Abstract

As rents have risen and wages have not kept pace, housing affordability in the United States has declined over the last 15 years, impacting the housing and living arrangements of low-income families. Housing subsidies improve the housing situations of low-income families, but less than one in four eligible families receive a voucher. In this article, we analyze whether one of the largest anti-poverty programs in the United States—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—affects the housing (eviction, homelessness, and affordability) and living arrangements (doubling up, number of people in the household, and crowding) of low-income families. Using the Current Population Survey, the American Community Survey/decennial census, and the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, we employ a parameterized difference-in-differences strategy to examine whether policy-induced expansions to the EITC affect the housing and living arrangements of single mothers. Results suggest that a $1,000 increase in the EITC improves housing by reducing housing cost burdens, but it has no effect on eviction or homelessness. Increases in the EITC also reduce doubling up (living with additional, nonnuclear family adults)—in particular, doubling up in someone else’s home—and reduce three-generation/multigenerational coresidence, suggesting that mothers have a preference to live independently. We find weak evidence for a reduction in overall household size, yet the EITC does reduce household crowding. Although the EITC is not an explicit housing policy, expansions to the EITC are generally linked with improved housing outcomes for single mothers and their children.

Keywords: EITC, Housing, Living arrangements, Doubling up, Household instability

Introduction

Stable housing is crucial to the physical, emotional, and economic well-being of individuals and families (e.g., Bratt 2002; Leventhal and Newman 2010). Housing affordability in the United States has declined over the last few decades, impacting the housing and living arrangements of low-income families (Desmond 2016; Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) 2017). Housing subsidies for low-income renters, such as housing choice vouchers, are effective at improving housing outcomes (e.g., Ellen 2017), but only 24 % of the 19 million eligible households receive assistance, and wait lists for housing assistance are frequently two to three years long (Leopold et al. 2015). Understanding how other poverty-related public policies, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), might affect the housing and living arrangements of low-income families with children is of vital importance. By understanding whether the EITC affects housing outcomes, such as homelessness, affordability, and living arrangements, we can consider whether expansions to the EITC might improve the housing of low-income families.

The EITC may affect the housing of low-income families in a number of ways. First, as one of the largest cash transfer programs in the United States, it provides low-income families with cash that can be used on housing: an average of more than $3,000 for families with children (Center for Budget and Policy Priorities 2016). Second, the EITC has been shown to increase employment and long-term earnings (e.g., Dahl et al. 2009), which in turn may increase income, thus affecting housing and living arrangements. Last, the EITC is distributed as a lump sum payment, which may provide households with cash needed for a security deposit or the ability to prepay a few months of rent. Despite the EITC’s potential to positively impact housing and living arrangements, no quantitative research to date has examined this link.

Exploiting federal, state, and family size variation in the generosity of the EITC over the last three decades, we examine the effect of the EITC on housing outcomes and the living arrangements of single mothers. We use data from three sources—the Current Population Survey, the American Community Survey/decennial census, and the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study—to examine a variety of housing outcomes, employ different methodological approaches, and address data limitations in each data set. Using a parameterized difference-in-differences approach—similar to a traditional difference-in-differences analysis but allowing us to exploit variation in the many EITC policy changes over time—we study a number of housing and living arrangement outcomes that have been linked in prior research with the health and well-being of families. Specifically, we study whether expansions to the EITC affect homelessness and eviction; cost burden (share of earnings paid on rent/mortgage); and living arrangements, including doubling-up (living with additional nonnuclear family adults), multigenerational households (coresident grandparent, parent, and child), household size, being named on the lease or mortgage, and household crowding. We focus our analysis on single mothers, the primary recipients of the EITC (Tax Policy Center 2006), who are most likely to experience poor housing outcomes (JCHS 2017) and whose children may be particularly vulnerable to any detrimental impacts of housing instability (e.g., Ziol-Guest and McKenna 2014). Overall, this study broadens our understanding of how the EITC affects the housing and living arrangements of low-income families, informing future policy proposals to further expand the credit.

Background

The Earned Income Tax Credit

The EITC began in 1975 as a temporary credit (made permanent in 1978) for low-income parents, intended to offset payroll tax contributions. The credit is fully refundable, which means that households with no tax liability can still receive the credit in the form of an income tax refund. The benefit schedule has a trapezoidal structure, with benefits phasing in up to a threshold, remaining constant over some values of income (plateau), and then phasing out for earnings beyond a second threshold. Over the last few decades, there have been several expansions to the federal credit, including increases to the phase-in rate and expanded benefits for families with two or more children. In 2009, a benefit for three or more children was introduced. Between 1975 and 2016, the maximum federal EITC grew from $1,700 to $6,300 (2016 dollars).

In addition to the federal EITC, 26 states and the District of Columbia had their own EITCs as of 2016 (see Table A1, online appendix, for more detail). States with EITCs can be found in all regions of the country and across the political spectrum. Several large-population states have EITCs (e.g., New York, California, and Illinois), whereas other large-population states do not (e.g., Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania). Most state EITCs are structured as fixed percentages of the federal benefit, supplementing the credit for residents filing taxes in those states. Benefit generosity currently ranges from 3.5 % up to 43 % of the federal credit, and most state credits are refundable. States vary in when they implemented EITCs, with the earliest states implementing EITCs in the mid-1980s and the most recent states implementing policies in 2017. Several states changed the generosity of their benefits over time, most becoming more generous; however, some have also decreased generosity.

The year that a state enacted an EITC and the generosity of state EITC benefits are sources of between-state variation. Within-state variation in EITC benefits arises as states implement, expand, and reduce their programs over time. Additionally, any federal changes to the EITC also impact states that have their own EITCs, creating an additional source of between and within state variation over time. We use this federal and state variation over time to examine whether the EITC is linked to housing and living arrangements.

Why Might the EITC Affect Housing Outcomes and Living Arrangements?

We expect the EITC to affect housing and living arrangements because it increases disposable income, increases labor supply and earnings, and provides families with a lump sum payment that might be used for housing. This increased income leads to three specific hypotheses related to how the EITC might influence housing and living arrangements:

Hypothesis 1: The EITC will likely reduce homelessness and eviction/foreclosures.

Research has found that income transfers reduce homelessness/eviction (e.g., Evans et al. 2016); thus, we expect an increase in the EITC to have a similar effect. However, it is also possible that the EITC will not affect homelessness or eviction given that individuals can receive the EITC only if they are employed, and research has shown the EITC does little to assist those at the very bottom of the income distribution (below 50 % of the poverty line; Hoynes and Patel 2018). If mothers who are homeless or evicted are unemployed or have very low incomes, then expansions to the EITC may do little to reduce these severe forms of housing instability.

Hypothesis 2: The EITC should reduce the share of mothers who are cost-burdened.

The increased income from the EITC should reduce the share of mothers who report paying more than 30 % (or 50 %) of their earnings on rent/mortgage. However, if receipt of the EITC leads mothers to move into more expensive housing (say, in a better neighborhood) or move others out of their homes, then their cost burden may be unchanged or even worsen.

Hypothesis 3: Increased income from the EITC is likely to lead mothers to reduce shared living arrangements, decreasing household size and crowding.

Increased income from Social Security expansions reduced shared living arrangements (Carlson et al. 2012; Engelhardt et al. 2005), and mothers have reported that living in someone else’s home is challenging because it conflicts with their ideal sand identities (Harvey 2017). Thus, on average, we expect that the EITC will reduce shared living arrangements, especially doubling up in someone else’s home, which in turn will reduce household size and crowding. However, it is also possible that the increased income from the EITC will increase doubling up among single mothers if they end up supporting other economically disadvantaged friends and family (low-income mothers are typically embedded in homophilous networks; Smith et al. 2014).

Prior Research

Although no quantitative research has examined if the EITC is linked to housing and living arrangements, a number of studies have explored links between these outcomes and income-related policies.1 Qualitative research has suggested that low-income families rely heavily on the EITC as a means of improving housing outcomes, such as paying for security deposits or rent (Halpern-Meekin et al. 2015). A related experimental study found that individuals who were at risk of losing their homes and received cash assistance were 76 % less likely to enter a shelter compared with those who applied for aid after the funds were depleted (Evans et al. 2016). Studies of the effect of the EITC on living arrangements have examined its impact on marriage, finding small negative effects (Dickert-Conlin and Houser 2002; Herbst 2011; Michelmore 2018), but they have not analyzed other living arrangements. Related research on the effects of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) has found mixed results on living arrangements (Bitler et al. 2006). In contrast, research on Social Security expansions has generally found that increases in income result in more elderly living independently (e.g., Engelhardt et al. 2005).

An extensive literature has examined the effect of housing support policies (public housing and housing choice vouchers) on housing stability and other outcomes. Although functionally different from the EITC (in-kind, different eligibility requirements), both public housing and housing vouchers reduce housing costs, thus increasing household income to spend on other items (e.g., Jacob and Ludwig 2012; Mills et al. 2006). In general, vouchers have been linked with reduced homelessness (Gubits et al. 2016) and crowding (Carlson et al. 2012), with mixed evidence on housing quality and neighborhoods (for a review, see Ellen 2017). One study found that voucher receipt was linked with fewer adults living in the household (Carlson et al. 2012). Related evidence from a randomized housing-mobility program (Moving to Opportunity) found that moving to higher-income neighborhoods improved mental and physical health and subjective well-being (e.g., Clampet-Lundquist and Massey 2008; Katz et al. 2001; Kling et al. 2007) and mixed evidence for child well-being (e.g., Chetty et al. 2016; Ludwig et al. 2013). Last, research has found that living in a housing project is associated with less crowding and improved school outcomes (Currie and Yelowitz 2000) but also no effects on children (Jacob 2004). In sum, the literature generally suggests that subsidized housing is linked with improved housing and individual outcomes, with some exceptions.

Although no research has examined the effect of the EITC on housing outcomes, many studies have investigated its effect on related outcomes. Research has shown that the EITC increases the labor supply of single mothers (e.g., Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001), increases earnings (Dahl et al. 2009), lifts families out of poverty (Hoynes and Patel 2018), increases household savings (Jones and Michelmore 2018), reduces child neglect (Berger et al. 2017), and improves children’s education outcomes (Bastian and Michelmore 2018; Dahl and Lochner 2012). Together, this literature suggests that the EITC reduces economic uncertainty and reduces poverty, which in turn may affect housing and household well-being.

Method

Data

Data for our analyses come from three primary sources: the Current Population Survey (CPS) March Supplement, the American Community Survey (ACS)/decennial census, and the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). We discuss each source in turn.

Current Population Survey

The CPS is a nationally representative household survey conducted annually in March, gathering household income and employment information based on the prior calendar year. Each year the survey collects data from approximately 60,000 households. We use the 1990–2016 surveys, reflecting the tax years 1989 to 2015. This period captures the effect of the numerous federal expansions to the EITC in the early 1990s and the introduction of many of the state EITCs, which largely occurred after welfare reform in 1996.

We limit our sample to single mothers who are identified as the respondent and who have at least one child under the age of 19 residing in the household (n = 137,595). Although pointers help us link parents and children, we must restrict our sample to respondents to accurately ascertain other relationships in the household: for example, we cannot reliably identify multigenerational households where the mother or grandparent is not the respondent. In Table A2 in the online appendix, we show results for nonrespondents for housing outcomes. We focus on single mothers because they represent the majority of EITC recipients and federal dollars spent (Tax Policy Center 2006). Following prior research (e.g., Hoynes and Patel 2018), we further limit the sample to women aged 19–45 who have less than a college degree (n = 99,409). College-educated single mothers have far lower rates of EITC eligibility than women with less education, so they are less affected by the EITC. We also exclude women living in public housing given that public housing often places restrictions on who may coreside.2 Our final analytic sample includes 85,089 single mothers.

Respondents in the CPS are required to be the owner or the renter who is named on the lease or mortgage. As a result, when we restrict our sample to respondents to obtain accurate living arrangements, we create a sample that is somewhat more advantaged relative to those who are nonrespondents (e.g., respondents are more like to be employed than nonrespondents). To address this issue, and to examine whether the findings are robust to other data sources and methods, we supplement our CPS analysis with two additional data sets.3

ACS/Decennial Census

We also incorporate data from the 2000–2016 ACS and the 1990 decennial census (Ruggles et al. 2018).4 Although the ACS uses a household roster that also requires that we restrict to the respondent to get accurate household relationships, unlike the CPS, there is no preference for the renter/owner of note; any adult who will live (or has lived) in the household for two months or more can fill out the ACS. Thus, respondents are more likely to include both householders and subfamilies. Further, the ACS allows us to investigate how the EITC affects household crowding and cost burden, measures not available in the CPS. The ACS, however, did not exist in the 1990s, so we are unable to fully evaluate the effects of the mid-1990s federal EITC expansions using the ACS. Additional information on the ACS/census and differences between the CPS and ACS are available in the online appendix. After we make the same sample restrictions as for the CPS (except excluding public housing recipients because this information is not available), our ACS/census analytic sample includes 757,877 single mothers.

FFCWS

Because there may be concerns that the EITC changes the population of single mothers over time, we further supplement our analyses with panel data from the FFCWS, a longitudinal birth cohort study covering tax years 1998–2016.5 Mothers were interviewed at the birth of the child and at ages 1, 3, 5, 9, and 15 years old. The FFCWS oversampled nonmarital births, making it ideal for studying single mothers but also rendering it a more disadvantaged sample than the ACS or CPS. Because the FFCWS follows the same individuals over time, we conduct an individual fixed-effects analysis. This allows us to observe within-person changes in outcomes of interest as a function of EITC generosity, which also varies within person over time because of federal and state policy changes. After sample restrictions, the analytic sample includes 9,930 person-observations.

Although each data set has advantages and disadvantages, together they help us gain a better understanding of the impact of the EITC on housing and living arrangements of single mothers. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on the three samples. Despite some sampling and methodological differences between the CPS and ACS, demographic characteristics of the women in the two samples are quite similar. Mothers in the FFCWS, however, are younger, less educated, and comprise more racial minorities compared with mothers in the ACS and CPS. These differences are expected given the differences in sampling frameworks.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics: CPS, ACS, and FFCWS

| CPS | ACS | FFCWS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Characteristics | |||

| Age | 33.62 | 33.78 | 29.65 |

| (6.82) | (6.83) | (7.34) | |

| Number of children | 1.78 | 1.79 | 2.02 |

| (0.78) | (0.78) | (0.82) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.14 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.57 |

| Hispanic | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.26 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.44 |

| High school diploma | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.30 |

| Some college | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.26 |

| Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) | |||

| Average simulated EITC (in $1,000s, 2011 dollars) | 1.54 | 1.62 | 1.87 |

| (0.59) | (0.60) | (0.51) | |

| Eligible for the EITC | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.69 |

| EITC credit (in $1,000s, 2011 dollars) | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.67 |

| (1.67) | (1.66) | (1.75) | |

| Number of Observations | 85,089 | 757,977 | 9,946 |

Notes: Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. The sample is restricted to single mothers with less than a college degree and with at least one coresident child under the age of 19. The CPS and ACS are also restricted to mothers aged 19–45.

Sources: Current Population Survey (CPS) 1990–2016. Census 1990/American Community Survey (ACS) 2000–2016. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) 1998–2016.

Measures

Homelessness and Eviction

We examine homelessness and eviction because studies have found that both are associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including worse health (e.g., Burgard et al. 2012), job loss (Desmond and Gershenson 2016), and behavior problems in children (Labella et al. 2019). In the CPS, mothers who reported moving because of eviction or foreclosure in the last year are considered to have experienced foreclosure/eviction. In the FFCWS, we create binary indicators for eviction and homelessness if mothers report experiencing either in the last year.

Cost Burden

High housing costs are linked with housing instability (JCHS 2017). High cost burdens can affect neighborhood choice and other household expenditures that might be detrimental to children (Bratt 2002; JCHS 2017). Thus, we examine mother’s cost burden, or her housing affordability, using data from the ACS. We construct a measure of moderate cost burden (paying 30 % or more of pretax earnings on rent/mortgage) and a measure of severe cost burden (paying 50 % or more of pretax earnings on rent/mortgage).

Living Arrangements

We examine living arrangements, or changes in household composition (sometimes referred to as household instability; Desmond and Perkins 2016), because the composition of the household can affect family well-being. First we study doubling up, an indicator that the mother is living with a grandparent, parent/in-law, sibling, aunt/uncle, nonrelated adult, or niece/nephew over the age of 18. Following previous research (Mykyta and Macartney 2012; Pilkauskas et al. 2014), we do not consider a mother to be doubled up if she lives with any child under the age of 18 or a cohabiting partner (married mothers are excluded from our study). Although cohabitation may be a form of doubling up, the underlying motivation for living with a partner is likely quite different than living with other relatives and nonrelatives.6 We study doubling up because it is a common precursor to homelessness, it is often precipitated by a crisis that affects housing (e.g., Wright et al. 1998), and about 65 % of the children identified as homeless by school districts are living in doubled-up households (National Center for Homeless Education 2011). However, doubling up may also represent a form of social support or preference (e.g., Edin and Lein 1997; Stack 1975): families that can move in with others may avoid more extreme forms of housing instability, such as homelessness, and may save significant amounts of money on rent (Pilkauskas et al. 2014). Doubling up is assessed in all three data sets.

Second, because doubling up in someone else’s home is a less-stable living arrangement than living in one’s own home (Skobba and Goetz 2015), for the FFCWS, we use data on leases and mortgages from the Years 3–15 surveys to construct two measures: (1) an indicator of doubling up in someone else’s home, and (2) a variable that identifies whether the mother is named on the lease or mortgage.

Third, in all three data sets, we study a particular type of doubled-up household: a multigenerational household, sometimes referred to as a three-generation household. Multigenerational households are defined as those that include a single mother, her child(ren), and at least one of the child’s grandparents.7 We examine these households separately because their prevalence has increased in recent decades (Pilkauskas and Cross 2018), they are particularly common among low-income and single-mother households (Pilkauskas 2012), and multigenerational coresidence is linked with child well-being (e.g., DeLeire and Kalil 2002).

Fourth, we examine the total number of people in the household in the three data sets. In the FFCWS, we also conduct additional analyses separately examining the number of adults in the household and the number of children in the household. This is closely related to our final living arrangement measure, household crowding; crowding is associated with poorer outcomes for children (see, e.g., Evans et al. 1998), including lower graduation rates (Lopoo and London 2016). Using data from the ACS, we define household crowding as more than one person per room (excluding bathrooms).

Earned Income Tax Credit

Our main independent variable of interest is a simulated measure of average EITC generosity at the state–year–family size level. This simulated measure captures policy variation in the EITC at the federal and state level over time while eliminating variation in the EITC due to endogenous family processes, such as job loss, geographic moves, or fertility.

To construct the simulated EITC, we use a nationally representative sample of single mothers from the 1996 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).8 Using a nationally representative sample of single mothers that is independent of the sample used in our analysis reduces concerns that our sample is not representative of the population of single mothers. We inflate (deflate) the sample mothers’ earnings using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in each year between 1989 and 2015. Inflating (deflating) earnings by the CPI rather than observing changes in the income distribution over time reduces concerns that changes to the EITC may affect changes in the national income distribution of single mothers. Using National Bureau of Economic Research’s TAXSIM program (Feenberg and Coutts 1993; www.nber.org/taxsim), we calculate federal taxes for each year between 1989 and 2015. We then determine average state EITC benefits by running the national sample of single mothers through each state’s EITC laws in each year between 1989 and 2015. Calculating state EITCs using the national sample of single mothers (rather than mothers who live in that state) reduces concerns of endogeneity of state demographic characteristics with respect to state EITC benefits.

We then collapse the sample to the state–year–family size level, which produces a data set containing a measure of the average federal and state EITC a single mother can expect to receive given her state, year, and number of children (one, two, or three or more children). We then match this information to our sample of single mothers in each data source. Variation in this measure across individuals will reflect differences in policy generosity only across states, time, and family size, and not potentially endogenous changes to family income, family size, or geographic location.9

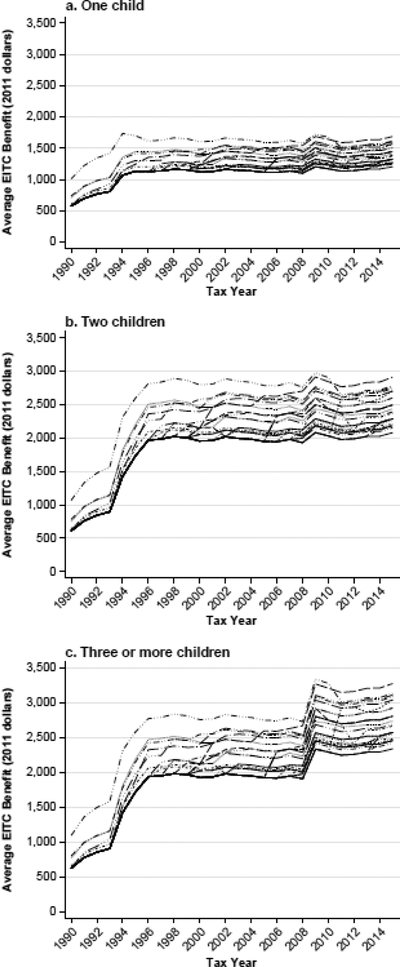

Figure 1 presents a visual depiction of the variation in the simulated EITC over time for all states by number of children that we exploit in our analyses. Panel a shows the EITC for one-child households. The difference in average EITC benefits in states that do not have their own EITCs compared with the most generous state is approximately $500, and the average household EITC (federal and state) benefit for a one-child household is about $1,100 (all dollars in 2011 real terms). Two-child households typically receive larger EITC benefits, as shown in panel b; the average two-child EITC increased from $625 in 1990 to more than $2,200 in 2015. The difference between the least generous and most generous state was also larger for two-child households, by roughly $1,000. Finally, as shown in panel c, the variation in simulated EITC benefits for households with three or more children was the same as that of two children until 2009, when the EITC was expanded for households with at least three children. This expansion produced an increase in average household EITC benefits of about $500 for families with three or more children.

Fig. 1.

Variation in simulated instrument, by state and number of children. Data are for single women aged 19–45 with at least one child under the age of 19 residing in the household. Average household state and federal EITC benefits are from 1990–2015 in 2011 dollars. Each line represents a separate state. Federal variation is shown with the bottom line in each graph. See the description of simulated EITC in the text for more details. Source: 1996 Survey of Income and Program Participation and the National Bureau of Economic Research’s TAXSIM.

Demographic and Contextual Variables

We include a number of demographic and state-year contextual measures in our analyses: respondent’s education (less than high school, high school, or some college); age; and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and other non-Hispanic race/ethnicity). We also include fixed effects for state, survey year, and number of children.10 Finally, we also include a number of state-year contextual factors that might be correlated with both housing stability and EITC generosity: specifically, the state unemployment rate, state gross domestic product (GDP), and the maximum monthly welfare benefit available for a three-person family.11 These controls are included to address concerns that implementation and expansion of state EITCs may be correlated with the economic conditions in the state, which may in turn affect housing outcomes. To further address concerns that state EITC implementation and expansions may not be independent of other state factors, we also include state-specific linear time trends.

Empirical Strategy

To investigate the relationship between EITC generosity and housing, we use a parameterized difference-in-differences approach, which is commonly used when evaluating multiple policy changes over a period (e.g., Currie and Gruber 1996; Hoynes and Patel 2018). A parameterized difference-in-differences approach is akin to that of a traditional difference-in-differences analysis, with similar assumptions, but allows for both multiple policy changes over time as well as differences in the magnitudes of each policy change. This method is useful in this context because the federal EITC was expanded at several points over our study period and affected households of different sizes differently. Additionally, several states implemented their own EITCs over this period, which also leads to larger average credits among individuals residing in those states. This approach allows us to exploit the full richness of the EITC policy landscape over the past 20 years rather than focusing on any individual policy expansion to produce easily interpretable intent-to-treat estimates of what happens to housing and living arrangements when the average EITC benefit becomes more generous.

Because households would not receive their EITC benefits in the current tax year until the following year (e.g., households would receive EITC benefits based on 2011 tax policy in 2012), we lag EITC generosity by one year. (Results using a two-year lag were similar, although smaller.) We then estimate the following reduced-form model:

| (1) |

Where Yistc represents the housing and living arrangement outcomes of interest for individual i living in state s in year t with number of children in the household c. EITCstc is the average federal and state EITC for a single mother living in state s in year t with number of children c and reflects federal and state policy changes to the EITC between 1989 and 2015. Demographic characteristics, measured at the individual level, are represented by Xistc. State-year level controls, including state-specific linear time trends, are represented by αst. Additionally, we include fixed effects for state, year, and number of children: δs, γt, and θc, respectively. All the results we discuss are robust to a Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing unless otherwise noted.12

With these controls in the model, we interpret β1 as the effect of a $1,000 increase in EITC generosity at the state–year–family size level on our measures of housing instability and living arrangements. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. Results from these analyses provide plausibly causal estimates of how increasing EITC generosity affects the housing and living arrangements of single mothers. For the FFCWS, we follow a similar strategy but include individual-level fixed effects (explained further in the online appendix).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

We begin by presenting descriptive statistics on the housing and living arrangements of single mothers in our three data sets in Table 2. In all three data sources, about two-thirds of single mothers work, with average pretax earnings of approximately $20,000 (in 2011 dollars). Single mothers in the FFCWS work and earn slightly less than the mothers in the CPS and ACS, likely because of differences in sample composition. Eviction and foreclosure are rare (2 % in the CPS and 3 % in FFCWS), and 2 % of mothers reported being homeless in the last year. Despite low levels of homelessness/eviction, many mothers reported significant cost burdens: 70 % of single mothers spend at least 30 % of their pretax earnings on housing costs, and one-half spend at least 50 % of their earnings on housing costs.

Table 2.

Sample means for employment, housing, and living arrangement outcomes: CPS, ACS, and FFCWS

| CPS | ACS | FFCWS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s Earnings/Employment | |||

| Working | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.61 |

| Annual pretax earnings (in $1,000s, 2011 dollars) | 20.09 | 20.4 | 18.78 |

| (25.53) | (22.96) | (21.31) | |

| Eviction/Homelessness | |||

| Moved because of foreclosure/evictiona | 0.02 | ||

| Evicted in last year | 0.03 | ||

| Homeless in last year | 0.02 | ||

| Cost Burden | |||

| Cost burden 30 % of mother’s earnings | 0.70 | ||

| Cost burden 50 % of mother’s earnings | 0.50 | ||

| Living Arrangements | |||

| Doubled up | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.30 |

| Living in multigenerational household | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| Doubled up in someone else’s homeb | 0.17 | ||

| Named on the lease or mortgageb | 0.74 | ||

| Number of people in the household | 3.37 | 3.41 | 4.49 |

| (1.28) | (1.31) | (1.73) | |

| Household Crowding | |||

| Crowding | 0.09 | ||

| Number of Observations | 85,089 | 757,977 | 9,946 |

Notes: Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. The sample is restricted to single mothers with less than a college degree and with at least one coresident child under the age of 19. The CPS and ACS are also restricted to mothers aged 19–45.

Sources: Current Population Survey (CPS) 1990–2016. Census 1990/American Community Survey (ACS) 2000–2016. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) 1998–2016.

Available only in the 1998–2016 CPS.

Not available in Year 1 of the FFCWS.

Doubling up is quite common among single mothers: 15 % of mothers in the CPS and 12 % in the ACS live in doubled-up households. Doubling up is twice as common among mothers in the FFCWS (30 %), likely driven by sample composition differences. Only about one-third of mothers who live in doubled-up households are living in multigenerational households in the CPS and the ACS, whereas multigenerational households account for two-thirds of all doubled-up situations among single mothers in the FFCWS. In the FFCWS, 17 % of mothers report doubling up in someone else’s home, and 74 % are named on the lease or mortgage. An average of almost 3.5 people (including the single mother) reside in the household in the CPS and the ACS, compared with about 4.5 people in the FFCWS. Finally, nearly 1 in 10 single mothers experience household crowding in the ACS.

Does the EITC Affect Employment and Earnings?

A number of studies have documented the effect of the EITC on the earnings and employment of single mothers (e.g., Dahl et al. 2009; Hoynes and Patel 2018). Thus, before presenting results for our housing outcomes of interest, we first replicate this finding in Table 3. In all but the FFCWS, we find that expansions to the EITC in the 1990s and 2000s increased the labor supply and annual earnings of single mothers. A $1,000 increase in the average EITC increases single mother’s labor supply by nearly 9 percentage points in the CPS and 6 percentage points in the ACS. In both data sets, we similarly find large increases in pretax earnings: by nearly $2,900 in the CPS and by $2,400 in the ACS. In the FFCWS, labor supply results are insignificant (2 percentage points), although positively signed, and earnings gains are about $1,400.13 The differences across data sets likely arise because of different sampling periods (FFCWS and ACS do not include the mid-1990s), types of samples (FFCWS lacks complete coverage of all states, is an urban sample, and is demographically different from the ACS/CPS), and identification strategy (FFCWS imposes individual fixed effects, whereas the ACS and CPS rely on cross-sectional data). Nonetheless, that we find positive effects on employment and earnings across the data sets helps provide confidence in the validity of our approach.

Table 3.

Effect of the EITC on employment and earnings

| CPS | ACS | FFCWS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worked Last Week | 0.087*** | 0.060*** | 0.019 |

| (0.01) | (0.005) | (0.015) | |

| Annual Pretax Earnings (in $1,000s, 2011 dollars) | 2.877*** | 2.386*** | 1.396* |

| (0.353) | (0.252) | (0.653) | |

| Number of Observations | 85,089 | 757,977 | 9,928 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses. Coefficients represent the effect of a $1,000 increase in the simulated EITC benefit on outcomes. The CPS/ACS models include demographic and state contextual characteristics; state, year, and number of child fixed effects; and state-specific time trends. FFCWS models include demographic and state contextual characteristics, year, and individual fixed effects. Each cell represents a separate regression. The sample is restricted to single mothers with less than a college degree and with at least one coresident child under the age of 19. The CPS and ACS are also restricted to mothers aged 19–45. Single mothers residing in public housing are excluded from the CPS and FFCWS.

Sources: Current Population Survey (CPS) 1990–2016. Census 1990/American Community Survey 2000–2016. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) 1998–2016.

p < .05;

p < .001

Does the EITC Affect Housing Outcomes?

Next, we turn to results, shown in Table 4, for our housing outcomes: eviction, homelessness, and cost burden. We present results from all three data sources, although not all outcomes are available in each data source.

Table 4.

Effect of the EITC on eviction, homelessness, and housing affordability

| CPS | ACS | FFCWS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eviction/Homelessness | |||

| Moved because of foreclosure/evictiona | −0.001 | ||

| (0.007) | |||

| Evicted in last year | −0.006 | ||

| (0.006) | |||

| Homeless in last year | −0.006 | ||

| (0.005) | |||

| Cost Burden | |||

| Cost burden 30 % mother’s earnings | −0.039*** | ||

| (0.004) | |||

| Cost burden 50 % mother’s earnings | −0.052*** | ||

| (0.005) | |||

| Number of Observations | 85,089 | 757,977 | 9,928 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses. Coefficients represent the effect of a $1,000 increase in the simulated EITC benefit on outcomes. The CPS and ACS models include demographic and state contextual characteristics; state, year, and number of child fixed effects; and state-specific time trends. The FFCWS models include demographic and state contextual characteristics, year, and individual fixed effects. Each cell represents a separate regression. The sample is restricted to single mothers with less than a college degree and with at least one coresident child under the age of 19. The CPS and ACS are also restricted to mothers aged 19–45. Single mothers residing in public housing are excluded from the CPS and FFCWS.

Sources: Current Population Survey (CPS), 1990–2016. Census 1990/American Community Survey, 2000–2016. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), 1998–2016.

Available only in the 1998–2016 CPS.

p < .001

In Hypothesis 1, we postulate that the EITC will decrease homelessness and eviction, yet we find no evidence to support this hypothesis. We find no significant relationship between EITC generosity and any of our eviction/foreclosure or homelessness measures in either the CPS or the FFCWS. As noted in the discussion of the hypotheses, although income transfers reduce homelessness (e.g., Evans et al. 2016), the lack of support for Hypothesis 1 may be explained by the fact that the EITC assists only those mothers who are employed but does little to help those in deep poverty (Hoynes and Patel 2018). Thus, the EITC may not be an effective approach to addressing these housing problems.

Turning to our housing affordability measures, we find support for Hypothesis 2: that the EITC will reduce mothers’ housing cost burdens. Following a $1,000 increase in the average EITC, single mothers are significantly less likely to pay more than 30 % of their pretax earnings toward housing costs (–3.9 percentage points) and are significantly less likely to pay more than 50 % of their pretax earnings toward housing costs (–5.2 percentage points). This estimate does not include the EITC transfer itself. In supplemental analyses, we added mother’s own EITC to her income and found further reductions in cost burdens (–5.4 and –7.6 percentage points for 30 % and 50 % of pretax earnings, respectively).

Does the EITC Affect Single Mothers’ Living Arrangements?

To examine whether the EITC changes the living arrangements of single mothers, we study its links with doubling up, multigenerational coresidence, household size, and crowding; these results are shown in Table 5. For doubling up, we find support in all three data sources for Hypothesis 3: the EITC reduces the likelihood of doubling up. A $1,000 increase in the average EITC significantly reduces doubling up by 1.3 and 2.1 percentage points in the ACS and CPS, respectively, compared with 10.6 percentage points in the FFCWS. The FFCWS estimate is larger likely because rates of doubling up are much higher in the FFCWS than in the ACS and CPS, probably driven by the birth cohort nature of this study: doubling up is especially common in early childhood (Pilkauskas et al. 2014).

Table 5.

Effect of the EITC on living arrangements and crowding

| CPS | ACS | FFCWS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living Arrangements | |||

| Doubled up | −0.021** | −0.013*** | −0.106*** |

| (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.014) | |

| Living in multigenerational household | −0.021*** | −0.004* | −0.046*** |

| (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| Doubling up in someone else’s homea | −0.065*** | ||

| (0.014) | |||

| Named on the lease or mortgagea | 0.094*** | ||

| (0.016) | |||

| Number of people in the household | −0.018 | −0.022† | 0.970*** |

| (0.017) | (0.012) | (0.047) | |

| Number of adults in the household | −0.308*** | ||

| (0.032) | |||

| Number of children in the household | 1.329*** | ||

| (0.033) | |||

| Household Crowding | |||

| Crowding | −0.021*** | ||

| (0.004) | |||

| Number of Observations | 85,089 | 757,977 | 9,928 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses. Coefficients represent the effect of a $1,000 increase in the simulated EITC benefit on outcomes. The CPS and ACS models include demographic and state contextual characteristics; state, year, and number of child fixed effects; and state-specific time trends. FFCWS models include demographic and state contextual characteristics, year, and individual fixed effects. Each cell represents a separate regression. The sample is restricted to single mothers with less than a college degree and with at least one coresident child under the age of 19. The CPS and ACS are also restricted to mothers aged 19–45. Single mothers residing in public housing are excluded from the CPS and FFCWS.

Sources: Current Population Survey (CPS) 1990–2016. Census 1990/American Community Survey 2000–2016. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) 1998–2016.

Information not asked in Year 1 of the FFCWS.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Turning to the effects on multigenerational coresidence, we find that all the reduction in doubling up in the CPS is driven by a significant reduction in the likelihood of living in a multigenerational household (–2 percentage points). In comparison, in the ACS and FFCWS, the reduction in multigenerational households only explains, respectively, about one-third or one-half of the reduction in doubling up (the estimate in the ACS is only marginally significant and not robust to Bonferroni adjustments). In the FFCWS, we can distinguish doubling up in someone else’s home from one’s own home. We find that the EITC significantly reduced doubling up in someone else’s home by 6.5 percentage points, accounting for about 60 % of the overall reduction. Consistent with this decline in the likelihood of doubling up in someone else’s home, we also find that single mothers in the FFCWS are significantly more likely to be named on the lease or mortgage as a function of EITC generosity. A $1,000 increase in average EITC benefits leads to a 9.4 percentage point increase in the likelihood of being named on the lease or mortgage, an indicator that single mothers are residing in their own homes.

We also examine living arrangements by studying the number of people in the household. Although not statistically significant, in both the CPS/ACS, we find that an increase in the EITC reduces the total number of people in the household by 0.02 people. The results in the FFCWS, however, are very different. We find a significant increase in the total number of people in the household following an increase in the EITC, despite a decline in doubling up. To examine this seemingly contradictory finding, we separately analyze how the EITC affects the number of adults and the number of children residing in the household in the FFCWS. When we estimate how the EITC affects the total number of adults in the household, we find that a $1,000 increase in the average EITC leads to a significant 0.31 person reduction in the number of adults residing in the household. In contrast, a $1,000 increase in the EITC leads to a significant 1.3 person increase in the number of children residing in the household. These findings suggest that the EITC reduces the total number of adults in the households; however, the evidence also points to potential effects on fertility, or suggests that single mothers may take in additional children—say, of friends or family—when they have more resources from the EITC. Future research is needed to determine whether the EITC increases fertility or whether this is a function of the cohort sample. Finally, as predicted in Hypothesis 3, given the reduction in doubling up and multigenerational coresidence, we also find that the EITC significantly reduces household crowding by 2 percentage points in the ACS.

Robustness Checks

We conduct a number of sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings in the ACS and the CPS. First, in Table A2 in the online appendix, we present results separately for (1) the full sample of single mothers, (2) mothers who are respondents, and (3) mothers who are nonrespondents for the outcomes that do not rely on the household roster for accurate coding. In both data sources, the vast majority of single mothers are, indeed, the respondents for the household rather than a nonrespondent. In the CPS, approximately 75 % of the single mothers in the sample are the respondent, and 85 % of single mothers in the ACS are the respondent. In running our analyses on the full sample of mothers rather than just respondents, we find nearly identical results to those reported for respondents only. For the nonrespondents, we find somewhat weaker effects on all outcomes.

Second, we run three placebo tests on groups that traditionally have lower rates of EITC eligibility: single childless women, college-educated mothers, and married parents; results are shown in Table A3 in the online appendix. As anticipated, we find little evidence to suggest the EITC affects the housing and living arrangements for any of these groups (although a coefficient is occasionally significant, none are robust to Bonferroni adjustments).

Third, to address the concern that state EITC variation may not be exogenous to housing outcomes, in Table A4 (online appendix), we run an analysis partitioning our treatment variable into its state and federal components.14 Results indicate that the findings for living arrangements are largely driven by the federal expansions to the EITC.

Fourth, because homeowners may be affected differently than renters, we run the analyses comparing homeowners with renters (and with subsidized renters in the CPS). As shown in Table A5 (online appendix), we find that renters (with or without subsidies), rather than homeowners, drive most of our results.15

Fifth, following earlier research, we run a difference-in-differences model analyzing two federal expansions to the EITC (that are incorporated in the reduced-form model): (1) the early 1990s expansion that expanded benefits for two-child households, and (2) the federal expansion for households with three or more children as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. The online appendix describes the method in more detail, and Table A6 shows the results. Although we find few statistically significant estimates in the CPS following the federal EITC expansions in the early 1990s, point estimates are similar to those in Tables 5 but are less precise. For the ARRA expansion, we find no significant effects in the CPS, but the point estimates are in the same direction as in the reduced-form analyses. In the ACS, however, we find evidence that after the ARRA expansion, households with three or more children were significantly less likely to be cost-burdened (–2 percentage points) and less likely to be doubled up (–1 percentage points).

Last, we conduct a similar set of analyses in the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Although the SIPP has a number of limitations (preference for a household head, few housing and living arrangement measures, and panels only four years long), we use the panel nature of the data to test the robustness of our findings using individual fixed effects (see Table A7, online appendix). We find a significant reduction in both doubling up (–6 percentage points) and living in a multigenerational household (–3 percentage points).

Discussion

Results of this study indicate that the EITC, the largest cash transfer program for low-income families in the United States, has a significant effect on the housing and living arrangements of single mothers. From previous research (and corroborated with our own analysis), we know that the EITC increases employment and earnings of single mothers (e.g., Hoynes and Patel 2018; Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001). We hypothesize that this increased income could in turn affect the housing and living arrangements of single mothers. First, we hypothesize that the EITC will reduce homelessness and eviction/foreclosures, but we find little evidence to support this hypothesis. There are a few reasons why this might be the case. Although average EITC transfers are relatively large, they may not be sufficient to offset extreme household shocks that lead to evictions. Evictions and foreclosures are increasingly common (Desmond 2016) but are still relatively rare, experienced by only 1 % to 2 % of mothers in our samples. Further, because both the CPS and the ACS are household surveys, we likely under-observe these outcomes. Thus, even if the EITC did reduce evictions, we might not find an effect with these data. Last, and perhaps most likely, in order to receive the EITC, a mother must have earnings. Prior research has found that those with incomes at the bottom of the income distribution (below 50 % of poverty) are least likely to be affected by the EITC (Hoynes and Patel 2018). If mothers who do not work are those who experience homelessness or eviction, then the EITC cannot effectively assist those households.

We find evidence to support Hypothesis 2, that the EITC would reduce mothers’ housing cost burdens. In keeping with other research (JCHS 2017), many mothers in our sample are cost-burdened, and one-half experience severe housing cost burdens (pay more than 50 % of earnings on housing). Both moderate and severe housing cost burdens are reduced when the EITC is expanded. This suggests that EITC expansions could help children because those in cost-burdened households are exposed to significantly higher levels of residential instability, parental depression, and food insecurity (Nobari et al. 2019). We are unable to further disentangle whether the EITC has differential effects by type of housing market, although this would be a fruitful area for future research.

Across all three data sets, we find support for Hypothesis 3: the EITC reduces doubling up, other shared living arrangements, household size, and crowding. Observed reductions in doubling up were coupled with suggestive evidence of a decline in the number of people in the household as well as reductions in household crowding. Prior work has linked crowding with poorer educational outcomes for children (e.g., Lopoo and London 2016) and increased vulnerability to adverse experiences (Edin and Shaefer 2015); thus, reductions in crowding may be especially important.

Although the findings that the EITC reduces cost burden and household crowding are clearly positive outcomes for families, whether our results for living arrangements represent positive outcomes is less clear. What our study makes evident is that single mothers have a preference to live independently. This finding is in keeping with studies of the elderly that similarly find a preference for independent living (e.g., Engelhardt et al. 2005). Likewise, this result is consistent with qualitative work that suggests mothers find living in someone else’s home incompatible with their ideals (Harvey 2017).

The increased likelihood of mothers being named on the lease or mortgage and reduced share of mothers doubling up in someone else’s home resulting from EITC expansions largely also represent positive outcomes for mothers and their children. Being named on the lease or mortgage suggests that mothers are experiencing increased economic stability. Similarly, moving out of someone else’s home likely translates to additional residential stability. Although doubling up in someone else’s household may be a stable arrangement, studies have suggested that those who live in someone else’s home are at higher risk of losing housing given that they are dependent on the goodwill of friends or family (Skobba and Goetz 2015; Wright et al. 1998).

Are reductions in multigenerational coresidence and doubling up more broadly positive or negative outcomes? Families choose to double up for a variety of reasons, which may yield positive or negative outcomes for families. For example, although doubling up is linked with rental savings (Pilkauskas et al. 2014), the extent to which resource sharing occurs can vary dramatically across households (Reyes 2018). Thus, it is unclear how moving out of a shared living arrangement will affect resources. Nor has research documented a clear-cut relationship between doubling up or multigenerational coresidence and family outcomes. Studies have found significant heterogeneity with respect to children’s well-being, finding no association (Augustine and Raley 2013), and some positive and some negative associations (e.g., DeLeire and Kalil 2002; Mollborn et al. 2011; Pilkauskas 2014). Similarly, studies of maternal employment have shown only short-term gains from multigenerational coresidence (Hao and Brinton 1997) but also negative associations with parenting (Chase-Lansdale et al. 1994). Thus, although it is not clear whether the reduction in shared living arrangements is a positive outcome, the findings do suggest the EITC increases independent living arrangements, those that are likely more stable.

This study is not without limitations. Our analysis assumes that single mothers claim all the children that reside in the household, but it is possible that other family members or nonresident fathers claim one or more children to maximize household tax refunds. This can be particularly complicated if more than one adult is eligible to claim the children residing in the household—say, through shared custody agreements among separated or divorced parents. If other family members claim any of the children residing in the household, this would result in measurement error, potentially biasing our estimates.

A related concern is that we use imputed EITC benefits in our analyses because reporting of EITC receipt is often quite poor in household surveys. Although EITC claiming tends to be high, at more than 80 % of those who are eligible, there are likely some single mothers in our sample who do not file their taxes or do not claim the EITC when they do file. We would thus attribute a nonzero EITC benefit to some households that do not, in fact, receive the EITC, again resulting in measurement error that might bias our estimates.

Another issue is whether the composition of single mothers itself is affected by the EITC, which may at least partially explain some of our findings. For instance, if single mothers who are more advantaged are less likely to marry as a function of EITC generosity, we may find a reduction in doubling up that is driven by this change in the composition of single mothers. The effect of the EITC on marriage is small (e.g., Herbst 2011; Michelmore 2018), and the magnitude of our results is likely too large to be completely explained by marriage effects. Another possibility is that the EITC induces more couples to cohabit (say, to move out of a household with family and friends into a household with an unmarried partner). In an additional analysis, we find no association between EITC expansions and cohabitation in the ACS (results available upon request). This suggests that our reduction in doubling up cannot be fully explained by a rise in cohabitation, although future work that can more fully examine the impact of the EITC on cohabitation is needed.

Despite some limitations, this study offers important insights for income, tax, and housing policy aimed at improving housing outcomes for low-income families. As states (and localities) contemplate implementing or expanding their EITCs, these results suggest the EITC improves housing through reduced cost burdens, increased likelihood of being named on the lease or mortgage, declines in household crowding, and reductions in the likelihood of doubling up in other people’s households. Scaling our results to the size of the average state EITC (about $250) implies a reduction in doubling up of 3 % to 8 %, living in someone else’s home by 10 %, cost burden by 2 % to 3 %, and household crowding by about 6 %. Thus, implementing or expanding EITCs may be an effective way to address some pressing housing issues. By improving housing outcomes and increasing the stability in living arrangements of children, the EITC may help reduce the intergenerational consequences of housing instability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan for funding for this project. This project was supported by Award Numbers R01HD036916 awarded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

One study modeled how the inclusion of the EITC in income reduces housing cost burdens (Stegman et al. 2004).

We include women who receive housing vouchers because they do not face the same restrictions as women in public housing. We find no evidence that the EITC affects the likelihood of living in public housing or having a housing voucher (results available upon request).

We also run analyses in the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP; see Table A7 in the online appendix) but do not include them here due to data limitations.

In a supplemental analysis, we restricted the CPS to the same years used in the ACS, and findings (available upon request) were similar to those presented here.

Additional details on the data and method, 15 sample states, sample restrictions, balance, and migration tests are available in the online appendix. The FFCWS has been used in previous research to examine the effect of EITC expansions on maltreatment (Berger et al. 2017).

Over the period studied, the CPS changed how it identified cohabiting partners. See the online appendix for details.

In the ACS and the CPS, we can identify only maternal grandparents. In the FFCWS, we can identify both maternal and paternal multigenerational households.

We conducted the same analyses using a sample of single mothers in the CPS, and results (available upon request) were virtually identical.

In the CPS, a $1,000 increase in the simulated benefit corresponds to a $794 increase in own EITC benefits among single mothers, which is consistent with previous research estimating about an 80 % take-up rate of the EITC (Currie 2004).

In the FFCWS, we include individual fixed effects rather than state or child fixed effects.

The state unemployment rate comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics: https://www.bls.gov/lau/. State GDP comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis Regional Data: https://www.bea.gov/regional/index.htm. Information on welfare benefits comes from the Urban Institute’s Welfare Rules Database: http://wrd.urban.org/wrd/Query/query.cfm.

In the CPS, we evaluate six outcomes of interest, requiring point estimates to be significant at p < .008 rather than at p < .05. Similarly, in the ACS, we evaluate eight outcomes, requiring significance at p < .006; and in the FFCWS, we evaluate nine outcomes, requiring significance at p < .006.

This finding is no longer significant at p < .05 after Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

We present analyses controlling for the both state and federal EITC, but models run separately (not controlling for the other) yielded similar results.

We find no significant relationship between EITC generosity and the likelihood of single mothers owning their own homes, so we do not believe that these results are driven by compositional changes in the single mothers who own or rent their homes.

References

- Augustine JM, & Raley RK (2013). Multigenerational households and the school readiness of children born to unmarried mothers. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 431–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian J, & Michelmore K (2018). The long-term impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on children’s education and employment outcomes. Journal of Labor Economics, 36, 1127–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Font SA, Slack KS, & Waldfogel J (2017). Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 15, 1345–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitler MP, Gelbach JB, & Hoynes HW (2006). Welfare reform and children’s living arrangements. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bratt RG (2002). Housing and family well-being. Housing Studies, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Seefedt KS, & Zelner S (2012). Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Social Science and Medicine, 75, 2215–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson D, Haveman R, Kaplan T, & Wolfe B (2012). Long-term effects of public low-income housing vouchers on neighborhood quality and household composition. Journal of Housing Economics, 21, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. (2016). Policy basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit. Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J, & Zamsky ES (1994). Young African-American multigenerational families in poverty: Quality of mothering and grandmothering. Child Development, 65, 373–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Hendren N, & Katz L (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity project. American Economic Review, 106, 855–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clampet-Lundquist S, & Massey DS (2008). Neighborhood effects on economic self-sufficiency: A reconsideration of the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 107–143. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J (2004). The take up of social benefits (NBER Working Paper No. 10488). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, & Gruber J (1996). Health insurance eligibility, utilization of medical care, and child health. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111, 431–466. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, & Yelowitz A (2000). Are public housing projects good for kids? Journal of Public Economics, 75, 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl M, DeLeire T, & Schwabish J (2009). Stepping stone or dead end? The effect of the EITC on earnings growth. National Tax Journal, 62, 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl GB, & Lochner L (2012). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. American Economic Review, 102, 1927–1956. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeire T, & Kalil A (2002). Good things come in threes: Single-parent multigenerational family structure and adolescent adjustment. Demography, 39, 393–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American city. New York, NY: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, & Gershenson C (2016). Housing and employment insecurity among the working poor. Social Problems, 63, 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, & Perkins KL (2016). Housing and household instability. Urban Affairs Review, 52, 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Dickert-Conlin S, & Houser S (2002). EITC and marriage. National Tax Journal, 55, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, & Lein L (1997). Making ends meet: How single mothers survive welfare and low-wage work. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Edin KJ, & Shaefer HL (2015). $2.00 a day: Living on almost nothing in America. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen IG (2017). What do we know about housing choice vouchers? (NYU Furman Center Working Paper). New York, NY: Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy; Retrieved from https://furmancenter.org/files/HousingChoiceVouchers_WorkingPaper_IngridGouldEllen_14AUG2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt GV, Gruber J, & Perry CD (2005). Social Security and elderly living arrangements: Evidence from the Social Security notch. Journal of HumanResources, 40, 354–372. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Lepore SJ, Shejwal BR, & Palsane MN (1998). Chronic residential crowding and children’s well-being: An ecological perspective. Child Development, 69, 1514–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WN, Sullivan JX, & Wallskog M (2016). The impact of homelessness prevention programs on homelessness. Science, 353, 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg DR, & Coutts E (1993). An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Shinn M, Wood M, Bell S, Dastrup S, Solari CD, …, & Abt Associates. (2016). Family Options Study: 3-year impacts of housing and services interventions for homeless families. Washington, DC: Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; Retrieved from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/Family-Options-Study.html [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Meekin S, Edin K, Tach L, & Sykes J (2015). It’s not like I’m poor: How working families make ends meet in a post-welfare world. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, & Brinton MC (1997). Productive activities and support systems of singlemothers. American Journal of Sociology, 102, 1305–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey H (2017, August). When mothers can’t “pay the cost to be the boss”: Roles and identity within doubled-up households. Winner of the SSSP Family Division Graduate Student Paper Award at the 67th annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Social Problems, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst CM (2011). The impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on marriage and divorce: Evidence from flow data. Population Research and Policy Review, 30, 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hoynes HW, & Patel AJ (2018). Effective policy for reducing poverty and inequality? The Earned Income Tax Credit and the distribution of income. Journal of Human Resources, 53, 859–890. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob BA (2004). Public housing, housing vouchers, and student achievement: Evidence from public housing demolitions in Chicago. American Economic Review, 94, 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob BA, & Ludwig J (2012). The effects of housing assistance on labor supply: Evidence from a voucher lottery. American Economic Review, 102, 272–304. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS). (2017). The state of the nation’s housing 2017 (Report). Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Jones LE, & Michelmore K (2018). The impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on household finances. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37, 521–545. [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Kling JR, & Liebman JB (2001). Moving to Opportunity in Boston: Early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 2, 607–654. [Google Scholar]

- Kling JR, Liebman JB, & Katz LF (2007). Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica, 75, 83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Labella MH, Narayan AJ, McCormick CM, Desjardins CD, & Masten AS (2019). Risk and adversity, parenting quality, and children’s social-emotional adjustment in families experiencing homelessness. Child Development, 90, 227–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold J, Getsinger L, Blumenthal P, Abazajian K, & Jordan R (2015). The housing affordability gap for extremely low-income renters in 2013 (Report). Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, & Newman S (2010). Housing and child development. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Lopoo LM, & London AS (2016). Household crowding during childhood and long-term education outcomes. Demography, 53, 699–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, & Sanbonmatsu L (2013). Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity. American Economic Review, 103, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, & Rosenbaum DT (2001). Welfare, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1063–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Michelmore K (2018). The Earned Income Tax Credit and union formation: The impact of expected spouse earnings. Review of Economics of the Household, 16, 377–406. [Google Scholar]

- Mills G, Gubits D, Orr L, Long D, Feins J, …, the QED Group. (2006). Effects of housing vouchers on welfare families (Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Google Scholar]

- Mollborn S, Fomby P, & Dennis JA (2011). Who matters for children’s early development? Race/ethnicity and extended household structures in the United States. Child Indicators Research, 4, 389–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykyta L, & Macartney S (2012). Sharing a household: Household composition and economic well-being: 2007–2010 (Current Population Report No. P60–242). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Economics and Statistics Administration. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Homeless Education. (2011). Education for homeless children and youth program: Data collection summary. Washington, DC: National Center for Homeless Education. [Google Scholar]

- Nobari TZ, Whaley SE, Blumenberg E, Prelip ML, & Wang MC (2019). Severe housing-cost burden and obesity among preschool-aged low-income children in Los Angeles County. Preventive Medicine Reports, 13, 139–145. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV (2012). Three-generation family households: Differences by family structure at birth. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 931–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV (2014). Living with a grandparent and parent in early childhood: Associations with school readiness and differences by demographic characteristics. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV, & Cross C (2018). Beyond the nuclear family: Trends in children living in shared households. Demography, 55, 2283–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2014). The prevalence and economic value of doubling up. Demography, 51, 1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes AM (2018). The economic organization of extended family households by race or ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 119–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, Flood S, Goeken R, Grover J, Meyer E, Pacas J, & Sobek M (2018). IPUMS USA: Version 8.0 [Data set]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS; 10.18128/D010.V8.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skobba K, & Goetz EG (2015). Doubling up and the erosion of social capital among very low income households. International Journal of Housing Policy, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, McPherson M, & Smith-Lovin L (2014). Social distance in the United States: Sex, race, religion, age, and education homophily among confidants, 1985 to 2004. American Sociological Review, 79, 432–456. [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB (1975). All our kin: Strategies for survival in a black community. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stegman MA, Davis WR, & Quercia R (2004). The Earned Income Tax Credit as an instrument of housing policy. Housing Policy Debate, 15, 203–260. [Google Scholar]

- Tax Policy Center. (2006). EITC distribution by filing status, 2000, 2003. Retrieved from http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/eitc-distribution-filing-status-2000-2003 [Google Scholar]

- Wright BR, Caspi A, Moffit TE, & Silva P (1998). Factors associated with doubled-up housing—A common precursor to homelessness. Social Service Review, 72, 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest KM, & McKenna CC (2014). Early childhood housing instability and school readiness. Child Development, 85, 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.