Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms, often of substantial severity, are found in 50% of newly diagnosed suffers of schizophrenia and 33% of people with chronic schizophrenia who have relapsed. Depression is associated with dysphoria, disability, reduction of motivation to accomplish tasks and the activities of daily living, an increased duration of illness and more frequent relapses.

Objectives

To determine the clinical effects of antidepressant medication for the treatment of depression in people who also suffer with schizophrenia.

Search methods

We undertook electronic searches of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (October 2000), ClinPsych (1988‐2000), The Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2000), EMBASE (1980‐2000) and MEDLINE (1966‐2000). This was supplemented by citation searching, personal contact with authors and pharmaceutical companies.

We updated this search January 2013 and added 71 new trials to the awaiting assessment section.

Selection criteria

All randomised clinical trials that compared antidepressant medication with placebo for people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were also suffering from depression.

Data collection and analysis

Data were independently selected and extracted. For homogeneous dichotomous data the fixed effects risk difference (RD), the 95% confidence intervals (CI) and, where appropriate, the number needed to treat (NNT) were calculated on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, reviewers calculated weighted mean differences. Statistical tests for heterogeneity were also undertaken.

Main results

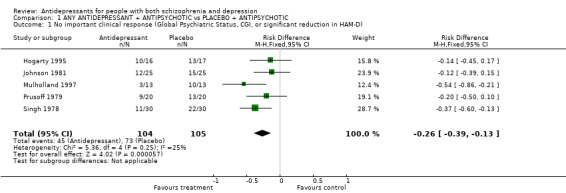

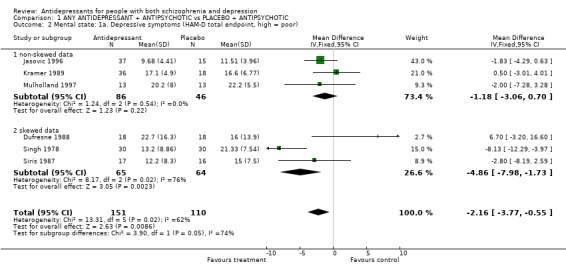

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. All were small, and randomised fewer than 30 people to each group. Most included people after the most acute phase of psychosis and investigated a wide range of antidepressants. The quality of reporting varied a great deal. For the outcome of 'no important clinical response' antidepressants were significantly better than placebo (n=209, 5 RCTs, summary risk difference fixed effects ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.13, NNT 4 95% CI 3 to 8). The depression score at the end of the trial, as assessed by the Hamilton Rating Scale (HAM‐D), seemed to suggest that using antidepressants was beneficial, but this was only statistically significant when a fixed effects model was used (n=261, 6 RCTs, WMD fixed effects ‐2.2 95% CI ‐3.8 to ‐0.6; WMD random effects ‐2.1 95% CI ‐5.04 to 0.84). There was no evidence that antidepressant treatment led to a deterioration of psychotic symptoms in the included trials. Heterogeneous data on 'any adverse effect' are equivocal (n=110, 2 RCTs, RD fixed 0.11 CI ‐0.03 to 0.25, Chi square 7.5, df=1, p=0.0062). In one small study extrapyramidal adverse effects were reported less often by those allocated to antidepressant (n=52, 1 RCT, RD fixed ‐0.28 CI ‐0.5 to ‐0.04). Only about 10% of people left these studies by 12 weeks. There was no apparent difference between those allocated placebo and those given an antidepressant (n=426, 10 RCTs, RD fixed 0.04 CI ‐0.02 to 0.1).

Authors' conclusions

Overall, the literature was of poor quality, and only a small number of trials made useful contributions. Though our results provide some evidence to indicate that antidepressants may be beneficial for people with depression and schizophrenia, the results, at best, are likely to overestimate the treatment effect, and, at worst, could merely reflect selective reporting of statistically significant results and publication bias.

At present, there is no convincing evidence to support or refute the use of antidepressants in treating depression in people with schizophrenia. We need further well‐designed, conducted and reported research to determine the best approach towards treating depression in people with schizophrenia.

Note: the 71 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

Keywords: Humans; Antidepressive Agents; Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use; Antipsychotic Agents; Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use; Chemotherapy, Adjuvant; Depression; Depression/complications; Depression/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Schizophrenia; Schizophrenia/complications; Schizophrenia/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Antidepressants for people with both schizophrenia and depression

Depression is common in people with schizophrenia and is associated with substantial problems including an increased risk of suicide. Many clinicians use antidepressant drugs in addition to anti‐psychotics in order to treat depression. This review identified eleven randomised controlled trials that compared antidepressants with a placebo in people with schizophrenia who also had depression. There was some evidence that antidepressants did lead to an improvement in global outcome, but the small number of studies providing usable data and their poor quality, suggest that this evidence should be interpreted with caution. At present, there is no convincing evidence either to support or refute the use of antidepressants in treating depression in people with schizophrenia. Further well‐designed, conducted and reported research is needed in this area.

Background

It is now widely recognised that depressive symptoms, often of substantial severity, are found in those whose main diagnosis is schizophrenia (Plasky 1991). This 'co‐morbidity' has been found to exist in 50% of newly diagnosed suffers of schizophrenia and 33% of people with chronic schizophrenia who have relapsed (Johnson 1981). Martin 1985, from data collected in the large St. Louis 500 Study, suggested that 60% of people with schizophrenia also have depression.

Depressive symptomatology in schizophrenia is important for a number of reasons. It is associated with dysphoria and disability and reduces motivation to accomplish tasks and the activities of daily living. Depressive symptoms are associated with an increased duration of illness and more frequent relapses (Mulholland 2000). There is also evidence that the suicide risk in people with schizophrenia is associated with depressive symptoms. Miles 1977 found that 10% of people suffering from schizophrenia committed suicide and Roy 1986 that 57% of people with schizophrenia who commit suicide had also been depressed. Effective treatment of depressive symptomatology in schizophrenia should therefore lead to improvement in health, quality of life and reduce suicide risk. For these reasons it is common clinically to use antidepressants in addition to any antipsychotic medication. Psychological and social approaches towards the treatment of depression should also be considered but are not part of this review.

There are considerable problems in attempting to define depressive symptomatology in schizophrenia. Firstly there is the potential to confuse the negative symptoms of apathy, blunted affect and withdrawal, seen in schizophrenia, with depression. Secondly it is easy to confuse the extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and other adverse effects that occur with most conventional drug treatments for schizophrenia with depressive signs and symptoms. For example, akathisia, hypokinesia and sedation are similar to some of the symptoms of depression. 'Antimuscarinic' drugs (or anti‐cholinergic drugs) can reduce EPS in those treated with antipsychotics (Siris 1987a, Mulholland 2000). Tricyclic antidepressants, however, have 'antimuscarinic' side effects that might reduce these EPS and this can also be a problem in interpreting the results from trials. For these reasons it is important to be clear about eliciting the signs and symptoms of depression within schizophrenia. As a general rule, structured assessments and clear criteria for diagnosing depression lead to more confidence in establishing depressive symptoms. Certainly, some authors have suggested that specific diagnostic criteria should be used (Plasky 1991, Martin 1985). Optimal management of antipsychotic and anticholinergic medication is also essential before assessing depression in people with schizophrenia.

There is a further important aspect that has to be considered. The symptoms of depression are quite common in acute episodes of schizophrenia and, in general, these improve in parallel with the improvement in the psychosis (Knights 1981). Kramer 1989 suggests that tricyclic antidepressant drugs are ineffective during this acute phase of illness, and may even worsen the psychosis. On the other hand, Siris 1987b suggests that, if someone is in the post‐psychotic phase of treatment, an adjunctive anti‐depressant might be effective, provided the psychosis is well controlled by neuroleptics. There is now some degree of clinical consensus that treatment of depressive symptoms should be after the acute psychosis has been resolved. The term post‐psychotic depression has been used, though this term has been criticised for ignoring the depressive symptoms commonly found during the acute psychosis (Knights 1981).

Objectives

To determine whether antidepressant medication, as an adjunct to antipsychotic drugs, has clinically meaningful benefits for people with schizophrenia who also have clinically significant depression.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

People suffering from schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, diagnosed by any criteria, who had also had a depressive episode, diagnosed in any way.

Types of interventions

1. Antidepressant medication: any dose. Any antidepressant that has been licensed for use, even if subsequently withdrawn, was included.

There are a number of different classes of antidepressant drugs. The groupings in this review are those published in the British National Formulary (section 4.1): · tricyclic and related drugs; · monoamine‐oxidase inhibitors (MAOI's); · selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitors (SSRI) and related drugs; · other antidepressant drugs.

It is difficult to acquire a definitive list of all antidepressants but a list is provided in order to facilitate identification of compounds.

Amesergide, amineptine hydrochloride, amitriptyline, amoxapine, benactyzine hydrochloride, brofaromine, bupropion hydrochloride, butriptyline hydrochloride, cianopramine, citalopram hydrobromide, clomipramine hydrochloride, clorgyline hydrochloride, clovcxamine, demexiptiline hydrochloride, desipramine hydrochloride, dibenzepin hydrochloride, dimetacrine tartrate, dothiepin hydrochloride, doxepin hydrochloride, etoperidone hydrochloride, femoxetine, fezolamine fumarate, fluoxetine hydrochloride, fluvoxamine maleate, ifoxetine, imipramine hydrochloride, iprindole hydrochloride, iproniazid phosphate, isocarboxazid, levoprotiline, lofepramine hydrochloride, maprotiline hydrochloride, medifoxamine, melitracen hydrochloride, metapramine fumarate, mianserin hydrochloride, milnacipran, minapri hydrochloride, mirtazapine, moclobemide, nefazodone hydrochloride, nialamide, nomifensine maleate, nortriptyline hydrochloride, opipramol hydrochloride, oxaflozane hydrochloride, oxaprotiline hydrochloride, oxitriptan, paroxetine hydrochloride, phenelzine sulphate, pirlindole, propizepine hydrochloride, protriptyline hydrochloride, quinupramine, rolipram, rubidium chloride, sertraline hydrochloride, setiptiline, sibutramine, teniloxazine, tianepine sodium, tofenacin hydrochloride, toloxatone, tranylcypromine sulphate, trazadone hydrochloride, trimipramine, tryptophan, venlafaxine hydrochloride, viloxazine hydrochloride, viqualine, zimelidine hydrochloride.

2. Placebo or active placebo (one that is known not to have antidepressant properties, but effects that mimic the adverse effects of antidepressants).

It was expected that everyone in the studies would also be receiving antipsychotic medication and possibly an anticholinergic.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes of interest were:

1. Death ‐ suicide or natural causes.

2. Leaving the study early or drop‐outs.

3. Clinical response: 3.1 Clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies; 3.2 Average score/change in global state; 3.3 Clinically significant response on psychotic symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies; 3.4 Average score/change on psychotic symptoms; 3.5 Clinically significant response on depressive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies*; 3.6 Average score/change in depressive symptoms.*

4. Extrapyramidal side effects: 4.1 Use of anticholinergic drugs; 4.2 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies; 4.3 Average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects.

5. Other adverse effects, general and specific

6. Service utilisation outcomes: 6.1 Hospital admission. 6.2 Days in hospital.

7. Economic outcomes

8. Quality of life / satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers: 8.1. Significant change in quality of life / satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies; 8.2 Average score / change in quality of life / satisfaction.

All outcomes, when available, were reported for the short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13‐26 weeks), and long term (over 26 weeks).

Search methods for identification of studies

1. Electronic searching

1.1. ClinPsych (SilverPlatter ASCII 3.0 DOS 1988‐6/00) was searched using the phrase:

[(random* or ((singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) near (blind* or mask*)) or ((clin* near trial*) in ti, ab) or placebo*) and (schizo* or hebephreni* or oligophreni* or (psychotic* or psychos?s)) and (antidepressant* or tricyclic* or ssri or amesergide or amineptine or amitriptyline or amoxapine or benactyzine or brofaromine or bupropion or butriptyline or cianopramine or citalopram or clomipramine or clorgyline or clovoxamine or demexiptiline or desipramine or dibenzepin or dimetacrine or dothiepin or doxepin or etoperidone or femoxetine or fezolamine or fluoxetine or fluvoxamine or ifoxetine or imipramine or iprindole or iproniazid or isocaroxazid or levoprotiline or lofepramine or maprotiline or medifoxamine or melitracen or metapramine or mainserin or milnacipran or minapri or mirtzapine or moclobemide or nefazodone or nialamide or nomifensine or nortriptyline or opipramol or oxaflozane or oxaprotiline or oxitriptan or paroxetine or phenelzine or pirlindole or propizepine or protriptyline or quinupramine or rolipram or rubidium or sertraline or setiptiline or sibutramine or teniloxazine or tianepine or tofenacin or toloxatone or tranycypromine or trazodone or tripramine or tryptophan or venlafaxine or viloxazine or viqualine or zimeldine or depres*)]

1.2 Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2000) was searched using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's (CSG) phrase for randomised controlled trials (see Group search strategy) combined with the phrase:

[exp antidepressive agents/ or exp antidepressive agents, tricyclic/ or exp amitriptyline/ or exp fluoxetine/ or exp imipramine/ or exp antidepressive agents, second‐generation/ or exp serotonin antagonists/ or exp guanosine/ or exp or nortriptyline/ or exp serotonin uptake inhibitors/ or exp paroxetine/ or amesergide/ or amineptine/ or amoxapine/ or benactyzine/ or brofaromine/ or bupropion/ or butriptyline/ or cianopramine/ or citalopram/ or clomipramine/ or clorgyline/ or clovoxamine/ or demexiptiline/ or desipramine/ or dibenzepin/ or dimetacrine/ or dothiepin/ or doxepin/ or etoperidone/ or femoxetine/ or fezolamine/ or fluvoxamine/ or ifoxetine/ or iprinodole/ or iproniazid/ or isocarboxazid/ or levoprotiline/ or lofepramine/ or maprotiline/ or medifoxamine/ or melitracen/ or metapramine/ or milnacipran/ or minapri/ or mirtzapine/ or moclobemide/ or nefazodone/ or nialamide/ or nomifensine/ or nortriptyline/ or opipramol/ or oxaflozane/ or oxaprotiline/ or hydroxytryptophan/ or phenelzine/ or pirlindole/ or propizepine/ or protriptyline/ or quinupramine/ or rolipram/ or rubidium/ or sertraline/ or setiptiline/ or sibutramine/ or teniloxazine/ or tianepine/ or tofenacin/ or tranylcypromine/ or trazodone/ or tripramine/ or tryptophan/ or venlafaxine/ or viloxazine/ or viqualine/ or zimeldine/]

1.3 Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (October 2000) was searched using the following phrase:

[antidepressant* or tricyclic* or ssri or amesergide or amineptine or amitriptyline or amoxapine or benactyzine or brofaromine or bupropion or butriptyline or cianopramine or citalopram or clomipramine or clorgyline or clovoxamine or demexiptiline or desipramine or dibenzepin or dimetacrine or dothiepin or doxepin or etoperidone or femoxetine or fezolamine or fluoxetine or fluvoxamine or ifoxetine or imipramine or iprindole or iproniazid or isocaroxazid or levoprotiline or lofepramine or maprotiline or medifoxamine or melitracen or metapramine or mainserin or milnacipran or minapri or mirtzapine or moclobemide or nefazodone or nialamide or nomifensine or nortriptyline or opipramol or oxaflozane or oxaprotiline or oxitriptan or paroxetine or phenelzine or pirlindole or propizepine or protriptyline or quinupramine or rolipram or rubidium or sertraline or setiptiline or sibutramine or teniloxazine or tianepine or tofenacin or toloxatone or tranycypromine or trazodone or tripramine or tryptophan or venlafaxine or viloxazine or viqualine or zimeldine or depres* or #42=476 or #42=451 or #42=23 or #42=430 or #42=67 or #42=65 or #42=16 or #42=181 or #42=236 or #42=166 or #42=433 or #42=165 or #42=512 or #42=389 or #42=410 or #42=633 or #42=608 or #42=646]

(#42 is the field of this Register containing intervention‐specific codes).

1.4 EMBASE (1980 ‐ Oct 2000) was searched using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's search strategy for trials relating to those with schizophrenia (see Group Module) combined with the phrase:

[and exp antidepressant agent/ or exp tricyclic antidepressant agent/ or exp imipramine/ or exp amitriptyline/ or depression/ or psychotropic agent/ or maio.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or exp serotonin uptake inhibitor/ or ssri.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or amineptine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or amesergide.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or amitriptyline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or amoxapine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or benactyzine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or brofaromine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or bupropion.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or butriptyline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or cianopramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or citalopram.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or clomipramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or clorgyline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or clovoxamine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or demexiptiline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or desipramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or dibenzepin.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or dimetacrine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or dothiepin.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or doxepin.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or etoperidone.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or femoxetine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or fezolamine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or fluoxetine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or fluvoxamine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or ifoxetine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or imipramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or iprindole.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or iproniazid.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or isocarboxazid.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or levoprotiline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or lofepramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or maprotiline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or medifoxamine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or metapramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or melitracen.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or mainserin.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or milnacipran.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or moclobemide.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or minaprine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or mirtzapine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or nefazodone.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or nialamide.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or nomifensine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or nortriptyline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or opipramol.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or oxaflozane.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or oxaprotiline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or oxitriptan.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or ‐hydroxytryptophan.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or paroxetine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or phenelzine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or pirlindole.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or propizepine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or protriptyline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or quinupramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or rolipram.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or rubidium.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or sertraline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or setiptiline.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or sibutramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or teniloxazine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or tianeptine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or tofenacin.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or toloxatone.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or tranylcypromine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or trazadone.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or tripramine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or tryptophan.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or venlafaxine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or viloxazine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or viqualine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf. or zimeldine.ti,ab,hw,tn,mf.]

1.5 MEDLINE (January 1966 to Oct 2000) was searched using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's search strategy for trials relating to those with schizophrenia (see Group Module) combined with the phrase:

[and exp antidepressive agents/ or exp antidepressive agents, tricyclic/ or exp amitriptyline/ or exp fluoxetine/ or exp imipramine/ or exp antidepressive agents, second‐generation/ or exp serotonin antagonists/ or exp guanosine/ or exp or nortriptyline/ or exp serotonin uptake inhibitors/ or exp paroxetine/ or amesergide/ or amineptine/ or amoxapine/ or benactyzine/ or brofaromine/ or bupropion/ or butriptyline/ or cianopramine/ or citalopram/ or clomipramine/ or clorgyline/ or clovoxamine/ or demexiptiline/ or desipramine/ or dibenzepin/ or dimetacrine/ or dothiepin/ or doxepin/ or etoperidone/ or femoxetine/ or fezolamine/ or fluvoxamine/ or ifoxetine/ or iprinodole/ or iproniazid/ or isocarboxazid/ or levoprotiline/ or lofepramine/ or maprotiline/ or medifoxamine/ or melitracen/ or metapramine/ or milnacipran/ or minapri/ or mirtzapine/ or moclobemide/ or nefazodone/ or nialamide/ or nomifensine/ or nortriptyline/ or opipramol/ or oxaflozane/ or oxaprotiline/ or hydroxytryptophan/ or phenelzine/ or pirlindole/ or propizepine/ or protriptyline/ or quinupramine/ or rolipram/ or rubidium/ or sertraline/ or setiptiline/ or sibutramine/ or teniloxazine/ or tianepine/ or tofenacin/ or tranylcypromine/ or trazodone/ or tripramine/ or tryptophan/ or venlafaxine/ or viloxazine/ or viqualine/ or zimeldine/]

(During peer review it was brought to our attention that there were some incorrectly spelt names in the lists above. We have left these as a record of the search that was undertaken. We used the catch all phrase 'antidepressant*' in the belief that this would prevent us from missing any studies. However, in the update of the review we will correct these errors)

1. 6 Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (28 Janurary 2013)

[(*antidepress* or *triptylin* or *ameser* or *amineptin* or *amoxapin* or *benactyzin* or *brofaro* or *bupropion* or *caroxa* or *pramin* or *citalopra* or *clorgy* or *oxamine*) in title, abstract and index terms of REFERENCE) or (*antidepress* or *triptylin* or *ameser* or *amoxapin* or *ipramin* or *oxetin* or *azadon* or *amineptin* or *bupropion* or *benactyzin* or *caroxa* or *citalopram* or *clorgy* or *doxepin* or *flupent* or *fluvoxamin* or *gamfexin* or *iproniazid* or *isocarboxazid* or *maprotilin* or *mians* or *minaprin* or *mirtzapin* or *moclobemid* or *nialamid* or *nomifensin* or *pramin* or *rubidium* or *sertralin* or *tranycypromin* or *tryptophan* or *viloxazin*) in interventions of STUDY)].

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches of relevant journals and conference proceedings (see Group Module). Incoming trials are assigned to relevant existing or new review titles.

2. Citation searching

The citation lists from all identified studies were inspected for additional studies.

3. Personal contact

The first author of each included study published during the last ten years was contacted for additional references and for any unpublished trials.

4. Pharmaceutical companies

Companies involved in the production of the principal antidepressant drugs were contacted and requests for additional studies made.

5. Citations

All selected studies were sought as citations on the ISI database in order to identify more trials.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of trials The reviewers independently assessed every report identified by the electronic search for relevance to this review. In cases of disagreement, the article was obtained. Every article was then independently scrutinised by the reviewers and assessed for entry into the review. Again, in cases of disagreement this was, where possible, resolved by discussion, but if doubt remained the article was added to those awaiting assessment.

2. Assessment of methodological quality The two reviewers (CW, SM) independently assigned each selected trial to quality categories described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Clarke 2002). Only trials assigned to categories A and B were selected and those assigned to category C were excluded.

3. Data management Two reviewers independently extracted data and resolved any disagreement by discussion (CW, SM, AC and GL).

4. Analysis 4.1 Intention to treat analysis Where possible the reviewers undertook an intention‐to‐treat analysis with dichotomous data. The assumption was made that those who dropped out had a poor outcome. For continuous outcomes we used the data presented in the papers. If the results for continuous outcomes did not include all randomised individuals this was stated in the table of included studies.

4.2 Data types: Outcomes are assessed using both continuous (for example means on the Hamilton Depression rating scale; HAM‐D) and dichotomous variables (for example, reduction of more than 33% in HAM‐D). We used the dichotomous data provided by authors. For dichotomous outcomes, we used the risk difference as our main summary measure.

A wide range of rating scales is available to measure continuous outcomes in mental health trials. It was therefore decided, as a minimum standard, not to include any data from a rating scale that had not been described in a peer‐reviewed journal.

Continuous data on outcomes in trials relevant to mental health issues are often not normally distributed. We only used data in which (i) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; and (ii) the standard deviation (SD), was less than half the mean (Altman 1996). Although in our protocol, we stated we would only use data which met criterion (ii) in the analysis, given the scarcity of results, we decided to include that data which did not, but have indicated this in the results section.

For continuous mean change data (endpoint minus baseline) in the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if change data are skewed. The RevMan meta‐analyses of continuous data are based on the assumption that the data are, at least to a reasonable degree, normally distributed or that the analyses within RevMan could cope with the unknown degree of skew. Without individual trial data it is not possible to formally check this assumption.

5. General In all cases data were entered into RevMan in such a way that the area to the left of the 'line of no effect' indicates a 'favourable' outcome for the antidepressant.

6. Assessing the presence of publication bias At this time there is insufficient data within the review to be able to rely upon using funnel plots or other methods to test for publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

1. Excluded studies Our search method identified several hundred studies. The majority of these were rejected, as they did not meet the primary criteria. Also many studies (especially from the 1960's and 1970's) were rejected as they used the antidepressant drug for the treatment of the schizophrenia psychosis rather than for treating depression in people with schizophrenia. These studies were not included in the list of excluded studies.

Thirty‐three studies were considered in detail and listed in the relevant table. Five were excluded, as they did not randomise the participants. Thirteen studies were excluded because the participants were not classified as depressed and one study included people without schizophrenia. Four studies did not use a placebo in the control group and nine did not use an antidepressant drug as defined. Finally, one study was excluded on the grounds that the outcome was prevention of relapse rather than treatment of the depressive syndrome itself.

2. Included studies

2.1 Participants Recruitment occurred from both outpatient and in‐patient settings. A number of the trials were quite old, and therefore the idea that the setting may help the applicability of results may be problematic. No study allocated more than 30 people to any one treatment.

Most studies employed the DMS‐III, DSM‐III‐R or RDC definitions of schizophrenia. Johnson 1981, however, used a definition of "positive Feighner or Schneiderian symptoms" that presumably corresponded to the diagnostic practices of that time in the UK. Kurland 1981 did not specify any diagnostic criteria while Prusoff 1979 used DSM‐II and the New Haven Schizophrenia Index. These latter two studies might have been using the much broader definitions of schizophrenia that were current in the USA before the widespread adoption of DSM‐III. It is likely that many of these people would therefore be regarded as having affective disorders within modern classifications.

Eight studies used specified criteria for the diagnosis of depression. Six studies used the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM‐D; Hamilton 1960). This is a widely used rating scale that provides guidance on making ratings, but does not provide any structure for the administration of questions. A higher score indicates more depressive symptoms. Of these, three studies used a depression score of 17 or more, a common criterion used in antidepressant trials (Kramer 1989; Dufresne 1988; Kurland 1981); one study a score greater than 12 (Siris 1987); one study a score greater than 15 (Johnson 1981) and one study only specified a score of greater than two on the depression or anergia scale of the HAM‐D (Becker 1983). Becker 1983 comments that 30 of the participants only scored on the anergia section of the HAM‐D and not on the depression section. Two studies used the Raskin scale with a score greater than seven being required (Hogarty 1995; Prusoff 1979). The Research Diagnostic Criteria (Feighner 1972) was used by two studies (Kramer 1989; Hogarty 1995), and the final study simply stated that the participants were depressed (Singh 1978).

Only three studies described the participants as being in the post‐psychotic phase of illness (Hogarty 1995; Siris 1987; Mulholland 1997). The three studies of chronically ill people described participants as being mixed new and chronic (Becker 1983), ambulatory (Prusoff 1979), and one said they were in remission (Johnson 1981). One study was with actively psychotic patients though the participants had received at least eight weeks of treatment (Kramer 1989) and three studies did not mention the phase of illness (Dufresne 1988; Kurland 1981; Singh 1978) but we have classified Singh 1978 as stable as the participants were described as "chronic" and had been hospitalised for at least three months.

2.2 Interventions

The mean duration of washout or drug free period was two weeks although four studies did not mention a drug free period before randomisation. Two studies did not permit the use of oral anti‐parkinsonian drugs (Kurland 1981; Prusoff 1979). Benztropine mesylate was identified in five studies whilst the sixth study did not identify which drug was used to treat extra pyramidal symptoms.

The following neuroleptics were used in the studies: chlorpromazine (Becker 1983; Kurland 1981); thiothixene (Becker 1983; Dufresne 1988); fluphenazine (Hogarty 1995; Johnson 1981; Siris 1987); haloperidol (Kramer 1989; Kurland 1981); perphenazine (Prusoff 1979); and one study used several phenothiazides (Singh 1978). Two studies used two different neuroleptics (Becker 1983; Kurland 1981). The following tricyclic antidepressants were used: imipramine (Becker 1983; Siris 1987); desipramine (Hogarty 1995; Kramer 1989); nortriptyline (Johnson 1981); amitriptyline (Kramer 1989; Prusoff 1979; Jasovic 1996). One study used two antidepressants (Kramer 1989). Viloxazine (Kurland 1981) and trazodone (Singh 1978) were used in two studies and bupropion was used by Dufresne 1988. Jasovic 1996 also used moclobemide and mianserin in two of the four randomised groups. Mulholland used sertraline.

In Becker 1983, the neuroleptic medication differed between the two randomised groups. Imipramine and chlorpromazine was therefore compared with thiothixene and placebo. In all the other studies the neuroleptic medication was the same in the two randomised groups.

2.3 Outcomes Often symptom scales were used in assessing treatment effects. These scales score the presence of specific symptoms of depression and having more symptoms indicates a greater degree of depression is present.

2.3.1 The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS: Overall 1962) BPRS changes in mental state were monitored by all of the trials except two (Johnson 1981; Siris 1987). The studies gave no further details concerning the use of the BPRS.

2.3.2 The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (Guy 1976) A rating instrument commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement during therapy. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery.

2.3.3 Hamilton Depression Inventory (HAM‐D) (Hamilton 1960) The HAM‐D is a well‐established 17‐item scale for the measurement of depression and is sensitive to change. All of the studies except one (Hogarty 1995) used this scale.

The Zung Self Rating Depression Scale (Zung 1993), used in Kurland 1981, the Raskin Depression Scale (Raskin 1970), used in Prusoff 1979 and the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961), used in Hogarty 1995, all had to be excluded as adequate data were not reported.

Uncommon outcomes such as suicide or other deaths were not reported by any of the trials. Data on adverse effects was impossible to extract because of variability in reporting. None of the trials included quality of life measures or an economic analysis.

Ten of the eleven identified studies fall into the short‐term category, lasting 12 weeks or less. One (Prusoff 1979) was classed as long term lasting 24 weeks.

3. Awaiting assessment

There are now 71 new studies waiting to be assessed from the 2013 search.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation No trial gave details about the concealment of the allocation, though three mentioned the use of computer‐ generated numbers. All of the studies had an even (or even + 1) number of people allocated to each group. This suggests the use of randomisation blocks.

2. Blinding All studies reported using double‐blind techniques, but the only details given were where two studies described using matching capsules (Becker 1983) or matching tablets (Kurland 1981).

3. Loss to follow up Three trials (Hogarty 1995; Johnson 1981; Singh 1978) did not report number of people leaving early. We assumed that there were zero dropouts from those trials. There was a particularly high dropout rate for Dufresne 1988 and Prusoff 1979. The reasons for leaving the studies early were not made explicit.

4. Data reporting A number of trials did not provide data on standard deviations and none provided confidence intervals for their estimates. No trials gave a priori power calculations or specified primary outcome measures. Many of the trials did not use an intention to treat strategy for the analysis. The quality of reporting was very variable, and only one of the trials has been published in a peer‐reviewed journal in the last 10 years (Hogarty 1995).

Effects of interventions

1. The search Thousands of citations were identified using the electronic searches. Thirty‐three had to be excluded after inspection of hard copy and are described in the excluded studies table. Only eleven studies provided data that allowed inclusion.

2. General comments 2.1 Assumptions Any assumptions made are stated elsewhere in the text. The main assumption was that the three trials that did not mention dropouts had zero dropouts (Hogarty 1995, Johnson 1981, Singh 1978). We further assumed that Kramer 1989 had equal groups of 22 each.

2.2 Overall quality Our overall judgement of the literature, taken as a whole, was that the quality was very variable and included a number of trials that did not meet current expectations concerning the reporting of randomised controlled trials. We were also struck by the limited amount of evidence that was available. Given the variable quality of the trials and the different methods of reporting the results, the possibility of providing a quantitative synthesis is limited.

3. COMPARISON: ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC

3.1 No important clinical response This was defined in some studies as no response in global psychiatric status, as measured by CGI, or as no significant reduction in the commonly used HAM‐D scale. Such categorical data were reported by only five studies (Hogarty 1995; Johnson 1981; Mulholland 1997; Prusoff 1979; Singh 1978). There was a significant benefit to the use of antidepressants in the meta‐analysis of these five trials (n=209, 5 RCTs, summary risk difference fixed effects ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.13, NNT 4 95% CI 3 to 8). These data were statistically homogeneous. When a random effects model was used, the results were similar (RD ‐0.27 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.12). Only Johnson 1981 gave a criterion for recovery in terms of a reduction in HAM‐D scores. All the other studies mentioned improvement on the Clinical Global Impression scale. We could not investigate publication bias using a funnel plot because of the small number of studies included in the review.

3.2 Mental state 3.2.1 Depressive symptoms Six trials reported the outcome for depression assessed by the Hamilton Rating Scale (HAM‐D) score at the end of the trial. Overall there seemed to be a statistically significant difference between antidepressant and placebo and benefit to using antidepressants in people with schizophrenia who are depressed. This was only apparent, however, when a fixed effects model was used (n=261, 6 RCTs, WMD fixed effects ‐2.2 95% CI ‐3.8 to ‐0.6; WMD random effects ‐2.1 95% CI ‐5.04 to 0.84). For three of the studies (Dufresne 1988; Singh 1978; Siris 1987) the standard deviation was more than half the mean for at least one of the groups, indicating a severe degree of skew in the data. When the results from the trials with skewed data were separated, the remaining three trials did not find a significant benefit to the use of antidepressants, even with a fixed effects model, though of course the statistical power was reduced. In addition, there was a significant degree of heterogeneity in the results of the three trials with skewed data. In particular, the trial by Singh 1978 appeared to have an important influence in determining a positive result for this group of trials. Singh 1978 was the oldest of the trials included in the review. Finally, the continuous data used was also calculated without including all people randomised, in other words it is not clear whether the authors used an intention to treat strategy in the analysis. Of the six studies, only Mulholland 1997, and possibly Singh 1978, used an intention to treat strategy.

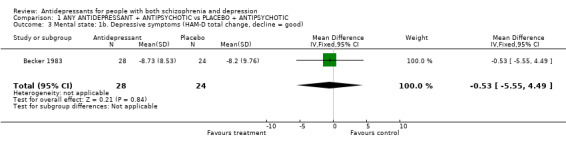

Becker 1983 measured change using the Hamilton Scale (endpoint ‐ baseline) but no differences were apparent (n=52, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.53 CI ‐5.6 to 4.5).

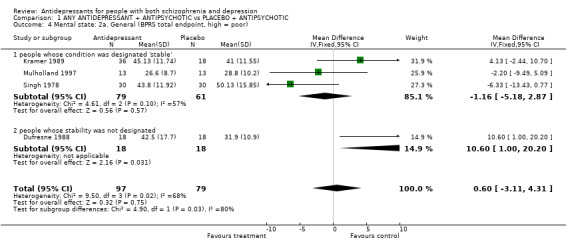

3.2.2 Psychotic symptoms Some clinicians are concerned that antidepressants can lead to worsening of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia (Kramer 1989). We also reported from four trials on the BPRS scores at the trial endpoint. Three of these trials were studying schizophrenia during a relatively stable phase of the illness and Dufresne 1988 did not provide information about the phase of illness. The three studies including people at the relatively stable phase of their illness found no differences between groups (n=140, 3 RCT, WMD ‐1.2 CI ‐5.2 to 2.3, heterogeneous Chi square 4.6, df 2, p=0.1). Dufresne 1988 found a statistically significant difference favouring the placebo (n=36, 1 RCT, MD 10.6 CI 1.0 to 20).

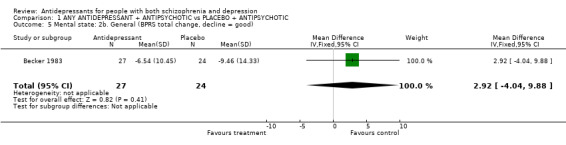

Again Becker 1983 measured change (endpoint ‐ baseline) rather than end point state. Using the BPRS the study found no difference between groups (n=51, 1 RCT, MD 2.9 CI ‐4.0 to 10).

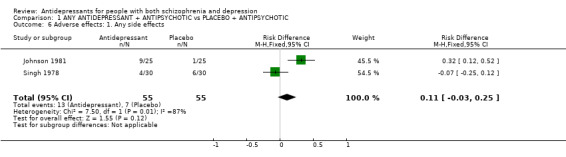

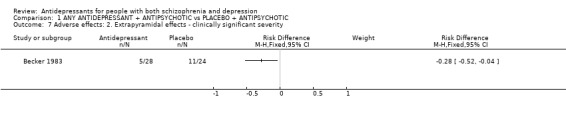

3.2.3 Adverse effects Two studies reported on the outcome of 'any side effects'. Heterogeneous data are equivocal (n=110, 2 RCT, RD fixed 0.11 CI ‐0.03 to 0.25, Chi square 7.5, df=1, p=0.0062). In Becker 1983 extrapyramidal adverse effects were reported less often by those allocated to antidepressant (n=52, 1 RCT, RD fixed ‐0.28 CI ‐0.5 to ‐0.04).

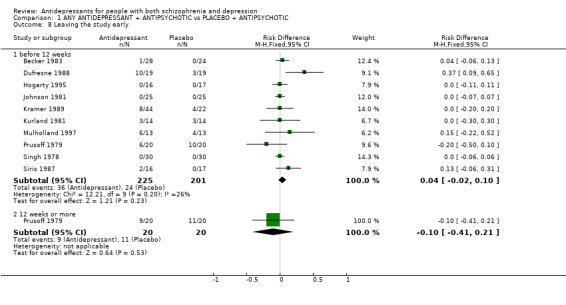

3.2.4 Leaving the study early Only about 10% of people left these studies by 12 weeks. There was no difference apparent between those allocated placebo and those given an antidepressant (n=426, 10 RCT, RD fixed 0.04 CI ‐0.02 to 0.1). In some studies, the authors did not report any dropouts and we have assumed there were no dropouts in those studies as mentioned in the table of included studies.

Discussion

1. Limited, poor data The literature, taken as a whole contained a number of deficiencies. Many of the studies were of poor quality from the perspective of current practice in randomised trials or did not meet the more recent criteria for reporting summarised in the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001).

1.1 Diagnoses Some of the studies are now over two decades old, and may well have used diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia that do not correspond to those that have subsequently been internationally agreed. A particular danger is that these trials included people who would now receive the diagnosis of affective disorder. The diagnosis of depression can be difficult to make in people with schizophrenia. Most of the trials mentioned that they were alert to the possibility that extrapyramidal symptoms and negative symptoms of schizophrenia could mimic some aspects of the depressive syndrome. Most of the studies used the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression to determine entry into the trial. This scale has the advantage of relying upon the clinical judgement of the clinician to decide upon the presence of symptoms. On the other hand, it is poorly standardised. A measure such as the Beck Depression Inventory, which was also used by some investigators, is a good method of determining depression in people with schizophrenia. It concentrates on some of the cognitive aspects of depression, which are therefore less likely to be confused with the extra‐pyramidal symptoms and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It is likely that the participants were heterogeneous, which supports the view that a random effects model is a more reliable method of producing a summary estimate.

1.2 Interventions We chose to analyse the data for any antidepressant. It is possible, of course, that antidepressants with differing pharmacological profiles could have different effectiveness in depression in people with schizophrenia. In fact there is little evidence for different efficacy from trials of people with depression alone (Freemantle 2000). Despite this, if there were sufficient data it would be wise to check for differences in efficacy according to the pharmacological action of the antidepressant.

1.3 Quality of methods and reporting All the studies were small and gave few methodological details concerning the concealment of randomisation. A number of the trials were poorly reported and gave little or no statistical information. The results were reported in a variety of ways and none gave an indication that a primary outcome had been decided before the trial began. This raises the possibility the analyses performed within the trials were selectively reported. It is unusual for so few trials (5 of 11) to have given results in terms of dichotomous outcomes. The other main quantitative analysis we were able to perform used the HAM‐D as a continuous measure of outcome, but this was available in only 6 of the 11 studies. In 3 of these studies, the data appeared skewed and though one would normally expect this to increase the variance estimates, it again encourages caution in relation to the findings. There were a number of studies where the continuous outcomes may not have included all randomised subjects. This will tend to have exaggerated the treatment effect.

1.4 Publication bias There is also a distinct possibility of publication bias, though we were unable to investigate this adequately.

2. Applicability of results The main limitation on applying these findings to current practice may be that some of the earlier studies were not using current diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. In particular, the studies of Kurland 1981 and Prusoff 1979. The study of Singh 1978 used the research diagnostic criteria. One possibility is that some of the participants in these trials had affective disorders according to modern diagnostic criteria. The response to antidepressants may therefore have been overestimated.

It was difficult to be sure, for many studies, whether participants were in a stable post‐psychotic phase of illness or whether they were still in the acute phase. We have attempted to classify the studies on the basis of the information given. For example, we have classified Kramer 1989 as stable. This was because the participants had been treated for five weeks with anti‐psychotics and had shown a drop in their BPRS scores in the paper.

3. COMPARISON: ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC

3.1 Clinical response There was a significant benefit for those allocated antidepressants (NNT 4 CI 3 to 8). However, it is important to be cautious when drawing conclusions from these data. This effect is, if anything, larger than the NNT of 7 for fluoxetine in depression (in the absence of schizophrenia) suggested by the meta‐analysis of Bech 2000. The studies included in this outcome used a variety of different treatments and participants were recruited from several sources.

The evidence in this review does indicate some benefit to using antidepressants in treating depression in people with schizophrenia. The current evidence, though, is poor and a fairer conclusion is probably that the use of antidepressants is unproven. Some authors have suggested that some of the newer atypical antipsychotic drugs could be better than the more traditional antipsychotics in treating depression in people with schizophrenia (Tollefson 1998). This claim deserves further investigation. Nevertheless, depression is commonly found in people with schizophrenia and there will remain circumstances when clinicians will wish to treat depressive syndromes with antidepressants. The current empirical justification for this strategy is poor. Larger multicentre trials are needed if we wish to be more confident that antidepressants are effective for this clinical indication.

Some commentators have argued that antidepressants should not be used in the acute phase of illness and only during more stable periods. The trials did not provide clear guidance. Most of these trials, however, investigated schizophrenia after the resolution of the acute episode. Patients were often recruited from outpatient departments, or a few weeks after admission. We have much less information about whether the patients in the trials also had evidence of active psychotic phenomena in addition to any depressive symptoms, but it is likely that the participants, though stable, had psychotic symptoms in addition to any depressive symptomatology.

3.2 Heterogeneity Given the heterogeneity of participants and interventions, it is unsurprising that the studies included in the continuous outcome analysis found differences in effect size. When we used a statistical model (random effects) that allowed for these differences, there was no longer any significant benefit to using antidepressant medication for depressive symptoms or general improvement. We regard the random effects model as a more conservative approach towards analysing these data and put most emphasis on this analysis. The random effects model assumes that there are different effect sizes in the different studies, and so the model estimates the distribution of effect sizes from which the individual studies have been drawn. It seems reasonable therefore to conclude that there is currently little statistical evidence to support the effectiveness of antidepressants for this clinical indication.

3.3 Adverse effects and leaving the study early There was little extractable data on adverse effects. No consistent pattern emerged. More data were available on leaving the study early. This could be interpreted as a measure of the acceptability of the adjunctive treatment with antidepressants. There was not sufficient statistical evidence to suggest any difference in the number leaving the study early. This result supports the earlier conclusion that there is no evidence for any harmful effects of using antidepressants in people with schizophrenia and depression.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For clinicians The evidence summarised in this review is not sufficiently robust to provide clear guidance about the use of antidepressants to treat depression in schizophrenia. Neither does it refute the use of antidepressants for those whose psychotic schizophrenic illness is complicated by clear depressive syndrome. On balance it supports the use of antidepressants for this indication but the treatment effect calculated by the meta‐analysis is probably an overestimate and the statistical results only suggest benefit in some of the analyses. There was no evidence to support a harmful effect of antidepressants once the acute phase of illness was over.

2. For people with schizophrenia People with schizophrenia with additional symptoms of depression can be reassured that there are no data to refute the use, and some to support adding antidepressants to standard antipsychotic regimens. It would be entirely understandable, however, if people offered adjunctive medication were only to accept it within the context of a well‐designed randomised trial.

3. For policy makers Currently there is no good information to guide policy makers.

4. Note: the 71 new citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.

Implications for research.

1. General Even with these few studies, data were lost because of poor reporting. We would all be better informed if all data were either reported in usable form or were at least accessible from authors or a central repository.

2. Specific At present there is no convincing evidence to support the use of antidepressants in the treatment of depression in people with schizophrenia. Depression in schizophrenia is an important and common clinical problem. Determining the optimal pharmacological method of treating depression in this group will require further research. Further research is needed in order to guide clinicians in their management and use of antidepressant medication. This review, if nothing else, should help guide researchers to design a study of adequate power (at least 150 per group) and the use of clinically meaningful outcomes.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 January 2013 | Amended | Update search of Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trial Register (see Search methods for identification of studies), 71 studies added to awaiting classification. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 October 2008 | Amended | Author correction |

| 23 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 6 February 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

This review was made possible thanks to the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit of the Welsh Office. The reviewers would also like to thank Clive Adams and Leanne Roberts for all their help and advice during the production of this review. We also acknowledge the help and advice of Hollie Thomas. Letters were sent to all of the main authors and we are grateful to those who responded: Professor E. Hogarty, Dr R Dufresne, Professor M Jasovic Gasic and Ciaran Mulholland.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No important clinical response (Global Psychiatric Status, CGI, or significant reduction in HAM‐D) | 5 | 209 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.26 [‐0.39, ‐0.13] |

| 2 Mental state: 1a. Depressive symptoms (HAM‐D total endpoint, high = poor) | 6 | 261 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.16 [‐3.77, ‐0.55] |

| 2.1 non‐skewed data | 3 | 132 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.18 [‐3.06, 0.70] |

| 2.2 skewed data | 3 | 129 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.86 [‐7.98, ‐1.73] |

| 3 Mental state: 1b. Depressive symptoms (HAM‐D total change, decline = good) | 1 | 52 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.53 [‐5.55, 4.49] |

| 4 Mental state: 2a. General (BPRS total endpoint, high = poor) | 4 | 176 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [‐3.11, 4.31] |

| 4.1 people whose condition was designated 'stable' | 3 | 140 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.16 [‐5.18, 2.87] |

| 4.2 people whose stability was not designated | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.60 [1.00, 20.20] |

| 5 Mental state: 2b. General (BPRS total change, decline = good) | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.92 [‐4.04, 9.88] |

| 6 Adverse effects: 1. Any side effects | 2 | 110 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.03, 0.25] |

| 7 Adverse effects: 2. Extrapyramidal effects ‐ clinically significant severity | 1 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8 Leaving the study early | 10 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 before 12 weeks | 10 | 426 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.02, 0.10] |

| 8.2 12 weeks or more | 1 | 40 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.41, 0.21] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 1 No important clinical response (Global Psychiatric Status, CGI, or significant reduction in HAM‐D).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 2 Mental state: 1a. Depressive symptoms (HAM‐D total endpoint, high = poor).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 3 Mental state: 1b. Depressive symptoms (HAM‐D total change, decline = good).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 4 Mental state: 2a. General (BPRS total endpoint, high = poor).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 5 Mental state: 2b. General (BPRS total change, decline = good).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 6 Adverse effects: 1. Any side effects.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 7 Adverse effects: 2. Extrapyramidal effects ‐ clinically significant severity.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ANY ANTIDEPRESSANT + ANTIPSYCHOTIC vs PLACEBO + ANTIPSYCHOTIC, Outcome 8 Leaving the study early.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Becker 1983.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, computer generated code. Blindness: double, matched capsules. Duration: 4 weeks (preceded by 2 weeks medication free). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM II & RDC), with depression (RDC Major depressive syndrome & HAM‐D 3/4 (depressed) or 3/4 on work & activities items (anergic)). N=52. Sex: female 17 male 35. Age: mean 38 years. History: both chronic & newly admitted. Setting: hospital. Phase: no information. Medication history: no information. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine + imipramine: mean dose 156 mg/day. N=28. 2. Thiothixene + placebo. N=24. Both groups: benztropine and diphenhydramine for sleep. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: BPRS, HAM‐D.

Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ General: CGI (no results by group). Side effects: no results by group. |

|

| Notes | There were different antipsychotics in the two groups. 30 people anergic not depressed on HAM‐D. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Dufresne 1988.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double, no further details. Duration: 10 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM III) with depression (DSM III major depressive episode for preceding 2 weeks, prominent dysphoric mood & HAM‐D >18). N=38. Sex: female 14, male 24. Age: mean 41 years. History: mean duration of current exacerbation 18 weeks, stabilised on thiothixene. Setting: hospital. Phase: no information. Medication history: no information. | |

| Interventions | 1. Thiothixene + bupropion: dose mean 446 mg/day SD 413. N=19. 2. Thiothixene + placebo. N=19. Both groups thiothixene: dose mean 22 mg/day (SD 16). | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: BPRS, HAM‐D (4 weeks).

Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ General: CGI (no means). Mental state: BPRS, HAM‐D (10 weeks, >50 loss to follow up). Side effects: AIMS, REPS (no means). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hogarty 1995.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: "double". Duration: 12 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (RDC), depression (Raskin Depression >7 (persistent distress for 3 weeks)). N=33. Sex: female 12, male 21. Age: mean ˜ 32 years. History: chronic patients. Setting: outpatients. Phase: chronic distress or defect state for at least 3 months. Medication history: early phases of study optimised use of neuroleptics and anticholinergics. | |

| Interventions | 1: Desipramine: dose 50mg/day increased to 150 mg. N=16. 2: Placebo. N=17. Both groups: : fluphenazine decanoate, benztropine mesylate. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical Improvement: (CGI "much improved") Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS , BDI, Covi anxiety scale, Taylor anxiety scale. No SDs given |

|

| Notes | Assumed zero dropouts. ITT analysis found statistically significant benefit for antidepressant on BDI (P=0.04) and BPRS (P=0.03). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jasovic 1996.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double, no further details. Duration: 4 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐IV), depression (HAM(D) >=16). N=52. Sex: no information. Age: no information. History: no information. Phase: no information. Setting: no information. Medication history: no information. | |

| Interventions | 1. Amitryptilline. N=12. 2. Mianserin N=11. 3. Moclobeminde. N=14. 4. Placebo. N=15. Both groups: unspecified neuroleptic medication. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: HAM(D) Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no means or SDs). |

|

| Notes | Abstract only. All antidepressant groups (1,2,& 3) combined in results. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Johnson 1981.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double, identical placebo tablets. Duration: 5 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (positive Feighner or Schneiderian symptoms), depression (lowered mood state, BDI or HAM‐D >15). N= 50. Sex: female 27, male 23. Age: mean ˜ 31 years. History: clinically depressed for 1 week, two or more previous admissions for schizophrenia. Setting: hospital. Phase: those with active schizophrenic symptoms excluded. Medication history: "free from extrapyramidal signs". | |

| Interventions | 1. Nortriptyline: dose 75‐150 mg/day. N=25. 2. Placebo. N=25. Both groups: fluphenazine decanoate or flupenthixol decanoate, oral anti‐parkinsonian drugs and benzodiazepines. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: HAM‐D.

Clinical recovery (HAM‐D reduction 33%).

SIde effects. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS (no results). |

|

| Notes | Assumed zero dropouts. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kramer 1989.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double, no further details. Duration: 4 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐III, BPRS >30), depression (RDC major depressive episode. HAM‐D >17). N=58. Age: mean ˜ 37 years. History: chronically psychotic, ˜ 15 years since diagnosis. Setting: hospital. Phase: 5 weeks after acute psychosis onset. Medication history: medication free for 2 weeks then 5 weeks haloperidol and benztropine optimised to minimise EPS. | |

| Interventions | 1. Desimipramine hydrochloride: dose 3.5 mg/kg/day. N=22. 2. Amitryptilline: dose 3.5mg/Kg/day. N=22. 3. Placebo. N=22. Both groups: haloperidol 0.4mg/kg/day, benztropine 6 mg/day. | |

| Outcomes | Mental State: HAM‐D & BPRS. Leaving the study early. | |

| Notes | 66 randomised and assume that 22 were randomised to each group. Did not perform ITT analysis: 54 people of 66 randomised included in results. Group 1 and 2 combined in results. Checked compliance with plasma measurement. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kurland 1981.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double, identical placebo tablets. Duration: 4 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (not otherwise specified), depression (HAM‐D >18). N=28. Sex: no information. Age: range 19‐53 years. History: no information. Setting: no information. Phase: no information. Medication history: stabilised for 2 wks on antipsychotic. | |

| Interventions | 1. Haloperidol or chlorpromazine + viloxazine: dose 150‐300mg depending upon response. N=14. 2. Haloperidol or chlorpromazine + placebo. N=14. Both groups: haloperidol dose 6‐15mg/day, chlorpromazine dose 75‐300mg/day. | |

| Outcomes | Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Global improvement: CGI (no means or SDs). Mental state: BPRS, HAM(D), Zung Self Rating Depression Scale (no means or SDs). |

|

| Notes | Viloxazine v placebo comparison reported for dropouts. Assumed 7 people randomised to each group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Mulholland 1997.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, computer generated numbers. Blindness: double, identical placebo capsules. Duration: 8 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐III‐R), depression (>= 3 on BPRS depression and >= 15 on BDI). N=26. Sex: female 10, male 16. Age: mean 38 years. History: duration ill ˜ 15 years. Setting: out‐patients. Phase: stable, no admission to hospital in previous 6 months. Medication History: people with significant EPS excluded. All on neuroleptic medication. 16 of the 26 were on anticholinergics. | |

| Interventions | 1. Sertraline: dose 50 mg/day 4 weeks, 100 mg/day next 4 weeks if tolerated. N=13. 2. Placebo. N=13. Both groups: neuroleptic and anticholinergic. | |

| Outcomes | Mental State: HAM(D), BPRS.

Leaving the study early.

Clinical recovery: CGI minimal or better improvement. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BDI (HAM(D) used in preference). |

|

| Notes | ITT analysis performed. Unpublished results provided by authors. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Prusoff 1979.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised no further details. Blindness: double, identical placebo. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM II & NHSI (4/16 symptoms), depression (RDS >7). N=40. Sex: "about half male". Age: range 18‐65 years. History: no details. Setting: out‐patients. Phase: were treated with perphenazine for a month before randomisation. Medication history: perphenazine optimised to minise psychotic symptoms. | |

| Interventions | 1. Amitriptyline hydrochloride: dose 100‐200mg/day. N=20. 2. Placebo. N=20. Both groups: perphenazine. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical recovery: global psychiatric status moderate improvement.

Leaving the study early. Unable to use ‐ Mental state: BPRS, HAM(D), RDS (no SDs). Quality of life: SCL‐90 (no SDs). Social functioning: Social Adjustment Scale (no SDs). |

|

| Notes | High dropout rate of over 50% at 6 months. Did not perform ITT analysis, report on 24 of 40 people at 4 months. Results found statistically significant improvement for antidepressant group at 4 months for Raskin depression scale and HAM(D) anxiety‐depression subscale. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Singh 1978.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double. Duration: 6 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM III & RDC), depression (RDC, HAM(D) >18). N=60. Sex: female 26, male 34. Age: mean ˜ 43 years. History: mean length of illness ˜18 years. Setting: hospital. Phase: "chronic hospitalised schizophrenic patients". Medication history: 5 week stabilisation on phenothiazine, and anticholinergic if prescribed. | |

| Interventions | 1. Trazodone: dose 150‐300mg/day. N=30. 2. Placebo. N=30. Both groups: phenothiazine and anticholinergic. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: HAM(D), BPRS.

Clinical Recovery: CGI "improved".

Side effects. Unable to use ‐ Behaviour: Nurse Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (no SDs). |

|

| Notes | Assumed no drop outs. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Siris 1987.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, no further details. Blindness: double. Duration: 6 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizoaffective (RDC), depression (RDC 4 weeks, HAM(D) >12). N=33. Sex: female 17, male 16. Age: mean ˜ 31 years. History: no information. Setting: 28 out‐patients 5 in‐patients. Phase: non‐psychotic or residually psychotic. Medication history: depression not responsive to 1 wk of benztropine 6mg/day. | |

| Interventions | 1. Imipramine: dose 200mg/day. N=17 2. Placebo. N=16 Both groups: fluphenazine decanoate, benztropine mesylate unchanged. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: HAM(D) (extracted from SADS). Unable to use ‐ Global impression: Global Assessment Scale (no SDs). Mental state: other items of SADS (not comparable with BPRS results). |

|

| Notes | Non‐ITT analysis. 2 drop outs from placebo group. Also checked compliance with plasma measurement. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Assessments: HAM‐D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory RDS: Raskin Depression Scale CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale SCL‐90 Symptom checklist

Diagnostic criteria RDC: Research Diagnostic Criteria DSM‐II Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 2nd edition DSM‐III Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 3rd edition DSM‐III‐R Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 3rd edition revised. NHSI: New Haven Schizophrenia Index

Statistical abbreviations: SD standard deviation ITT Intention to treat analysis

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Arango 2000 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Arato 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Benkert 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: with schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no placebo. |

| Duval 1997 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: with schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Eikmeier 1991 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Goff 1990 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Goff 1995 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Goode 1983 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Hiemke 1994 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Joffe 1998 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Kirli 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no placebo group. |

| Knights 1979 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Koreen 1993 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Krakowski 1997 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Lee 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Lee 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no placebo group. |

| Muller 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no placebo group. |

| Salokangas 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Silver 1992 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Silver 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Siris 1982 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Siris 1986 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Siris 1987a | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Siris 1989 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Siris 1990 | Participants: randomised. Intervention: not depressed. |

| Siris 1993 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression, but also with substance abuse. |

| Siris 1994 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: imipramine and placebo. Outcome: study of antidepressant maintenance. |

| Spina 1994 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

| Thakore 1996 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Tollefson 1996 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Tollefson 1998 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Tollefson 1999 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: schizophrenia and depression. Intervention: no antidepressant. |

| Waehrens 1980 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: not depressed. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Addington 2002.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Addington 2002a.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Berk 2002.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Blumberger 2011.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Chen 2007.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Dawes 2012.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Eli 2006.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Fitzgerald 2004.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Friedman 2005.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Geddes 2010.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Gerson 1970.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Gunby 1966.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Han 2006.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Hu 2004.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Huang 2003.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

ISRCTN42305247 2010.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Izakova 2007.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Izakova 2009.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Jasovic‐Gasic 1990.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Jasovic‐Gasic 1991.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Jin 2002.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Kasckow 2001.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Kasckow 2010a.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Kim 2006.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Krumholz 1968.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Lehmann 1970.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Liu 2002.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Liu 2003.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Mulholland 1997a.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Mulholland 1998.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Mulholland 2003.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Muller 1997.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

NCT00047450.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

NCT00531518.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

NCT01041274.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

NCT01724372.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Ou 2007.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Overall 1961.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Pierson 2006.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Postel 1971.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Ren 2004.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Risch 2006.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Ruan 2008.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Sheremata 2004.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Song 2003.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

St. Jean1966.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |