Abstract

Background

Efficacy of light therapy for non‐seasonal depression has been studied without any consensus on its efficacy.

Objectives

To evaluate clinical effects of light therapy in comparison to the inactive placebo treatment for non‐seasonal depression.

Search methods

We searched the Depression Anxiety & Neurosis Controlled Trials register (CCDANCTR January 2003), comprising the results of searches of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (1966 ‐), EMBASE (1980 ‐), CINAHL (1982 ‐), LILACS (1982 ‐), National Research Register, PsycINFO/PsycLIT (1974 ‐), PSYNDEX (1977 ‐), and SIGLE (1982 ‐ ) using the group search strategy and the following terms: #30 = phototherapy or ("light therapy" or light‐therapy). We also sought trials from conference proceedings and references of included papers, and contacted the first author of each study as well as leading researchers in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing bright light with inactive placebo treatments for non‐seasonal depression.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted and quality assessment was made independently by two reviewers. The authors were contacted to obtain additional information.

Main results

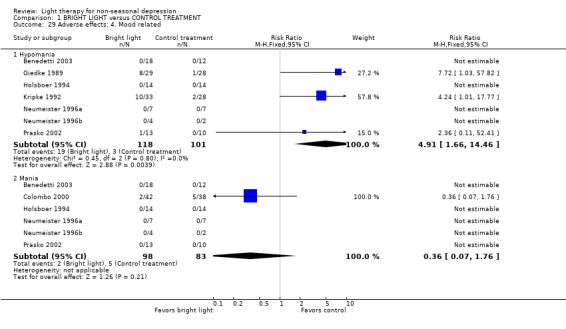

Twenty studies (49 reports) were included in the review. Most of the studies applied bright light as adjunctive treatment to drug therapy, sleep deprivation, or both. In general, the quality of reporting was poor, and many reviews did not report adverse effects systematically. The treatment response in the bright light group was better than in the control treatment group, but did not reach statistical significance. The result was mainly based on studies of less than 8 days of treatment. The response to bright light was significantly better than to control treatment in high‐quality studies (standardized mean difference (SMD) ‐0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.50 to ‐0.31), in studies applying morning light treatment (SMD ‐0.38, CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.14), and in sleep deprivation responders (SMD ‐1.02, CI ‐1.60 to ‐0.45). Hypomania was more common in the bright light group compared to the control treatment group (risk ratio 4.91, CI 1.66 to 14.46, number needed to harm 8, CI 5 to 20).

Authors' conclusions

For patients suffering from non‐seasonal depression, light therapy offers modest though promising antidepressive efficacy, especially when administered during the first week of treatment, in the morning, and as an adjunctive treatment to sleep deprivation responders. Hypomania as a potential adverse effect needs to be considered. Due to limited data and heterogeneity of studies these results need to be interpreted with caution.

Plain language summary

Light treatment for non‐seasonal depression

The reviewers conclude that the benefit of light treatment is modest though promising for non‐seasonal depression. The short‐term treatment as well as light administered in the morning and with concomitant sleep deprivation in sleep deprivation responders appear to be most beneficial for treatment response. Hypomania as a potential adverse effect needs to be considered. Due to limited data and heterogeneity of studies these results need to be interpreted with caution.

Background

Depressive disorders are disabling, recurring illnesses that affect every society. It has been estimated that 20‐48% of the population will be affected by a mood disorder at least once in a lifetime (Cassem 1995; Kessler 1996). Major depression is estimated to be the fourth most important cause of loss in disability‐adjusted life years (Murray 1996), but in the future it may be the first cause in developed countries.

Etiologic theories have linked both disordered physiology and psychology to disordered mood (Dubovsky 1999). One of the biological factors, disruption in biological rhythms (circa dies; about a day), has been suggested to play a causal role in mental illness, particularly in affective disorders (Kripke 1981; Goodwin 1982).

Both biological treatments and psychological treatments can usually be applied in the treatment of depression. Antidepressant medication has become the predominant form of biological treatment. The response rate has been considered to be only slightly better than the response for placebo treatment (Mulrow 1999; Khan 2000). In the beginning of the treatment, the response usually takes two to eight weeks or even more. Moreover, adverse effects of antidepressant drugs can limit acceptability. Effects of psychotherapy appear largely similar in magnitude to those of antidepressants (Elkin 1989).

Administration of bright light for treatment of a mood disorder with recurrent annual depressive episodes, seasonal affective disorder (SAD), has been shown to be effective. Light therapy has become a treatment of choice for SAD (Lam 1999), though a formal Cochrane review is not yet available. Efficacy of light therapy for non‐seasonal depression has been studied less, but a substantial number of small controlled trials are now available. The mechanism of action of light is not yet completely understood. Light is a potent phase‐shifting agent of circadian rhythms and acts on melatonin secretion and metabolism. Artificial bright light has also been reported useful for treating sleep disorders (Campbell 1998; Chesson 1999), seasonal lethargy (Partonen 2000), premenstrual depression (Parry 1998), bulimia (Lam 1998), adaptation to timezone (Cole 1989) and work‐shift changes (Eastman 1999).

The minimal intensity of artificial light that appears necessary for an antidepressant effect in SAD is 2500 lux for two hours, or alternatively, a brighter light exposure of 10,000 lux for 30 minutes (Tam 1995). Bright light appears to be safe and side effects are mild, if the light does not contain substantial energy in the ultraviolet spectrum (Rosenthal 1989). For patients with bipolar disorder, light therapy is most safely administered with mood stabilizers because of the risk of mania (Kripke 1998). In SAD light has been shown to be most effective when administered in the morning (Terman 2001). Both morning and evening light have been used for non‐seasonal depression, but there is no consensus of the optimal timing of the treatment. In addition to efficacy and timing of light therapy for non‐seasonal depression, several issues such as the length of light treatment and preventive aspects are not yet fully understood. There have been interesting reports on combined treatment of light with antidepressant medication (Beauchemin 1997) and with sleep deprivation (Neumeister 1996).

Objectives

The main objective was to evaluate clinical effects of light therapy in comparison to the inactive placebo treatment for non‐seasonal depression.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Inclusion criteria All relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Exclusion criteria 1. Quasi‐randomized studies. Quasi‐randomized studies were determined as studies in which a method of allocating participants to different forms of care that is not truly random; for example, allocation by date of birth, day of the week, medical record number, month of the year, or the order in which participants are included in the study; and 2. Controlled clinical studies (CCTs).

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria People with a diagnosis of non‐seasonal depression, irrespective of gender or age. In addition to major depressive disorder, we included dysthymia, minor depression, bipolar disorder, and other depressive conditions that were the primary focus of treatment in the study. Depression was being diagnosed according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) criteria, or other validated diagnostic instruments, or was being assessed for levels of depressive symptoms through self‐rated or clinician‐rated validated instruments.

Exclusion criteria 1. Seasonal depression, such as Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) and Sub‐Syndromal Seasonal Affective Disorder (Sub‐SAD). As some studies might include both seasonal and non‐seasonal depressive patients, these studies were not included if more than 20% of the cases in a sample suffered from seasonal symptomatology (SAD or Sub‐SAD). If the number of cases with seasonal depression was not more than 20% in a study sample, these patients were included with non‐seasonal patients in the analysis. Even though we did not expect results to be influenced by seasonality of minor extent, sensitivity analysis were undertaken to evaluate the effect of these studies; and 2. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD).

Types of interventions

1. All forms of bright light therapy, in terms of timing, intensity, and duration of light exposure and the device being used. Bright light could be administered either alone, or concomitant with antidepressant drug therapy, with sleep deprivation, or with both adjunctive treatments, so long as light and placebo were administered randomly and the concomitant therapies were not adjusted or biased according to light/placebo assignment; and 2. Inactive placebo treatment (dim light or other inactive treatment).

Types of outcome measures

Principal outcomes of interest were: 1. Depression symptom level. This is usually measured using a variety of rating scales, for example, clinician‐rated scales such as the Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression (HRSD) (Hamilton 1960), and self‐rating scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961). Symptom levels may be presented as continuous (mean and Standard Deviation [SD]) or dichotomous outcomes (remission/recovery vs. non‐remission/non‐recovery); 2. Adverse effects, particularly mania, the elevation of mood, eye irritation, and headache. These are usually presented as dichotomous outcomes (adverse effect yes/no); 3. Acceptability of treatment as assessed indirectly by the number of persons dropping out of the studies; and 4. Deterioration in mental state or relapse during treatment.

Information were also sought regarding other outcomes including (objective or subjective measures): 1. Overall clinical improvement; 2. Quality of life; 3. Cost effectiveness; and 4. Long‐term follow‐up.

All outcomes were grouped by time, i.e., duration of treatment ‐ short term (up to one week), medium term (eight days to eight weeks) and long term (more than eight weeks). An overall analysis was also performed. In crossover studies, only the first treatment phase prior to crossover (first arm) was included.

Search methods for identification of studies

1. Electronic databases: See: Collaborative Review Group search strategy The Depression Anxiety & Neurosis Controlled Trials register (CCDANCTR December 2002)), comprising the results of searches of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL (1982 ‐), EMBASE (1980 ‐), LILACS (1982 ‐), MEDLINE (1966 ‐), National Research Register, PsycINFO/PsycLIT (1974 ‐), PSYNDEX (1977 ‐), and SIGLE (1982 ‐ ) was searched using the following terms:

Intervention = phototherapy or ("light therapy" or light‐therapy);

2. Reference lists: we searched all references of articles selected for further relevant trials;

3. Conference proceedings: we sought studies from conference proceedings if available;

4. Authors: we contacted the first author of each study as well as leading researchers in the field regarding additional information and unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection Two reviewers (AT and either DK or TE) independently inspected all study citations of published and unpublished trials identified by the searches to assess their relevance to this review. Full reports of the studies of agreed relevance were obtained. When disagreement occurred, the full article was acquired for further inspection. If there was disagreement with the inspection of the report, this was resolved by discussion and further information was sought from the authors when needed.

If the report did not comment on randomization or double blindness in allocation, and additional information could not be obtained from the authors, the study was categorized as 'not randomized' and excluded from the analysis.

Quality assessment Two independent reviewers (AT and either DK or TE) assessed the methodological quality of the selected trials using the criteria based on the guidelines included in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Mulrow 1997). Should disagreements have arisen, resolution was attempted by discussion. If this was not possible and further information was needed to clarify into which category to allocate the trial, data were not entered and the trial was allocated to the list of those awaiting assessment. A rating was given for each trial based on the three quality categories. These criteria are based on the evidence of a strong relationship between the potential for bias in the results and the allocation concealment and are defined as below:

A. Low risk of bias (adequate allocation concealment); B. Moderate risk of bias (intermediate, some doubt about the results); and C. High risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment).

Only trials in Category A or B were included in the review. Randomized studies as well as double‐blind studies with no further information on randomization process were included in Category B.

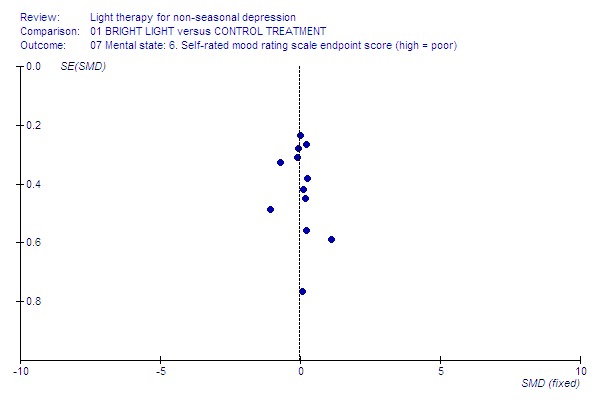

Addressing publication bias Data from all identified and selected trials were entered into a funnel graph (trial effect versus trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias. If appropriate, funnel plot asymmetries (suggesting potential publication bias) were investigated by visual inspection and formal statistical tests (Egger 1997).

Data extraction Two reviewers (AT and either DK or TE) independently extracted data from selected trials using data extraction forms. If disputes arose, resolution was attempted by discussion. If further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, data were not entered until the authors were contacted and additional information was obtained.

Data synthesis The data was synthesized using Review Manager 4.2.1. software. Outcomes were assessed using continuous (for example, outcome figures of a depression scale) or dichotomous measures (for example, 'no important changes' or 'important changes' in a person's behavior, adverse effects information).

1. Continuous data Where trials reported continuous data, as a minimum standard, the instrument that has been used to measure outcomes had to have established validity, for instance, to have been published in a peer‐reviewed journal. The following minimum standards for instruments were set: the instrument shall either be a) self‐report, or b) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist); and the instrument should be a global assessment of an area of functioning. Continuous data were reported as presented in the original studies, without making any assumptions about those lost to follow‐up. Whenever possible, the opportunity was taken to make direct comparisons between trials that used the same measurement instrument to quantify specific outcomes. For continuous data, reviewers calculated weighted mean differences (WMDs). Where continuous data were presented from different scales rating the same outcomes, the reviewers applied standardized mean differences (SMDs).

2. Dichotomous data Where dichotomous outcomes were presented, the cut‐off points designated by the authors as representing 'clinical improvement' were identified and used to calculate relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). These cut‐off points are, however, often defined quite differently, and only those studies that had used similar cut‐off points (e.g., 20% reduction in scores or 50% reduction in scores) were combined into a single pooled estimate. For undesirable outcomes an RR that is less than one indicates that the intervention was effective in reducing the risk of that outcome. As a measure of effectiveness, the number needed to treat (NNT) or the number needed to harm (NNH) statistic was calculated together with its confidence interval. Where patients were lost to follow‐up at the end of the study, it was assumed that they had had a poor outcome and once they were randomized they were included in the analysis (last observation carried forward analysis). If patients had dropped out after randomization due to non‐compliance, lack of efficacy, relapse, or for unknown reason, it was assumed that those cases also had failed to improve. However, it needs to be acknowledged that categorizing these drop‐out subjects as "failures" might overestimate the number of subjects with poor outcome.

Fixed effect model and random effects model For both dichotomous and continuous data, a fixed effect model was used to analyze data, but if significant heterogeneity (p<0.05) was found, a supplementary random effects model was computed. A random effects model will tend to give a more conservative estimate, but the results from the two models should agree when the between‐study variation is estimated to be zero.

Parametric tests and non‐parametric data Data on outcomes are not normally distributed. To avoid applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data the following standards were selected for all data derived from continuous measures before inclusion: 1. Standard deviations (SDs) and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable form the authors; and 2. SD, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean, as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the center of distribution (Altman 1996).

Data that did not meet the standards were not planned to be entered into a meta‐analysis (which assumes a normal distribution) but reported in the "Other data" tables.

Although in our protocol we stated that we would only use data that met our criteria 1. and 2., during the analysis, given the scarcity of results, we decided to include also data which did not meet the criterion 2. We performed an additional sensitivity analysis to study the effect of this procedure and have indicated this in the Results section.

Post‐intervention scores (data at endpoint) were used in the meta‐analysis. Because change scores take into account pre‐existing differences between groups at baseline, mean change scores and SDs were extracted where available and pooled where appropriate.

Graphs In all cases the data were entered into the Review Manager in such a way that in graphs the area to the left of the 'line of no effect' indicates a favorable outcome for the relevant intervention.

Subgroup analyses and heterogeneity Investigation of sources of heterogeneity was performed with the sub‐group analysis. We investigated whether: 1. Trials studying long term treatment effects differed in their results from trials evaluating short term treatment; 2. Trials using inpatients differed in their results from trials using outpatients; 3. Trials using concomitant sleep deprivation differed in their results from trials not using sleep‐deprivation; 4. Trials using concomitant drug treatment differed in their results from trials not using drug treatment; 5. Trials with bright light treatment in the morning differed in their results with trials administering light in the evening, at night, or at various times of a day; 6. Trials using a light box differed in their results from trials using some other lighting device; 7. Trials with higher intensity of light treatment (> 2500 lux) differed in their results from trials with lower intensity of light; 8. Trials with longer duration of light treatment differed in their results with trials with shorter duration of light; and 9. Trials using very old or very young subjects differed in their results from trials using adult subjects.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to exclude the studies including following conditions: 1. Studies of lower methodological quality; 2. Mixed study sample of non‐seasonal and seasonal patients; and 3. Robustness of the findings based on dichotomous outcomes in which it was assumed that drop‐outs are treatment failures.

As heterogeneity was found in many statistical analyses, a random effects model was also applied as an additional sensitivity analysis for the results from the fixed effect model. Both of the results are described in the Results section.

Excluded studies All excluded studies were listed with the reason for exclusion.

Results

Description of studies

1. Excluded studies Twenty‐five studies were excluded, either because they were not randomized trials (15 studies), more than 20% of the participants were suffering from seasonal depression or seasonal difficulties (3 studies), participants were not clinically diagnosed to have depression (1 study), interventions were not standardized (2 studies), active treatment was combined with two other treatments not balanced in the placebo group (1 study), control treatment was also clearly active (in one study the control treatment being 2500 lux bright light and in another study exercise), or the comparison was between depressive patients with atypical symptoms and patients with classical symptoms (1 study). The table Characteristics of excluded studies describes the details of exclusion as follows: if the study was eligible by its allocation method (randomized), then information on participants has been listed. If the participants have fit our criteria, then the reason for exclusion has been the intervention of the study.

2. Included studies We identified 20 studies for inclusion in this review, dating from between 1983 and 2002. In two studies, randomization was performed after sleep deprivation for responders and nonresponders separately. Both of these studies were separated to two individual studies according to the randomization procedure (Neumeister 1996a; Neumeister 1996b; Fritzsche 2001a; Fritzsche 2001b). One study (Bloching 2000) has been reported as conference abstracts only with additional data supplied by the author. Two of the studies (Schuchardt 1992; Sumaya 2001) have provided insufficient information at the moment, and the authors have been contacted for additional data.

Length of trials Thirteen studies presented data on 'short term' treatment (up to one week). Two studies lasted only for one day, either one single hour (Kripke 1983) or one night (Giedke 1989). Seven studies fell into the 'medium term' (eight days to eight weeks) category, the longest ones being of 4 weeks in duration (Schuchardt 1992; Holsboer 1994). In one of these medium term studies (Holsboer 1994) administration of bright light was decreased to three times per week during the last three weeks of treatment. None of the trials fulfilled our criterion for the 'long term' category (more than eight weeks).

Participants Seventeen studies reported on participants mostly suffering from major depressive disorder. Ten studies had both unipolar and bipolar patients in their sample. Inclusion and exclusion criteria varied among studies (see Characteristics of Included Studies table). Participants were more likely to be female than male (60% versus 40%, respectively), and had a mean age of 50 years. Assessment of seasonality either in exclusion criteria or in use of seasonality scales was commented on in 13 out of 20 studies. As almost all patients had major depressive disorders, by definition this excludes the existence of SAD and subsyndromal SAD.

Setting Almost all studies took place in the hospital or long‐term care facility. Only two studies (Loving 2002; Schuchardt 1992) assessed outpatients. None of the studies were multicenter. Only five studies (Mackert 1990; Yamada 1995; Fritzsche 2001a; Fritzsche 2001b; Benedetti 2003) reported on the time of the year when the study was performed.

Study size Study size ranged from 115 people (108 completers) (Colombo 2000) to 6 people (Neumeister 1996b), with a mean size of 31. The total number of patients from the 20 studies that provided data for this review was 620.

Interventions Bright light therapy was administered in a wide range of intensities (from 400 lux to 10,000 lux), several colors such as white (active), green (active), red (control) and yellow (control) wave lengths, and at different times in a day. The duration of active treatment varied between 30 minutes (Benedetti 2003; Loving 2002) and the whole night, i.e., eight (van den Burg 1990) or nine hours (Giedke 1989). Duration/brightness in relation to efficacy was not assessed in any of the studies. Eleven studies administered bright light in the morning: one of these studies (Yamada 1995) had used morning light to one group and evening light to another group of their patients. There was only one study (Holsboer 1994) that had used evening light only. Two studies (Neumeister 1996a; Neumeister 1996b) used both morning and evening treatments, and two studies (Giedke 1989; van den Burg 1990) used the whole night light treatment. Inactive placebo treatment was almost always dim light, mostly red (10 studies) and varied in intensity between 25 to 500 lux. One study described the use of a negative ion generator as inactive treatment (Benedetti 2003). The device for light therapy was usually a light box, but also other lighting approaches were used. Three studies (Giedke 1989; van den Burg 1990; Holsboer 1994) described dim illumination in a room as inactive treatment.

Light was administered adjunctive to sleep deprivation in nine studies, and in two additional studies (Kripke 1983; Kripke 1987) the participants were awakened before their usual wake up time for light treatment. One study (Benedetti 2003) reported that active treatment group patients were awakened 1 1/2 hours earlier than patients in the control group, which makes the groups slightly unequal to compare and can be considered as a minor additional sleep deprivation for patients in the active treatment group. As early awakening was not intended as an additional treatment as such and was not designed to be an active treatment, this study was not excluded from the concomitant analysis. Standardized adjunctive pharmacotherapy was applied in seven studies, and in ten studies, concomitant drug treatment of the participants was kept unchanged. One study (Colombo 2000) had applied both sleep deprivation and standardized drug treatment (lithium) in the study design. In another study (Holsboer 1994), the sleep deprivation intervention could not be included in the evaluation, as the intervention groups were not comparable. Only two studies (Mackert 1990; Yamada 1995) had applied bright light only, without sleep deprivation or pharmacotherapy.

Outcomes In addition to general mental state outcome assessment, we analyzed clinician‐rated and self‐rated mental state separately. In part of the studies self‐rating instruments were the only method to evaluate the outcome status of the participants (van den Burg 1990; Moffit 1993; Colombo 2000; Sumaya 2001; Loving 2002), and these scores were used to assess the general mental state. Deterioration in mental health or relapse during the treatment was assessed by dichotomous scales. Acceptability of treatment was measured indirectly by patients dropping out of the study. Adverse effects in detail were evaluated by dichotomous scales and by continuous symptom scales. Abbreviations of the tests are explained in the footnotes of the Characteristics of Studies tables.

Almost all studies reported stringent criteria for the diagnosis of depression: only one study did not report on diagnostic criteria (Kripke 1983), and one study assessed the level of depressive symptoms through a self‐rated validated instrument, the Geriatric Depression Scale (Sumaya 2001).

Improvement of condition was dichotomously defined in three studies as percentage or number of respondents with 50% reduction in HDRS (Holsboer 1994; Benedetti 2003; Loving 2002). As one study (Prasko 2002) applied an additional criterion of HDRS scores less than 8 to improvement of condition, this study was not included in the meta‐analysis of outcome of improvement, but reported in the Other data table. Studies of another group (Fritzsche 2001a; Fritzsche 2001b) had also applied the same additional criterion to the 50% reduction definition, but as they only had used the cutpoint to determine sleep deprivation responders and nonresponders before randomization, this dichotomization could not be included in the analysis.

Outcome scales Details of scales that provided usable data are described below.

As some of the studies had applied several rating scales to assess the depressive mental state, the reviewers made their choice for inclusion of data in the meta‐analysis as follows: firstly, priority was given to the most commonly used rating scales HDRS and BDI. Secondly, if the authors had used the rating scale to determine the treatment response or expressed their preference over scales by the order of presenting the results, the following choices were made: AMS (Bloching 2000), M‐S (Giedke 1989), D‐S (Mackert 1990) and D‐S (Holsboer 1994). If follow‐up scores were available even if a different outcome scale had been used, the scores were utilized in the analysis: AMS (van den Burg 1990).

Mental state scales Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton 1960) is an observer scale and is designed to be used on patients already diagnosed as suffering from affective disorder. The scale contains 17 or 21 variables measured on either a five‐point or a three‐point scale. Among the variables are: depressed mood, suicide, work and interests, retardation, agitation, gastrointestinal symptoms, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, loss of insight, and loss of weight. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979) is a semi‐structured symptom scale that is measuring the severity of depression. The twelve items cover the eight clinical features listed in the DSM‐III‐R definition of major depressive disorder. Scoring of either 0 to 3 (with operational criteria) or 0 to 6 (with undefined intermediate steps) can be used. Higher scores indicate more severe depression.

Adjective Mood Scale (AMS), a.k.a. Befindlichkeits‐Skala (Bf‐S) (von Zerssen 1983) is a self‐rated mood scale that is measuring subjective impairment. There are 28 items which are scored from 0 (not depressed) to 56 (severely depressed), and it is particularly suited for frequent use at short intervals.

Depression Scale (D‐S) (von Zerssen 1986) is another self‐rated instrument that is measuring depression.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961) is a self‐rated symptom scale that assesses the severity of depressive states. There are 21 items which are scored 0 to 3, based on the degree of the symptoms. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Yesavage 1983) is a self‐rated instrument that assesses depression in geriatric population. The 30‐item instrument consists of yes/no format assessments of cognitive complaints, self‐image, energy and motivation, future/past orientation, agitation, and social behavior. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

Global assessment scales Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) (Guy 1976) is a rating instrument that assesses severity of illness. It consists of three global scales (items), of which two items, 'Severity of illness' and 'Global improvement', are rated on a seven‐point scale; while the third, 'Efficacy index', requires a rating of the interaction of a therapeutic effectiveness and adverse reactions. Lower scores indicate decreased severity and/or greater recovery.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (Aitken 1969) is a rating instrument for global assessment of a particular item or the severity of illness. The instrument has a millimeter scale from 0 to 100, where 0 stands for an optimally healthy condition and 100 for a very severe condition of illness. In assessment of mood, 100 denotes extremely happy feelings. This rating scale was used to measure subjective mood levels in four studies (Mackert 1990; Holsboer 1994; Bloching 2000; Colombo 2000).

Adverse effect scales Complaint List (C‐S) (von Zerssen 1986) is a self‐rated instrument that assesses various symptoms. Specific items such as fatigue, nausea, irritability, inner restlessness, restless feeling in the legs, excessive need of sleep, insomnia, trembling, and neck and shoulder pain were used to represent side‐effects that have been described in the literature. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

Fisher's Somatic Symptom/Undesired Effect Checklist (FSUCL) (CIPS 1986) is a semi‐structured clinician‐rated symptom scale that evaluates adverse effects. It consists of six different facets of adverse effect items (central nervous system related, 5 items; gastrointestinal complaints, 6 items; vegetative, 5 items; neurological, 7 items; headache, 1 item; cardiovascular, 2 items) with a total of 26 items. Each item is scored on a 4‐point scale, with 0 indicating absence and 3 indicating serious severity. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

3. Studies awaiting assessment One study (Deltito 1991) has evaluated the intensity of light therapy in patients with non‐seasonal depression, but the outcome measures have reported light therapy contrasted between bipolar and unipolar patients. To assess the difference between bright and dim light intervention, the authors have been contacted for further details, but no reply has been received as yet.

4. Ongoing studies One study (Goel 2001) reports an ongoing study on bright light and negative ion treatment in patients with chronic depression, and the other (Zirpoli 2002) is evaluating the sensitivity of melatonin to light suppression and light treatment in depressed and non‐depressed children.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomization All included studies described themselves as randomized, but presented little methodological detail to elaborate on the truly random nature of allocation. Three studies (Moffit 1993; Kripke 1987; Benedetti 2003) had used the method of block randomization. One study (Schuchardt 1992) had used a randomized list, but only two studies (Moffit 1993; Benedetti 2003) described a truly random method of allocation (computer generated randomization with no stratification; sealed envelopes). Apart from these studies, no other studies described a method that would prevent foreknowledge of allocation.

Blinding of assessment Blinding of assessment in administration of light therapy is more difficult than in studies with drug intervention, since the active treatment due to its brightness looks dissimilar to the control treatment. Subjects cannot fail to perceive the treatment and cannot be literally blind to treatment, though they may not know which is intended as the active treatment. Eleven studies described double blind assessment, i.e., a patient and an experimenter blind to the details of light treatment. It needs to be understood that these studies attempted to conceal from patients which was the active treatment, but patients were certainly not blind to the brightness of the light, and therefore, no patient was 'blind'. Four studies were single blind, and in two of them (Colombo 2000; Benedetti 2003) explained that raters could not keep themselves blind due to patients' questions. In five studies blinding was not stated. Patients' expectations were studied in two studies only (Mackert 1990; Kripke 1992), and this issue was commented on but not studied in two more studies (Colombo 2000; Benedetti 2003).

Data reporting As studies frequently presented data on graphs and by p‐values, raw data were not always available for synthesis. Standard deviations (SDs) were not routinely reported in all studies. If the participants of the studies had been dropping out from the study after randomization, data reporting was not always sufficient in terms of the reasons for dropping out or the group that the participants had belonged to. The method of 'last observation carried forward' was not declared in the studies except for in one personal communication (Kripke 1992). It remained unclear if the studies had applied a true 'intention to treat' analysis, as numbers of patients at endpoint results (when reported) rarely matched those reported at baseline. In four out of five studies with a crossover design (Kripke 1983; Kripke 1987; Giedke 1989; van den Burg 1990), the data of the first arm were available and made meta‐analysis approach possible. The authors of the fifth crossover study (Sumaya 2001) have been contacted for additional information.

Apart from two category A studies (Moffit 1993; Benedetti 2003), all other studies were located in the quality category B (randomized but concealment of allocation unclear). In almost one third of the studies, the numbers of patients allocated to each treatment group were identical. When allocating by chance this is improbable unless block randomization has been used. The studies did not comment on this.

Effects of interventions

The search The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group's register found 160 records (January 2003). After two reviewers independently screening the searches, altogether 33 possible citations were identified. The evaluation of the full reports of the search, screening the report references, conference proceedings available, and correspondence with authors of identified studies yielded 49 reports of 20 separate trials judged to fulfill the inclusion criteria of the review. Most of the excluded studies were non‐randomized, open studies. According to the study protocol, the studies evaluating light therapy for seasonal depression were beyond this review and will be included in another Cochrane review.

General comments If there were several active intervention groups in the study, we grouped together all the experimental groups (active treatment group) and compared them collectively with the control group. To evaluate the effect of inclusion of studies with possible non‐normal distribution in the analysis, we evaluated primary mood rating scale endpoint scores with studies with normal distribution only, i.e. following the original criteria of our protocol 'SD multiplied by two being less than a mean'. However, as the result (details given below) was similar to that of a whole group, all outcomes have been analyzed without exclusion of studies in which normality cannot be assumed. In dichotomous variables we categorized drop‐out subjects as "failures". It needs to be kept in mind that this categorization we made might have overestimated the number of subjects with poor outcome.

To evaluate the effect of inclusion of studies that did not meet strict criteria of normal distribution, we excluded the studies in which the mean was less than SD multiplied by two (Kripke 1983; Giedke 1989; Holsboer 1994; Yamada 1995; Fritzsche 2001a; Benedetti 2003; Loving 2002; Prasko 2002). Using the primary mood rating scale endpoint score, the outcome result of the studies that were normally distributed did not differ from that of the whole group.

Overall quality In general, the quality of reporting was poor. All but two trials reported the randomization procedure without adequate information on allocation concealment. Blinding procedures were also generally inadequately described. Many studies did not report the number of drop‐outs and did not specify reasons for drop‐out. The trials did not report if intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. The meta‐analysis results are based on 18 studies, because the mean outcome scores and SDs of two studies (Schuchardt 1992; Sumaya 2001) were not available at the time of preparation of the review. Both of these studies had reported significant benefits of bright light.

Specific comments

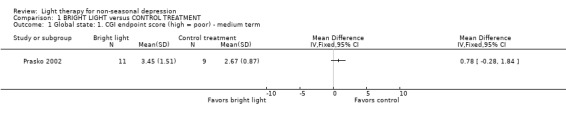

Global state The information of patients with no clinical improvement/deterioration by dichotomous CGI criteria could be extracted in none of the studies. Continuous CGI endpoint scores showed that, based on a small medium term study (Prasko 2002), there was a trend for the control treatment being more effective than bright light.

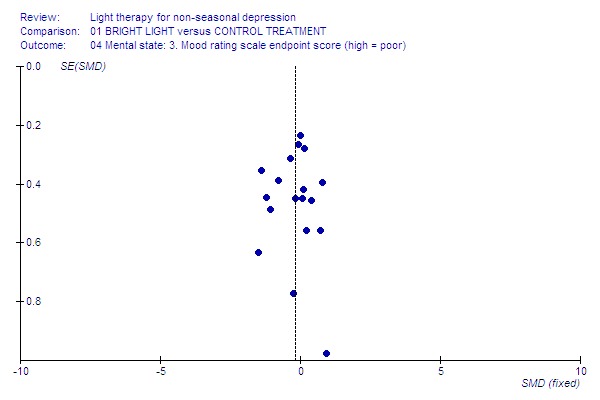

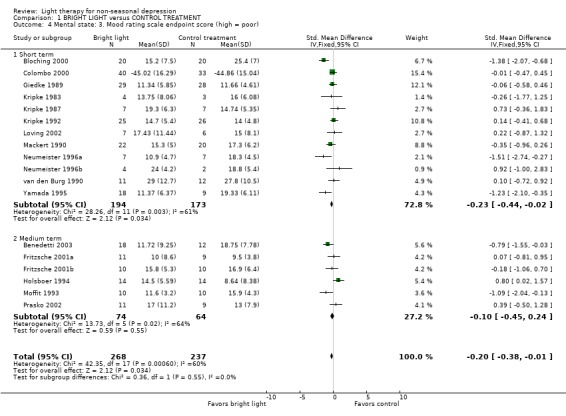

Mental state Treatment response, analyzed by primary mood rating scale endpoint scores and using a fixed effect model, was significantly better in the bright light group compared to the control treatment group (18 studies, 505 patients, standardized mean difference (SMD) ‐0.20, CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.01). A negative standardized mean difference means that the bright light group was better than the control group. This finding was mainly due to the significant benefit of short term treatment of seven days or less (12 studies, 367 patients, fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.23, CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.02). Medium term treatment did not show any significant superiority of bright light (6 studies, 138 patients, fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.10, CI ‐0.45 to 0.24). Since significant heterogeneity was found, the more conservative random effects model was also examined. According to the evaluation with this model, both short term studies and the total study effects were no longer statistically significant in favoring bright light over control treatment (short term studies: SMD ‐0.27, CI ‐0.64 to 0.10; total group: SMD ‐0.22, CI ‐0.52 to 0.09). Excluding the outlier detected in one of the short term studies (Loving 2002) had little effect on short term outcome (12 studies, 366 patients, fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.24, CI ‐0.45 to ‐0.02; random effects model: SMD ‐0.28, CI ‐0.65 to 0.09) or the all‐studies results (18 studies, 504 patients, fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.20, CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.02; random effects model: SMD ‐0.23, CI ‐0.53 to 0.08). Six studies in which the change score data of primary mood rating scales including SDs were available (Kripke 1983; Kripke 1987; Kripke 1992; Bloching 2000; Colombo 2000; Loving 2002) were also significantly in favor of bright light based on a fixed effect model but not based on a random effects model (6 studies, 198 patients; fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.35, CI ‐0.64 to ‐0.06; random effects model: SMD ‐0.46, CI ‐1.10 to 0.18).

Examining studies with clinician‐rated treatment responses showed a similar significant benefit for bright light in short term studies (9 studies, 258 patients, fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.35, CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.10) and in the total group (14 studies, 376 patients, fixed effect model: SMD ‐0.23, CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.01), whereas in the medium term studies there was no significant difference in the treatment effect between bright light and control treatment groups (5 studies, 118 patients, fixed effect model: SMD 0.04, CI ‐0.33 to 0.42). A more conservative evaluation using the random effects model was in line with previous comparisons but statistical significance was lost (short term: SMD ‐0.40, CI ‐0.90 to 0.10, the total group: SMD ‐0.23, CI ‐0.61 to 0.15). In self‐rated responses, the treatment effects of bright light and control treatments were close to equal with a fixed effect model approach (short term studies: 9 studies, 320 patients, SMD ‐0.02, CI ‐0.24 to 0.20; medium term studies: 3 studies, 68 patients, SMD ‐0.11, CI ‐0.60 to 0.37; total group: 12 studies, 388 patients, SMD ‐0.04, CI ‐0.24 to 0.17).

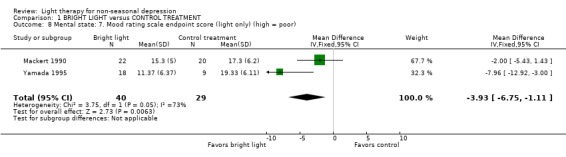

There were only two short term studies (Mackert 1990; Yamada 1995) that had applied bright light only, i.e. the patients were not exposed to sleep deprivation or other adjunctive treatments and did not receive any medication. The treatment response, evaluated by a fixed effect model, was better for bright light than for control treatment (2 studies, 69 patients, SMD ‐0.64, CI ‐1.14 to ‐0.14). With a more conservative random effects model the result was in line with a fixed effect model approach but did not reach statistical significance (SMD ‐0.73, CI ‐1.58 to 0.12).

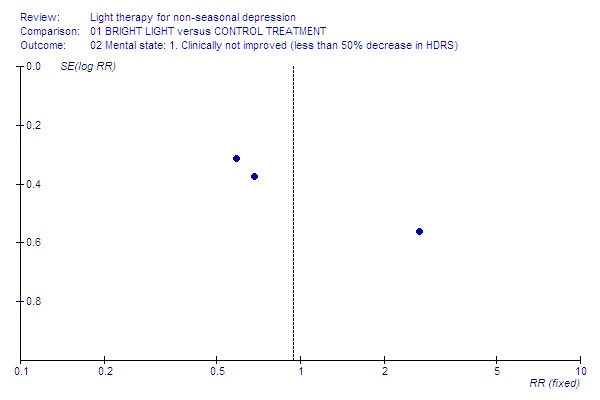

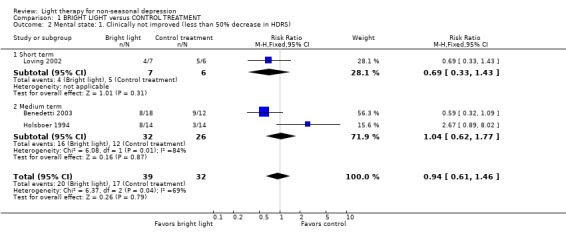

According to the criterion of 50% decrease in the HDRS score, there was no difference between groups: 20 out of 39 patients (51%) in the bright light group and 17 out of 32 patients (53%) in the control treatment group were not improved (3 studies, 71 patients, relative risk (RR) 0.94, CI 0.61 to 1.46). One study (Prasko 2002) used a more conservative criterion of the definition of improvement (50% improvement and a score less than 8). In their study sample 9 out of 13 patients (69%) in the bright light group and 7 out of 10 patients (70%) in the control treatment group were not improved.

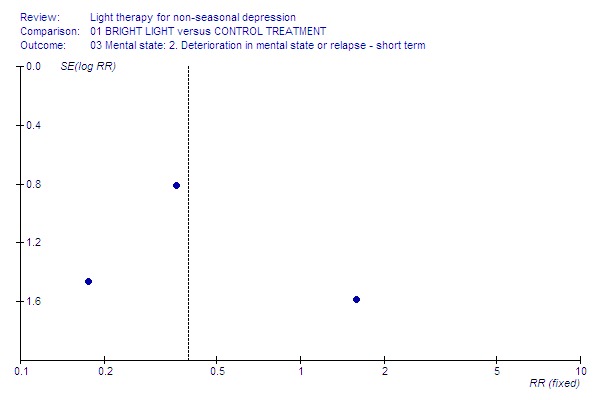

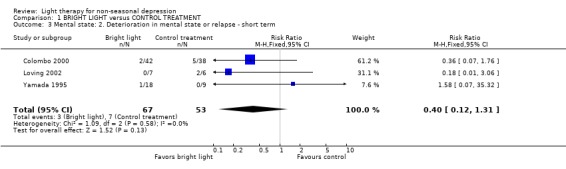

Only a few short term studies (Yamada 1995; Colombo 2000; Loving 2002) had analyzed the deterioration in mental state or relapse of the participants during treatment. These studies showed a trend of the occurrence of less deterioration/relapses in the bright light group compared to findings in the control treatment group, but the result was not statistically significant (3 studies, 120 patients, RR 0.40, CI 0.12 to 1.31). None of the medium term studies provided information on this outcome.

The baseline scores for interventions in each study are presented in Other data tables.

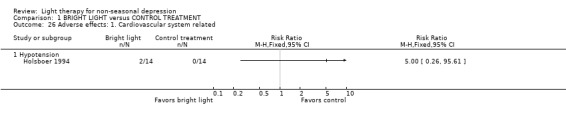

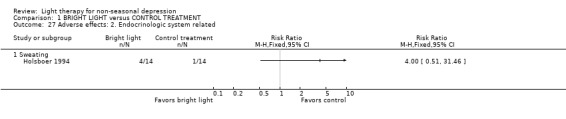

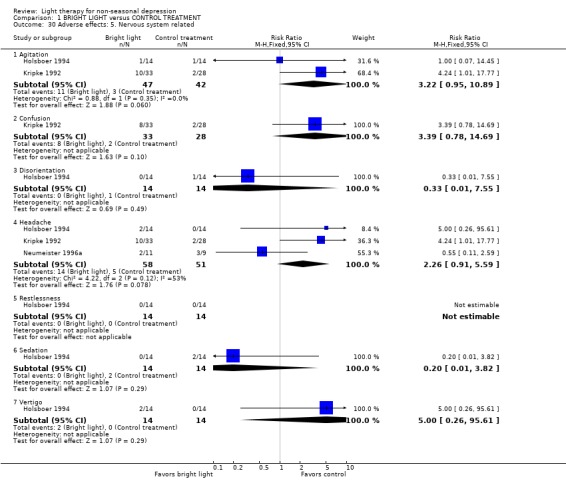

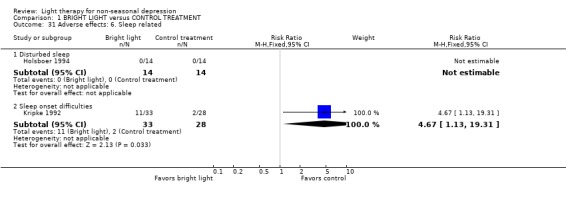

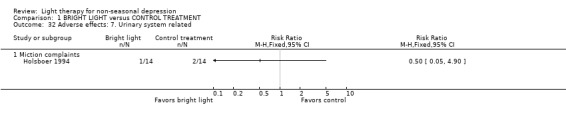

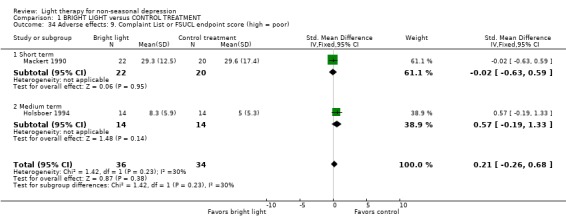

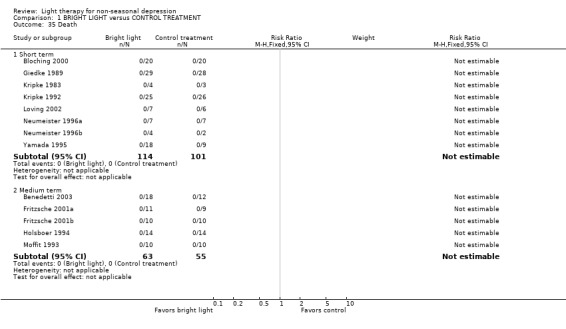

Adverse effects One study that used concomitant trimipramine drug treatment reported on adverse effects in detail (Holsboer 1994), and several other studies gave short notes on adverse effects during the study. Six studies gave information on the occurrence of mania, and in the only study that had detected patients suffering from mania (Colombo 2000), the condition was more frequent in the control treatment group. Evaluation of hypomania was reported in seven studies, in which 19 out of 118 participants in the bright light group and 3 out of 101 patients in the control group developed hypomania (7 studies, 219 patients, RR 4.91, CI 1.66 to 14.46, number needed to harm (NNH) 8, CI 5 to 20). It needs to be acknowledged that categorizing the drop‐out subjects as "failures" might overestimate the number of subjects with this adverse effect as well as with other poor outcomes. Headache was slightly more frequent in the bright light group compared to control treatment group, but did not reach statistical significance (3 studies, 109 patients, RR 2.26, CI 0.91 to 5.59). None of the patients had experienced disturbed sleep. Sleep onset difficulties were more frequent in the bright light group, although this information was reported in one study only (Kripke 1992). Agitation, headache, blurred vision and eye irritation were slightly though statistically non‐significantly more common in the bright light group than in the control group (agitation: 2 studies, 89 patients, RR 3.22, CI 0.95 to 10.89; headache: 2 studies, 109 patients, RR 2.26, CI 0.9 to 5.59; blurred vision: 2 studies, 89 patients, RR 2.22, CI 0.73 to 6.78; eye irritation: 2 studies, 68 patients, RR 3.53, CI 0.97 to 12.88). Other isolated adverse effects did not show any preference over either of the treatment groups. Two studies (Mackert 1990; Holsboer 1994) had applied a structured symptom scale for adverse effects: the short term study (Mackert 1990) did not find any significant difference between treatment groups, whereas the medium term study (Holsboer 1994) showed slightly but not statistically significantly more adverse effects in the bright light group than in the control treatment group.

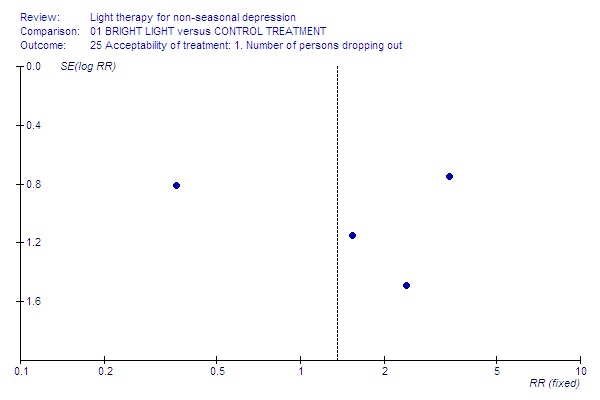

Acceptability of treatment Acceptability of treatment, analyzed by the number of patients dropping out of the study, did not show any significant difference between the groups (16 studies, 453 patients, RR 1.35, CI 0.60 to 3.07).

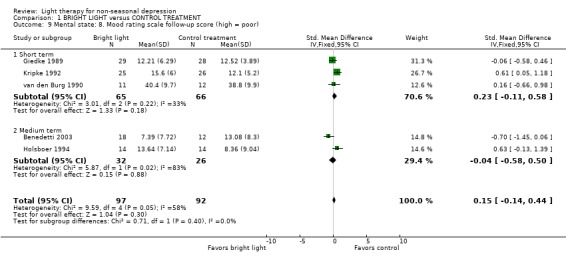

Quality of life, cost effectiveness and follow up These issues were not evaluated in the included studies. Follow up of the mood scores was evaluated in 5 studies only (Giedke 1989; van den Burg 1990; Kripke 1992; Holsboer 1994; Benedetti 2003) and it was short (between 2 days and 2 weeks). These studies did not show any statistically significant superiority of bright light over control treatment (5 studies, 189 patients, SMD 0.15, CI ‐0.14 to 0.44). Mortality No mention of mortality or permanent injuries was made in any of the studies. The studies in which all the participants had completed an assigned treatment enabled us to conclude indirectly that no deaths occurred.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses Short term results were slightly though not statistically significantly better than medium term results. As there were no long term studies available, long term and short term treatment effects could not be compared.

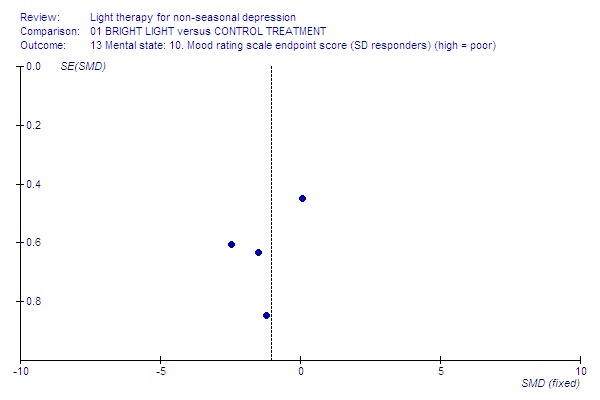

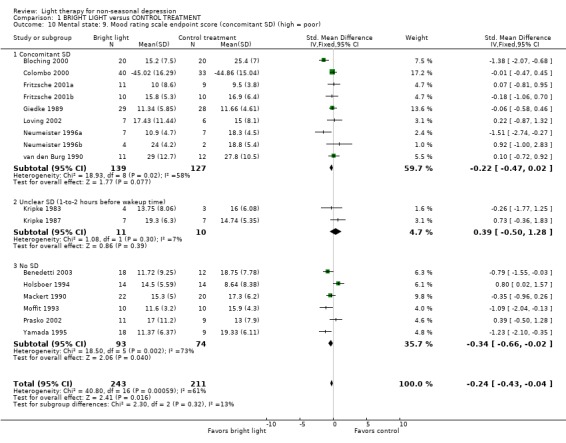

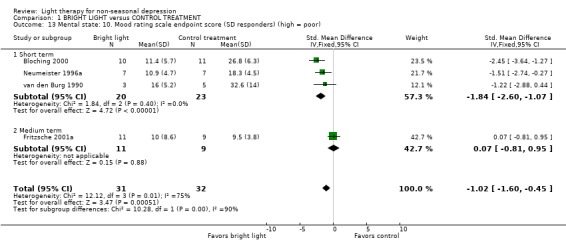

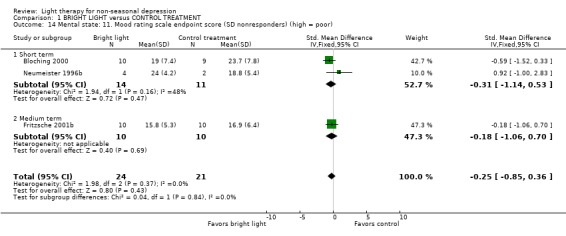

Comparison between inpatient and outpatient studies could not be performed, since there was only one study that gave outcome scores on outpatient treatment for the meta‐analysis. To evaluate the effect of sleep deprivation procedure, we created the following subgroups: concomitant sleep deprivation (9 studies, 266 patients), unclear sleep deprivation (2 studies, 21 patients), and no sleep deprivation (6 studies, 167 patients). Treatment responses between studies with patients who underwent sleep deprivation and those who did not showed that with a fixed effect model approach sleep deprivation studies showed a non‐significant trend to favor for bright light over control treatment (9 studies, 266 patients, SMD ‐0.22, CI ‐0.47 to 0.22), whereas in studies without sleep deprivation bright light was significantly better than control treatment (6 studies, 167 patients, SMD ‐0.34, ‐0.66 to ‐0.02). When a random effects model was applied with the latter group, the significance was lost (SMD ‐0.36, CI ‐0.99 to 0.26). If patients were awakened 1‐to‐2 hours before wake‐up time, there was no difference between bright light and control treatment groups based on a fixed effect model approach (2 studies, 21 patients, SMD 0.39, CI ‐0.50 to 1.28). In studies in which both bright light and sleep deprivation were applied, a fixed model approach revealed that the sleep deprivation responders had a statistically significantly better response to bright light than to control treatment (4 studies, 63 patients, SMD ‐1.02, CI ‐1.60 to ‐0.45). The result remained significant even though a more conservative random effects model was applied (SMD ‐1.24, CI ‐2.45 to ‐0.03). This finding was mainly due to short term studies (a fixed effect model approach: 3 studies, 43 patients, SMD ‐1.84, CI ‐2.60 to ‐1.07), and remained statistically significant even when a random effects model was applied (SMD ‐1.84, CI ‐2.60 to ‐1.07). In a medium term study there was no difference in response between bright light and control treatments (1 study, 20 patients, SMD 0.07, CI ‐0.81 to 0.95). The sleep deprivation non‐responders showed no significant difference in response between bright light and control treatments according to a fixed model approach (3 studies, 45 patients, SMD ‐0.25, CI ‐0.85 to 0.36).

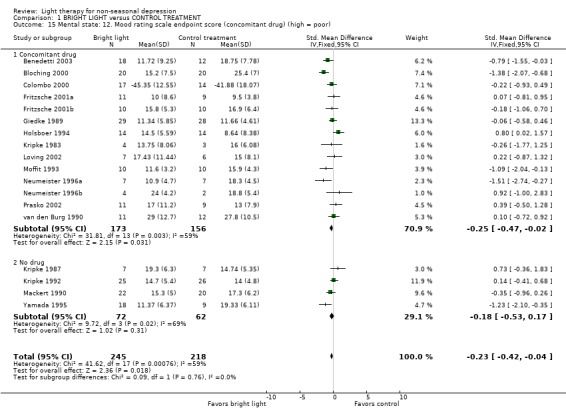

A great majority of studies had applied concomitant drug treatment (14 studies, 329 patients) whereas only a few studies had no drug treatment (4 studies, 134 patients). Evaluation of concomitant drug therapy showed that in studies with patients receiving concomitant pharmacotherapy, bright light showed a statistically significant efficacy over control treatment with a fixed effect model approach (14 studies, 329 patients, SMD ‐0.25, CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.02), but significance was lost when a random effects model was applied (SMD ‐0.24, CI ‐0.61 to 0.12). Studies with patients not receiving concomitant drug therapy showed a statistically non‐significant trend of response to bright light over control treatment (4 studies, 134 patients, SMD ‐0.18, CI ‐0.53 to 0.17).

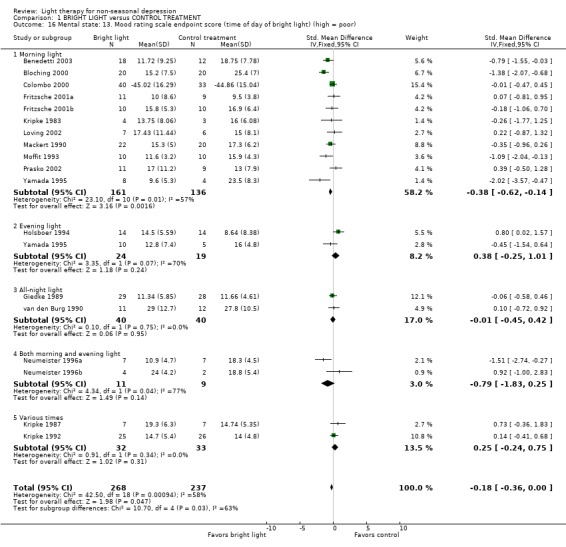

The time of the day for bright light treatment was evaluated by categorizing the studies into the following groups: morning light (11 studies, 297 patients), evening light (2 studies, 43 patients), all‐night light (2 studies, 80 patients), both morning and evening light (2 studies, 20 patients), and various times of light treatment (2 studies, 65 patients). Based on a fixed effect model approach, the effect of morning light was statistically significantly better than that of control treatment (11 studies, 297 patients, SMD ‐0.38, CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.14), whereas the treatment administered at other times of the day didn't show any superiority over control treatment. Even with a more conservative random effects model the response to morning light treatment remained statistically significantly better than the response to the control treatment (SMD ‐0.43, CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.05).

When the combination of concomitant sleep deprivation and morning bright light were evaluated, the treatment response with morning light plus concomitant sleep deprivation showed a statistically non‐significant trend for bright light over control treatment based on a fixed model approach (5 studies, 166 patients, SMD ‐0.28, SMD ‐0.59 to 0.03). Using the same fixed effect model, morning light without concomitant sleep deprivation was statistically significantly more effective than control treatment (5 studies, 124 patients, SMD ‐0.53, CI ‐0.91 to ‐0.16), and the result remained statistically significant even when a more conservative random effects model was applied (SMD ‐0.62, CI ‐1.24 to ‐0.01).

A combination of concomitant drug therapy and morning light was applied in half of the studies (9 studies, 243 patients), whereas morning light without any drug therapy was rare (2 studies, 54 patients). Evaluation of the effect of combination of concomitant drug and morning bright light showed that there was no difference between the two morning light conditions with or without pharmacotherapy. With a fixed effect model approach, both conditions were statistically significantly in favor of bright light over control treatment (combination treatment: 9 studies, 243 patients, SMD ‐0.32, CI ‐0.60 to ‐0.08; light only: 2 studies, 54 patients, SMD ‐0.57, CI ‐1.14 to ‐0.01), but with a more conservative random effects model the statistical signficance was lost (combination treatment: SMD ‐0.36, CI ‐0.79 to 0.07; light only: SMD ‐1.03, ‐2.63 to 0.58).

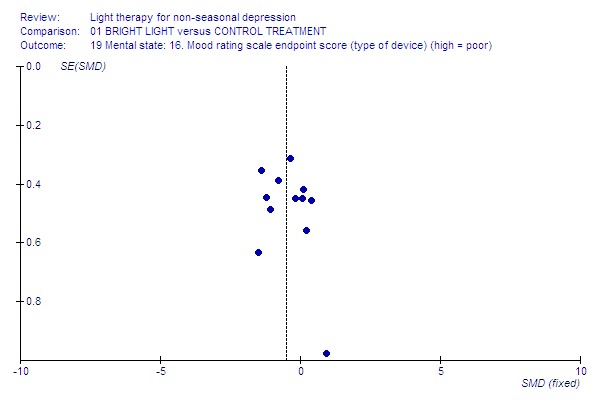

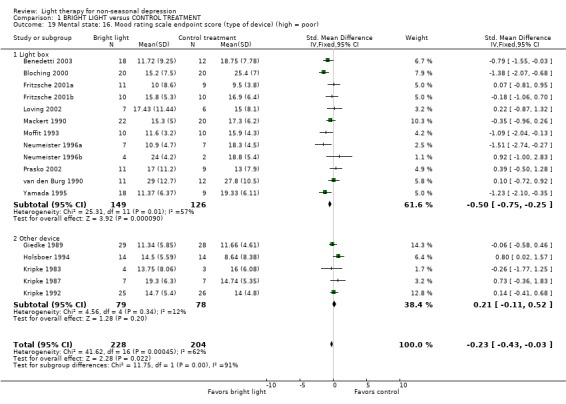

The majority of studies had used a light box (12 studies, 275 patients) whereas another device was used in only a few studies (5 studies, 157 patients). In studies using a light box, a fixed effect model approach showed that bright light was more effective than the control treatment (12 studies, 275 patients, SMD ‐0.50, CI ‐0.75 to ‐0.25), and the statistical significance remained even when a random effects model was applied (SMD ‐0.47, CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.08). If other devices, e.g. lighted rooms, were used, there was a trend for control treatment being better than light treatment but the result did not reach statistical significance (5 studies, 157 patients, SMD 0.21, CI ‐0.11 to 0.52).

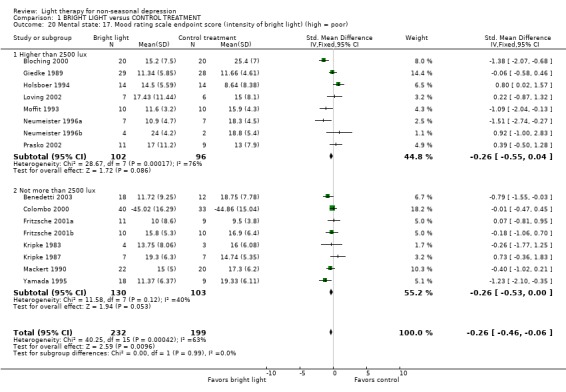

There was no difference in contrasts between bright light and control treatment groups in terms of intensity of bright light (more than 2500 lux: 8 studies, 198 patients; 2500 lux maximum: 8 studies, 133 patients) or duration of light exposure (more than one hour: 13 studies, 368 patients; one hour or less: 4 studies, 123 patients).

As only one of the two studies assessing geriatric patients could provide rating scale scores for the meta‐analysis, and none of the studies had evaluated young patients, the issue of age could not be evaluated as yet.

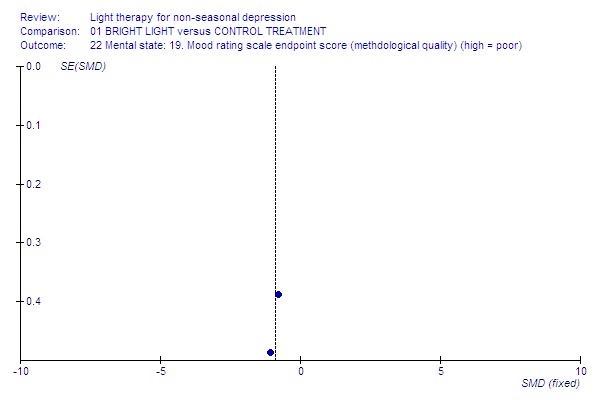

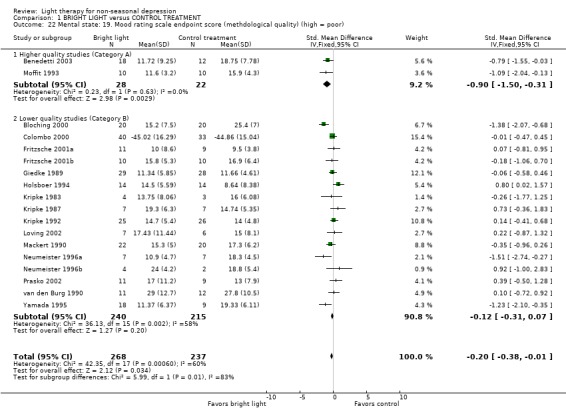

Studies with a higher methodological quality rating (category A) showed unequivocal superiority of bright light over control treatment (2 studies, 50 patients, SMD ‐0.90, CI ‐1.50 to ‐0.31), even with a more conservative random effects model approach (SMD ‐0.90, CI ‐1.50 to ‐0.31). The statistical significance of studies with lower methodological quality (category B) was weaker and did not reach statistical significance when analyzed with a fixed effect model (16 studies, 455 patients, SMD ‐0.12, CI ‐0.31 to 0.07).

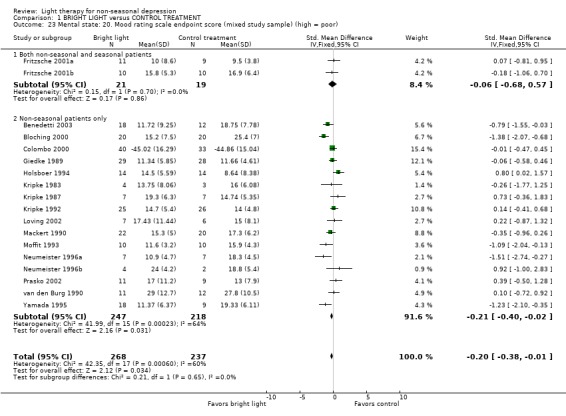

Two studies (Fritzsche 2001a, Fritzsche 2001b) had recruited a small number of seasonal patients also. The treatment response to bright light was not better in these studies than in studies that had applied non‐seasonal patients only.

Robustness of findings was tested in dichotomous outcomes in which it was assumed that drop‐outs were treatment failures. If drop‐outs of unknown reason were not considered as treatment failures, the result changed in none of the reanalyses in comparison to the primary analyses.

Patient expectations Assessment of patient expectations was reported in two studies only (Mackert 1990; Kripke 1992).

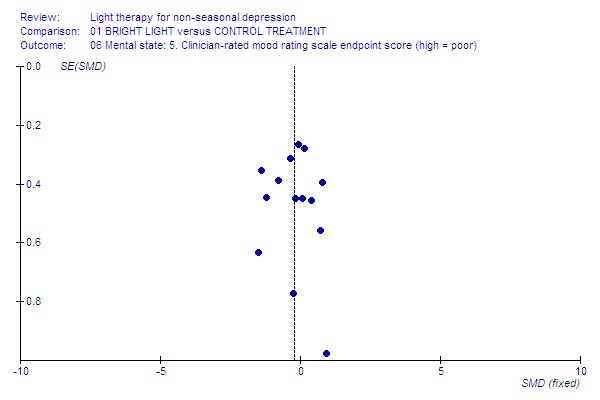

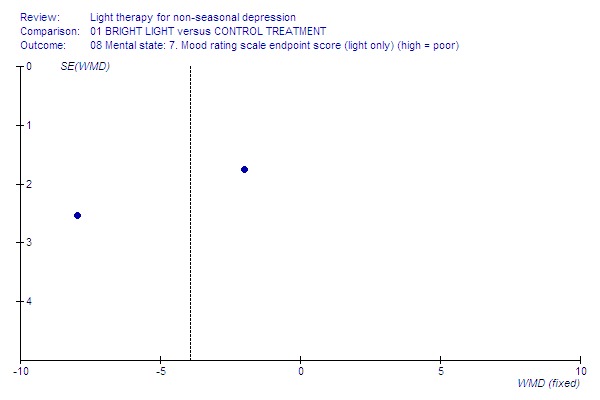

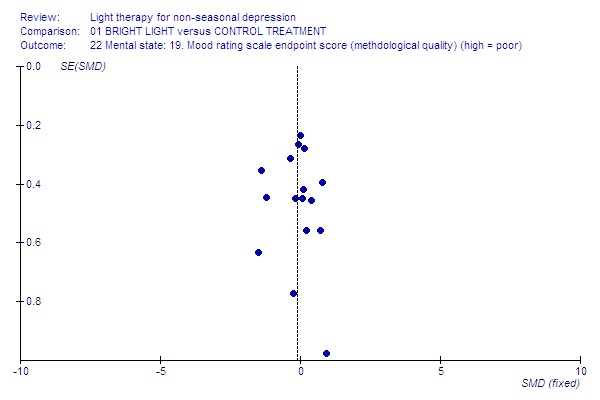

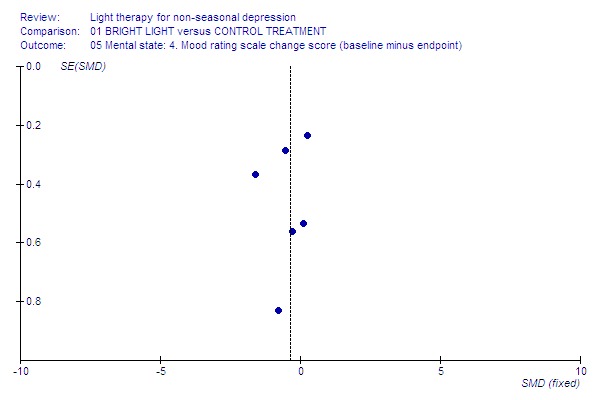

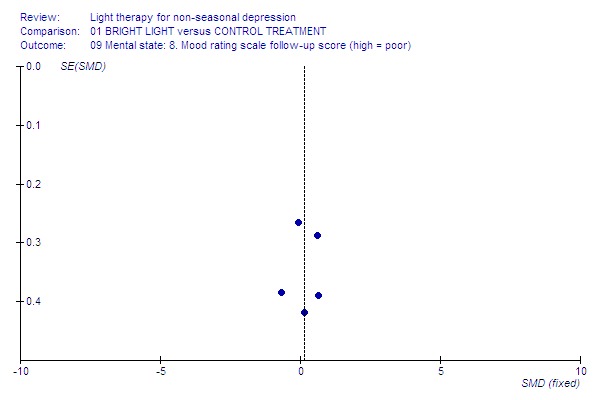

Funnel plot for publication bias In some of the comparisons with only one study it was not possible to undertake the proposed funnel plot for publication bias. For the outcomes for which the funnel plots were possible (see Additional figures in Figures Figure 1; Figure 2; Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7; Figure 8; Figure 9; Figure 10; Figure 11; Figure 12; Figure 13; Figure 14; Figure 15), visual inspection did not show any suggestion of asymmetry.

1.

Clinician‐rated.

2.

Drop‐outs.

3.

High‐quality studies.

4.

Light box.

5.

Light only.

6.

Low‐quality studies.

7.

Mood change.

8.

Mood endpoint.

9.

Mood follow‐up.

10.

Morning light.

11.

Non‐seasonals only.

12.

Not improved.

13.

Relapse.

14.

SD responders.

15.

Self‐rated.

Discussion

General comments The studies that were identified were generally of short duration, small (underpowered) and failed to report many outcomes in sufficient detail to allow pooling of all possible data.

This review benefited from extensive searches of the worldwide literature regarding light therapy as well as from personal contacts to the authors and other experts in the field. Previous research on the topic has been based on fewer studies: a recent systematic review on phototherapy for mood disorders (Gaynes 2003) had included four studies only and concluded that light was efficacious with effect sizes equivalent to those from antidepressant pharmacotherapy trials, whereas a previous meta‐analysis (Thompson 2002) had included four studies and failed to show efficacy. One more review (Kripke 1998) that had identified six studies showed that bright light treatment was effective especially as adjunctive treatment. Another major strength of our systematic review was that we only included randomized studies for non‐seasonal depression in our analysis. Light therapy for seasonal depression will be studied in a forthcoming Cochrane review.

A major problem of this meta‐analysis is that the bright light treatment studies were not fully blind. Blinding of assessment in administration of light therapy is more difficult than in studies with drug intervention, since the active treatment due to its brightness looks dissimilar to the control treatment. Subjects cannot fail to perceive the treatment and cannot be literally blind to treatment, though they may not know which is the active treatment. This might be an issue causing bias towards the benefit of active treatment. Another weakness is that for several outcomes there was either minimal or no data from high quality randomized trials. Small numbers and therefore lack of power might have made many findings being prone to type II error (a masking of a real effect), and several important hypotheses were unanswered with confidence. Many of the papers lacked important information such as details about the population, randomization procedure, and number of dropouts. Several studies were reported more than once, including preliminary results and sub‐samples with post‐hoc analysis.

The design of bright light treatment studies was very variable, and surprisingly few studies had assessed bright light as the only intervention (Mackert 1990; Yamada 1995). The number and size of trials was particularly poor for analyzing clinical global improvement, deterioriation in mental state or relapse during treatment, and adverse effects. Change scores were available in six studies and follow‐up of the outcome in five studies only.

It was possible to perform intention to treat analyses by assuming that people who left early had negative outcomes. This procedure can introduce a bias that would make the treatment arms similar if they have an equal number of dropouts, or exaggerate their divergence if they have a differential dropout rate.

Generalizability of findings Concerning the generalizability of the main results of this review, patients in the trials seemed to be similar to those seen in clinical practice, in terms of presence or absence of concurrent major depression, duration of illness, settings, and age groups.

Reporting on concealment of allocation Randomization and blindness were not well reported. The studies usually declared only randomization protocol but did not report how this procedure was performed. If blindness was declared, it was not always reported who was blind. Due to the nature of bright light treatment, it is difficult to keep patients blinded to treatment choice, even though they might have equal expectations towards active and control treatment. Very few studies had studied patients' expectations towards the treatment (Mackert 1990; Kripke 1992).

The quality of included studies was in 'category B' in all but two studies reaching 'category A' (Benedetti 2003, Moffit 1993), suggesting that even these results that are presented in this systematic review might be prone to biases and an overestimate of effect. Poor reporting of the process and outcomes of the trials was common. Some studies had to be excluded due to a lack of information about possible randomization and the number of people randomized to various treatment arms. Using a more detailed reporting would have enabled us more data for inclusion in this review.

Global impression Global status was very poorly reported, and did not show any statistically significant benefit of either treatment option over the other one.

Mental state Treatment response analyzed by primary mood rating scale endpoint scores and using a conservative statistical approach was modestly though not statistically significantly better in the bright light group compared to the control treatment group. This finding was mainly due to the result based on short term studies. Analyzing the few studies which employed the criterion of 50% decrease in the HDRS score, there was no significant difference between groups, whereas those patients that were treated with bright light showed a trend towards less deterioration in mental state or relapse during the treatment than those receiving control treatment.

Adverse effects Hypomania and sleep onset difficulties were more prevalent in patients receiving bright light treatment (showing a risk of one out of 8 patients to develop hypomania in the bright light group). Agitation, headache, blurred vision and eye irritation showed also a trend to be more prevalent in the bright light group. It needs to be considered that the study providing the most comprehensive data for adverse effects (Holsboer 1994) was evaluating bright light treatment adjunct to trimipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant with anticholinergic properties which might influence pupil size. Hence the adverse effects reported in this review might not be 'pure' effects caused by bright light itself. Also, although the study was randomized, the group receiving bright light had significantly poorer prognostic factors, such as duration of illness, at baseline. One more reason for a possible bias might be lack of reporting of adverse effects by most of the studies. Also, it needs to be acknowledged that categorizing the drop‐out subjects as "failures" might overestimate the number of subjects with adverse effects.

Acceptability of treatment Based on limited evidence from our meta‐analysis, bright light and control treatment seemed to be equally acceptable, as evidenced by the overall dropout rates from the study.

Quality of life, economic evaluation and long term studies Randomized studies assessing the quality of life of patients receiving bright light therapy or economic evaluation of the treatment were not found.

Mortality Despite the association of depression with suicide and deliberate self harm, these outcomes were not reported.

Subgroup analyses Long term evaluation studies were missing. Thus it was not possible to evaluate whether long term treatment effects differed in their results from trials evaluating short term treatment. There was a trend for studies evaluating short term effects to show a slightly more beneficial effect than studies evaluating medium term studies. These studies do indicate that bright light may be effective in as little as one week.

As only two studies (Schuchardt 1992; Loving 2002) used the outpatient setting in their study and only one of them provided outcome scores for the meta‐analysis, the inpatient versus outpatient studies were not compared.

Light therapy trials using concomitant sleep deprivation showed that bright light was more beneficial than the control treatment for sleep deprivation responders. Mainly the finding was due to short term studies. In studies with sleep deprivation nonresponders, there was no difference between bright light and control treatment groups.

There was a trend for bright light being more effective in those patients receiving concomitant drug therapy compared to the group without drug therapy, but with a more conservative approach the studies applying concomitant drug treatment lost statistical significance.

Administration of bright light in the morning showed that light treatment was more beneficial than control treatment, whereas light treatment given at other times of the day or night did not show any statistically significant benefit over the control treatment group. Morning light treatment without concomitant sleep deprivation was slightly more effective than the combination of light treatment and sleep deprivation. The efficacy of morning bright light over control treatment was equal in groups with and without concomitant drug therapy.

Trials using the light box showed that bright light treatment was more effective than control treatment compared to the results of trials using other devices.

Trials with higher intensity of light treatment (> 2500 lux) did not differ in their results from trials with lower intensity of light.

Trials with longer duration of light treatment did not differ in their results from trials with shorter duration of light, though duration and intensity may have been confounded.

Only two trials (Moffit 1993; Sumaya 2001) had studied geriatric subjects, and outcome scores of the first treatment arm were still missing in one of them; none of the trials had used very young subjects. Hence, it was not possible to evaluate whether trials using very old or very young subjects differed in their results from trials using adult subjects. However, the study with very old subjects that already has been included (Moffit 1993) did report positive results.

Based on two high quality studies only (Moffit 1993; Benedetti 2003), studies with higher methodological quality showed a more significant efficacy of bright light compared to control treatment than studies with lower methodological quality.

The treatment response to bright light was not better in two studies with both seasonal and non‐seasonal patients (Fritzsche 2001a; Fritzsche 2001b) than in studies that had applied non‐seasonal patients only.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For clinicians

Our general conclusion is that the benefit of light treatment is modest though promising for non‐seasonal depression. Although the clinical efficacy of bright light over control treatment was modest, light administered in the morning or among sleep deprivation responders was beneficial for treatment response. In general, the main effect was found in short term studies, which might indicate a more rapid action than with antidepressant drugs. A light box might be a preferable device to administer bright light. Hypomania as a possible adverse effect needs to be considered. Our findings need to be interpreted with caution, because in bright light treatment studies truly blindness is very difficult to achieve, as well as because included studies were from various settings, short and medium term only and very heterogeneous in treatment methods, patient groups, and outcomes.

A wide range of durations and intensities of bright light were applied. High versus low daily duration and intensity of light did not show any superiority over each other. It also needs to be remembered that previous research has shown that these variables are interrelated and possibly confounding, i.e., the higher the intensity, the shorter the duration is effective.

Our review covered all forms of non‐seasonal depression. The benefit of bright light in specific forms of depression and in various age groups was not possible to evaluate sufficiently. In particular, there was an absence of RCTs for more than four weeks of treatment. Long term effects of light treatment in both therapeutic and maintenance indications should be evaluated in future light treatment trials.

2. For people with depression

Bright light administered in the morning is likely to benefit in the treatment of non‐seasonal depression. Most of the studies have used it as an adjunct therapy, and especially people who respond to sleep deprivation might benefit from bright light. In general, short term effect of bright light was slightly better than longer term effect. A light box is an effective device to administer light treatment. More information is needed regarding various forms of depression, different age groups, and the therapeutic value of light for treatment and maintenance purposes.

3. For policy makers

There are no data regarding the long term effect of bright light therapy in non‐seasonal depression, or the impact of bright light on health service utilization and costs. For example, it was not possible to evaluate whether bright light treatment shortens hospital length of stay, though brighter hospital rooms have been associated with shorter duration of hospitalization in two studies (Beauchemin 1996; Benedetti 2001), which could not be included in the meta‐analysis due to variability in their interventions.

This review highlights the need for funding agencies, industry, and regulatory authorities to collaborate to ensure that future clinical trials utilize the information from previous studies on this topic. These agencies should commission or access existing evidence that closely examines treatment issues for other conditions treated with bright light. They should then ensure that this information informs the design of clinical trials at the planning stages. Such an intervention would be likely to decrease any real or perceived bias regarding the tolerability and efficacy studies of bright light in the future.

Implications for research.

The majority of existing randomized studies were short term, in‐hospital trials focusing on clinical outcomes. Short studies may underestimate both adverse effects and global efficacy.

More trials are clearly needed to assess the advantages and disadvantages of bright light treatment, especially in outpatient settings. Trials need to be of longer duration than existing ones to find out the enduring effect of bright light on both the acute symptoms and on the chronic illness and its impact on a person's life. Concurrent economic evaluations are required to assess the cost implications of this treatment in clinical practice, both for the patients themselves and the health care system.

Light trials need improvement in concealment of allocation, randomization and blinding in a rigorous manner. These procedures should be reported sufficiently to allow the critical reader to be sure that each of these potential sources of bias are dealt with. The impossibility of achieving true double‐blindness in these trials is outlined above so an honest acknowledgement of these problems will lead to more rigorous and believable research evidence. Patient expectation questionnaires should be used.

Studies should be planned to cover special target populations of non‐seasonal depression such as treatment‐resistant depression, different types of depression, first episode of depression, child and adolescent as well as old age depressive symptoms to give information on the results in each subgroup of patients. More information is needed on the timing of light as well as the benefit of adjunctive treatments such as drugs or sleep deprivation.

Bright light treatment should be evaluated by trying to find an optimal intervention for the patient in terms of time of day of bright light, duration and intensity of treatment. At least the studies of longer duration should extend to the patient's own environment where the effect and limitations caused by the treatment are more clearly seen.

Investigators should be encouraged to use widely accepted rating scales, with acceptable validity and reliability. Systematic symptom rating scales encourage researchers to report data on a continuous form, but rating scales that evaluated adverse effects are often not normally distributed and may be problematic in the data analysis. Where possible, additional use of dichotomous outcome measures is to be encouraged. Dichotomous outcomes such as relapse, discontinuation, and readmission may be of direct relevance to clinicians and policy makers. These outcome measures could be collected at no extra cost to experimenters.

Reasons for discontinuation should be reported in detail. Absence of occurrence of deaths and serious life‐threatening adverse effects should routinely be reported explicitly. 'Intention to treat' analysis should be undertaken and reported in sufficient detail to allow the reader to be sure that it is in fact what took place. 'Last observation carried forward' or other methods should be used to include the patient data of as many participants as possible into the endpoint data analysis.

The adverse effect profile is likely to affect not only safety but also longer‐term compliance and quality of life. The inclusion of outcome measures such as quality of life, satisfaction with treatment, relapse and readmission would also allow meaningful economic evaluation to be presented.

Data should preferably be presented in tables with means and standard deviations and including the actual number of patients studied. In cases where binary outcomes can be used, these should be encouraged, provided that relevant cut‐off points can be presented. Data change between baseline and endpoint stages would be informative, but endpoint scores are needed to make inter‐study comparisons more accessible.

Feedback

Feedback‐ October 2006

Summary

We noted that there was extreme heterogeneity for the lower quality studies in fig. 35, e.g. Bloching had an SMD of ‐1.38 (‐2.07 to ‐0.68), i.e. a very large, significantly beneficial effect, whereas Holsboer had an SMD of 0.80 (0.02 to 1.57), i.e. a large, significantly harmful effect. The distance between the two non‐overlapping confidence intervals is also very large, 0.70. This suggests that one of these estimates is unlikely to be correct.

We also noted that in Holsboer?s table 2, after week 5‐6, the values are given as means 14.07 and 8.54, and SDs 5.83 and 8.35, whereas you reported means 14.50 and 8.64 and SDs 5.59 and 8.38. We were unable to find the data you entered in Holsboer?s table 2.

Reply

In response to the first point made:

In our Methods section we have stated as follows:

"Although in our protocol we stated that we would only use data that met our criteria 1. and 2., during the analysis, given the scarcity of results, we decided to include also data which did not meet the criterion 2. We performed an additional sensitivity analysis to study the effect of this procedure and have indicated this in the Results section."

The funnel plot of mood endpoint scores (Fig 8) did not show any asymmetry.

In response to the second point made:

The values of the comment are obtained from one publication that states that the endpoint values are mean of week 5/ week 6 ratings. In another publication (Holsboer's thesis in German) we found the endpoint values that are obtained immediately after the cessation of light therapy, at Day 35. We preferred to use these endpoint values because in other included studies as well we have used endpoint values immediately after the end of intervention.

Contributors

Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Marić K, Tendal B Submitter agrees with default conflict of interest statement: I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2003 Review first published: Issue 2, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 January 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review is in the process of being updated. We hope to publish the updated version in Issue 2, 2008.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CCDAN editorial base for valuable help and support, especially for advice on the search strategy and the search for this review, and Professor John Geddes and Dr Kristian Wahlbeck for helpful comments on the protocol. The following colleagues have provided invaluable help in retrieving data for the review and are acknowledged: Sonia Ancoli‐Israel, Francesco Benedetti, Susan Benloucif, Benedikt Bloching, Maria Corral, Henner Giedke, Namni Goel, Siegfrid Kasper, Raymond Lam, Richard Loving, Donald Moss, Alexander Neumeister, Barbara Parry, Jan Prasko, Alexander Putilov, Martina Reide, Isabel Sumaya, Lukasz Swiecicki, Anna Wirz‐Justice, Naoto Yamada, Gina Zirpoli.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. BRIGHT LIGHT versus CONTROL TREATMENT.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global state: 1. CGI endpoint score (high = poor) ‐ medium term | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Mental state: 1. Clinically not improved (less than 50% decrease in HDRS) | 3 | 71 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.61, 1.46] |

| 2.1 Short term | 1 | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.33, 1.43] |

| 2.2 Medium term | 2 | 58 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.62, 1.77] |

| 3 Mental state: 2. Deterioration in mental state or relapse ‐ short term | 3 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.12, 1.31] |

| 4 Mental state: 3. Mood rating scale endpoint score (high = poor) | 18 | 505 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.38, ‐0.01] |