αi ≡ α and βi ≡ β stay qualitatively the same for inhomogeneous systems (see section S1.4). The model class (Eq. 1) generalizes standard phase oscillator networks (13, 14) that are recovered for β = 0. Taking generically both α, β > 0 and g(⋅) = sin(⋅) yields coupled second-order Kuramoto models characterizing AC power grids, the swing equation on networks (5, 6, 29), on which we focus in the main part of this article. For such systems, θi(t) describes the mechanical angle of a synchronous machine relative to a reference frame rotating at the nominal grid reference frequency of, e.g., 2π × 50 Hz in Europe including the United Kingdom [see (5, 6) for details]. Normal stationary operation of a grid is given by a phase-locked state, where Eq. 1 exhibits a fixed vector of relative phases in the absence of any fluctuations [Fi(t) ≡ 0]. The functions Fi(t) represent the fluctuations in the production and consumption at unit i and together constitute a high-dimensional, distributed dynamic driving signal to the network. How does the network collectively respond to such dynamic signals?

Fluctuation-induced dynamic network responses

Observing the distributed network responses induced by a single local signal, Fi(t) ∼ δik, already poses puzzles about how the responses depend on the driving and the response unit on the network topology and on the frequency content of the signal, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Specifically, responses to low-frequency inputs appear to be dynamic in time yet homogeneous across the network (Fig. 1, D and E), and responses to high-frequency inputs seem to be localized (Fig. 1, H and I), whereas at intermediate frequencies, responses appear to be irregular in time and across units (Fig. 1, F and G), with severe consequences for the entire collective response pattern (compare Fig. 1, B and C).

To gain analytic insights and thereby intuition about such dynamic response patterns, we start by focusing on the responses generated at one fixed (but arbitrary) unit k by signals of fixed (arbitrary) frequencies ω and develop a linear response theory expanding in the amplitudes of the response signals into Fourier modes. In a second step, we consider more complex, distributed, and nonperiodic input signals below. Taking Fi(t) = εδikei(ωt + φ) and expanding the phase responses to first order in the signal amplitude ε, we obtain

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

denotes the oscillatory response at unit i of amplitude and phase . ηi = η ≠ 0 is an overall homogeneous phase shift that results from the dynamics of the average phase (see section S1.2) and emerges despite zero average input. For each input frequency ω, a matrix equation

| (4) |

thus describes the network response vector as a function of time. The network response vector depends on the perturbation site k, the perturbation vector F(k) with only one nonzero component , parameters β and α, and a weighted graph Laplacian matrix ℒ with elements for i ≠ j and . As ℒ is real and symmetric, its N eigenvalues are real, positive in normal operating states where for all edges (i, j). Its eigenvalues are ordered as λ[N−1] > ⋯ > λ[1] > λ[0] = 0, and its eigenvectors {v[0], ⋯, v[N−1]} form an orthogonal basis. The response vector

| (5) |

thus provides a general first-order prediction for the induced response patterns across all connected network topologies [compare (30)].

After a transient time set by the intrinsic dissipation time scale 1/α, this time-dependent vector function (Eq. 5), integrated across the signal’s frequency content, well predicts the dynamic response patterns of the entire network, see, e.g., Fig. 1. We emphasize that the prediction (Eq. 5) immediately generalizes to all network systems described by (Eq. 1) for arbitrary antisymmetric coupling function g(θj − θi). The asymmetry of g(. ) ensures a real and symmetric Laplacian matrix and thus the orthogonality of Laplacian eigenvectors.

Emergence of distributed resonance patterns

The network response theory presented above provides an analytical expression of steady nodal responses (Eq. 5), thus paving the way to a deeper understanding of the emergent complex response patterns across the network. How does this response theory predict the different response regimes observed (Fig. 1)? More specifically—How can we explicitly extract the dependences of the network response patterns on the frequency of the driving signal, on the network interaction topology, and on the graph-theoretic distance between driving and response units? To reveal more detailed insights, we systematically analyze the response strength of phase velocities dθi(t)/dt to a driving signal at unit k across many orders of magnitude of the frequency and for all response units i in a network. In this section, we assume β = 1 without loss of generality.

Such responses in phase velocities reflect deviations of the units’ frequencies of power grids from their nominal value 2π × 50 Hz and are, thus, more directly relevant than deviations in the phase angles themselves. Graphing the response strengths

| (6) |

relative to their low-frequency limit clearly indicates the three frequency regimes of characteristic responses (see Fig. 2A).

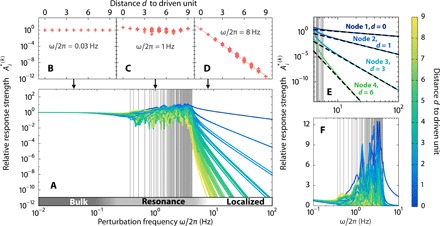

Fig. 2. Emergence of resonances and prediction of distinct network responses.

(A) The relative response strength of each unit in the fluctuation-driven network illustrated in Fig. 1A versus the signal frequency ω, color coded by the graph-theoretic distance d from the driven to the responding unit. The eigenfrequencies are indicated by gray vertical lines, and the three regimes of homogeneous bulk responses, heterogeneous resonant responses, and localized responses by the gray-level gradient bar at the bottom. (B to D) The relative response strengths characteristically depend on graph-theoretic distance, shown for individual frequencies representative for each of the three regimes. (E) In the localized regime, the response amplitudes for units 1 to 4 (marked in Fig. 1A) are well approximated by the analytic prediction (dashed lines) (Eq. 8). (F) Relative response strengths (plotted on linear scale) at resonance peaks may be an order of magnitude (here up to 12 times) larger than in the static response limit of ω → 0.

Dynamic resonance patterns emerge if the signal frequencies ω are of the same order of magnitude as the eigenfrequencies (see section S2.1)

| (7) |

The system responds with a distributed, network- and frequency-specific pattern given by Eq. 5 (Fig. 2, A, C, and F). Network resonance patterns are typically heterogeneous, exhibiting no monotonicity in frequency or with respect to the topological distance between the signal and the response unit. In contrast to resonance phenomena in low-dimensional oscillatory systems common in physics and nonlinear dynamics, the response patterns are node specific in a highly nontrivial way. Depending on an overlap factor of the responding node i with the driven node k in eigenmode ℓ, the contribution from the various eigenmodes can be positive, negative, or zero, which leads to different canceling or accumulating total responses for each frequency ω. The overlap factor acts as a node-specific weight in the eigenvector superposition, thus intuitively explaining the complex distributed dynamic response patterns. The response amplitude at resonance peaks may be an order of magnitude larger than for static responses appearing in the limit of ω → 0 (cf. Fig. 2F).

For frequencies substantially below the eigenfrequencies , all units exhibit similar response strengths, in particular independent of the topological distance between signal input and response sites (Fig. 2, A and B). At the low-frequency limit ω → 0, approaches Nα, a constant containing only intrinsic network parameters, not encoding any topology dependence. This explains the observation of homogeneous responses in Fig. 1 (D and E).

For sufficiently large driving frequencies , the response strengths decay as a power law with frequency. This decay is essentially exponential over the topological distance between signal input and unit response sites (Fig. 2, A and D). Writing the response amplitudes as rational functions of ω, with as coefficients of ω2j in the numerator of (see section S2.1.3), we obtain the first nonzero term with the highest power of ω in the numerator to be , where d ≔ d(k, i) is the topological distance between the driving unit k and the responding one i. The highest power ω4N appearing in the denominator, thus, yields the exact asymptotic expansion

| (8) |

as ω → ∞ via definition (Eq. 6). Here, the frequency dependence is encoded solely in the term ω−2d−1. The topological distance d appears explicitly twice, and encodes the overall topological properties of the network as well as the identity of the driving and the responding nodes. This result (Eq. 8) is based on exact zeros of lower-order coefficients (see section S2.1.3 for a detailed derivation) that appear because the relevant matrix element of the m-th power of the Laplacian is zero, (ℒm)ki = 0, if m < d(k, i) as there exists no path from k to i of length smaller than d(k, i). Consequently, for any given frequency in this regime, the response strengths decay approximately exponentially with the distance.

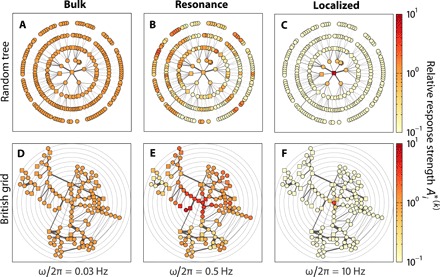

We emphasize that the above analysis about the three regimes of response patterns holds without any assumptions on the network topology, and thus is general for arbitrary interaction structures. See Fig. 3 for an illustration of the generality of the response regimes across different networks.

Fig. 3. Generality of response patterns.

For two exemplary networks, the response patterns for three signals of frequencies representing the three response regimes are indicated by their relative response strengths (color coded). Response patterns for (A) to (C), a random tree with N = 264, and (D) to (F), the topology of the British high-voltage transmission grid with N = 120, both reordered according to graph-theoretic distance from site of driving unit. For both networks, the driven unit is placed at the center with all units displayed on circles with their radii proportional to topological distance (gray concentric rings) in (D) to (F).

Fluctuation-induced distributed resonances

So far, we have systematically studied the patterns of network responses to trigonometric, sufficiently weak fluctuating signals affecting just one unit in the network. What can we say about the dynamic response patterns in networks with stronger, more irregular, and more distributed driving signals?

For input signals that are both distributed across the network and contain a broad range of frequency components (ω > 0), the linear response theory predicts the units’ responses as a linear superposition across input locations and frequencies via Eq. 5. Specifically, the phase velocity at unit i reads (see section S3)

| (9) |

where κ denotes the set of all units driven by fluctuating signals and n, k labels the dominant Fourier modes with nonzero frequencies at each such unit k. The constant drift speed results from the zero-frequency component with magnitude ε0,k in the signal at node k.

Generically, our theory (Eq. 9) has strong predictive power for all combinations of differently fluctuating inputs distributed across the network (see Fig. 4 and more details in Materials and Methods). Moreover, the eigenvector-based overlap factor in (Eq. 9) clearly demonstrates how frequency components in the driving signal that are close to the eigenfrequencies induce network-wide resonances in a specific, highly topology-dependent way.

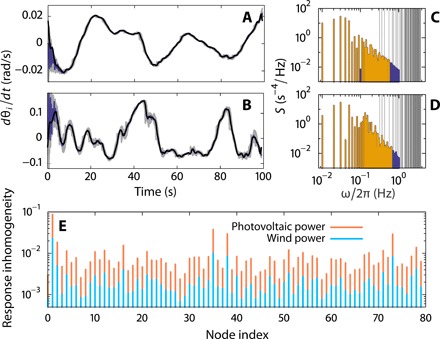

Fig. 4. Predicting response patterns of fluctuation-driven networks.

(A) A noisy signal Fi (purple) at one unit and (B) frequency response dθi/dt at another unit in the network (Fig. 1A), with every unit driven by independent Brownian noise. (B) Response prediction (black) is based on 50 dominant Fourier modes of the signal [reconstructing the yellow time series in (A)] at each unit, which, after a transient stage, is very close to the numerical response (purple) to the original signals. (C) Prediction error E (for definition, see Materials and Methods) decreases exponentially with the number of selected Fourier modes. (D) Linear response theory well predicts responses until the maximum line load exceeds 95% (line load Lij ≔ ∣sin(θj − θi)∣), i.e., the system is almost fully loaded at the operating point.

To illustrate how distributed network resonances are induced by a noisy fluctuation signal due to its resonant frequency components, we computed the response time series for a power grid model network with the topology used for Fig. 1A. The fluctuating signals were experimentally recorded from renewable energy sources. The results indicate similarities and notable differences between the responses to the recordings from photovoltaic and wind power sources. Specifically, we find that for both time series samples, fluctuations in wind power and fluctuations in the power from a photovoltaic panel (see Materials and Methods), predictions are highly accurate after a transient time (Fig. 5, A and B). In both sample time series of power fluctuation, the low-frequency components are dominant (Fig. 5, C and D) and induce low-frequency fluctuations that are homogeneous across the network (Fig. 5, A and B). In addition, the stronger and faster input fluctuations in photovoltaic power generate responses that are highly precise in time yet more inhomogeneous across the network (Fig. 5, B, D, and E). This phenomenon originates from the resonances induced by the fluctuation signal: The Fourier spectrum of the photovoltaic power fluctuation contains relatively stronger frequencies close to the resonance frequencies than the Fourier spectrum of the wind power fluctuation (see Fig. 5, C and D, Materials and Methods, and section S3.2).

Fig. 5. Frequency resonances in power grids induced by wind and photovoltaic power fluctuations.

(A and B) Response time series of grid frequency in the network (Fig. 1A) for fluctuating power input signals (A) from wind and (B) from photovoltaic panels, with (C) and (D) as the respective power spectral density S(ω). One response time series is highlighted in purple (analytic prediction in black) and of all other units in gray. The prediction is based on 50 dominant Fourier modes of the signal, highlighted in yellow in (C) and (D). The gray vertical lines indicate the system’s eigenfrequencies. (E) The photovoltaic power fluctuations with stronger higher-frequency components induce greater nodal response inhomogeneity (for definition, see Materials and Methods) than the wind power fluctuations.

DISCUSSION

To conclude, we established a theory of dynamic response patterns in fluctuation-driven oscillatory network systems by systematically analyzing the response patterns in every dynamical range of the signal’s frequency content. We revealed the emergence of the distributed resonance patterns in the intermediate frequency regime and demonstrated that they result from the externally driven second dynamic variable of individual oscillators, which are known to be absent in Kuramoto oscillator systems (24, 25). Resonance patterns are topology dependent, heterogeneous, nonlinear, and nonmonotonic in distance. For high- and low-frequency regimes, we analytically derived the generic response patterns, i.e., the homogeneous patterns at low frequencies and the localized patterns at high frequencies, by rigorously extracting the dependence of the response on distance, providing solid theoretical support and broad generalization for previous works (24–27).

The reported findings on network response patterns exhibit a number of implications for the operation and control of real-world network systems in biology and engineering. For the example of power grids, it is often believed that the AC frequency is homogeneous across the entire interconnected power system, thus the notion “grid frequency” in power grid literature [e.g., (31)]. In strong contrast, our results demonstrate that the frequency responses are indeed highly heterogeneous; therefore, grid frequency makes sense only in the regime of slow-changing driving signals. In particular, anomalous broad-range fluctuations of grid frequencies (9) may, in part, result from the combination of different response patterns to various input fluctuations across grid nodes. The network resonance phenomena here may moreover help to explain how external inputs induce the complex oscillation patterns in cortical networks, while the bulky slow oscillations and the localized high-frequency oscillations observed in experiments (10) are consistent with our theory.

The phenomenon of resonance was known before from complex dynamic systems if they were driven by external signals that act globally on all units. For instance, in 1981, Benzi reported that stochastic resonance may arise from global, homogeneous periodic forcing of stochastic dynamical systems (32–34). Even earlier (nonstochastic) resonance of molecular excitations was triggered by incident photons with a frequency matching the energy of an electronic transition of the molecule and was exploited in resonance Raman spectroscopy (35). Already in the 1950s, related fundamental phenomena were exploited to reveal energy spectra, e.g., of atomic nuclei (36). The work presented here demonstrates network-wide distributed resonances that emerge in oscillatory networks due to distributed fluctuations impinging distinctly on the different individual units. Previously found “resonances” in networks of (Kuramoto) phase oscillators exhibit a single response peak consistently appearing at zero frequency, independent of the network topology and the system’s natural frequencies (24, 25). In stark contrast, the resonances revealed and explained above are strongly specific to the interaction topology.

Together, our results indicate that external driving on the second dynamical dimension of an oscillator (its variable local frequency) present in the general model class (Eq. 1) induces characteristic dynamic and distributed resonance patterns strongly depending on which units are driven by fluctuations and on how the entire network is connected. The topology and the explicit distance dependence as well as the frequency dependence of the responses revealed here may not only provide a general theoretical prediction of how networks respond to distributed input fluctuations but may also find a range of useful applications. For instance, given the typical frequency content of fluctuation signals at specific units, our theory enables the identification of the most susceptible units in the network and thereby suggests dynamically motivated design constraints and the prevention or mitigation of systemic risks of functional failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Settings for Fig. 1

Random geometric topology in Fig. 1A was generated according to a growth model of power grids (37), where the cost-versus-redundancy trade-off parameter r = 0, meaning line redundancy is disregarded in the network growth. Squares represent generators with rated power inputs Ωi = 30 s−2, and disks represent consumers with power consumption Ωi = 10 s−2. Number of units N = 80. For all transmission lines, Kij = K = 100 s−2, and for all units, α = 1 s−1. The fluctuation signal was generated by the Wiener process with drift 0 and volatility 1.

Settings for Fig. 4

In Fig. 4 (C and D), to assess the quality of the prediction for phase velocity, we define the prediction error as

| (10) |

where and are the phase velocity responses obtained from the above linear response theory (Eq. 9) and direct numerical simulations, respectively. The angular brackets indicate the average over time and over all units in the network. The error bars in Fig. 4C indicate the standard deviation of prediction error across 70 realizations of noisy signals. In Fig. 4D, by proportionally amplifying the power generation and consumption Ωi with an incrementally increasing factor r: Ωi → rΩi, we systematically increased the line loads for every link (i, j) at the steady state and tested the prediction error for the same noise time series as in Fig. 4 (A and B). In the prediction, 50 dominant Fourier components were included. The data points were color coded by the maximum line load in the network under perturbation in a time interval t = 20 s. The error bars stand for the standard deviation of prediction error over the network. The time average of the prediction error for individual nodes is plotted as light gray lines.

Settings for Fig. 5

(A to D) The recordings of the fluctuating power output from renewable energy sources, wind turbines, and photovoltaic panels are obtained from and available under Reference (20) of (38). In the computation of network responses, we used a coarse-grained model of power grids, with each node representing a coherent subgrid. See section S3.2 for details of the model. In Fig. 5E, the nodal response inhomogeneity of node i is defined as the uncorrelatedness between the response time series of response at node i and the response time series 〈dθj/dt〉j averaged across the network: 1 − corr(dθi/dt, 〈dθj/dt〉j), with corr(x, y) being the normalized cross correlation between time series x and y

| (11) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Schröder and D. Manik for the insightful discussions. Funding: We gratefully acknowledge support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy EXC-2068 390729961 Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life and the Cluster of Excellence Center for Advancing Electronics at TU Dresden, the German Federal Ministry for Research and Education (BMBF grants no. 03SF0472F and 03EK3055F), and the Helmholtz Association (via the joint initiative “Energy System 2050—A Contribution of the Research Field Energy” and grant no. VH-NG-1025). The works of X.Z. were supported by the IMPRS Physics of Biological and Complex Systems, Göttingen. Author contributions: X.Z., M.T., and D.W. conceived the research. All authors contributed in discussions, and X.Z. conducted the formal analysis. X.Z. and M.T. prepared the manuscript with inputs from all authors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaav1027/DC1

Section S1. Theory of dynamic response patterns in oscillatory networks

Section S2. Frequency regimes of dynamic response patterns

Section S3. Predicting dynamic responses to irregular and distributed noises

Section S4. Limit of validity of linear response theory

Fig. S1. Estimating response strength in inhomogeneous networks.

Fig. S2. Dynamic network response patterns in three regimes.

Fig. S3. Three frequency regimes of response patterns in networks of first-order (Kuramoto) oscillators.

Fig. S4. An illustration of the frequency sampling method.

Fig. S5. Grid responses to real-world power fluctuations.

Fig. S6. Limit of validity of linear response theory under strong perturbations.

Fig. S7. Breakdown of linear response theory at the fully loaded point.

Fig. S8. Limit of validity of linear response theory in heavily loaded networks.

Movie S1. Network response to Brownian noise at one node (accompanying Fig. 1).

Movie S2. Network response to independent Brownian noise at all nodes (accompanying Fig. 4, A and B).

Movie S3. Network response to a sinusoidal signal in bulk regime (accompanying Fig. 2B).

Movie S4. Network response to a sinusoidal signal in resonance regime (accompanying Fig. 2C).

Movie S5. Network response to a sinusoidal signal in localized regime (accompanying Fig. 2D).

Movie S6. Network response to a real-world wind power fluctuation (accompanying Fig. 5A).

Movie S7. Network response to a real-world photovoltaic power fluctuation (accompanying Fig. 5B).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Strogatz S. H., Exploring complex networks. Nature 410, 268–276 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muresan R. C., Jurjuţ O. F., Moca V. V., Singer W., Nikolic D., The oscillation score: An efficient method for estimating oscillation strength in neuronal activity. J. Neurophysiol. 99, 1333–1353 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahnke S., Memmesheimer R.-M., Timme M., Oscillation-induced signal transmission and gating in neural circuits. PLOS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003940 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karzbrun E., Tayar A. M., Noireaux V., Bar-Ziv R. H., Programmable on-chip DNA compartments as artificial cells. Science 345, 829–832 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filatrella G., Nielsen A. H., Pedersen N. F., Analysis of a power grid using a Kuramoto-like model. Eur. Phys. J. B. 61, 485–491 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohden M., Sorge A., Timme M., Witthaut D., Self-organized synchronization in decentralized power grids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 064101 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motter A. E., Myers S. A., Anghel M., Nishikawa T., Spontaneous synchrony in power-grid networks. Nat. Phys. 9, 191–197 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirst C., Timme M., Battaglia D., Dynamic information routing in complex networks. Nat. Commun. 7, 11061 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schäfer B., Beck C., Aihara K., Witthaut D., Timme M., Non-Gaussian power grid frequency fluctuations characterized by Lévy-stable laws and superstatistics. Nat. Energy 3, 119–126 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buzsáki G., Draguhn A., Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science 304, 1926–1929 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrmann C. S., Murray M. M., Ionta S., Hutt A., Lefebvre J., Shaping intrinsic neural oscillations with periodic stimulation. J. Neurosci. 36, 5328–5337 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Y. Kuramoto, International Symposium on Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics (Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg, 1975), pp. 420–422. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acebrón J. A., Bonilla L. L., Vicente C. J. P., Ritort F., Spigler R., The Kuramoto model: A simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 137–185 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strogatz S. H., From Kuramoto to Crawford: Exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators. Physica D 143, 1–20 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breakspear M., Heitmann S., Daffertshofer A., Generative models of cortical oscillations: Neurobiological implications of the kuramoto model. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 190 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A. Pikovsky, M. Rosenblum, J. Kurths, Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences (Cambridge university press, 2003), vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashwin P., Borresen J., Discrete computation using a perturbed heteroclinic network. Phys. Lett. A 347, 208–214 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neves F. S., Timme M., Computation by switching in complex networks of states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 018701 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotwal T., Jiang X., Abrams D. M., Connecting the Kuramoto model and the chimera state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 264101 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niebur E., Schuster H. G., Kammen D. M., Collective frequencies and metastability in networks of limit-cycle oscillators with time delay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 2753–2756 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.C. Bick, M. Goodfellow, C. R. Laing, E. A. Martens, Understanding the dynamics of biological and neural oscillator networks through mean-field reductions: A review. arXiv:1902.05307 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Cabral J., Hugues E., Sporns O., Deco G., Role of local network oscillations in resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage 57, 130–139 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabral J., Luckhoo H., Woolrich M., Joensson M., Mohseni H., Baker A., Kringelbach M. L., Deco G., Exploring mechanisms of spontaneous functional connectivity in meg: how delayed network interactions lead to structured amplitude envelopes of band-pass filtered oscillations. Neuroimage 90, 423–435 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanette D. H., Propagation of small perturbations in synchronized oscillator networks. Europhys. Lett. 68, 356–362 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanette D. H., Disturbing synchronization: Propagation of perturbations in networks of coupled oscillators. Eur. Phys. J. B 43, 97–108 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radicchi F., Meyer-Ortmanns H., Entrainment of coupled oscillators on regular networks by pacemakers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 73, 036218 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kettemann S., Delocalization of disturbances and the stability of ac electricity grids. Phys. Rev. E 94, 062311 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.M. Wolff, P. G. Lind, P. Maass, Power grid stability under perturbation of single nodes: Effects of heterogeneity and internal nodes. arXiv:1805.02017 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.P. Kundur, N. J. Balu, M. G. Lauby, Power System Stability and Control, ser. The EPRI Power System Engineering Series (McGraw-hill New York, 1994), vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manik D., Witthaut D., Schäfer B., Matthiae M., Sorge A., Rohden M., Katifori E., Timme M., Supply networks: Instabilities without overload. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 223, 2527–2547 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Short J. A., Infield D. G., Freris L. L., Stabilization of grid frequency through dynamic demand control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 22, 1284–1293 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benzi R., Sutera A., Vulpiani A., The mechanism of stochastic resonance. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 14, L453 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiesenfeld K., Moss F., Stochastic resonance and the benefits of noise: From ice ages to crayfish and squids. Nature 373, 33 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benzi R., Stochastic resonance in complex systems. J. Stat. Mech. 2009, P01052 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiro T. G., Stein P., Resonance effects in vibrational scattering from complex molecules. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 28, 501–521 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 36.E. P. Wigner, Proceedings of the Conference on Neutron Physics by Time-of-Flight (Gatlinburg, Tenessee, USA, 1956), pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schultz P., Heitzig J., Kurths J., A random growth model for power grids and other spatially embedded infrastructure networks. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 223, 2593–2610 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anvari M., Lohmann G., Wächter M., Milan P., Lorenz E., Heinemann D., Tabar M. R. R., Peinke J., Short term fluctuations of wind and solar power systems. New J. Phys. 18, 063027 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, Zeitreihen zur Entwicklung der erneuerbaren Energien in Deutschland, Accessed: 30.10.2017, (2017); http://www.erneuerbare-energien.de/EE/Navigation/DE/Service/Erneuerbare_Energien_in_Zahlen/Zeitreihen/zeitreihen.html.

- 40.J. Machowski, J. Bialek, J. Bumby, Power System Dynamics: Stability and Control (John Wiley & Sons, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41.P. Tielens, D. Van Hertem, Grid Inertia and Frequency Control in Power Systems with High Penetration of Renewables (2012).

- 42.S. D’Arco, J. A. Suul, PowerTech (POWERTECH), 2013 (IEEE Grenoble (IEEE, 2013), pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 43.J. Schiffer, D. Goldin, J. Raisch, T. Sezi, IEEE 52nd Annual Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), 2013 (IEEE, 2013), pp. 2334–2339. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ulbig A., Borsche T. S., Andersson G., Impact of low rotational inertia on power system stability and operation. IFAC Proc. Vol. 47, 7290–7297 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 45.G. Andersson, Modelling and analysis of electric power systems. EEH-Power Systems Laboratory, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zürich, Switzerland (2008).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaav1027/DC1

Section S1. Theory of dynamic response patterns in oscillatory networks

Section S2. Frequency regimes of dynamic response patterns

Section S3. Predicting dynamic responses to irregular and distributed noises

Section S4. Limit of validity of linear response theory

Fig. S1. Estimating response strength in inhomogeneous networks.

Fig. S2. Dynamic network response patterns in three regimes.

Fig. S3. Three frequency regimes of response patterns in networks of first-order (Kuramoto) oscillators.

Fig. S4. An illustration of the frequency sampling method.

Fig. S5. Grid responses to real-world power fluctuations.

Fig. S6. Limit of validity of linear response theory under strong perturbations.

Fig. S7. Breakdown of linear response theory at the fully loaded point.

Fig. S8. Limit of validity of linear response theory in heavily loaded networks.

Movie S1. Network response to Brownian noise at one node (accompanying Fig. 1).

Movie S2. Network response to independent Brownian noise at all nodes (accompanying Fig. 4, A and B).

Movie S3. Network response to a sinusoidal signal in bulk regime (accompanying Fig. 2B).

Movie S4. Network response to a sinusoidal signal in resonance regime (accompanying Fig. 2C).

Movie S5. Network response to a sinusoidal signal in localized regime (accompanying Fig. 2D).

Movie S6. Network response to a real-world wind power fluctuation (accompanying Fig. 5A).

Movie S7. Network response to a real-world photovoltaic power fluctuation (accompanying Fig. 5B).