Abstract

Background

Routine use of nasogastric tubes after abdominal operations is intended to hasten the return of bowel function, prevent pulmonary complications, diminish the risk of anastomotic leakage, increase patient comfort and shorten hospital stay.

Objectives

To investigate the efficacy of routine nasogastric decompression after abdominal surgery in achieving each of the above goals.

Search methods

Search terms were nasogastric, tubes, randomised, using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Central) and references of included studies, from 1966 through Sep 2009.

Selection criteria

Patients having abdominal operations of any type, emergency or elective, who were randomised prior to the completion of the operation to receive a nasogastric tube and keep it in place until intestinal function had returned, versus those receiving either no tube or early tube removal, in surgery, in recovery or within 24 hours of surgery. Excluded will be randomised studies involving laparoscopic abdominal surgery and patient groups having gastric decompression through gastrostomy.

Data collection and analysis

Data were abstracted onto a form that assessed study eligibility, as defined above, quality related to randomizations, allocation concealment, study size and dropouts, interventions, including timing and duration of intubation, outcomes that included time to flatus, pulmonary complications, wound infection, anastomotic leak, length of stay, death, nausea, vomit ting, tube reinsertion, subsequent ventral hernia.

Main results

37 studies fulfilled eligibility criteria, encompassing 5711 patients, 2866 randomised to routine tube use, and 2845 randomised to selective or No Tube use. Patients not having routine tube use had an earlier return of bowel function (p<0.00001), a decrease in pulmonary complications (p=0.09) and an insignificant trend toward increase in risk of wound infection (p=0.39) and ventral hernia (0.09). Anastomotic leak was no different between groups (p=0.70). Vomiting seemed to favour routine tube use, but with increased patient discomfort. Length of stay was shorter when no tube was used but the heterogeneity encountered in these analyses make rigorous conclusion difficult to draw for this outcome. No adverse events specifically related to tube insertion (direct tube trauma) were reported. Other outcomes were reported with insufficient frequency to be informative.

Authors' conclusions

Routine nasogastric decompression does not accomplish any of its intended goals and so should be abandoned in favour of selective use of the nasogastric tube.

Plain language summary

Nasogastric decompression used routinely after abdominal surgery does not speed recovery.

This systematic review of 37 trials showed that routine use of nasogastric tube decompression after abdominal operations, rather than speeding recovery, may slow recovery down and increase the risk of some postoperative complications. On the other hand routine use may decrease the risk of wound infection and subsequent ventral hernia.

Background

For the past 300 years tubes have been inserted into the stomach via the nose or mouth for the purpose of evacuating gas and liquid. The reason to perform such an activity may be either therapeutic, as in patients with distention and vomiting from bowel obstruction, diagnostic, as in the case of gastrointestinal bleeding or peptic ulcer disease, or prophylactic, as in patients having major abdominal surgery. The prophylactic use of nasogastric tubes after abdominal operations, flexible tubes inserted through the nose, pharynx, oesophagus and into the stomach, has happened only in the last century, becoming so prevalent that it has been variously described as "the standard of care" (Montgomery 1996), "traditionally used by most surgeons" (Lee 2002), "common practice" (Cunningham 1992, Sakadamis 1999, Manning 2001), "unquestioned" (Savassi‐Rocha 1992), and "routine" (Wolff 1989). What is to be achieved by this prophylaxis is gastric decompression, decreased likelihood of nausea and vomit ting, decreased distention, less chance of pulmonary aspiration and pneumonia, less chance of wound separation and infection, less chance of fascial dehiscence and hernia, earlier return of bowel function, and earlier hospital discharge. Many studies have been published that assess the efficacy of this intervention. A meta‐analysis of many of the randomised and non‐randomised studies published prior to 1995 found that, though vomiting and distension were more common when nasogastric tubes were not routinely used, all other parameters of efficacy were actually better among those who did not have routine insertion and maintenance of nasogastric tubes in the post‐operative period (Cheatham 1995). This meta‐analysis needs to be updated and revised for several reasons. First, many more studies have been published since 1995, broadening the types of abdominal operations in which NGT are used; for instance to operations for gastric cancer and emergency operations for penetrating abdominal trauma. The original review also included non‐randomised studies in the meta‐analysis, introducing the potential of substantial selection bias into their results. Two more meta‐analysis have been published since then ( Lawrence 2006, Yang 2008). Yang 2008 included only RCT's that compared individuals with or without nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Time to oral diet was significantly shorter in the group which did not use nasogastric or nasojejunal tube. Other parameters like time to flatus, anastomotic leakage, pulmonary complications and length of hospital stay were similar in both groups.Lawrence 2006 looked at a lot of factors related to postoperative pulmonary complications in noncardiothoracic studies, nasogastric tube being one of them. However it used data from the previous meta analysis (Cheatham 1995) and also from our initial review. Since a good number of randomised controlled trials have been reported in this area of inquiry, these alone will form the basis of this systematic review. This is the 2010 update of the initial review and four new RCT's have been included in this (Daryaei 2009, Jiang 2007, Hsu 2007, Pessaux 2007 ).

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of prophylactic nasogastric tube decompression in the post‐operative period after major abdominal operations.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials that compare individuals with and without routine prophylactic use of nasogastric tube gastric decompression after abdominal surgery

Types of participants

Adults over the age of 18 years in whom abdominal operations have been performed of all types, such as from appendectomy to major aortovascular reconstruction, operations for gall stones, gastric cancer and emergency operations for penetrating abdominal trauma. Laparoscopic surgery will not be included in the review.

Types of interventions

The test group will have had a nasogastric tube inserted before or during surgery and maintained in place after the surgery until return of bowel function. This is an endpoint of somewhat vague character, but in general is understood to mean spontaneous passage of flatus after surgery, which usually occurs three to five days after the operation.

The control group will either have no tube inserted or a tube inserted during surgery and withdrawn either while the patient is still in the operating room, in the recovery room, when judged to be fully awake or within 24 hours of surgery.

The type of tube to be used may be a rubber Levine tube or any other tube of similar length, such a polymer tubes with sump lumena.

Patients having tubes inserted through the abdominal wall into the stomach, gastrostomy tubes, or patients with long tubes used traditionally for bowel obstruction such as Dennis tubes, Cantor tubes and Miller‐Abbott tubes will not be included in the review.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were sought for:

Time to first flatus Pulmonary complications: a composite of both atalectasis and pneumonia Fever Wound infection Length of hospital stay, or post‐operative hospital stay Wound dehiscence Anastomotic leak Incisional hernia Gastric upset in the terms of nausea and/or vomitting. This is an alteration of the first review, as three different parameters of gastric discomfort/disfunction are condensed into a single outcome: vomitting, the most commonly problem reported in this area and a more precise outcome than for instance, discomfort. Need for tube insertion/reinsertion Mortality Pain or discomfort that is tube related Adverse events related to tube insertion

Search methods for identification of studies

The following sources were searched to identify studies to be considered for this review:

MEDLINE (1966 through Sep 2009) (Appendix 1) EMBASE (1971 through Sep 2009) (Appendix 2) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library 2009 issue 3 (Appendix 3) Reference lists of published studies and reviews were scutinized. There was no limits about language, date, or other restrictions in the searches.

Major search terms: Nasogastric Tubes Randomized

Data collection and analysis

This review was undertaken initially as a classroom exercise for the Honors 201 seminar at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Undergraduate class members developed a data abstraction form (see attached Word file). Pairs of students reviewed each publication, and all identified studies were presented to the class for discussion and resolution of disagreements in data interpretation.

Study quality was assessed in each case addressing randomization method, concealment, blinding, specification of inclusions, exclusions, number of drop‐outs, intention to treat analyses and consistency of interpretations with data.

Statistical issues:

Dichotomous variables, such as wound infection, gastric upset and pulmonary complications were analyzed in Revman 5, using relative risk and the random effects model if significant heterogeneity was seen.

Continuous variables such as time to flatus or length of stay, when both means and standard deviations are presented, were assessed using the weighted mean difference in Metaview, and random effects again if significant heterogeneity is found.

When, in continuous variables, means were presented without standard deviations, we used a method for imputing standard deviations from published "p" values and "t" tables. This method was used to include those studies in the meta‐analysis. When no "p" value is presented, but findings stated simply as "significant" or "not significant", "p" values of 0.03 and 0.3 were assigned to those studies respectively.

Many studies presented median times to flatus or length of stay, often with a range and "p" value. Though these studies could not be included in the main meta‐analysis, unless the study authors supplied means and standard deviations.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the effect of studies of poor quality on overall results, to assess the effect of imputing standard deviations from p values on overall results, and to identify sources of significant heterogeneity when it arose, and to assess the robustness and consistency of statistical techniques used or developed.

Denominators in all analyses were the original number randomized, not just those completing assessment.

Study authors were contacted in order to retrieve missing data or analyses.

Results

Description of studies

37 studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria. 28 trials were identified in the first published version of this review in 2004. One of them (Otchy 1995) was a follow‐up report with a new outcome ‐ incisional hernia ‐ from a group of patients previously reported (Wolff 1989). A broad range of abdominal surgery was covered in these report, including 7 in colorectal surgery (Colvin 1986, Cunningham 1992, Olesen 1983, Ortiz 1996, Petrelli 1993, Racette 1987, Wolff 1989), 7 in gastroduodenal surgery (Adekunle 1979, Bashey 1985, Lee 2002, Miller 1972, Sitges‐Serra 1984, Wu 1994; Yoo 2002), 2 each in biliary (Edlund 1979, Hyland1982) and gynaecologic surgery (Cutillo 1999, Pearl 1996). 1 each in vascular (Friedman 1996), and emergency trauma surgery (Knoepp 1999), and finally 7 that included all facets of abdominal surgery (Cheadle 1985, Koukouras 2001, Montgomery 1996, Nathan 1991, Reasbeck 1984, Sakadamis 1999; Savassi‐Rocha 1992) . The 37 included studies encompass 5711 participants, 2866 randomized to prophylactic nasogastric tube insertion for post‐operative decompression, and 2845 randomized to no tube in the post‐operative period. Five studies were excluded after review due to reasons specified in the Table of Excluded Studies (Di Saverio 1988; Hoffmann 2001; Manning 2001; Michowitz 1988; Chung 2003). Five studies are added in this first update of the review (Carrere2006, Doglietto 2004, Lei 2004, Goueffic 2005, Zhou 2006), two involving colorectal resections (Zhou 2006, Lei 2004), two gastric resections (Carrere2006, Doglietto 2004) and one aortic reconstruction (Goueffic 2005).

Four studies have been added in this second update of the review (Daryaei 2009, Jiang 2007, Hsu 2007, Pessaux 2007 ), one involving oesophageal resection (Daryaei 2009), one hepatic resection (Pessaux 2007) and 2 involving gastric resections ( Jiang 2007, Hsu 2007).

Risk of bias in included studies

Only seven studies in the initial review specified an allocation sequence that was adequate (Adekunle 1979, Cunningham 1992, Cheadle 1985, Hyland 1980, Savassi‐Rocha 1992; Yoo 2002; Wolff 1989). In most other cases the method of randomization was not specified. In one case it was by month of birth (Miller 1972). Allocation concealment was reported in three studies (Wu 1994; Yoo 2002; Cheadle 1985). Blinding of neither participants nor observers was attempted in any study ‐ nor would it have been possible. With such a short term intervention in patients confined to hospital, drop outs should have been rare. Only four studies reported a drop out rate that was greater than 10% (Adekunle 1979; Lee 2002; Montgomery 1996; Wu 1994). Inclusion criteria were poorly specified or absent in several studies (Sitges‐Serra 1984; Miller 1972; Savassi‐Rocha 1992). Comparability of the two participant groups was difficult to assess in several studies (Koukouras 2001; Adekunle 1979; Cunningham 1992; Savassi‐Rocha 1992; Miller 1972). Perhaps the biggest quality issue is the subjectivity in reporting of the principal endpoint of the studies: return of gastrointestinal function. The meter for this was time to first flatus. This is typically reported by the patient to their surgeons to have occurred at some time prior to the ward round, which takes place first thing in the morning. There is an inherent imprecision in this measure. A way in which this imprecision could have systematically biased reporting in favor of "no tube" is not apparent (Patients with a tube may have had an incentive to report flatus in order to get rid of the tube), but it may still exist. The other primary endpoint ‐ pulmonary complications, would have been more precisely reported. Among the five studies included in the updated review (Carrere2006; Doglietto 2004; Goueffic 2005; Lei 2004; Zhou 2006), quality was generally poor with only two specifying an allocation sequence (Carrere2006; Doglietto 2004), and allocation concealment not specified in any of the five. Blinding of outcome assessment was not possible in this review. Drop outs were not a problem in any of these studies. Only one (Lei 2004) reported that the two allocation groups were not comparable at baseline.

Among the four studies included in the second update of the review (Daryaei 2009; Jiang 2007; Hsu 2007; Pessaux 2007 ), only two specified an allocation sequence (Pessaux 2007; Hsu 2007) and allocation concealment was stated only in one (Pessaux 2007 ), it was not used in one (Hsu 2007), and was not stated in the remaining two (Daryaei 2009; Jiang 2007 ). Blinding of the outcome was obviously not possible in this review. Three studies (Daryaei 2009;Pessaux 2007;Hsu 2007) had clear definitions of inclusion and exclusion criteria. However in one of these ( Hsu 2007), the randomisation appears to have been done prior to surgery despite the fact that one of the exclusion criteria was the type of surgery performed. The study participants were comparable within each study for relevant factors such as age, gender, diagnosis etc.

Effects of interventions

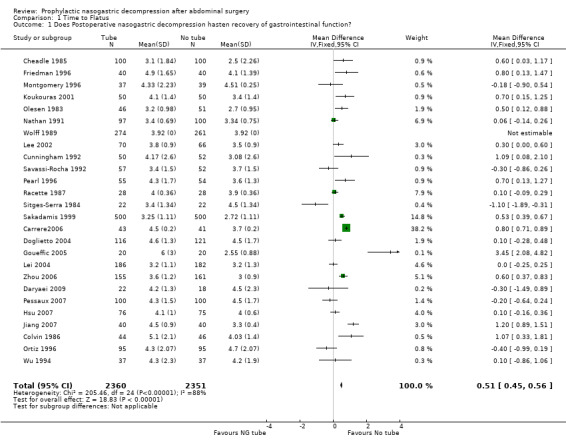

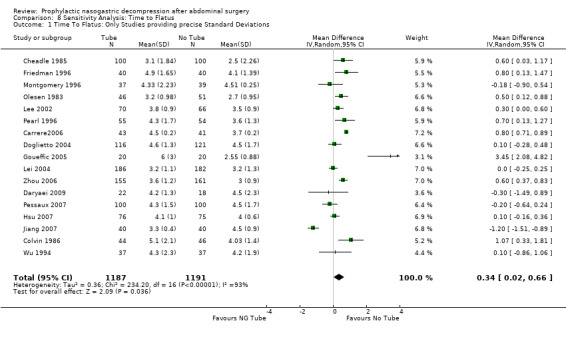

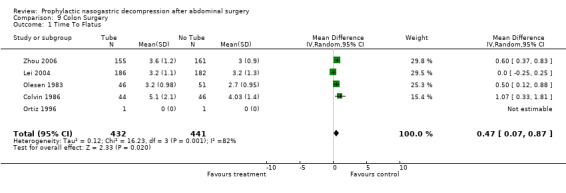

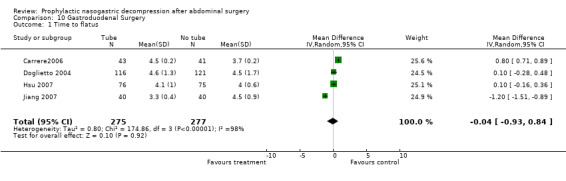

Time to Flatus: In the initial review, using only studies that provided precise standard deviations with the mean, there was a significant benefit to non‐routine use of post‐operative nasogastric decompression ‐ No Tube, though this included only 8 studies. The remainder of the studies either presented no standard deviations, using instead "p" values or global statements of "significant" or "insignificant" results. Many other studies only presented median times to return of flatus (and therefore evidence of return of gastrointestinal function) usually with "p" values. An attempt was made to include these additional studies by imputing standard deviations from the "p" values using a technique described in a Cochrane Colloquium (but not apparently published ) by Frederic Wolf and James Guevara. When results were described as "significant" a "p" value of 0.03 was assigned and for "insignificance" a "p" value of 0.3 was assigned. The broader inclusion resulted in an almost identical summary odds ratio in the meta‐analysis, though somewhat narrower confidence intervals, (Graph 1‐1) but with the introduction of significant heterogeneity. All five of the studies in the first update(Carrere2006; Doglietto 2004; Goueffic 2005; Lei 2004; Zhou 2006) provided precise standatd deviations. Nevertheless the heterogeneity they introduced was significant and only disappeared when all but (Zhou 2006) were eliminated. There were certainly some odd standard deviations in two of the studies (Carrere2006; Goueffic 2005). In all analyses, whether in the initial review using precise standard deviations or in addtion of the five studies in the update or those in which the standard deviations were inputed, there was no benefit to nasogastric suction in hastening return of gastrointestinal function as measured by time to flatus. In fact there was an opposite effect with significant benefit to no tube. None of the five added studies individually showed any benefit of prophylactic nasogastric suction in time to flatus and all five concluded it was not necessary. Looking only at patients having colon surgery and in studies providing precise standard deviations, an earlier return of bowel function was seen with "No Tube" (Graph 9‐1). In the case of gastric resections there was an insignificant benefit to No Tube in time to flatus (Graph 10‐1). There was significant heterogeneity in both analyses.

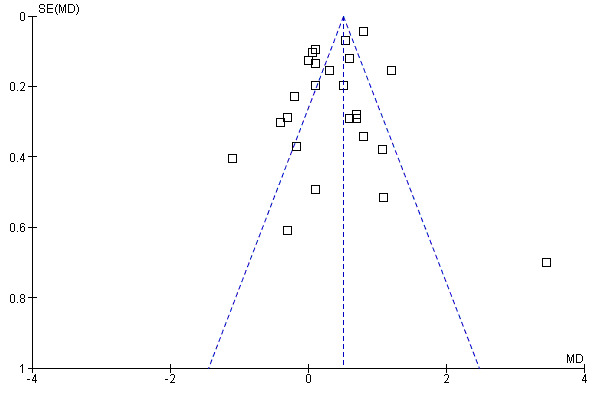

All four studies in the recent update (Daryaei 2009; Jiang 2007; Hsu 2007; Pessaux 2007 ) provided precise standard deviations. Surprisingly two of these (Daryaei 2009; Pessaux 2007 ) showed earyl return of bowel function with the tube while the other two studies (Hsu 2007; Jiang 2007)showed better results in the no tube group. However there was significant heterogeneity even prior to the addition of these four studies and it worsened with the addition of these studies. Funnel plot (Figure 1) shows slight assymetry but this is not surprising considering the presence of significant heterogeneity. All four studies in the present update however involved upper GI surgery only with Daryaei 2009 and Pessaux 2007 involving hepatic and oesophageal operations respectively, while the other two studies (Hsu 2007; Jiang 2007) involved gastric surgery. Therefore the findings for more distal GI surgery ‐ colon etc remain unchnaged.

1.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Time to Flatus, outcome: 1.1 Does Postoperative nasogastric decompression hasten recovery of gastrointestinal function?.

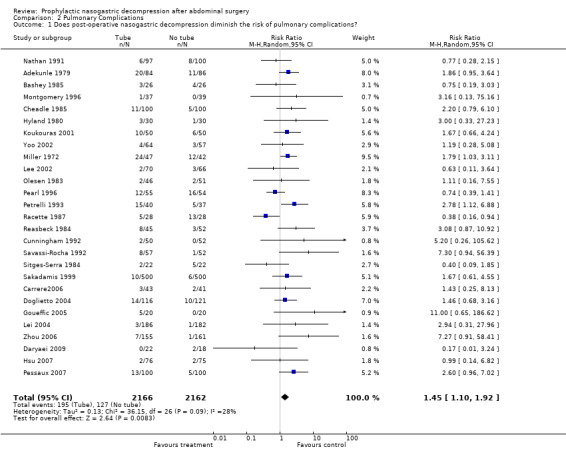

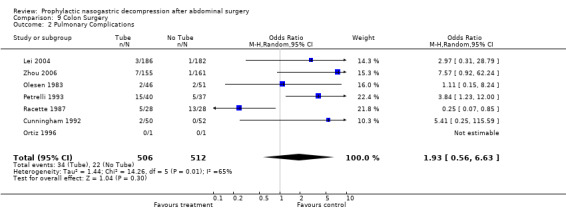

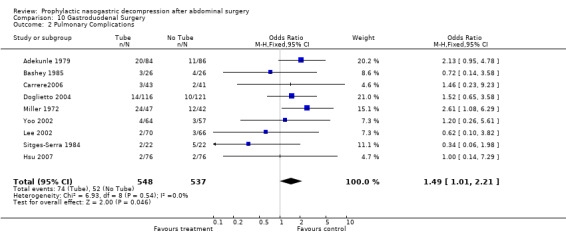

Pulmonary Complications: 27 studies reported the incidence of post‐operative pulmonary complications (an amalgam in this report of pneumonia and atalectasis) by group and the non‐routine use of nasogastric suction provided a benefit that approached statistical significance (Graph 2‐1, OR = 1.45, CI = 1.10‐1.92; ), without evidence of statistical heterogeneity. A subgroup analysis of those studies looking only at individuals with colon surgery showed no difference in pulmonary complication risk (Graph 9‐2; OR=1.93, CI=0.56‐6.63). Among those individuals have upper gastrointestinal surgery the risk of pulmonary complications was lower with No Tube, (Graph 10‐2; OR 1.49, CI 1.01‐ 2.21) with no statistical heterogeneity.

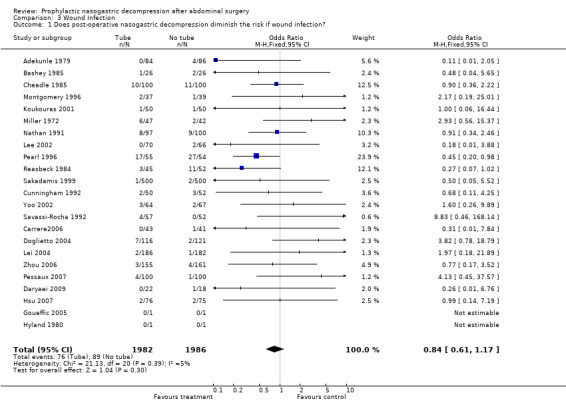

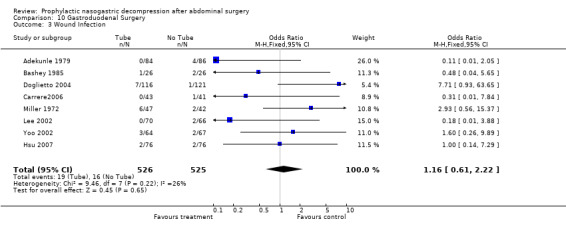

Wound Infection: 23 studies reported wound infections and the summary statistic showed that routine use of nasogastric decompression did not affect risk of wound infection, (Graph 3‐1; p=0.30), with no statistical heterogeneity. In 7 studies of those having only upper gastrointestinal surgery there was no difference in wound infection risk (Graph 10‐3; p=0.65) with no heterogeneity.

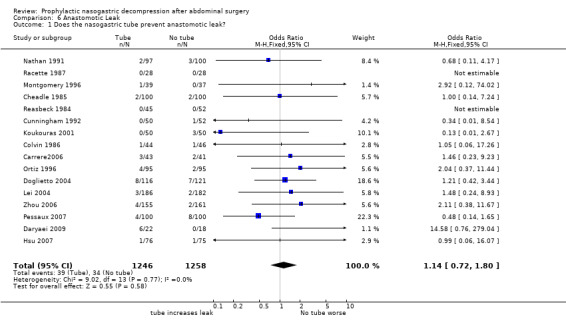

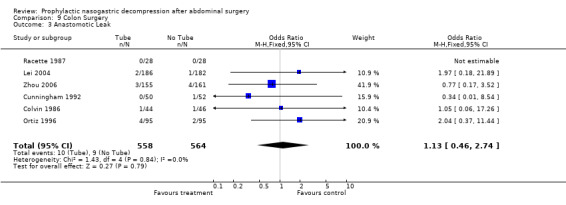

Anastomotic Leak: 13 studies reported anastomotic leak and there was no difference between groups in this outcome (Graph 6‐1; p=0.58). In 6 studies of those having only colon surgery, there was also no difference in risk of anastomotic leak between groups (Graph 9‐3; p=0.79), with no heterogeneity.

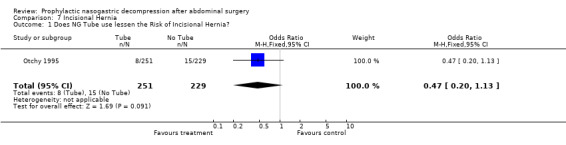

Incisional hernia: One study reported long term follow up for the development of ventral incisional hernia (Otchy 1995) and there was no difference between groups (Graph 7‐1, p=0.09).

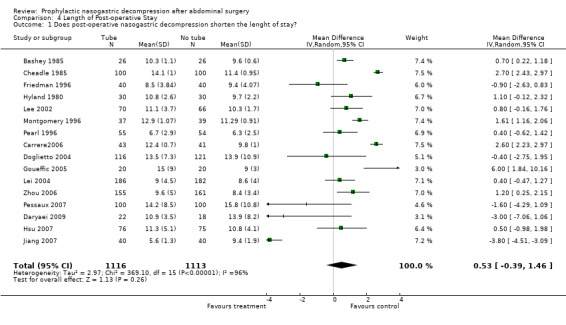

Length of Stay: 16 Studies reported mean length of stay with precise standard deviations, others with "p" values (Graph 4‐1). Other studies often presented median lengths of stay . Most showed shorter length of stay with No Tube, though significant heterogeneity was encountered in calculation of a combined effect. Sensitivity analyses done in an attempt to find a specific cause for the heterogeneity were unsuccessful in that regard.

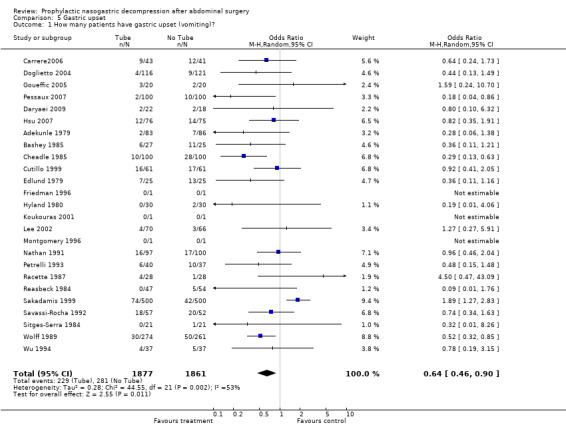

Gastric Upset: 25 Studies reported gastric upset in the post‐operative period: vomiting (Graph 5‐1). The majority showed more vomitting with No tube, but heterogeneity was encountered in the calculation of a combined effect.

Other outcomes were reported with insufficient frequency to be informative (Death, Reinsertion, Fever (often combined with Pulmonary Complications), Wound Dehiscence, and patient discomfort that is tube related). Adverse Events: Though major adverse events have been reported directly related to tube insertion, such as intracranial insertion (Gianelli 1998) or esophageal perforation (Ahmed 1998), no adverse events specifically related to tube insertion were reported in any of the included studies.

Discussion

There are three published meta‐analysis (Cheadle 1985; Lawrence 2006; Yang 2008 ). Cheatham 1995 included 26 trials of which only 16 were RCTs and even in the sensitivity analysis of higher quality trials, it included five non‐randomized trials. A very broad range of outcome measures were included. The trials that reported each of those measures were not specified. The two comparison groups were participants who had a nasogastric tube until some point in the post‐operative period in which intestinal recovery was perceived: flatus or feeding or defecation, and a group described as "selective use". This may be a more intelligent category than "no tube", since participants who needed to have a tube inserted because of vomiting or distension after surgery were therefore not treatment failures in that group but successful judgemental use of the tube. In addition, in most published RCTs, the nasogastric tube was in fact inserted in all participants in both groups but withdrawn in the latter group either in the operating room, recovery room or within 24 hours of surgery. In the selective group there was a significant risk of emesis, distention and tube insertion. In the tube group there was also a significant risk of pulmonary complications. No significant difference was seen for onset of feeding, pulmonary aspiration, wound infection, length of stay, death or overall complications. The inclusion of non‐randomized studies and lack of specificity for the outcome measures weaken this publication.

Two more meta‐analysis have been published since then ( Lawrence 2006; Yang 2008). Yang 2008 included only RCT's that compared individuals with or without nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression after gastrectomy for gastric cancer ( Doglietto 2004; Yoo 2002; Wu 1994; Lee 2002; Hsu 2007 ). Time to oral diet was significantly shorter in the group which did not use nasogastric or nasojejunal tube. Other parameters like time to flatus, anastomotic leakage, pulmonary complications and length of hospital stay were similar in both groups. Lawrence 2006 looked at a lot of factors related to postoperative pulmonary complications in noncardiothoracic studies, nasogastric tube being one of them. However it used data from the previous meta‐analysis (Cheatham 1995) and also from our initial review.

By comparison only RCTs are included in this current systematic review and its update, with more focused outcome measures and more than twice as many RCTs over a broad range of abdominal surgery are included. The biggest problem encountered in this review is the nature of reporting of the continuous outcomes: "time to flatus" and "length of stay". In many cases only "p" values were reported rather than confidence intervals for each comparison group. A method of imputing confidence intervals from p values has been presented at a Cochrane Colloquium (Wolf & Guevara; unpublished), but the use of this method introduced significant heterogeneity (comparison graphs 1‐1 and 8‐1), almost certainly due to the imprecision introduced by this technique. In addition many other RCTs reported time to flatus and length of stay using medians and "p" values rather than means and confidence intervals, precluding inclusion of these studies in the meta‐analysis. In the previous updated review significant statistical heterogeneity persisted for both these outcomes, in spite of precise standard deviations being presented in all 5 added studies. In the present update, there is again statistical heterogeneity in spite of precise standard deviations being presented in all 4 added studies. This might suggest that there is an inherent imprecision in the reporting of both these outcomes, yet they are key outcomes in the rationale for routine tube use.

Heterogeneity was not encountered in the meta‐analyses for the outcome measures: Pulmonary Complications, Wound Infection, and Anastomotic Leak supporting the validity of the findings of those comparisons. Heterogeneity persisted despite sub‐group analyses for Length of Stay, Time to Flatus and the measures of patient tolerance for the tube: Vomiting. Increased discomfort was routinely reported as more common in patients having routine use of the tube but its method of reporting was so variable that a combined effect for this outcome was not done.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Prophylactic nasogastric decompression following abdominal operations was undertaken with the intent of: 1 Hastening return of bowel function 2 By emptying the stomach, easing respiration and diminishing the risk of aspiration of gastric contents and therefore decreasing the risk of pulmonary complications 3 Increasing patient comfort, by lessening abdominal distension 4 Protect intestinal anastomoses and prevent anastomotic leakage 5 Shortening hospital stay This review has shown that the intervention is ineffective in achieving any of these goals, and in fact significant benefit may be obtained by avoidance of prolonged intubation and only selective tube insertion when needed to relieve gastric symptoms. Wound infection (and one of its most common sequellae, incisional hernia (Bucknall 1983; Yahchouchy 2003)) may be more common when routine intubation is avoided. The reasons for this are not clear. Many surgeons already avoid routine intubation. Those that don't, probably should.

Implications for research.

What don't we know? Not much. Routine use of the nasogastric tube for prophylaxis in the post‐operative period hase been abandoned in many institutions. The previous update added 5 more studies in a broad range of surgical specialties and none of them supported the routine use of a nasogastric tube. This second update added 4 more studies and none of them have shown any benefit of routine use of nasogastric tube. In regard to the primary benefits claimed for routine nasogastric decompression in the post operative laparotomy patient, this is an intervention that can, with this amount of data, be rightly abandoned. The reasons for a possible increase in wound complications without routine nasogastric decompression need to be investigated further: what specific aspects of intubation diminish these risks and what other measures might achieve the same goals, thus avoiding the adverse consequences of routine intubation.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 January 2010 | New search has been performed | Second update |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2004 Review first published: Issue 1, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 April 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

This review was undertaken as a classroom exercise in the undergraduate Honors 201 Seminar of the Honors College of the University of Illinois at Chicago. All 17 students in the class participated in creation of a data abstraction form, literature search, study allocation, data abstraction, and imputation of standard deviations.

Two of these students, Bonnie Tse and Shmaecka Edwards continued on as co‐authors of the first published version of this review but were not able to participate in the update.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

NEL 076 MEDLINE 25.09.09

1. (nasogastr* or nasojejun*).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

2. exp Intubation, Gastrointestinal/

3. 1 or 2

4. ($tube* or decompress*).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

5. (abdom* and surg*).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

6. gastrectom*.mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

7. (colo* or $operat*).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word]

8. 6 or 7 or 5

9. 8 and 4 and 3

10. randomized controlled trial.pt.

11. controlled clinical trial.pt.

12. randomized.ab.

13. placebo.ab.

14. clinical trial.sh.

15. randomly.ab.

16. trial.ti.

17. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16

18. humans.sh.

19. 17 and 18

20. 9 and 19

Appendix 2. Embase search strategy

NEL 076 Embase 25.09.09

1. (nasogastr* or nasojejun*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name]

2. exp Intubation, Gastrointestinal/

3. 1 or 2

4. *tub*/ or decompress*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name]

5. randomized controlled trial/

6. randomization/

7. controlled study/

8. multicenter study/

9. phase 3 clinical trial/

10. phase 4 clinical trial/

11. double blind procedure/

12. single blind procedure/

13. ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab.

14. (random* or cross* over* or factorial* or placebo* or volunteer*).ti,ab.

15. 10 or 7 or 11 or 13 or 6 or 12 or 8 or 5 or 14 or 9

16. "human*".ti,ab.

17. (animal* or nonhuman*).ti,ab.

18. 17 and 16

19. 17 not 18

20. 15 not 19

21. 4 and 3 and 20

Appendix 3. CLib search strategy

NEL 076 25.09.09

| ID | Search | Hits | Edit | Delete |

| #1 | nasogastr* OR nasojejun* | 883 | edit | delete |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor Intubation, Gastrointestinal explode all trees | 436 | edit | delete |

| #3 | (#1 OR #2) | 1120 | edit | delete |

| #4 | *tub* | 17539 | edit | delete |

| #5 | (decompress*) | 914 | edit | delete |

| #6 | (#4 OR #5) | 18348 | edit | delete |

| #7 | (abdom*) and (surg*) | 6791 | edit | delete |

| #8 | (gastrectom*) | 805 | edit | delete |

| #9 | (#7 OR #8) | 7489 | edit | delete |

| #10 | (#3 AND #6 AND #9) | 132 | edit | delete |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Time to Flatus.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Does Postoperative nasogastric decompression hasten recovery of gastrointestinal function? | 26 | 4711 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.45, 0.56] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Time to Flatus, Outcome 1 Does Postoperative nasogastric decompression hasten recovery of gastrointestinal function?.

Comparison 2. Pulmonary Complications.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Does post‐operative nasogastric decompression diminish the risk of pulmonary complications? | 27 | 4328 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.45 [1.10, 1.92] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Pulmonary Complications, Outcome 1 Does post‐operative nasogastric decompression diminish the risk of pulmonary complications?.

Comparison 3. Wound Infection.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Does post‐operative nasogastric decompression diminish the risk if wound infection? | 23 | 3968 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.61, 1.17] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Wound Infection, Outcome 1 Does post‐operative nasogastric decompression diminish the risk if wound infection?.

Comparison 4. Length of Post‐operative Stay.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Does post‐operative nasogastric decompression shorten the lenght of stay? | 16 | 2229 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [‐0.39, 1.46] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Length of Post‐operative Stay, Outcome 1 Does post‐operative nasogastric decompression shorten the lenght of stay?.

Comparison 5. Gastric upset.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 How many patients have gastric upset (vomiting)? | 25 | 3738 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.46, 0.90] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Gastric upset, Outcome 1 How many patients have gastric upset (vomiting)?.

Comparison 6. Anastomotic Leak.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Does the nasogastric tube prevent anastomotic leak? | 16 | 2504 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.72, 1.80] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Anastomotic Leak, Outcome 1 Does the nasogastric tube prevent anastomotic leak?.

Comparison 7. Incisional Hernia.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Does NG Tube use lessen the Risk of Incisional Hernia? | 1 | 480 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.20, 1.13] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Incisional Hernia, Outcome 1 Does NG Tube use lessen the Risk of Incisional Hernia?.

Comparison 8. Sensitivity Analysis: Time to Flatus.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time To Flatus: Only Studies providing precise Standard Deviations | 17 | 2378 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.02, 0.66] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity Analysis: Time to Flatus, Outcome 1 Time To Flatus: Only Studies providing precise Standard Deviations.

Comparison 9. Colon Surgery.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time To Flatus | 5 | 873 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.07, 0.87] |

| 2 Pulmonary Complications | 7 | 1018 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.93 [0.56, 6.63] |

| 3 Anastomotic Leak | 6 | 1122 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.46, 2.74] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Colon Surgery, Outcome 1 Time To Flatus.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Colon Surgery, Outcome 2 Pulmonary Complications.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Colon Surgery, Outcome 3 Anastomotic Leak.

Comparison 10. Gastroduodenal Surgery.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to flatus | 4 | 552 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.93, 0.84] |

| 2 Pulmonary Complications | 9 | 1085 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [1.01, 2.21] |

| 3 Wound Infection | 8 | 1051 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.61, 2.22] |

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Gastroduodenal Surgery, Outcome 1 Time to flatus.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Gastroduodenal Surgery, Outcome 2 Pulmonary Complications.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Gastroduodenal Surgery, Outcome 3 Wound Infection.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Adekunle 1979.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | duodenal ulcer surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Vomit Chest Compl. Wound Inf. UTI, death | |

| Notes | 21 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bashey 1985.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Cholecystectomy or vagotomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Vomit Chest Compl wound Inf. Length of stay Fever | |

| Notes | 23 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Carrere2006.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gastrectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus, oral intake and LOS. Vomitting, nausea discomfort, sepsis and fistula, pneumonia | |

| Notes | 32 n= 43 tube and 41 no tube. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Cheadle 1985.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Major Abdominal Surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT Cimetidine 2x2 design | |

| Outcomes | Chest Compl Wound Inf. Bloody vomit death anast. leaks | |

| Notes | 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Colvin 1986.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal Colorectal Surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT Long tube | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus Length of stay Chest Compl. leak, bleeding other GI dysf. | |

| Notes | new | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cunningham 1992.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal colorectal or small bowel surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus Vomit Cjest Compl Wound inf Anast. leak | |

| Notes | 15 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cutillo 1999.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gyne Onc. | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Vomit Time to flatus Nausea | |

| Notes | 20 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Daryaei 2009.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus pneumonia/ atelectasis vomiting wound infection anastomotic leak |

|

| Notes | n=22 tube and 18 no tube | |

Doglietto 2004.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gastrectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Leak of esophago‐jejunostomy. Time to flatus, oral intake, LOS, pneumonia, mortality, SWI | |

| Notes | 34 n=115 Tube and 120 No tube | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Edlund 1979.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Cholecystectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT drains in 2x2 design | |

| Outcomes | vomit fever | |

| Notes | 25 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Friedman 1996.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal Aortic Surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Lenght of stay Time to oral fluids Tubes replaced | |

| Notes | 13 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Goueffic 2005.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Infra‐renal arotic surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus, pneumonia, emeses, LOS, nausea, vomitting, length of ICU stay, morphine consumption | |

| Notes | 35 N=20 @ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Hsu 2007.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | gastric cancer surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus and defecation time to oral intake chest complications vomiting wound infection anastomotic leak wound dehiscence hospital stay |

|

| Notes | tube:76; no tube:75 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B‐ unclear |

Hyland 1980.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Cholecystectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Chest Compl Lenght of stay | |

| Notes | 22 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jiang 2007.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | D2 gastrectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus hospital stay duration of IV fluids |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B‐ unclear |

Knoepp 1999.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Trauma laparotomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Failure (vomit, distenton or other) length of stay | |

| Notes | 30 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Koukouras 2001.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus Chest Compl. Wound Inf. vomit nausea anast. leak UTI others | |

| Notes | 18 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lee 2002.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gastric Cancer | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus Chest Compl. Wound Inf. Nausea vomit length of stay reinsertion | |

| Notes | 10 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lei 2004.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Small or large bowel resection | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | leak, dilation, pulmonary infection, SWI, pharyngitis. Time to stool, feces, | |

| Notes | 36 n=186 tube and 181 no tube | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Miller 1972.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Vagotomy | |

| Interventions | NGT Gastrostomy no tube | |

| Outcomes | Chest Compl wound inf. dysphagia patient preference | |

| Notes | 28 rand. by month of birth | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Montgomery 1996.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT: n9o tube versus tube at surgeons discretion (18/37) plus 12 of 88 dropoouts | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus length of stay pneumonia anast. leak etc. | |

| Notes | only 19 got tubes of 88 randomized 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Nathan 1991.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus Chest compl wound inf UTI anast. leak vomit fever etc. | |

| Notes | bar graph without outliers 1 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Olesen 1983.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abd. colorectal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus nausea vomit | |

| Notes | table without specifying outliers 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ortiz 1996.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abd. colorectal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to intake Pneumonia wound inf. anast. leak UTI etc. | |

| Notes | new‐ line graph without specifying outliers new |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Otchy 1995.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | f/u of Wolff CRS | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Ventral Hernia | |

| Notes | 9** | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Pearl 1996.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gyne Onc. | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus Chest compl fever naus/vomit length of stay QOL stuff | |

| Notes | 12 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Pessaux 2007.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Liver resection | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to oral intake time to flatus chest complucations vomiting surgical wound infections anastomotic leaks duration of hospital stay |

|

| Notes | tube:100; no tube:100 | |

Petrelli 1993.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abd. colorectal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to oral intake nausea vomit fever chest compl | |

| Notes | 14 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Racette 1987.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | colon surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | chest compl naus/vomit anast. leak wound inf. | |

| Notes | 2 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Reasbeck 1984.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | GI surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | vomit Chest compl wound inf anast.leak UTI length of stay | |

| Notes | 11 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sakadamis 1999.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abdominal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus length of stay anast. leak Chest compl wound inf. nausea vomit QOL stuff | |

| Notes | 31 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Savassi‐Rocha 1992.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | GI surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to intake length of stay tube insertion | |

| Notes | 16 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sitges‐Serra 1984.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | vagotomy and pylorectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT Gastrostomy no tube | |

| Outcomes | chest compl time to intake length of stay | |

| Notes | 27 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Wolff 1989.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Abd.colorectal surgery | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus nausea vomit hernia (via otchy) | |

| Notes | 9 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Wu 1994.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gastrectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to diet naus/vomit reinsertion | |

| Notes | 7 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Yoo 2002.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Gastrectomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | time to flatus length of stay reinsertion fever naus/vomit anast. leak chest compl. wounf inf. eetc | |

| Notes | 8 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Zhou 2006.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Colorectostomy | |

| Interventions | NGT | |

| Outcomes | Time to flatus, stoo & LOS. Leak, fever, sepsis, pulmonary complications, pahrygitis | |

| Notes | 33 n=155 Tube and 161 No tube | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Akbaba 2004 | Non‐randomized study |

| Chung 2003 | Non‐randomized study |

| Di Saverio 1988 | Non randomized trial |

| Hoffmann 2001 | The study groups were nasogastric tube versus gastrostomy tube. There was no No‐tube control. |

| Kerger 2009 | Non randomized trial |

| Manning 2001 | The only outcome measured was reflux which was outside of our protocol. |

| Michowitz 1988 | No group had the nasogastric tube in place until some sign of return to bowel function ‐ all were variations of short term insertion. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Ibrahim 1977.

| Methods | not stated |

| Participants | 53 pts received nasogastric suction, 23 pts did not |

| Interventions | Postoperative nasogastric suction |

| Outcomes | not stated |

| Notes | Published in South Med J 1977; 70(9): 1070‐1 |

Contributions of authors

Rick Nelson conceived the project and led the student team, in study identification, construction of a data abstraction form, data abstraction, assessment of study quality, and performance of data anaysis. Bonnie Tse and Shamecka Edwards peformed data abstraction, imputations of standard deviations, data summaries and wrote protions of the final manuscript of the original review. However they could not be contacted at the time of second update of the review.

Rashmi Verma performed data abstraction, assessment of study quality, data analysis and wrote the final manuscript of the second update of the review.

Declarations of interest

None known

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Adekunle 1979 {published data only}

- Adekunle OO, Solanke TF, Itayemi SO, Banigo OG. Tubeless Post‐operative Care of Elective Cases of Duodenal Ulcer: A Controlled Study of 170 Cases. Afr. J. Med. 1979;8:85‐88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bashey 1985 {published data only}

- Bashey AA, Cuschieri A. Patient comfort after upper abdominal surgery. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh 1984;30(2):97‐100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carrere2006 {published data only}

- Carrere N, Seulin P, Julio CH, Blom E, Gouzi JL, Pradere B. Is nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression necessary after gastrectomy? A prospective randomized trial. World J Surg 2007;31(1):122‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cheadle 1985 {published data only}

- Cheadle WG, Vitale GC, Mackie CR, Cuschieri A. Prophylacitic Postoperative Nasogastric Decompression. Ann Surg 1985;202:361‐365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colvin 1986 {published data only}

- Colvin DB, Lee W, Eisenstat TE, Rubin RJ, Salvati EP. The Role of Nasointestinal Intubation in Elective Colonic Surgery. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 1986;5:295‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cunningham 1992 {published data only}

- Cunningham J, Temple WJ, Langevin JM, Kortbeek J. A prospective randomized trial of routine postoperative nasogastric decompression in patients with bowel anastomosis. Can J Surg 1992;35(6):629‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cutillo 1999 {published data only}

- Cutillo G, Maneschi F, Franchi M, Giannice R, Scambia G, Benedetti‐Panici P. Early Feeding Compared with Nasogastric Decompression After Major Oncologic Gynecology Surgery: A Randomized Study. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1999;93(1):41‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Daryaei 2009 {published data only}

- Daryaei P, Davari FV, Mir M, Harirchi I, Salmasian H. Omission of Nasogastric Tube Application in Postoperative Care of Oesophagectomy. World J Surg 2009;33:773‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Doglietto 2004 {published data only}

- Doglietto GB, Papa V, Tortorelli AP, Bassola M, Covino M, Pacelli F. Nasojejunal tube placement after total gastrectomy. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1309‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Edlund 1979 {published data only}

- Edlund G, Gedda S, Linden WVD. Intraperitoneal Drains and Nasogastric Tubes In Elective Cholecystectomy. The American Journal of Surgery 1979;137:775‐779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Friedman 1996 {published data only}

- Friedman SG, Sowerby SA, Pin CAD, Scher LA, Tortolani AJ. A prospective randomized study of abdominal aortic surgery without postoperative nasogastric decompression. Cardiovascular Surgery 1996;4(4):492‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goueffic 2005 {published data only}

- Goueffic Y, Rozec B, Sonnard A, Patra P, Blanoeil Y. Evidence for early nasogastric tube removal after infrarenal aortic surgery: a randomized trial. J Vasc. Surg. 2005;42:654‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hsu 2007 {published data only}

- Hsu S, Yu J C, Chen T W, Chou S J, Hsieh H F, Chan D C. Role of nasogastric tube insertion after gastrectomy. Chirurgische Gastroenterologie Interdisziplinar 2007;23(3):303‐6. [Google Scholar]

Hyland 1980 {published data only}

- Hyland JMP, Taylor I. Is Nasogastric Aspiration Really Necessary Following Cholecystectomy?. The British Journal of Clinical Practice 1980;34(10):293‐294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jiang 2007 {published data only}

- Jiang ZW, Wang ZM, Li N, Liu XX, Li XY, Zhu SH, Diao YQ, Nai YJ, Huang XJ. The safety and efficiency of fast track surgery in gastric cancer patients undergoing D2 gastrectomy [Chinese: Chung‐Hua Wai Ko Tsa Chih]. Chinese Journal of Surgery 2007 Oct 1;45(19):1314‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Knoepp 1999 {published data only}

- Knoepp LF, Thomae KR. Prospective, Randomized Evaluation of Early Removal of Nasogastric Tubes in Postceliotomy Trauma Patients. The American Surgeon 1999;65:52‐55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koukouras 2001 {published data only}

- Koukouras D, Mastronikolis NS, Tzoracoleftherakis E, Angelopoulou E, Kalfarentzos F, Androulakis J. The role of nasogastric tube after elective abdominal surgery. Clin Ter 2001;152:241‐244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2002 {published data only}

- Lee JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH. Comparison of gastric cancer surgery th versus without nasogastric decompression. Yonsei Med J 2002;43(4):451‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lei 2004 {published data only}

- Lei WZ, Zhao GP, Cheng Z, Li K, Zhou ZG. Gastrointestinal decompression after excision and anastomosis of lower digestive tract. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10(13):1998‐2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miller 1972 {published data only}

- Miller DF, Mason JR, McArthur J, Gordon I. A Randomized Prospective Trial Comparing Three Established Methods of Gastric Decompression After Vagotomy. Brit. J. Surg. 1972;59(8):605‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Montgomery 1996 {published data only}

- Montgomery RC, Bar‐natan MF, Thomas SE, Cheadle WG. Postoperative nasogastric decompression; a prospective randomized trial.. Southern Medical J. 1996;89(11):1063‐1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nathan 1991 {published data only}

- Nathan BM, Pain JA. Nasogastric suction after elective abdominal surgery: a randomized study. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 1991;73:291‐294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olesen 1983 {published data only}

- Olesen KL, Birch M, Bardram L, Burcharth F. Value of Nasogastric Tube after Colorectal Surgery. Acta Chir Scand 1983;150:251‐253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ortiz 1996 {published data only}

- Ortiz H, Armendariz P, Yarnoz C. Is early postoperative feeding feasible in elective colon and rectal surgery?. International Journal of Colorectal Disease 1996;11:119‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Otchy 1995 {published data only}

- Otchy DP, Wolff BG, Heerden JA, Ilstrup DM, Weaver AL, Winter LD. Does the avoidance of nasogastric decompression following elective abdominal colorectal surgery affect the incidence of incisional hernia. Dis. Colon & Rectum 1995;38:604‐608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pearl 1996 {published data only}

- Pearl ML, Valea FA, Fischer M, Chalas E. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Postoperative Nasogastric Tube Decompression in Gynecology Oncology Patients Undergoing Intra‐Abdominal Surgery. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1996;88:399‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pessaux 2007 {published data only}

- Pessaux P, Regimbeau M, Dondero F, Plasse M, Mantz J, Belghiti J. Randomized clinical trial evaluating the need for routine nasogastric decompression after elective hepatic resection. British Journal of Surgery 2007;94:297‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Petrelli 1993 {published data only}

- Petrelli NJ, Stulc JP, Rodriguez‐Bigas M, Blumenson L. Nasogastric Decompression following Elective Colorectal Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Study. The American Surgeon 1993;55(10):632‐635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Racette 1987 {published data only}

- Racette DL, Chang FC, Trekell ME, Farha GJ. Is Nasogastric Intubation Necessary in Colon Operations?. The American Journal of Surgery 1987;154:640‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reasbeck 1984 {published data only}

- Reasbeck PG, Rice ML, Herbison GP. Nasogastric Intubation After Intestinal Resection. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 1984;158:354‐358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sakadamis 1999 {published data only}

- Sakamandis AK, Ballas KD, Kabaroudis AG. Role of nasogastric intubation in major operations: a prospective study. Med. Sci Res. 1999;27:789‐91. [Google Scholar]

Savassi‐Rocha 1992 {published data only}

- Savassi‐Rocha PR, Conceicao SA, Ferreira JT, Diniz MTC, Campos IC, Fernandes VA, Garavini D, Castro LP. Evaluation of the routine use of the nasogastric tube in digestive operation by a prospective controlled study. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 1992;174:317‐320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sitges‐Serra 1984 {published data only}

- Sitges‐Serra A, Cabrol J, Gubern JMA, Simo J. Randomized Trial of Gastric Decompression After Truncal Vagotomy and Anterior Pylorectomy. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 1984;158:557‐560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wolff 1989 {published data only}

- Wolff BG, Pemberton JH, Heerden JA, Beart RW, Nivatvongs S, Devine RM, Dozois RR, Ilstrup DM. Elective colon and rectal surgery without nasogastric decompression. Ann. Surg. 1989;209(6):670‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wu 1994 {published data only}

- Wu CC, Hwang CR, Liu TJ. There Is No Need For Nasogastric Decompression After Partial Gastrectomy with Extensive Lymphadenectomy. Eur J Surg 1994;160:369‐373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yoo 2002 {published data only}

- Yoo CH, Son BH, Han WK, Pae WK. Nasogastric Decompression is not Necessary in Operations for Gastric Cancer: Prospective Randomised Trial. Eur J Surg 2002;168:379‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhou 2006 {published data only}

- Zhou T, Wu XT, Zhou YJ, Huang X, Fan W, Li Yc. Early removing gastrointestinal decompression and early oral feeding improve patients' rehabilitation after colorectostomy. Wrold J Gastroenterol 2006;12(15):2459‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Akbaba 2004 {published data only}

- Akbaba S, Kayaalp C, Savkilioglu M. Nasogastric decompression after total gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterol. 2004;51(60):1881‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chung 2003 {published data only}

- Chung HY, Yu W. Reevaluation of Routine Gastrointestinal Decompression after Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Hepato‐Gastroenterology 2003;50:1190‐1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Di Saverio 1988 {published data only}

- Saviero G, Bergamaschi R, Manunta A, Cecchini A, Giuliano P. [Is it necessary to use a naso‐gastric tube in cholecystectomy operations?] [E necessario l'uso del sondino naso‐gastrico negli interventi di colecistectomia?]. G. Chir. 1988;9(1):47‐48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hoffmann 2001 {published data only}

- Hoffmann S, Koller M, Plaul U, Stinner B, Gerdes B, Lorenz W, Roghmund M. Nasogastric tube versus gastrostomy tube for gastric decompression in abdominal surgery: a prospective, randomized trial comparing patients' tube‐related inconvenience. Langenbeck's Arch Surg 2001;386:402‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kerger 2009 {published data only}

- Kerger KH, Mascha E, Steinbrecher B, Frietsch T, Radke OC, Stoecklein K, Frenkel C, Fritz G, Danner K, Turan A, Apfel CC. Routine Use of Nasogastric Tubes Does Not Reduce Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Ambulatory Anesthesiology Sep2009;109(3):768‐773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manning 2001 {published data only}

- Manning BJ, Winter DC, McGreal G, Kirwan WO, Redmond HP. Nasogastric intrubation causes gastroesophagel reflux in patients undergoing elective laparotomy. Surgery 2001;130(5):788‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Michowitz 1988 {published data only}

- Michowitz M, Chen J, Waizbard E, Bawnik JB. Abdominal Operations Without Nasogastric Tube Decompression of the Gastrointestinal Tract. The American Surgeon 1988;54:672‐675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Ibrahim 1977 {published data only}

Additional references

Ahmed 1998

- Ahmed A, Aggarwal M, Watson E. Esophageal perforation: a complication of nasogastric tube insertion. Am J Emerg. Med 1998;16(1):64‐66. [9451317] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bucknall 1983

- Bucknall TE, Cox PJ, Ellis H. Brust Abdomen and incisional hernia: a prospective study of 1129 major laparotomies. Brit. Med. J 27 March, 1982;284(6320):931‐933. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cheatham 1995

- Cheatham ML, Chapman WC, Key SP, Sawyers JL. A meta‐analysis of selective versus routine nasogastric decompression after elective laparotomy. Annals of Surgery 1995;221(5):469‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gianelli 1998

- Gianelli Castiglioni A, Bruzzone E, Burrello C, Pisani R, Ventura F, Canale M. Intracranial insertioon of a nasogastric tube in a case of homicidal head trauma. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19(4):329‐334. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lawrence 2006

- Lawrence VA, Cornell JE, Smetana GW. Strategies to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications after noncardiothoracic surgery. Annals of Internal Medicine Apr 2006;144(8):596‐608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yahchouchy 2003

- Yahchouchy‐Chouillard E, Aura T, Picone O, Etienne JC, Fingerhut A. Incisional Hernias. Digestive Surgery 2003;20:3‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yang 2008

- Yang Z, Zheng Q, Wang Z. Meta‐analysis of the need for nasogastric or naso jejunal decompression after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. British Journal of Surgery 2008;95:809‐816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]